Semantic and Morphosyntactic Differences among Nouns: A Template-Based and Modular Cognitive Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- (a) CN from PNIn Riffian: a-ʒeħːa ‘mischievous person’, from ʒeħːa ‘Jehha’In English: the-diesel, from Diesel(b) PN from CNIn Riffian: a-zˤʁaɾ ‘Azghar (toponym)’, from a-zˤʁaɾ ‘plain/flat land’In French: la-manche ‘The English Channel (toponym)’, from la-manche ‘sleeve’

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Foundation

2.1. The Nouns and Cognition: A Review

2.1.1. Morphosyntactic Irregularities

2.1.2. Theories of Morphology

The Item and Template Approach

The Lexical Approach and the Definite Article

2.2. Theoretical Proposal

- —

- Computative lexicon: the lexicon has a cognitive generative device comparable with the syntax component.

- —

- Modularity of systems: the templates form a system, which is itself part of the morphological system, and they are independent of each other (i.e., elements of a set).

- —

- The Item and Template approach: items are paired with templates that include grammatical meanings.

- —

- Mathematical mapping: the pairing of linguistic facts is carried out by mathematical relations as defined in Set theory.

- —

- Integration of word formation with the template: lexical derivation contributes to template shift by attributing a different template to an item.

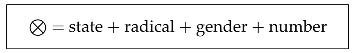

2.2.1. A Mentalistic Algorithm of Lexical Derivation

- (2)

- (a) With the vowel: ða-ɾeʃːint ‘an orange’ from ɾeʃːin ‘oranges’;(b) Without the vowel: t-bujːut ‘a bun’ from bujːu ‘bun’.

2.2.2. Mathematical Foundations of the Cognitive Model

- Let L be the set of the languages;

- Let W be the set of the morphemes or items with ;

- Let M be the set of the meanings;

- Let G be the set of grammatical meanings with ;

- Let indicate the set {¬g | g , that is, ∀ ¬g, a negative element of is defined as an element assigned to the empty set of W;

- Let Γ be a set composed of binary grammatical features such that . We can write +g1, −g1, +g2, −g2, …, +gn, −gn with +gj, −gj, and ∀.

- Let S be a set of syntactic categories;

- Let P be a set of grammatical paradigms generated by the power–set function and . Let Φ be a family of subsets of a set P;

- Let and =. The function e holds if only if it satisfies the conditions as follows:

- (a)

- If , its cardinality is equal to a defined number: , such that is a set consisting of a sequence of integer numbers and, depending on the set S, a function maps S into K.

- (b)

- If ∃ subsets , , such that and , then their properties include that the absolute value of , are improper subsets of each other: , and their symmetric difference is an empty set: .

- Hence, let T be a family of subsets corresponding to the templates such that: .

- Let V be the set of processes of word and meaning formation;

- Let K be an unordered set defined as the set of the retrospective determinants of shifting template such that and the empty subset ∅ is also a subset of K;

- Let be the backward recursive function that maps an item to a subset of K, that is, each subset includes the antecedent shifting factors of an item, and let be the gradient function that maps an element of K to the output template. Hence, let be the morphosyntactic transfer function defined by the composition function that maps an item to an output template, such that :

- Let be an exhaustive disjoint collection of subsets, such as , and , then, , and ;

- Let be a subset: };

- Hence, let the cognitive set be .

2.3. Riffian Nominal Morphology: Traditional Theoretical Background

- (3)

- mana u-miʁis-a u-ħenʒiɾ ([63], p. 283)What AS-clever-this AS-teenager‘What a clever teenager!’

- (4)

- a-ħaɾmuʃ-a ð w-{}-ɾgaz-aboy-this and w-{}-man-this‘This boy and this man’

- (5)

- a-ħaɾmuʃ-a ð-{}-a-ɾgazboy-this ð-{}-a-man‘This boy is a man’

3. Data and Analysis of Empirical Observations

3.1. Preamble

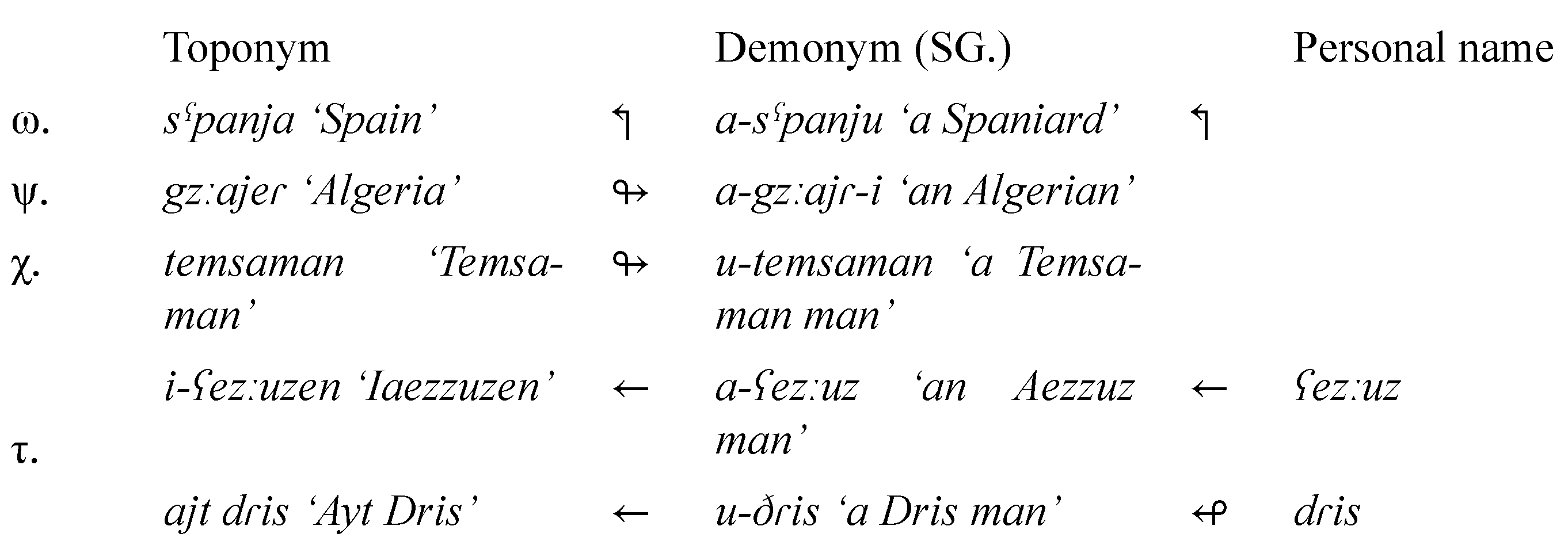

3.2. Countability and Proper Nouns

Application of the Formal Model to PN in Relation to CN

3.3. Countability and Common Nouns

3.3.1. Countability and Loanwords

| Riffanised | Non-Riffanised | |

|---|---|---|

| Uncountable | stateless + feminine marking (e.g., ɾfahmeθ ‘understanding.F.SG’) | stateless + inflectionless (e.g., ɾqahwa ‘coffee.F’) |

| Countable | state + all declensions (e.g., a-mkan ‘place.M.SG’/i-mukan ‘place.M.PL’) | stateless + inflectionless (e.g., ɾmaʕna ‘meaning.F.SG’/ɾemʕani ‘meaning.F.PL’) |

3.3.2. Countability and V-State

| Countable | SG | PL | State SG | State PL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I (seksu ‘couscous’) | − | + | − | − | N/A |

| Type IIa (a-ʃefːaj ‘milk’) | − | + | + | + | + |

| Type IIb (ði-mekɾaðˤ ‘scissors’) | − | − | + | N/A | + |

| Type IIc (a-ʁi ‘whey’) | − | + | − | + | N/A |

| Type IIIa (ʃaɾ ‘soil’) | − | + | + | ± | + |

| Type IIIb (t-fujθ ‘sun’) | − | + | − | ± | N/A |

| Type IV (fus ‘hand’) | + | + | + | ± | + |

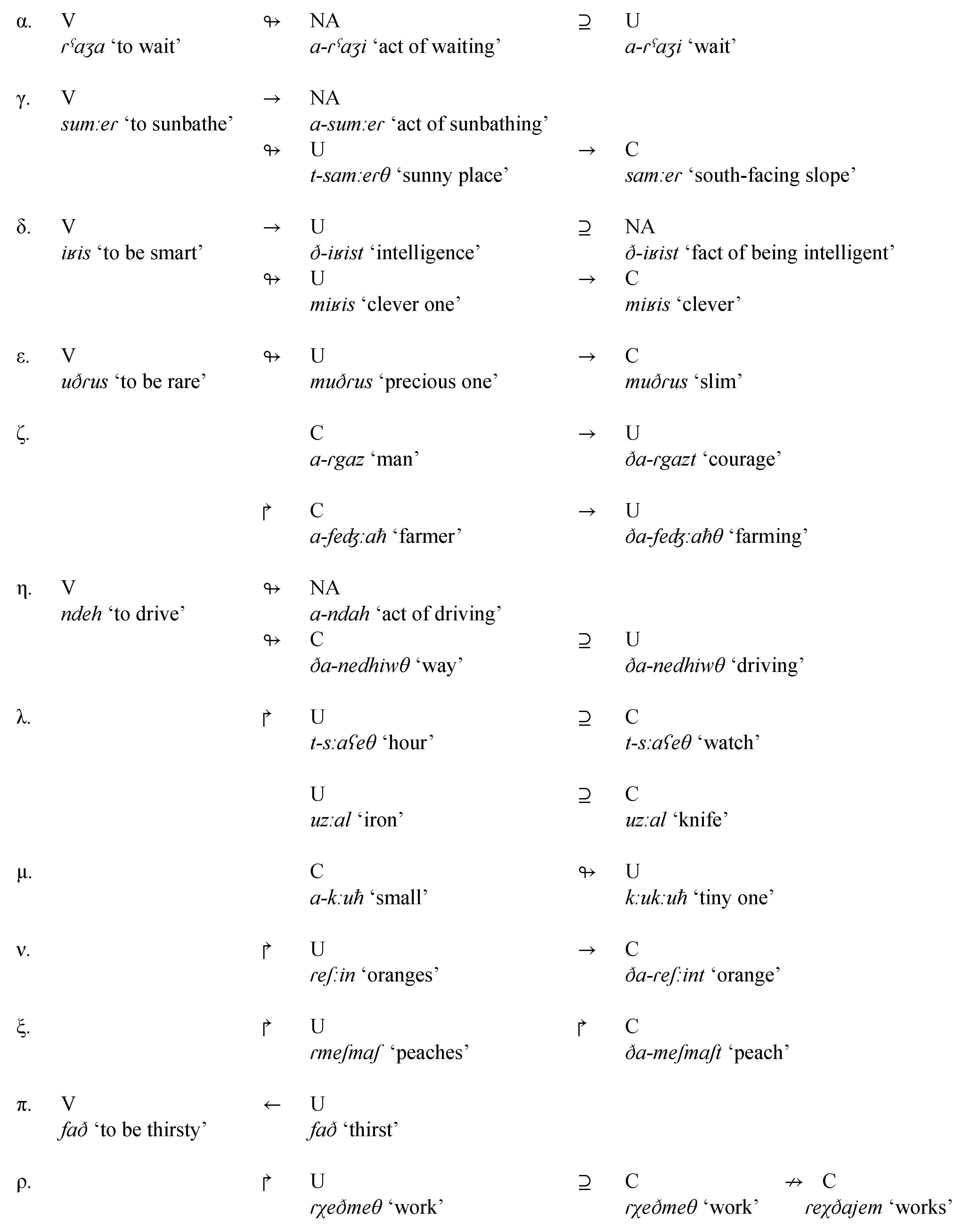

3.3.3. Application of the Formal Model to U in Relation to Other Lexical Categories

- (6)

- V: mzˤi ‘be small’ →U: ðe-mzˤi ‘youth’ ⊇NA: ðe-mzˤi ‘fact of being young’↬C: a-mezˤjan/i-mezˤjanen ‘small.SG/small.PL’

4. Discussion and Properties of the TBMC Model

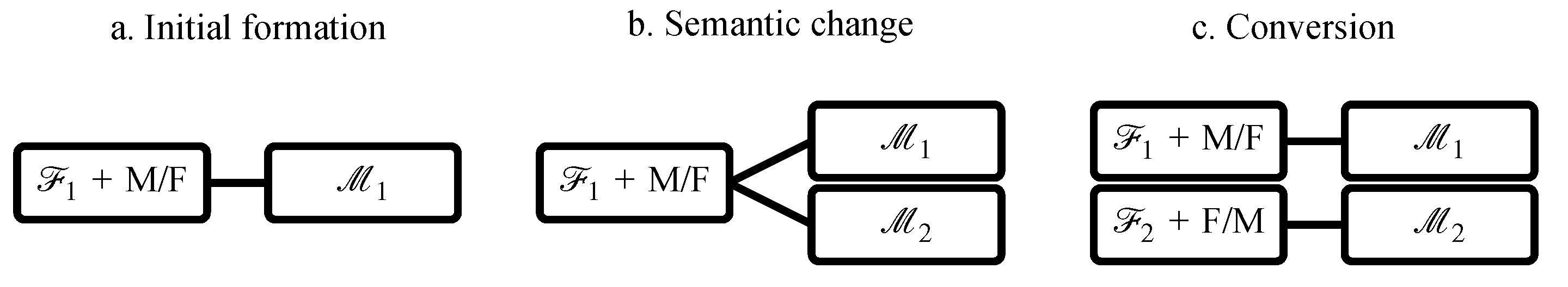

4.1. Semantic Widening Versus Conversion and the Overt Anti-Morphosyntactic Shift

4.2. Gender Shift

4.3. Diachronic Considerations and Immutability

- Consider the following retraction mapping (or lexical loss function) , such as Ω is the set of items of the posterior state and W is the one of the anterior state. Thus, r is a surjective map, such as every ʊ has one and only one pre-image .

- Therefore, there exists an injective mapping , such as and . Hence, ∀ ʊ, ʊ)= ʊ and ʊ ʊ.

- Let the 2-tuples = and = be two instances of the TBMC model representing, respectively, the anterior and posterior states, such as and .

- There exist the homomorphism mappings → and →, such as ∀ ʊ , ʊ=ʊ and ʊʊ).

- Therefore, ∀ ʊ , we have ʊ, ʊ, and, hence, ʊ)=ʊ). Thus, the homomorphic map preserves, in case of lexical loss, the relation as well as the relations and 40.

4.4. The Noun of Address, Morphophonological Avoidance and Linguistic Irreversibility

| Lexical Derivation | Covert Meanings | Overt Meanings | Morphophonological Avoidance | Morphophonological Cloning | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PN | Deverbal N-of-A | V ↬ N | N/A | COL, F or M | − | |

| Onymised CN | NP → N | SING or COL, F or M | COL, F or M | + | ||

| Onymised VP | VP → N | N/A | COL, F or M | + | + | |

| CN | Deverbal U | V ↬ N | N/A | COL, F | − | − |

- If there exist and = such that ⊂ .

- If there exists = such that and belonging to the same syntactic category (see Property 3).

- Then there also exists ⊂ .

4.5. Towards an Alternative Theory: The Countability Paradigm and the Morphosyntactic Encoding

| Singular | Plural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feminine | Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | |

| Uncountable/Collective | t- | (w/j)- | N/A | N/A |

| Countable/Singulative | t-a | a | t-i | i |

5. Cross-Linguistic Perspective and Model Validation

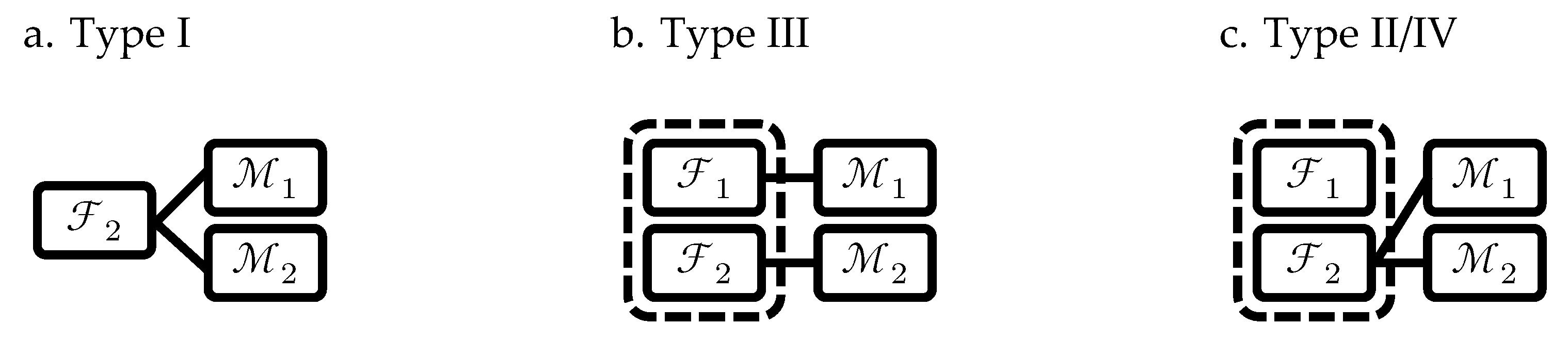

- There exist and forming a pair with morphological templates, such as =, = and .

- There exist and belonging to two different linguistic categories, such as , , , and both are related to the same syntactic category , such as and .

- Let the set correspond to the attributes in and that must be identical, such as is a binary grammatical feature and ⊄Δ

- There holds that −= 0, such that the set contains at least one element.

6. Conclusions

- —

- Unmarked modular template: the template set can encode several templates imposing the grammatical forms that the words must contain.

- —

- Modular cognitive set: the items are assigned to cognitive sets that regulate the pairing of items and templates.

- —

- Formedness: a marker can be formed or unformed (no phonological representation).

- —

- Semiotic encoding: a meaning can be fusional, i.e., it shares a form with another meaning or can be analytic, i.e., it is bound to a different form.

- —

- Prototypical process chain of template shifts: the establishment of such a model clarifies and defines the unmarked form of each modular category without paradox.

- —

- Template shift: depending on gradient conditions, a template shift occurs when passing from one cognitive set into another one.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This paper delves into the intersection of theoretical linguistics and mathematics. Hence, for a better understanding of the notions expressed by the author, we invite readers unfamiliar with some strands of linguistic terminologies to consult these dictionaries, [1,2], covering all the discipline-specific terms used. When it was required for the purpose of scientific clarity, new conceptual terms were coined; we chose to stipulate their definition and to write them in small capitals for emphasis. |

| 2 | PNs are generally catalogued in several subcategories (toponym, pseudonym, ethnonym, etc.); hence, instead of referring systematically to these subcategories, we will use generic terms highlighting their common properties regarding their lexical origin. With this in mind, onymisation, which is a type of lexical derivation, is defined as the process of the category change of an item into a PN. Therefore, an onymised item emanates from a process of onymisation. |

| 3 | Riffian is spoken in the Rif mountains and belongs to the Berber language family. This area is situated to the north of Morocco, and the speakers of this language are around 3/4 million. |

| 4 | According to Longobardi [11], this movement can also be covert and happen in the logical form on the basis of Germanic data by analysing the adjective–noun construction. |

| 5 | An expletive form must be also carefully distinguished from a null marker or zero morpheme that has no phonological form, but possesses meanings. Both can be symbolised by these notations, and , representing, respectively, an expletive form and a null marker. |

| 6 | These two models of grammatical description proposed by Hocket are presented as a general approach to model the whole linguistic system; they are not only restricted to morphology. In fact, the modern theoretical frameworks mentioned in this section are a mix of these two approaches. Depending on the cognitive component considered, the surfacing of a linguistic unit will be analysed as the result of an arrangement or/and process. Hence, we will only discuss their position with respect to morphology. Hocket, himself, proposes to see all combinations of immediate items as carried out by a process and defines, for that purpose, new processes. |

| 7 | The abbreviations used in this paper are as follows: SG = singular; PL = plural; F = feminine; M = masculine; V = verb; VP = verb phrase; N = noun; NP = noun phrase; P = pronoun; COL = collective; SING = singulative; DEF = definite; CONV = conversion, AUX = auxiliary, PAST = past, PRET = preterit. |

| 8 | Rules, like mathematical functions, can only establish a relation between an input or many and a single output. Non-deterministic morphological realisations imply that a single input is linked to several outputs. |

| 9 | Like with the Item and Process or Arrangement approach, templaticity is not a concept applied only in morphology. Different linguistic schools, such as Cognitive linguistics, abundantly use this notion for several aspects of language (phonology, syntax, semantics). For that reason, let us call this approach Item and Template to categorise the theoretical proposals assumed by all these scientific branches. As this cognitive construct is often under-emphasised in linguistics, we have chosen to highlight this feature and this is reflected in the title of this article and the name given to our model. |

| 10 | See also the conceptually related approach of Filter in Halle [23] dedicated to morphology and applying only in the lexicon. This approach was also adopted by Selkirk [48] by making manifest that morphology operates in the same way as syntax. Similarly, Anderson’s notion of Morphosyntactic Representation is better understood as an inflectional co-occurrence filter, since the inflectional morphemes are supposedly handled by syntax. |

| 11 | Stowell [52] proposes a comparable template called the theta-grid. Let us also mention Higginbotham’s approach [53] of the theta-grid. He proposes that underived nouns (e.g., dog) have a thematic grid as part of their lexical entry, while this template is generally only associated with deverbal nouns (e.g., destruction). As they usually do not take arguments, the definite article acts as a substitute to discharge this unfilled theta-role through the agency of theta-binding. This is not the approach underlined in this article. The fundamental similarity between our template and the theta-grid is founded only on the concept of templaticity, as a cognitive construct, reusable in different components of language. |

| 12 | This mentalistic algorithm mentions only the words formation processes. As to the meaning formation processes studied in this article, we will only consider the semantic shift and, more specifically, the semantic widening. Later, more will be disclosed about the formal mechanism of this process (see Section 3 and Section 4 and Figure 3 and Figure 4). |

| 13 | In Riffian, PN is the only category that can accept a lexicalised VP (e.g., tɾa ajθma-s ‘she has brothers’). Such a type of nouns are not found in CN, but that is not a universal observation. Some languages, like French or English (e.g., monsieur je-sais-tout ‘Mr Know-it-all’, les on-dit ‘hearsay’), can have CNs coming from VPs by conversion, but, in contrast, there are not established onymised VPs except for some names of artistic work. It is even possible to find typologically nouns derived from VPs with derivational affixes like in Tamil ([28], p. 17) or NPs derived from other NPs (see Section 3). |

| 14 | Over the course of this study, morphological derivation will designate any process changing the form of a base word during derivation. This may be any phonetic alteration affecting the root or/and any affix bound to the root, included the scheme (if different from the base word) and with the exception of the grammatical markers (i.e., feminine, plural, etc.). Instead, if the resultant word ignores any of these processes, then it is assumed that conversion is used. |

| 15 | Another case of morphological indeterminism is presented in Section 4.2. However, the elements involved differ from the overt anti-morphosyntactic shift, since the inputs under consideration are the cognitive sets and the outputs are the gender markers. |

| 16 | As the languages are constantly in gradual change over time, the mapping between these sets also mutates. To reflect this change in terms of notation, those functions can be written as follows: , with representing a new mapping correlated with temporal strata. |

| 17 | |

| 18 | When we will mention some Arabisms afterwards, this may refer to any of these Arabic varieties (Moroccan or Algerian Arabic varieties and Classical or Modern Standard Arabic). We will not distinguish them because the process of Riffanisation will be identical. |

| 19 | This restriction is exerted at the morphology level, not at the phonetic/phonology level. A loanword, a PN or CN, will comply with the Riffian phonetic/phonological system. Hereafter in this article, Riffanisation will refer only to this dimension. |

| 20 | In addition to the prefixation of the state, the feminine marker may also be affixed to derived countable nouns (for further details see Section 4.2). |

| 21 | We consider the demonyms a subpart of the ethnonyms. Under this umbrella is included any name designating a social community regardless of its size (family, clan, nation, etc.). In Riffian, a specific noun can be used as an ethnonym, i.e., a CN, or as a family name, i.e., a PN. For example, ajθ waɾjaʁeɾ ‘Ayt Waryaghel’ can be both. |

| 22 | It was decided to restrict this to demonyms and not to include all the CNs. The morphological phenomena that could be implicated with PNs and are not illustrated by these partial functions, such as the example (1(b)) given in the Introduction, will be dealt with in Figure 2; since, as claimed by our theoretical proposal, PNs and uncountable nouns in Riffian have similar templates and are affected by the same word-formation processes. |

| 23 | We assumed that the unmarked template of Ds includes the singular as the unmarked form, but this point is not totally solved. Regarding the process τ and some uncountable nouns (see Table 6, Type IIb), the unmarked template of some countable nouns, serving as a basis to construct PNs or uncountable nouns that bear the plural form, may contain the plural as an unmarked form instead of the singular. This is comparable to similar specificities found cross-linguistically (e.g., In English, the demonym French has only a plural meaning). |

| 24 | Some can have both types such as a-fɾˤansis (ω)/a-fɾˤansˤa-wi (ψ) ‘a French man’. Likewise, a toponym can come from a particular language (e.g., sːin ‘China’ from Arabic) and a demonym from another (e.g., a-ʃenw-i ‘Chinese person’ from French). |

| 25 | We consider that the borrowed PNs, except for hypocorisms, should be analysed as non-Riffanised and uncountable nouns in light of their morphology. They are certainly not Riffanised nouns, since they cannot affix any Berber morphemes, and they are not non-Riffanised countable nouns, since, from a PN, we can create a countable noun that bears the state (see Figure 1). |

| 26 | With this example, the V-state is absent, but not the C-state. This kind of noun with uncountable and countable meanings will be analysed in Section 3.3.2 and Section 3.3.3. |

| 27 | In Section 4.5, it will be demonstrated that this category of words encodes another grammatical feature, namely the collective meaning. Moreover, they have the same semiotic archetype as the words of Type I (see Figure 4 and Table 6). |

| 28 | This kind of discrepancies depending on languages can be seen between French and English when borrowing from Latin or Greek (non-anglicised: criteria, but Gallicised: critères (↰ in Greek: κρῐτήρῐᾰ) ‘criteria’). |

| 29 | Instances of Type I: fað ‘thirst”, ɾazˤ ‘hunger’, minta ‘mentha’, fɾijːu ‘pennyroyal’, zembu ‘sort of dish’, sajkuk ‘sort of dish’, beɾkukes ‘sort of dish’, seksu ‘couscous’, wuħβeɾ ‘soul’, χizːu ‘carrot’, dːedʒː ‘shame’, wetːˤu ‘separation’, qeɾnuʃ ‘arisarum’, mumːu ‘pupil’, ɾˤebːi ‘god’, midːen ‘people’, kisu ‘cheese’, faðˤis ‘lentisk’, βiβi ‘turkey’, tqaʃeɾ ‘sock’, dʒːwaɾu ‘ululation’, ɾiɾaɾt ‘play’, etc. |

| 30 | Instances of Type IIa: a-ʃefːaj ‘milk’, a-ʁɾum ‘bread’, a-ksum ‘meat’, a-zakuk ‘hair’, a-neβðu ‘summer’, ða-ʒɾist ‘winter’, etc. |

| 31 | Instances of Type IIb: ði-menːa ‘slander’, ði-meχsa ‘affection’, ði-mekɾaðˤ ‘scissors’, ði-melsa ‘clothing’, ði-nʕaʃin ‘money’, ði-megːa ‘witchcraft’, ði-ʁendin ‘pliers’, i-nʒan ‘dirt’, i-χʃiwen ‘dirt’, ði-nifin ‘peas’, ði-nzaɾ ‘nose’, ði-zˤewɾin ‘grape’, i-zˤettˤwen ‘pubic hair’, ði-mesna ‘knowledge’, ði-mezˤɾa ‘sight’, i-mezɾˤan ‘desire’, i-zɾan ‘poetry’, i-ɾðen ‘wheat’, i-kuffsan ‘spit’, i-wzan ‘sort of dish’, etc. |

| 32 | Instances of Type IIc: ða-ɾgazt ‘bravery’, ða-χsajθ ‘pumpkin’, a-ʁi ‘whey’, i-ʒði ‘sand’, a-ʃːiɾ ‘soured milk’, ði-msːi ‘fire’, a-nzˤaɾ ‘rain’, a-ðfel ‘snow’, a-ʒɾis ‘frost’, a-bedʒaʕ ‘mud’, a-dʒas ‘bran’, aðˤiɾ ‘grape’, a-ɾˤedːa ‘saliva’, ða-wengiθ ‘wisdom’, ða-hendiθ ‘prickly pear’, a-semːiðˤ ‘low temperature’, a-ʁimi ‘rest’, ða-feʤːaħθ ‘farming’, etc. |

| 33 | Instances of Type IIIa: ʃaɾ ‘soil’, juɾ ‘moon/month’, t-fawθ ‘light’, t-ʃamːa ‘football/ball’, ð-maziʁθ ‘Riffian language/woman’, ð-ʁufi ‘sorrow’, t-sːaʕeθ ‘hour/watch’, ð-ʁujːeθ ‘crying’, etc. |

| 34 | Instances of Type IIIb: ð-jawant ‘satiety’, t-fujθ ‘sun’, ɾum ‘straw’, miɾus ‘mud’, ð-ɾusi ‘butter’, t-nifest ‘ashes’, lːʁa ‘song’, dːaħiθ ‘pride’, ð-emzˤi ‘youth’, ð-ewseɾ ‘old age’, dːemːneθ ‘nature’, ð-emʁeɾ ‘adulthood’, dːemʕun ‘flu’, ð-eʁjeɾ ‘stupidity’, ð-esmedˤ ‘cold’, ð-esmem ‘acidity’, t-zadʒiθ ‘prayer’, t-zajaɾθ ‘vine’, t-zuɾa ‘moth’, t-muɾʁi ‘grasshopper’, dːist ‘pregnancy’, t-ɾaχt ‘clay’, ð-muʁɾi ‘sight’, t-ħimaɾθ ‘herd’, ð-mittˤ ‘navel’, zuj ‘thyme’, kufːu ‘froth’, t-namiθ ‘habit’, ð-ʁuɾi ‘study’, etc. |

| 35 | Instances of Type IV: t-sumːeθ ‘pillow’, jis ‘horse’, kuz ‘weevil’, fidʒːus ‘chick’, kuɾðu ‘flea’, fus ‘hand’, ðˤaɾ ‘foot’, fuð ‘knee’, t-siɾiθ ‘footwear’, ð-juga ‘harness’, ð-miʒːa ‘throat’, qabu ‘stick’, t-sudʒːeθ ‘basket’, zumbi ‘corn’, βaw ‘broad bean’, ʒiʒ ‘stake’, t-sa ‘liver’, ð-ʁattˤ ‘goat’, ð-ma ‘rim’, t-ʃamːeθ ‘dress’, qubiʕ ‘eurasian hoopoe’, ð-jazˤitt ‘chicken’, ð-baʁɾˤa ‘crow’, ð-ɾˤaʃːa ‘net’, ð-weɾʒuθ ‘window’, zagɾu ‘yoke’, qiʃː ‘horn’, t-χinʃiθ ‘sack’, ð-ʁeɾðˤent ‘scorpion’, t-kinda ‘mite’, fan ‘pan’, fiɾu ‘thread’, t-sːeɾseɾt ‘chain’, qaðus ‘pipe’, baðu ‘embankment’, etc. |

| 36 | A noun of address shares similar properties with PNs and, as seen previously (see also Section 4.4), PNs are also uncountable nouns from a morphological perspective. |

| 37 | Let us also cite this peculiar occurrence, when an ethnonym, which can be masculine and feminine, is transformed into a PN, notably a language name, the feminine marker will always be present. We suppose that the starting morphology was from the masculine form (e.g., Ethnomym: a-gɾinzi ‘Englishman’ → PN: ða-gɾinziθ ‘English’). Another irregular example, a kinship noun, which is morphosyntactically different from other nouns in Riffian, can be employed to form an uncountable noun (e.g., C: uma ‘brother (my)’ → U: ð-awmatt ‘brotherhood’). |

| 38 | However, a higher frequency of a certain morphology on countable nouns compared to uncountable nouns (a-semːiðˤ is the only example of its kind) can give a robust argument to postulate that these uncountable nouns were indeed countable). |

| 39 | Phonological phenomena can also be evidence of intermediary stages, especially when a resegmentation occurs (e.g., the form of a-mzˤiw ‘ogre/troll’ derives from a resegmentation of the plural form i-mzˤiwen ‘ogres/trolls’, its former form would be a-mzˤa, like its feminine counterpart ða-mzˤa/ði-mizˤiwin). |

| 40 | The composition function was ignored for simplification. Hence, the extended model is = and the homomorphic maps are ʊ=ʊ and ʊ=ʊ, such as and . |

| 41 | The examples (1(a)) in Section 1 and (2(a)) in Section 2.2.1 illustrate the initiation of the chain. |

| 42 | The examples (1(b)) in Section 1 and (2(b)) in Section 2.2.1 illustrate the termination of the chain. |

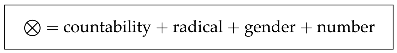

| 43 | Let us recall that, as seen in Section 5, this canonical form includes for other languages (e.g., English, French, Greek, etc.) the definiteness category: definiteness + countability + radical + gender + number. |

References

- Matthews, P. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Linguistics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystal, D. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadi, K. Système Verbal Rifain. Forme et Sens, Linguistique Tamazight (Nord Marocain); Number 6 in Études Ethno-linguistiques Maghreb-Sahara; Peeters Publishers: Leuven, Belgium, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lafkioui, M. Atlas Linguistique des variéTés Berbères du Rif; Berber Studies; Rüdiger Köppe Verlag: Cologne, Germany, 2007; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Brunschwig, J. Remarks on the Stoic theory of the proper noun. In Papers in Hellenistic Philosophy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994; pp. 39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Burge, T. Reference and Proper Names. J. Philos. 1973, 70, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.K.; Segal, G.M.A. Knowledge of Meaning: An Introduction to Semantic Theory; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allerton, D.J. The linguistic and sociolinguistic status of proper names What are they, and who do they belong to? J. Pragmat. 1987, 11, 61–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, R.A. Properhood. Language 2006, 82, 356–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Idrissi, M. Comment se dénomme-t-on en rifain/tmaziɣt? Etude onomastique: Essai théorique, approche psycholinguistique (partie I). Rev. Études Berbères 2015, 10, 309–339. [Google Scholar]

- Longobardi, G. Reference and Proper Names: A Theory of N-Movement in Syntax and Logical Form. Linguist. Inq. 1994, 25, 609–665. [Google Scholar]

- Abney, S.P. The English Noun Phrase in Its Sentential Aspect. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, E. A head-movement approach to construct-state noun phrases. Linguistics 1988, 26, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouhalla, J. Functional Categories and Parametric Variation; Theoretical linguistics; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, J.B. Demonstratives and reinforcers in Romance and Germanic languages. Lingua 1997, 102, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergnaud, J.R.; Zubizarreta, M.L. The Definite Determiner and the Inalienable Constructions in French and in English. Linguist. Inq. 1992, 23, 595–652. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. The Minimalist Program; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. Lectures on Government and Binding: The Pisa Lectures; Number 9 in Studies in Generative Grammar; Foris Publications; Foris: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, G.N. Reference to Kinds in English. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Massachusetts, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Chierchia, G. Reference to Kinds across Language. Nat. Lang. Semant. 1998, 6, 339–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moltmann, F. Names, Light Nouns, and Countability. Linguist. Inq. 2022, 54, 117–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partee, B.H. Montague Grammar and Transformational Grammar. Linguist. Inq. 1975, 6, 203–300. [Google Scholar]

- Halle, M. Prolegomena to a Theory of Word Formation. Linguist. Inq. 1973, 4, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jackendoff, R. Morphological and Semantic Regularities in the Lexicon. Language 1975, 51, 639–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronoff, M. Word Formation in Generative Grammar; Number 1 in Linguistic Inquiry Monographs; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Aronoff, M. Morphology by Itself: Stems and Inflectional Classes; Number 22 in Linguistic Inquiry Monographs; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, R. On the Organization of the Lexicon. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, R. Deconstructing Morphology: Word Formation in Syntactic Theory; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pustejovsky, J. The Generative Lexicon; Language, Speech, and Communication series; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.R. A-Morphous Morphology; Number 62 in Cambridge Studies in Linguistics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halle, M.; Marantz, A. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The View from Building 20; Hale, K., Keyser, S.J., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993; pp. 111–176. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, R. Lexeme-Morpheme Base Morphology: A General Theory of Inflection and Word Formation; SUNY series in Linguistics; Suny Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jackendoff, R.; Audring, J. The Texture of the Lexicon: Relational Morphology and the Parallel Architecture; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Robins, R.H. General Linguistics: An Introductory Survey; Number 2; Longman Linguistics Library: Longman, UK, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, P.H. Inflectional Morphology: A Theoretical Study Based on Aspects of Latin Verb Conjugation; Number I in Cambridge Text-books in Linguistics; University Press Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Zwicky, A.M. Some choices in the theory of morphology. In Formal Grammar: Theory and Implementation; Levine, R., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 327–371. [Google Scholar]

- Stump, G.T. Inflectional Morphology: A Theory of Paradigm Structure; Number 93 in Cambridge Studies in Linguistics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hockett, C.F. Two Models of Grammatical Description. Word 1954, 10, 210–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, L. Language; Holt, Rinehart & Winston: New York, NY, USA, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M. The Mirror Principle and Morphosyntactic Explanation. Linguist. Inq. 1985, 16, 373–415. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. Remarks on Nominalization. In Readings in English Transformational Grammar; Jacobs, R.A., Rosenbaum, P.S., Eds.; Ginn: Boston, MA, USA, 1970; pp. 184–221. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, J.T.; Stong-Jensen, M. Morphology Is in the Lexicon! Linguist. Inq. 1984, 15, 474–498. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.R. Where is Morphology? Linguist. Inq. 1982, 13, 571–612. [Google Scholar]

- Booij, G. Against split morphology. In Yearbook of Morphology 1993; Booij, G., Van Marle, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouhalla, J. Agreement Features, Agreement and Antiagreement. Nat. Lang. Linguist. Theory 2005, 23, 655–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, P.H. Some Concepts in Word-and-Paradigm Morphology. Found. Lang. 1965, 1, 268–289. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1965; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk, E.O. The Syntax of Words; Number 7 in Linguistic inquiry monographs; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Jackendoff, R. X Syntax: A Study of Phrase Structure; Number 2 in Linguistic inquiry monographs; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. Syntactic Structures; Number 4 in Janua linguarum; Mouton: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, P.H. Problems of selection in transformational grammar. J. Linguist. 1965, 1, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stowell, T.A. Origins of Phrase Structure. Ph.D. Thesis, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Higginbotham, J. On Semantics. Linguist. Inq. 1985, 16, 547–593. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, E. Argument Structure and Morphology. Linguist. Rev. 1981, 1, 81–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, J.P. Stems and Paradigms. Language 2003, 79, 737–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiparsky, P. Some Consequences of Lexical Phonology. Phonol. Yearb. 1985, 2, 85–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karttunen, L. Word Play. Comput. Linguist. 2007, 33, 443–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankamer, J.; Mikkelsen, L. When Movement Must Be Blocked: A Reply to Embick and Noyer. Linguist. Inq. 2005, 36, 85–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, W.R. Principles of the Self-Organizing System. In Systems Research for Behavioral Science: A Sourcebook; Buckley, W., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- El Hankari, A. The Construct State in Tarifit Berber. Lingua 2014, 148, 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouhalla, J. The Syntax of Head Movement: A Study of Berber. Ph.D. Thesis, University of London, London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Guerssel, M. A phonological analysis of the construct state in Berber. Linguist. Anal. 1983, 11, 309–329. [Google Scholar]

- Serhoual, M. Dictionnaire Tarifit-françAis. Ph.D. Thesis, Abdelmalek Essaâdi University, Tétouan, Morocco, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bendjaballah, S.; Haiden, M. A Typology of Emptiness in Templates. In Sounds of Silence: Empty Elements in Phonology and Syntax; Hartmann, J., Hegedűs, V., Riemsdijk, H.v., Eds.; North-Holland Linguistic Series: Linguistic Variations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; Volume 63, pp. 21–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shlonsky, U. A note on labeling, Berber states and VSO order. In The Form of Structure, the Structure of Form: Essays in honor of Jean Lowenstamm; Bendjaballah, S., Faust, N., Lahrouchi, M., Lampitelli, N., Eds.; Language Faculty and Beyond—Internal and External Variation in Linguistics; John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 12, pp. 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creissels, D. Construct forms of nouns in African languages. In Proceedings of the Conference on Language Documentation and Linguistic Theory 2, London, UK, 13–14 November 2009; Austin, P.K., Bond, O., Charette, M., Nathan, D., Sells, P., Eds.; SOAS: London, UK, 2009; pp. 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols, J. Head-marking and dependent-marking grammar. Language 1986, 62, 56–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vycichl, W. L’article défini du berbére. In Mémorial André Basset (1895–1956); Adrien-Maisonneuve: Paris, France, 1957; pp. 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Longobardi, G. Formal Syntax, Diachronic Minimalism, and Etymology: The History of French, Chez. Linguist. Inq. 2001, 32, 275–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penchoen, T.G. Tamazight of the Ayt Ndhir; Afroasiatic dialects, Undena Publications; Undena: Malibu, CA, USA, 1973; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Basset, A. Articles de Dialectologie Berbère; Collection linguistique/Société de linguistique de Paris; Klincksieck: Paris, France, 1959; Volume 58. [Google Scholar]

- Naït-Zerrad, K. Dictionnaire des Racines Berbères (Formes Attestées), I; Number 371 in SELAF; Peeters: Paris, France; Louvain, Belgium, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Masqueray, É. Dictionnaire Français-Touareg: Dialecte des Taitoq; Number XI in Bulletin de correspondance africaine; Ernest Leroux éditeur: Paris, France, 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Motylinski, G.A.d.C. Le Dialecte Berbère de R’edamès; Number XXVIII in Bulletin de correspondance africaine; Ernest Leroux éditeur: Paris, France, 1904. [Google Scholar]

- Basset, R. Étude sur la Zenatia de l’Ouarsenis et du Maghreb Central; Number XV in Bulletin de correspondance africaine; Ernest Leroux éditeur: Paris, France, 1895. [Google Scholar]

- Booij, G.; Audring, J. Construction Morphology and the Parallel Architecture of Grammar. Cogn. Sci. 2017, 41, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fassi Fehri, A. Constructing Feminine to Mean: Gender, Number, Numeral, and Quantifier Extensions in Arabic; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Taïfi, M. Dictionnaire Tamazight-Français: (Parlers du Maroc Central); L’Harmattan-Awal: Paris, France, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Boumalk, A.; Bounfour, A. Vocabulaire Usuel du Tachelhit: Tachelhit-Français; Centre Tarik ibn Zyad: Les Mureaux, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, S. Grammatical number and the scale of individuation. Language 2018, 94, 527–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrissi, A.; Prunet, J.F.; Béland, R. On the Mental Representation of Arabic Roots. Linguist. Inq. 2008, 39, 221–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuraw, K.; Hayes, B. Intersecting constraint families: An argument for harmonic grammar. Language 2017, 93, 497–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Riffian | English | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Radical | Article | Radical | ||

| CN | a | ɾgaz | man | the | man |

| N/A | seksu | couscous | N/A | life | |

| PN | N/A | muħend | Muhend | N/A | John |

| a | ʒðiɾ | Ajdir | the | Arctic | |

| aqzin | dog.SG.M |

| ð-aqzin-t | dog.SG.F |

| iqzin-en | dog.PL.M |

| ð-iqzin-in | dog.PL.F |

| Free State | Annexation State |

|---|---|

| a-qzin | u-qzin ⇐ /we-qzin/ |

| ða-qzint | ðe-qzint |

| i-qzinen | je-qzinen ⇐ /we-qzinen/ |

| ði-qzinin | ðe-qzinin |

| Uncountable Nouns | Countable Nouns | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabic | ↱ | tːefːaħ ‘apples’ | → | ða-tːefːaħθ ‘an apple’ |

| ɾeʃːin ‘oranges’ | ða-ɾeʃːint ‘an orange’ | |||

| sːˤaħafa ‘journalism’ | ↱ | a-sˤaħafi ‘a journalist’ | ||

| French | ↱ | ɾpuɾis ‘police’ | a-puɾisi ‘a policeman’ | |

| Riffian | seksu ‘couscous’ | → | ða-seksuθ ‘a couscoussier’ |

| Semiotic Archetypes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | → | B | → | C | |

| PN | Bougie | The-Pentagon | |||

| CN | la-bougie the-pentagon | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El Idrissi, M. Semantic and Morphosyntactic Differences among Nouns: A Template-Based and Modular Cognitive Model. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12121777

El Idrissi M. Semantic and Morphosyntactic Differences among Nouns: A Template-Based and Modular Cognitive Model. Mathematics. 2024; 12(12):1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12121777

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl Idrissi, Mohamed. 2024. "Semantic and Morphosyntactic Differences among Nouns: A Template-Based and Modular Cognitive Model" Mathematics 12, no. 12: 1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12121777

APA StyleEl Idrissi, M. (2024). Semantic and Morphosyntactic Differences among Nouns: A Template-Based and Modular Cognitive Model. Mathematics, 12(12), 1777. https://doi.org/10.3390/math12121777