Semi-Supervised Multi-Label Dimensionality Reduction Learning by Instance and Label Correlations

Abstract

1. Introduction

- •

- The Hilbert–Schmidt Independence Criterion (HSIC) [14] has been mathematically shown to maximize the dependence between the original feature description and the associated class label. Motivated by this, we use the matrix factorization technique to reconstruct the HSIC empirical estimator in MDDM [4] into a least squares problem, enabling the label propagation mechanism to be seamlessly incorporated into the dimensionality reduction learning model.

- •

- Consideration is given to the instance correlations. In order to use instance correlations in dimensionality reduction, we introduce a new assumption, which states that if two instances have a high degree of correlation in the original feature space, they should also have a high degree of correlation in the low-dimensional feature space. The instance correlations are assessed using the k-nearest neighbor approach.

- •

- Through the use of the -norm and -norm regularization terms to select the appropriate features, the specific features and the common features of the feature space are simultaneously investigated in our method, which helps to enhance the performance of dimensionality reduction.

2. Related Work

2.1. Dimensionality Reduction

2.2. The Brief Review of HSIC and MDDM

3. Materials and Methods

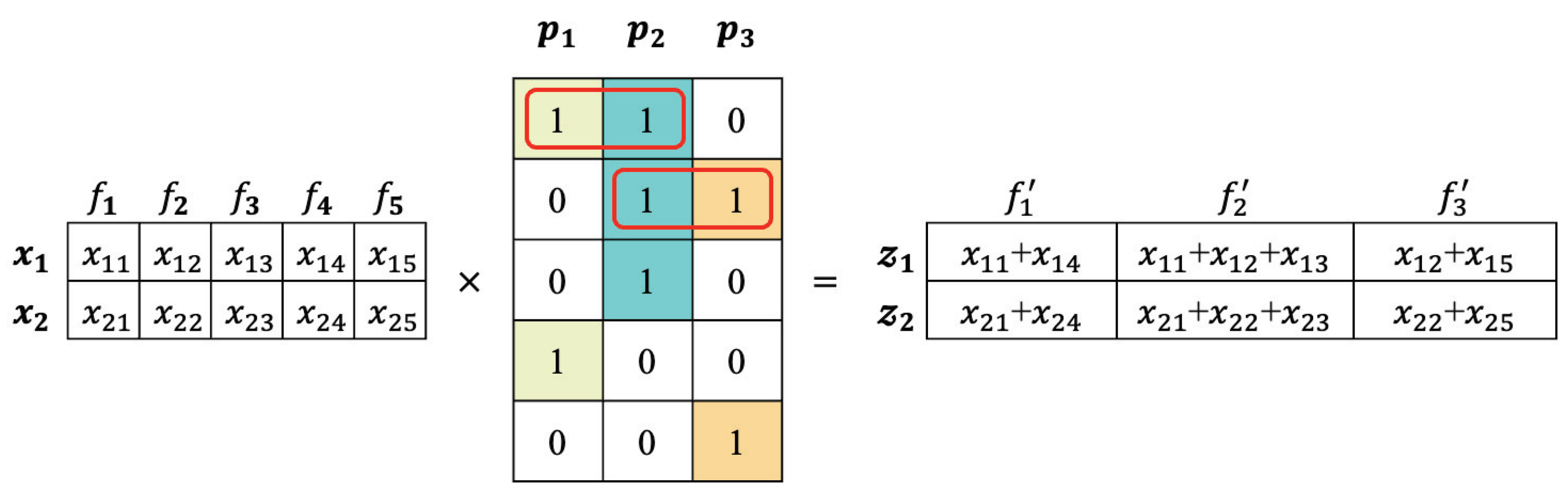

3.1. Preliminaries

3.2. Obtaining Soft Label by Label Propagation

3.2.1. Neighborhood Graph Construction

3.2.2. Label Propagation

3.3. Dimensionality Reduction

3.3.1. Design of the Semi-Supervised Mode

3.3.2. Reformulate MDDM to Least Square

3.3.3. Incorporating Instance Correlations

3.3.4. Incorporating Specific and Common Features

3.3.5. Optimization

| Algorithm 1 SMDR-IC: Semi-supervised Multi-label Dimensionality Reduction Learning by Instance and Label Correlations |

|

4. Results

4.1. Benchmark Data Sets

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.3. Comparison Methods and Parameters Settings

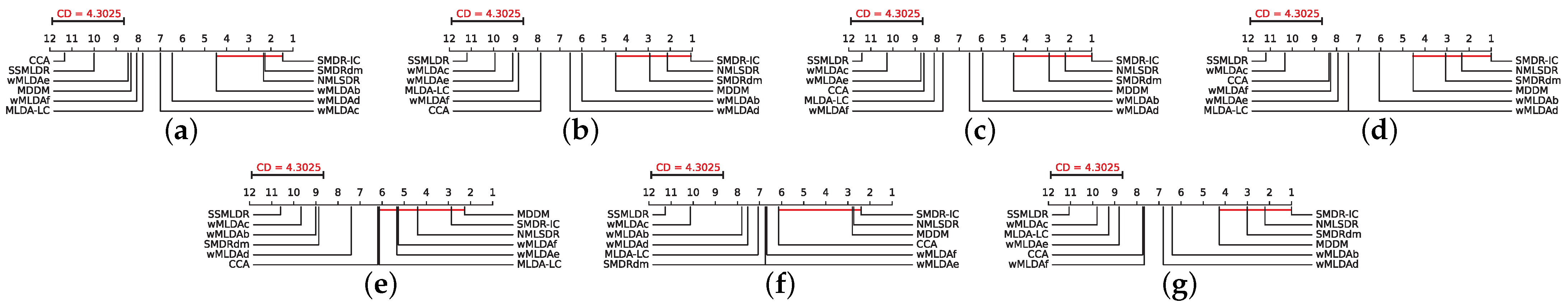

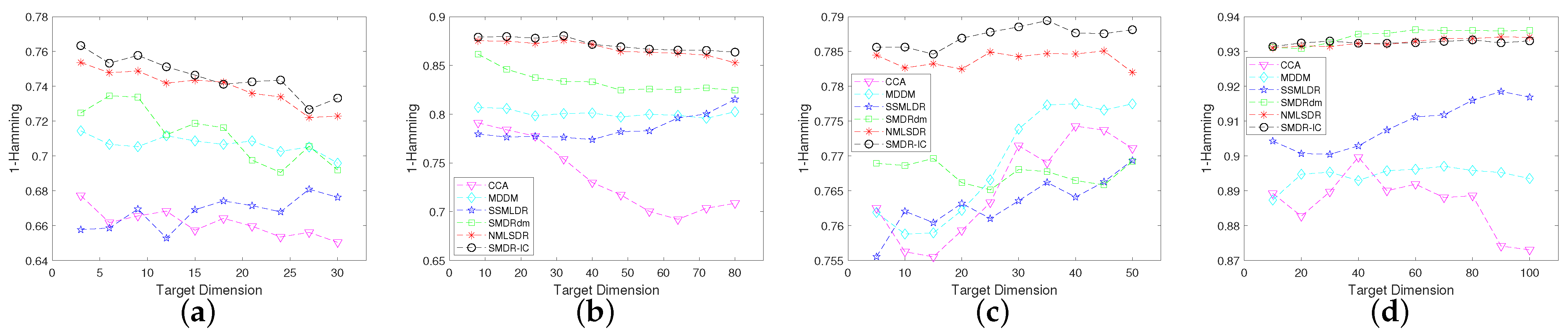

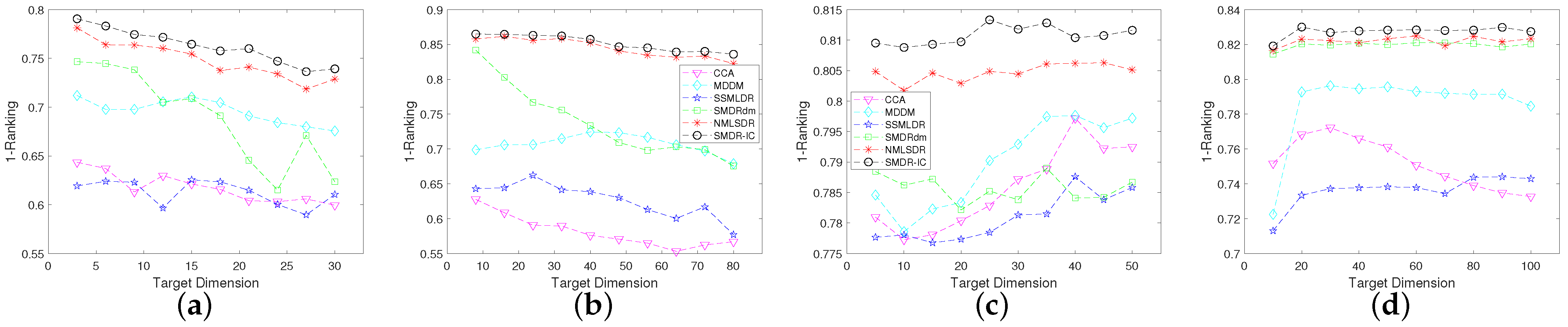

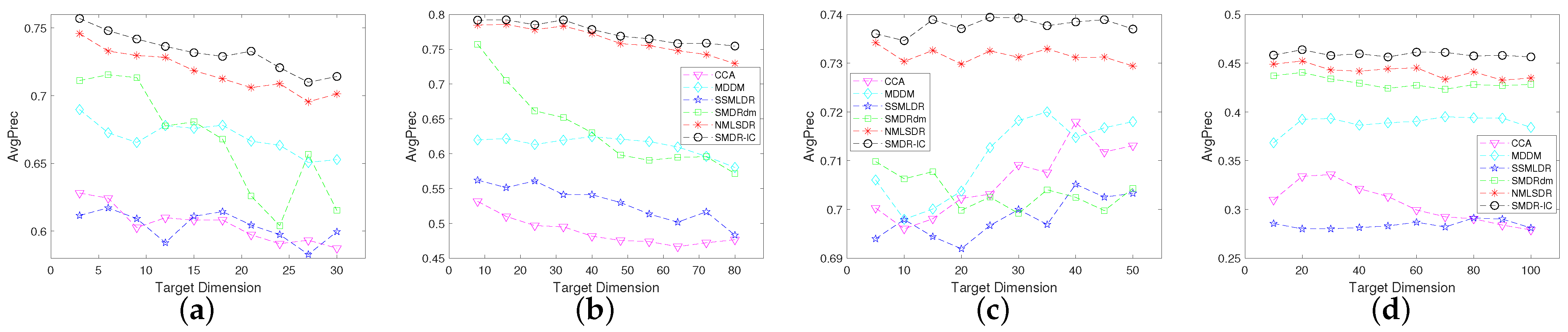

4.4. Experimental Results

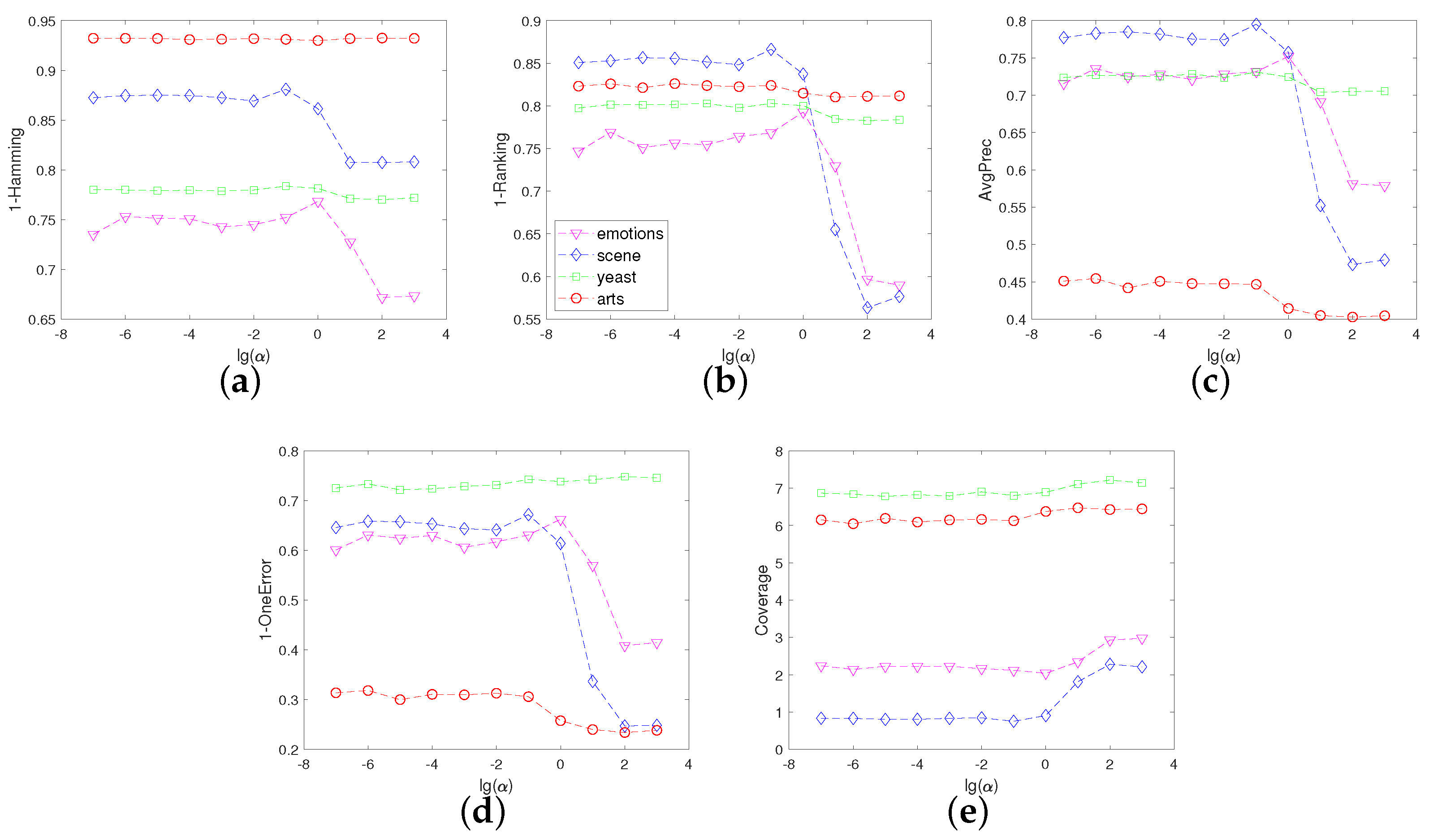

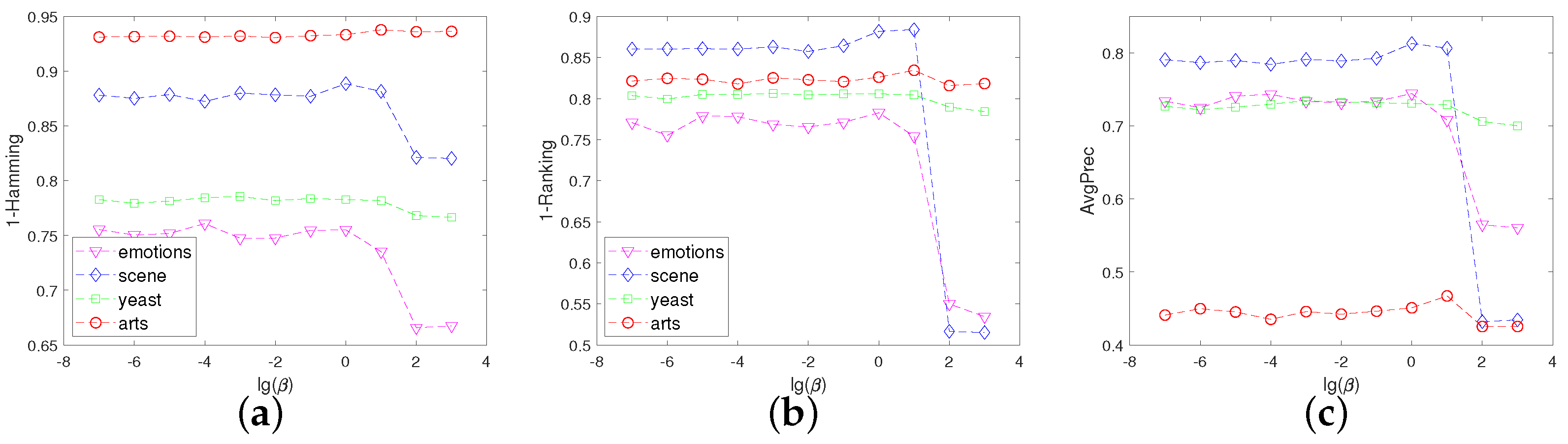

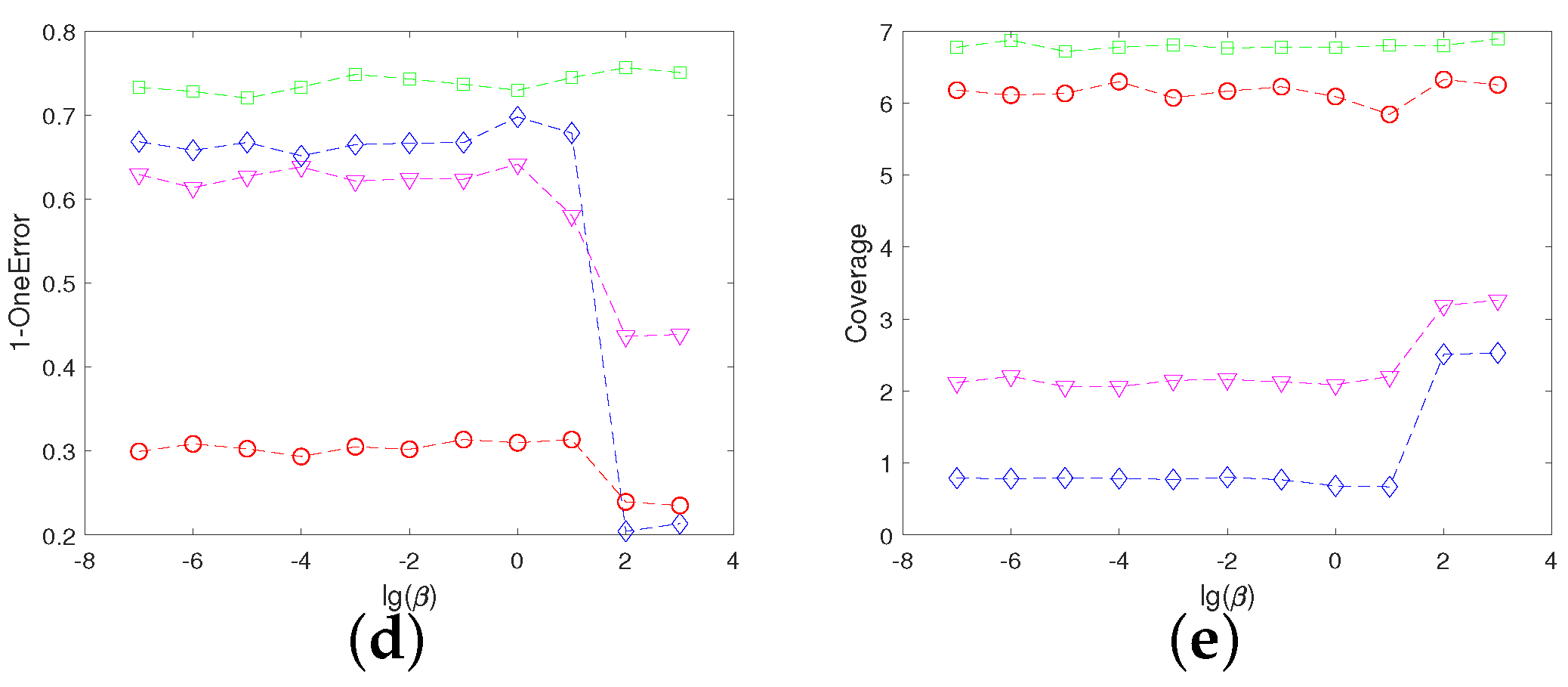

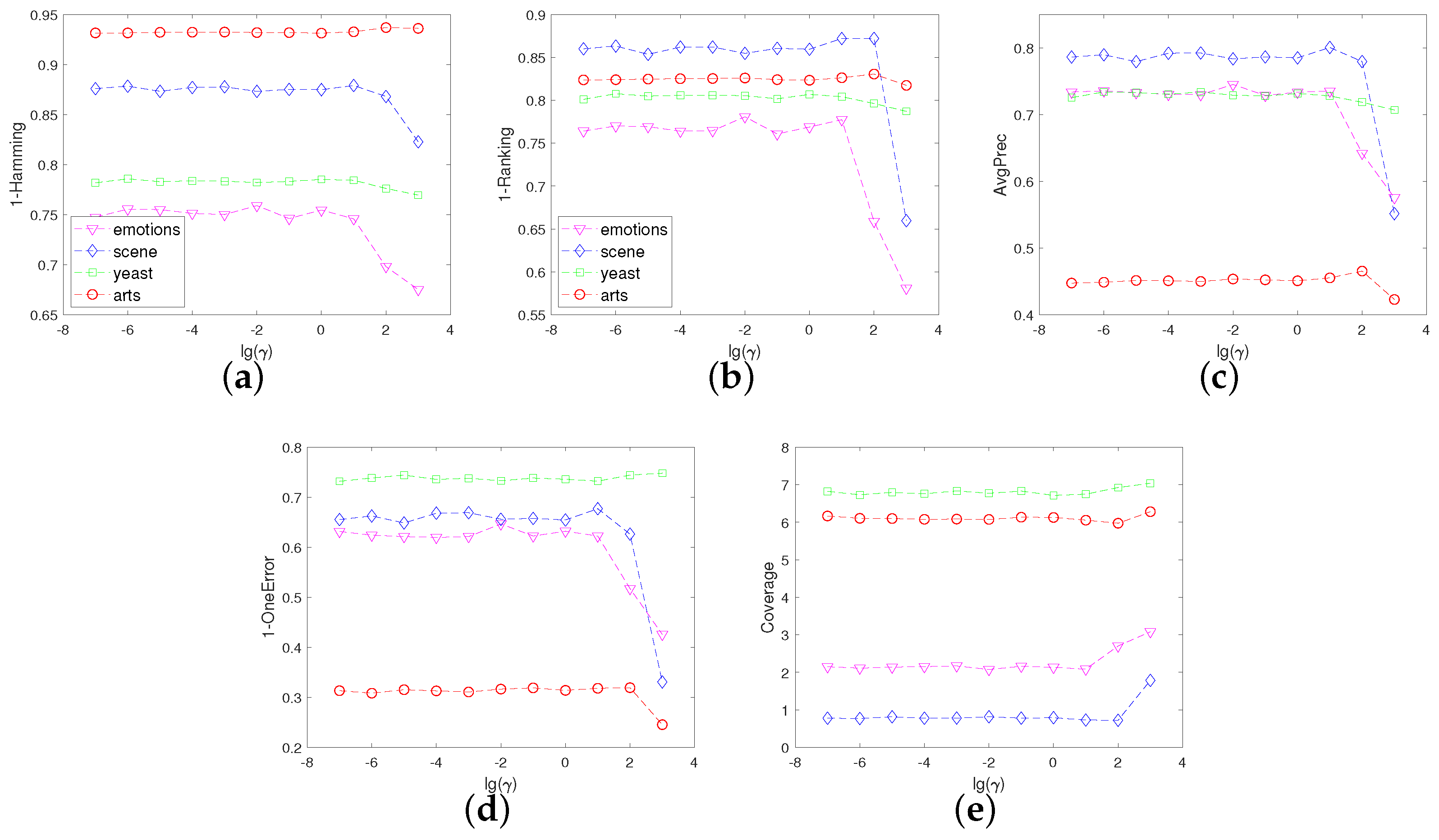

4.5. Sensitivity Analysis of Parameters

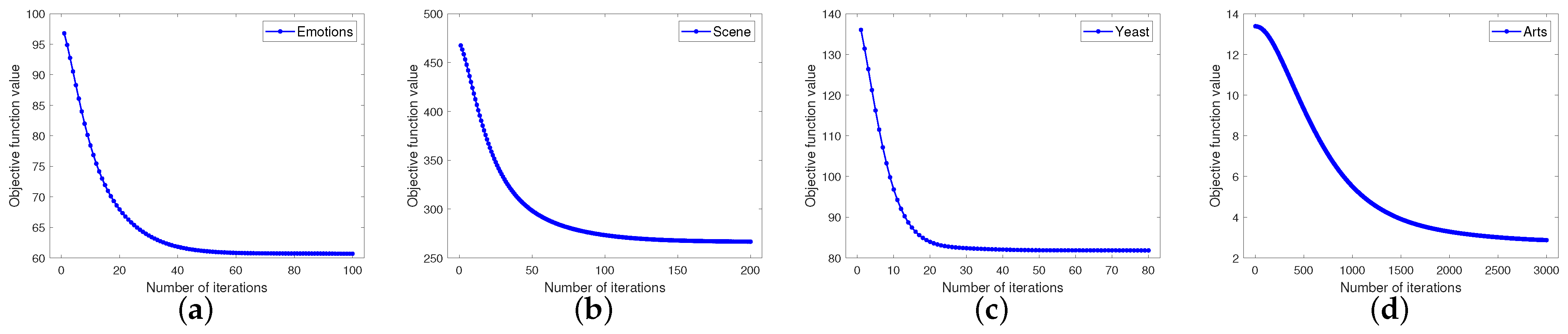

4.6. Convergence and Time Complexity Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, L.; Ji, S.; Ye, J. Multi-Label Dimensionality Reduction; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bellman, R. Dynamic programming and Lagrange multipliers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1956, 42, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siblini, W.; Kuntz, P.; Meyer, F. A review on dimensionality reduction for multi-label classification. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2021, 33, 839–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.H. Multilabel dimensionality reduction via dependence maximization. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data (TKDD) 2010, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardoon, D.R.; Szedmak, S.; Shawe-Taylor, J. Canonical correlation analysis: An overview with application to learning methods. Neural Comput. 2004, 16, 2639–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Ding, C.; Huang, H. Multi-label linear discriminant analysis. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV, Heraklion, Greece, 5–11 September 2010; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, X.; Ng, M.K.; Zhou, Z.H. Transductive multilabel learning via label set propagation. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2011, 25, 704–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B.; Davidson, I. Semi-supervised dimension reduction for multi-label classification. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Atlanta, GA, USA, 11–15 July 2010; pp. 569–574. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, B.; Hou, C.; Nie, F.; Yi, D. Semi-supervised multi-label dimensionality reduction. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 16th International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), Barcelona, Spain, 12–15 December 2016; pp. 919–924. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Tan, Q.; Jia, L.; Yu, G. Semi-supervised multi-label dimensionality reduction based on dependence maximization. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 21927–21940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, F.; Huang, H.; Cai, X.; Ding, C. Efficient and robust feature selection via joint l2,1-norms minimization. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–9 December 2010; Volume 23, pp. 1813–1821. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Li, Y.; Gao, W.; Zhang, P.; Hu, J. Multi-label feature selection with shared common mode. Pattern Recognit. 2020, 104, 107344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, P.; Hu, X.; Yu, K. Learning common and label-specific features for multi-Label classification with correlation information. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 121, 108259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretton, A.; Bousquet, O.; Smola, A.; Schölkopf, B. Measuring statistical dependence with Hilbert-Schmidt norms. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Algorithmic Learning Theory, Singapore, 8–11 October 2005; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe, I.T.; Cadima, J. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roweis, S.T.; Saul, L.K. Nonlinear dimensionality reduction by locally linear embedding. Science 2000, 290, 2323–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkin, M.; Niyogi, P. Laplacian eigenmaps and spectral techniques for embedding and clustering. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2001, 14, 585–591. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, F.; Xu, D.; Tsang, I.W.H.; Zhang, C. Flexible manifold embedding: A framework for semi-supervised and unsupervised dimension reduction. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2010, 19, 1921–1932. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deerwester, S.; Dumais, S.T.; Furnas, G.W.; Landauer, T.K.; Harshman, R. Indexing by latent semantic analysis. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1990, 41, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Yu, S.; Tresp, V. Multi-label informed latent semantic indexing. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Salvador, Brazil, 15–19 August 2005; pp. 258–265. [Google Scholar]

- Hotelling, H. Relations between two sets of variates. Biometrika 1936, 28, 321–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ji, S.; Ye, J. Canonical correlation analysis for multilabel classification: A least-squares formulation, extensions, and analysis. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2010, 33, 194–200. [Google Scholar]

- Pacharawongsakda, E.; Theeramunkong, T. A two-stage dual space reduction framework for multi-labe classification. In Proceedings of the Trends and Applications in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Delhi, India, 11 May 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 330–341. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.A. The use of multiple measurements in taxonomic problems. Ann. Eugen. 1936, 7, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Lee, M. On applying linear discriminant analysis for multi-labeled problems. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2008, 29, 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yan, J.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Q. Document transformation for multi-label feature selection in text categorization. In Proceedings of the Seventh IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM 2007), Omaha, NE, USA, 28–31 October 2007; pp. 451–456. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Chen, X.W. KNN: Soft relevance for multi-label classification. In Proceedings of the 19th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26–30 October 2010; pp. 349–358. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. A weighted linear discriminant analysis framework for multi-label feature extraction. Neurocomputing 2018, 275, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Zhao, K.; Lu, H. Multi-label linear Ddiscriminant analysis with locality consistency. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8–13 December 2014; Loo, C.K., Yap, K.S., Wong, K.W., Teoh, A., Huang, K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 386–394. [Google Scholar]

- Shu, X.; Lai, D.; Xu, H.; Tao, L. Learning shared subspace for multi-label dimensionality reduction via dependence maximization. Neurocomputing 2015, 168, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gönen, M. Coupled dimensionality reduction and classification for supervised and semi-supervised multilabel learning. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2014, 38, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Zhang, W. Semisupervised multilabel learning with joint dimensionality reduction. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2016, 23, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaschko, M.B.; Shelton, J.A.; Bartels, A.; Lampert, C.H.; Gretton, A. Semi-supervised kernel canonical correlation analysis with application to human fMRI. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2011, 32, 1572–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, P.; Guo, Y.J.; Wu, M. Multi-label dimensionality reduction based on semi-supervised discriminant analysis. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. 2010, 17, 1310–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, M.; Van Driessen, K. Fast and robust discriminant analysis. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2004, 45, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croux, C.; Dehon, C. Robust linear discriminant analysis using S-estimators. Can. J. Stat. 2001, 29, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, M.; Rousseeuw, P.J.; Van Aelst, S. High-breakdown robust multivariate methods. Stat. Sci. 2008, 23, 92–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalsen, K.Ø.; Soguero-Ruiz, C.; Bianchi, F.M.; Jenssen, R. Noisy multi-label semi-supervised dimensionality reduction. Pattern Recognit. 2019, 90, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golub, G.H.; Van Loan, C.F. Matrix Computations; JHU Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Huang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Feng, W. Multi-label learning with label specific features using correlation information. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 11474–11484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.J.; Zhou, Z.H. Multi-Label Learning by Exploiting Label Correlations Locally; AAAI Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Ganesh, A.; Wright, J.; Wu, L.; Chen, M.; Ma, Y. Fast Convex Optimization Algorithms for Exact Recovery of a Corrupted Low-Rank Matrix; Report no. UILU-ENG-09-2214, DC-246; Coordinated Science Laboratory: Urbana, IL, USA, 2009; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2142/74352 (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Zhang, M.L.; Zhou, Z.H. ML-KNN: A lazy learning approach to multi-label learning. Pattern Recognit. 2007, 40, 2038–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demšar, J. Statistical comparisons of classifiers over multiple data sets. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2006, 7, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Domin | #Instances | #Attributes | #Labels | Cardinality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotions | music | 593 | 72 | 6 | 1.87 |

| Scene | image | 2407 | 294 | 6 | 1.07 |

| Corel5k | images | 5000 | 499 | 374 | 3.52 |

| Yeast | biology | 2417 | 103 | 14 | 4.23 |

| Arts | text | 5000 | 695 | 26 | 1.65 |

| Business | text | 5000 | 658 | 30 | 1.60 |

| Computers | text | 5000 | 1023 | 33 | 1.51 |

| Education | text | 5000 | 827 | 33 | 1.46 |

| Entertainment | text | 5000 | 961 | 21 | 1.41 |

| Health | text | 5000 | 919 | 32 | 1.64 |

| Recreation | text | 5000 | 910 | 22 | 1.43 |

| Reference | text | 5000 | 1191 | 33 | 1.17 |

| Science | text | 5000 | 1116 | 40 | 1.45 |

| Social | text | 5000 | 1571 | 39 | 1.28 |

| Society | text | 5000 | 955 | 27 | 1.67 |

| Dataset | Metrics | CCA | wMLDAb | wMLDAe | wMLDAc | wMLDAf | wMLDAd | MLDA-LC | MDDM | SSMLDR | SMDRdm | NMLSDR | SMDR-IC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotions | 1-Hamming | 0.6624 | 0.6865 | 0.6786 | 0.6766 | 0.6768 | 0.6837 | 0.6823 | 0.6991 | 0.6657 | 0.7317 | 0.7507 | 0.7602 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.6195 | 0.6532 | 0.6533 | 0.6397 | 0.6505 | 0.6507 | 0.6427 | 0.7010 | 0.6223 | 0.7432 | 0.7741 | 0.7872 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.6105 | 0.6397 | 0.6410 | 0.6247 | 0.6242 | 0.6343 | 0.6370 | 0.6738 | 0.6117 | 0.7106 | 0.7425 | 0.7507 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.4607 | 0.4972 | 0.4792 | 0.4685 | 0.4534 | 0.4843 | 0.4949 | 0.5382 | 0.4579 | 0.5916 | 0.6404 | 0.6466 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.3703 | 0.3614 | 0.3923 | 0.3688 | 0.3730 | 0.3779 | 0.3895 | 0.4699 | 0.3393 | 0.4930 | 0.5329 | 0.5373 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.3902 | 0.3873 | 0.4047 | 0.3896 | 0.3888 | 0.3985 | 0.4072 | 0.4837 | 0.3522 | 0.5151 | 0.5541 | 0.5643 | |

| Coverage | 2.8579 | 2.6208 | 2.6421 | 2.7062 | 2.6174 | 2.6848 | 2.7096 | 2.4506 | 2.8152 | 2.2624 | 2.1118 | 2.0287 | |

| Scene | 1-Hamming | 0.7762 | 0.8040 | 0.7849 | 0.7772 | 0.7862 | 0.7850 | 0.7779 | 0.8056 | 0.7806 | 0.8649 | 0.8759 | 0.8780 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.6487 | 0.6686 | 0.6564 | 0.6468 | 0.6639 | 0.6532 | 0.6327 | 0.7142 | 0.6503 | 0.8487 | 0.8621 | 0.8660 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.5609 | 0.5845 | 0.5790 | 0.5656 | 0.5823 | 0.5745 | 0.5470 | 0.6328 | 0.5654 | 0.7688 | 0.7881 | 0.7949 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.3573 | 0.3956 | 0.3888 | 0.3647 | 0.3877 | 0.3816 | 0.3409 | 0.4548 | 0.3663 | 0.6296 | 0.6584 | 0.6710 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.3354 | 0.3436 | 0.3760 | 0.3450 | 0.3731 | 0.3714 | 0.3164 | 0.4442 | 0.3432 | 0.6012 | 0.6275 | 0.6365 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.3378 | 0.3440 | 0.3760 | 0.3479 | 0.3713 | 0.3693 | 0.3175 | 0.4413 | 0.3476 | 0.5954 | 0.6221 | 0.6311 | |

| Coverage | 1.8306 | 1.7408 | 1.7864 | 1.8393 | 1.7665 | 1.8183 | 1.9176 | 1.5124 | 1.8371 | 0.8465 | 0.7744 | 0.7592 | |

| Corel5k | 1-Hamming | 0.9872 | 0.9898 | 0.9873 | 0.9889 | 0.9876 | 0.9881 | 0.9891 | 0.9890 | 0.9898 | 0.9905 | 0.9905 | 0.9905 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8329 | 0.8395 | 0.8313 | 0.8346 | 0.8317 | 0.8321 | 0.8325 | 0.8356 | 0.8373 | 0.8422 | 0.8416 | 0.8465 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.1491 | 0.2027 | 0.1643 | 0.1517 | 0.1635 | 0.1673 | 0.1626 | 0.1670 | 0.1646 | 0.2162 | 0.2102 | 0.2235 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.1124 | 0.2076 | 0.1373 | 0.1034 | 0.1324 | 0.1365 | 0.1199 | 0.1373 | 0.1223 | 0.2271 | 0.2148 | 0.2382 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0077 | 0.0082 | 0.0158 | 0.0058 | 0.0159 | 0.0158 | 0.0118 | 0.0099 | 0.0029 | 0.0013 | 0.0010 | 0.0024 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.0431 | 0.0689 | 0.0814 | 0.0317 | 0.0743 | 0.0730 | 0.0450 | 0.0538 | 0.0165 | 0.0053 | 0.0053 | 0.0118 | |

| Coverage | 131.5283 | 130.7983 | 133.2597 | 130.2415 | 133.1978 | 135.4703 | 133.7845 | 129.6946 | 128.3927 | 129.4937 | 129.6759 | 127.7015 | |

| Yeast | 1-Hamming | 0.7555 | 0.7721 | 0.7588 | 0.7596 | 0.7639 | 0.7574 | 0.7616 | 0.7602 | 0.7574 | 0.7699 | 0.7819 | 0.7839 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.7822 | 0.7923 | 0.7813 | 0.7788 | 0.7835 | 0.7826 | 0.7790 | 0.7795 | 0.7757 | 0.7905 | 0.8021 | 0.8065 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.7015 | 0.7183 | 0.6981 | 0.6962 | 0.7025 | 0.6999 | 0.7001 | 0.6971 | 0.6927 | 0.7098 | 0.7274 | 0.7331 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.6803 | 0.7244 | 0.6769 | 0.6722 | 0.6755 | 0.6719 | 0.6862 | 0.6663 | 0.6756 | 0.7140 | 0.7240 | 0.7348 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.3651 | 0.2814 | 0.3498 | 0.3278 | 0.3448 | 0.3518 | 0.3252 | 0.3569 | 0.3012 | 0.2914 | 0.3342 | 0.3367 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.5757 | 0.5638 | 0.5707 | 0.5591 | 0.5746 | 0.5697 | 0.5707 | 0.5743 | 0.5503 | 0.5718 | 0.6011 | 0.6041 | |

| Coverage | 7.0382 | 7.0471 | 7.0299 | 7.0948 | 7.0459 | 6.9999 | 7.1927 | 7.0360 | 7.2023 | 6.9979 | 6.7978 | 6.7818 | |

| Arts | 1-Hamming | 0.8834 | 0.9210 | 0.9046 | 0.9059 | 0.9035 | 0.9054 | 0.9020 | 0.8916 | 0.8993 | 0.9315 | 0.9321 | 0.9320 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.7734 | 0.7774 | 0.7557 | 0.7479 | 0.7696 | 0.7797 | 0.7257 | 0.7924 | 0.7426 | 0.8208 | 0.8234 | 0.8250 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.3355 | 0.3428 | 0.3324 | 0.2997 | 0.3439 | 0.3481 | 0.2605 | 0.3886 | 0.2852 | 0.4402 | 0.4479 | 0.4573 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.1883 | 0.1919 | 0.1903 | 0.1454 | 0.1940 | 0.1923 | 0.1062 | 0.2513 | 0.1426 | 0.2969 | 0.3138 | 0.3203 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0962 | 0.0619 | 0.0863 | 0.0677 | 0.0864 | 0.0828 | 0.0466 | 0.1222 | 0.0658 | 0.0880 | 0.1010 | 0.1009 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.1738 | 0.1154 | 0.1542 | 0.1070 | 0.1539 | 0.1496 | 0.0860 | 0.2225 | 0.1118 | 0.1625 | 0.1861 | 0.1896 | |

| Coverage | 7.3719 | 7.3199 | 7.9105 | 8.0955 | 7.5208 | 7.2357 | 8.6059 | 6.9166 | 8.2504 | 6.2077 | 6.1451 | 6.0962 | |

| Business | 1-Hamming | 0.9487 | 0.9581 | 0.9482 | 0.9482 | 0.9497 | 0.9580 | 0.9374 | 0.9500 | 0.9358 | 0.9692 | 0.9683 | 0.9698 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.9215 | 0.9315 | 0.9205 | 0.9219 | 0.9238 | 0.9294 | 0.9066 | 0.9322 | 0.9013 | 0.9495 | 0.9517 | 0.9550 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.7080 | 0.7315 | 0.6791 | 0.6820 | 0.6981 | 0.7413 | 0.6092 | 0.7354 | 0.5925 | 0.8544 | 0.8540 | 0.8618 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.6527 | 0.6611 | 0.5983 | 0.6065 | 0.6267 | 0.7100 | 0.5039 | 0.6748 | 0.4885 | 0.8625 | 0.8569 | 0.8667 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0640 | 0.0554 | 0.0639 | 0.0561 | 0.0691 | 0.0536 | 0.0634 | 0.0903 | 0.0650 | 0.0551 | 0.0902 | 0.0950 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.5008 | 0.5238 | 0.4651 | 0.4693 | 0.4871 | 0.5231 | 0.4103 | 0.5405 | 0.3874 | 0.6584 | 0.6636 | 0.6747 | |

| Coverage | 3.6281 | 3.2017 | 3.5773 | 3.6948 | 3.5538 | 3.4365 | 4.1116 | 3.2611 | 4.2259 | 2.7615 | 2.6629 | 2.5270 | |

| Computers | 1-Hamming | 0.9306 | 0.9452 | 0.9396 | 0.9431 | 0.9384 | 0.9439 | 0.9359 | 0.9368 | 0.9316 | 0.9553 | 0.9543 | 0.9560 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8601 | 0.8540 | 0.8494 | 0.8512 | 0.8536 | 0.8614 | 0.8481 | 0.8733 | 0.8154 | 0.8915 | 0.8968 | 0.9013 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.4433 | 0.4342 | 0.4120 | 0.4127 | 0.4244 | 0.4406 | 0.4072 | 0.4969 | 0.3301 | 0.5899 | 0.5929 | 0.6127 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.2911 | 0.2746 | 0.2557 | 0.2404 | 0.2559 | 0.2750 | 0.2543 | 0.3566 | 0.1823 | 0.5125 | 0.5007 | 0.5273 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0564 | 0.0495 | 0.0562 | 0.0328 | 0.0547 | 0.0452 | 0.0606 | 0.0794 | 0.0360 | 0.0512 | 0.0874 | 0.0974 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.2341 | 0.2212 | 0.2113 | 0.1688 | 0.2123 | 0.2098 | 0.2114 | 0.2951 | 0.1520 | 0.3622 | 0.3883 | 0.3871 | |

| Coverage | 5.8950 | 6.0295 | 6.2671 | 6.2404 | 6.1239 | 5.9851 | 6.2941 | 5.4448 | 7.4203 | 4.9139 | 4.7315 | 4.5519 | |

| Education | 1-Hamming | 0.9229 | 0.9417 | 0.9344 | 0.9436 | 0.9351 | 0.9418 | 0.9334 | 0.9267 | 0.9359 | 0.9518 | 0.9507 | 0.9528 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8549 | 0.8626 | 0.8375 | 0.8386 | 0.8474 | 0.8549 | 0.8533 | 0.8640 | 0.8030 | 0.8826 | 0.8830 | 0.8869 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.3721 | 0.3762 | 0.3378 | 0.3237 | 0.3502 | 0.3618 | 0.3634 | 0.4111 | 0.2545 | 0.4567 | 0.4628 | 0.4791 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.1997 | 0.1838 | 0.1708 | 0.1389 | 0.1787 | 0.1767 | 0.1930 | 0.2481 | 0.0915 | 0.2906 | 0.3024 | 0.3207 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0640 | 0.0480 | 0.0531 | 0.0295 | 0.0560 | 0.0453 | 0.0587 | 0.0794 | 0.0324 | 0.0460 | 0.0655 | 0.0605 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.2022 | 0.1470 | 0.1533 | 0.0795 | 0.1554 | 0.1324 | 0.1732 | 0.2432 | 0.0825 | 0.1524 | 0.1971 | 0.1870 | |

| Coverage | 5.6981 | 5.4315 | 6.3093 | 6.2081 | 5.9069 | 5.6680 | 5.7851 | 5.4213 | 7.4605 | 4.8073 | 4.8027 | 4.6636 | |

| Entertainment | 1-Hamming | 0.8842 | 0.9128 | 0.9014 | 0.9066 | 0.9018 | 0.9048 | 0.9034 | 0.8940 | 0.8950 | 0.9264 | 0.9276 | 0.9281 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8074 | 0.8257 | 0.8035 | 0.7954 | 0.8158 | 0.8114 | 0.8006 | 0.8350 | 0.7223 | 0.8536 | 0.8561 | 0.8613 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.4078 | 0.4505 | 0.4243 | 0.3997 | 0.4339 | 0.4282 | 0.4317 | 0.4799 | 0.2764 | 0.5205 | 0.5252 | 0.5391 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.2351 | 0.2723 | 0.2646 | 0.2271 | 0.2539 | 0.2517 | 0.2772 | 0.3172 | 0.1156 | 0.3659 | 0.3677 | 0.3852 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1229 | 0.1096 | 0.1201 | 0.0946 | 0.1155 | 0.1110 | 0.1286 | 0.1622 | 0.0541 | 0.1364 | 0.1400 | 0.1481 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.2315 | 0.2208 | 0.2269 | 0.1707 | 0.2201 | 0.2073 | 0.2332 | 0.2991 | 0.0992 | 0.2692 | 0.2811 | 0.2873 | |

| Coverage | 4.6959 | 4.3235 | 4.8199 | 4.9384 | 4.5388 | 4.6301 | 4.8987 | 4.1561 | 6.4181 | 3.7775 | 3.6975 | 3.6377 | |

| Health | 1-Hamming | 0.9255 | 0.9382 | 0.9348 | 0.9374 | 0.9371 | 0.9425 | 0.9339 | 0.9318 | 0.9210 | 0.9497 | 0.9504 | 0.9515 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8983 | 0.9021 | 0.8852 | 0.8866 | 0.8935 | 0.8973 | 0.8973 | 0.9039 | 0.8496 | 0.9170 | 0.9223 | 0.9261 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.4939 | 0.4986 | 0.4815 | 0.4657 | 0.5072 | 0.5276 | 0.5068 | 0.5392 | 0.3579 | 0.6000 | 0.6247 | 0.6384 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.3354 | 0.3335 | 0.3355 | 0.2999 | 0.3644 | 0.3856 | 0.3597 | 0.4057 | 0.1973 | 0.4786 | 0.5163 | 0.5324 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0757 | 0.0777 | 0.0805 | 0.0608 | 0.0909 | 0.0682 | 0.0903 | 0.1173 | 0.0507 | 0.0663 | 0.1169 | 0.1209 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.3302 | 0.2560 | 0.2713 | 0.2216 | 0.3075 | 0.2797 | 0.3004 | 0.3659 | 0.1679 | 0.3076 | 0.4056 | 0.4101 | |

| Coverage | 4.5247 | 4.3600 | 5.0515 | 4.9723 | 4.7303 | 4.6881 | 4.6544 | 4.3671 | 6.2485 | 3.9497 | 3.7576 | 3.6298 | |

| Recreation | 1-Hamming | 0.8666 | 0.9113 | 0.9003 | 0.8980 | 0.8992 | 0.8996 | 0.8967 | 0.8879 | 0.8947 | 0.9308 | 0.9292 | 0.9296 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.7323 | 0.7315 | 0.7471 | 0.7254 | 0.7513 | 0.7551 | 0.7255 | 0.7612 | 0.6571 | 0.7690 | 0.7930 | 0.7985 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.3211 | 0.3385 | 0.3491 | 0.3102 | 0.3549 | 0.3556 | 0.3198 | 0.3834 | 0.2170 | 0.3860 | 0.4409 | 0.4504 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.1591 | 0.1937 | 0.1900 | 0.1530 | 0.1911 | 0.1831 | 0.1677 | 0.2318 | 0.0722 | 0.2265 | 0.2929 | 0.3019 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0978 | 0.0910 | 0.1002 | 0.0827 | 0.1017 | 0.0926 | 0.0937 | 0.1294 | 0.0415 | 0.0556 | 0.1205 | 0.1306 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.1592 | 0.1494 | 0.1669 | 0.1279 | 0.1651 | 0.1594 | 0.1456 | 0.2097 | 0.0614 | 0.1038 | 0.1985 | 0.2024 | |

| Coverage | 6.6750 | 6.6650 | 6.2568 | 6.7424 | 6.1543 | 6.0911 | 6.7627 | 6.0317 | 8.2247 | 5.8306 | 5.3058 | 5.1896 | |

| Reference | 1-Hamming | 0.9506 | 0.9552 | 0.9490 | 0.9569 | 0.9497 | 0.9522 | 0.9553 | 0.9542 | 0.9440 | 0.9642 | 0.9624 | 0.9634 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8820 | 0.8771 | 0.8718 | 0.8743 | 0.8752 | 0.8755 | 0.8819 | 0.8844 | 0.8167 | 0.8901 | 0.8931 | 0.8983 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.4854 | 0.4690 | 0.4441 | 0.4649 | 0.4567 | 0.4704 | 0.4958 | 0.5178 | 0.2841 | 0.5587 | 0.5582 | 0.5777 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.3265 | 0.2874 | 0.2727 | 0.3032 | 0.2723 | 0.3007 | 0.3487 | 0.3791 | 0.0814 | 0.4575 | 0.4373 | 0.4644 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0514 | 0.0664 | 0.0692 | 0.0535 | 0.0715 | 0.0699 | 0.0686 | 0.0843 | 0.0260 | 0.0187 | 0.0687 | 0.0708 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.2841 | 0.2617 | 0.2646 | 0.2581 | 0.2681 | 0.2880 | 0.2923 | 0.3435 | 0.0670 | 0.1944 | 0.3628 | 0.3611 | |

| Coverage | 4.3486 | 4.4905 | 4.6713 | 4.5809 | 4.5738 | 4.5717 | 4.3426 | 4.2757 | 6.4441 | 4.0926 | 3.9917 | 3.8267 | |

| Science | 1-Hamming | 0.9407 | 0.9502 | 0.9446 | 0.9473 | 0.9435 | 0.9454 | 0.9471 | 0.9424 | 0.9430 | 0.9608 | 0.9593 | 0.9596 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8184 | 0.8148 | 0.8133 | 0.7991 | 0.8097 | 0.8177 | 0.8190 | 0.8278 | 0.7734 | 0.8267 | 0.8399 | 0.8449 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.3115 | 0.3296 | 0.3122 | 0.2764 | 0.3050 | 0.3158 | 0.3395 | 0.3615 | 0.2110 | 0.3482 | 0.3995 | 0.4079 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.1582 | 0.1865 | 0.1603 | 0.1282 | 0.1572 | 0.1595 | 0.2028 | 0.2231 | 0.0723 | 0.1987 | 0.2642 | 0.2711 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0624 | 0.0612 | 0.0623 | 0.0439 | 0.0597 | 0.0548 | 0.0741 | 0.0809 | 0.0293 | 0.0154 | 0.0698 | 0.0744 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.1361 | 0.1463 | 0.1399 | 0.0908 | 0.1369 | 0.1298 | 0.1654 | 0.1913 | 0.0549 | 0.0510 | 0.1742 | 0.1684 | |

| Coverage | 8.6813 | 8.9410 | 8.9608 | 9.4447 | 9.0948 | 8.7677 | 8.7534 | 8.4367 | 10.5584 | 8.5153 | 7.9343 | 7.7084 | |

| Social | 1-Hamming | 0.9576 | 0.9625 | 0.9586 | 0.9595 | 0.9574 | 0.9600 | 0.9618 | 0.9621 | 0.9477 | 0.9669 | 0.9662 | 0.9666 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8881 | 0.8962 | 0.8953 | 0.8922 | 0.8916 | 0.8995 | 0.9019 | 0.9023 | 0.8515 | 0.9161 | 0.9122 | 0.9139 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.4738 | 0.5121 | 0.5025 | 0.4670 | 0.4920 | 0.5099 | 0.5499 | 0.5599 | 0.3196 | 0.5864 | 0.5901 | 0.5941 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.2931 | 0.3613 | 0.3455 | 0.2813 | 0.3327 | 0.3433 | 0.4114 | 0.4234 | 0.1405 | 0.4222 | 0.4571 | 0.4574 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0477 | 0.0536 | 0.0714 | 0.0483 | 0.0690 | 0.0693 | 0.0751 | 0.0700 | 0.0370 | 0.0033 | 0.0669 | 0.0756 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.1925 | 0.3129 | 0.3026 | 0.1769 | 0.3024 | 0.2921 | 0.3483 | 0.3688 | 0.1255 | 0.0430 | 0.3677 | 0.3565 | |

| Coverage | 5.2518 | 4.9009 | 4.9235 | 5.1183 | 5.1223 | 4.8134 | 4.7232 | 4.7222 | 6.6941 | 4.2353 | 4.3230 | 4.2311 | |

| Society | 1-Hamming | 0.8835 | 0.9230 | 0.9041 | 0.9062 | 0.9053 | 0.9107 | 0.9079 | 0.8917 | 0.9036 | 0.9357 | 0.9362 | 0.9367 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.7931 | 0.7954 | 0.7831 | 0.7799 | 0.7989 | 0.8015 | 0.7960 | 0.8012 | 0.7219 | 0.8283 | 0.8359 | 0.8366 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.3702 | 0.4058 | 0.3572 | 0.3443 | 0.3712 | 0.3804 | 0.3821 | 0.4221 | 0.2407 | 0.5111 | 0.5242 | 0.5291 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.2221 | 0.2254 | 0.1943 | 0.1856 | 0.1954 | 0.2100 | 0.2317 | 0.3023 | 0.0804 | 0.4251 | 0.4361 | 0.4454 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0944 | 0.0724 | 0.0833 | 0.0754 | 0.0858 | 0.0821 | 0.0943 | 0.1098 | 0.0428 | 0.0573 | 0.0817 | 0.0827 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.2009 | 0.1766 | 0.1705 | 0.1639 | 0.1722 | 0.1814 | 0.1969 | 0.2515 | 0.0769 | 0.2760 | 0.2790 | 0.2942 | |

| Coverage | 7.1623 | 7.1745 | 7.5051 | 7.6289 | 7.0188 | 7.0651 | 7.2065 | 7.0054 | 9.0593 | 6.3846 | 6.2447 | 6.1403 |

| Dataset | Metrics | CCA | wMLDAb | wMLDAe | wMLDAc | wMLDAf | wMLDAd | MLDA-LC | MDDM | SSMLDR | SMDRdm | NMLSDR | SMDR-IC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotions | 1-Hamming | 0.7482 | 0.7618 | 0.7490 | 0.7506 | 0.7701 | 0.7434 | 0.7656 | 0.7538 | 0.7529 | 0.7696 | 0.7732 | 0.7862 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.7600 | 0.7900 | 0.7674 | 0.7764 | 0.7894 | 0.7650 | 0.7946 | 0.7787 | 0.7750 | 0.7931 | 0.8029 | 0.8206 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.7191 | 0.7544 | 0.7368 | 0.7399 | 0.7535 | 0.7286 | 0.7596 | 0.7467 | 0.7397 | 0.7561 | 0.7677 | 0.7836 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.5989 | 0.6545 | 0.6455 | 0.6281 | 0.6545 | 0.6096 | 0.6573 | 0.6410 | 0.6376 | 0.6511 | 0.6736 | 0.6972 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.5560 | 0.5513 | 0.5606 | 0.5489 | 0.5888 | 0.5511 | 0.5727 | 0.5730 | 0.5588 | 0.5972 | 0.5914 | 0.6080 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.5706 | 0.5748 | 0.5722 | 0.5641 | 0.6039 | 0.5612 | 0.5966 | 0.5804 | 0.5728 | 0.6091 | 0.6121 | 0.6319 | |

| Coverage | 2.1242 | 2.0140 | 2.1511 | 2.0607 | 2.0045 | 2.1343 | 1.9792 | 2.0989 | 2.0820 | 1.9826 | 1.9511 | 1.8753 | |

| Scene | 1-Hamming | 0.8636 | 0.8713 | 0.8683 | 0.8701 | 0.8705 | 0.8721 | 0.8647 | 0.8677 | 0.8688 | 0.8890 | 0.8932 | 0.8934 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8386 | 0.8397 | 0.8422 | 0.8484 | 0.8433 | 0.8465 | 0.8421 | 0.8463 | 0.8461 | 0.8819 | 0.8890 | 0.8913 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.7616 | 0.7688 | 0.7685 | 0.7741 | 0.7726 | 0.7777 | 0.7606 | 0.7715 | 0.7731 | 0.8143 | 0.8226 | 0.8267 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.6231 | 0.6391 | 0.6355 | 0.6422 | 0.6438 | 0.6531 | 0.6177 | 0.6378 | 0.6409 | 0.7003 | 0.7111 | 0.7173 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.6056 | 0.6149 | 0.6188 | 0.6252 | 0.6252 | 0.6354 | 0.5969 | 0.6258 | 0.6250 | 0.6770 | 0.6863 | 0.6893 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.5995 | 0.6093 | 0.6130 | 0.6174 | 0.6173 | 0.6292 | 0.5903 | 0.6168 | 0.6170 | 0.6697 | 0.6797 | 0.6836 | |

| Coverage | 0.8953 | 0.8924 | 0.8769 | 0.8474 | 0.8758 | 0.8600 | 0.8703 | 0.8567 | 0.8566 | 0.6794 | 0.6443 | 0.6328 | |

| Corel5k | 1-Hamming | 0.9904 | 0.9904 | 0.9904 | 0.9905 | 0.9904 | 0.9905 | 0.9905 | 0.9905 | 0.9905 | 0.9905 | 0.9905 | 0.9906 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8574 | 0.8600 | 0.8603 | 0.8576 | 0.8587 | 0.8577 | 0.8570 | 0.8575 | 0.8575 | 0.8581 | 0.8568 | 0.8609 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.2213 | 0.2354 | 0.2316 | 0.2225 | 0.2293 | 0.2304 | 0.2301 | 0.2283 | 0.2197 | 0.2305 | 0.2263 | 0.2403 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.2247 | 0.2511 | 0.2375 | 0.2174 | 0.2346 | 0.2404 | 0.2365 | 0.2366 | 0.2182 | 0.2444 | 0.2389 | 0.2577 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0060 | 0.0096 | 0.0077 | 0.0056 | 0.0078 | 0.0077 | 0.0082 | 0.0049 | 0.0032 | 0.0035 | 0.0037 | 0.0055 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.0234 | 0.0431 | 0.0314 | 0.0205 | 0.0311 | 0.0277 | 0.0357 | 0.0195 | 0.0114 | 0.0128 | 0.0166 | 0.0236 | |

| Coverage | 119.3953 | 118.0986 | 117.7031 | 119.2533 | 119.0181 | 119.0487 | 120.1382 | 119.3591 | 119.7709 | 120.0287 | 121.4830 | 117.9619 | |

| Yeast | 1-Hamming | 0.7816 | 0.7855 | 0.7849 | 0.7851 | 0.7874 | 0.7864 | 0.7877 | 0.7903 | 0.7816 | 0.7847 | 0.7930 | 0.7943 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8042 | 0.8060 | 0.8075 | 0.8066 | 0.8070 | 0.8100 | 0.8079 | 0.8107 | 0.8040 | 0.8031 | 0.8138 | 0.8172 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.7304 | 0.7306 | 0.7354 | 0.7340 | 0.7358 | 0.7383 | 0.7332 | 0.7374 | 0.7297 | 0.7303 | 0.7457 | 0.7494 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.7273 | 0.7409 | 0.7405 | 0.7346 | 0.7372 | 0.7382 | 0.7354 | 0.7287 | 0.7457 | 0.7387 | 0.7507 | 0.7576 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.3484 | 0.2839 | 0.3436 | 0.3373 | 0.3360 | 0.3491 | 0.3191 | 0.3569 | 0.3041 | 0.3123 | 0.3549 | 0.3455 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.6037 | 0.5811 | 0.6088 | 0.6029 | 0.6049 | 0.6109 | 0.6074 | 0.6191 | 0.5922 | 0.6002 | 0.6219 | 0.6181 | |

| Coverage | 6.8034 | 6.7618 | 6.7270 | 6.7398 | 6.7404 | 6.6576 | 6.7361 | 6.6698 | 6.7809 | 6.7990 | 6.6229 | 6.6229 | |

| Arts | 1-Hamming | 0.9289 | 0.9359 | 0.9315 | 0.9314 | 0.9329 | 0.9328 | 0.9313 | 0.9286 | 0.9302 | 0.9362 | 0.9360 | 0.9374 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8374 | 0.8445 | 0.8412 | 0.8410 | 0.8412 | 0.8433 | 0.8402 | 0.8386 | 0.8349 | 0.8428 | 0.8442 | 0.8487 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.4915 | 0.5069 | 0.4999 | 0.4943 | 0.5018 | 0.5007 | 0.4905 | 0.4914 | 0.4790 | 0.4890 | 0.5026 | 0.5166 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.3715 | 0.3868 | 0.3808 | 0.3707 | 0.3861 | 0.3817 | 0.3674 | 0.3680 | 0.3531 | 0.3575 | 0.3843 | 0.4026 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1776 | 0.1473 | 0.1894 | 0.1759 | 0.1805 | 0.1871 | 0.1763 | 0.1768 | 0.1611 | 0.1435 | 0.1620 | 0.1720 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.2720 | 0.2504 | 0.2831 | 0.2693 | 0.2824 | 0.2769 | 0.2617 | 0.2772 | 0.2486 | 0.2195 | 0.2551 | 0.2708 | |

| Coverage | 5.7281 | 5.5627 | 5.6451 | 5.6321 | 5.6505 | 5.5943 | 5.6675 | 5.6947 | 5.8493 | 5.6033 | 5.6139 | 5.4561 | |

| Business | 1-Hamming | 0.9684 | 0.9702 | 0.9685 | 0.9687 | 0.9691 | 0.9690 | 0.9688 | 0.9679 | 0.9658 | 0.9700 | 0.9708 | 0.9715 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.9585 | 0.9573 | 0.9589 | 0.9601 | 0.9591 | 0.9581 | 0.9596 | 0.9583 | 0.9552 | 0.9545 | 0.9602 | 0.9618 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.8636 | 0.8636 | 0.8597 | 0.8611 | 0.8626 | 0.8595 | 0.8587 | 0.8584 | 0.8435 | 0.8588 | 0.8690 | 0.8768 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.8625 | 0.8584 | 0.8535 | 0.8551 | 0.8576 | 0.8569 | 0.8531 | 0.8535 | 0.8332 | 0.8625 | 0.8668 | 0.8784 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1669 | 0.1166 | 0.1513 | 0.1533 | 0.1626 | 0.1551 | 0.1559 | 0.1698 | 0.1331 | 0.0744 | 0.1469 | 0.1545 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.6785 | 0.6654 | 0.6699 | 0.6714 | 0.6781 | 0.6733 | 0.6707 | 0.6753 | 0.6481 | 0.6655 | 0.6916 | 0.6951 | |

| Coverage | 2.3756 | 2.3873 | 2.3371 | 2.3068 | 2.3437 | 2.4153 | 2.3275 | 2.3466 | 2.4845 | 2.5111 | 2.2897 | 2.2537 | |

| Computers | 1-Hamming | 0.9496 | 0.9557 | 0.9525 | 0.9528 | 0.9520 | 0.9546 | 0.9513 | 0.9476 | 0.9461 | 0.9551 | 0.9584 | 0.9590 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.9011 | 0.8975 | 0.9007 | 0.8999 | 0.8986 | 0.9031 | 0.9009 | 0.8975 | 0.8875 | 0.8976 | 0.9111 | 0.9149 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.5894 | 0.5951 | 0.5866 | 0.5838 | 0.5827 | 0.5916 | 0.5831 | 0.5840 | 0.5437 | 0.5949 | 0.6370 | 0.6433 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.4823 | 0.5012 | 0.4843 | 0.4750 | 0.4809 | 0.4869 | 0.4799 | 0.4862 | 0.4305 | 0.5065 | 0.5573 | 0.5622 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1405 | 0.0947 | 0.1450 | 0.1263 | 0.1392 | 0.1288 | 0.1345 | 0.1471 | 0.1136 | 0.0888 | 0.1454 | 0.1489 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.3872 | 0.3808 | 0.3948 | 0.3792 | 0.3981 | 0.3883 | 0.3848 | 0.3951 | 0.3409 | 0.3811 | 0.4423 | 0.4515 | |

| Coverage | 4.4657 | 4.6249 | 4.5040 | 4.5285 | 4.5744 | 4.4235 | 4.4881 | 4.5891 | 4.9771 | 4.6543 | 4.1604 | 4.0427 | |

| Education | 1-Hamming | 0.9496 | 0.9534 | 0.9511 | 0.9518 | 0.9516 | 0.9519 | 0.9513 | 0.9484 | 0.9498 | 0.9545 | 0.9547 | 0.9549 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8928 | 0.8971 | 0.8924 | 0.8923 | 0.8948 | 0.8940 | 0.8942 | 0.8910 | 0.8864 | 0.8967 | 0.8974 | 0.9006 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.4926 | 0.5025 | 0.5003 | 0.4940 | 0.5045 | 0.4964 | 0.4989 | 0.4923 | 0.4692 | 0.5024 | 0.5127 | 0.5225 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.3419 | 0.3485 | 0.3508 | 0.3439 | 0.3607 | 0.3421 | 0.3445 | 0.3427 | 0.3148 | 0.3482 | 0.3683 | 0.3764 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1102 | 0.0921 | 0.1178 | 0.1121 | 0.1159 | 0.1069 | 0.1154 | 0.1152 | 0.1009 | 0.1026 | 0.1060 | 0.1131 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.2736 | 0.2352 | 0.2735 | 0.2518 | 0.2679 | 0.2465 | 0.2492 | 0.2802 | 0.2234 | 0.2287 | 0.2533 | 0.2510 | |

| Coverage | 4.4508 | 4.2894 | 4.4725 | 4.4939 | 4.4335 | 4.4177 | 4.4527 | 4.5197 | 4.6693 | 4.3086 | 4.3164 | 4.2052 | |

| Entertainment | 1-Hamming | 0.9218 | 0.9300 | 0.9244 | 0.9249 | 0.9244 | 0.9268 | 0.9266 | 0.9220 | 0.9204 | 0.9309 | 0.9334 | 0.9354 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8617 | 0.8686 | 0.8659 | 0.8643 | 0.8654 | 0.8658 | 0.8624 | 0.8643 | 0.8523 | 0.8686 | 0.8755 | 0.8799 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.5415 | 0.5604 | 0.5570 | 0.5535 | 0.5584 | 0.5568 | 0.5426 | 0.5557 | 0.5202 | 0.5625 | 0.5833 | 0.5932 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.3936 | 0.4192 | 0.4179 | 0.4107 | 0.4175 | 0.4109 | 0.3909 | 0.4159 | 0.3679 | 0.4143 | 0.4470 | 0.4577 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.2135 | 0.1687 | 0.2041 | 0.1946 | 0.2073 | 0.1920 | 0.1780 | 0.2228 | 0.1661 | 0.1716 | 0.2008 | 0.2146 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.3624 | 0.3250 | 0.3561 | 0.3342 | 0.3580 | 0.3323 | 0.3108 | 0.3815 | 0.2997 | 0.3110 | 0.3607 | 0.3742 | |

| Coverage | 3.5743 | 3.4669 | 3.5048 | 3.5779 | 3.5085 | 3.5465 | 3.5887 | 3.5519 | 3.7814 | 3.4638 | 3.3178 | 3.2151 | |

| Health | 1-Hamming | 0.9518 | 0.9549 | 0.9535 | 0.9530 | 0.9541 | 0.9546 | 0.9509 | 0.9508 | 0.9474 | 0.9537 | 0.9562 | 0.9570 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.9315 | 0.9329 | 0.9336 | 0.9319 | 0.9341 | 0.9310 | 0.9273 | 0.9320 | 0.9190 | 0.9325 | 0.9366 | 0.9382 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.6592 | 0.6684 | 0.6684 | 0.6589 | 0.6688 | 0.6632 | 0.6379 | 0.6617 | 0.6039 | 0.6567 | 0.6828 | 0.6910 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.5615 | 0.5741 | 0.5757 | 0.5666 | 0.5747 | 0.5677 | 0.5304 | 0.5641 | 0.4936 | 0.5529 | 0.5927 | 0.6071 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1885 | 0.1587 | 0.1993 | 0.2058 | 0.2125 | 0.1906 | 0.1761 | 0.1985 | 0.1550 | 0.1640 | 0.2072 | 0.2083 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.4699 | 0.4499 | 0.4832 | 0.4647 | 0.4885 | 0.4621 | 0.4381 | 0.4829 | 0.3993 | 0.4244 | 0.4805 | 0.4902 | |

| Coverage | 3.4239 | 3.3803 | 3.3655 | 3.4105 | 3.3380 | 3.4931 | 3.5839 | 3.4192 | 3.8311 | 3.4003 | 3.2523 | 3.2255 | |

| Recreation | 1-Hamming | 0.9200 | 0.9305 | 0.9263 | 0.9248 | 0.9272 | 0.9262 | 0.9253 | 0.9211 | 0.9235 | 0.9323 | 0.9342 | 0.9359 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8063 | 0.8131 | 0.8142 | 0.8131 | 0.8131 | 0.8134 | 0.8046 | 0.8094 | 0.8005 | 0.8043 | 0.8214 | 0.8286 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.4728 | 0.4896 | 0.4922 | 0.4813 | 0.4925 | 0.4887 | 0.4696 | 0.4766 | 0.4534 | 0.4572 | 0.5056 | 0.5204 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.3375 | 0.3583 | 0.3637 | 0.3462 | 0.3628 | 0.3553 | 0.3329 | 0.3401 | 0.3107 | 0.3096 | 0.3738 | 0.3917 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.2054 | 0.1811 | 0.2290 | 0.2053 | 0.2289 | 0.2141 | 0.2004 | 0.2088 | 0.1764 | 0.1454 | 0.2033 | 0.2135 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.2794 | 0.2692 | 0.3045 | 0.2830 | 0.3046 | 0.2939 | 0.2661 | 0.2848 | 0.2440 | 0.2044 | 0.2907 | 0.3020 | |

| Coverage | 5.0508 | 4.9122 | 4.8983 | 4.8867 | 4.8609 | 4.8680 | 5.0757 | 4.9829 | 5.1655 | 5.0915 | 4.6943 | 4.5397 | |

| Reference | 1-Hamming | 0.9554 | 0.9633 | 0.9582 | 0.9582 | 0.9582 | 0.9601 | 0.9584 | 0.9569 | 0.9522 | 0.9635 | 0.9654 | 0.9657 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8930 | 0.8966 | 0.8900 | 0.8871 | 0.8891 | 0.8900 | 0.8856 | 0.8962 | 0.8577 | 0.8956 | 0.9073 | 0.9106 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.5435 | 0.5608 | 0.5460 | 0.5326 | 0.5404 | 0.5412 | 0.5183 | 0.5575 | 0.4469 | 0.5651 | 0.6042 | 0.6154 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.4095 | 0.4266 | 0.4191 | 0.3993 | 0.4093 | 0.4136 | 0.3845 | 0.4319 | 0.3034 | 0.4539 | 0.4919 | 0.5069 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0940 | 0.0913 | 0.1072 | 0.0944 | 0.1049 | 0.1084 | 0.0798 | 0.1144 | 0.0790 | 0.0483 | 0.1175 | 0.1184 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.3650 | 0.3801 | 0.3684 | 0.3470 | 0.3649 | 0.3577 | 0.3294 | 0.3932 | 0.2542 | 0.3007 | 0.4137 | 0.4255 | |

| Coverage | 3.9714 | 3.8601 | 4.0810 | 4.1669 | 4.1009 | 4.0773 | 4.2263 | 3.8670 | 5.1050 | 3.9079 | 3.5004 | 3.3993 | |

| Science | 1-Hamming | 0.9499 | 0.9575 | 0.9533 | 0.9540 | 0.9535 | 0.9543 | 0.9540 | 0.9501 | 0.9523 | 0.9604 | 0.9614 | 0.9622 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8423 | 0.8459 | 0.8430 | 0.8381 | 0.8473 | 0.8498 | 0.8453 | 0.8471 | 0.8351 | 0.8443 | 0.8632 | 0.8650 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.3958 | 0.4074 | 0.4058 | 0.3965 | 0.4136 | 0.4106 | 0.3969 | 0.4122 | 0.3617 | 0.3913 | 0.4622 | 0.4695 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.2627 | 0.2712 | 0.2743 | 0.2662 | 0.2814 | 0.2738 | 0.2575 | 0.2801 | 0.2223 | 0.2436 | 0.3369 | 0.3480 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1173 | 0.0975 | 0.1139 | 0.1122 | 0.1212 | 0.1138 | 0.1105 | 0.1189 | 0.0899 | 0.0464 | 0.1359 | 0.1398 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.2207 | 0.1965 | 0.2200 | 0.2082 | 0.2276 | 0.2136 | 0.2009 | 0.2318 | 0.1711 | 0.1053 | 0.2603 | 0.2607 | |

| Coverage | 7.6821 | 7.6145 | 7.7165 | 7.8391 | 7.5111 | 7.5092 | 7.6200 | 7.5131 | 7.9943 | 7.6924 | 6.8843 | 6.8199 | |

| Social | 1-Hamming | 0.9532 | 0.9625 | 0.9581 | 0.9575 | 0.9568 | 0.9586 | 0.9494 | 0.9574 | 0.9470 | 0.9674 | 0.9683 | 0.9693 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8896 | 0.8979 | 0.8935 | 0.8898 | 0.8916 | 0.8962 | 0.8727 | 0.9063 | 0.8550 | 0.9185 | 0.9229 | 0.9265 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.4669 | 0.4896 | 0.4736 | 0.4522 | 0.4663 | 0.4741 | 0.3958 | 0.5503 | 0.3306 | 0.5955 | 0.6280 | 0.6354 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.3022 | 0.3227 | 0.3101 | 0.2775 | 0.2976 | 0.2990 | 0.2292 | 0.4079 | 0.1631 | 0.4370 | 0.5110 | 0.5137 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0779 | 0.0694 | 0.0928 | 0.0810 | 0.0968 | 0.0906 | 0.0591 | 0.1129 | 0.0518 | 0.0055 | 0.1302 | 0.1376 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.2298 | 0.2524 | 0.2511 | 0.2056 | 0.2390 | 0.2243 | 0.1938 | 0.3494 | 0.1256 | 0.0625 | 0.4381 | 0.4310 | |

| Coverage | 5.1089 | 4.8045 | 4.9903 | 5.1461 | 5.1065 | 4.8719 | 5.8120 | 4.5001 | 6.4971 | 4.0898 | 3.8369 | 3.6669 | |

| Society | 1-Hamming | 0.9220 | 0.9365 | 0.9299 | 0.9269 | 0.9272 | 0.9301 | 0.9288 | 0.9243 | 0.9260 | 0.9370 | 0.9392 | 0.9404 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8390 | 0.8431 | 0.8364 | 0.8347 | 0.8378 | 0.8417 | 0.8287 | 0.8375 | 0.8195 | 0.8432 | 0.8534 | 0.8594 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.5013 | 0.5336 | 0.5083 | 0.4945 | 0.5070 | 0.5104 | 0.4750 | 0.5104 | 0.4565 | 0.5361 | 0.5638 | 0.5761 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.3883 | 0.4289 | 0.4036 | 0.3850 | 0.3960 | 0.3989 | 0.3542 | 0.4084 | 0.3368 | 0.4507 | 0.4865 | 0.5048 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1398 | 0.1127 | 0.1461 | 0.1438 | 0.1472 | 0.1443 | 0.1051 | 0.1511 | 0.1091 | 0.0907 | 0.1298 | 0.1537 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.2973 | 0.2866 | 0.3059 | 0.2801 | 0.2956 | 0.2911 | 0.2507 | 0.3212 | 0.2273 | 0.2712 | 0.3373 | 0.3568 | |

| Coverage | 5.9990 | 5.8973 | 6.0695 | 6.1839 | 6.0735 | 5.9843 | 6.2853 | 5.9705 | 6.5285 | 5.9838 | 5.6912 | 5.5111 |

| Dataset | Metrics | CCA | wMLDAb | wMLDAe | wMLDAc | wMLDAf | wMLDAd | MLDA-LC | MDDM | SSMLDR | SMDRdm | NMLSDR | SMDR-IC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotions | 1-Hamming | 0.7615 | 0.7717 | 0.7672 | 0.7739 | 0.7767 | 0.7766 | 0.7671 | 0.7750 | 0.7728 | 0.7798 | 0.7855 | 0.7960 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.7848 | 0.7976 | 0.7962 | 0.7990 | 0.8015 | 0.8108 | 0.8029 | 0.7974 | 0.8021 | 0.8152 | 0.8159 | 0.8270 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.7458 | 0.7638 | 0.7630 | 0.7612 | 0.7642 | 0.7764 | 0.7690 | 0.7650 | 0.7672 | 0.7795 | 0.7770 | 0.7945 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.6360 | 0.6781 | 0.6736 | 0.6657 | 0.6713 | 0.6933 | 0.6831 | 0.6758 | 0.6736 | 0.6837 | 0.6871 | 0.7185 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.5785 | 0.5675 | 0.5876 | 0.6040 | 0.5968 | 0.5989 | 0.5862 | 0.6071 | 0.5980 | 0.6049 | 0.6059 | 0.6244 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.5926 | 0.5988 | 0.5982 | 0.6197 | 0.6119 | 0.6197 | 0.5978 | 0.6235 | 0.6159 | 0.6284 | 0.6262 | 0.6443 | |

| Coverage | 2.0264 | 1.9848 | 2.0073 | 1.9893 | 1.9208 | 1.9449 | 1.9758 | 2.0090 | 1.9663 | 1.8775 | 1.8725 | 1.8281 | |

| Scene | 1-Hamming | 0.8828 | 0.8854 | 0.8834 | 0.8835 | 0.8868 | 0.8877 | 0.8740 | 0.8821 | 0.8849 | 0.8918 | 0.8918 | 0.8987 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8667 | 0.8700 | 0.8728 | 0.8694 | 0.8756 | 0.8765 | 0.8646 | 0.8705 | 0.8711 | 0.8853 | 0.8864 | 0.8956 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.7987 | 0.8019 | 0.8031 | 0.8011 | 0.8097 | 0.8114 | 0.7868 | 0.8012 | 0.8030 | 0.8192 | 0.8220 | 0.8323 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.6799 | 0.6823 | 0.6841 | 0.6812 | 0.6964 | 0.6971 | 0.6513 | 0.6795 | 0.6849 | 0.7064 | 0.7120 | 0.7256 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.6649 | 0.6609 | 0.6692 | 0.6596 | 0.6714 | 0.6773 | 0.6309 | 0.6596 | 0.6684 | 0.6806 | 0.6859 | 0.7021 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.6565 | 0.6556 | 0.6597 | 0.6533 | 0.6641 | 0.6708 | 0.6223 | 0.6514 | 0.6599 | 0.6756 | 0.6806 | 0.6977 | |

| Coverage | 0.7560 | 0.7281 | 0.7268 | 0.7372 | 0.7131 | 0.7071 | 0.7703 | 0.7333 | 0.7317 | 0.6599 | 0.6614 | 0.6051 | |

| Corel5k | 1-Hamming | 0.9905 | 0.9905 | 0.9905 | 0.9905 | 0.9905 | 0.9905 | 0.9905 | 0.9905 | 0.9906 | 0.9906 | 0.9906 | 0.9906 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8614 | 0.8633 | 0.8622 | 0.8619 | 0.8600 | 0.8640 | 0.8623 | 0.8619 | 0.8609 | 0.8601 | 0.8606 | 0.8645 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.2359 | 0.2459 | 0.2398 | 0.2349 | 0.2342 | 0.2389 | 0.2401 | 0.2338 | 0.2303 | 0.2324 | 0.2346 | 0.2457 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.2539 | 0.2702 | 0.2538 | 0.2439 | 0.2442 | 0.2519 | 0.2546 | 0.2428 | 0.2400 | 0.2505 | 0.2539 | 0.2694 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.0067 | 0.0111 | 0.0085 | 0.0067 | 0.0080 | 0.0079 | 0.0091 | 0.0065 | 0.0056 | 0.0041 | 0.0062 | 0.0088 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.0267 | 0.0449 | 0.0344 | 0.0232 | 0.0289 | 0.0277 | 0.0340 | 0.0267 | 0.0192 | 0.0185 | 0.0254 | 0.0334 | |

| Coverage | 117.6995 | 116.8086 | 116.7635 | 117.3177 | 118.7547 | 116.2923 | 117.1544 | 117.0889 | 117.6433 | 117.9017 | 118.3098 | 115.5051 | |

| Yeast | 1-Hamming | 0.7934 | 0.7856 | 0.7905 | 0.7876 | 0.7891 | 0.7918 | 0.7884 | 0.7938 | 0.7875 | 0.7907 | 0.7908 | 0.7963 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8168 | 0.8095 | 0.8136 | 0.8092 | 0.8083 | 0.8147 | 0.8107 | 0.8171 | 0.8107 | 0.8147 | 0.8131 | 0.8193 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.7452 | 0.7404 | 0.7439 | 0.7370 | 0.7375 | 0.7434 | 0.7411 | 0.7471 | 0.7407 | 0.7460 | 0.7420 | 0.7501 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.7489 | 0.7581 | 0.7541 | 0.7435 | 0.7404 | 0.7441 | 0.7523 | 0.7507 | 0.7539 | 0.7544 | 0.7508 | 0.7581 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.3499 | 0.2916 | 0.3459 | 0.3421 | 0.3526 | 0.3627 | 0.3347 | 0.3692 | 0.3154 | 0.3276 | 0.3473 | 0.3519 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.6228 | 0.5881 | 0.6144 | 0.6121 | 0.6152 | 0.6241 | 0.6143 | 0.6327 | 0.6046 | 0.6155 | 0.6164 | 0.6249 | |

| Coverage | 6.5970 | 6.7419 | 6.6375 | 6.7021 | 6.7200 | 6.5906 | 6.7010 | 6.5565 | 6.6972 | 6.6850 | 6.6313 | 6.5409 | |

| Arts | 1-Hamming | 0.9350 | 0.9383 | 0.9365 | 0.9361 | 0.9378 | 0.9362 | 0.9360 | 0.9353 | 0.9349 | 0.9371 | 0.9377 | 0.9391 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8486 | 0.8526 | 0.8533 | 0.8532 | 0.8550 | 0.8532 | 0.8525 | 0.8484 | 0.8475 | 0.8503 | 0.8523 | 0.8565 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.5167 | 0.5281 | 0.5271 | 0.5221 | 0.5318 | 0.5228 | 0.5217 | 0.5169 | 0.5074 | 0.5161 | 0.5224 | 0.5354 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.4010 | 0.4196 | 0.4113 | 0.4041 | 0.4188 | 0.4019 | 0.4035 | 0.3996 | 0.3871 | 0.3975 | 0.4056 | 0.4243 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.2003 | 0.1616 | 0.1926 | 0.1857 | 0.1975 | 0.1992 | 0.1948 | 0.1930 | 0.1741 | 0.1698 | 0.1764 | 0.1966 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.2950 | 0.2643 | 0.2962 | 0.2763 | 0.3019 | 0.2861 | 0.2781 | 0.2900 | 0.2606 | 0.2595 | 0.2734 | 0.2929 | |

| Coverage | 5.4450 | 5.3883 | 5.3297 | 5.3475 | 5.2751 | 5.3153 | 5.3294 | 5.4547 | 5.5149 | 5.4222 | 5.3745 | 5.2227 | |

| Business | 1-Hamming | 0.9710 | 0.9711 | 0.9708 | 0.9711 | 0.9709 | 0.9715 | 0.9703 | 0.9706 | 0.9699 | 0.9703 | 0.9712 | 0.9722 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.9624 | 0.9608 | 0.9622 | 0.9625 | 0.9627 | 0.9622 | 0.9626 | 0.9624 | 0.9612 | 0.9547 | 0.9622 | 0.9642 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.8738 | 0.8712 | 0.8747 | 0.8732 | 0.8743 | 0.8744 | 0.8712 | 0.8716 | 0.8647 | 0.8595 | 0.8747 | 0.8815 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.8732 | 0.8659 | 0.8727 | 0.8714 | 0.8709 | 0.8723 | 0.8685 | 0.8671 | 0.8588 | 0.8591 | 0.8709 | 0.8817 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1818 | 0.1347 | 0.1743 | 0.1775 | 0.1843 | 0.1865 | 0.1885 | 0.1882 | 0.1697 | 0.0868 | 0.1769 | 0.1923 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.6949 | 0.6792 | 0.6885 | 0.6923 | 0.6922 | 0.6947 | 0.6869 | 0.6931 | 0.6845 | 0.6692 | 0.6974 | 0.7041 | |

| Coverage | 2.2193 | 2.2740 | 2.2101 | 2.2083 | 2.2249 | 2.2060 | 2.2209 | 2.1829 | 2.2706 | 2.4765 | 2.2114 | 2.1547 | |

| Computers | 1-Hamming | 0.9559 | 0.9593 | 0.9572 | 0.9581 | 0.9577 | 0.9584 | 0.9571 | 0.9535 | 0.9533 | 0.9553 | 0.9586 | 0.9601 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.9120 | 0.9097 | 0.9132 | 0.9144 | 0.9142 | 0.9144 | 0.9130 | 0.9105 | 0.9059 | 0.9012 | 0.9153 | 0.9172 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.6345 | 0.6372 | 0.6374 | 0.6369 | 0.6402 | 0.6381 | 0.6338 | 0.6311 | 0.6056 | 0.6014 | 0.6442 | 0.6573 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.5491 | 0.5581 | 0.5497 | 0.5505 | 0.5519 | 0.5499 | 0.5473 | 0.5442 | 0.5104 | 0.5105 | 0.5604 | 0.5812 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1820 | 0.1285 | 0.1833 | 0.1762 | 0.1829 | 0.1711 | 0.1787 | 0.1855 | 0.1484 | 0.0903 | 0.1836 | 0.1802 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.4483 | 0.4373 | 0.4567 | 0.4488 | 0.4584 | 0.4395 | 0.4447 | 0.4406 | 0.4077 | 0.3720 | 0.4557 | 0.4664 | |

| Coverage | 4.0848 | 4.1838 | 4.0196 | 4.0554 | 3.9999 | 4.0347 | 4.1099 | 4.1432 | 4.3229 | 4.5234 | 3.9919 | 3.9225 | |

| Education | 1-Hamming | 0.9544 | 0.9560 | 0.9553 | 0.9550 | 0.9554 | 0.9552 | 0.9554 | 0.9538 | 0.9536 | 0.9555 | 0.9555 | 0.9562 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.9002 | 0.9033 | 0.9015 | 0.9017 | 0.9024 | 0.9014 | 0.9034 | 0.8990 | 0.8936 | 0.9009 | 0.9030 | 0.9043 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.5250 | 0.5309 | 0.5318 | 0.5293 | 0.5329 | 0.5269 | 0.5289 | 0.5221 | 0.4952 | 0.5209 | 0.5310 | 0.5396 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.3829 | 0.3865 | 0.3899 | 0.3865 | 0.3923 | 0.3828 | 0.3823 | 0.3774 | 0.3401 | 0.3767 | 0.3881 | 0.4003 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1516 | 0.1352 | 0.1367 | 0.1478 | 0.1410 | 0.1469 | 0.1512 | 0.1441 | 0.1031 | 0.1222 | 0.1293 | 0.1405 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.2931 | 0.2624 | 0.2775 | 0.2747 | 0.2934 | 0.2773 | 0.2794 | 0.2854 | 0.2046 | 0.2376 | 0.2601 | 0.2824 | |

| Coverage | 4.1844 | 4.1046 | 4.1851 | 4.1538 | 4.1309 | 4.1618 | 4.0851 | 4.2623 | 4.4157 | 4.2077 | 4.1237 | 4.0771 | |

| Entertainment | 1-Hamming | 0.9330 | 0.9365 | 0.9321 | 0.9333 | 0.9341 | 0.9339 | 0.9333 | 0.9337 | 0.9321 | 0.9354 | 0.9370 | 0.9372 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8773 | 0.8824 | 0.8792 | 0.8791 | 0.8789 | 0.8817 | 0.8798 | 0.8776 | 0.8750 | 0.8785 | 0.8817 | 0.8856 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.5858 | 0.6029 | 0.5934 | 0.5950 | 0.5995 | 0.5991 | 0.5918 | 0.5904 | 0.5820 | 0.5921 | 0.6071 | 0.6127 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.4491 | 0.4735 | 0.4633 | 0.4649 | 0.4702 | 0.4652 | 0.4567 | 0.4561 | 0.4460 | 0.4571 | 0.4817 | 0.4854 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.2497 | 0.1954 | 0.2329 | 0.2333 | 0.2353 | 0.2272 | 0.2133 | 0.2555 | 0.2046 | 0.2162 | 0.2339 | 0.2436 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.4096 | 0.3729 | 0.3886 | 0.3903 | 0.3932 | 0.3827 | 0.3601 | 0.4177 | 0.3599 | 0.3742 | 0.3996 | 0.4026 | |

| Coverage | 3.2566 | 3.1881 | 3.2192 | 3.2511 | 3.2267 | 3.1751 | 3.2452 | 3.2677 | 3.3087 | 3.2189 | 3.2041 | 3.1018 | |

| Health | 1-Hamming | 0.9569 | 0.9585 | 0.9584 | 0.9578 | 0.9584 | 0.9583 | 0.9569 | 0.9572 | 0.9527 | 0.9558 | 0.9589 | 0.9593 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.9399 | 0.9395 | 0.9421 | 0.9410 | 0.9433 | 0.9414 | 0.9392 | 0.9409 | 0.9306 | 0.9376 | 0.9423 | 0.9437 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.6934 | 0.6998 | 0.7062 | 0.6986 | 0.7087 | 0.7035 | 0.6914 | 0.7007 | 0.6500 | 0.6780 | 0.7064 | 0.7113 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.6055 | 0.6193 | 0.6257 | 0.6143 | 0.6260 | 0.6240 | 0.6023 | 0.6179 | 0.5465 | 0.5829 | 0.6228 | 0.6297 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.2280 | 0.1851 | 0.2345 | 0.2344 | 0.2468 | 0.2330 | 0.2283 | 0.2315 | 0.1943 | 0.1965 | 0.2296 | 0.2312 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.5062 | 0.4938 | 0.5235 | 0.5155 | 0.5270 | 0.5075 | 0.4946 | 0.5241 | 0.4496 | 0.4607 | 0.5191 | 0.5130 | |

| Coverage | 3.1229 | 3.1503 | 3.0704 | 3.0901 | 3.0003 | 3.1112 | 3.1484 | 3.0863 | 3.4417 | 3.1992 | 3.0234 | 2.9960 | |

| Recreation | 1-Hamming | 0.9307 | 0.9371 | 0.9350 | 0.9342 | 0.9347 | 0.9346 | 0.9334 | 0.9317 | 0.9324 | 0.9344 | 0.9365 | 0.9386 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8266 | 0.8303 | 0.8343 | 0.8313 | 0.8349 | 0.8354 | 0.8281 | 0.8283 | 0.8199 | 0.8148 | 0.8320 | 0.8399 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.5186 | 0.5303 | 0.5350 | 0.5255 | 0.5375 | 0.5347 | 0.5154 | 0.5240 | 0.5059 | 0.4895 | 0.5301 | 0.5458 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.3942 | 0.4115 | 0.4121 | 0.3995 | 0.4146 | 0.4119 | 0.3859 | 0.3981 | 0.3731 | 0.3525 | 0.4083 | 0.4265 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.2497 | 0.2276 | 0.2629 | 0.2469 | 0.2597 | 0.2666 | 0.2385 | 0.2519 | 0.2067 | 0.1824 | 0.2476 | 0.2666 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.3229 | 0.3208 | 0.3391 | 0.3301 | 0.3435 | 0.3397 | 0.3052 | 0.3266 | 0.2923 | 0.2456 | 0.3259 | 0.3440 | |

| Coverage | 4.5768 | 4.5287 | 4.4223 | 4.4789 | 4.4233 | 4.4032 | 4.5629 | 4.5653 | 4.7635 | 4.8695 | 4.4791 | 4.2944 | |

| Reference | 1-Hamming | 0.9639 | 0.9662 | 0.9641 | 0.9647 | 0.9646 | 0.9649 | 0.9625 | 0.9630 | 0.9614 | 0.9644 | 0.9670 | 0.9670 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.9068 | 0.9094 | 0.9085 | 0.9084 | 0.9094 | 0.9065 | 0.8996 | 0.9102 | 0.8912 | 0.9022 | 0.9124 | 0.9143 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.6023 | 0.6148 | 0.6055 | 0.6099 | 0.6063 | 0.6025 | 0.5697 | 0.6080 | 0.5415 | 0.5829 | 0.6257 | 0.6284 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.4914 | 0.5056 | 0.4931 | 0.5025 | 0.4923 | 0.4911 | 0.4485 | 0.4933 | 0.4167 | 0.4705 | 0.5199 | 0.5254 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1287 | 0.1230 | 0.1352 | 0.1366 | 0.1389 | 0.1354 | 0.1141 | 0.1341 | 0.0910 | 0.0885 | 0.1366 | 0.1471 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.4359 | 0.4412 | 0.4359 | 0.4295 | 0.4351 | 0.4217 | 0.3852 | 0.4461 | 0.3536 | 0.3538 | 0.4475 | 0.4476 | |

| Coverage | 3.5143 | 3.4197 | 3.4615 | 3.4766 | 3.4141 | 3.5131 | 3.7654 | 3.4243 | 4.0247 | 3.6828 | 3.3325 | 3.2698 | |

| Science | 1-Hamming | 0.9590 | 0.9621 | 0.9604 | 0.9602 | 0.9604 | 0.9605 | 0.9596 | 0.9589 | 0.9592 | 0.9608 | 0.9628 | 0.9634 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8633 | 0.8627 | 0.8660 | 0.8657 | 0.8683 | 0.8686 | 0.8639 | 0.8634 | 0.8559 | 0.8477 | 0.8684 | 0.8735 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.4623 | 0.4653 | 0.4701 | 0.4652 | 0.4745 | 0.4742 | 0.4597 | 0.4660 | 0.4309 | 0.4121 | 0.4795 | 0.4910 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.3357 | 0.3423 | 0.3483 | 0.3401 | 0.3532 | 0.3489 | 0.3318 | 0.3437 | 0.2985 | 0.2787 | 0.3570 | 0.3723 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1590 | 0.1235 | 0.1639 | 0.1536 | 0.1518 | 0.1570 | 0.1479 | 0.1527 | 0.1228 | 0.0759 | 0.1450 | 0.1565 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.2702 | 0.2498 | 0.2812 | 0.2655 | 0.2811 | 0.2807 | 0.2616 | 0.2835 | 0.2211 | 0.1726 | 0.2773 | 0.2832 | |

| Coverage | 6.8751 | 6.9052 | 6.7387 | 6.7311 | 6.6656 | 6.6881 | 6.8797 | 6.8390 | 7.1929 | 7.5374 | 6.6781 | 6.4324 | |

| Social | 1-Hamming | 0.9625 | 0.9681 | 0.9653 | 0.9647 | 0.9654 | 0.9657 | 0.9623 | 0.9638 | 0.9582 | 0.9678 | 0.9691 | 0.9704 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.9160 | 0.9209 | 0.9191 | 0.9220 | 0.9208 | 0.9187 | 0.9101 | 0.9208 | 0.9007 | 0.9188 | 0.9281 | 0.9323 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.5849 | 0.6093 | 0.5964 | 0.5951 | 0.6004 | 0.5900 | 0.5598 | 0.6098 | 0.5072 | 0.5981 | 0.6489 | 0.6581 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.4491 | 0.4823 | 0.4649 | 0.4582 | 0.4673 | 0.4553 | 0.4207 | 0.4855 | 0.3547 | 0.4422 | 0.5368 | 0.5434 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1412 | 0.1151 | 0.1491 | 0.1517 | 0.1661 | 0.1469 | 0.1184 | 0.1543 | 0.1047 | 0.0080 | 0.1672 | 0.1622 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.3701 | 0.4069 | 0.3984 | 0.3816 | 0.4008 | 0.3794 | 0.3454 | 0.4147 | 0.2702 | 0.0885 | 0.4630 | 0.4661 | |

| Coverage | 4.0837 | 3.8727 | 3.9483 | 3.8166 | 3.8927 | 4.0121 | 4.2923 | 3.8763 | 4.6708 | 4.0424 | 3.5747 | 3.4423 | |

| Society | 1-Hamming | 0.9354 | 0.9413 | 0.9380 | 0.9365 | 0.9373 | 0.9375 | 0.9354 | 0.9356 | 0.9356 | 0.9394 | 0.9414 | 0.9421 |

| 1-Ranking | 0.8560 | 0.8584 | 0.8588 | 0.8554 | 0.8575 | 0.8584 | 0.8476 | 0.8560 | 0.8462 | 0.8530 | 0.8588 | 0.8628 | |

| AvgPrec | 0.5572 | 0.5787 | 0.5665 | 0.5548 | 0.5645 | 0.5636 | 0.5373 | 0.5597 | 0.5352 | 0.5584 | 0.5818 | 0.5898 | |

| 1-OneError | 0.4688 | 0.5003 | 0.4827 | 0.4694 | 0.4827 | 0.4795 | 0.4445 | 0.4741 | 0.4389 | 0.4784 | 0.5163 | 0.5269 | |

| MacroF1 | 0.1685 | 0.1376 | 0.1708 | 0.1633 | 0.1670 | 0.1705 | 0.1212 | 0.1682 | 0.1301 | 0.1175 | 0.1573 | 0.1682 | |

| MicroF1 | 0.3470 | 0.3278 | 0.3526 | 0.3321 | 0.3471 | 0.3446 | 0.2907 | 0.3533 | 0.3010 | 0.3121 | 0.3665 | 0.3681 | |

| Coverage | 5.5597 | 5.5129 | 5.4695 | 5.6288 | 5.5691 | 5.5561 | 5.8383 | 5.5596 | 5.8517 | 5.6550 | 5.5235 | 5.4241 |

| Metric | () | Critical Value () |

|---|---|---|

| Hamming loss | 1.8513 | |

| Ranking loss | ||

| Average Precision | ||

| One Error | ||

| MacroF1 | ||

| MicroF1 | ||

| Coverage |

| Dataset | CCA | wMLDAb | wMLDAe | wMLDAc | wMLDAf | wMLDAd | MLDA-LC | MDDM | SSMLDR | SMDRdm | NMLSDR | SMDR-IC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotions | 0.0662 | 0.0297 | 0.0201 | 0.0276 | 0.0302 | 0.0520 | 0.0206 | 0.0242 | 0.0422 | 0.0395 | 0.0361 | 0.1429 |

| Scene | 0.1193 | 0.1183 | 0.1203 | 0.1116 | 0.1224 | 0.1378 | 0.1697 | 0.1463 | 0.7838 | 0.7003 | 0.6598 | 0.8260 |

| Yeast | 0.1435 | 0.1469 | 0.1407 | 0.1503 | 0.1569 | 1.0397 | 0.1557 | 0.1405 | 0.7012 | 0.5310 | 0.4905 | 0.6690 |

| Arts | 0.5485 | 0.5748 | 0.5866 | 0.5789 | 1.1861 | 1.5268 | 0.9560 | 1.3994 | 6.1865 | 5.8123 | 5.2988 | 11.9221 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, R.; Du, J.; Ding, J.; Jia, L.; Chen, Y.; Shang, Z. Semi-Supervised Multi-Label Dimensionality Reduction Learning by Instance and Label Correlations. Mathematics 2023, 11, 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11030782

Li R, Du J, Ding J, Jia L, Chen Y, Shang Z. Semi-Supervised Multi-Label Dimensionality Reduction Learning by Instance and Label Correlations. Mathematics. 2023; 11(3):782. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11030782

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Runxin, Jiaxing Du, Jiaman Ding, Lianyin Jia, Yinong Chen, and Zhenhong Shang. 2023. "Semi-Supervised Multi-Label Dimensionality Reduction Learning by Instance and Label Correlations" Mathematics 11, no. 3: 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11030782

APA StyleLi, R., Du, J., Ding, J., Jia, L., Chen, Y., & Shang, Z. (2023). Semi-Supervised Multi-Label Dimensionality Reduction Learning by Instance and Label Correlations. Mathematics, 11(3), 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11030782