Abstract

We investigate conditions under which a semicomputable set is computable. In particular, we study topological pairs which have a computable type, which means that in any computable topological space, a semicomputable set S is computable if there exists a semicomputable set T such that is homeomorphic to . It is known that has a computable type if G is a topological graph and E is the set of all its endpoints. Furthermore, the same holds if G is a so-called chainable graph. We generalize the notion of a chainable graph and prove that the same result holds for a larger class of spaces.

Keywords:

computable topological space; computable type; topological graph; chainable graph; generalized graph MSC:

03D78; 03F60

1. Introduction

A compact set is semicomputable if its complement can be effectively exhausted by rational open balls. On the other hand, a compact set is computable if it is semicomputable and we can effectively enumerate all rational open balls which intersect S. By the mere definition, it is clear that each computable set is semicomputable, while there exist some examples which show that the reverse implication does not hold. For instance, there exists such that is a semicomputable set and itself is not a computable number (therefore, is not a computable set) [1]. Here, by the computable number we mean every real number that can be effectively approximated by a rational point for any given precision. Moreover, there exists a nonempty semicomputable subset of which does not contain any computable point [2]. The notions of a semicomputable and a computable set can be naturally defined in the setting of computable metric and topological spaces.

Although the implication

is not true, in general, there are certain additional assumptions on S under which (1) holds. For example, each semicomputable compact manifold is computable. Therefore, each semicomputable topological circle is computable, but also a Warsaw circle, which is not a manifold, is computable if it is semicomputable. Moreover, if S is a semicomputable circularly chainable continuum that is not chainable, then S is computable. Also, the same is true if S is a continuum chainable from a to b, where a and b are computable points (i.e., is a semicomputable set) [3,4,5].

We say that a topological space A has a computable type if for any computable topological space the following holds: if S is semicomputable in and homeomorphic to A, then S is computable in . For example, the previously mentioned result for compact manifolds now can be stated in the following way: each compact manifold has a computable type.

The fact that there exists such that is semicomputable, but not computable, means that does not have a computable type. Related to this situation, we have the following concept of computable type.

If A is a topological space and B its subspace, then we say that is a topological pair. We say that a topological pair has a computable type if for any computable topological space the following holds: if is an (topological) embedding such that and are semicomputable sets, then is a computable set.

Using this terminology, we can say that has a computable type if S is a continuum chainable from a to b. In particular, has a computable type.

Recently, Amir and Hoyrup examined conditions under which a finite polyhedron has a computable type (see [6]). They also examined the computable type and strong computable type in [7].

Some results regarding computable type and (in)computability of semicomputable sets can be found in [8,9,10].

Inspired by the notion of a topological graph, in [11] the authors have defined the notion of a chainable graph and have proven that the claims stated for topological graphs, hold for chainable graphs, as well. Namely, a topological graph is considered to be any topological space obtained as a union of finitely many arcs such that every two of them which intersect, intersect in exactly one point which is an endpoint of both of them. The definition of chainable graph arcs has been replaced by chainable continua. It is proved in [12] that has computable type if G is a graph and E is the set of all its endpoints. In [11] it was proved that the same holds for chainable graphs.

In this paper, we generalize the notion of a chainable graph from [11] and we define the notion of a generalized graph. While in a chainable graph, every two edges can intersect only in their endpoints, in the definition of a generalized graph we only demand that two edges (which are chainable continua) intersect finitely many points. More precisely, we say that a triple is a generalized graph if G is a topological space, V is a finite set and is a finite set of pairs , where are distinct points and is a Hausdorff continuum chainable from a to b, such that the following holds: A is the union of V and all such K and for all such that we have that is a finite set. We show that generalized graphs are indeed a generalization of chainable graphs. We prove that has a computable type if is a generalized graph and E is the set of all its endpoints.

It should be mentioned that Amir and Hoyrup in [7] showed that, for the purpose of studying computable type, computable topological spaces are no more general than computable metric spaces, or in fact the Hilbert cube. However, for the techniques that we use in this paper, a computable topological space is a natural ambient space.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we recall some basic notions, both from computability and topology, needed to state our main result. For background on computable analysis and some recent results we refer the reader to [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

2.1. Computable Functions

Let , . A function is said to be computable if there are computable (i.e., recursive) functions such that

for each . A function is said to be computable if there exists a computable function such that

for each , .

For a set X, let denote the family of all finite subsets of X. A function is called computable if the set

is computable and if there is a computable function such that

for each .

From now on, let , be some fixed computable function whose range is the set of all nonempty finite subsets of .

2.2. Computable Metric Space

Let be a metric space and be a sequence in X such that is dense in . A triple is said to be a computable metric space if the function , , is computable.

For example, is a computable metric space, where d is the Euclidean metric on for , and is some effective enumeration of .

If is a metric space, and , then by we denote the open ball of radius r centered at x and by we denote the corresponding closed ball. If , we will denote by the closure of A in .

Let be a fixed computable metric space. Let and , . We say that is an (open) rational ball in a computable metric space .

Let and be fixed computable functions such that the image of q is the set of all positive rational numbers and such that . For we denote

Note that is the set of all rational balls in . For let

Then, is the set of all finite (nonempty) unions of rational balls.

Now we can state the following definitions:

- a closed set in is a computably enumerable (c.e.) set in if the set is a c.e. subset of ;

- a compact set in is a semicomputable set in if the set is a c.e. subset of ;

- a compact set in is a computable set in if S is both c.e. and semicomputable in .

These definitions do not depend on the choice of the functions q, , and .

2.3. Computable Topological Space

Let be a topological space and let be a sequence in such that the set is a basis for . A triple is called a computable topological space if there exist c.e. subsets such that:

- if are such that , then ;

- if are such that , then ;

- if and are such that , then there is such that and ;

- if are such that , then there are such that , and .

If is a computable metric space, then it can be shown (see [35]) that is a computable metric space, where is the topology induced by d and is the sequence of rational open balls defined earlier.

Let be a computable topological space and, for , let .

We define semicomputable, computably enumerable and computable sets in in the same way as in the case of computable metric spaces. As before, these definitions do not depend on the choice of the sequence ).

If is a computable metric space and , then S is c.e./semicomputable/computable in if and only if S is c.e./semicomputable/computable in .

It should be mentioned that if is a computable topological space, then the topological space need not be metrizable (see Example 3.2 in [35]).

Note that is Hausdorff and second countable if is a computable topological space. So, if S is a compact set in , then S, as a subspace of , is a compact Hausdorff second countable space, which implies that S is a normal second countable space, and therefore, it is metrizable. We will use this fact later.

The proofs of the following facts, which will be used frequently in this paper, can be found in [35].

Theorem 1.

Let be a computable topological space. There exist c.e. subsets such that:

- 1.

- if are such that , then ;

- 2.

- if are such that , then ;

- 3.

- if is a finite family of nonempty compact sets in and is a finite subset of , then for each there is such that

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- if are such that , then ;

- (iii)

- if and are such that , then .

Proposition 1.

Let be a computable topological space, let be a semicomputable set in this space and let . Then, the set is semicomputable in .

We say that is a computable point in if is a c.e. subset of . The proof of the following proposition can be found in [12].

Proposition 2.

Let be a computable topological space and let . Then, the following holds:

Let us recall the notion of computable type. We say that a topological space A has a computable type if the following holds: if S is a semicomputable set in a computable topological space such that S is homeomorphic to A, then S is computable , . Furthermore, we say that a topological pair has a computable type if the following holds: if S and T are semicomputable sets in a computable topological space such that is homeomorphic to , then S is computable in .

2.4. Chainable and Circularly Chainable Hausdorff Continua

Let X be a set and be a finite sequence of subsets of X. We say that is a chain in X if the following holds:

for all . Also, we say that is a circular chain in X if the following holds:

for all .

Let and . We say that covers A if , and we say it covers A from a to b if it is also and .

Let be a metric space. A (circular) chain is said to be an -(circular) chain for some , if for each and it is said to be an open (circular) chain if every is open in . In the same way, we define the notion of a compact (circular) chain.

Let be a continuum, i.e., a connected and compact metric space. We say that is a (circularly) chainable continuum if for every there exists an open -(circular) chain in which covers X. For , we say that is a continuum chainable from a to b if for every there exists an open -chain which covers X from a to b.

The proofs of the following facts can be found in [5].

Proposition 3.

Let be a continuum and .

- 1.

- is a chainable continuum from a to b if and only if for each there is a compact ϵ-chain in which covers X from a to b.

- 2.

- is a (circularly) chainable continuum if and only if for each there is a compact ϵ-(circular) chain in which covers X.

A Hausdorff continuum is a connected and compact Hausdorff topological space.

Let and be families of sets. We say that refines if for each there exists such that .

Let X be a Hausdorff continuum. We say that X is a (circularly) chainable Hausdorff continuum if for each open cover of X there is an open (circular) chain in X which covers X such that refines . We similarly define that a Hausdorff continuum is chainable from a to b.

It follows easily that a metric space is a (circularly) chainable continuum if and only if topological space is a (circularly) chainable Hausdorff continuum (where is the topology induced by d). Also, is a continuum chainable from a to b if and only if is a Hausdorff continuum chainable from a to b. See Section 3 in [3].

Remark 1.

Let X and Y be topological spaces and let be a homeomorphism. Then is easy to see that X is a (circularly) chainable Hausdorff continuum if and only if Y is a (circularly) chainable Hausdorff continuum. Furthermore, if , then X is a Hausdorff continuum chainable from a to b if and only if Y is a Hausdorff continuum chainable from to .

2.5. Topological and Chainable Graph

Here, we recall the notions of the topological graph (see [12]) and its generalization, the chainable graph (see [11]).

Let be a nonempty finite family of (non-degenerate) line segments in , , such that for all , holds: if then , where a is an endpoint of both I and J. Any topological space G homeomorphic to is called a graph.

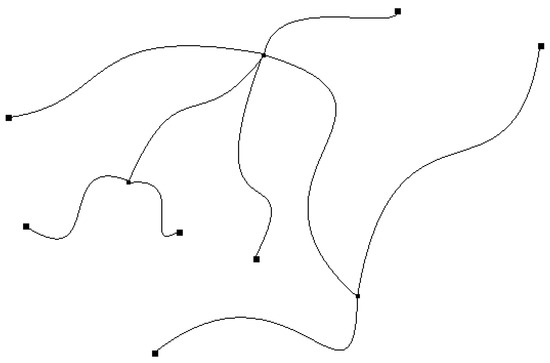

For the graph G we say that is an endpoint of G if there exists an open neighborhood N of x in G such that N is homeomorphic to by a homeomorphism which maps x to 0. If is the family from the definition of G, then x is an endpoint of G if and only if there exists a unique such that x is an endpoint of I (see [12]). See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Graph. The highlighted points are its endpoints.

The following result was proved in [12].

Theorem 2.

Let G be a graph and let E be the set of all endpoints of G. Then has computable type.

Let A be a topological space. Suppose V is a finite subset of A and let be a finite family of pairs , where , , and K is a subspace of A such that K is a Hausdorff continuum chainable from a to b and such that . Suppose

and the following holds:

- (i)

- for all , , there exists at most one K such that ;

- (ii)

- if and , then ;

- (iii)

- if and , then .

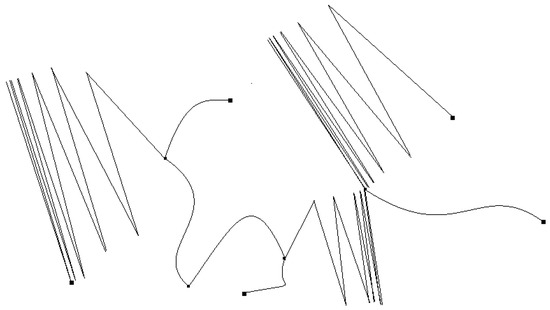

Then, we say that the triple is a chainable graph. Also, we say that is an endpoint of if there exists a unique such that for some (note that such a b also has to be unique by (ii)). See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Chainable graph. The highlighted points are its endpoints. Three of these chainable continua are homeomorphic to the continuum K from Example 1.

For example, if K is a Hausdorff continuum chainable from a to b, , then is a chainable graph and a and b are all of its endpoints.

If G is a topological graph, then it is not hard to see that there exist and V such that is a chainable graph. On the other hand, if is a chainable graph, then G need not be a graph. See [11].

The proof of the following proposition, a generalization of Theorem 2, can be found in [11].

Theorem 3.

If is a chainable graph and B is the set of all its endpoints, then has a computable type.

3. Generalized Graph

In this section, we consider spaces more general than chainable graphs (and graphs), so-called generalized graphs, and we generalize Theorem 3 by showing that an analog version of this theorem holds for generalized graphs, as well.

Suppose A is a topological space. Let be a finite subset of A and let be a finite family of pairs where , , and K is a subspace of A such that K is a Hausdorff continuum chainable from a to b. Suppose

and that the following holds: if , and , then .

Then the triple is called a generalized graph.

Let be a chainable graph and let . We say that a is an endpoint of if there exists a unique such that for some .

If , we can think of K as an edge of the generalized graph . Then, is an endpoint of if it is an endpoint of only one of its edges. Also, we can say that the main difference between a chainable and a generalized graph is that we let the edges of the generalized graph intersect in more than two, yet finitely many, points.

Note that each chainable graph is a generalized graph.

Example 1.

Let

Let and . It is known that K is a continuum chainable from a to b. Therefore, the triple is both a chainable and a generalized graph. Now, let . Since K is also a continuum chainable from b to c, triple is a generalized graph but is not a chainable graph since it does not satisfy the property (ii) from the definition of a chainable graph.

The previous example shows us one more distinction between chainable and generalized graphs. Namely, if is a generalized graph and K is its edge, there can exist different pairs of endpoints of K which is not the case in a chainable graph.

We have shown that there exists triple which is a generalized graph but not a chainable graph. In the next three examples we show even more: there is such space A for which there are and V such that is a generalized graph but there are no such and V for which is a chainable graph.

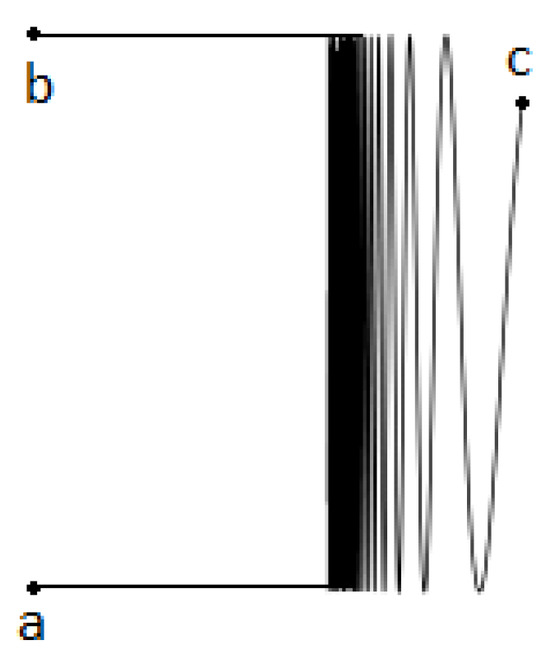

Example 2.

Figure 3.

Set A.

It is easy to see that there exist and V such that is a generalized graph.

Example 3.

Let A be as in Example 2. Assume that there are and V such that is a chainable graph. Then, there are no such that if

To prove so, let us assume the opposite, i.e., let be such that . We will distinguish three cases.

Firstly, let . Let . Since continuum K is chainable from a to b, there is an open ϵ-chain in K which covers K from a to b. If is such that , then

which contradicts the connectednes of the set on the left side of the equation since and are disjoint by the definition of a chain. Namely, if then would mean that

which is a contradiction. Similarly, if , assuming that leads to

a contradiction. Finally, if , we similarly obtain

if .

If , we obtain a contradiction in the same way.

Hence, we are left with the third case when both and contain exactly one of the points a and b which will also leads to a contradiction (and that will prove the claim). Namely, let . Again, since continuum K is chainable from a to b, there is an open ϵ-chain in K which covers K from a to b. Let be such that . Similarly as before we can prove that

which then contradicts the connectedness of the set on the left side of the equation.

Example 4.

Let A be as in Example 2. We are going to show that there are no and V such that is a chainable graph. To prove so, let us assume the opposite. Then, by the definition of the chainable graph, there is such that (otherwise would be an open set in A, which follows easily from the definition of a chainable graph, but it is clear that is not open in A). Since K is connected and for each

This allows us to conclude that for each there is such that . Indeed, let us assume that there exists such that for each it holds . Using (4) we conclude that for there is

i.e., there is , such that

If , by (5) we have that

is a contradiction. Also, if , then there is such that and, because of (5), it is

i.e., which contradicts the assumption. This leaves us with the last case possible, . Using (5), this means that

Now, using (4) and the same arguments as above (K is infinite since it is connected, Hausdorff and ), we conclude that there is such that

Obviously, there is such that , i.e.,

Because is an open set in A (which is not hard to conclude from the definition of a chainable graph), there is such that

Since

we have that

which, again, contradicts the assumption. Hence, for each there is such that .

Now, let be a projection on the first coordinate. A compact and connected is a segment. Since , obviously , and since for each there is such that , there are , such that . Since

and is a bijection, we conclude that

and, therefore,

i.e.,

Now, we show that in (6), equality does not hold. Indeed, let us assume that

If , then . Since , we conclude that

a contradiction. If , as above, we conclude that , i.e., . Therefore, K is chainable from to , so there is an open – chain in K which covers K from to . If is such that , similarly as in Example 3, we obtain that

which is impossible since is connected. Therefore,

which means that

But, we can conclude even more. It is true that

Indeed, if assume the opposite, for example, , then . Since and is a bijection, we obtain that

so

We have and so , which implies that or . In both cases we obtain a contradiction with the fact that K is chainable from a to b, as in Example 3.

So

and we prove that both of these sets are connected. To show that, assume that is not connected. Therefore, there exists a separation of . Without loss of generality, let , so we can write

Both F and G are closed in , and therefore, they are closed in A (since is closed in A). Since , F and G are closed in K. Similarly, is closed in A since is open in A. Therefore, (8) gives us a separation of K which is connected, a contradiction. So, since and is connected and compact, there exists such that

Similarly, there exists such that

i.e.,

which is impossible by Example 3.

In this section we are going to prove the following result:

Theorem 4.

If is a generalized graph and B is the set of all its endpoints, then has computable type.

Remark 2.

Using Remark 1, we conclude the following: if is a generalized graph, B the set of all its endpoints, a topological space and a homeomorphism, then

is generalized graph and is the set of all its endpoints. Namely, if are such that , then , and therefore, is a finite set which, together with the fact that , implies that is a finite set.

Let be a computable topological space and let S and T be subsets of X such that . We say that S is computably enumerable (c.e) up to T if there exists a c.e. subset of such that for each the following holds:

It is obvious that if S is closed and S is c.e. up to S, then S is a c.e. set in .

Remark 3.

Let be a computable topological space and let ,…, and T be subsets of X such that is c.e. up to T for each . Then, it readily follows that …, is c.e. up to T.

Now we are ready to prove Theorem 4. In view of Remark 2 it is enough to prove the following proposition.

Proposition 4.

Let be a computable topological space and let S and T be semicomputable sets in this space. Suppose there are and V such that is a generalized graph and T is the set of all its endpoints. Then, S is computable.

Despite the obvious similarities between chainable and generalized graphs, there are more than slightly differences in the proofs of the main results. In the case of the chainable graph, if we take a continuum (i.e., an edge) K chainable from a to b we know that the intersection with an other edge M can occur only in one of the points a and b, let us say in a, and a is also an endpoint of M, so we can use that fact to write , where are compacts such that and . That is not the case if we have a generalized graph and some technical lemmas are needed in order to solve that problem. So, before giving the proof of Proposition 4, we need certain further facts about chainable continua. Specifically, we have to prove that if it is given a chainable continuum K and its arbitrary point c, we can find a nontrivial subcontinuum L of K which contains c and is small enough. More precisely, we need to show the following:

Lemma 1.

Let be a continuum chainable from a to b, and let be arbitrary. For each there is a nontrivial continuum such that and

Firstly, we give straightforward proofs of a few lemmas needed to prove the aforementioned one.

Lemma 2.

Let be a continuum chainable from a to b. For each there exists an open ϵ-chain in which covers K from a to b such that is also a chain.

Proof.

Since is a continuum chainable from a to b, there exists a compact -chain in which covers K from a to b. Let us define

Since for disjoint sets and , the number is positive.

For each , because is compact, there exist and such that

Let us define

Above the defined are open sets and because of (10) it is , and

and for all such that . In particular, .

Furthermore, for arbitrary , there are such that and . Therefore,

i.e., for each .

It is clear that for all such that and , it is

because otherwise we would have that

which is impossible.

Since, for each ,

we conclude that for all such that . In particular, . Therefore, is an appropriate chain. □

Lemma 3.

Let be a continuum chainable from a to b, and let be arbitrary. For each there exists an open ϵ-chain in which covers K from a to b such that:

- 1.

- is also a chain;

- 2.

- there exists a unique such that .

Proof.

Since is a continuum chainable from a to b, by previous lemma, there is an open -chain in which covers K from a to b such that is also a chain. Let be such that . If then and for each , defines an appropriate chain. Similarly, if the chain is defined by for each , and . Finally, if then the desired chain is . □

Lemma 4.

Let X be a set and let and be two chains in X such that refines . Furthermore, suppose that and are such that , and . Then, there exists such that and .

Proof.

We have since . If the conclusion follows from Lemma 3.8 in [5]. Otherwise, if , the same lemma, only applied on the chain defined by for each , proves the claim. □

In order to prove Lemma 1, one must consider cases when or and when c is neither a nor b. We have the following definition. If and are finite sequences of subsets of a set X, we say that strongly refines if refines , and .

The proof of the following lemma can be found in [4].

Lemma 5.

Let be a compact metric space. Let , where , , be a sequence of chains such that strongly refines and such that for each and for each . Let

Then, S is a continuum chainable from a to b, where , .

The proof of this one can be found in [11].

Lemma 6.

Let be a continuum chainable from a to b, , . Let be arbitrary. Then, there exist and such that , L is a continuum chainable from a to c and .

Now, we give the proof of one more lemma, the crucial one for the proof of Lemma 1.

Lemma 7.

Let be a compact metric space. Let , where , , be a sequence of open chains such that refines , such that for each and for each and such that is also a chain for each .

Let

Then, S is nonempty, connected and compact (i.e., a nonempty continuum).

Proof.

Let us denote

Because refines (and therefore, ), is a descending sequence of closed and nonempty subsets of and since is compact we have , i.e., .

Furthermore, since S is an intersection of closed subsets of , S is also closed in X which, together with the fact that is compact, implies that S is also compact.

Now, we only have to prove that S is connected. Let us assume the opposite, i.e., let be a separation of S. Let

Since A and B are compact and disjoint, we have that . Let be such that for each .

Now, we will define a sequence , where is such that

for each .

Firstly, notice that each element of the chain intersects at most one of the sets A and B. Indeed, let us assume that there exists such that and . Then, for and we have that

which is obviously a contradiction. Therefore, for each , we conclude that

Since is a separation of S and because refines , it is

so there exist such that

Because of (11), we conclude that

Also, (12) implies

Namely, if we assume the opposite, i.e., then . So, for and , we have that

i.e., we obtain a contradiction.

We now show that there exists , such that

Indeed, let us assume the opposite, i.e., that

for each . Firstly, let us assume that . If for each , then by assumption we conclude that for each . Therefore, for some and , we obtain a contradiction similarly as in (15). Now, if there is such that then

is well defined and we can conclude that . Again as before, for some and , we obtain a contradiction. The same conclusions arise if .

Suppose and are such that:

- ;

- ;

- ;

- .

We now show that there exist such that:

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

- (d)

- (e)

Namely, by 3 there is such that

Similarly as before,

so there is such that

Obviously,

Similarly, using 2., we conclude that there exists such that

By (19), (20) and 4., one can easily conclude that

Let us now assume that , i.e., . There exists such that

Indeed, if we assume the opposite, then there exists such that

which together with (17) and (18), implies that , which is a contradiction since , i.e., . Analogously, there is such that

Because of (19) and (20) it is clear that and , so by applying Lemma 4 to (21) and (22), we see that there is , such that

Using similar arguments, we obtain the same conclusion if , i.e., . This concludes the inductive construction of and such that (a)–(e) hold.

Now, to summarize, for each we have found such that In that way, we have constructed a descending sequence of closed subsets of , so there exists

Finally, we give the proof of Lemma 1.

Proof.

If or , the conclusion arises from Lemma 6.

Assume now that . Firstly, we will construct a sequence of open chains , , , such that for each :

- covers K from a to b and for each ;

- is also a chain;

- refines ;

- such that ;

- for each and .

Firstly, we define

By Lemma 3, there is an open -chain in which covers K from a to b such that is also a chain and that there exists a unique such that Obviously, In order for to satisfy all the other conditions, it remains to prove that . Since and , it is

so it follows that , i.e., . Similarly, because

so , i.e., Note that condition 5 implies .

Let us assume that is an open chain in that satisfies properties 1–4. Since is an open cover of , there is a Lebesque number of . Because is a chainable continuum, by Lemma 3 there is an open -chain in which covers K from a to b such that is also a chain and that there is a unique such that . Because for each , refines .

This concludes the recursive construction of the sequence such that 1–5 hold.

Let

Now, for each , we want to choose such that

and

The number is well defined because and for each . Namely, if we assume that , then . Because of properties 3 and 4 we have

i.e., , which is impossible since and . Furthermore, let us assume that there exists such that . This, together with multiple use of (25), implies

So, there exists such that . By (23) and 5, it is and this yields a contradiction since . Similarly, the number is also well defined since and for each . Obviously, .

Now, we are left to prove that .

Let us assume the opposite, i.e., let be such that for each we have . It is clear that since . Furthermore, if , the number r is greater than the maximum defined by (26) which is obviously a contradiction. Similarly, in case , a contradiction is obtained using (27). Therefore, we conclude that . But we can prove even more. Namely, for each

and

Let us assume the opposite of (28), i.e.,

from which, together with (25), we infer that

for some . Because of (26), it is for each . Considering property 3 this implies that

for some . Therefore, because , it is and since (30) and (31) imply , a contradiction is obtained and (28) is proven. Similarly, one can easily show that (29) holds, too.

So, we define

and we conclude, using Lemma 7, that L is a nonempty continuum in .

Now we shall prove that L is nontrivial. Let S be the set of all finite sequences of the form , , such that and for each and let for a sequence ,

It is obvious that S is infinite and because , either or is infinite. Let us define , if is infinite and , otherwise. Obviously, is then infinite. Note that because of (23), . Now, assume that we have defined such that is infinite. Since

we put , if is infinite and , otherwise. It is clear that is infinite. Therefore, we have constructed a sequence , . We can conclude that there is and because

we conclude that . Clearly, . Also, for each , it is , so it is for each . Therefore, . Hence, L is nontrivial.

Now, we are only left to prove that , which is clear since

and

This concludes the proof. □

Now, we are ready to prove Proposition 4.

Proof.

Suppose , because otherwise the claim is clear. Recall that S has to be metrizable. Let d be the metric on S which induces the topology on S (the relative topology on S in . For each , K is a Hausdorff continuum chainable from a to b, and therefore, the metric space is a continuum chainable from a to b. Let

Then, by the definition of a generalized graph

Since and are compact in and disjoint, by Theorem 1 there exists such that

Together with (32), we have that

which means that is semicomputable in . Since it is finite, Proposition 2 implies that is computable. In particular, it is c.e. so it is (trivially) c.e. up to S.

In order to prove that S is c.e. in , we want to prove that K is c.e. up to S for each . In that way, S will be a c.e. up to itself as a finite union of such sets, and therefore, a c.e. set. Together with the fact that S is semicomputable (by assumption), S will be computable and the proof will be completed.

So, let be arbitrary. Then, there are such that . For the sake of simplicity, we will denote

Note that each endpoint is a computable point by Proposition 2, since T is semicomputable and finite.

Let us assume that . Then a and b are endpoints of , so a and b are computable points. If , then , so K is semicomputable by the assumption. Hence, K is computable as a semicomputable chainable continuum with computable endpoints [3], in particular, K is c.e. up to S. But if , then equality

implies, similarly as before, that there exists such that , and therefore, K is semicomputable. As in the previous case we conclude that K is c.e. up to S.

Now, assume that and let us denote

i.e., let be the set of all elements of K such that they are also contained in some , . Obviously, is finite (by the definition of a generalized graph).

Let us first suppose that . Then, for each we have , i.e.,

Since is a finite union of compact sets, it is also compact and obviously disjoint from K so, as before, we have for some . It follows that K is a semicomputable continuum chainable from a to b, where both a and b are computable points (a and b are endpoints of since ). Therefore, K is a computable set and, in particular, c.e. up to S.

Finally, consider the case Let us enumerate the set , i.e., let

for , , and let

Using the definition of it follows that for all such that we have

Now, we want to prove that the sets A and B defined by

and

are disjoint and both compact in .

Firstly, B is compact in as a finite union of compact sets (a closed ball in a compact S is also compact). To prove that A is compact, it is clearly enough to prove the following identity:

Since

to prove (39), we only have to prove the non trivial inclusion.

So, assume that

It is clear that

so in order to prove that , it suffices to show that

Indeed, let us assume the opposite, i.e., . Then, obviously . Also, there is no such that because then there would exist such that which would contradict (41). Hence, , i.e., , which contradicts (40). So .

Since (39) holds, A is compact in . It is obvious that . So, since A and B are disjointed and compacted in , by Theorem 1 there are such that

and

Hence,

which, together with (37) and (38), implies that

Now, we distinguish four cases depending on whether a and/or b are elements of .

Firstly, suppose . Then, without loss of generality we may assume that and . Since , there is , such that . Similarly, there is , such that . By Lemma 1 there are nontrivial continua and such that

and

Because L and N are connected and and , is also connected. Furthermore, by (42)–(44) we conclude that

Moreover,

Indeed, if we assume that then we have (because and ). By (46), we obtain , i.e., which is not true. Combining (46) and (47) we obtain that

so, by Theorem 1, there exists such that

and

Similarly, there exist , and such that

and

Let and be the subsets of from Theorem 1 and let be a recursive function such that for each .

Now, let be such that . Then, . Namely, if we assume the opposite, i.e., , then is finite, and therefore, closed in K. Since it is also open in K and K is connected, we have . Now, because K is finite and Hausdorff it is discrete and this is a contradiction with the fact that K is connected and ().

So, there exist and such that

Furthermore, since is a continuum chainable from a to b, there is a compact r-chain in which covers K and such that and .

Without loss of generality (as in the proof of Lemma 3) we may assume that

Let be such that . It follows from (52) and that

Because of the definition of r, we also conclude that so

for each This, in particular, implies that

Let us now define

and

Sets and G are all compact since is compact.

Note that for each , by (36), we have that

Now, for each , since

it holds, for each ,

and then

Similarly we have that

for . This, together with (36) and the fact that is a chain implies that the sets F and G are disjointed.

Using (57), one can easily show that

By (48) and (50) we have that and . Therefore, there exist such that , , , , , and . Note that, by (42) and (59), it holds .

So, if is such that , then there exist such that:

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- ;

- (iii)

- ;

- (iv)

- ;

- (v)

- .

Let be the set of all for which the statements (i)–(v) hold. Since is a semicomputable set in , the set of all such that (i) holds is a c.e set. Now, it follows easily that is a c.e. set. Let be the set of all for which there exist such that . Then, is c.e by the Projection theorem.

On the other hand, suppose . Then, there exist such that (i)–(v) hold. We want to prove that .

Suppose the opposite, i.e., . Since by (iii), we have

and, by (45), it holds

Clearly and are open in and disjointed. Since is connected, in order to yield a contradiction, it is enough to show that both and intersect . It is clear that . By (51) , therefore, because of (v), we have so . Similarly, by (49), and a contradiction is obtained, i.e., . We have proven the following:

This means that K is c.e. up to S.

Now suppose and . Similarly as before, we conclude that b is a computable point in and we can assume that .

Again, since , there is , such that . By Lemma 1, there is a nontrivial continuum such that

Now, choose , . Similarly, as before, we obtain

so by Theorem 1 there exists such that

and

Suppose is such that . Similarly, as before, there exist and such that

Furthermore, since is a continuum chainable from a to b, there is a compact r-chain in which covers K from a to b. Let be such that . For each let be such that . We have for each and

As above, we define

and

Now, the same as earlier, we conclude that the sets and G are compact in and that

Note that, by (64) and (42), it holds .

So, if is such that , then there exist such that:

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- ;

- (iii)

- ;

- (iv)

- ;

- (v)

- .

Let be the set of all for which the statements (i)–(v) hold and let be the set of all for which there exist such that . Since b is a computable point, the set of all such that (v) holds is a c.e set. Now, it follows easily that is a c.e. set and then is also c.e.

On the other hand, suppose . Then, there exist such that (i)–(v) hold. We claim that . Suppose the opposite, i.e., . Since by (iii), then

and, because of (60),

Clearly and are open and disjointed. Since is connected, in order to yield a contradiction, it is enough to show that both and intersect , which is clear since , by (v) and (otherwise, would by (iv) mean that , which contradicts (62)). Hence, . To summarize,

and

i.e., K is c.e. up to S.

Now, we are left with the last case: . Obviously so both a and b are computable points.

Suppose is such that . Similarly, as before, there exist and such that

Furthermore, since is a continuum chainable from a to b, there exists a compact r-chain in which covers K from a to b. Let be such that . It follows

In the same way as before, we define the sets F and G and conclude that there exist such that:

- (i)

- ;

- (ii)

- ;

- (iii)

- ;

- (iv)

- ;

- (v)

- .

Let be the set of all for which the statements (i)–(v) hold and let be the set of all for which there exist such that . As before, it follows that is a c.e. set and that is also c.e.

On the other hand, suppose . Then, there exist such that (i)–(v) hold. We want to show that . Suppose . Since by (iii), we have

It follows , and , which is impossible since K is connected. So . We have proved that

and

i.e., K is c.e. up to S.

We conclude that each is c.e. up to S. As stated before, that is enough to obtain that S is computable in . □

4. Discussion

In this paper, we have shown that the topological pair of a generalized graph and the set of its endpoints has a computable type. A notion of a generalized graph is inspired by a notion of a graph—a union of finitely many arcs such that distinct arcs intersect in at most one endpoint. However, by the definition of a generalized graph, we let its edges intersect in multiple points as long as there are finitely many of them. A question arises naturally—if we allow infinite intersections of edges, can we state an analogous result for such an object. The answer is negative. Namely, there is continuum in chainable from to which intersects continuum chainable from to in inifinitely many, yet countable, points. Union is a semicomputable set that is not computable (see Example 6.2 in [36]). In fact, and are arcs.

In [7] the authors examined the strong computable type. We will now describe the notion of the strong computable type using terminology from recursive function theory.

Let be any class of functions () such that contains initial (basic) functions and is closed to composition, primitive recursion and the -operator. Note that any (total) computable function belong to . We say that is c.e. relative to if or , where is a function such that each component function of f belongs to . If is a computable topological space and S is a closed set in , we say that S is c.e. in relative to if the set is c.e. relative to . A compact set S in is said to be semicomputable in relative to if the set is c.e. relative to . Finally, S is computable in relative to if it is both c.e. and semicomputable relative to .

We say that a topological space A has strong computable type if in any computable topological space for any the following holds: if S is semicomputable in relative to and S is homeomorphic to A, then S is computable in relative to . We say that a topological pair has a strong computable type if in any computable topological space for any the following holds: if S and T are semicomputable in relative to and is homeomorphic to , then S is computable in relative to .

It is straightforward to check that all proofs in this paper also work if, instead of computable functions, we use functions from any fixed class (where is a class with the property described above). We conclude the following: if is a generalized graph and B is the set of all its endpoints, then has strong computable type.

Also, we would like to highlight how this result helps us to better understand the relationship between computability and topology. We know that for a semicomputable set, in order to be a computable one, it suffices to be computably enumerable, but this is usually not easy to check. Sometimes, the topological properties of a semicomputable set are strong enough that they, together with some additional conditions, imply the computability of the whole set. We have proven that in the case of a generalized graph, computable enumerability (and, therefore, the computability) of the set as a whole follows from the mere topological structure of the set and from the computability of the finitely many specific points (endpoints). Other known results on the computable type also show that there is a strong relationship between topology and computability theory.

In the end, let us mention that in a computable metric space, a semicomputable arc (which, in general, is not computable) can always be approximated by a computable subarc with arbitrary given precision (in the sense of the Hausdorff metric). Moreover, a similar statement holds for semicomputable decomposable chainable continua, see [5]. In view of this, a natural question is as follows: what can be said about approximations of semicomputable generalized graphs by computable generalized graphs? This can be a further direction of investigation regarding the topic of generalized graphs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.I. and M.J.; methodology, Z.I. and M.J.; formal analysis, Z.I. and M.J.; investigation, Z.I. and M.J.; resources, Z.I.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.; writing—review and editing, Z.I.; supervision, Z.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Miller, J.S. Effectiveness for Embedded Spheres and Balls. Electron. Notes Theor. Comput. Sci. 2002, 66, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specker, E. Der Satz vom Maximum in der rekursiven Analysis. In Constructivity in Mathematics; Heyting, A., Ed.; North Holland Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1959; pp. 254–265. [Google Scholar]

- Čičković, E.; Iljazović, Z.; Validžić, L. Chainable and circularly chainable semicomputable sets in computable topological spaces. Arch. Math. Log. 2019, 58, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iljazović, Z. Chainable and Circularly Chainable Co-c.e. Sets in Computable Metric Spaces. J. Univers. Comput. Sci. 2009, 15, 1206–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Iljazović, Z.; Pažek, B. Computable intersection points. Computability 2018, 7, 57–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, D.E.; Hoyrup, M. Computability of finite simplicial complexes. In Proceedings of the 49th International Colloquium on Automata, Languages, and Programming (ICALP 2022), Paris, France, 4–8 July 2022; Schloss Dagstuhl—Leibniz Center, Dagstuhl Publishing: Wadern, Germany, 2022; Volume 111, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, D.E.; Hoyrup, M. Strong computable type. Computability 2023, 12, 227–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattka, V. Plottable real number functions and the computable graph theorem. SIAM J. Comput. 2008, 38, 303–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kihara, T. Incomputability of Simply Connected Planar Continua. Computability 2012, 1, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H. On a Π01 set of positive measure. Nagoya Math. J. 1970, 38, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iljazović, Z.; Jelić, M. Computability of chainable graphs. Rad HAZU, 2024; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Iljazović, Z. Computability of graphs. Math. Log. Q. 2020, 66, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, D.E. Computability of Topological Space. Doctoral Thesis, Université de Lorrain, Metz, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Brattka, V. The Discontinuity Problem. J. Symb. Log. 2023, 88, 1191–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattka, V.; Weihrauch, K. Computability on subsets of Euclidean space I: Closed and compact subsets. Theor. Comput. Sci. 1999, 219, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, R.G.; Melnikov, A.G. Computably compact metric spaces. Bull. Symb. Log. 2023, 29, 170–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, D.S.; Zhong, N. Robust non-computability of dynamical systems and computability of robust dynamical systems. Log. Methods Comput. Sci. 2024, 20, 170–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertling, P. Effectivity and effective continuity of functions between computable metric spaces. In Combinatorics, Complexity and Logic: Proceedings of the 1st International Conference: DMTCS96; Bridges, D.S., Calude, C., Gibbons, J., Witten, I.I., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1996; pp. 264–275. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyrup, M. The fixed-point property for represented spaces. Ann. Pure Appl. Log. 2022, 173, 170–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreisel, G.; Lacombe, D. Ensembles récursivement measurables et ensembles récursivement ouverts ou fermé. Compt. Rend. Acad. Des Sci. Paris 1957, 245, 1106–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux, S.; Ziegler, M. Singular coverings and non-uniform notions of closed set computability. Math. Log. Q. 2008, 54, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McNicholl, T.H. A Note on the Computable Categoricity of lp Spaces. In Evolving Computability; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 268–275. [Google Scholar]

- McNicholl, T.H. The Power of Backtracking and the Confinement of Lenght. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 2013, 141, 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, A.G. Computably isometric spaces. J. Symb. Log. 2013, 78, 1055–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnikov, A.G.; Ng, K.M. Separating notions in effective topology. Int. J. Algebra Comput. 2023, 33, 1687–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Tsujji, Y.; Yasugi, M. Computability structures on metric spaces. In Combinatorics, Complexity and Logic: Proceedings of the 1st International Conference: DMTCS96t; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1996; pp. 351–362. [Google Scholar]

- Pour-El, M.B.; Richards, J.I. Computability in Analysis and Physics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Turing, A.M. On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem. Proc. Lond. Math. Soc. 1936, 42, 230–265. [Google Scholar]

- Weihrauch, K. Computability on computable metric spaces. Theor. Comput. Sci. 1993, 113, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihrauch, K. Computable Analysis; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Weihrauch, K. Intersection points of planar curves can be computed. Computability 2022, 11, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasugi, M.; Mori, T.; Tsujji, Y. Effective properties of sets and functions in metric spaces with computability structure. Theor. Comput. Sci. 1999, 219, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihrauch, K.; Grubba, T. Elementary Computable Topology. J. Univ. Comput. Sci. 2009, 15, 1381–1422. [Google Scholar]

- Weihrauch, K. Computable Separation in Topology, from T0 to T2. J. Univ. Comput. Sci. 2010, 16, 2733–2753. [Google Scholar]

- Iljazović, Z.; Sušić, I. Semicomputable manifolds in computable topological spaces. J. Complex. 2018, 45, 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čelar, M.; Iljazović, Z. Computability of glued manifold. J. Log. Comput. 2022, 32, 65–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).