Convergence Analysis for an Online Data-Driven Feedback Control Algorithm

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. An Efficient Algorithm for Data-Driven Feedback Control

2.1. Problem Setting for the Data-Driven Optimal Control Problem

2.2. The Algorithm for Solving the Data-Driven Optimal Control Problem

2.2.1. The Optimization Procedure for Optimal Control

2.2.2. Numerical Approach for Data-Driven Feedback Control by PF-SGD

- Numerical Schemes for FBSDEs

- Particle Filter Method for Conditional Distribution

- Stochastic Optimization for Control Process

| Algorithm 1 PF-SGD algorithm for data-driven feedback control problem. |

|

3. Convergence Analysis

3.1. Notations and Assumptions

- Notations

- We use to denote the control process starts from time and ends at time T. We useto denote the collection of the admissible controls starting at time .

- We define the control at time to be , the conditional distribution coming from a particle filter algorithm.

- We define where the superscript means that the measure is obtained through the particle filter method, and so it is random.

- We use to denote the sampling operator: and to denote the updating step in the particle filter. We use to denote the transition operator (the prediction step) under the SGD–particle filter framework. is the deterministic transition operator for the exact case (the control is exact in SDG). We mention “deterministic” here to distinguish the case where the control may be random due to the SGD optimization algorithm.

- We use to denote the deterministic inner product, i.e., if , then

- We define . We then have . We remark that is a process that starts from time , and so is essentially the initial condition of the diffusion process.

- We define the distance between two random measures to be the following:where the expectation is taken over by the randomness of the measure.

- We use the total variation distance between two deterministic probability measures :

- We use to denote the total number of iterations taken in the SGD algorithm at time ; we use to denote the total number of particles in the system. We use C to denote a generic constant which may vary from line to line.

- Abusing the notation, we will denote in the following way where the argument can be a vector of any length :

- Assumptions

- We assume that satisfy the following strong condition: for any , there exist a constant such that for all :Notice that (30) implies that such inequality is true for any , and it can be seen from simply fixing all the , to be 0.This is a very strong assumption, and one should consider relaxing it toThat is, this relation holds in expectation instead of point-wise.

- Both b and are deterministic and in in space variable x and control u.

- are all uniformly Lipschitz in and uniformly bounded.

- satisfies the uniform elliptic condition.

- The initial condition .

- The terminal (Loss) function is and positive, and has the most linear growth at infinity.

- We assume that the function (related to the Bayesian step) has the following bound: there exists such that

3.2. The Convergence Theorem for the Data-Driven Feedback Control Algorithm

- The randomness comes from the selection on the initial point .

- The randomness comes from the pathwise approximated Brownian motion used for FBSDEs.

- The randomness comes from the accumulation of the past particle sampling.

4. Numerical Example

4.1. Example 1. Linear Quadratic Control Problem with Nonlinear Observations

4.1.1. Experimental Design

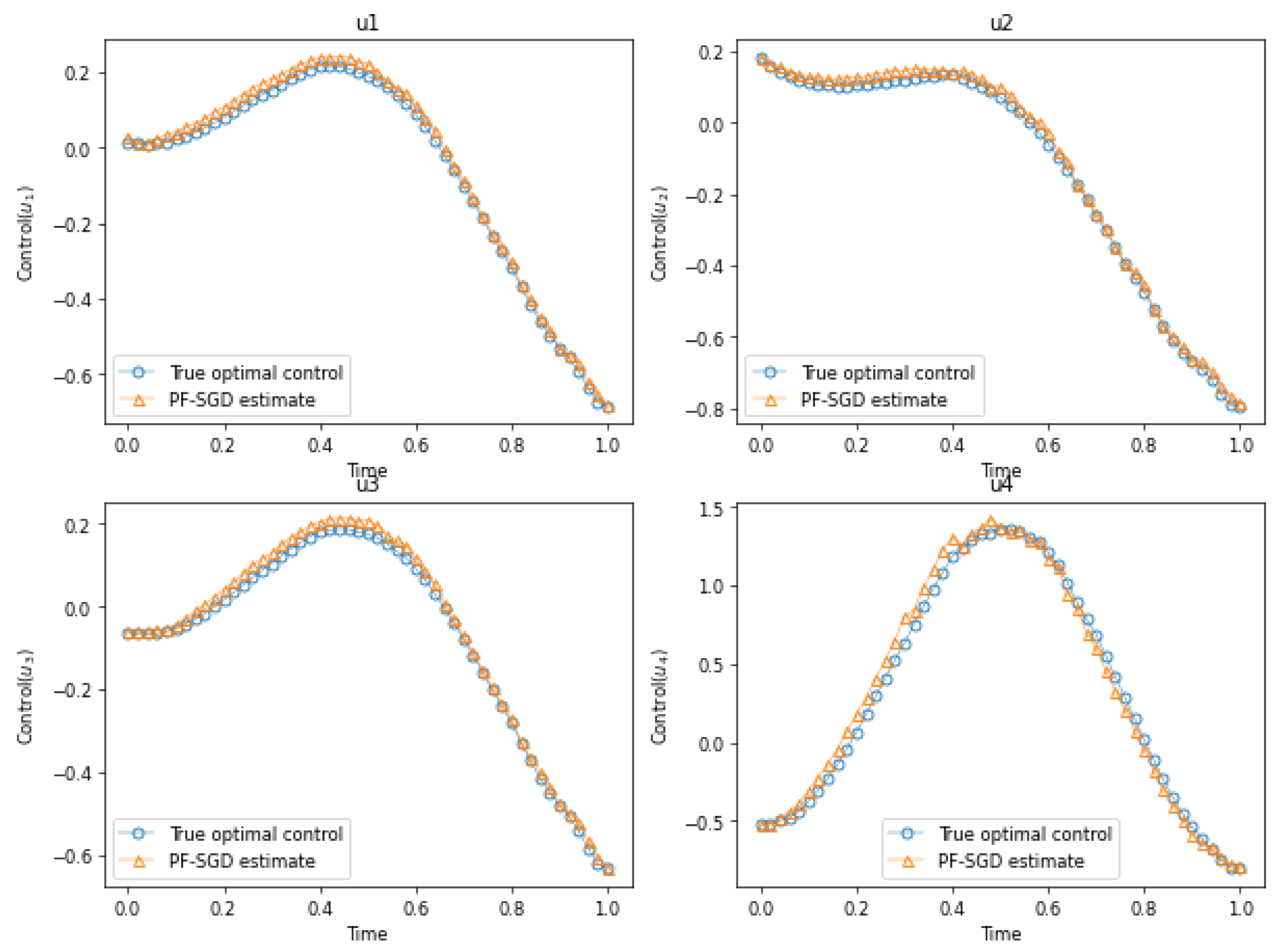

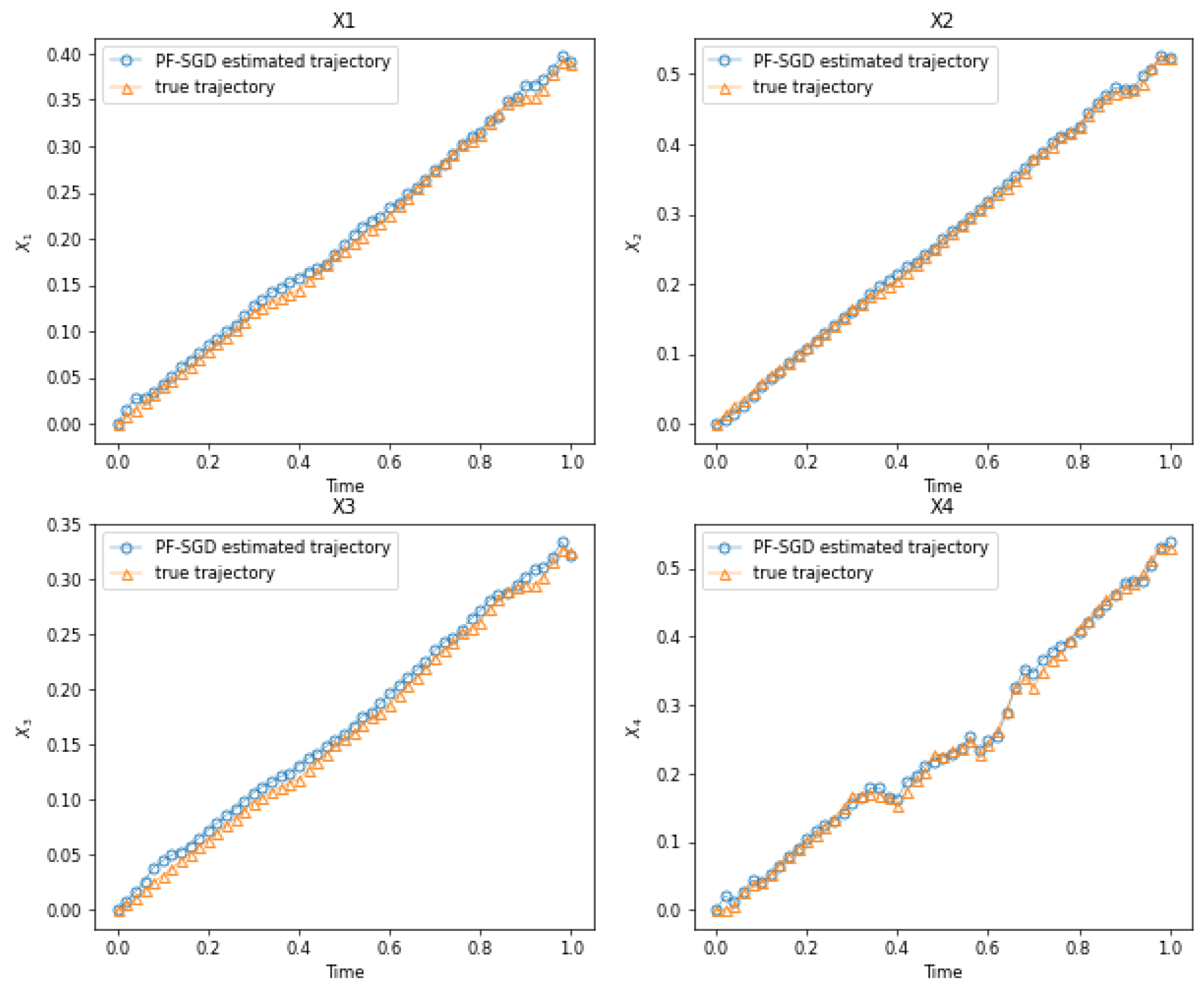

4.1.2. Performance Experiment

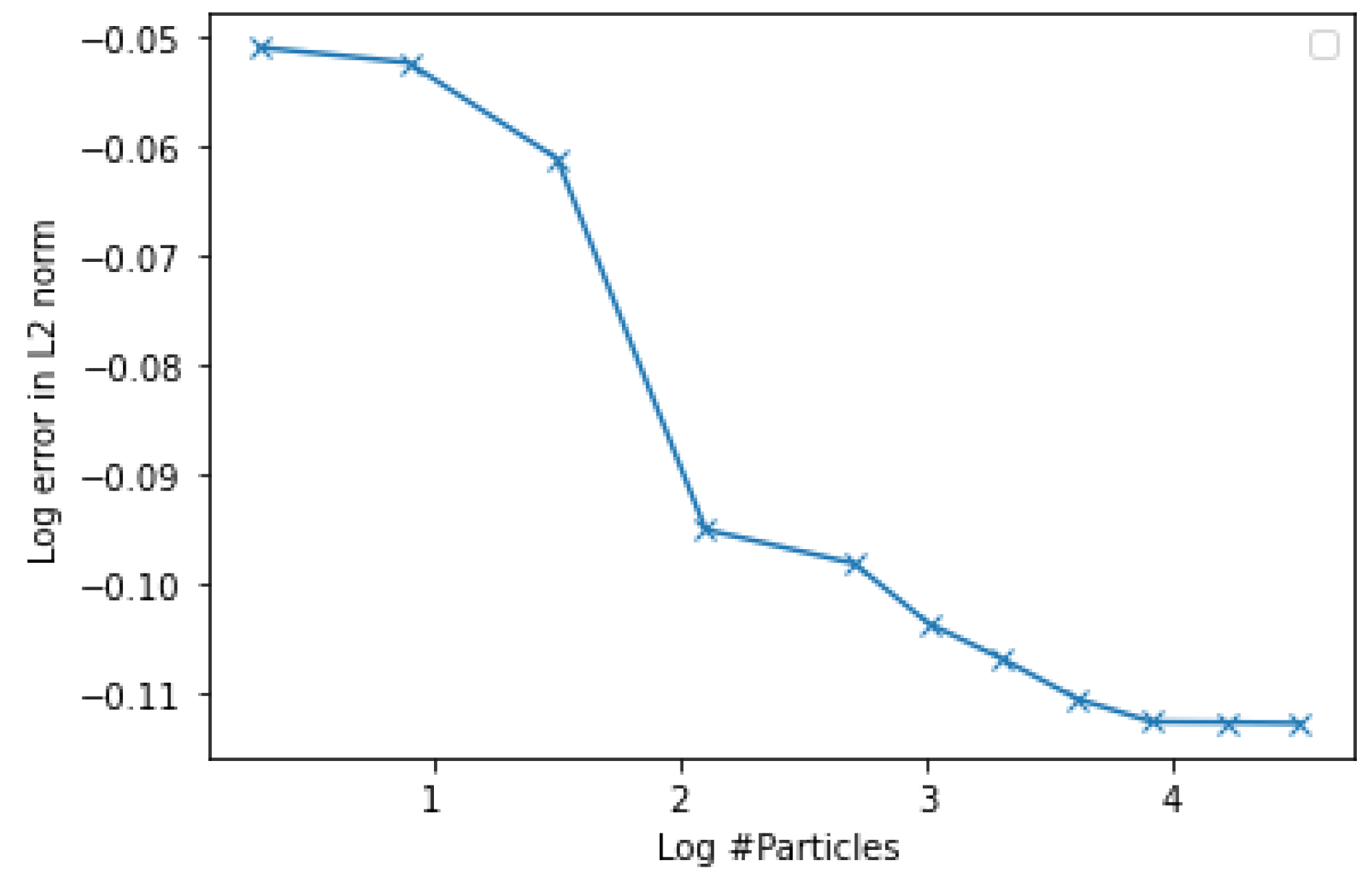

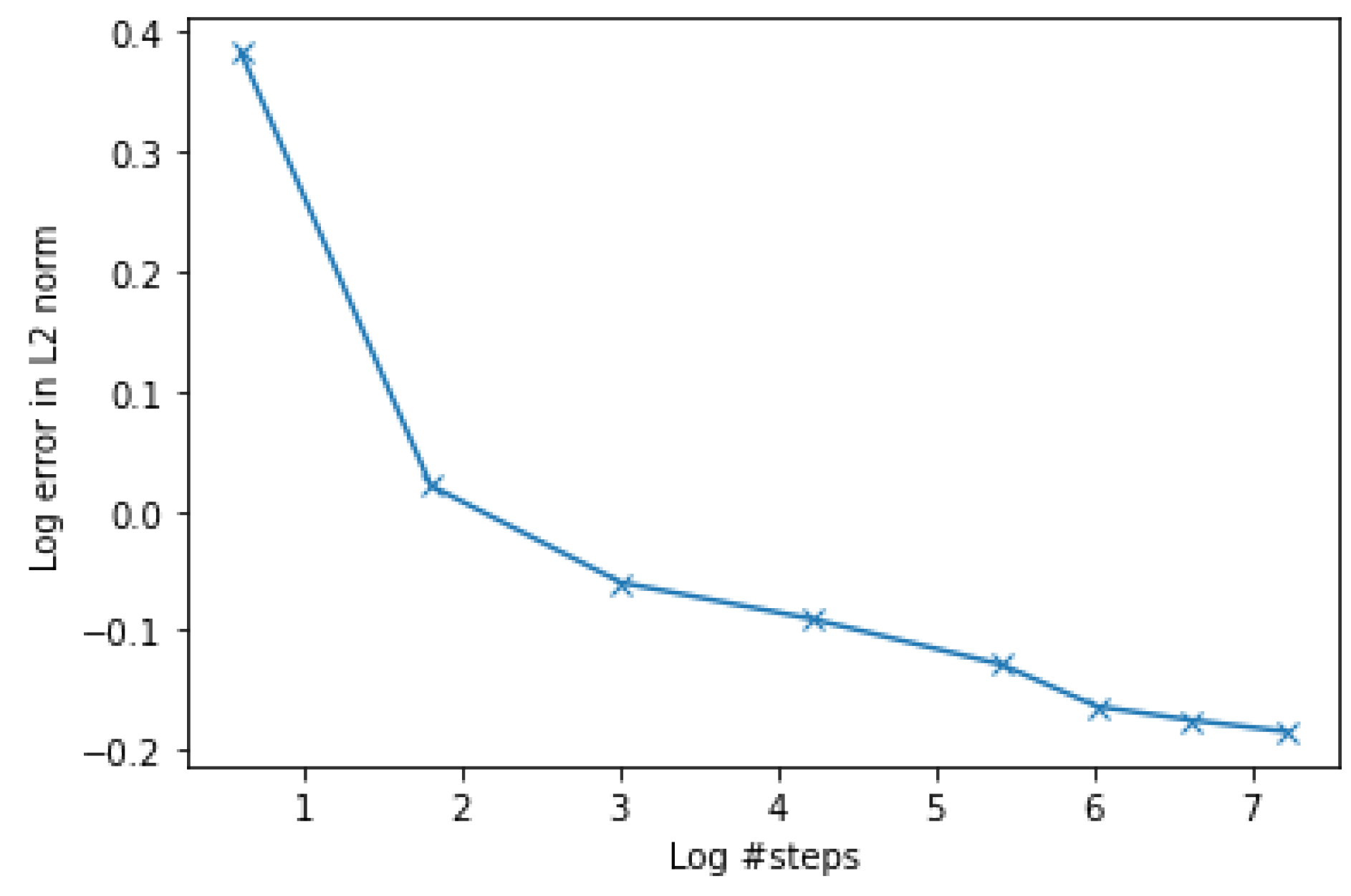

4.1.3. Convergence Experiment

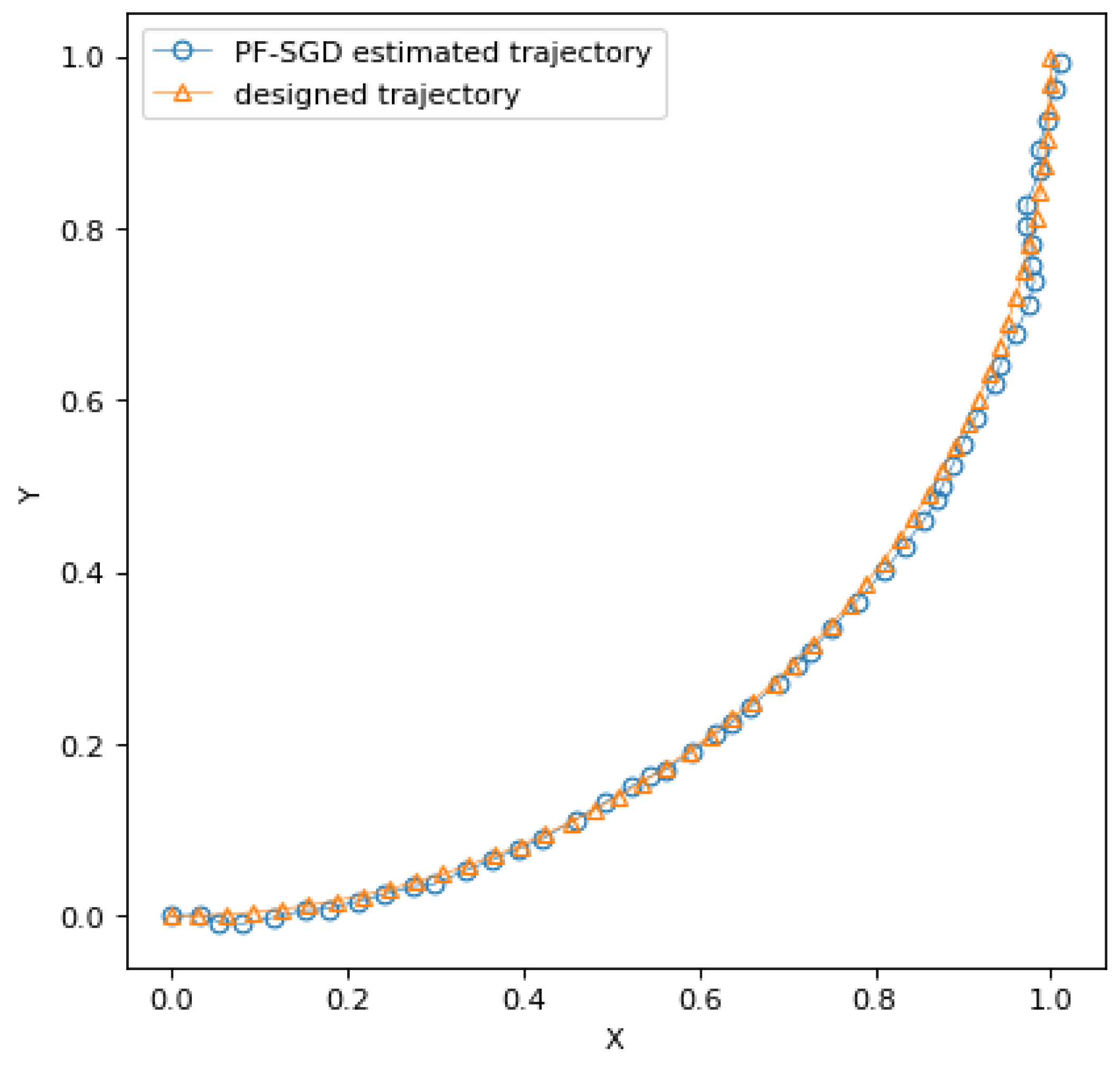

4.2. Example 2. Two-Dimensional Dubins Vehicle Maneuvering Problem

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BSDEs | Backward stochastic differential equations |

| FBSDEs | Forward–backward stochastic differential equations |

| PF | Particle filter |

| SGD | Stochastic gradient descent |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

References

- Archibald, R.; Bao, F.; Yong, J.; Zhou, T. An efficient numerical algorithm for solving data driven feedback control problems. J. Sci. Comput. 2020, 85, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellman, R. Dynamic programming. Science 1966, 153, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Glowinski, R.; Neilan, M. Recent developments in numerical methods for fully nonlinear second order partial differential equations. SIAM Rev. 2013, 55, 205–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S. A general stochastic maximum principle for optimal control problems. SIAM J. Control Optim. 1990, 28, 966–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.; Zhou, X.Y. Stochastic Controls: Hamiltonian Systems and HJB Equations; Springer Science & Business Media: Cham, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, B.; Liu, W.; Tang, T.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, T. An efficient gradient projection method for stochastic optimal control problems. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2017, 55, 2982–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S. The maximum principle for partially observed optimal control of stochastic differential equations. SIAM J. Control Optim. 1998, 36, 1596–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. A numerical scheme for BSDEs. Ann. Appl. Probab. 2004, 14, 459–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Fu, Y.; Zhou, T. New kinds of high-order multistep schemes for coupled forward backward stochastic differential equations. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2014, 36, A1731–A1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, R.; Bao, F.; Yong, J. A stochastic gradient descent approach for stochastic optimal control. East Asian J. Appl. Math. 2020, 10, 635–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, I.; Nakagawa, H. Approximation analysis of stochastic gradient Langevin dynamics by using Fokker-Planck equation and Ito process. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Beijing, China, 21–26 June 2014; Volume 32, pp. 982–990. [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, A.; Wardi, Y. Convergence analysis of gradient descent stochastic algorithms. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 1996, 91, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, R.; Bao, F.; Cao, Y.; Sun, H. Numerical analysis for convergence of a sample-wise backpropagation method for training stochastic neural networks. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2024, 62, 593–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakai, M. On the optimal filtering of diffusion processes. Z. Wahrscheinlichkeitstheorie Verw. Gebiete 1969, 11, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, N.J.; Salmond, D.J.; Smith, A.F. Novel approach to nonlinear/non-Gaussian Bayesian state estimation. IEE Proc. F (Radar Signal Process.) 1993, 140, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morzfeld, M.; Tu, X.; Atkins, E.; Chorin, A.J. A random map implementation of implicit filters. J. Comput. Phys. 2012, 231, 2049–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrieu, C.; Doucet, A.; Holenstein, R. Particle Markov chain Monte Carlo methods. J. R. Statist. Soc. B 2010, 72, 269–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisan, D.; Doucet, A. A survey of convergence results on particle filtering methods for practitioners. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2002, 50, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Künsch, H.R. Particle filters. Bernoulli 2013, 19, 1391–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, F.; Cao, Y.; Meir, A.; Zhao, W. A first order scheme for backward doubly stochastic differential equations. SIAM/ASA J. Uncertain. Quantif. 2016, 4, 413–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhou, T.; Kong, T. High order numerical schemes for second-order FBSDEs with applications to stochastic optimal control. Commun. Comput. Phys. 2017, 21, 808–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.; Stuart, A.; Zygalakis, K. Data Assimilation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, S.; Sun, H.; Archibald, R.; Bao, F. Convergence Analysis for an Online Data-Driven Feedback Control Algorithm. Mathematics 2024, 12, 2584. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12162584

Liang S, Sun H, Archibald R, Bao F. Convergence Analysis for an Online Data-Driven Feedback Control Algorithm. Mathematics. 2024; 12(16):2584. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12162584

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Siming, Hui Sun, Richard Archibald, and Feng Bao. 2024. "Convergence Analysis for an Online Data-Driven Feedback Control Algorithm" Mathematics 12, no. 16: 2584. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12162584

APA StyleLiang, S., Sun, H., Archibald, R., & Bao, F. (2024). Convergence Analysis for an Online Data-Driven Feedback Control Algorithm. Mathematics, 12(16), 2584. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12162584