1. Introduction

Speech Emotion Recognition (SER) systems are currently being intensively used in a broad range of applications, including security, healthcare, videogaming, mobile communications, etc. [

1]. The development of SER systems has been a hot topic of research in the field of human-computer interaction for the past two decades. Most of these studies are focused on emotion recognition from adult speech [

2,

3,

4,

5], and only a few are from children’s speech [

6,

7,

8,

9]. This follows from the fact that sizable datasets of children’s speech with annotated emotion labels are still not publicly available in the research community, which leads most researchers to focus on SER for adults.

The reason is that it is difficult to get a wide range of emotional expressions in children’s speech due to the following. Children, especially those of primary school age, find it difficult to pronounce and read long texts, and it is more difficult for children than adults to express emotions in acting speech if a child has not experienced these emotions before. School-age children commonly demonstrate a limited range of emotions when interacting with unfamiliar adults due to differences in social status and with regard to training. Generally, children show vivid emotions when interacting with peers, but this situation is usually accompanied by strong noise and overlapping voices. Due to ethical standards, the provocation of vivid negative emotions, such as fear, sadness and anger should be allowed by an informed consent to be signed by the parents. However, not all of them are ready to provide such consent.

However, children are potentially the largest class of users of educational and entertainment applications with speech-based interfaces.

The characteristics of a child’s voice are significantly different from those of an adult’s voice. The child’s voice’s clarity and consistency of speech are low compared to an adult [

10], while acoustic and linguistic variability in children’s speech is high, which creates challenges for emotion recognition. Another severe problem is the paucity of publicly available transcribed linguistic resources for children’s speech. Moreover, research on SER faces the problem that most available speech corpora differ from each other in important ways, such as methods of annotation and scenarios of interaction [

11,

12,

13]. Inconsistencies in these methods and scenarios make it difficult to build SER systems.

All of the above-mentioned problems make the task of developing automatic emotion recognition in children’s speech non-trivial, especially taking into account variations of acoustic features within genders, age groups, languages, and developmental characteristics [

14]. For example, the authors of [

15] report that the average accuracy of emotional classification is 93.3%, 89.4% and 83.3% for male, female, and child utterances, respectively.

Our analysis of databases of children’s emotional speech created over the past 10 years has shown that they cover mainly monolingual emotional speech in such languages as English, Spanish, Mexican Spanish, German, Chinese, and Tamil. The only database of children’s emotional speech in Russian is EmoChildRu [

16], which was used to study manifestations of the emotional states of three- to seven-year-old children in verbal and non-verbal behavior [

17].

Children of three to seven years of age were selected for their ability to maintain a communication with an adult while expressing more pure natural emotions than older children. The socialization of children in accordance with cultural norms and traditions mostly begins with schooling which, in the Russian Federation, starts at six to seven years old. This period characterizes the end of the preschool age.

Nevertheless, other databases we have analyzed consist mostly of children’s speech of the younger school age group. The particular qualities of the primary school children are, on the one hand, the partial mastery of accepted cultural norms of emotional manifestations; while on the other hand, they represent the presence of natural spontaneous emotional manifestations characteristic of children of this age.

It is highlighted in [

18] that the expansion of existing corpora of child-machine communications is necessary for building more intricate emotional models for advanced speech interactive systems designed for children. These new corpora can include other languages and age groups, more subjects, etc. Therefore, our recent works have included the collecting of children’s emotional speech of younger school age (8–12-year-olds) in the Russian language, as studies of children’s emotion recognition by voice and speech in Russian are sparse, especially for the younger school age group.

There are several key features of our corpus. Firstly, this is the first large-scale corpus dealing with Russian children’s speech emotions, which includes around 30 h of speech. Secondly, there are 95 speakers in this corpus. Such a large number of speakers makes it possible to research techniques for speaker-independent emotion recognition and analysis. To validate the dataset [

19,

20], a subset of 33 recordings was evaluated by 10 Russian experts [

21] who conducted manual tests to understand how well humans identify emotional states in the collected dataset of emotional speech of Russian speaking children. Results of manual evaluation validate the database reliability compared with other databases and the ability of native-speaking experts to recognize emotional states in children’s speech in the Russian language with above chance performance.

In this article we report the results of experiments on SER conducted using our proprietary database and state-of-the-art machine learning (ML) algorithms. Such experiments are usually conducted to validate the ability to recognize emotional states in children’s speech on specific databases in automatic mode with above chance performance. The article presents the results of the experiments and compares them both with results of SER in manual mode and results of SER in automatic mode from other authors for the same age group and the same ML algorithms.

It is noted in [

22] that neural networks and Support Vector Machine (SVM) behave differently, and each have advantages and disadvantages for building a SER; however, both are relevant for the task. Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) is the “basic” example of a neural network. Therefore, to get a general impression of our dataset, we conducted baseline speech emotion recognition experiments using two of the state-of-the-art machine learning techniques most popular in emotion recognition, these being SVM and MLP [

23,

24]. These classifiers have already been used to validate several databases of emotional speech [

25] and have shown superior classification accuracy on small-to-medium size databases.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

An extended description of the Russian Younger School Children Emotional Speech (SCES-1) database is provided.

Validation of the SCES-1 dataset in automatic mode based on SVM and MLP algorithms to recognize above chance emotional states in the speech of Russian children of the younger school age group (8–12-year-old) is undertaken.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In

Section 2, the various existing corpora and both features and classifiers used in the literature for SER are discussed.

Section 3 provides a detailed description of our proprietary dataset. In

Section 4 we define the experimental setup describing our choice of tools to extract feature sets, tools to implement classifiers and evaluate the results of classification and procedures for training and testing. In

Section 5, we provide the experimental results. Finally,

Section 6 presents the discussion and conclusions, and topics for future research are discussed.

2. Related Work

There are a lot of studies on emotion manifestations in the voice and other biometric modalities. Recently, attention to research on automatic methods of emotion recognition in speech signals has increased due to the development of new efficient methods of machine learning, the availability of open access corpora of emotional speech and high-performance computing resources.

In the last decade, many SER systems have been proposed in the literature. There are numerous publications and reviews on three traditional SER issues: databases, features, and classifiers. Swain et al. [

11] reviewed studies on SER systems in the period from 2000 to 2017 with a strong emphasis on databases and feature extraction. However, only traditional machine learning methods were considered as a classification tool, and the authors missed neural networks and deep learning approaches. The authors of [

26] covered all the major deep learning techniques used in SER, from DNNs to LSTMs and attention mechanisms.

In this section, we summarize some of the most relevant recent research on SER, focusing on children’s speech. In doing so, we pay special attention to those approaches that use the same feature extraction (FE) and machine learning (ML) methods used in this article.

2.1. Children’s Emotion Speech Corpora

Over the past three decades, many emotional datasets and corpora have been created in audio or audiovisual modalities [

12,

26,

27,

28]. Some of them are related to natural emotions (spontaneous emotions from real-life situations), while others are related to acted (simulated, for example, by actors) or elicited (induced/stimulated through emotional movies, stories, and games) emotions. Spontaneous emotions are preferable, but they are difficult to collect. Therefore, most of the available emotional speech corpora contain acted emotional speech. Moreover, the emotional corpora are mainly related to adult speech.

Corpora related to children’s speech have also been created over the past three decades [

29], but they are not so numerous, and only a few of them are related to children’s emotional speech. Most of the corpora are in the English language, but some of them are in the German, French, Spanish, Mandarin, Sesotho, Filipino, and Russian languages. Moreover, these corpora vary not only by language but also by children’s age range, different specific groups like specific language impairment [

30], autism spectrum disorder [

31], etc.

We briefly describe the eight most famous corpora with children’s emotional speech in

Table 1.

MESD (Mexican Emotional Speech Database) [

15,

32], presented in 2021. A part of the MESD with children’s speech has been uttered by six non-professional actors with mean age of 9.83 years and a standard deviation of 1.17. The database contains 288 recordings of children’s speech with six different emotional categories: Anger, Disgust, Fear, Happiness, Sadness, and Neutral. The results of the evaluation of the database reliability based on machine learning analysis showed the accuracy of 83.3% of emotion recognition on children’s voices. An SVM was used as a classifier together with a feature set with prosodic, voice quality and spectral features. MESD is considered a valuable resource for healthcare, as it can be used to improve diagnosis and disease characterization.

IESC-Child (Interactive Emotional Children’s Speech Corpus) [

18], presented in 2020. A Wizard of Oz (WoZ) setting was used to induce different emotional reactions in children during speech-based interactions with two Lego Mindstorm robots behaving either collaboratively or non-collaboratively. The IESC-Child corpus consists of recordings of the speech spoken in Mexican Spanish by 174 children (80 girls and 94 boys) between six and 11 years of age (8.62 mean, 1.73 standard deviation). The recordings included 34.88 h of induced speech. In total, eight emotional categories are labeled: Anger, Disgust, Fear, Happiness, Sadness, Surprise, Neutral, and None of the above. The research on building acoustic paralinguistic models and speech communication between a child and a machine in Spanish utilized the IESC-Child dataset with prominent results.

EmoReact (Multimodal Dataset for Recognizing Emotional Responses in Children) [

33], presented in 2016. A multimodal spontaneous emotion dataset of 63 (31 males, 32 females) children ranging between four and 14 years old. It was collected by downloading videos of children who react to different subjects such as food, technology, YouTube videos and gaming devices. The dataset contains 1102 audio-visual clips annotated for 17 different emotional categories: six basic emotions, neutral, valence and nine complex emotions.

CHEAVD (Chinese Natural Emotional Audio–Visual Database) [

34], presented in 2016. A large-scale Chinese natural emotional audio–visual corpus with emotional segments extracted from films, TV plays and talk shows. The corpus contains 238 (125 males, 113 females) speakers from six age groups: child (<13), adolescent/mutation (13–16), youth (16–24), young (25–44), quinquagenarian (45–59), and elder (≥60). Over 141 h of spontaneous speech was recorded. In total, 26 non-prototypical emotional states, including the basic six, are labeled by four native speakers.

EmoChildRu (Child emotional speech corpus in Russian) [

16,

17], presented in 2015. This contains audio materials from 100 children ranging between three and seven years old. Recordings were organized in three model situations by creating different emotional states for children: playing with a standard set of toys; repetition of words from a toy-parrot in a game store setting; watching a cartoon and retelling the story, respectively. Over 30 h of spontaneous speech were recorded. The utterances were annotated for four emotional categories: Sadness, Anger, Fear, Happiness (Joy). The data presented in the database are important for assessing the emotional development of children with typical maturation and as controls for studying emotions of children with disabilities.

ASD-DB (Autism Spectrum Disorder Tamil speech emotion database) [

35], presented in 2014. This consists of spontaneous speech samples from 25 (13 males, 12 females) children ranging between five and 12 years old with autism spectrum disorder. The children’s voices were recorded in a special school (open space) using a laptop with a video camera. Recordings were taken in wav format at a sampling rate 16,000 Hz and a quantization of 16 bits. The emotion categories included Anger, Neutral, Fear, Happiness, and Sadness. The database was validated using MFCC features and an SVM classifier.

EmoWisconsin (Emotional Wisconsin Card Sorting Test) [

36], presented in 2011. This contains spontaneous, induced and natural Spanish emotional speech of 28 (17 males, 11 females) children ranging between 7 and 13 years old. The collection was recorded in a small room with little noise using two computers, a desktop microphone and a Sigmatel STAC 9200 sound card. Recordings are mono channel, with 16 bit sample size, 44,100 kHz sample rate and stored in WAV Windows PCM format. We recorded 11.38 h of speech in 56 sessions, two sessions per child over seven days. The total number of utterances was 2040, annotated for seven emotional categories: Annoyed, Confident, Doubtful, Motivated, Nervous, Neutral, and Undetermined. For the database validation based on categorical classification we used an SVM algorithm with 10-fold cross validation. The results of the validation showed a performance above chance level comparable to other publicly available databases of affective speech such as VAM and IEMOCAP.

FAU-AIBO (Friedrich-Alexander-Universität corpus of spontaneous, emotionally colored speech of children interacting with Sony’s pet robot Aibo) [

37,

38], presented in 2006. The corpus was collected from the recordings of children interacting with Sony’s pet robot Aibo. It consists of spontaneous, emotionally colored German/English speech from 51 children (21 males, 30 females) ranging between 10 and 13 years old. The total number of utterances is 4525 with a total duration of 8.90 h. The audio was recorded by using a DAT recorder (16-bit, 16 kHz). Five annotators labeled each word individually as Neutral (default) or using one of the other ten emotions: Angry, Bored, Joyful, Surprised, Emphatic, Helpless, Touchy (=Irritated), Motherese, Reprimanding, Rest (non-Neutral, but not belonging to the other categories). The final label was defined using the majority voting procedure. For the database validation based on classification we used a neural network. The results of validation showed that the performance of speech emotion classification on the FAU-AIBO corpora is above chance level.

The results of the analysis of the available children’s emotion speech corpora show that they are all monolingual. The corpora contain mainly emotional speech of the school age group, with the exception of EmoChildRu (preschool age group) and CHEAVD (adolescence and adult age groups). All of the corpora were validated using manual perceptual tests and/or automatic SVM/MLP classifiers with different feature sets. The results of validation showed that performance of speech emotion classification on all the corpora is well above chance level.

2.2. Speech Emotion Recognition: Features and Classifiers

The classic pattern recognition task can be defined as the classification of patterns (objects of interest) based on information (features) extracted from patterns and/or their representation [

39]. As noted in [

40], a selection of suitable feature sets, design of proper classification methods and preparation of appropriate datasets are the key concerns of SER systems.

In the feature-based approach to emotion recognition, we assume that there is a set of objectively measurable parameters in speech that reflect the emotional state of a person. The emotion classifier identifies emotion states by identifying correlations between emotions and features. For SER, many feature extraction and machine learning techniques have been extensively developed in recent times.

2.2.1. Features

Selecting the best feature set powerful enough to distinguish between different emotions is a major problem when building SER systems. The power of the selected feature set has to stay stable in the presence of various languages, speaking styles, speaker’s characteristics, etc. Many models for predicting the emotional patterns of speech are trained on the basis of three broad categories of speech features: prosody, voice quality, and spectral features [

5].

In emotion recognition the following types of features are found to be important:

Acoustic features of prosodic: pitch, energy, duration.

Spectral features: MFCC, GFCC, LPCC, PLP, formants.

Voice quality features: jitter, shimmer, harmonics to noise ratio, normalized amplitude quotient, quasi-open quotient.

Most of the well-known feature sets include pitch, energy and their statistics, which are widely used in expert practice [

21].

For automatic emotion recognition, we have used three publicly available feature sets:

INTERSPEECH Emotion Challenge set (IS09) [

41] with 384 features. It was found that the IS09 feature set provides good performance of children’s speech emotion recognition. Nevertheless, we conducted some experiments with other feature sets.

Geneva Minimalistic Acoustic Parameter Set (GeMAPS) and the extended Geneva Minimalistic Acoustic Parameter Set (eGeMAPS). They are popular in the field of affective computing [

42]. The GeMAPS family features include not only prosody but also spectral and other features. The total GeMAPS v2.0.0 feature set contains 62 features and the eGeMAPSv02 feature set contains 26 extra parameters, for a total of 88 parameters.

DisVoice feature set. This is a popular feature set that has shown good performance in such tasks as recognition of emotions and communication capabilities of people with speech disorders and issues such as depression based on speech patterns [

43]. The DisVoice feature set includes glottal, phonation, articulation, prosody, phonological, and features representation learning strategies using autoencoders [

43]. It is well known that prosodic and temporal characteristics have often been used previously to identify emotions [

5]. Therefore, our next experiments were with the DisVoice prosody feature set.

2.2.2. Classifiers

Many different classification methods are used to recognize emotions in speech. There are a lot of publications on using different classifiers in SER [

23,

25]. The most popular are classical machine learning (ML) algorithms, such as Support Vector Machines (SVM), Hidden Markov Models (HMM), Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM), Neural Networks (NN), and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) as the “basic” example of NN. Currently, we see the massive application of deep learning (DL) in different fields, including SER. DL techniques that are used to improve SER performance may include Deep Neural Networks (DNN) of various architectures [

26], Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) [

44,

45], autoencoders [

46,

47], Extreme Learning Machines (ELM) [

48], multitask learning [

49], transfer learning [

50], attention mechanisms [

26], etc.

The choice of a classification algorithm depends mainly on the properties of the data (e.g., number of classes), as well as the nature and number of features. Taking into account the specifics of children’s speech, we must choose a classification algorithm that could be effective in multidimensional spaces on a relatively small-to-medium database size and with low sensitivity to outlier values.

The analysis of the literature shows that the best candidates are SVM and MLP classifiers, where SVM is a deterministic and MLP is a non-deterministic supervised learning algorithm for classification. SVM and MLP are baseline classifiers in numerous studies on emotion speech recognition.

First of all, traditional ML algorithms could provide reliable results in the case of small-to-medium size of training data [

51,

52,

53]. Second, SVM and MLP classifiers often demonstrate better performance than others [

22,

23,

54]. Some experiments have shown a supercity of SVM and MLP for emotion recognition over classical Random Forest, K-NN, etc. classifiers [

54] and also over different deep neural network classifiers [

55]. The failure of neural network classifiers in emotion recognition can be explained by the small size of available emotional databases, which are insufficient for training deep neural networks.

We chose to work with an SVM model to evaluate the validity of an emotional database, as it is capable of producing meaningful results with small-to-medium datasets (unlike algorithms such as deep neural networks) and its ability for handling high-dimensional spaces [

1]. In [

55], it was shown that the SVM classifier outperforms Back Propagation Neural Networks, Extreme Learning Machine and Probabilistic Neural Networks by 11 to 15 percent, reaching 92.4% overall accuracy. In [

56] it was also shown that SVM works systematically better than Logistic Regression and LSTM classifiers on the IS09 Emotion dataset.

MLP is the “basic” example of NN. It is stated in [

22] that MLP is the most effective speech emotion classifier, with accuracies higher than 90% for single-language approaches, followed closely by SVM. The results show that MLP outperforms SVM in overall emotion classification performance, and even though SVM training is faster compared to MLP, the ultimate accuracy of MLP is higher than that of SVM [

57]. SVM has a lower error rate than other algorithms, but it is inefficient if the dataset has some noise [

57].

The use of SVM and MLP classifiers allows us to compare the performance of emotion recognition on our database with the performance of the same classifiers on other known databases of children’s emotional speech.

Moreover, the results of classification by SVM and MLP can be used as a baseline point for comparison with other models, such as deep neural networks (CNN, RNN, etc.), to see if they provide better performance for SER.

3. Corpus Description

To study emotional speech recognition of Russian typically developing children aged 8–12 years by humans and machines, a language-specific corpus of emotional speech was collected. The corpus contains records of spontaneous speech and acting speech of 95 children with the following information about children: age, place and date of birth, data on hearing thresholds (obtained using automatic tonal audiometry), phonemic hearing and videos with facial expressions and the behavior of children.

3.1. Place and Equipment for Speech Recording

The place for speech recording was the room without special soundproofing.

Recordings of children’s speech were made using a Handheld Digital Audio Recorder PMD660 (Marantz Professional, inMusic, Inc., Sagamihara, Japan) with an external handheld cardioid dynamic microphone Sennheiser e835S (Sennheiser electronic GmbH & Co. KG, Beijing, China). In parallel with the speech recording, the behavior and facial expressions of children were recorded using a video camera Sony HDR-CX560E (SONY Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Video recording was conducted as part of studies on the manifestation of emotions in children’s speech [

16] and facial expressions [

58].

The distance from the child’s face to the microphone was in the range of 30–50 cm. All children’s speech and video recordings were included in the corpus. All speech files were saved in .wav format, 48,000 Hz, 16 bits per sample. For each child, the recording time was in the range of 30–40 min.

3.2. Speech Recording Procedure

Two types of speech were recorded—natural (spontaneous) speech and acting speech.

Dialogue between the children and the experimenters were used to obtain recordings of the children’s natural speech. We hypothesized that semantically different questions could induce different emotional states in children [

26]. A standard set of experimenter’s questions addressed to the child was used. The experimenter began the dialogue with a request for the child to tell his/her name and age. Further questions included:

What lessons at school do you like and why?

Who are your friends at school?

What do you play at breaks between lessons?

What are your hobbies?

What movies and cartoons do you like to watch?

Can you remember are funny stories?

Which teachers you don’t like and why?

Do you often fight with other children? Are you swearing?

Do you often get angry? What makes you angry?

Do you often get sad? What makes you sad?

Children’s acting speech was recorded after dialogue recording sessions. The children had to pronounce speech material—sets of words, words and phrases, as well as meaningless texts demonstrating different emotional states “Neutral (Calm)—Joy—Sadness—Anger”. Children were trained to pronounce sets of words, words and phrases, as well as meaningless texts. Before recording the acting speech, each child was asked to pronounce the proposed speech material two to three times depending on the age of the child. Children eight to nine years of age had difficulty pronouncing meaningless texts, so they were instructed to practice to fluently read the whole meaningless text out, rather than articulating individual words.

Two experts estimated how well the children could express different emotional states in their vocal expressions during the training and speech recording sessions. The experts asked a child to repeat the text if the child was distracted, showed an emotion that did not correspond to the given task, or made mistakes in the pronunciation of words.

The selection of this list of emotions was based on the assumption [

40] that there is no generally acceptable list of basic emotions, and even though the lists of basic emotions differ, Happiness (Joy, Enjoyment), Sadness, Anger, and Fear appear in most of them. In [

59] it was also noted that categories such as Happiness, Sadness, Anger, and Fear are generally recognized with accuracy rates well above chance. In [

34] it is noted that regarding the emotion category, there is no unified basic emotion set. Most emotional databases address prototypical emotion categories, such as Happiness, Anger and Sadness.

A number of emotion recognition applications use three categories of speech: emotional speech with positive and negative valence, and neutral speech. In practice, collecting and labeling a dataset with such three speech categories is quite easy, since it can be done by naive speakers and listeners rather than professional actors and experts. As an extension of this approach, some SER [

60,

61,

62,

63] use four categories of emotional speech, positive (Joy or Happiness), neutral, and negative (Anger and Sadness). In this case it is also quite easy to collect a dataset, but to label the dataset we need experts.

The set of words and set of words and phrases were selected according to the lexical meaning of words /joy, beautiful, cool, super, nothing, normal, sad, hard, scream, break, crush/ and phrases /I love when everything is beautiful, Sad time, I love to beat and break everything/. The meaningless sentences were pseudo-sentences (semantically meaningless sentences resembling real sentences), used e.g., [

64] to reduce the influence of linguistic meaning. A fragment of “Jabberwocky”, the poem by Lewis Carroll [

65] and the meaningless text (sentence) by L.V. Shcherba “Glokaya kuzdra” [

66] were used. Children had to utter speech material imitating different emotional states “Joy, Neutral (Calm), Sadness, Anger”.

After the completion of the sessions recording the children’s speech, two procedures were carried out: audiometry, to assess the hearing threshold, and a phonemic hearing test (repetition of pairs and triple syllables by the child following the speech therapist).

All procedures were approved by the Health and Human Research Ethics Committee of Saint Petersburg State University (Russia), and written informed consent was obtained from parents of the participating children.

Speech recording was conducted according to a standardized protocol. For automatic analysis, only the acting speech of children was taken.

3.3. Process of Speech Data Annotation

After the raw data selection, all speech recordings are split into segments which contain emotions and are manually checked to ensure audio quality. The requirements for the segments are as follows:

Segments should not have high background noise or voice overlaps.

Each segment should contain only one speaker’s speech.

Each speech segment should contain a complete utterance. Any segment without an utterance was removed.

The acting speech from the database was annotated according the emotional states manifested by children when speaking: “neutral—joy—sadness—anger”. The annotation was made by two experts based on the recording protocol and video recordings. The speech sample is assigned to the determined emotional state if the accordance between two experts is 100%.

2505 samples of acting speech (words, phrases, and meaningless texts) were selected as a result of annotation: 628 for the neutral state, 592 for joy, 646 for sadness, and 639 for anger. In contrast to other existing databases, the distribution of the emotions in our database is approximately uniform.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Our experiments were conducted on our proprietary dataset of children’s emotional speech in the Russian language of the younger school age group [

21]. To our knowledge, this is the only such database.

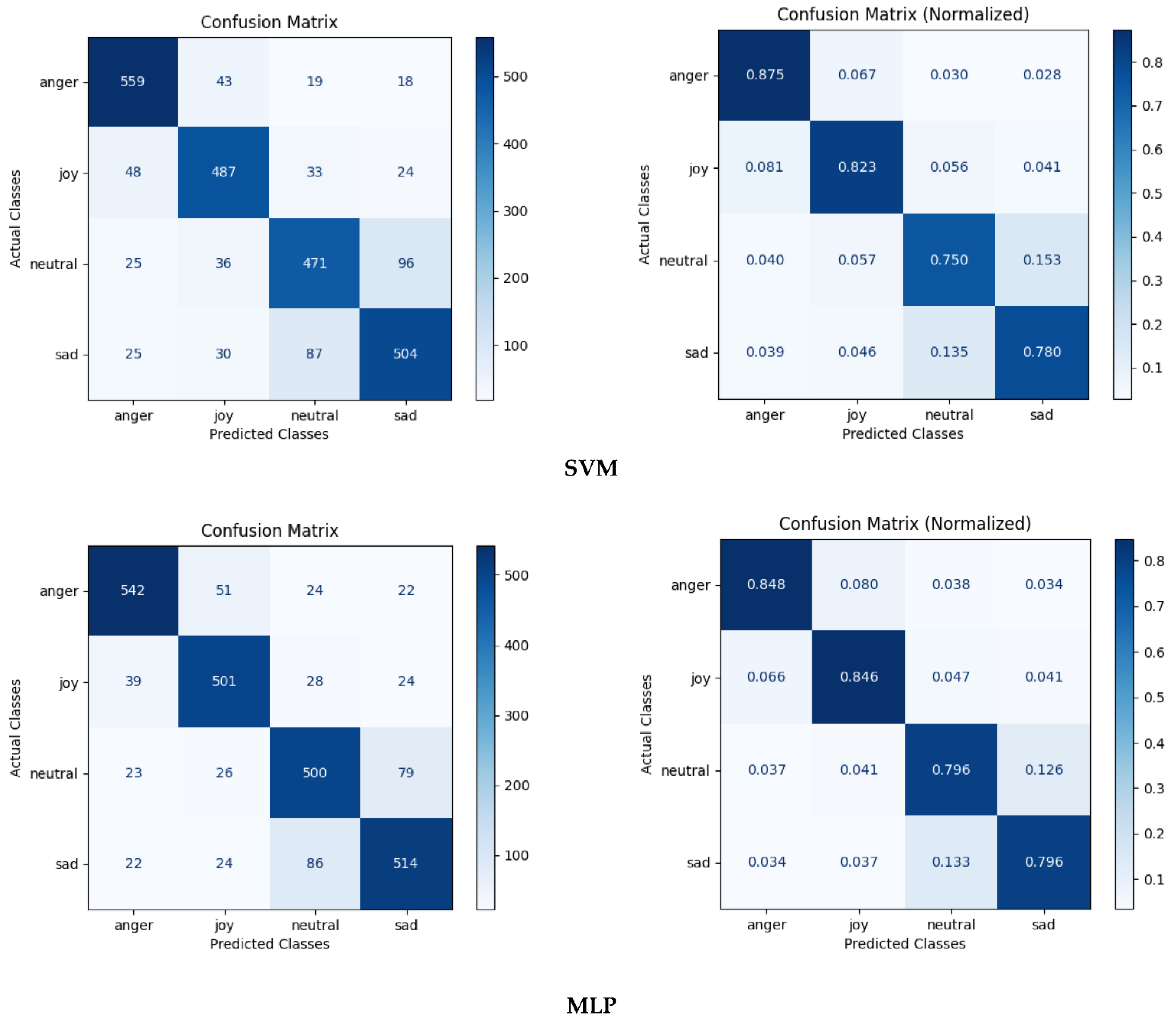

We have conducted a validation of our dataset based on classical ML algorithms, such as SVM and MLP. The validation was performed using standard procedures and scenarios of the validation similar to other well-known databases of children’s emotional speech.

First of all, we demonstrated the following performance of automatic multiclass recognition (four emotion classes): SVM Overall Accuracy = 0.903, UAR = 0.807, and also MLP Overall Accuracy = 0.911, UAR = 0.822 are superior to the results of the perceptual test with Overall Accuracy = 0.898 and UAR = 0.795. Moreover, the results of automatic recognition on the test dataset, which consists of 33 samples used in the perceptual test, are even better: SVM Overall Accuracy = 0.924, UAR = 0.851, and also MLP Overall Accuracy = 0.924, UAR = 0.847. This can be explained by the fact that for the perceptual test we selected samples with clearly expressed emotions.

Second, a comparison with the results of validation of other databases of children’s emotional speech on the same and other classifiers showed that our database contains reliable samples of children’s emotional speech which can be used to develop various edutainment [

76], health care, etc. applications using different types of classifiers.

The above confirms that this database is a valuable resource for researching the affective reactions in speech communication between a child and a computer in Russian.

Nevertheless, there are some aspects of this study that need to be improved.

First, the most important challenge in the applications mentioned above is how to automatically recognize a child’s emotions with the highest possible performance. Thus, the accuracy of the speech emotion recognition must be improved. The most prominent way to solve the problem is use deep learning techniques. However, one of the significant issues in deep learning-based SER is the limited size of the datasets. Thus, we need larger datasets of children’s speech. One of the suitable solutions we suggest is to study the creation of a fully synthetic dataset using generative techniques trained on available datasets [

77]. GAN-based techniques have already shown success for similar problems and would be candidates for solving this problem as well. Moreover, we can use generative models to create noisy samples and try to design a noise-robust model for SER in real-world child communications including various gadgets for atypical children.

Secondly, other sources of information for SER should be considered, such as children’s face expression, posture, and motion.

In the future, we intend to improve the accuracy of the automatic SER by