Abstract

The longest -path problem on supergrid graphs is known to be NP-complete. However, the complexity of this problem on supergrid graphs with or without holes is still unknown.In the past, we presented linear-time algorithms for solving the longest -path problem on L-shaped and C-shaped supergrid graphs, which form subclasses of supergrid graphs without holes. In this paper, we will determine the complexity of the longest -path problem on O-shaped supergrid graphs, which form a subclass of supergrid graphs with holes. These graphs are rectangular supergrid graphs with rectangular holes. It is worth noting that O-shaped supergrid graphs contain L-shaped and C-shaped supergrid graphs as subgraphs, but there is no inclusion relationship between them. We will propose a linear-time algorithm to solve the longest -path problem on O-shaped supergrid graphs. The longest -paths of O-shaped supergrid graphs have applications in calculating the minimum trace when printing hollow objects using computer embroidery machines and 3D printers.

Keywords:

longest path; Hamiltonian-connected; supergrid graphs; O-shaped supergrid graphs; computerized embroidery machines; 3D printers MSC:

05C38; 05C40; 05C85; 05C90; 68R10

1. Introduction

All graphs considered in this paper are undirected and simple. Let G be a graph. We denote the vertex set and the edge set of G by and , respectively. A Hamiltonian path (resp., cycle) on graph G is a simple path (resp., cycle) that visits every vertex of G exactly once. The Hamiltonian path (cycle) problem involves determining whether a graph has a Hamiltonian path (cycle). A Hamiltonian -path is a Hamiltonian path in a graph that starts from vertex s and ends at vertex t. A graph is Hamiltonian-connected if it contains a Hamiltonian -path for every two distinct vertices in the graph. The longest -path in a graph is the path from s to t that visits the most vertices. The longest -path problem on a graph involves determining whether the graph contains a Hamiltonian -path and finding the longest -path if it is not. The above problems are NP-complete for general graphs [1,2], as well as for various special graph classes, including undirected path graphs [3], circle graphs [4], split graphs [5], triangular grid graphs [6], supergrid graphs [7], bipartite graphs [8], grid graphs [9], and so on. Next, we will discuss the conditions under which a Hamiltonian -path does not exist. Let G be a connected graph and . We say that is a vertex cut if removing from G results in a disconnected graph. Moreover, a vertex is called a cut vertex if removing v from G makes it disconnected [10]. Let us consider that s is a cut vertex of G. Then, removing s from G results in some disjoint connected components. Since a Hamiltonian path from s to t must pass through all vertices of G exactly once and the path from s to other components must pass through s at least twice, a Hamiltonian -path does not exist. The same holds true for t. In addition, a Hamiltonian -path does not exist when is a vertex cut of G using similar arguments. Thus, if s or t is a cut vertex of G or if is a vertex cut of G, then graph G contains no Hamiltonian -path.

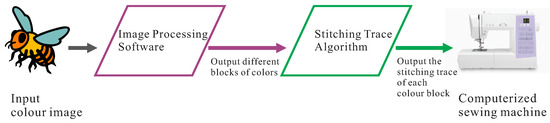

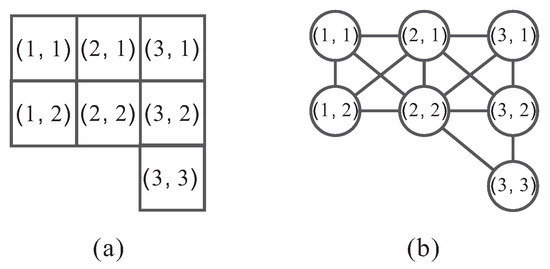

Supergrid graphs are proposed to solve the calculation of stitch paths on computer embroidery machines [7]. If we input a colored picture, computer image software first processes it into blocks of different colors; then, the stitch algorithm calculates each stitch path in every block and transfers it to the computerized embroidery machine for embroidery work. Figure 1 shows the operation flow of a computerized embroidery machine. The supergrid graph is mainly used in the calculation of the stitch path. Considering the operation of computer embroidery machines, each needle point is an integer coordinate, and its moving direction includes its eight directions: up, down, left, right, upper-left, upper-right, upper-left, and lower-left. We can express each needle point as a lattice, as shown in Figure 2a, and the eight adjacent lattices are the next possible positions where the needle point may move to, so we can represent the lattice as a vertex of the graph, and there are edge adjacencies among them. Figure 2b is a graph representation of Figure 2a. Then, the block generated by each image software is a supergrid graph. The supergrid graph is then defined as follows: each vertex v with integer coordinates is represented as , where and are the x- and y-coordinates of v, respectively. In the graphical representations in this paper, we use as the coordinates of the uppermost left vertex of a supergrid graph. For two vertices u and v of a supergrid graph, is an edge if and only if and . In other words, u is one of the following vertices: , , , , , , , or . Supergrid graphs include grid graphs and triangular grid graphs as subgraphs. Although they have an identical set of vertices, their edge sets are entirely distinct. Therefore, these graph classes do not belong to each other; that is, a supergrid graph is not necessary a grid graph or a triangular grid graph, and vice versa. Clearly, grid graphs are bipartite and planar [9], but triangular grid and supergrid graphs are not always bipartite or planar.

Figure 1.

The primary elements and operational sequence of a computerized embroidery procedure.

Figure 2.

(a) A collection of lattices and (b) the associated supergrid graph of (a), in which each lattice is represented as a vertex with integer coordinates.

The Hamilton path problem on supergrid graphs is known to be NP-complete [7]; hence, the longest -path problem is also NP-complete for supergrid graphs. However, these two problems for supergrid graphs with or without holes are still open. This paper proposes a linear-time algorithm to solve the longest -path problem on O-shaped supergrid graphs, which are a subclass of hollow supergrid graphs. A preliminary version of this paper has appeared in [11], and a preprint version of the paper has been posted on the arXiv system [12], an open platform for scholarly research exchange. The related research works are introduced as follows: Recently, Hamiltonian path (cycle) and Hamiltonian-connected problems for grid, triangular grid, and supergrid graphs have received much attention. Itai et al. [9] showed that Hamiltonian path and cycle problems for grid graphs are NP-complete and gave necessary and sufficient conditions for rectangular grid graphs to be Hamiltonian-connected. Zamfirescu et al. [13] provided sufficient conditions for a grid graph to have a Hamiltonian cycle and showed that all grid graphs of positive width have Hamiltonian line graphs. Chen et al. [14] improved the Hamiltonian path algorithm for rectangular grid graphs and presented a parallel algorithm for the Hamiltonian path problem with two given end vertices. Lenhart and Umans [15] showed that the Hamiltonian cycle problem on solid grid graphs can be solved in polynomial time. In addition to grid graphs, researchers have studied Hamiltonian cycle and path problems on triangular and hexagonal grid graphs, as well as alphabet grid graphs. Keshavarz-Kohjerdi and Bagheri [16] presented a linear-time algorithm for computing the longest -paths in L-shaped grid graphs. Recently, Nishat et al. [17] designed a linear-time algorithm to reconfigure any 1-complex Hamiltonian path to a canonical Hamiltonian path in rectangular grids. Supergrid graphs, a more complex type of graph, have also been studied. Hung et al. [7] proved that Hamiltonian cycle and path problems on supergrid graphs are NP-complete, while showing that every rectangular supergrid graph is Hamiltonian. In subsequent studies, researchers explored the complexities of Hamiltonian problems for special subclasses of supergrid graphs, such as linear-convex [18] and rectangular supergrid graphs [19]. In [20,21], we presented linear-time algorithms for solving the longest -path problem on L-shaped and C-shaped supergrid graphs, which form two subclasses of supergrid graphs without holes. In this paper, we study the Hamiltonian and longest -path problems for O-shaped supergrid graphs, which are rectangular supergrid graphs with rectangular holes. We prove that O-shaped supergrid graphs are always Hamiltonian and Hamiltonian-connected except for a few conditions and present a linear-time algorithm to compute the longest -path under these exceptional conditions. This study can be regarded as the first attempt to solve the Hamiltonian and longest -path problems on supergrid graphs with holes.

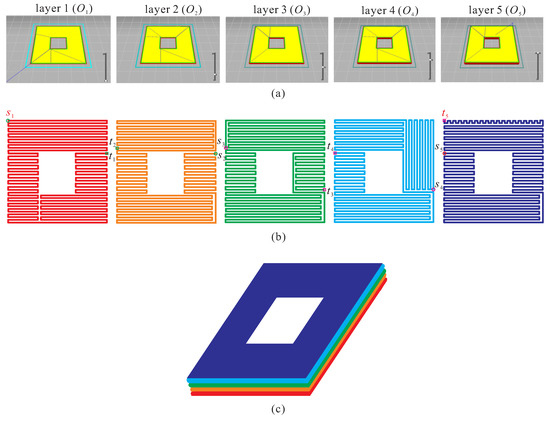

The Hamiltonian connectivity of O-shaped supergrid graphs can also be applied to compute the minimum trace of 3D printers as follows [11]: Let us consider a 3D printer with a hollow object (O-type object) being printed. The software produces a series of thin layers, designs a path for each layer, combines these paths of produced layers, and transmits the above paths to the 3D printer. Because 3D printing is performed layer by layer (see Figure 3a), each layer can be considered as an O-shaped supergrid graph. Let us suppose that there are k layers under the above 3D printing. If the Hamiltonian connectivity of O-shaped supergrid graphs holds true, then we can find a Hamiltonian -path of an O-shaped supergrid graph , where , , represents a layer under 3D printing. Thus, we can design an optimal trace for the above 3D printing, where is adjacent to for . In this application, we restrict the 3D printer nozzle to be located at integer coordinates. As an example, Figure 3a shows the five layers, –, of a 3D print for an O-type object, and Figure 3b depicts the Hamiltonian -paths of for ; the result of this 3D printing is shown in Figure 3c.

Figure 3.

(a) The five layers (–) of a 3D printing model for an O-type object, (b) the computation of the Hamiltonian -path for each layer shown in (a), and (c) the final result after completing the 5-layered 3D printing process.

The following is the organization of the paper: Section 2 introduces notations, observations, and previously established results, along with verification of the Hamiltonicity of O-shaped supergrid graphs. In Section 3, conditions are discovered that prohibit the existence of Hamiltonian -paths in O-shaped supergrid graphs. Section 4 presents that O-shaped supergrid graphs are Hamiltonian-connected except for the conditions mentioned in Section 3. An algorithm for computing the longest -paths of O-shaped supergrid graphs in linear time is described in Section 5. Finally, conclusions are provided in Section 6.

2. Notations and Background Results

This section introduces several terms and symbols, along with the presentation of some prior observations and established results related to the Hamiltonicity and Hamiltonian connectivity of rectangular supergrid graphs. For any graph-theoretic terminology that is not defined in this paper, please refer to [10].

Let G be a finite, undirected, and simple graph. Let and . The subgraph of G induced by S is denoted by , while the subgraph induced by is denoted by . We use to represent in general. If , we say that u is adjacent to v and that u and v are incident to edge . We use to indicate that u and v are adjacent and to indicate that they are not adjacent. An edge is adjoined by a vertex w if and . Two edges, and , are said to be parallel and are denoted by , if and . A vertex adjacent to vertex v is called a neighbor of v. The set of neighbors of v in G is denoted by , and the set of neighbors along with v itself is denoted by . The degree of vertex v in G, denoted by , is the number of vertices adjacent to v. A path P of length in G, denoted by , is an ordered sequence of vertices , such that for , and all vertices except in the sequence are distinct. The first and last vertices visited by P are denoted by and , respectively. We use to indicate that P visits vertex , and to represent that P visits edge . A path from to is denoted by -path. Additionally, we use P to refer to the set of vertices visited by path P if it is clear from the context. A cycle is a path C with and . Two paths (or cycles), and , in graph G are vertex disjoint if . If , then two vertex-disjoint paths and can be concatenated into a path, which is denoted by .

A two-dimensional supergrid, denoted by , is an infinite graph with vertices corresponding to all points (vertices) in the plane with integer coordinates. Two vertices in are adjacent if and only if the difference between their x- or y-coordinates is, at most, 1. A supergrid graph is a finite vertex-induced subgraph of . Each vertex v in a supergrid graph can be represented as , where and are the x- and y-coordinates of v, respectively. The set of possible adjacent vertices of a vertex in a supergrid graph includes , , , , , , , and . An edge is called horizontal (resp., vertical) if (resp., ), and it is said to be crossed if it is neither horizontal nor vertical. Next, we define some special supergrid graphs studied in the paper, as follows.

Definition 1.

Graph is a supergrid graph with vertex set consisting of all vertices of the form , with and . A supergrid graph is called a rectangular supergrid graph if it is isomorphic to for some positive integers m and n. When is considered, it is called an n-rectangle.

For , a rectangular supergrid graph contains four boundaries, each consisting of boundary edges. A path that visits all vertices and edges of a single boundary in and that has a length equal to the number of visited vertices is called a boundary path. A vertex in is called the upper-left (resp., upper-right, down-left, and down-right) corner, if for any vertex , , and (resp., and , and , and and ). In this paper, we assume that are the coordinates of the vertex in the upper-left corner in all figures, unless explicitly stated otherwise.

Definition 2.

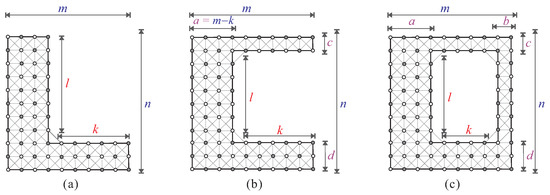

Let us suppose that is a rectangular supergrid graph. We define as the supergrid graph obtained from by removing the subgraph located in the upper-right corner with coordinates . An L-shaped supergrid graph is a supergrid graph isomorphic to (see Figure 4a).

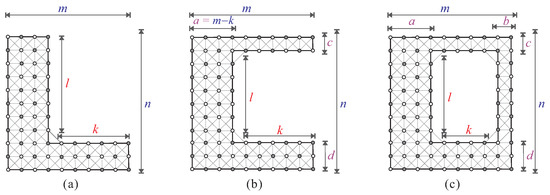

Figure 4.

The structures of three types of supergrid graphs: (a) L-shaped supergrid graph , (b) C-shaped supergrid graph , and (c) O-shaped supergrid graph .

Definition 3.

Let be a rectangular supergrid graph. We define a C-shaped supergrid graph as a subgraph of obtained by removing the subgraph located at the vertex with coordinates . Additionally, and must have exactly one border side in common, and we require that , , and (see Figure 4b).

Definition 4.

Let us consider a rectangular supergrid graph . An O-shaped supergrid graph is obtained by removing subgraph from vertex of . Graphs and do not share any border side. Parameters satisfy , , and (see Figure 4c).

When proving our results, it is necessary to partition a supergrid graph G into k disjoint parts, where . We define such an operation on G as follows.

Definition 5.

Let us consider a supergrid graph G. A separation operation on G is a partition of G into k vertex-disjoint supergrid subgraphs , , ⋯, , i.e., and for and , where . A separation is referred to as vertical if it comprises a set of horizontal edges and as horizontal if it comprises a set of vertical edges.

Let be a supergrid graph G with two distinct specified vertices s and t. We assume without loss of generality that for the remainder of the paper, unless we explicitly state otherwise. We denote a Hamiltonian path between s and t in G as . If a Hamiltonian -path exists in G, we say that exists. In the following, we present some previously established results.

Let be a rectangular supergrid graph with dimensions . Let us consider a cycle of , and let H be a boundary of , which is a subgraph of . We denote the restriction of to H by . If , i.e., is a boundary path on H, is referred to as a flat face on H. If and contains at least one boundary edge of H, then is called a concave face on H. A Hamiltonian cycle of is said to be canonical if it contains three flat faces on two shorter boundaries and one longer boundary, and one concave face on the other boundary, where the shorter boundary consists of three vertices. For or , a Hamiltonian cycle of is referred to as canonical if it contains three flat faces on three boundaries and one concave face on the other boundary. The following lemma shows the result from [7] that verifies the Hamiltonicity of rectangular supergrid graphs.

Lemma 1

(See [7]). The following statements are true for rectangular supergrid graph , where :

If , then has a Hamiltonian cycle that is canonical.

If or , contains four canonical Hamiltonian cycles, with each having a concave face on a different boundary.

In Section 1 and in [19], we verified that if s or t is a cut vertex of , or if is a vertex cut of , then does not exist. Thus, does not exist if the following condition is satisfied:

- (F1)

Figure 5. Rectangular supergrid graphs in which there is no Hamiltonian -path for (a) and (b) , where solid lines indicate the longest path between s and t.

Figure 5. Rectangular supergrid graphs in which there is no Hamiltonian -path for (a) and (b) , where solid lines indicate the longest path between s and t.

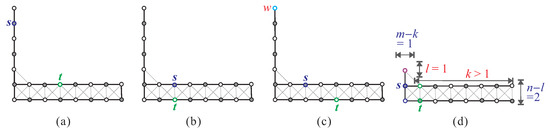

We demonstrated in [20] that in addition to condition (F1) (shown in Figure 6a,b), does not exist when any of the following conditions are satisfied.

Figure 6.

L-shaped supergrid graph does not contain a Hamiltonian -path when one of the following conditions are satisfied: (a) s is a cut vertex; (b) is a vertex cut; (c) there exists a vertex w such that , , and ; (d) , , , , and .

- (F2)

- (F3)

- , , , , and or (see Figure 6d).

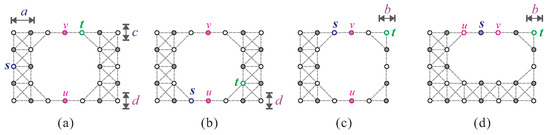

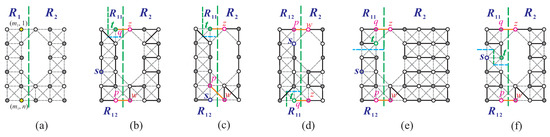

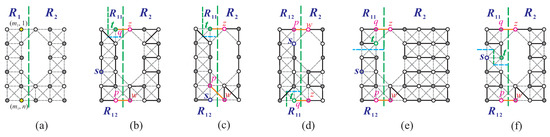

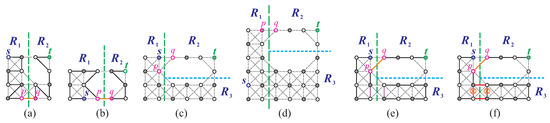

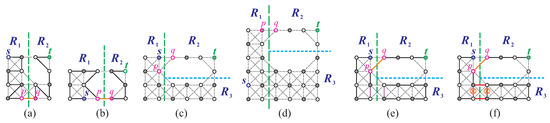

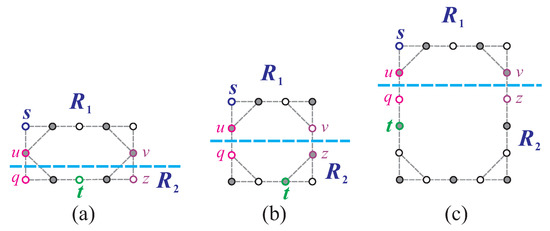

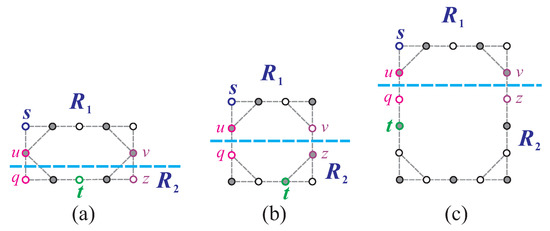

In addition to conditions (F1) and (F2) depicted in Figure 7a–c, respectively, we demonstrated in [21] that the existence of a Hamiltonian -path in is prohibited if satisfies any of the following conditions.

Figure 7.

C-shaped supergrid graphs in which there is no Hamiltonian -path, when one of the following conditions are satisfied: (a) s is a cut vertex; (b) is a vertex cut; (c) there exists a vertex w such that , , and ; (d) , , , and ; (e–g) condition (F5) holds; (h) and .

- (F4)

- , , and either of the following: , and or ; or , and or (see Figure 7d).

- (F5)

- , , and one the following:(1) , , and (see Figure 7e);(2) , , , and (see Figure 7f);(3) , , and (see Figure 7g).

- (F6)

- , and or (see Figure 7h).

Theorem 1

(See [19,20,21]). A Hamiltonian -path exists in a rectangular, L-shaped, or C-shaped supergrid graph G with vertices s and t, if and only if does not satisfy conditions –.

The Hamiltonian -path in that was constructed in [19] is known as the canonical path. This path satisfies the property that it contains at least one boundary edge from each boundary.

Lemma 2

(See [19]). If is a rectangular supergrid graph, such that , and s and t are two distinct vertices of , and if condition is not satisfied, then there exists a canonical Hamiltonian -path in , meaning that exists.

Assuming that does not satisfy condition (F1), we define three vertices , , and of with and . In [20], it was demonstrated that a Hamiltonian -path Q exists in with if the following condition (F7) is satisfied; otherwise, .

- (F7)

- and , or and .

The following lemma summarizes the previous results.

Lemma 3

(See [20]). Suppose that is a rectangular supergrid graph with and , and let s and t be two distinct vertices in . In addition, let , , and . If does not satisfy condition , then there exists a canonical Hamiltonian -path Q in such that if satisfies condition , and otherwise.

In [21], we derived the following lemma for a three-rectangle .

Lemma 4

(See [21]). Let s and t be two distinct vertices of , and let , , and be three other vertices of . Let us suppose that . Then, there exists a Hamiltonian -path of that contains both edges and .

The Hamiltonicities of L-shaped and C-shaped supergrid graphs were verified in [20,21] as follows.

Theorem 2

(See [20,21]). Let us consider (resp., ) as an L-shaped (resp., C-shaped) supergrid graph. It contains a Hamiltonian cycle if and only if it does not satisfy condition (resp., ), which is defined as follows:

- (F8)

- There exists a vertex w in such that .

- (F9)

- , or there exists a vertex satisfying .

The following propositions, which relate cycles, paths, and vertices, were presented in [7,18,19] and will be used in the proofs of our results.

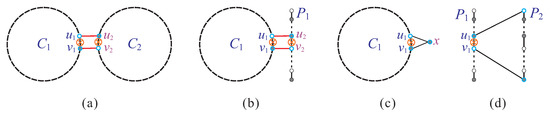

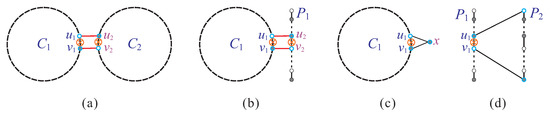

Proposition 1

(See [7,18,19]). Let and be two cycles in a graph G that do not share any vertices; let and be a cycle and a path in G, such that ; and let x be a vertex in or . The following statements hold true:

If there exist two edges and such that , then and can be combined into a cycle of G (see Figure 8a).

Figure 8.

Schematic diagrams of (a) Statement (1), (b) Statement (2), (c) Statement (3), and (d) Statement (4) of Proposition 1, where the cycles or paths are denoted by bold dashed lines, and the symbol ⊗ is used to signify the removal of an edge during their construction.

If there exist two edges and such that , then and can be combined into a path of G (see Figure 8b).

If vertex x adjoins an edge of (or ), then (or ) and x can be combined into a cycle (or path) of G (see Figure 8c).

If there exists an edge such that and , then and can be combined into a cycle C of G (see Figure 8d).

We demonstrated in [19,20,21] that the problem of finding the longest -path in , , and can be resolved in linear time.

Theorem 3.

According to [19,20,21], an -path of maximum length can be calculated in linear time for a rectangular supergrid graph with , an L-shaped supergrid graph , or a C-shaped supergrid graph , given two distinct vertices s and t within the graph.

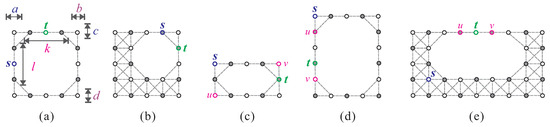

The focus of this paper is to examine the O-shaped supergrid graph denoted by , which has the structure illustrated in Figure 4c. Due to its symmetry, we limit our analysis to the following three cases, excluding the isomorphic ones:

- ;

- and ;

- .

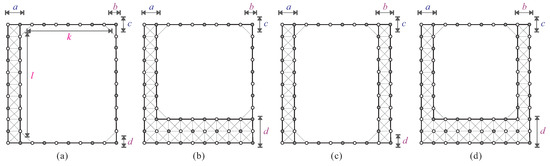

The above case that and can be further divided into four subcases: , and , and , and . These subcases are illustrated in Figure 9. Depending on the positions of s and t in , we can consider the following cases for the aforementioned three cases: ; and ; and .

Figure 9.

The subcases for and : (a) , (b) and , (c) and , and (d) .

We first verify the Hamiltonicity of O-shaped supergrid graphs with the following theorem.

Theorem 4.

For any O-shaped supergrid graph , there exists a Hamiltonian cycle contained within it.

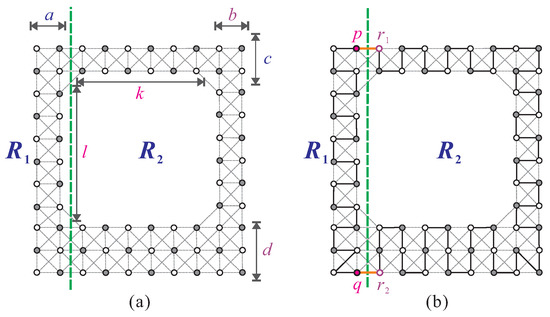

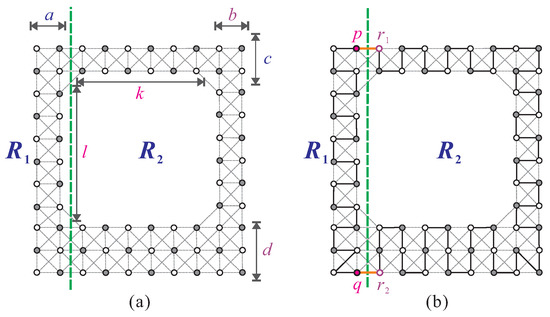

Proof.

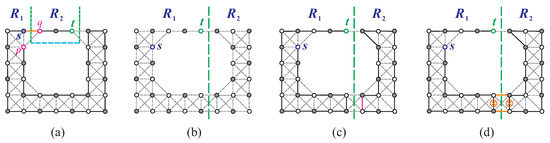

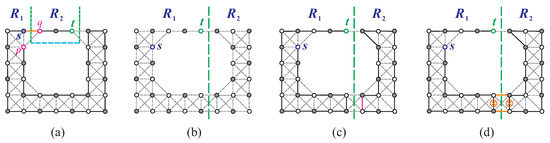

To obtain two disjoint supergrid subgraphs and from , we first make one vertical separation, as shown in Figure 10a. Let and be two vertices of , and let and be two vertices of , as depicted in Figure 10b. Note that and . Since does not satisfy condition (F1), contains a Hamiltonian -path according to Lemma 2. Similarly, contains a Hamiltonian -path according to Theorem 1, as it does not satisfy conditions (F1)–(F2) and (F4)–(F6). Then, forms a Hamiltonian -path of . Since , P is a Hamiltonian cycle of . The constructed Hamiltonian cycle is depicted in Figure 10b. □

Figure 10.

(a) One vertical separation on to obtain and , and (b) the constructed Hamiltonian cycle of , with solid bold lines indicating the cycle.

We can see from the above construction that if , then the constructed Hamiltonian cycle of satisfies being a flat face.

3. Forbidden Conditions for Hamiltonian Connectivity in O-Shaped Supergrid Graphs

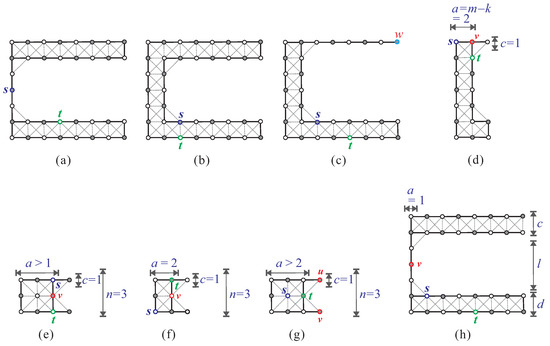

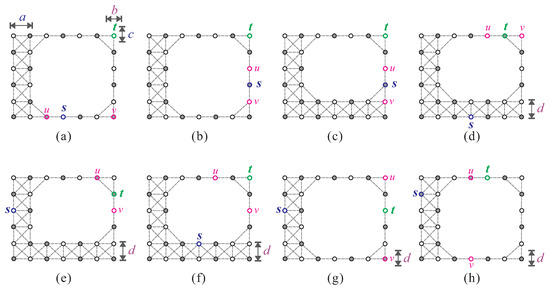

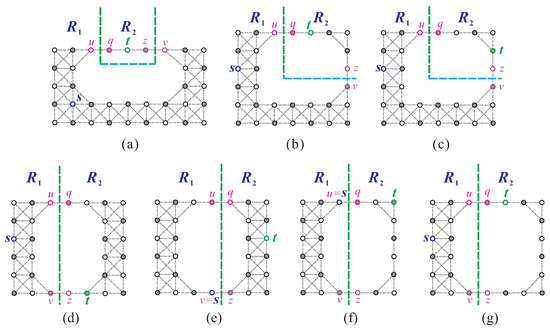

This section aims to identify all cases where O-shaped supergrid graphs do not contain a Hamiltonian -path. Although there are no cut vertices in these graphs, there are vertex cuts. Therefore, we have a forbidden condition, referred to as condition (F1), for the non-existence of (see Figure 11a,b).

Figure 11.

does not exist when (a,b) is a vertex cut; (c,d) ; and (e) , , and .

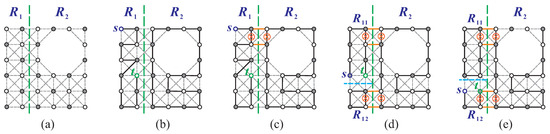

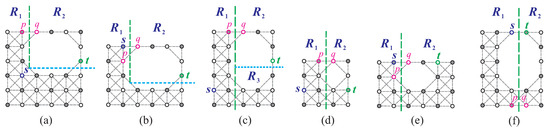

In the following, we explore the other forbidden conditions for the non-existence of a Hamiltonian -path in O-shaped supergrid graphs. We examine the sizes of parameters a, b, c, and d, and list the forbidden conditions as follows.

- (F10)

- When and , is not a vertex cut, and one of the following cases occurs:(1) , , and (see Figure 11c);(2) , , , and (see Figure 11d).

- (F11)

- When , , , and , is not a vertex cut, and (see Figure 11e).

- (F12)

- , , , and one of the following cases occurs:(1) and (see Figure 12a);

Figure 12. For O-shaped supergrid graphs with and , the forbidden conditions for the existence of a Hamiltonian -path are as follows: (a) when , , , and ; (b) when , , , and ; and (c,d) when , , , , and .(2) and (see Figure 12b).

Figure 12. For O-shaped supergrid graphs with and , the forbidden conditions for the existence of a Hamiltonian -path are as follows: (a) when , , , and ; (b) when , , , and ; and (c,d) when , , , , and .(2) and (see Figure 12b).

- (F13)

- , , , and one of the following cases occurs:(1) ; ; , or and ; and one of the following occurs:(1.1) , , and (see Figure 12c,d);(1.2) and (see Figure 13a);

Figure 13. O-shaped supergrid graphs with and , in which there is no Hamiltonian -path, where (a) case (1.2) of condition (F13) is satisfied, (b,c) case (1.3) of condition (F13) is satisfied, (d–f) case (2) of condition (F13) is satisfied, and (g,h) case (3) of condition (F13) is satisfied.(1.3) , , and (see Figure 13b,c);(2) ; ; ; , or and ; and one of the following occurs:(2.1) , , and (see Figure 13d);(2.2) , , and (see Figure 13e);(2.3) and (see Figure 13f);(3) ; ; ; and , or and (see Figure 13g,h).

Figure 13. O-shaped supergrid graphs with and , in which there is no Hamiltonian -path, where (a) case (1.2) of condition (F13) is satisfied, (b,c) case (1.3) of condition (F13) is satisfied, (d–f) case (2) of condition (F13) is satisfied, and (g,h) case (3) of condition (F13) is satisfied.(1.3) , , and (see Figure 13b,c);(2) ; ; ; , or and ; and one of the following occurs:(2.1) , , and (see Figure 13d);(2.2) , , and (see Figure 13e);(2.3) and (see Figure 13f);(3) ; ; ; and , or and (see Figure 13g,h).

The following lemma presents the necessary condition for the existence of a Hamiltonian -path in O-shaped supergrid graph .

Lemma 5.

If exists, then must not satisfy conditions and –.

Proof.

If satisfies any of conditions (F1) or (F10)–(F13), we can show that does not exist as follows: For condition (F1), the lemma clearly holds true, as shown in Figure 11a,b. For conditions (F10)–(F13), we can refer to Figure 11c–e, Figure 12, and Figure 13. Let v and u be two vertices depicted in these figures. It is clear that no Hamiltonian -path in can contain both vertices u and v. □

All possible cases for the forbidden conditions for the existence of a Hamiltonian -path in are considered in this section. In the next section, we prove that if does not satisfy conditions (F1) and (F10)–(F13), then contains a Hamiltonian -path.

4. The Hamiltonian Connectivity of -Shaped Supergrid Graphs

This section aims to demonstrate the existence of a Hamiltonian -path in when does not satisfy conditions (F1) and (F10)–(F13). The following three lemmas consider the following three cases individually: ; and ; and .

Lemma 6.

Let us assume that is an O-shaped supergrid and that s and t are two distinct vertices in the graph. If and does not satisfy conditions and , then it follows that has a Hamiltonian -path.

Proof.

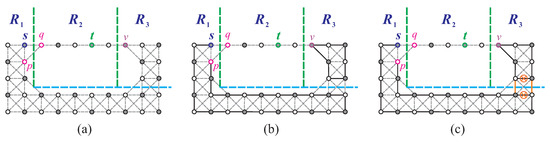

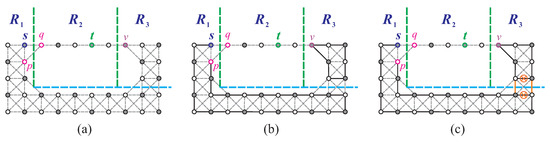

Due to symmetry, we only need to examine three cases: ; and ; and . The cases that are isomorphic, as shown in Section 2, are not considered. Then, there are the following three cases.

Case 1: . We first make a vertical separation on to obtain two disjoint supergrid subgraphs and , where (see Figure 14a). Then, we consider , or together with either , or and either or . Let the following hold: ; ; and either , or s or and . Then, satisfies condition (F1) or (F10). Without loss of generality, we assume that , and for the case , we assume that . We partition horizontally into two subgraphs and , where and , and if ; otherwise, (see Figure 14b,c). Let , , and such that , , , , , and if ; otherwise, . We consider . Since , , and , it is clear that does not satisfy conditions (F1)–(F2) and (F4)–(F6). We then consider and . If either of these subgraphs satisfies condition (F1), then satisfies condition (F10), which is a contradiction. Therefore, neither nor satisfies condition (F1). As , , and fail to satisfy conditions (F1)–(F2) and (F4)–(F6), Theorem 1 implies the existence of Hamiltonian paths , , and in , , and , respectively, with endpoints , , and (refer to Figure 14d). Concatenating these paths as results in a Hamiltonian -path in , as shown in Figure 14e.

Figure 14.

(a) A vertical separation on is performed with the constraints that , and ; (b,c) a horizontal separation is performed on , where (b) assumes that s and t are adjacent and (c) assumes that s and t are non-adjacent; (d) Hamiltonian paths are constructed for , , and ; and (e) a Hamiltonian -path is constructed in , with bold lines representing the constructed path.

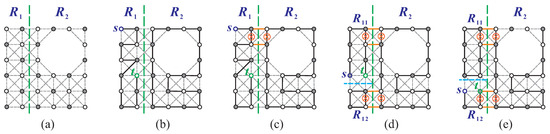

Case 2: and . We can divide this into two subcases based on the size of a:

Case 2.1: . For this subcase, we begin by conducting a vertical separation on . This results in two separate supergrid subgraphs, and , where (refer to Figure 15a). Depending on whether or not , we consider the following subcases.

Figure 15.

(a) A vertical separation on , where , , and , is performed to obtain and . (b–d,f) Vertical and horizontal separations on are performed. (e) A horizontal separation on is performed. Note that bold lines represent the constructed Hamiltonian path.

Case 2.1.1: s or . We can assume, without loss of generality, that . Then, or as the following two subcases.

Case 2.1.1.1: . In this subcase, we first perform both vertical and horizontal separations on , which results in two separated supergrid subgraphs, and , with and (refer to Figure 15b,c). We then choose , , and such that , , , , , and if ; otherwise, . We then consider and and show that they do not satisfy certain conditions necessary for the existence of a Hamiltonian -path of . Specifically, violates conditions (F1)–(F2) and (F4)–(F6), since , , and . On the other hand, violates conditions (F1), (F2), and (F3), due to the relationship between s and p. Despite these complications, we can construct a Hamiltonian -path of by following an approach similar to that in Case 1. Figure 15b,c depict the Hamiltonian -paths constructed in this subcase.

Case 2.1.1.2: . In the case of , we can construct a Hamiltonian -path of using symmetry, similarly to Case 2.1.1.1. Specifically, we set , , , , , and (refer to Figure 15d). In the case of , we perform vertical and horizontal separations on to obtain two disjoint supergrid subgraphs, and , where and (see Figure 15d). We then choose , , and such that , , , , , and if ; otherwise, . We can then construct a Hamiltonian -path of using an approach similar to that in Case 1. An example of the Hamiltonian -path constructed in this subcase is shown in Figure 15d.

Case 2.1.2: . Assuming without loss of generality, there are two cases to consider. First, let us consider . In this case, a Hamiltonian -path of can be constructed similarly to Case 1, where (see Figure 15e). Next, let us consider . Then, a Hamiltonian -path of can be constructed similarly to Case 2.1.1.1, where , , and (see Figure 15f). Figure 15e,f depict the Hamiltonian -paths of constructed in this subcase.

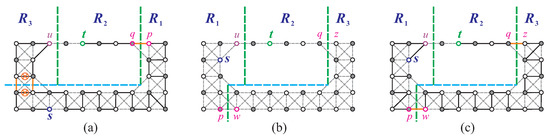

Case 2.2: . To obtain two separated supergrid subgraphs and , we perform a vertical separation on . The value of is determined as , as shown in Figure 16a. The resulting subcases depend on the locations of s and t and can be categorized as the following three subcases.

Figure 16.

(a) A vertical separation on , where and ; (b) a Hamiltonian -path in and a Hamiltonian cycle in ; (c) a Hamiltonian -path in , where is not a vertex cut of ; (d,e) horizontal separation on and Hamiltonian -paths of , where is a vertex cut of and where in (b–e), s and t are in , the constructed Hamiltonian -path is indicated by bold lines, and ⊗ denotes the destruction of an edge during the construction of the Hamiltonian path.

Case 2.2.1: . Based on the value of and the relationship between and , we can divide it into the following two subcases.

Case 2.2.1.1: Either , or and one of the following: , , or . In this subcase, is not a vertex cut of (refer to Figure 16b). We consider and check that it does not easily satisfy condition (F1). Therefore, according to Lemmas 3–4, there exists a Hamiltonian -path in in which one edge faces . Applying Theorem 4, contains a Hamiltonian cycle such that one flat face faces . Then, there exist two edges and such that (as shown in Figure 16b). According to Statement (2) of Proposition 1, and can be combined into a Hamiltonian -path of . The construction of such a Hamiltonian path is depicted in Figure 16c.

Case 2.2.1.2: and . In this subcase, is a vertex cut of . We then separate horizontally into two disjoint supergrid subgraphs and , where if , and if (see Figure 16d,e). If , then s and t belong to ; otherwise, they belong to . Without loss of generality, let us assume that s and t are both in . Since , does not satisfy condition (F1). By Lemmas 3 and 4, contains a Hamiltonian -path in which one edge is facing . By Lemma 1 and Theorem 4, and each contain a Hamiltonian cycle, and , respectively. Hence, there exist four edges, i.e., , , , and , such that and , as illustrated in Figure 16d. By Statements (1) and (2) of Proposition 1, , , and can be combined into a Hamiltonian -path of . The construction of such a Hamiltonian path is depicted in Figure 16d. For the case where s and t belong to , a Hamiltonian -path of can be constructed in the same way, as shown in Figure 16e.

Case 2.2.2: . Since and are both less than or equal to a, we know that (refer to Figure 16a and Figure 17a). Without loss of generality, let . We perform a vertical separation and a horizontal separation on to create three disjoint supergrid subgraphs , , and . Let . Then, (see Figure 17a). A Hamiltonian -path of can be constructed similarly to Case 2.1.1.1, where , , and (see Figure 17a–c).

Figure 17.

A Hamiltonian -path of , where and , for (a–c) ; and (d) and .

Case 2.2.3: and . A Hamiltonian -path of can be constructed similarly to Case 2.2.2. Refer to Figure 17d for the construction of the path.

Case 3: . To construct a Hamiltonian -path of when , we can use the same approach as in Case 2.1. Similarly, for , we can construct a Hamiltonian -path of using the same method as in Case 2.2. □

Lemma 7.

Let us assume that is an O-shaped supergrid and that s and t are two distinct vertices in the graph. If , , and does not satisfy conditions and –, then there exists a Hamiltonian -path in .

Proof.

Let us consider that . In this case, ; ; and either , or and . Let the following hold: ; ; and either and , or . Then, satisfies condition (F1) or (F10). So, or , and it can be considered equivalent to Case 1 in Lemma 6. Thus, we assume that for the following cases. Additionally, for the case where , we can assume without loss of generality that . We now consider the following cases.

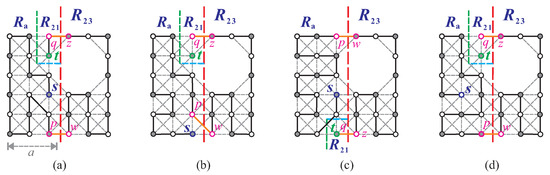

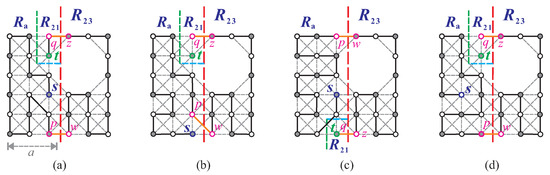

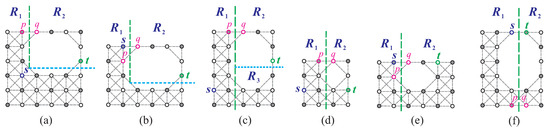

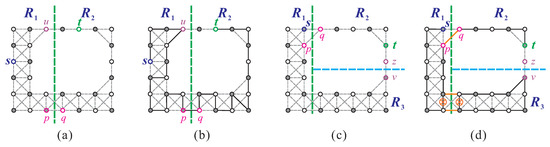

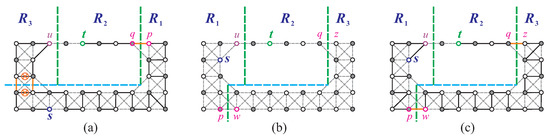

Case 1: . In this case, and . There are four subcases, each with different sizes of b, c, and d (refer to Figure 9). Depending on the placement of t, we examine the following subcases.

Case 1.1: and . In this subcase, either , or and . Let the following hold: or , , and ; or , , and . Then, satisfies (F11)–(F13). Note that the former ( or , , and ) satisfy condition (F12) or (F13), and the latter (, , and ) satisfy condition (F11). Next, we can consider the subsequent subcases.

Case 1.1.1: . First, we make a vertical separation on and obtain two separated supergrid subgraphs: and , where (refer to Figure 18a,b). We select and such that , , and if ; otherwise, . Next, we consider . As and , it is evident that does not satisfy conditions (F1), (F2), and (F4)–(F6). We also examine , where condition (F1) holds if and . However, this contradicts the fact that when . Therefore, does not satisfy condition (F1). Because and fail to satisfy conditions (F1), (F2), and (F4)–(F6), according to Theorem 1, there must exist a Hamiltonian -path and a Hamiltonian -path of and , respectively (as shown in Figure 18c). Finally, yields a Hamiltonian -path of , which is depicted in Figure 18d.

Figure 18.

(a,b) A vertical separation on for , , and ; (c) a Hamiltonian -path in and a Hamiltonian -path in for (a); (d) a Hamiltonian -path in for (a); and (e) a vertical separation on and a Hamiltonian -path in for , , and , where bold lines indicate the constructed Hamiltonian path.

Case 1.1.2: . In this subcase, . A Hamiltonian -path of can be constructed, following a method similar to that in Case 1.1.1, where we set and , and set (refer to Figure 18e). The resulting Hamiltonian -path of is also shown in Figure 18e.

Case 1.1.3: and . In this subcase, we have . Therefore, either , or . Then, we have the following two subcases.

Case 1.1.3.1: . In this subcase, we have that . We can construct a Hamiltonian -path for by making two vertical separations and one horizontal separation on resulting in two disjoint subgraphs and , as shown in Figure 19a. We then select vertices and such that , and if ; otherwise, . Next, we consider . Since , we only need to show that fails to satisfy condition (F1). If , then condition (F1) holds, but it contradicts when . We then consider . Since and , it is clear that does not satisfy condition (F1). Similarly to Case 1.1.1, we construct a Hamiltonian -path of . Figure 19a shows such a constructed Hamiltonian -path.

Figure 19.

(a) Two vertical separations and one horizontal separation on for , , and ; (b) a vertical separation on for , , and ; (c) a Hamiltonian -path in and a Hamiltonian cycle in for (b); and (d) a Hamiltonian -path in for (b), where bold lines represent the constructed Hamiltonian path and ⊗ indicates the destruction of an edge while constructing such a Hamiltonian -path.

Case 1.1.3.2: . In this subcase, we have . We then perform a vertical separation on to obtain two supergrid subgraphs and that are disjoint (refer to Figure 19b). We consider and note that since , , and , it does not satisfy conditions (F1), (F2), and (F4)–(F6). Thus, according to Theorem 1, has a Hamiltonian -path. We can construct a Hamiltonian -path of using the algorithm in [21], and we can ensure that one edge of faces . Using Theorem 2, contains a Hamiltonian cycle that can be constructed so that one flat face of faces (refer to Figure 19c). Thus, there are two edges and such that (see Figure 19c). Using Statement (2) of Proposition 1, and can be combined into a Hamiltonian -path of . Figure 19d shows the construction of such a Hamiltonian path.

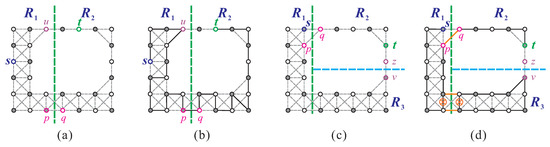

Case 1.2: and . In this subcase, one of the following applies: or , and ; or and . If either and , or and , then satisfies condition (F13). According to the position of t, we consider the following three subcases.

Case 1.2.1: . In this subcase, or . We can divide this subcase into the following two subcases.

Case 1.2.1.1: . We can construct a Hamiltonian -path of using an approach similar to that in Case 1.1.1. When , we consider , , and (see Figure 20a). When , we consider and (see Figure 20b). The Hamiltonian -paths of constructed using these cases are also depicted in Figure 20a,b.

Figure 20.

(a,b) A vertical separation on for , , , and ; (c,d) vertical and horizontal separations on for , , , , and ; (e) a Hamiltonian -path in and a Hamiltonian cycle in for (c); and (f) a Hamiltonian -path in for (c).

Case 1.2.1.2: and . To obtain three disjoint supergrid subgraphs , , and if (otherwise, ), where (see Figure 20c,d), we perform vertical and horizontal separations on . Then, we select and , such that , and if ; otherwise, . We consider first. If and , then condition (F1) is satisfied, which is a contradiction, since when . Next, we consider . Since , , and , it is easy to check that does not satisfy conditions (F1), (F2), and (F3). Therefore, using Theorem 1, there exists a Hamiltonian -path of and a Hamiltonian -path of . We note that is a canonical Hamiltonian path of . Then, we obtain a Hamiltonian -path of by combining and , which is depicted in Figure 20e. Using Lemma 1, contains a canonical Hamiltonian cycle . We can place one flat face of to face . Then, we can find two edges and such that (see Figure 20f). Using Statement (2) of Proposition 1, we can combine P and into a Hamiltonian -path of . The construction of such a Hamiltonian path is shown in Figure 20f.

Case 1.2.2: . To construct a Hamiltonian -path of , we follow an approach similar to that in Case 1.1.3.1, where two disjoint supergrid subgraphs and are as shown in Figure 21a,b.

Figure 21.

(a–c) Vertical and horizontal separations on for , , and or ; (d,e) a vertical separation on for and ; and (f) a vertical separation on for , , , and .

Case 1.2.3: . In this subcase, . A Hamiltonian -path of can be constructed similarly to Case 1.2.1.2. Here, let (as shown in Figure 21c).

Case 1.3: and one of the following: , and either , or and ; or and . A Hamiltonian -path of can be constructed in a way similar to that in Case 1.1.1. We set q to be , and if , then ; otherwise, (refer to Figure 21d,e). Note that ; ; and either , or and . Therefore, it is easy to verify that does not satisfy conditions (F1), (F2), and (F4)–(F6).

Case 2: . A Hamiltonian -path of can be constructed, similarly to Case 1.1.1, depicted in Figure 18c,d, where and where p and q are chosen as follows:

Let us consider . As and d are greater than or equal to 2, and and , it is obvious that does not satisfy conditions (F1), (F2), and (F4)–(F6). Now, let us consider . Condition (F1) holds only if or . However, this contradicts when or when . Therefore, does not satisfy condition (F1).

We have considered any case for constructing a Hamiltonian -path of , where and . Thus, this lemma holds true. □

Lemma 8.

Let us assume that is an O-shaped supergrid and that s and t are two distinct vertices in the graph. If and does not satisfy conditions and –, then there exists a Hamiltonian -path in .

Proof.

Using symmetry, we can only consider the cases of and , and and (please refer to the discussion after Theorem 3). The cases of and are isomorphic to Lemmas 6 and 7. Thus, we assume that and in the following. If and , then it must be the case that or . If and , then is a vertex cut of , which satisfies condition (F1). Therefore, without loss of generality, let us assume that when and . We now consider the following three cases.

Case 1: One of the following cases holds:

(1) , and or and ;

(2) , and or .

In these cases, let us assume that the vertex in the upper-right corner has coordinates if , or in the down-right corner if in . Using the same arguments as in the proofs of Lemmas 6 and 7, we can construct a Hamiltonian -path of in these cases. It is worth noting that these cases are equivalent to the assumptions made in Lemmas 6 and 7.

Case 2: and . If , then satisfies condition (F1). Thus, . A Hamiltonian -path of can be constructed similarly to Case 1.1.1 of Lemma 7, where , , and (see Figure 21f).

Case 3: ; , or and ; and , or and . A Hamiltonian -path of can be constructed in this case, assuming that the vertex in the upper-right corner has coordinates . The construction is similar to that in Case 1 of Lemma 6, when , and Lemma 7, when and . □

The Hamiltonian connectivity of O-shaped supergrid graphs is verified with the following theorem, which is based on Lemma 5 and Lemmas 6–8.

Theorem 5.

A Hamiltonian -path exists in the O-shaped supergrid graph with distinct vertices s and t, if and only if conditions and – are not satisfied by .

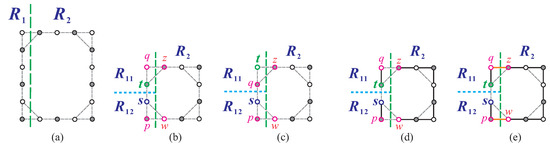

5. The Longest (s, t)-Path Algorithm

In Theorem 5, we know that if satisfies one of the conditions ((F1) and (F10)–(F13)), then contains no Hamiltonian -path. So, in this section, for these cases, we first establish upper bounds on the lengths of the longest paths between s and t. We then demonstrate that these upper bounds are equivalent to the lengths of the longest -paths in . It is worth noting that isomorphic cases are excluded, and we assume that . The cases that we consider are limited to , , and ; and (see Section 2). In this context, we use to denote the lengths of the longest paths between s and t, and to represent the upper bound on the length of the longest paths between s and t, where G is a rectangular, L-shaped, C-shaped, or O-shaped supergrid graph. Note that the length of a path is defined as the number of vertices on the path. The following lemmas present these upper bounds.

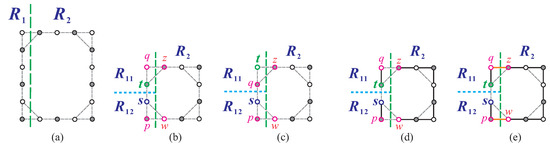

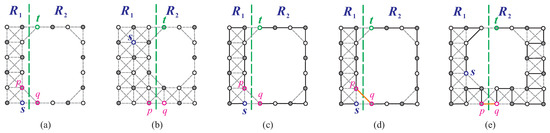

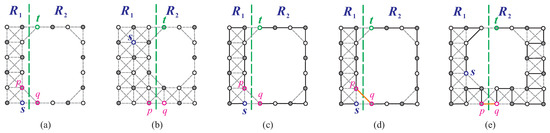

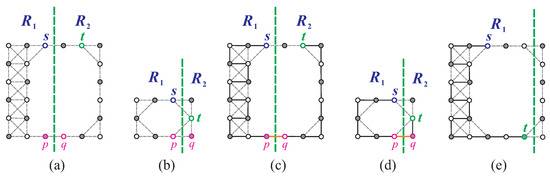

Our initial focus is on the scenario where forms a vertex cut of . In this case, we determine the upper bound of the length of the longest -path using the following lemma.

Lemma 9.

Let us assume that and that is a vertex cut of . The following conditions are satisfied:

- If and , then the length of any path between s and t cannot exceed (refer to Figure 22a).

Figure 22. The upper bound of the length of the longest -path, where is a vertex cut, when (a) (O1) holds, (b) (O2) holds, and (c,d) (O3) holds. Note that a vertical separation in is denoted by a bold dashed line.

Figure 22. The upper bound of the length of the longest -path, where is a vertex cut, when (a) (O1) holds, (b) (O2) holds, and (c,d) (O3) holds. Note that a vertical separation in is denoted by a bold dashed line. - If , , , and , then the length of any path between s and t cannot exceed (refer to Figure 22b).

- If , , , and , then the length of any path between s and t cannot exceed , where , , and (refer to Figure 22c,d).

Proof.

Let us consider Figure 22a–d. When we remove s and t from , we obtain two separated components, and . Therefore, any simple path between s and t can only pass through one of these components, implying that its length cannot exceed the size of the largest component. For condition (O1) (resp., condition (O2)), the length of any path between s and t is equal to (resp., ). Since (resp., ), it is apparent that the length of any path between s and t cannot exceed (resp., ). □

The next lemma provides an upper bound for the length of the longest -path in , when is not a vertex cut and , under the assumption that the graph satisfies conditions (F11)–(F13).

Lemma 10.

Let satisfy condition , , or (cases , , , and of ). Then, the following implications hold true:

- If satisfies condition , then the length of any -path cannot exceed , where , , , and (refer to Figure 23a).

Figure 23. The upper bound of the length of the longest -path in for (a) condition (F11); (b) case (2.1) of condition (F13); (c) cases (2.2) and (2.3) of condition (F13); (d,e) condition (F11); and (f,g) cases (1.1), (1.2), and (3) of condition (F13), where the bold dash line indicates vertical or horizontal separation on .

Figure 23. The upper bound of the length of the longest -path in for (a) condition (F11); (b) case (2.1) of condition (F13); (c) cases (2.2) and (2.3) of condition (F13); (d,e) condition (F11); and (f,g) cases (1.1), (1.2), and (3) of condition (F13), where the bold dash line indicates vertical or horizontal separation on . - If satisfies case (2.1) of condition , then the length of any -path cannot exceed , where , , , and (refer to Figure 23b).

- If satisfies case (2.2) or (2.3) of condition , then the length of any -path cannot exceed , where , , , and (refer to Figure 23c).

Proof.

Let us examine Figure 23. It is evident that for the longest -path P in , starting from s, P must traverse all or some vertices of , exit via u or v, enter via q or z, and terminate at t. Therefore, the length of any path between s and t cannot exceed . □

We finally consider the remaining conditions for the case where is not a vertex cut of . Specifically, we consider condition (F10) and case (1.3) of condition (F13).

Lemma 11.

Let and . If satisfies the following condition , then the length of any -path cannot exceed (see Figure 24a–c), where and if ; otherwise, , , , , , and .

Figure 24.

The upper bound of the length of the longest -path in for condition (O4), where (a,b) , , and ; and (c) , , and .

Condition is defined below.

- (O4)

- One of the following cases holds:

- (1)

- , , and (case (1) of condition (F10));

- (2)

- , , and (case (2) of condition (F10) and case (1.3) of condition (F13)).

Proof.

The proof follows an approach similar to that of Lemma 10 and can be visualized in Figure 24a–c. □

Let us define condition (O0) as follows:

- None of the conditions (F1), (F10), (F11), (F12), or (F13) are satisfied by .

Checking whether any satisfies one of conditions (O0), (O1), (O2), (O3), (O4), (F11), (F12), and (F13) is a straightforward task. If satisfies (O0), then . Otherwise, can be calculated using Lemmas 9–11. These calculations are summarized below, where :

Next, we demonstrate how to find the longest -path for O-shaped supergrid graphs. It should be noted that if satisfies condition (O0), then according to Theorem 5, it contains a Hamiltonian -path.

Lemma 12.

When satisfies any of conditions – and –, it follows that .

Proof.

To prove this lemma, we construct an -path P with length equal to . We consider the following cases.

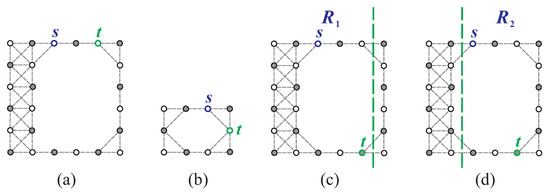

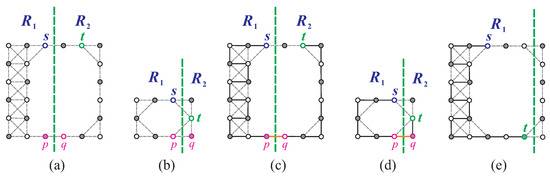

Case 1: Conditions (O1) and (O2) hold. Using Lemma 9, we obtain and for conditions (O1) and (O2), respectively. We consider Figure 22a,b and make a vertical separation on to create two disjoint supergrid subgraphs , and either if or if , where (see Figure 25a,b). We select a vertex and a vertex such that , , and . We then construct the longest -path in and the longest -path in using the algorithms from [19,21]. Finally, we create an -path , which forms the longest -path of . Figure 25c,d demonstrate the construction of such longest -path. The length of the constructed longest -path equals or .

Figure 25.

(a,b) Vertical separation on for conditions (O1) and (O2) respectively; (c,d) the longest -path in for (a,b), respectively; and (e) the longest -path in for (O3), where bold lines indicate the constructed longest -path.

Case 2: Condition (O3) holds. Using Lemma 9, we can express as , where and are two disjoint subgraphs of (refer to Figure 22c,d). Since and are both C-shaped supergrid graphs, we can apply the algorithm from [21] to construct the longest path between s and t in either or . The construction of such a path is shown in Figure 25e. The length of the constructed path is equal to or , which in turn is equal to by Lemma 9.

Case 3: Condition (F11) holds. Let us examine Figure 23a. According to Lemma 10, if satisfies condition (F11), then , where . There are two subcases to consider.

Case 3.1: . We begin by making two vertical separations and one horizontal separation on to obtain three disjoint supergrid subgraphs, , , and , as shown in Figure 26a. Let and , such that , , and if ; otherwise, . We consider and note that it does not satisfy conditions (F1)–(F3). Using the algorithms from [19,20], we can construct a Hamiltonian -path in and the longest -path in . We can construct such that its one edge is placed to face using the algorithm from [20]. Then, forms the longest -path of , as depicted in Figure 26b. According to Theorem 2, contains a Hamiltonian cycle . Using the algorithm in [20], we can construct such that its one flat face faces . Then, there exist two edges, and , such that (see Figure 26c). Using Statement (2) of Proposition 1, we can combine and into the longest -path P of . The construction of such longest path is depicted in Figure 26c. The length of the constructed longest -path is equal to .

Figure 26.

(a) Two vertical separations and one horizontal separation on for (F11), where ; (b) the longest -path in and a Hamiltonian cycle of ; and (c) the longest -path in for (a), where bold lines indicate the constructed longest -path and ⊗ represents the destruction of an edge while constructing such an -path.

Case 3.2: . Let us examine the following scenarios.

Case 3.2.1: . Let be the coordinates of the vertex in the upper-right corner of . Then, we can construct the longest -path of in a way similar to that in Case 3.1 (as shown in Figure 27a).

Figure 27.

(a) The longest -path in for condition (F11), where and ; (b) three vertical separations and one horizontal separation on for (F11), where and ; and (c) the longest -path in for (b).

Case 3.2.2: . We begin by partitioning into three non-overlapping subgraphs, , , and , using three vertical separations and one horizontal separation (refer to Figure 27b). Let , , and such that , , , , , and if ; otherwise, . We observe that and do not satisfy conditions (F1)–(F3). To construct a Hamiltonian -path and a Hamiltonian -path of and , respectively, we use the algorithm proposed in [20]. Using the algorithm proposed in [19], we construct the longest -path in . Finally, we concatenate , , and to obtain the longest -path P of , i.e., . The size of the constructed longest -path is . We illustrate the construction of such longest -path of in Figure 27c.

Case 4: Case 2 of Condition (F13) holds. Let us consider Figure 23b,c. Based on Lemma 10, we have , where ℓ is the maximum of two values: and (or and , depending on the subcase). We consider the following two subcases.

Case 4.1: (resp., . The longest -path of can be obtained in a way similar to that in Case 1, by making two vertical separations on to obtain two disjoint supergrid subgraphs and , where , and (see Figure 28a). Using Lemma 10, the size of the constructed longest -path is (resp., ). The construction of such longest -path of is depicted in Figure 28b.

Figure 28.

(a) A vertical separation on for case (2) of condition (F13), where ; (b) the longest -path in for (a); (c) a vertical separation and horizontal separations on for case (2) of condition (F13), where ; and (d) the longest -path in for (c).

Case 4.2: (resp., . The longest -path of can be constructed in a way similar to that in Case 3.1. Let , , , , , and if ; otherwise, (see Figure 28c). The size of the constructed longest -path is equal to (resp., . The construction of such longest -path of is illustrated in Figure 28d.

Case 5: Condition (F13) (cases 1.1 and 3), (F12), or (O4) holds. Using Lemma 10 or 11, we can express as . To construct the longest -path of , we consider Figure 23d–g and Figure 24. Since and are C-shaped supergrid graphs, we can use the algorithm proposed in [21] to construct the longest -path , the longest -path in , the longest -path , and the longest -path in . Then, we can form the longest -path of by concatenating and , or and . □

Finally, we conclude with the following theorem.

Theorem 6.

Let be an O-shaped supergrid graph with vertices s and t. Then, there exists a linear-time algorithm for finding the longest -path of .

Proof.

The algorithm presented in Algorithm 1 solves the problem in linear time by combining the results of Lemmas 9–12 and Theorem 5. Therefore, the theorem follows. □

| Algorithm 1: The longest -path algorithm |

Input: An O-shaped supergrid graph and two distinct vertices s and t in it. Output: The longest -path.

|

6. Conclusions

We provide the necessary conditions for the existence of a Hamiltonian path in O-shaped supergrid graphs between any two given vertices. Moreover, we show that these necessary conditions are sufficient, by presenting a linear-time algorithm for computing the Hamiltonian path between any two vertices, except for five forbidden conditions. Hence, O-shaped supergrid graphs are Hamiltonian-connected, except in the case of the five forbidden conditions. Furthermore, we present a linear-time algorithm for computing the longest -path of an O-shaped supergrid graph for any two given vertices s and t, provided that the forbidden conditions are satisfied. These algorithms can be regarded as the first attempts to solve the Hamiltonian and longest -path problems for supergrid graphs with holes, where O-shaped supergrid graphs form a special class of supergrid graphs with holes. Although the Hamiltonian and longest -path problems are NP-complete for general supergrid graphs, their complexities are still unknown for supergrid graphs with or without holes. We leave them as open problems for interested readers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.K.-K. and R.-W.H.; methodology, F.K.-K. and R.-W.H.; validation, F.K.-K. and R.-W.H.; formal analysis, R.-W.H.; writing—original draft, R.-W.H.; writing—review and editing, F.K.-K. and R.-W.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan, under grant number MOST 110-2221-E-324-007-MY3.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous referees for many useful comments and suggestions, which have improved the presentation and correctness of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Garey, M.R.; Johnson, D.S. Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness; Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.S. The NP-complete column: An ongoing guide. J. Algorithms 1985, 6, 434–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertossi, A.A.; Bonuccelli, M.A. Hamiltonian circuits in interval graph generalizations. Inform. Process. Lett. 1986, 23, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damaschke, P. The Hamiltonian circuit problem for circle graphs is NP-complete. Inform. Process. Lett. 1989, 32, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golumbic, M.C. Algorithmic Graph Theory and Perfect Graphs, 2nd ed.; Annals of Discrete Mathematics 57; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, V.S.; Orlovich, Y.L.; Werner, F. Hamiltonian properties of triangular grid graphs. Discrete Math. 2008, 308, 6166–6188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, R.W.; Yao, C.C.; Chan, S.J. The Hamiltonian properties of supergrid graphs. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2015, 602, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, M.S. An NP-hard problem in bipartite graphs. SIGACT News 1976, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itai, A.; Papadimitriou, C.H.; Szwarcfiter, J.L. Hamiltonian paths in grid graphs. SIAM J. Comput. 1982, 11, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondy, J.A.; Murty, U.S.R. Graph Theory with Applications; Macmillan: London, UK; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, R.W.; Keshavarz-Kohjerdi, F.; Tseng, Y.M.; Qiu, G.H. Finding longest (s, t)-paths of O-shaped supergrid graphs in linear time. In Proceedings of the 10th IEEE International Conference on Awareness Science and Technology 2019 (iCAST’2019), Morioka, Japan, 23–25 October 2019; pp. 252–259. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, R.W.; Keshavarz-Kohjerdi, F. The longest (s, t)-paths of O-shaped supergrid graphs. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.08558. [Google Scholar]

- Zamfirescu, C.; Zamfirescu, T. Hamiltonian properties of grid graphs. SIAM J. Discret. Math. 1992, 5, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.D.; Shen, H.; Topor, R. An efficient algorithm for constructing Hamiltonian paths in meshes. Parallel Comput. 2002, 28, 1293–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenhart, W.; Umans, C. Hamiltonian cycles in solid grid graphs. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (FOCS’97), Miami Beach, FL, USA, 20–22 October 1997; pp. 496–505. [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz-Kohjerdi, F.; Bagheri, A. Hamiltonian paths in L-shaped grid graphs. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2016, 621, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishat, R.I.; Srinivasan, V.; Whitesides, S. 1-complex s, t Hamiltonian paths: Structure and reconfiguration in rectangular grids. J. Graph Algorithms Appl. 2023, 27, 281–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, R.W. Hamiltonian cycles in linear-convex supergrid graphs. Discret. Appl. Math. 2016, 211, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, R.W.; Li, C.F.; Chen, J.S.; Su, Q.S. The Hamiltonian connectivity of rectangular supergrid graphs. Discret. Optim. 2017, 26, 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz-Kohjerdi, F.; Hung, R.W. The Hamiltonicity, Hamiltonian connectivity, and longest (s, t)-path of L-shaped supergrid graphs. IAENG Int. J. Comput. Sci. 2020, 47, 378–391. [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz-Kohjerdi, F.; Hung, R.W. Finding Hamiltonian and longest (s, t)-paths of C-shaped supergrid graphs in linear time. Algorithms 2022, 15, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).