Abstract

The authenticated key exchange (AKE) protocol can ensure secure communication between a client and a server in the electricity transaction of the Energy Internet of things (EIoT). Park proposed a two-factor authentication protocol 2PAKEP, whose computational burden of authentication is evenly shared by both sides. However, the computing capability of the client device is weaker than that of the server. Therefore, based on 2PAKEP, we propose an authentication protocol that transfers computational tasks from the client to the server. The client has fewer computing tasks in this protocol than the server, and the overall latency will be greatly reduced. Furthermore, the security of the proposed protocol is analyzed by using the ROR model and GNY logic. We verify the low-latency advantage of the proposed protocol through various comparative experiments and use it for EIoT electricity transaction systems in a Metaverse scenario.

MSC:

68M12

1. Introduction

Authentication schemes in the traditional Energy Internet of Things (EIoT) are generally implemented with the help of Public Key Infrastructure (PKI). To simplify the management of public-key certificates, Shamir [1] introduced the identity-based cryptography scheme (IBC). This scheme directly uses the identity to generate the public key, without certificates or public key directories.

ID-based single-factor authentication scheme is not secure [2]. Attackers can compromise this scheme by dictionary attacks [3], rainbow tables [4], or social engineering techniques [5].

Thus, researchers have proposed two-factor authentication (2FA) [6,7], which combines representative data (ID/password) with personal possession factors (i.e., smart cards or mobile phones) to provide stronger security protection.

When ID-based 2FA authentication scheme is applied in EIoT, latency becomes an issue that has not been well studied [8,9]. Especially when electricity transactions based on EIoT are realized in Metaverse in the near future, high latency will affect the validity of data information (i.e., payment information data) [10]. Therefore, compared with the traditional payment systems, the EIoT payment systems in the Metaverse should meet higher requirements regarding the latency [11].

At present, the Metaverse devices are typically virtual helmets and smart glasses. A two-factor authentication protocol using smart cards (security chips that are embeded in these devices) can enhance the security of the protocol. In related work, we found that 2PAKEP is more secure than previous protocols [12,13,14,15,16]. In order to satisfy the requirement of low latency in EIoT (or future EIoT in Metaverse), we propose a low-latency ID-based two-factor authentication protocol LLAKEP. Our main contributions are summarized below.

- A low-latency ID-based two-factor authentication protocol LLAKEP has been proposed. In the case of unbalanced computing capability between the two parties of the protocol, LLAKEP reduces the computational burden on one side. Compared with 2PAKEP [17], experimental results show that LLAKEP requires less computation time and less running time;

- The security of LLAKEP is analyzed by using the ROR (Real-or-Random) model and GNY (Gong–Needham–Yahalom) logic. Analysis results show that LLAKEP achieves the security goals of an AKE protocol;

- A use case has been implemented. We applied LLAKEP to EIoT electricity transaction systems in a Metaverse scenario. Results show that LLAKEP will effectively reduce latency.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the related work. Section 3 introduces the soultion methodology. Section 4 introduces the preliminaries. Section 5 proposes the LLAKEP. In Section 6, the security of the LLAKEP is analyzed. The experiment results of LLAKEP are shown in Section 7. Finally, a conclusion is summarized in Section 8.

2. Related Work

Das [12] designed an ID-based authentication protocol (the D protocol) using bilinear pairings. However, the D protocol is subject to forgery attacks [18]. Many improved protocols have been proposed based on D protocol [13,14,15,16,17]. Table 1 lists the characteristics, limitations, and disadvantages of different protocols.

Table 1.

Comparison of the characteristics, limitations, and disadvantages of different protocols.

Because of the inefficiency of bilinear pairing cryptography, researchers have proposed many ID-based authentication protocols using scalar multiplication. Yang and Chang [13] proposed an authentication protocol based on ID (the YC protocol) in 2009. However, Yoon and Yoo [14] found that the YC protocol [13] is prone to simulated attacks. In addition, the YC protocol cannot provide perfect forward security. Therefore, an improved ID-based protocol (the YY protocol) is proposed by Yoon and Yoo. The YY protocol can eliminate the defects of the YC protocol [13]. However, the YY protocol cannot provide perfect forward security. In 2012, He [15] proposed a protocol (the HDB protocol). The HDB protocol can guarantee perfect forward security. However, in 2013, Chou [19] showed that the HDB protocol [15] has defects concerning the private key verification process, and legitimate users cannot confirm whether the private key of the other party is correct. Thus, two improved security protocols (the C1 protocol, and the C2 protocol) were proposed. In 2015, Yang [20] proved that the HDB protocol [15] cannot resist simulation attacks and unknown key sharing attacks, and then Yang proposed an improved ID-based authentication key exchange protocol (the Y protocol).

However, there are some defects in the above-mentioned ID-based authenticated protocols. Their protocols have issues concerning clock synchronization and user anonymity [16]. To solve the issues, Qi and Chen [16] proposed an ID-based two-factor mutual authentication protocol with smart cards (the QC protocol). Qi and Chen claim the QC protocol is resistant to many attacks. However, in 2018, Park [17] proved that the QC protocol is not resistant to simulated user attacks, password change attacks, insider attacks, and offline password guessing attacks. Thus, Park [17] proposed an improved protocol 2PAKEP and proved that it could solve these security issues. LLAKEP uses an improved algorithm to reduce the latency of 2PAKEP. In addition, LLAKEP uses a security chip.

At present, smart cards are widely used in medical, educational, and other scenarios [21,22,23]. Using smart cards as an authentication factor can improve the security of system authentication. The most widely used smart cards in payment systems are mainly microprocessor chips. In addition, the Trustzone [24,25] is included in the microprocessor chip, which provides security features for smart wearable devices [26].

3. Solution Methodology

3.1. Research Methods

We research the low latency algorithms based on 2PAKEP. Meanwhile, we use security analysis and performance analysis to verify the advantages of LLAKEP.

3.2. Security Analysis Methods

First, we prove the security of LLAKEP in the ROR model. Second, we use GNY logic to prove the security of LLAKEP. Finally, we verify the security of the protocol using Prolog.

3.3. Performance Analysis Methods

We use a Raspberry Pi and a laptop to simulate two communication parties. The protocol is implemented in Python. The running time and computation time of LLAKEP and other protocols are compared by experiments.

4. Preliminaries

The system model, ROR model, and computational assumptions are introduced in this section.

4.1. System Model

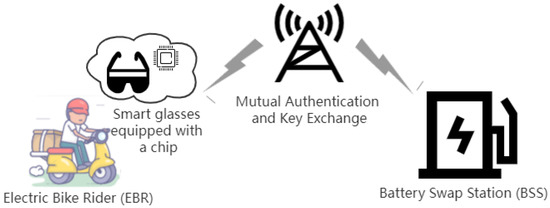

In the EIoT, LLAKEP can be used to secure the key agreement for the communication of electricity transactions. A specific example is shown in Figure 1, where the electric bike rider is ready to swap his battery, and their device (smart glasses) and the battery swap station will establish a secure link through LLAKEP. The communication of transaction information, such as battery types and payment information, can then be encrypted through the session key. One thing to note is that the smart glasses in the example are the user’s Metaverse interface, which implies that a "gap" in computing capabilities exists between the two ends of these common communication devices. More specifically, the smart glasses with a microprocessor have weaker computing capabilities than the battery swap station.

Figure 1.

A typical architecture of EIoT.

Before the electric bike rider uses the smart glasses to enter the Metaverse for electricity transactions, some user information needs to be stored in the memory of the smart glasses in the initial stage. Assuming that the electric bike rider has obtained a registered microprocessor chip, and has a password, and the microprocessor chip is equipped in the user’s smart glass, then, as an initiator, the smart glasses authenticate with an energy device.

4.2. ROR Model

Abdalla, Fouque, and Pointcheval initially proposed the ROR model for password-based key exchange [27]. One of its significant features is that the attacker no longer has a Reveal query compared with the BPR model [28], but instead performs a simulation of a compromise caused by the misuse of a session key via the uniform Test query. This Test query can be called multiple times. Furthermore, the ROR model has been proved to be stronger than the BPR security model [27].

We introduce the primary components associated with the ROR model below.

Participants and instances. Let oracles and be the instances t and s of participants and running protocol , respectively.

Instance state. will be in the accepted state if it has received the final message according the protocol . The session identification of is the cocatenation of exchanged messages in the session.

Partnering. We say that and are the partners if the following two conditions are satisfied: (1) both and are in the accepted state, (2) and have the same and mutually authenticated each other.

Freshness. If the session key of and is not compromised by a reveal query or query defined below, we say and are fresh.

Adversary. An active adversary may intercept, delete, modify, or inject the messages over public channels by the given queries:

- This query models the eavesdropping attack that permits to learn the messages exchanged between and .

- This query models the active attack that permits to transmit a message to a participant’s instance .

- This query models another active attack that permits to extract all the sensitive secret parameters stored in a mobile device () or microprocessor chip ().

- Before the game starts, an unbiased coin b is flipped. If is fresh, this query returns the real session key if , or a random key in the key space of if ; otherwise, if is not fresh, this query returns the invalid symbol ⊥.

We restrict to access a limited number of queries in a formal security analysis. At the same time, is permitted to access an infinite number of queries.

Semantic security. Let ’s guesse be , and be the winning probability in the game. A polynomial t time adversary ’s advantage in breaking the semantic security of session key is denoted by

Random oracle. We model the public one-way cryptographic hash function as a random oracle ().

4.3. Computational Assumption

We use elliptic curve cryptography because it is one of the best candidates among the existing public key cryptographic techniques. Two relevant hardness assumptions are described below.

Definition 1

(Elliptic curve discrete logarithm problem (ECDLP)). Given an elliptic curve E over finit field , and , find the discrete logarithm d, such that .

Definition 2

(Elliptic curve decisional Diffie–Hellman problem (ECDDHP)). Given an elliptic curve E over finite field , a generator P of E, and three random elements , and , distinguish the triples and .

The ECDLP and ECDDHP are computationally hard problems when p is large.

5. The Low-Latency Protocol

In this section, we mainly introduce the process of LLAKEP. The symbols used in LLAKEP are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Symbols used in LLAKEP.

5.1. Initialization Phase

This phase is performed in the battery swap station . The specific process is described as follows.

BSS-1: selects an elliptic curve whose base point is P. Meanwhile, the order of p is set to n.

BSS-2: generates a private key from , and calculates the public key by .

BSS-3: chooses two hash functions (collision-resistant) and . At the end, publishes the system parameters .

5.2. User Registration Phase

Electric bike rider needs to register with battery swap station before swapping batteries. The registration takes place in a secure channel, and the specific process (Table 3) is described as follows.

Table 3.

User registration phase.

EBR-1: inputs the and on the smart glasses. After the input is completed, the microprocessor chip generates two random numbers and calculates and . Finally, submits:

to the by using a secure channel.

BSS-2: checks whether and are valid after receiving . If they already exist in the database, returns a message to asking for a new .

BSS-3: calculates . After that, stores and sends to by using a secure channel.

EBR-4: After receiving , calculates and stores , v, and C in the microprocessor chip.

5.3. Authentication and Key Exchange (AKE) Phase

After registration, when electric bike rider wants to swap batteries, he needs to send some information for identity authentication. The key algorithms of this phase are shown in Algorithms 1 and 2. denotes scalar multiplication on an elliptic curve, and its computation is time-consuming. represents addition on an elliptic curves, and represents negation operations on an elliptic curves. These two cryptographic operations take less time. represents the key derivation function. We transferred a scalar multiplication on the side in the original protocol algorithm to the side. The specific process (Table 4) of the AKE phase is described as follows.

| Algorithm 1 calculates |

|

Table 4.

Mutual authentication and key exchange phase.

| Algorithm 2 calculates |

|

EBR-1: inputs and using a smart glasses. Then calculates , and . After that, checks whether is equal to C. After successful verification, generates a random number and a current timestamp , and computes , , and . Then, sends:

to the by using a public channel.

BSS-2: verifies whether the difference between and the reception time is less than the maximum transmission latency after receiving . If it is greater than , the protocol will stop running. Otherwise, calculates . After that, computes and , and checks whether is equal to . After successful verification, generates a random number and a current timestamp . Then computes , and . At the end, sends:

to by using a public channel.

EBR-3: After receiving , first verifies whether the difference between and the reception time is less than . If it is greater than , the protocol will stop running. Otherwise, calculates , , and checks whether is equal to . After successful verification, generates the current timestamp , and computes the session key . At the end, calculates , and sends:

to the through a public channel.

BSS-4: After receiving , verifies whether the difference between and the reception time is less than . If it is greater than , the protocol will stop running. Otherwises computes the session key , and checks whether is equal to . If they are equal, the mutual authentication and session key agreement phase have successfully be completed. Finally, the same session key will be store, and it will be used for secure commucations of and .

5.4. Password Change

Electric bike riders can change their password at any time. The specific process (Table 5) is described as follows.

Table 5.

Password change activity.

EBR-1: first inputs and old password through a microprocessor chip.

MC-2: computes , . After that, calculates , and then verifies C is equal to or not. If it is satisfied, asks to input a new password.

MC-3: After receiving the new password, calculate , , , and . Finally, store , and in the microprocessor chip and delete old parameters.

5.5. Comparison of LLAKEP and Other Protocols

From the experimental results of He et al.’s scheme [15], it can be obtained that the most time spent is on the elliptic curve scalar multiplication operation, followed by the execution of a map-to-point hash function and a modular inversion operation, while the time spent on the execution of a hash operation, a dissimilarity operation, a message authentication code operation, and a key derivation function is very short. The main cryptographic operations involved in the authentication phase of the relevant protocols and LLAKEP are shown in Table 6. denotes the device with limited computing power, and denotes the device with strong computing power.

Table 6.

Comparison of computation costs.

We can see that the total number of elliptic curve scalar multiplication required by LLAKEP is fewer than that of the protocols proposed in [13,14], so the total computing time of LLAKEP is less than theirs. Compared to the protocols proposed in [15,16,17], of LLAKEP needs to perform fewer elliptic curve scalar multiplications, which leads to the computing time being cut, thus reducing the overall latency.

6. Security Analysis

This section proves the security of LLAKEP in the ROR model.

6.1. Security Proof

The security of LLAKEP in the ROR model is shown in Theorem 1.

Theorem 1.

Let be the advantage of a polynomial-time t adversary in breaking the security of LLAKEP, then

where and are the number of queries, the number of queries, the number of queries, the size of password dictionary D in LLAKEP, and the advantage of in breaking the ECDDHP in time t, respectively.

Proof.

Let , where , be a sequence of games, and be the event that an adversary wins the game , the probability of which is denoted by . Those five games are defined as follows:

- This game models the original protocol LLAKEP in the ROR model, and an unbiased coin b is filpped. Therefore,

- This game excludes the eavesdropping attacks. may use the query in this game, and once the instance is accepted, proceeds to the query. In LLAKEP, and are calculated as where For getting the session key, needs ephemeral secrets and the permanent secret identity . Hence, has no advantage in winning the game through eavesdropping attack. Therefore,

- This game models the and queries. may mount an active attack to intercept messages , , and Note that all these messages involve the random nonces and the current timestamps, the only advantage can take is making the queries to find collisions. Therefore, by the birthday paradox,

- This game models the query wherein can extract all the credentials and C from a lost or stolen device or a microprocessor chip, where and Note that since could not get the secret crentials and using the queries, guessing is the only way to obtain the password and identity of a registered user from , v, and C. Therefore,

- : This game models an active attack. To derive the session key SK of and , may use queries to obtain all the intercepted messages , and , and then try to derive . Note that can derive or . However, this problem is essentially the same as solving an ECDDHP. Therefore,

After executing the games, guesses the bit b:

According to (1) and (2), we have:

According to (6) and (7), we have:

Using the triangular inequality, we have the following result:

From (8) and (9), we have:

Then, we obtain the required result:

Theorem 1 is proved. □

6.2. GNY Logic Proof

We introduce the symbols and meanings used in the GNY logic [29] in Table 7, and then prove the mutual authentication between electric bike rider and battery swap station in LLAKEP.

Table 7.

GNY Expression.

6.2.1. Protocol Paraphrase

LLAKEP consists of the following messages between and .

1.

2.

3.

6.2.2. Description of Protocol

The parser algorithm would describe the protocol as follows.

6.2.3. Goal

We need to show that LLAKEP achieves the following goals.

6.2.4. Initialization Assumption

The initialization assumptions for and are as follows.

6.2.5. Proof

The proof of the goals are as follows.

According to rules T1 and P1, we can infer that possesses , and possesses .

Goal 1 According to A1 and the rule F1, we can infer that believes that is fresh, and .

According to the rule F1, we can infer that believes that is fresh, and . Goal 1 is proved.

Goal 2 According to A2 and the rule R1, we can infer that believes that is recognizable, and .

According to the rule R1, we can infer that believes that is recognizable, and . Goal 2 is proved.

Goal 3 According to the rule P2, we can infer that possesses , and .

According to A3 and the rule P2, we can infer that possesses R, and .

According to A3 and the rule P2, we can infer that possesses .

According to the rule F1, we can infer that believes that R is fresh, and .

According to the rule F1, we can infer that believes that is fresh.

According to A4 and the rule I3, we can infer that believes that once said .

According to the rule I6, we can infer that believes that possesses .

According to the rule J6, we can infer that believes that possesses , and . Goal 3 is proved.

Goal 4 According to A5 and the rule F1, we can infer that believes that is fresh, and .

According to the rule F1, we can infer that believes that is fresh, and . Goal 4 is proved.

Goal 5 According to A6 and the rule R1, we can infer that believes that is recognizable, and .

According to the rule R1, we can infer that believes that is recognizable, and . Goal 5 is proved.

Goal 6 According to A7 and the rule P2, we can infer that possesses and R, and .

According to the rule P2, we can infer that possesses , and .

According to A7 and the rule P2, we can infer that possesses .

According to the rule P2, we can infer that possesses .

According to the rule F1, we can infer that believes that R is fresh, and .

According to the rule F1, we can infer that believes that is fresh.

According to A8 and the rule I3, we can infer that believes that once said .

According to the rule I6, we can infer that believes that possesses . Goal 6 is proved.

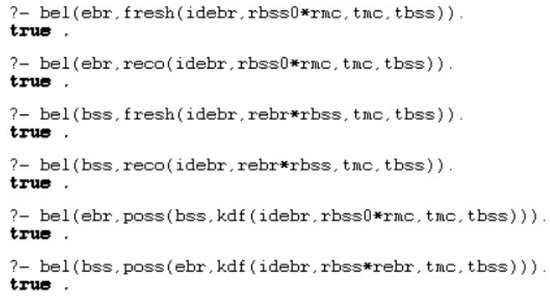

6.3. Formal Verification

We use Prolog to verify that our protocol achieves the session key security goals (the freshness and the recognizability of the session key, and the belief that the two authenticating parties have the session key). Prolog is a logic verification tool. Write the flow of the protocol as Prolog code, and Prolog can verify whether the protocol achieves our required security goals.

The execution results of Prolog are shown in Figure 2, and we can see that several security goals regarding the protocol returned “True”, which indicates that the LLAKEP can achieve the required security goals.

Figure 2.

Prolog verification results of the LLAKEP.

7. Performance Analysis

We mainly analyze the advantages of the LLAKEP and provide a use case of LLAKEP in this section. Furthermore, we test the computation time, the total running time and the bit rate of different protocols. The experimental environment is shown in Table 8. We use to represent the time of running A on device D.

Table 8.

Experiment devices and environments.

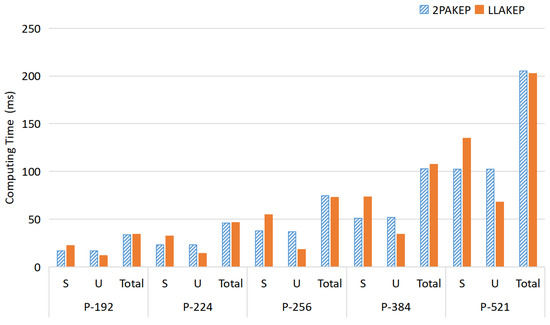

7.1. Experiment I

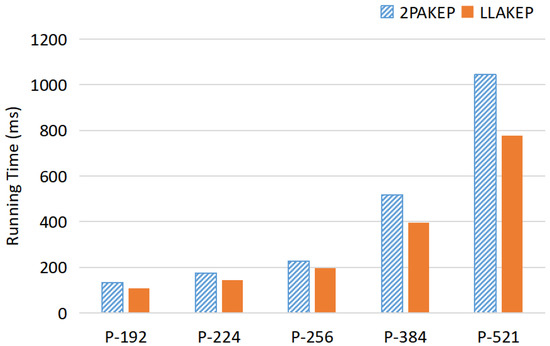

We use two identically configured laptops to represent the correspondents of the LLAKEP and test under the elliptic curves recommended by the National Institute of Standards and Technology Federal Information Processing Standard [30] (i.e., curves P-192, P-224, P-256, P-384, and P-521). From Figure 3, the following are some verified results:

Figure 3.

Average computing time in Experiment I. The experiment uses two identically configured laptops to represent two parties of the LLAKEP. The results are as follows: (1) the calculation time on the U side using LLAKEP is less than 2PAKEP; (2) LLAKEP does reduce the computational burden on the EBR’s side.

For the average computing time on the side:

The results show that LLAKEP does reduce the computational burden on the EBR’s side.

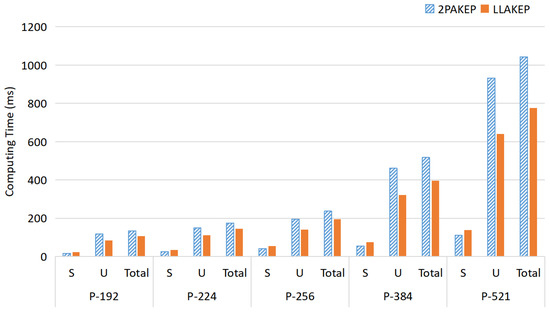

7.2. Experiment II

We use a Raspberry Pi to represent the smart glasses and a laptop to represent the energy device. Smart glasses have less computing capability than laptops. We test LLAKEP under the same conditions as the elliptic curve of Experiment I. From Figure 4, the following are some verified results:

Figure 4.

Average computing time in Experiment II. The experiment uses a Raspberry Pi to represent the smart glasses and a laptop to represent the energy device. The results are as follows: (1) the calculation time on the U side using LLAKEP is less than 2PAKEP; (2) the total calculation time of LLAKEP is less than 2PAKEP.

- For the average computing time on the side:

- For the average total computing time:

It shows that the weaker device (i.e., smart glasses) in LLAKEP has shorter computation time. Further, LLAKEP has shorter total computation time compared with 2PAKEP.

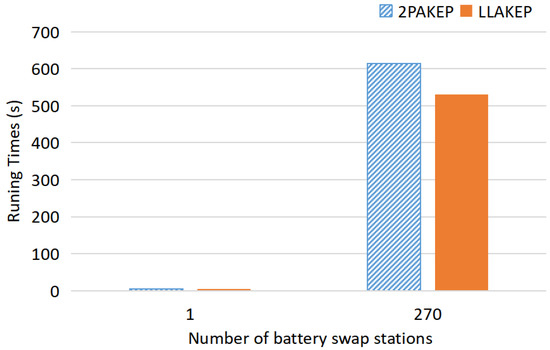

7.3. Experiment III

This experiment measures the total running time of LLAKEP on two communicating parties (a Raspberry Pi and a laptop). From Figure 5, the following are some verified results:

Figure 5.

Average total runing time in Experiment III. The experiment uses a Raspberry Pi and a laptop to measure the total running time of LLAKEP. The results show that LLAKEP has shorter total running time compared with 2PAKEP.

For the average total time:

The results show that LLAKEP still has shorter total running time compared with 2PAKEP.

7.4. Experiment IV

We assume bits of different messages in Table 9.

Table 9.

Bits of different messages.

Therefore, in the authentication phase of the LLAKEP, needs (160 + 160 + 160 + 32) = 512 bits, needs (160 + 320 +32) = 512 bits and needs (160 + 32) = 192 bits. The total bits of LLAKEP is 1216 bits. Combining the total runtime of the protocol in Experiment III with the elliptic curve P-256, we can calculate the bit rate. The higher the bit rate, the faster the data transfer speed. The results are shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Bit rate comparison.

For the bit rate :

Therefore, the transmission latency of LLAKEP is lower.

7.5. Experiment V: Use Case Study

This section illustrates usages and advantages of LLAKEP via a use case in a batterty swap cabinets scenario.

7.5.1. Scenario Description

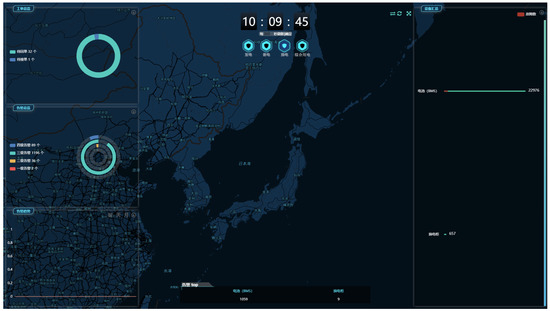

At present, there are more than 300 million electric bikes in China. In order to meet a large number of battery swap needs, China Tower has built an intelligent power exchange system. They have also deployed battery swap stations (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Battery swap cabinet.

In the future, with the development of the Metaverse, electric bike riders will use smart glasses to interact with battery swap cabinets. During the peak period, a large number of riders will need to authenticate and pay at the same time.

7.5.2. Application of LLAKEP

The following steps explain how we can use LLAKEP.

Initialization: devices A and B should support LLAKEP. Specifically, device A is smart glasses; device B is a battery swap cabinet.

Secure Handshake: suppose there are N smart glasses in the battery swap cabinet scenarios.

Secure Messaging: A and B use the generated session key to send the message (battery type and payment information) securely.

7.5.3. Advantages

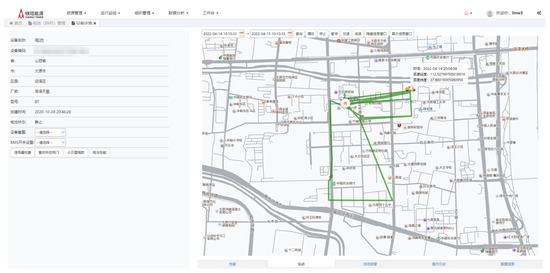

In this part, we analyze the advantages of LLAKEP. According to the statistics from the battery swap station management system (Figure 7 and Figure 8), the number of battery swap stations in Taiyuan city is 270. One battery swap station has 10 battery swap cabinets. In the peak time, 2700 riders use smart glasses to authenticate. After successful authentication, the rider will pay for the swap of a battery. Taking P-256 as an example, Figure 9 shows the authentication protocol running time of battery swap stations in the peak time. Experiment results show that LLAKEP can reduce latency effectively.

Figure 7.

Battery swap station management system. The number of battery swap stations in Taiyuan city can be obtained from this system.

Figure 8.

Battery management system (BMS). The usage state of the battery can be obtained from this system.

Figure 9.

Runing time in Experiment IV. The experiment tests the total running time of all the batteries of 270 battery swap stations in the authentication phase. The results show that the total running time of LLAKEP is significantly less than 2PAKEP.

8. Conclusions

This paper proposes a secure, low-latency authentication protocol LLAKEP for the EIoT. LLAKEP reduces the computational burden on weaker devices by changing the time-consuming cryptographic operations needed in the algorithms for both sides of communication. In addition, a provable security model and a logic analysis are used to analyze LLAKEP. Results show that the security of LLAKEP is guaranteed. When the computing capability of both parties is unbalanced, experimental results show that LLAKEP can reduce the computing time of the device with weaker computing capability. It can improve the efficiency of authentication. Finally in the use case, we apply LLAKEP for EIoT electricity transaction system in the Metaverse.

In the future, we will continue to optimize the low-latency algorithm, and design more low-latency AKE protocols suitable for Metaverse scenarios.

Author Contributions

Methodology, X.Z.; formal analysis, X.Z., H.Y. and J.H.; investigation, X.Z.; resources, S.C., B.X., X.W. and L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z., X.H. and H.Y.; writing—review and editing, X.Z., X.H. and H.Y.; project administration, X.H.; funding acquisition, X.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Project Shanxi Scholarship Council of China 2021-038, and the Applied Basic Research Project of Shanxi Province No. 20210302123130.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shamir, A. Identity-based cryptosystems and signature schemes. In Workshop on the Theory and Application of Cryptographic Techniques; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; pp. 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ometov, A.; Bezzateev, S.; Mäkitalo, N.; Andreev, S.; Mikkonen, T.; Koucheryavy, Y. Multi-factor authentication: A survey. Cryptography 2018, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, D.; Wang, P. Offline dictionary attack on password authentication schemes using smart cards. In Information Security; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 221–237. [Google Scholar]

- Ah Kioon, M.C.; Wang, Z.S.; Deb Das, S. Security analysis of MD5 algorithm in password storage. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 347, 2706–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heartfield, R.; Loukas, G. A taxonomy of attacks and a survey of defence mechanisms for semantic social engineering attacks. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2015, 48, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petsas, T.; Tsirantonakis, G.; Athanasopoulos, E.; Ioannidis, S. Two-factor authentication: Is the world ready? Quantifying 2FA adoption. In Proceedings of the Eighth European Workshop on System Security, Bordeaux, France, 21 April 2015; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; He, D.; Wang, P.; Chu, C.H. Anonymous two-factor authentication in distributed systems: Certain goals are beyond attainment. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2014, 12, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolfaei, A.; Kant, K. A lightweight integrity protection scheme for low latency smart grid applications. Comput. Secur. 2019, 86, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahmood, K.; Chaudhry, S.A.; Naqvi, H.; Kumari, S.; Li, X.; Sangaiah, A.K. An elliptic curve cryptography based lightweight authentication scheme for smart grid communication. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 81, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.H.; Braud, T.; Zhou, P.; Wang, L.; Xu, D.; Lin, Z.; Kumar, A.; Bermejo, C.; Hui, P. All one needs to know about metaverse: A complete survey on technological singularity, virtual ecosystem, and research agenda. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2110.05352. [Google Scholar]

- Ynag, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, H.; Zheng, Z. Fusing Blockchain and AI with Metaverse: A Survey. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.03201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.L.; Saxena, A.; Gulati, V.P.; Phatak, D.B. A novel remote user authentication scheme using bilinear pairings. Comput. Secur. 2006, 25, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H.; Chang, C.C. An ID-based remote mutual authentication with key agreement scheme for mobile devices on elliptic curve cryptosystem. Comput. Secur. 2009, 28, 138–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, E.J.; Yoo, K.Y. Robust id-based remote mutual authentication with key agreement scheme for mobile devices on ECC. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Computational Science and Engineering, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 29–31 August 2009; Volume 2, pp. 633–640. [Google Scholar]

- Debiao, H.; Jianhua, C.; Jin, H. An ID-based client authentication with key agreement protocol for mobile client–Server environment on ECC with provable security. Inf. Fusion 2012, 13, 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Chen, J. An efficient two-party authentication key exchange protocol for mobile environment. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2017, 30, e3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Park, Y.; Park, Y.; Das, A.K. 2PAKEP: Provably secure and efficient two-party authenticated key exchange protocol for mobile environment. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 30225–30241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goriparthi, T.; Das, M.L.; Negi, A.; Saxena, A. Cryptanalysis of recently proposed Remote User Authentication Schemes. IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2006, 2006, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, C.H.; Tsai, K.Y.; Lu, C.F. Two ID-based authenticated schemes with key agreement for mobile environments. J. Supercomput. 2013, 66, 973–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y. An improved two-party authentication key exchange protocol for mobile environment. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2015, 85, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, S.; Hu, J.; Zheng, G.; Chaudhry, J.; Adi, E.; Valli, C. Securing mobile healthcare data: A smart card based cancelable finger-vein bio-cryptosystem. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 36939–36947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Song, C.; Cao, N.; Li, Z.; Zhou, W.; Chen, J.; Meng, L. A new mutual authentication protocol in mobile RFID for smart campus. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 60996–61005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouqi, C.; Wanrong, L.; Liling, C.; Xin, H.; Zhiyong, J. An improved authentication protocol using smart cards for the Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 157284–157292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Qin, Y.; Yang, B.; Feng, D. Trusttokenf: A generic security framework for mobile two-factor authentication using trustzone. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Trustcom/BigDataSE/ISPA, Helsinki, Finland, 20–22 August 2015; Volume 1, pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Koutroumpouchos, N.; Ntantogian, C.; Xenakis, C. Building Trust for Smart Connected Devices: The Challenges and Pitfalls of TrustZone. Sensors 2021, 21, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasser, F.; Kim, D.; Liebchen, C.; Ganapathy, V.; Iftode, L.; Sadeghi, A.R. Regulating arm trustzone devices in restricted spaces. In Proceedings of the 14th Annual International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services, Singapore, 26–30 June 2016; pp. 413–425. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla, M.; Fouque, P.A.; Pointcheval, D. Password-based authenticated key exchange in the three-party setting. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Public Key Cryptography, Les Diablerets, Switzerland, 23–26 January 2005; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Bellare, M.; Pointcheval, D.; Rogaway, P. Authenticated key exchange secure against dictionary attacks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Bruges, Belgium, 14–18 May 2000; pp. 139–155. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, L.; Needham, R.M.; Yahalom, R. Reasoning about Belief in Cryptographic Protocols. In Proceedings of the 1990 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, Oakland, CA, USA, 7–9 May 1990; pp. 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standard, S.H. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) 186-4. 2013. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/publications/detail/fips/186/4/final (accessed on 19 July 2013).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).