Abstract

We study a likelihood ratio test for testing the conditional mean of a class of piece-wise stationary CHARN models. We establish the locally asymptotically normal (LAN) structure of the family of likelihoods under study. We prove that the test is asymptotically optimal, and we give an explicit form of its asymptotic local power. We describe an algorithm for detecting change points and estimating their locations. The estimates are obtained as time indices, maximizing the estimate of the local power. The simulation study we conduct shows the good performance of our method on the examples considered. This method is also applied to a set of financial data.

MSC:

62M10; 62M02; 62M05; 62F03; 62F05

1. Introduction

Let and . Assume the observations issued from the following piece-wise stationary CHARN model (see, e.g., [1])

with

where for is a stationary and ergodic process; , and are real-valued functions with the , , are potential instants of changes with and ; for , and for ; for the processes and are mutually independent; is standard white noise with density f. , , ; , ; for and , stands for and The class of models (2) is very large. It contains models such as AR(p), ARCH(p), EXPAR(p), and GEXPAR(p) whose statistical and probability properties are widely studied in the literature (see, e.g., [2] for a study of the ergodicity of GEXPAR models).

As noted in [3], the assumption that and are independent can be extended to some weak dependence assumption. In this paper, for and depending on the s, we construct a likelihood ratio test for testing

A particular case of this work is studied in [4]. The literature on change points is extensive and varied. Some basic notions and theory are presented in [5], where one can find number of references on the first works on the subject. Most of the recent papers on change points are in time series or regression contexts. Various methods and techniques are used for the study. Ref. [6] proposes a test for parameter changes. The observations are assumed to follow an exponential distribution. The author presents a derivation using the method of [7]. Ref. [8] studies the problem of changes in the parameters of AR models and the variance in the white noise using the likelihood ratio statistic. Ref. [9] proposes test statistics for detecting a break in the trend function of a dynamic univariate time series. The tests are based on the mean and exponential statistics of [10] and the supremum statistic of [11]. Another method for detecting change points is introduced in [12]. The authors present a multiple-change-point analysis for which the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampler plays a fundamental role. They propose an attractive methodology for the change-point problem in a Bayesian context. The reversible jump algorithm is presented. Ref. [13] also studies the problem of detecting change points in the mean of a signal corrupted by additive noise. The number of change points is estimated by a method based on a penalized least-square criterion. Ref. [14] uses the minimum description length for detecting change points for a non-stationary time series with an application to GARCH models, stochastic volatility models and generalized state-space models as the parametric model for the segments. Ref. [15] uses maximum likelihood to estimate the instant of the change. The authors study the asymptotic distribution of their test by contiguity. Ref. [16] investigates the regression function or its th derivative in generalized linear models which may have a change (discontinuity) point at an unknown location. Ref. [17] studies change points in the mean of a sequence of independent normally distributed random vectors. The asymptotic distribution of the test statistic is studied by using results from [18]. Also, Ref. [19] studies this problem for independent normal means as a multiple testing problem. The authors consider two stepwise methods, the binary segmentation method of [20] and the maximum residual down method of [21]. They prove the consistency of these methods. Ref. [22] studies the existence of changes in the regression parameters in a linear model where the regressors and errors are weakly dependent. They study the asymptotic distribution under the null hypothesis and under contiguous alternatives. In [23], the authors develop a method for detecting and estimating change points in the tail of multiple time series data. They discuss the effect of the mean and variance’s change on the tails. They focus on the detection of change points in the upper tail of the distribution of the variable of interest, based on multiple cross-sectional time series. Ref. [24] proposes a procedure based on the Bayesian information criterion () in combination with the binary segmentation algorithm to look for changes in the mean, autoregressive coefficients, and variance in the perturbation in piecewise autoregressive processes. The authors explain briefly the Auto-PARM and Auto-SLEX methods. They present different algorithms useful to the search of multiple change points. Ref. [25] proposes a likelihood ratio scan method for estimating multiple change points in piecewise stationary processes. Ref. [26] aims to estimate the instant of change in a regression model. The authors use a sequential Bayesian change-point algorithm that provides uncertainty bounds on both the number and location of the change. A class of change-point test statistics is proposed in [27] that utilizes a weighting and trimming scheme for the cumulative sum (CUSUM) process inspired by Renyi. Using an asymptotic analysis and simulations, the authors demonstrate that this class of statistics possesses superior power compared to traditional change-point statistics based on the CUSUM process, when the change point is near the beginning or end of the sample. The authors develop a generalization of these "Renyi” statistics for testing for changes in the parameters of linear and non-linear regression models, and in the generalized method of moment estimation.

In this paper, we are interest in weak change detection. A weak change is one with a too-small magnitude. Such a change may be a harbinger signaling a forthcoming critical behavior of the phenomenon studied. It can manifest in various domains including economics and finance, public health, bio-science, engineering, climatology, hydrology, linguistics, genomics, signal processing and many others.

Classical change detection methods can fail in detecting weak changes. Therefore, it may be of importance to develop new methods for their detection. In the context of time series, very few studies have tested no change against local alternatives of weak changes. Refs. [4,28] study this problem for the case of testing the mean of the model (1). As changes can happen elsewhere than the mean, it can be interesting to study more general models. Our main purpose in this paper is to extend these works to the conditional mean of (1). With this purpose, we proceed with the same techniques. We first construct a test based on the likelihood ratio, and we study its null distribution. Next, we establish the LAN property for the likelihood families under study. From this, we prove the contiguity of and and use it together with Le Cam’s third lemma to find the asymptotic distribution of the test under . Then, we prove the optimality of our test in the case in which the parameters are known. In the case that the parameters are assumed to be unknown, we prove the convergence of the estimated version of the central sequence based on the parameter estimators to its true version. Finally, we prove that the test remains optimal in the case of unknown parameters. Based on the explicit expression of the power, we construct an algorithm for detecting change points and estimating their locations. The simulation study shows the good performance of our method for detecting weak changes and estimating their locations in the examples considered.

In Section 2, we specify the notation and list some of the main assumptions. In Section 3, we state the theoretical results in the case that is known and in the case that it is unknown. The results of this section are used in Section 4 to construct an algorithm for testing change points and estimating their locations. In Section 5, a simulation experiment is conducted for the application of our algorithm. Section 6 concludes our work, and the last section contains the proofs of the results stated in Section 3.

2. Notation and Assumptions

In this section, we specify the notation and list some of the main assumptions needed.

2.1. The Notation

In the sequence, is the space of real matrices and . is the transpose of , and is its Euclidean matrix norm. is the Euclidean norm of .

Let ; we write and for any ,

For , we write

where for , .

Let be a differentiable function on . For any , we denote by the following matrix:

where is the gradient of ℑ with respect to at :

where for and , is the partial derivative of ℑ with respect to .

We also denote by the matrix

where, for every

We denote any differentiable function g with derivative by

For any , let be the -algebra generated by such that is independent of .

2.2. The Main Assumptions

In this section, we outline the key assumptions needed for our methodology. These are crucial for establishing our theoretical results. Following their enumeration, we include a remark that articulates their significance. So, we assume that

- (A1)

- and .

- (A2)

- f is differentiable with derivative .

- (A3)

- (A4)

- is differentiable with derivative and is -Lipschitz where

- (A5)

- (A6)

- For any , designates the number of observations between the instants and , such that and , as n tends to .

- (A7)

- For all the sequence is stationary and ergodic on with stationary cumulative distribution function .

- (A8)

- For any , and ,

- (A9)

- , for some positive function defined on .

- (A10)

- For .

- (A11)

- The density function of the first d observations on each interval under converges to its density function under .

Remark 1.

- Assumptions (A1)–(A5) are regularity properties required for the density f. They are satisfied at least by the standard Gaussian density function.

- Assumption (A6) allows for the application of the ergodic theorem on each segment . This assumption is very usual in the literature.

- Assumption (A7) ensures the ergodicy and stationarity of the process on each segment . It holds at least for piece-wise stationary and ergodic AR and ARCH models.

- Assumptions (A8)–(A10) are constraints on the function T and its derivatives. They are satisfied by usual models as parametric AR, ARCH, TARCH, and EXPAR models with Gaussian noise.

- Assumption (A11) allows for the simplification of the forms of the likelihoods.

3. The Theoretical Results

3.1. The Parameters Are Known

We first study the case where and are assumed to be known. This will enlighten the case where they are unknown. We start by establishing a LAN and contiguity results.

We denote by the log-likelihood ratio of against , and we define the sequence by

where

and for all

Theorem 1 (LAN).

Assume that (A1)–(A10) hold. Then, for any , under , as ,

with

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

Corollary 1.

Assume that (A1)–(A10) hold. Then, for any , the sequences and are contiguous. Furthermore, under , as ,

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

For known and , and for any , for testing against , we base our test on the statistic

where is any consistent estimator of

At the level of significance of we reject whenever where is a -quantile of the standard Gaussian distribution.

In practice, can be taken as a natural estimator of with and for is an estimator of and

where is the empirical distribution function of the observations with indices in . This can be written again as

Theorem 2 (Optimality).

Assume that (A1)–(A10) hold. Then, for any given ,

- [i]

- Under , as ,

- [ii]

- Under , at the level of significance of , the asymptotic power of the test based on iswhere is the -quantile of a standard Gaussian distribution with cumulative distribution function Φ.

- [iii]

- The test based on is locally asymptotically optimal.

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

3.2. The Parameters Are Unknown

Here, we place ourselves in the framework of Model (1) with unknown. We study the case in which is known and the case in which it is unknown. We previously studied the asymptotic normality of an estimator of under and under . For any and , define

We consider the following additional assumptions:

- ()

- The model is identifiable, that is, for , ,

- ()

- The true parameter has a consistent estimator that satisfies the Bahadur representation (see, e.g., [29]), given bywhere

- .

- For any , such that

- and .

- ()

- For any ,

- ()

- For any and , there exists a ball of radius r, such that

- ()

- For and ,

Remark 2.

- In the literature, one can find numbers of models with functions satisfying () and ().

- Assumption () is useful for the estimation of , while () helps for the study of the distribution of the test statistic. It has been used before in [4]. It is satisfied by least-squares and likelihood type estimators for some usual models within (1).

Recall that, for any under , the central sequence with the true parameter is denoted by and its estimated version by .

Proposition 1.

Under the assumptions (A1)–(A10) and ()–(), we have

- [i]

- Under :

- [ii]

- Under :whereand

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

3.2.1. The Parameter Is Known

As explained in [4], in practice, the case where the parameter is known may be encountered when there is no apparent change, and one wishes to test for possible weak changes. That is the situation where . This is what is usually tested in the literature. Recall that

Note that, by our assumptions, the following real numbers

are finite. Furthermore, since for any depends on and on , which itself depends on (which is unknown) and on , we estimate it by , given by

Despite the fact that we consider any consistent estimators of and , we will take them here to be, respectively,

and

where for all is an estimator of which can be taken to be

Proposition 2.

Under the assumptions (A1)–(A10) and ()–(), for any , we have, for any sequence of positive integers such that as ,

- [i]

- [ii]

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

In order to test against , for any , we consider the following statistic:

Theorem 3 (Optimality).

Assume that (A1)–(A10) and ()–() hold. Then, for any given and for any sequence of positive integers such that, as , we have the following:

- [i]

- Under , as , .

- [ii]

- Under at the level of significance , the asymptotic power of the test based on the statistic is , where is the -quantile of the standard Gaussian distribution with cumulative distribution function Φ.

- [iii]

- The test based on the statistic is locally asymptotically optimal.

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

3.2.2. The Parameter Is Unknown

In practice, is generally unknown and has to be estimated, as well as , where, for any , . Many methods can be used to obtain consistent estimators of these parameters. Let be the maximum likelihood estimator of under and let be the maximum likelihood estimator of under . Then, we easily have that in probability, asymptotically,

The above equality allows for the study of the test statistics in the same lines as in the case where is known.

We need the following assumptions:

- ()

- For any , , forfor some positive function defined on

- ()

- For , and ,

- ()

- .

Let be any sequence of positive integers satisfying as . For testing against , , we use the test based on the statistic

Proposition 3.

Assume that (A1)–(A10), ()–() and ()–() hold. Then, for any sequence of positive integers satisfying as , for any sequence of consistent and asymptotically normal estimators of and for any , we have, under and as ,

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

Theorem 4 (Optimality).

Assume that (A1)–(A10), ()–() and ()–() hold. Then, for any given , we have

- [i]

- Under , as , .

- [ii]

- Under at the level of significance , the asymptotic power of the test based on the statisticis , where is the -quantile of the standard Gaussian distribution with cumulative distribution function Φ.

- [iii]

- The test based on the statistic is locally asymptotically optimal.

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

4. Application to Detection of Change Points and Their Location Estimation

The time series at hand has jumps if the parameters of its distribution change at certain times. The current test, applied to the model (1) adjusted to this time series, for testing the null hypothesis of no change against at least one change, is conducted with a whose components are all equal to, say, , the parameter of the stationary distribution on the first segment .

The test constructed in this work can do more than testing no change against at least one change. To understand this, assume changes have been detected in the data by a given method, and their locations have been estimated. This test can serve as a screening method for finding possible missing changes by this method. In this situation, one can assume the changes already detected as well as their locations as known. With this, all the components of will no longer be the same, and some of the ’s in the model would be considered known. Thus, our test can be used for testing the null hypothesis of changes against at least changes, for some given .

For any , denote by any estimator of the local power of this test at , with the convention that , , the level of significance. Let and , (), the m first stationary observations.

Our procedure for detecting changes in the time series and estimating their locations is described in the following algorithm.

- Location 1:

- (A1): Take any t between 1 and so that there is a large number of indices before and after t (for example ).

- Adjust Model (1) to with a potential change located at the time index t, and apply the testing procedure studied.

- If

- Put and go to Location 2 (first change location estimated)

- Else

- Carry out and go to (A1).

- Location 2:

- Consider the next h observations to :

- Put and conduct the following:

- (A2): Take any t between and so that there is a large number of indices before and after t.

- Adjust Model (1) to with a potential change located at the time index t and apply the testing procedure studied.

- If ,

- Put and go to Location 3 (second change location estimated)

- Else

- Carry out and go to (A2).

- Location i:

- Let be the change location at step i-1

- Put and perform

- (Ai): Take any t between and so that there is a large number of indices before and after t.

- Adjust Model (1) to with a potential change located at the time index t and apply the testing procedure studied

- If ,

- Put , and go to Location i (ith change location estimated)

- Else

- Carry out and go to (Ai).

Note that simple can be obtained by plugging estimators of the parameters into the expressions of the local power given in Theorems 2–4.

5. Simulation Experiment

In this section, the theoretical results are applied to simulated data, using the software R 4.2.0. We first study the power of the test as a function of the magnitude of the breaks when these are given. Next, we use the power for estimating the location of the breaks when they are no more assumed to be fixed. The results we present in the sequel are obtained for the nominal levels . Almost all the estimators in this section are computed from 5000 replications. We use the following particular CHARN model:

where n denotes the number of observations, is a standard white noise with a differentiable density f. Here, on , , , ; and are parameters to be specified in each particular model considered.

5.1. Simulation Methodology

Our methodology for conducting the simulation experiment works as follows. For some given and fixed values of and number of changes k, for , we consider different values of the triplet corresponding to the shift in the parameter on each interval , with (indicating no changes in the first interval). This provides us with observations in the j-th interval. Subsequently, we utilize the model (13) to simulate these observations, to which our algorithm (see Section 4) is then applied.

5.2. Power Study for Given Break Locations

5.2.1. and f Are Known

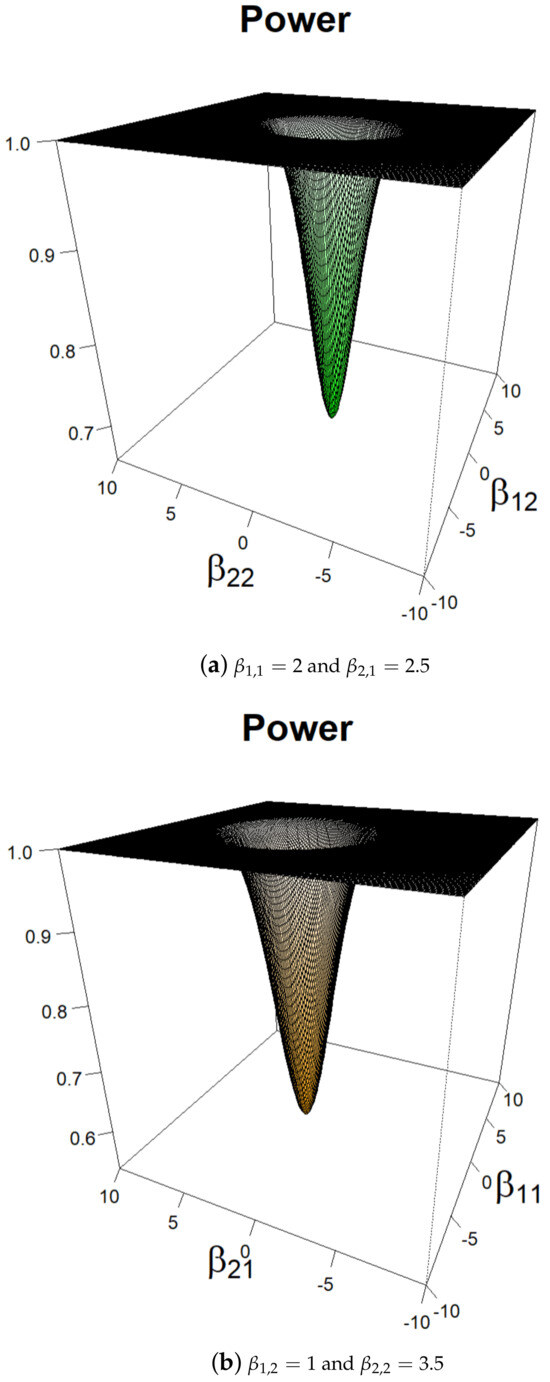

Now, we treat a particular case of (13). We consider , , f is the standard Gaussian density, , , , and for , with , , and . For , to study the behavior of the power as a function of magnitudes of the changes, we fix one component of each and we compute the power of the test as a function of the other components. The results are plotted on Figure 1, where one can observe that the power grows quickly to one as the norm of the magnitude grows.

Figure 1.

Power of the test with respect to in a class of AR(1) models when f is a standard Gaussian density.

5.2.2. and f Are Unknown

As we said before, in practice, and f are unknown and must be estimated. While we estimated by the least-squares method, we estimate f by the Parzen–Rosenbatt estimator (see [30]), defined by

where

where and denote the least-squares estimators of and , respectively, is the smoothing parameter, and K the kernel symmetric function having the following properties:

- 1.

- for any (positivity).

- 2.

- (density).

- 3.

- (by symmetry).

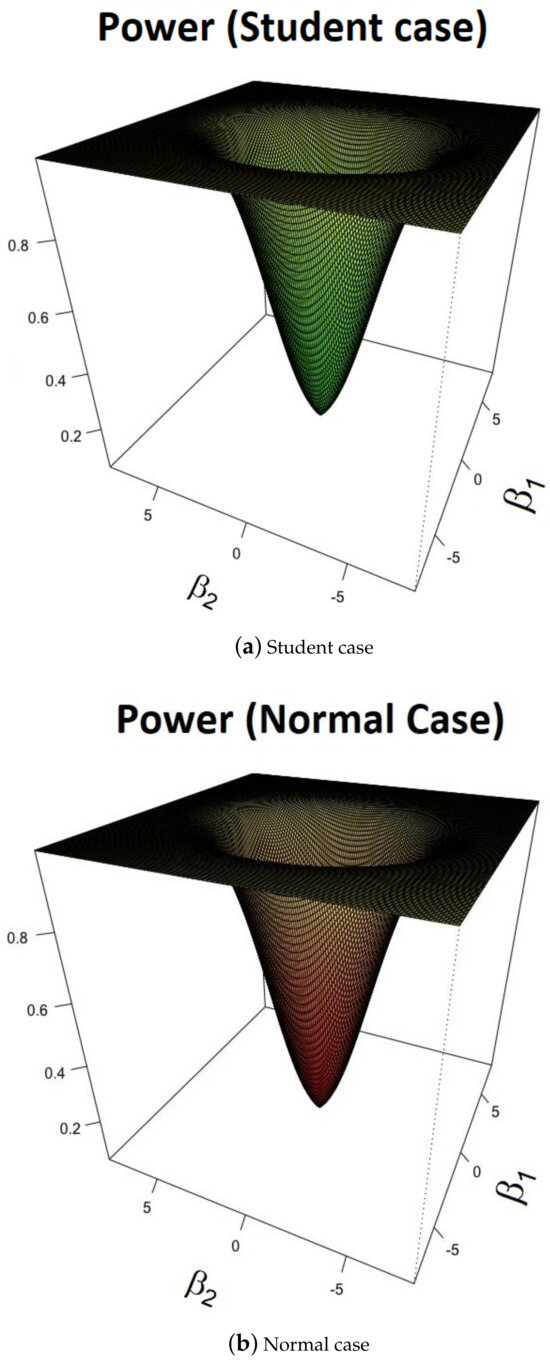

Now, we calculate the power of the test using these estimators. We choose a Gaussian kernel K and , with being the sample standard deviation. We consider a sample of observations, and we generate the observations from (13). The results for and at the level of significance are given in Figure 2. It is clear that the local power of the test has approximately the same behavior for the standard Gaussian and the standard Student densities. The results do not change significantly for Epanechnikov, uniform kernel, quadratic kernel, etc.

Figure 2.

Power of the test with respect to in a class of AR(1) model when f is the kernel estimated.

5.3. Detection of Change Points and Estimation of Their Locations

In this subsection, we detect change points and we estimate their locations in simulated data. Ref. [4] studied the case of changes only in . We start by evaluating the power of the test in case of no break in the data. Next, we study changes in . Finally, we study changes in and simultaneously.

5.3.1. No Break

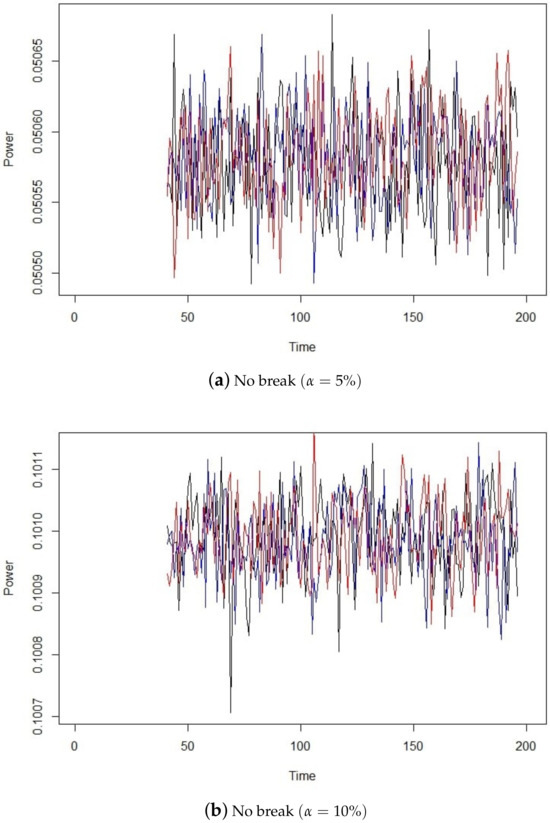

Following the algorithm in Section 4, we start by calculating the asymptotic local power given by (7) in the case where there is no break, that is, for . We consider a sample of observations generated from Model (13), for and f, a standard Gaussian density.

For and , the asymptotic local power of our test with different levels of significance is plotted on Figure 3. We can see there that the local power does not exceed when and does not exceed when . Then, for any or , for the thresholds corresponding to and , respectively, we keep the null hypothesis and conclude that there is no break in the data.

Figure 3.

No break in the data.

5.3.2. Case of One Single Break

Here, we consider the problem of detecting one single break when it happens jointly in and . For and , for different values of and ; the estimation of the break location, as well as the root mean square error (RMSE), is presented in Table 1. One can see from this table that the estimation is accurate and that the RMSE is large for smaller .

Table 1.

Break location in an AR(1) model with the corresponding RMSE.

5.4. Case of Three Breaks ()

Now, we study the case of three breaks when piece-wise models AR(1) and AR(1)-ARCH(1) are adjusted to the data. Note that these models are sub-classes of CHARN(1,1) models.

5.4.1. AR(1) Models

We start with AR(1) models. For the data are obtained from (13); for , , , , and is a sequence of standard Gaussian white noise. The number of change points is assumed to be unknown, and we aim to detect them and estimate their locations using our theoretical results and following our algorithm. For 5000 replications, , for different values of the magnitude of change , and for the same threshold , the estimations obtained are displayed in Table 2 together with their associated RMSE (in brackets). These results seem to show that our method tends to estimate the correct number of changes but overestimates their locations with a relatively large RMSE when the jumps in the parameters of the AR(1) models are too small. Again for an AR(1) model, for , we fix , and the instants of breaks , and we monitor the corresponding break estimates with respect to the variation in the threshold corresponding to different . For , our method overestimates the number of changes (six instants detected). For and , it estimates the correct number of changes but overestimates their locations. For , it underestimates the number of changes and overestimates their locations. The overestimation of the break locations may be explained by the weakness of the magnitude of changes. If we consider the same study for , we obtain the same results for the number of changes, but with more accurate change location estimations.

Table 2.

Break location estimation in a class of AR(1) models for a fixed .

5.4.2. AR(1)-ARCH(1) Models

Here, we consider Model (13) for , , , and , , which leads to an AR(1)-ARCH(1) model. For Table 3 shows the estimation of change locations corresponding to the same and different magnitudes of change. We can see that our method estimates the correct number of changes but overestimates their locations with a relatively large RMSE.

Table 3.

Break location estimation in AR-ARCH models.

5.4.3. Conclusions

Based on the previous simulation results, we can conclude that our method is sensitive to the choice of , and is efficient in detecting weak changes and estimating their locations in an AR(1)-ARCH(1) model we have considered when the magnitudes of the changes are not too small.

5.5. Comparison with [27]

In a class of shifted models, Ref. [28] performed a comparison between her method, which is a different case from ours, and other methods including the one of [27]. She concluded that her method is more efficient for estimating weak break locations.

In this section, we compare our method to that of [27], denoted by SCUSUM, for a class of more general models. Recalling Model (13), we consider many cases of one single break corresponding to different instants , and we take and . For , and different values of we perform 1000 replications, and at each replication, the change location is estimated by SCUSUM and by our method. Table 4 shows the results obtained.

Table 4.

Break location estimation obtained by our method and SCUSUM for different instants of break and different magnitudes of change.

For most of the 1000 replications, SCUSUM was not able to detect any change. For that reason, we kept only the cases where it detected a change, and we calculatec the mean of the change locations estimated. The results are displayed in Table 4, from which it is obvious that our method is more accurate than SCUSUM for the detection of weak changes in the parameters of the AR(1) model studied.

5.6. Application to Real Data

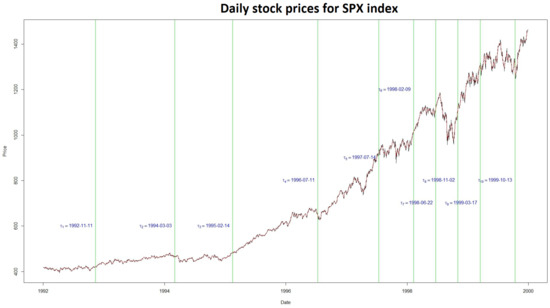

Here, we applied our methodology to detecting changes in the log S&P stock price data obtained from the website https://finance.yahoo.com/quote/, accessed on 1 May 2024. These daily data cover the period from January 1992 to December 2000 and represent one of the most closely followed stock market indices worldwide, serving as a significant indicator of the U.S. economy. The raw data exhibit a trend, which shows that the S&P 500 index is non-stationary (see Figure 4). With this, our methodology can not be directly applied to this series.

Figure 4.

Estimated change points in the S&P 500 indices.

Let denote the S&P 500 stock price index on day t, and define as

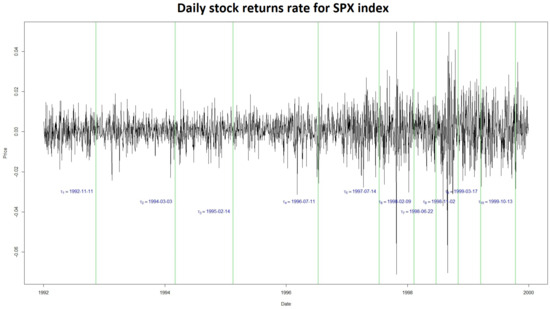

The function log being monotonic implies that the change-point locations in , , and are identical. Graphically (refer to Figure 5), appears to be approximately piece-wise stationary over a finite number of segments, which aligns with the requirements for applying our methodology to study changes in the raw data.

Figure 5.

Estimated change points in the residual series of S&P 500 indices.

To accommodate these characteristics, we adjust the CHARN model within each segment , where . The Gaussian assumption is validated by applying the Shapiro–Wilk test.

Then, applying our procedure to this model, we obtained the following break location dates: 1992-11-11, 1994-03-03, 1995-02-14, 1996-07-11, 1997-07-14, 1998-02-09, 1998-06-22, 1998-11-02, 1999-03-17, and 1999-10-13. The changes occurring in 1992 can be linked to the damage caused by the hurricane Andrew or by the Europian Monetary System crisis. The one in 1994 can be associated with the U.S. lifting of the trade embargo on Vietnam. Those in 1995 can be due to the bankruptcy of the Barings bank. That in 1997 may be associated with the Asian crisis. Those in 1998 may be connected to the rescue organized by the New York Federal Reverve Bank. Finally, those of 1999 can be associated with the cancellation of the 1933 Glass–Steagall Act by the so-called Grammi–Leachi–Bliley Act.

6. Conclusions

We generalized the work of [4] to a class of more general CHARN models. We studied weak breaks in the parameters of the function T when the function V and the parameters and are known. We established a LAN and contiguity results. We given an explicit expression of the local power of the test.

Next, we studied the case where is unknown and is known or unknown. We estimated these parameters, and proved the convergence of the central sequence based on the estimated parameters to the one based on the true parameters. In this case, we proved that the test remains optimal if we replace the parameters with their estimators. From these results, we used the theoretical power for detecting weak breaks and estimating their locations in time series through an algorithm that we constructed.

The simulation experiment conducted shows that our method can detect weak breaks in the parameters of the linear AR(1) and the non-linear AR(1)-ARCH(1) models considered. Also, the location of the breaks as well as their number can be accurately estimated when the magnitudes are not too small.

Compared to [27], it seems to be more efficient for estimating weak break locations. Sometimes, the method in [27] detects breaks in data simulated with no break. This did not happen with our method when we chose a suitable . Our method was also applied to a set of financial data.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Y.S. and J.N.-W.; Software, Y.S.; Validation, J.N.-W. and Z.K.; Investigation, Y.S.; Writing—original draft, Y.S., J.N.-W. and Z.K.; Writing—review & editing, J.N.-W.; Visualization, Z.K.; Supervision, J.N.-W. and Z.K.; Project administration, J.N.-W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Appendix A. Proofs

This section provides the proofs of the results stated in the preceding sections.

Appendix A.1. Proof of Theorem 1

For any , the log-likelihood ratio of against is given by

First, we show that as , decomposes into

where

and

- and for ,

- where is a null matrix and for any

- where, for ,

Applying a first-order Taylor expansion on in a neighborhood of , we obtain, for some lying between and ,

To simplify the study, we calculate all the expressions we need.

Then,

Now,

where, observing that for any t and for any ,

with standing for a null matrix and

with

Let

Using (A3), we have , and . Now, using (A4) and the ergodic theorem, from a simple calculation, we can prove that

It results from above that

where and are defined by (A2) and (A3), respectively.

Now, we study of the asymptotic behavior of under .

By the piecewise stationarity and ergodicity, for any , we can write, almost surely,

with

Thus, we can write

Now, we prove that under ,

We consider the sequence

and we define for every

We use Corollary 3.1 of [31] to study the asymptotic behavior of .

It is easy to prove that is a martingale sequence.

Using the fact that is independent of for and using the ergodic theorem, we can show that, almost surely,

which shows that the first condition of Corollary 3.1 of [31] is verified. It remains to check the Linderberg condition. Let ; by the Hölder inequality, using Markov inequality and the ergodic theorem, we can write that as ,

Then, the conditions of Corollary 3.1 of [31] are completely verified, so that under , we have

Consequently, under , we have

Collecting the above results, the LAN property is established with the central sequence .

Appendix A.2. Proof of Corollary 1

For any , from Theorem 1, under , as

It results that, under , as ,

Then, it is easy to see that under as ,

where .

Since and

under , we have

Using [32] or [33], we obtain that the sequences and are contiguous, and that under , as ,

Appendix A.3. Proof of Theorem 2

From Theorem 1 and Corollary 1, we can conclude immediately that, under , as ,

Part [i] is a direct consequence of Theorem 2 and is briefly explained in the proof of Corollary 1.

As explained there, the sequences of hypotheses are contiguous, and under , as , we have

By (A6) and the Le Cam’s third lemma (Proposition 4.2 in [32]), under , as ,

We recall that, under , as ,

where

This convergence remains true under by contiguity. From Theorem 2, it can be seen that, as , under ,

Thus, by the Le Cam’s third lemma, we can conclude that under , as ,

Indeed, for , we can write

From which it results that, under and as ,

For parts [ii] and [iii], to calculate the asymptotic power of our test statistic, we calculate the asymptotic cumulative distribution of under . We have

where is the cumulative distribution function of a standard Gaussian law with its -quantile.

By Section 4.4.3 of [33], the test based on is locally asymptotically optimal.

Appendix A.4. Proof of Proposition 1

Appendix A.4.1. Proof of [i]

From the Bahadur representation (9), as in [34,35], we consider the following sequence:

and

It is easy to see that is centered for every . Since for any , from a simple calculation, we prove that is a martingale sequence.

We check now the first condition of Corollary 3.1 of [31]. Since is independent of for we can write

By the assumptions (), () and the ergodic theorem, for , we can write

Then,

Finally, we check the Linderberg condition, that is, the second condition of Corollary 3.1 of [31]. In this purpose, we prove that, as n ,

Let . By the Hölder inequality, and Markov inequalities, we can write

By the piece-wise stationarity and the ergodic theorem, for , we obtain almost surely that

Then, using Corollary 3.1 of [31], we conclude that, under , we have

which implies that, under and as ,

where is the covariance matrix defined as

Appendix A.4.2. Proof of [ii]

We recall that under , as ,

where

with

We consider the sequence . By Le Cam’s third lemma, under , as ,

where

Since , , is independent of , , and using the stationarity and the ergodic theorem, we can easily see that

where

Then, under , we have

From this result and Le Cam’s third lemma, under , as n tends to , we have

Appendix A.5. Proof of Proposition 2

Appendix A.5.1. Proof of [i]

We prove the convergence of the central sequence (4) to its estimated version in order to verify that the test still be optimal when we replace the parameter by its estimator. For any and , we define

Then the log-likelihood ratio of against is . For lying between and , we write a second-order Taylor expansion of around and obtain

We wish to prove that, under , as ,

In order to simplify the notations, let .

By a multiple use of a Taylor expansion, by the assumptions (), (A9), by the ergodic theorem, from a simple calculation, we prove that, for , is bounded.

Thus, as , tends in probability to a finite positive real number, denoted by b.

Recall from (A11) that, as we have

Since under , as , we have

it results that

From (A12), we can write

Now, we prove that

Adding and subtracting appropriate terms, as , we can write

where stands for a sequence of positive integers such that as

Observing that, as ,

it is easy to see that,

Then, it suffices to show that converges in probability to a random vector. For this, we can write the following decomposition:

Using the assumptions () and (A5), and the ergodic theorem, since is independent of , the study of the asymptotic behavior of and shows that, as ,

Thus, tends in probability to a finite positive real number. Consequently,

It results that

Hence,

In order to treat the above equation (A14), we need the following lemma.

Lemma A1.

Assume that () holds. Let be a sequence of positive integers such that tends to 0 as . For , is asymptotically in the tangent space to the curve of at , defined as follows:

Proof.

Writing a second-order Taylor expansion of in a neighborhood of , for some lying between and , we obtain

To prove that, as , belongs to , it suffices to show that

To find the asymptotic distribution of , we add and substract appropriate terms and we obtain

Then, asymptotically, has the same distribution as . This means that converges in distribution to a normal law.

Now, to prove that , it suffices to show that the sequence converges in probability to a random vector.

Recall that

where stands for a sequence of positive integers such that as , is given by (), and lies between and .

We have, as , then,

For some lying between and , we proved previously that converges in probability, as , to a finite positive number. By following the same lines, we can prove that converges in probability to a positive finite number, where lies between and . Consequently,

□

It results from Lemma A1 that, as belongs to the tangent space . Thus, by replacing z by , we obtain

Finally, recalling (A14), we obtain

Appendix A.5.2. Proof of [ii]

To prove (12), it suffices to show that, as , . For any , we have

We add and substract appropriate terms and we obtain

where, for

For all , we have

For and , using the assumption (A9) and the fact that the functions are bounded, it follows from the Lebesgue’s convergence theorem that each term in the right-hand side of (A15) tends to 0.

Appendix A.6. Proof of Theorem 3

Appendix A.6.1. Proof of [i]

The statistic that we study is

We proved in Proposition (2) that

Also, we proved that, as ,

Then, under and as , we have

and

Appendix A.6.2. Proof of [ii] and [iii]

The convergence of to remains true under the local alternatives by contiguity. Then, under and as , using Le Cam’s third lemma, we have

which shows that the power of the test remains the same.

Appendix A.7. Proof of Proposition 3

The proof relies on a number of lemmas that we state and prove.

Lemma A2.

Assume that (A1)–(A10), ()–() and ()–() hold. Then, for any sequence of positive integers satisfying, as , , for any sequence of consistent and asymptotically normal estimators of and for any , under and as ,

Proof.

Starting with (A17), by multiplying and dividing by , we observe that

For , an estimator of , by following the same techniques as in Proposition 1, under , as , converges in distribution to a normal distribution and tends to 0 in probability as .

For any and , for the maximum likelihood estimator of , we write a first-order Taylor expansion of in a neighborhood of and we obtain, for some lying between and ,

where

Our aim is to prove that, under , as ,

Then, to prove (A17), it suffices to show that tends in probability, as , to some positive random variable. Recalling (4), we have

Then,

and

where, for any is the Hessian matrix of with respect to .

Recall that we wish to bound . For any , we have

By assumptions (), (A9), (A4) and (A5), using multiple Taylor expansion and the ergodic theorem, since is independent of , the study of the asymptotic behavior of shows that

Then, for , we proved that converges to a finite positive number. From this, we find that converges to a finite positive number.

For proving (A17), one can write

Using Proposition 1, we can see that, under , converges to a finite positive number. Since tends to in probability, and converges under to some finite positive number, it follows that

Now, we prove that

By adding and subtracting appropriate terms, we obtain

where stands for a sequence of positive integers such that as

Observing that, as ,

it is easy to see that,

By assumptions (), (A9), () and (A5), using a suitable application of the ergodic theorem, since is independent of , we can show that

Thus,

□

To treat the above equation, we need the following lemma.

Lemma A3.

Let be a consistent and asymptotically normal estimator of Let be a sequence of positive integers such that tends to 0 as For and , is asymptotically in the tangent space to the curve at , defined as follows:

Proof.

Writing a second-order Taylor expansion of in a neighborhood of , for some lying between and , we obtain

To prove that, as belongs to , it suffices to show that

Then, we study the asymptotic distribution of . By adding and subtracting appropriate terms, we obtain

It is easy to see that, as , has the same distribution as and then, converges in distribution to a normal random vector.

To prove that , it suffices to show that converges in probability to a random vector.

Now, we write

where stands for a sequence of positive integers satisfying as , is an asymptotically normal estimator of and lies between and .

Previously, we proved that converges in probability to a positive random variable where lies between and . Following the same techniques, we can prove that the sequence converges in probability to a positive random variable, where lies between and .

It results that

It follows from Lemma A3 that, as , belongs to the tangent space . Replacing y by , we obtain

Recalling (A20), we obtain

□

Now we need the following lemma.

Lemma A4.

Assume that (A1)–(A10), ()–() and ()–() hold. Let be a sequence of consistent and asymptotically normal estimators of . Let be any sequence of positive integers such that as . Then, for any , under , as , we have

Proof.

Following the same techniques as above and by applying Taylor expansion of in a neighborhood of , for some lying between and , we obtain

We have

Recall that, under , converges to a finite Gaussian random vector and, almost surely, as , tends to . We study the convergence of .

Based on the proof of Lemma A2, we have

Based on the assumptions ()–() and ()–() and using the same techniques, we can prove that converges to a finite positive number. Thus, converges almost surely to a finite random positive number.

From these results, we can conclude that

Then, we can write

Adding and subtracting appropriate terms, we obtain

By the assumptions ()–() and by the ergodic theorem, we can prove that

where is a sequence of positive integers such that, as , Returning to the proof of Proposition 3, and using Lemma A2, we have

We can write

From Proposition 2, we have

and

Finally, using the above results, we can write

Appendix A.8. Proof of Theorem 4

Appendix A.8.1. Proof of [i]

The test statistic is

We proved in Proposition 3 that

We also proved that, as ,

Thus, under , as , we have

and

Appendix A.8.2. Proof of [ii] and [iii]

The convergence of to remains true under the local alternative by contiguity. Then, under and as , using Le Cam’s third lemma, we have

Then, we can say that the power of the test remains the same.

For more proof details, see [36].

References

- Härdle, W.; Tsybakov, A.; Yang, L. Nonparametric vector autoregression. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 1998, 68, 221–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Gan, M.; Chen, G. Generalized exponential autoregressive models for nonlinear time series: Stationarity, estimation and applications. Inf. Sci. 2018, 438, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, Y.C.; Zhao, Z. The asymptotic behavior of the likelihood ratio statistic for testing a shift in mean in a sequence of independent normal variates. J. R. Statist. Soc. 2016, 48, 895–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngatchou-Wandji, J.; Ltaifa, M. Detecting weak changes in the mean of a class of nonlinear heteroscedastic models. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2023, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csörgő, M.; Horváth, L.; Szyszkowicz, B. Integral tests for suprema of kiefer processes with application. Stat. Risk Model. 1997, 15, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNeill, I.B. Tests for change of parameter at unknown times and distributions of some related functionals on brownian motion. Ann. Stat. 1974, 2, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernoff, H.; Zacks, S. Estimating the current mean of a normal distribution which is subjected to changes in time. Ann. Math. Stat. 1964, 35, 999–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.A.; Huang, D.; Yao, Y.-C. Testing for a change in the parameter values and order of an autoregressive model. Ann. Stat. 1995, 23, 282–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelsang, T.J. Wald-type tests for detecting breaks in the trend function of a dynamic time series. Econom. Theory 1997, 13, 818–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, D.W.; Ploberger, W. Optimal tests when a nuisance parameter is present only under the alternative. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1994, 62, 1383–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, D.W. Tests for parameter instability and structural change with unknown change point. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1993, 61, 821–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavielle, M.; Lebarbier, E. An application of MCMC methods for the multiple change-points problem. Signal Process. 2001, 81, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebarbier, É. Detecting multiple change-points in the mean of Gaussian process by model selection. Signal Process. 2005, 85, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.A.; Lee, T.C.; Rodriguez-Yam, G.A. Break detection for a class of nonlinear time series models. J. Time Ser. Anal. 2008, 29, 834–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulos, S.B.; Jandhyala, V.K.; Tan, L. Asymptotic study of the change-point mle in multivariate gaussian families under contiguous alternatives. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2009, 139, 1190–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, J. Detection of a change point based on local-likelihood. J. Multivar. Anal. 2010, 101, 1681–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarušková, D. Asymptotic behaviour of a test statistic for detection of change in mean of vectors. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2010, 140, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piterbarg, V.I. High Derivations for Multidimensional Stationary Gaussian Process with Independent Components. In Stability Problems for Stochastic Models; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 1994; pp. 197–210. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Cohen, A.; Sackrowitz, H. Consistent multiple testing for change points. J. Multivar. Anal. 2011, 102, 1339–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vostrikova, L.Y. Detecting “disorder” in multidimensional random processes. In Doklady Akademii Nauk; Russian Academy of Sciences: Moscow, Russia, 1981; Volume 259, pp. 270–274. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A.; Sackrowitz, H.B.; Xu, M. A new multiple testing method in the dependent case. Ann. Stat. 2009, 37, 1518–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prášková, Z.; Chochola, O. M-procedures for detection of a change under weak dependence. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2014, 149, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, D.; Sun, Y.; Wang, H.J. Detecting Change-Points in Extremes; International Press of Boston: Boston, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Badagián, A.L.; Kaiser, R.; Peña, D. Time series segmentation procedures to detect, locate and estimate change-points. In Empirical Economic and Financial Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Yau, C.Y.; Zhao, Z. Inference for multiple change points in time series via likelihood ratio scan statistics. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. (Stat. Methodol.) 2016, 78, 895–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, E.; Antonellis, M. An exact approach to bayesian sequential change-point detection. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2016, 97, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, L.; Miller, C.; Rice, G. A new class of change point test statistics of Rényi type. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2020, 38, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ltaifa, M. Tests Optimaux pour Détecter les Signaux Faibles dans les Séries Chronologiques. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Lorraine, Nancy, France, Université de Sousse, Sousse, Tunisia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bahadur, R.R.; Rao, R.R. On deviations of the sample mean. Ann. Math. Stat. 1960, 31, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parzen, E. On estimation of a probability density function and mode. Ann. Math. Stat. 1962, 33, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, P.; Heyde, C.C. Martingale Limit Theory and Its Application; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Le Cam, L. The central limit theorem around 1935. Stat. Sci. 1986, 1, 78–91. [Google Scholar]

- Droesbeke and Fine, J.-J. Inférence Non Paramétrique: Les Statistiques de Rangs; Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles: Bruxelles, Belgium; Éditions Ellipses: Paris, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ngatchou-Wandji, J. Estimation in a class of nonlinear heteroscedastic time series models. Electron. J. Stat. 2008, 2, 40–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngatchou-Wandji, J. Checking nonlinear heteroscedastic time series models. J. Stat. Plan. Inference 2005, 133, 33–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, Y. Testing a Class of Time-Varying Coefficients CHARN Models with Application to Change-Point Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Lorraine University, Nancy, France, Lebanese University, Beirut, Lebanese, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).