Abstract

We first define the -CUSUM process and investigate its theoretical aspects including asymptotic behavior. By choosing different sets , we propose some tests for multiple change-point detections in a functional sample. We apply the proposed testing procedures to the real-world neurophysiological data and demonstrate how it can identify the existence of the multiple change-points and localize them.

Keywords:

p-variation; functional data; functional change-point detection; functional principal component analysis MSC:

62R10

1. Introduction

Consider a second-order stationary sequence of stochastic processes defined on a probability space , having zero mean and covariance function . For a given functional sample consider the model:

where the function is deterministic, but unobserved. Our main aim is in testing the hypothesis:

with emphasis on a case of change-point detection, which corresponds to a piecewise-constant function g with respect to the first argument.

This model covers a broad range of real-world problems such as climate change detection, image analysis, analysis of medical treatments, especially magnetic resonance images of brain activities, and speech recognition, to name a few. Besides, the change-point detection model (1) can be used for knot selection in spline smoothing as well for trend changes in functional time series analysis.

There is a huge list of references on testing for change-points or structural changes for a sequence of independent random variables/vectors. We refer to Csörgő and Horváth [1], Brodsky and Darkhovsky [2], Basseville and Nikiforov [3], and Chen and Gupta [4] for accounts of various techniques.

Within the functional data analysis literature, change-point detection has largely focused on one change-point problem. In Berkes et al. [5], a cumulative sum (CUSUM) test was proposed for independent functional data by using projections of the sample onto some principal components of covariance . Later, the problem was studied in Aue et al. [6], where its asymptotic properties were developed. This test was extended to weakly dependent functional data and epidemic changes by Aston and Kirch [7]. Aue et al. [8] proposed a fully functional method for finding a change in the mean without losing information due to dimension reduction, T. Harris, Bo Li, and J. D. Tucker [9] propose the multiple change-point isolation method for detecting multiple changes in the mean and covariance of a functional process.

The methodology we propose is based on some measures of variation of the process:

where .

Since this process is infinite-dimensional, we used the projections technique to reduce the dimension. To this aim, we assumed that is mean-squared continuous and jointly measurable and that has finite trace: . In this case, is also an -valued random element, where is a Hilbert space of Lebesgue square integrable functions on endowed with the inner product and the norm .

In the case where the number of change-points is known to be no bigger than m, our test statistics are constructed from -variation (see the definition below) of the processes , where runs through a finite set of possibly random directions in . In particular, consists of estimated principal components. If the number of change-points is unknown, we consider the p-variation of the processes and estimate the possible number of change-points.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, -sum and -CUSUM processes are defined and their asymptotic behavior is considered in a framework of the space. The results presented in this section are used to derive the asymptotic distributions of the test statistics presented in Section 3. Section 4 is devoted to simulation studies of the proposed test algorithms. Section 5 contains a case study. Finally, Section 6 is devoted to the proofs of our main theoretical results.

2. -Sum Process and Its Asymptotic

Let be the set of all probability measures on (. For any and Q-integrable function f, As usual, is a set of measurable functions on , which are square-integrable for the measure Q, and is an associated Hilbert space endowed with the inner product:

and corresponding distance , . We abbreviate to and to for Lebesgue measure . We use the norm and the distance for the elements . On the set , we use the inner product:

and the corresponding distance:

For two given sets , we consider the -sum process:

where , is a uniform probability on the interval and . A natural framework for stochastic process is the space , where . Recall for a class that is a Banach space of all uniformly bounded real-valued functions on endowed with the uniform norm:

Given a pseudometric d on , is a set of all , which are uniformly d-continuous. The set is a separable subspace of if and only if is totally bounded. The pseudometric space is totally bounded if is finite for every , where is the minimal number of open balls of d-radius , which are necessary to cover .

It is worth noting that the process is continuous when is endowed with the metric . Indeed,

since for every If both sets and are totally bounded, then the process is uniformly continuous so that takes values in the subspace .

Next, we specify the set . To this aim, we recall some definitions. For a function , a positive number , and an integer , the -variation of f on the interval is

where the supremum is taken over all partitions of the interval . We abbreviate . If , then we say that f has finite p-variation and is the set of all such functions. The set , , is a (non-separable) Banach space with the norm:

The embedding is continuous and

For more information on the space , we refer to [10].

The limiting zero mean Gaussian process is defined via covariance:

where is the covariance operator corresponding to the kernel . The function is positive definite:

for all , , and . Indeed, if we denote by the isonormal Gaussian process on the Hilbert space , we see that

hence,

and (3) follows. This justifies the existence of the process .

Throughout, we shall exploit the following.

Assumption 1.

Random processes are i.i.d. mean square continuous, jointly measurable, with mean zero and covariance γ such that .

For the model (1), we consider null hypothesis and two possible alternatives:

and

In both alternatives, the function is responsible for the configuration of a drift within the sample, whereas the function estimates a magnitude of the drift.

Our main theoretical results are Theorems 1 and 3, which are proven in Section 6.

Theorem 1.

Let the random processes be defined by , where satisfy Assumption 1. Assume that, for some , the set is bounded and the set satisfies

Then, there exists a version of a Gaussian process on such that its restriction on , is continuous and the following hold:

- (1a)

- Under :

- (1b)

- Under ,where

If , then the alternative corresponds to the presence of a signal in a noise. In this case, Therefore, the use of this theorem for testing a signal in a noise is meaningful provided .

As a corollary, Theorem 1 combined with the continuous mapping theorem gives the following result.

Theorem 2.

Assume that conditions of Theorem 1 are satisfied. Then, the following hold:

- (2a)

- Under

- (2b)

- Under ,

- (2c)

- Under ,

Proof.

Since both (2a) and (2b) are by-products of Theorem 1 and continuous mappings, we need to prove only (2c). First, we observe that

by (2a). Consider

We have

By the Hölder inequality,

Since , we deduce

Hence,

and this completes the proof of (2c). □

Next, we consider -sum process defined by

where . Its limiting zero mean Gaussian process is defined via covariance:

The existence of Gaussian process can be justified as that of above. Just notice that

where .

Theorem 3.

Assume that the conditions of Theorem 1 are satisfied. Then, there exists a version of the Gaussian process on such that its restriction on , is continuous and the following hold:

- (3a)

- Under ,

- (3b)

- Under alternative ,where

We see that the limit distribution of the -sum process separates the null and alternative hypothesis provided . As a corollary, Theorem 3 combined with the continuous mapping theorem gives the following results.

Theorem 4.

Assume that the conditions of Theorem 1 are satisfied. Then, the following hold:

- (4a)

- Under ,

- (4b)

- Under ,

- (4c)

- Under ,

Proof.

Both (4a) and (4b) are by-products of Theorem 3 and continuous mappings, whereas the proof of (4c) follows the lines of the proof of Theorem 2 (2c). □

3. Test Statistics

Several useful test statistics can be obtained from the -sum process by considering concrete examples of sets and .

Throughout this section, we assume that the sample follows the model (1) and satisfies Assumption 1.

By , we denote the covariance operator of Y: . Recall

According to Mercer’s theorem, the covariance has then the following singular-value decomposition:

where are all the decreasingly ordered positive eigenvalues of and are the associated eigenfunctions of such that

and m is the smallest integer such that, when , . If , then all the eigenvalues are positive, and in this case, . Note that Besides, we shall assume the following.

Assumption 2.

The eigenvalues satisfy, for some

In statistical analysis, the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of Γ are replaced by their estimated versions. Noting that, for each k,

one estimates Γ by

where We denote the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of by and , respectively. In order to ensure that may be viewed as an estimator of rather than of , we will in the following assume that the signs are such that . Note that

and

The use of the estimated eigenfunctions and eigenvalues in the test statistics is justified by the following result. For a Hilbert–Schmidt operator T on , we denote by its Hilbert–Schmidt norm.

Lemma 1.

Assume that Assumption 1 holds. Then, under ,

Proof.

First, we observe that

where

It is well known that as . By the moment inequality for sums of independent random variables, we deduce

for both . This yields . Next, we have

as due to assumption . This completes the proof. □

Lemma 2.

Assume that Assumptions 1 and 2 for some finite d hold and Then, under , as well as under :

for each , where .

Proof.

If the null hypothesis is satisfied, then and the asymptotic results for the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of are well known (see, e.g., [11]). Under alternative , the results follow from Lemma 1 and Lemmas 2.2 and 2.3 in [11]. □

Next, we consider separately the test statistics for at most one, at most m, and for an unknown number of change-points.

3.1. Testing at Most One Change-Point

Define for ,

This statistic is designed for at most one change-point alternative. Its limiting distribution is established in the following theorem.

Theorem 5.

Let random functional sample be defined by where satisfies Assumptions 1 and 2. Then,

- (a)

- Under , it holds thatwhere are independent standard Brownian bridge processes;

- (b)

- Under , it holds thatwhere

- (c)

- Under , it holds that

Proof.

Consider the sets

Observing that

and is a bounded set in , we complete the proof by applying Theorem 3. □

Based on this result, we construct the testing procedure in a classical way. Choose for a given , such that

According to Theorem 5, the test:

will have asymptotic level . Under the alternative , we have

when

Hence, if and

as , then the test (20) is asymptotically consistent.

Let us note that, due to the independence of Brownian bridges , we have

This yields

Hence, is the -quantile of the distribution of . This observation simplifies the calculations of critical values .

In particular, if there is such that then we have one change-point model:

In this case,

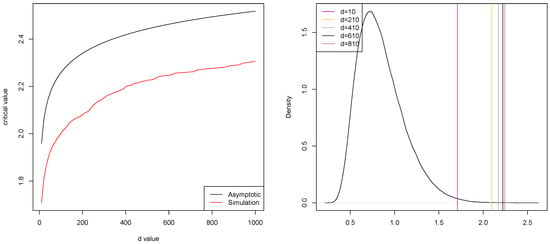

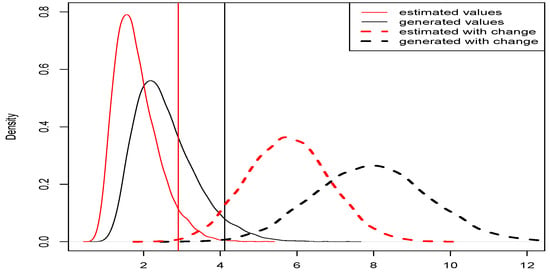

Figure 1 below shows generated density functions of and for , where for a fixed k.

Figure 1.

Density functions.

Let us observe that test statistic tends to infinity when . On the other hand, with larger d, the approximation of by series is better and leads to better testing power. The following result establishes the asymptotic distribution of as .

Theorem 6.

Let random functional sample be defined by where satisfies Assumption 1. Then, under ,

where

Proof.

By Theorem 5, the proof reduces to

It is known that

Since Brownian bridges are independent, we have

and

This proves (24). □

The dependence on d of critical values of the tests (20) and (25) is shown in Figure 2. A comparison was made for asymptotic level . From Figure 2, we see that the critical values in (25) are smaller than those in (20). This means that the error of the first kind is more likely with the test (25), rather than with (36). This is confirmed by simulations.

If the eigenfunctions are unknown, we use the statistics:

Theorem 7.

Let random functional sample be defined by , where satisfies Assumptions 1 and 2. Then:

- (a)

- Under ,where are independent standard Brownian bridge processes;

- (b)

- Under , if , it holds thatwhere .

- (c)

- Under , if , it holds that

Proof.

The result follows from Theorem 5 if we show that

On the set and for such that , simple algebra gives where

and

by the law of large numbers. Lemma 2 concludes the proof. □

Test (20) now becomes

and has asymptotic level by Theorem 7.

3.2. Testing at Most m Change-Points

For , let be a set of all partitions of the set such that . Next, consider for fixed integers d, and real ,

The statistics are designed for testing at most m change-points in a sample.

Theorem 8.

Let the random sample be as in Theorem 1. Then:

- (a)

- Under ,where are independent standard Brownian bridges.

- (b)

- Under ,where is as defined in Theorem 2.

- (c)

- Under ,

Proof.

For and , set

It is easy to check that . Since

we have

and the results follow from Theorem 2. □

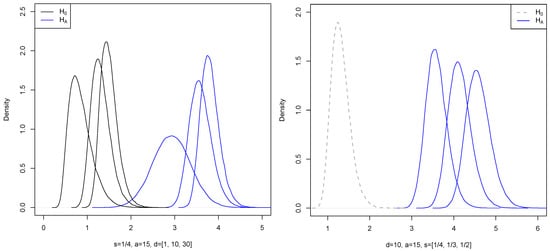

In particular, if there is such that then (1) corresponds to the so-called changed segment model. In this case, we have . Figure 3) shows the generated density functions of and for different values of , , and . The numbers were sampled from the uniform distribution on .

Figure 3.

Functions and density functions.

With the estimated eigenvalues and eigenfunctions, we define

Theorem 9.

Let the functional sample be defined by where satisfies Assumptions 1 and 2. Then:

- (a)

- Under ,where are independent standard Brownian bridges.

- (b)

- Under ,where is as defined in Theorem 2.

- (c)

- Under ,

Proof.

This goes along the lines of the proof of Theorem 7. □

According to Theorems 8 and 9, the tests:

respectively, will have asymptotic level , if is such that

3.3. Testing Unknown Number of Change-Points

Next, consider for fixed integers d as above and real ,

The statistics are designed for testing an unknown number of change-points in a sample.

Theorem 10.

Let random sample be as in Theorem 1. Then:

- (a)

- Under ,where are independent standard Brownian bridges.

- (b)

- Underwhere is as defined in Theorem 1.

- (c)

- Under ,

Proof.

For , set

It is easy to check that . Since

we have

and both statements (a) and (b) follow from Theorem 1. □

With the estimated eigenvalues and eigenfunctions, we define:

Theorem 11.

Let random sample be as in Theorem 1. Then:

- (a)

- Under ,where are independent standard Brownian bridges.

- (b)

- Underwhere is as defined in Theorem 1.

- (c)

- Under ,

Proof.

This goes along the lines of the proof of Theorem 7. □

According to Theorems 10 and 11, the tests:

respectively, will have asymptotic level , if is such that

The quantiles of distribution function of were estimated in [12].

4. Simulation Results

We examined the above-defined test statistics in a Monte Carlo simulation study. In the first subsection, we describe the simulated data under consideration. The statistical power analysis of the tests (36) and (32) is presented in Section 4.2.

4.1. Data

We used the following three scenarios:

- (S1)

- Let be i.i.d. symmetrized Pareto random variables with index p (we used ). Setwhere . Under the null hypothesis, we take .Under the alternative, we considerwhere the function defines the change-points’ configuration and the coefficients are subject to choice.

- (S2)

- We start with discrete observations by taking , where the random sample () is generated as in scenario (S1). Discrete observations are converted to the functional data by using B-spline bases.

- (S3)

- Discrete observations are generated by takingso that can be interpreted as the observation of a standard Wiener process at . From , the function is obtained using the B-spline smoothing technique. During the simulation, we used and B-spline functions, thus obtaining functions . Then, we define for ,and consider different configurations of change-points and ,

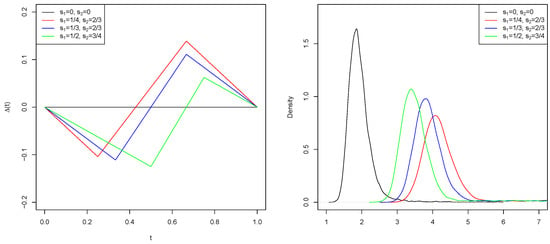

We mainly concentrated on two possible change-point alternatives. The first is obtained with and corresponds to one change-point alternative. Another is for the epidemic-type alternative, for which we take .

Scenario (S1) is used as an optimal case situation where the actual eigenvalues and eigenfunctions are known. In this case, we are not required to approximate discrete functions, thus avoiding any data loss or measurement errors. The second scenario continues with the same random functional sample, but goes through extra steps such us taking function values at discrete data points and reconstructing the random functional sample on a different set of basis functions. The aim of this exercise is to measure the impact when some information could be lost due to measurements taken at discrete points and smoothing. The simulation results show that, even after the reconstruction of the random functional sample, the performance of the test does not suffer too much.

Our simulation starts with the generation process of the random functional sample as described in the first scenario with .

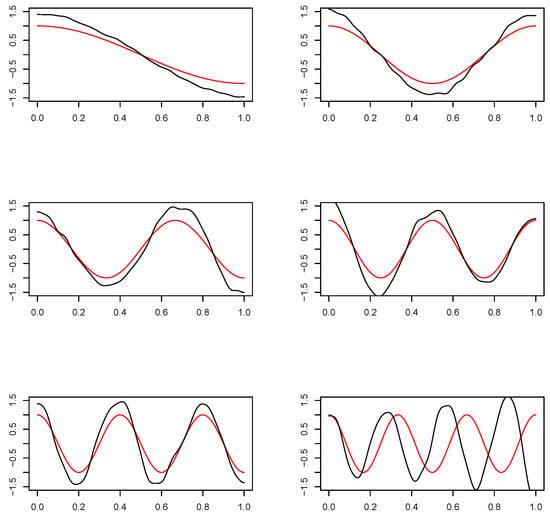

First of all, we can compare the true eigenfunctions of covariance operator with the eigenfunctions of estimated operator (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

True basis functions (red) and “reconstructed” basis functions (black) using fPCA method.

We see that the estimated harmonics has almost the same shape; only every second, the estimated eigenfunctions are phase shifted.

Next, for both scenarios (S1) and (S2), the density functions of the test statistic (17) were estimated using Monte Carlo with 10,000 repetitions (see Figure 5). It shows four density plots: the red density functions of are calculated using the true eigenfunctions and eigenvalues, while the black curves show the density of (26) using the estimated eigenfunctions and eigenvalues. The left side density plots were estimated from the samples under the null hypothesis, while the plots on the right side show the density of and with the sample:

with added drift .

Figure 5.

Density plots of the test statistic and .

Since functional Principal Component Analysis (fPCA) represents a functional data sample in the most parsimonious way, we can see that the density of the test statistics in scenario (S2) is more on the left side and more concise. Critical values with of the statistics and were also calculated and are shown in Figure 5.

4.2. Statistical Power Analysis

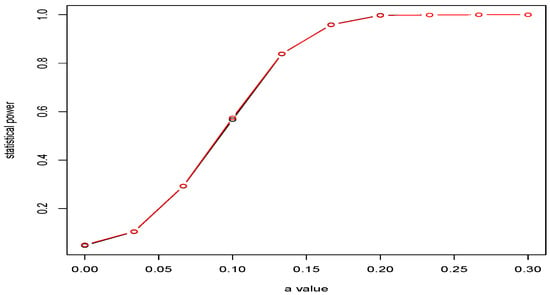

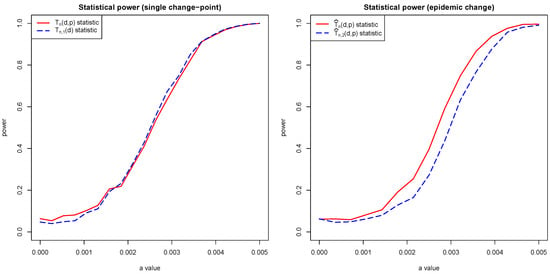

First, we compared the statistical power of the test (20) with statistic of the scenario (S1) and scenario (S2) with statistic . To this aim, we used sample defined in (38), where , which is in the middle of the sample. We started with the no drift (corresponding to the null hypothesis) and increasing the drift amount a by up to the point when . At each a value, we repeated the simulation 1000 times. This gives a good indication of the statistical power with the amount of the added drift. The statistical power is illustrated in Figure 6. Based on the simulation results, we can see that, even if the random functional sample is approximated from the discrete data points, it still holds the same statistical power and the performance does not suffer from the information loss due to smoothing and fPCA. These are important results, because, normally, in observed real-world data, the true functions are unknown and have to be approximated, which almost always introduces measurement errors.

Figure 6.

The comparison of the statistical power of scenario (S1) and (S2).

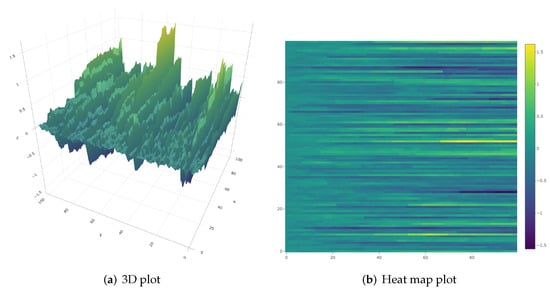

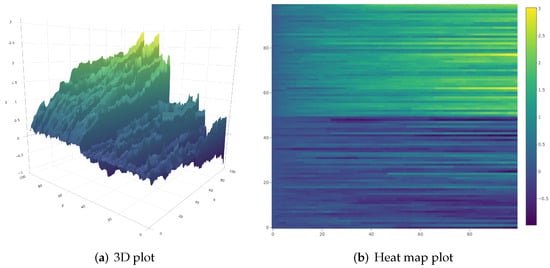

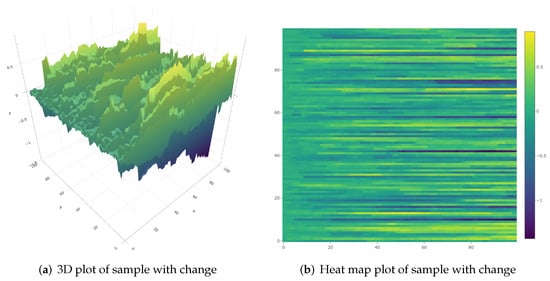

Next, we focus on the power tests (36) and (32) used directly on the functional data sets simulated in scenario (S3). Figure 7 and Figure 8 present the clear opposites of the functional data sets with respect to the change-point. The changes can be easily observed. However, especially working with functional data sets, the changes may not be that obvious. As an example, Figure 9 illustrates another functional data set with the change-point, where the presence of the change-point is not visible, but Monte Carlo experiments show that, with the same magnitude of change, for almost 80% of the cases, was correctly rejected.

Figure 7.

Functional data set .

Figure 8.

Functional sample with one change-point.

Figure 9.

Sample with introduced drift of magnitude after the change-point.

The density of the limiting distribution and asymptotic critical values were estimated using the Monte Carlo technique by simulating a Brownian bridge with 1000 points and running 100,000 replications.

In the power studies, we tested two variants of the random functional samples, one with a single change-point in the middle of the functional sample and the second with the two change-points forming epidemic change. In the first case, the functional sample is constructed from random functions where 500 curves are changed in order to violate the null hypothesis. The model that violates the null hypothesis is defined as , , and the parameter a is used to control the magnitude of the drift after the change-point. In the second case, during each iteration, random functions are generated, where 500 curves in the middle were modified by taking . During each repetition, twostatistics are calculated: (35) and (26) in the single change-point simulation. For the epidemic change simulation (31), statistic is calculated. We set the p-variation p parameter to 3. We also tested with different p-values, but this did not have any impact on the overall performance.

Figure 10 presents the results of the statistical power simulation. From the results, we can see that epidemic change has weaker statistical power. On the other hand, when restricting the partition count, we observed one benefit, that the locations of the partitions in many cases match or are very close to the actual locations of the change-point.

Figure 10.

Power curves.

5. Application to Brain Activity Data

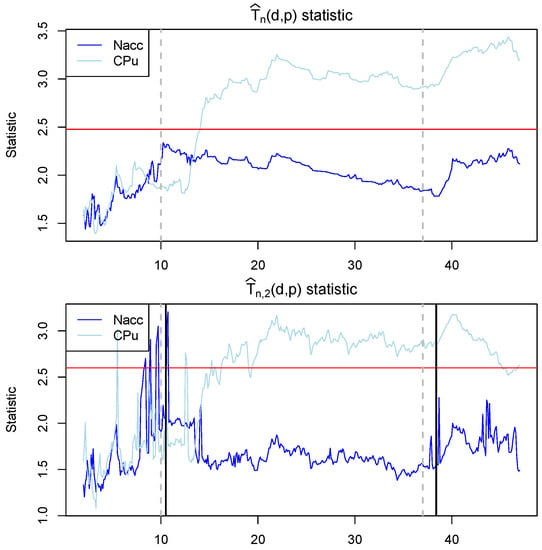

The findings of real data analysis to show the performance of the proposed test are demonstrated in this section. The data were collected during a long-term study on voluntary alcohol- consuming rats following chronic alcohol experience. The data consist of two sets: neurophysiological activity from the two brain centers (the dorsal and ventral striatum) and data from the lickometer device. The lickometer devices were used to monitor the drinking bouts. During the single trial, two locations of the brain were monitored for each rat. Rats were given two drinking bouts, one with alcohol and the other with water. Any time, they were able to freely choose what to drink. Electrodes were attached to the brains, and neurophysiological data were sampled at 1kHz intervals. It was not the goal of this study to confirm nor reject the findings, but to show the advantages of the functional approach for change-point detection. For this reason, the data are well suited to illustrate the behavior of the test in real-world settings.

In our analysis, we took the first alcohol drinking event, which lasted around 27 s. We also included 10 s before the drinking event and 10 s after the event. The total time was 47 s long. The time series was broken down into processes of 100 ms. Each process had 100 data points.

All the processes were smoothed to the functions using 50 B-spline basis functions. The overall functional sample contained 470 functions . The functional sample was separated into sub-samples , . For each sub-sample , two statistics were calculated ( (35) and (31), ).

The results are visualized in Figure 11. We can see that tests with statistics and strongly rejected the null hypothesis at around 2 s and onward after the rat started to consume the alcohol, which suggests that the changes in the brain activity can be observed. However, the changes appear to happen only for the CPu brain region. Interestingly, the statistic has much larger volatility compared to the unrestricted in the Nacc brain region before the drinking event and lower volatility just after the drinking event started. However, it is not fully clear if this is the expected behavior or a Type I error.

Figure 11.

Statistics of the first alcohol drinking event, which lasted about 27 s. Ten seconds before and 10 s after were also included. The red horizontal line indicates the critical value with 0.95. Vertical gray dashed lines mark the beginning and the end of the drinking time. The black solid vertical lines mark the locations of the change-points detected using the restricted p-variation method. Blue and light blue colors represent different brain regions.

Finally, the locations of the restricted () p-variation partition points nearly matched the beginning and the end of the drinking period. In Figure 11, the gray vertical dashed lines indicate the actual beginning and the actual end of the drinking period measured by the lickometer and the black vertical lines indicate the location of the partitions calculated from the functional sample . The first partition is located at 10.5 s and the second partition point at 38.4 s, which aligns well with the data collected from the lickometer.

The test with a restricted partition count showed weaker statistical power, but it did help determine the location of the change-points.

6. Proof of Theorems 1 and 3

The following theorem is a version of Theorem 2.11.1 in [13] adapted to the case of continuous processes.

Theorem 12.

Assume that are independent continuous stochastic processes indexed by a totally bounded semi-metric space such that

where

Then, the sequence is asymptotically d-equicontinuous, that is, for every ,

Furthermore, converges in law in provided that covariances converge pointwise on .

Proof of Theorem 1 (1a).

Without loss of generality, we assumed that for all and for all . To prove , we applied Theorem 12 for , , and , , where, under , . Let us check first the conditions (39)–(41). We have

Hence, (39) easily follows from Since

and are identically distributed, we have

Summing this estimate and noting that for any ,

by the Hölder inequality, we find

if This estimate yields (40). To check (41), we have

where

Hence,

and the condition (41) is satisfied, provided that

and

hold. Set

It is known (see, e.g., [14]) that . Hence, as . By the condition (4), as . Changing the integration variables gives and .

Set . By the strong law of large numbers, . Choosing , we have, for any ,

as . Similarly, we prove .

Next, we have to check the pointwise convergence of the covariances of . Since are independent, we have

We shall prove that

Set . Evidently, , and we have to check

We have

where

Observing that

we have

This yields

To complete the proof of , note that the existence of the continuous modification of Gaussian process follows by Dudley [15], since the entropy condition is satisfied. □

Lemma 3.

It holds that

Proof.

We have

For every ,

Hence,

and this completes the proof. □

Proof of Theorem 1 (1b).

Under ,

Hence,

where

and

We have by (1a)

To complete the proof, we have to check

and

To this aim, we involve lemma 3. We have

where

By Lemma 3 applied to the function , we have uniformly over . Consider . We have, as in the proof of Lemma 3,

Hence, uniformly over . The convergence (45) follows by observing that

This proves (45) and completes the proof of (1b). □

Proof of Theorem 3 (3a).

Consider the map . The continuity of T is easy to check. Observing that , the convergence (9) is a corollary of Theorem 1 and a continuous mapping theorem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.; Methodology, A.R.; Software, T.D.; Supervision, A.R.; Formal analysis, T.D. and A.R.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.R., T.D.; Investigation, T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Csörgő, M.; Horváth, L. Limit Theorems in Change-Point Analysis; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky, B.E.; Darkhovsky, B.S. Non Parametric Methods in Change Point Problems; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Basseville, M.; Nikiforov, N. The Detection of Abrupt Changes—Theory and Applications; Information and System Sciences Series; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Gupta, A.K. Parametric Statistical Change Point Analysis; Birkhauser Boston, Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Berkes, I.; Gabrys, R.; Horváth, L.; Kokoszka, P. Detecting changes in the mean of functional observations. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Stat. Methodol.) 2009, 71, 927–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aue, A.; Gabrys, R.; Horváth, L.; Kokoszka, P. Estimation of a change-point in the mean function of functional data. J. Multivar. Anal. 2009, 100, 2254–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aston, J.A.; Kirch, C. Detecting and estimating changes in dependent functional data. J. Multivar. Anal. 2012, 109, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aue, A.; Rice, G.; Sönmez, O. Detecting and dating structural breaks in functional data without dimension reduction. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Stat. Methodol.) 2018, 80, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harris, T.; Li, B.; Tucker, J.D. Scalable Multiple Changepoint Detection for Functional Data Sequences. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2008.01889v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, R.M.; Norvaiša, R. Concrete Functional Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Horváth, L.; Kokoszka, P. Inference for Functional Data with Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Danielius, T.; Račkauskas, A. p-Variation of CUSUM process and testing change in the mean. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- der Vaart, A.W.V.; Wellner, J.A. Weak Convergence and Empirical Processes with Applications to Statistics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Norvaiša, R.; Račkauskas, A. Convergence in law of partial sum processes in p-variation norm. Lith. Math. J. 2008, 48, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, R.M. Sample functions of the gaussian process. Ann. Probab. 1973, 1, 66–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).