On Linear Codes over Local Rings of Order p4

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

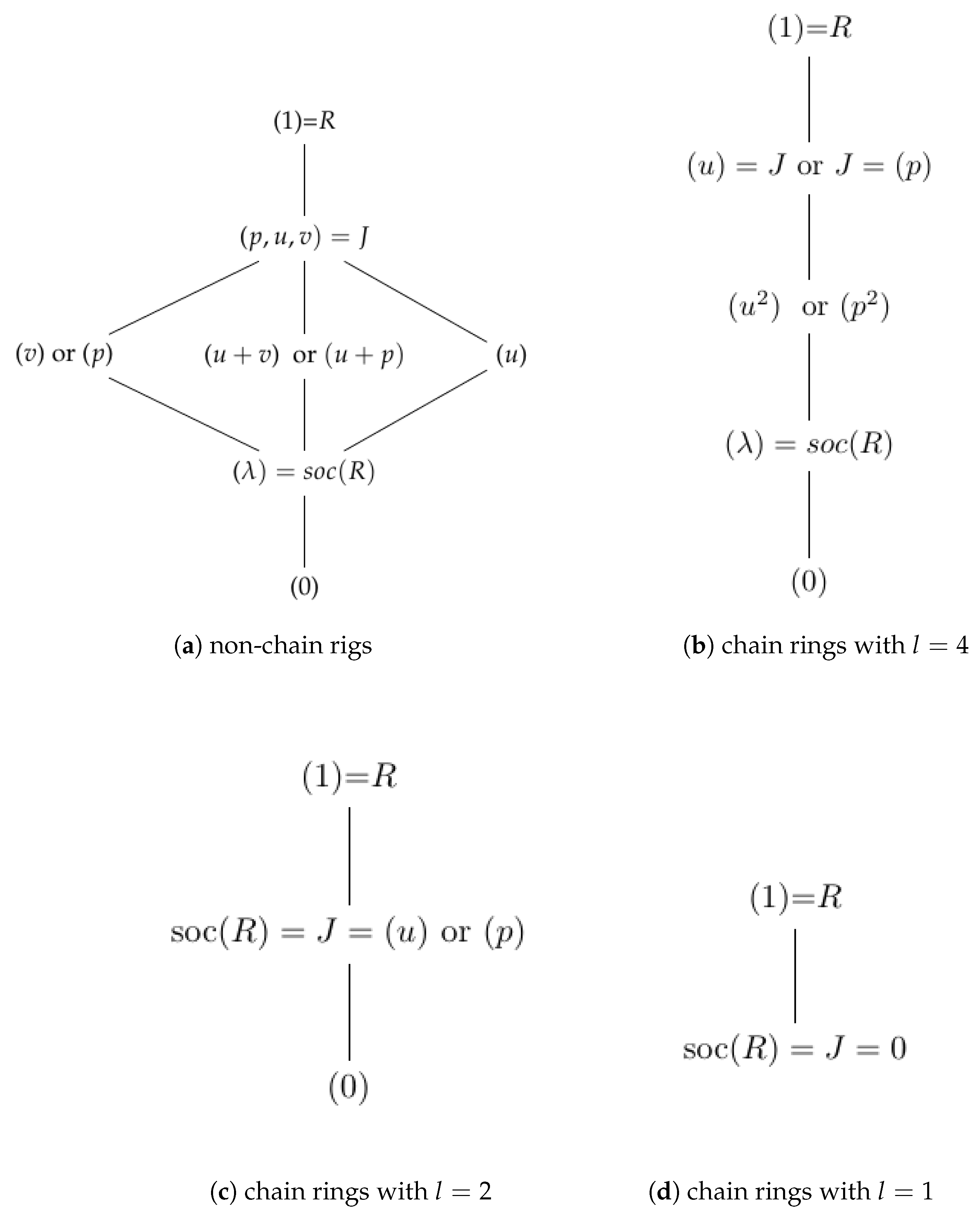

3. Local Rings of Order

- Case a: when Then, we have and Moreover, Consider the following subcases depending on the values that n can take.

- Case a2: if In this case, Based on Equation (6), i.e., or 2 according to which have the following solutions:

- Case a4: if SinceThere is only one ring of such R, and it is Frobenius.

- Case b: if we have and thus Meanwhile, if thenThis ring is unique and Frobenius. Now, assume that then and henceThe ring is a unique and Frobenius ring with soc

- Case c: if then Thus, there exists a unique copy of which is

- (i)

- The number of classes of such rings is as follows:

- (ii)

- With respect to Frobenius rings, we have as

4. MacWilliams Identities

- 1.

- When

- 2.

- WhenFor simplicity, we denote and as follows:

5. Generator Matrices

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alkhamees, Y.; Alabiad, S. The structure of local rings with singleton basis and their enumeration. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDoland, B. Finite Rings with Identity; Marcel Dekker Incorporated: Norman, OK, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendran, R. Finite associative rings. Compos. Math. 1969, 21, 195–229. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, G.; Salagean, A. On the structure of linear cyclic codes over finite chain rings. Appl. Algebra Eng. Commun. Comput. 2000, 10, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, H.; López-Permouth, S. Cyclic and negacyclic codes over finite chain rings. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 2004, 50, 1728–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabiad, S.; Alkhamees, Y. Constacyclic codes over finite chain rings of characteristic p. Axioms 2021, 10, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.A. Duality for modules over finite rings and applications to coding theory. Am. J. Math. 1999, 121, 555–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honold, T. Characterization of finite Frobenius rings. Arch. Math. 2001, 76, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, B.; Karadeniz, S. Linear codes over ℤ4 + uℤ4: MacWilliams identities, projections, and formally self-dual codes. Finite Fields Their Appl. 2014, 27, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriwirach, W.; Klin-Eam, C. Repeated-root constacyclic codes of length 2ps over 𝔽pm + u𝔽pm + u2𝔽pm. Cryptogr. Comm. 2021, 13, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaouine, J.; Charkani, M.E.; Wang, L. Complete classification of repeated-root-constacyclic codes of prime power length over . Discrete Math. 2021, 344, 112325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Guillén, C.A.; Rentería-Márquez, C.; Tapia-Recillas, H. Constacyclic codes over finite local Frobenius non-chain rings with nilpotency index 3. Finite Fields Their Appl. 2017, 43, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greferath, M. Cyclic codes over finite rings. Discrete Math. 1997, 177, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Zhu, S.; Yang, S. A class of optimal p-ary codes from one-weight codes over Fp[u](um). J. Frankl. Inst. 2013, 350, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, S.T.; Saltürk, E.; Szabo, S. Codes over local rings of order 16 and binary codes. Adv. Math. Commun. 2016, 10, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, S.T.; Saltürk, E.; Szabo, S. On codes over Frobenius rings: Generating characters, MacWilliams identities and generator matrices. Appl. Algebra Eng. Commun. Comput. 2019, 30, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moro, E.; Szabo, S. On codes over local Frobenius non-chain rings of order 16. In Noncommutative Rings and Their Applications; Contemporary Mathematics; Dougherty, S., Facchini, A., Leroy, A., Puczylowski, E., Solé, P., Eds.; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2015; Volume 634, pp. 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Alabiad, S.; Alhomaidhi, A.A.; Alsarori, N.A. On Linear Codes over Finite Singleton Local Rings. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Frobenius Rings | ||

|---|---|---|

| Non-Chain | Chain | Non-Frobenius Rings |

| Ring | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ring | soc | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alabiad, S.; Alhomaidhi, A.A.; Alsarori, N.A. On Linear Codes over Local Rings of Order p4. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3069. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12193069

Alabiad S, Alhomaidhi AA, Alsarori NA. On Linear Codes over Local Rings of Order p4. Mathematics. 2024; 12(19):3069. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12193069

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlabiad, Sami, Alhanouf Ali Alhomaidhi, and Nawal A. Alsarori. 2024. "On Linear Codes over Local Rings of Order p4" Mathematics 12, no. 19: 3069. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12193069

APA StyleAlabiad, S., Alhomaidhi, A. A., & Alsarori, N. A. (2024). On Linear Codes over Local Rings of Order p4. Mathematics, 12(19), 3069. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12193069