PTMs_Closed_Search: Multiple Post-Translational Modification Closed Search Using Reduced Search Space and Transferred FDR

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

2.2. Access and Implementation

2.3. Input Files

2.4. “Ptms_Closed_Search” Pipeline

2.4.1. Preprocessing (Module I)

- A list of proteins is generated based on the results of a standard MS/MS search using the IdentiPy [24] search engine and FASTA file for an organism downloaded from UniProtKB. The standard search parameters of IdentiPy were used as the default with the “auto-tuning” of search parameters enabled. Also, parameters for standard MS/MS search were specified according to the dataset description.

- In accordance with the list of identified proteins (Step 1), the UniProtKB and dbPTM query databases are automatically parsed to annotate a set of PTMs for each protein (Figure S1).

- The procedure generates a set of FASTA files for each PTM annotated in Step 2. Then, 5000 forward and 5000 reverse random protein sequences are appended to each generated FASTA file. The configuration parameter files for each search are prepared as follows: individual PTMs are designated as variable, and the name of the generated database specified.

2.4.2. Multiple Search (Module II)

- 4.

- A sequential multiple PTM search was performed using IdentiPy with the “auto-tuning” parameter switched off. The parameters of “precursor mass tolerance” and “fragment mass tolerance” are set based on the optimized value of the precursor mass distribution found in Step 1.

2.4.3. Postprocessing (Module III)

- 5.

- The FDR statistic is calculated to evaluate the threshold based on the hyperscore for each modification-specific search at the peptide spectrum match (PSM) using the “target–decoy” method.

- 6.

- The results of the individual PTM searches were filtered based on their calculated threshold at 1% of FDR. These individual searches are then merged into a combined PTM result for the analysis.

- 7.

- The results of the PTM search are visualized by automatically generating plots in .png format and summary tables in .csv format. These plots and tables display protein coverage, the number of modified peptides and proteins in the sample, and the positions of modifications in protein sequences in .html format.

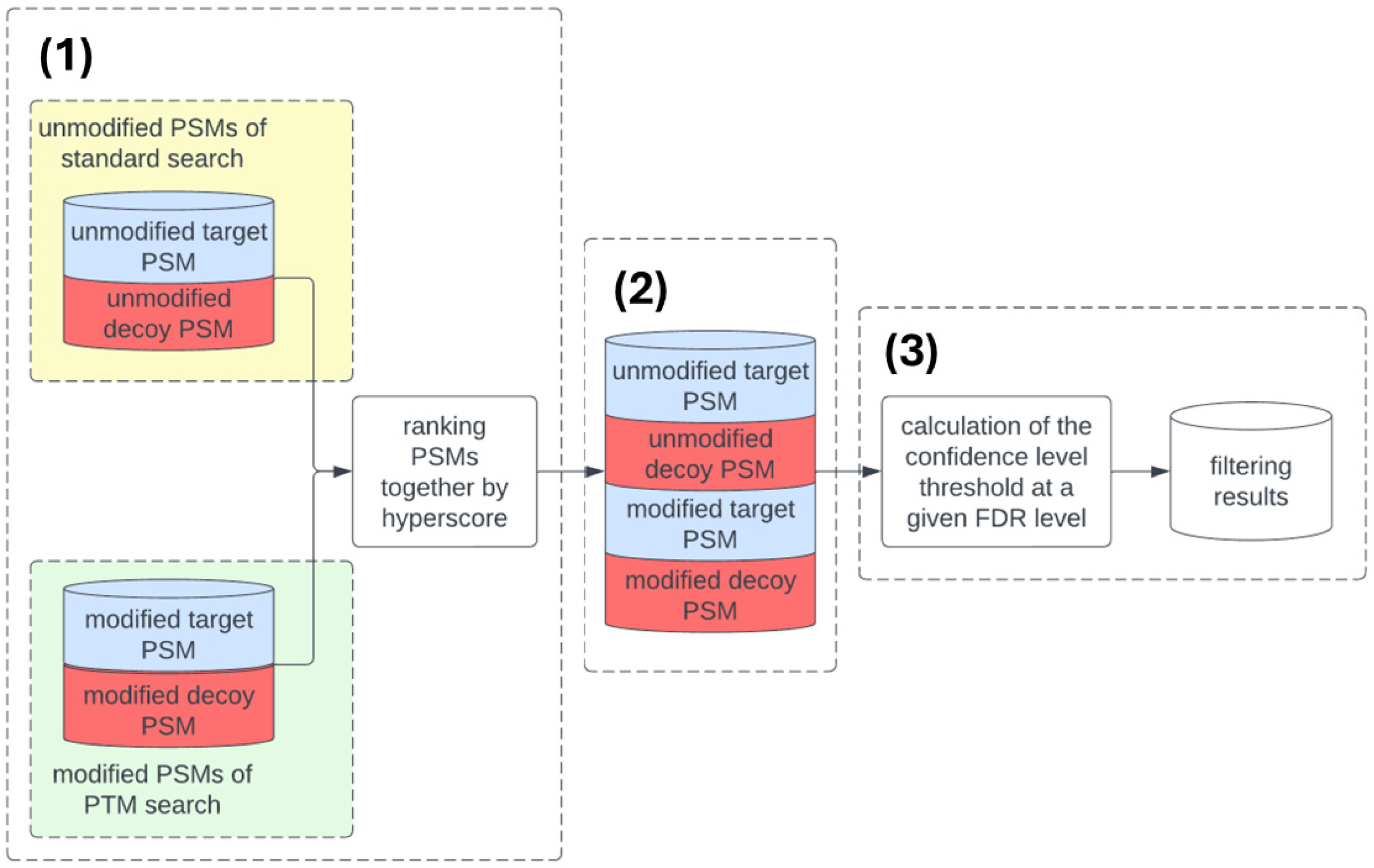

2.5. Data Filtering Pipeline

- Unmodified PSMs from the standard search and PSMs with PTMs from multiple searches are merged. All PSMs, both modified and unmodified, are sorted in ascending order by their calculated hyperscore values. For each PSM, a rank is assigned. The first PSM is assigned rank 1, and the last PSM on the list is assigned a rank equal to the total number of identified PSMs.

- To calculate the PTM-specific FDR, the merged dataset is split into four subsets of unmodified and modified PSMs, as well as target and decoy PSMs.

- The confidence threshold value at a given FDR level is calculated using the transferred FDR method [11]. This threshold is then used to filter the results of searching for PSMs with PTM.

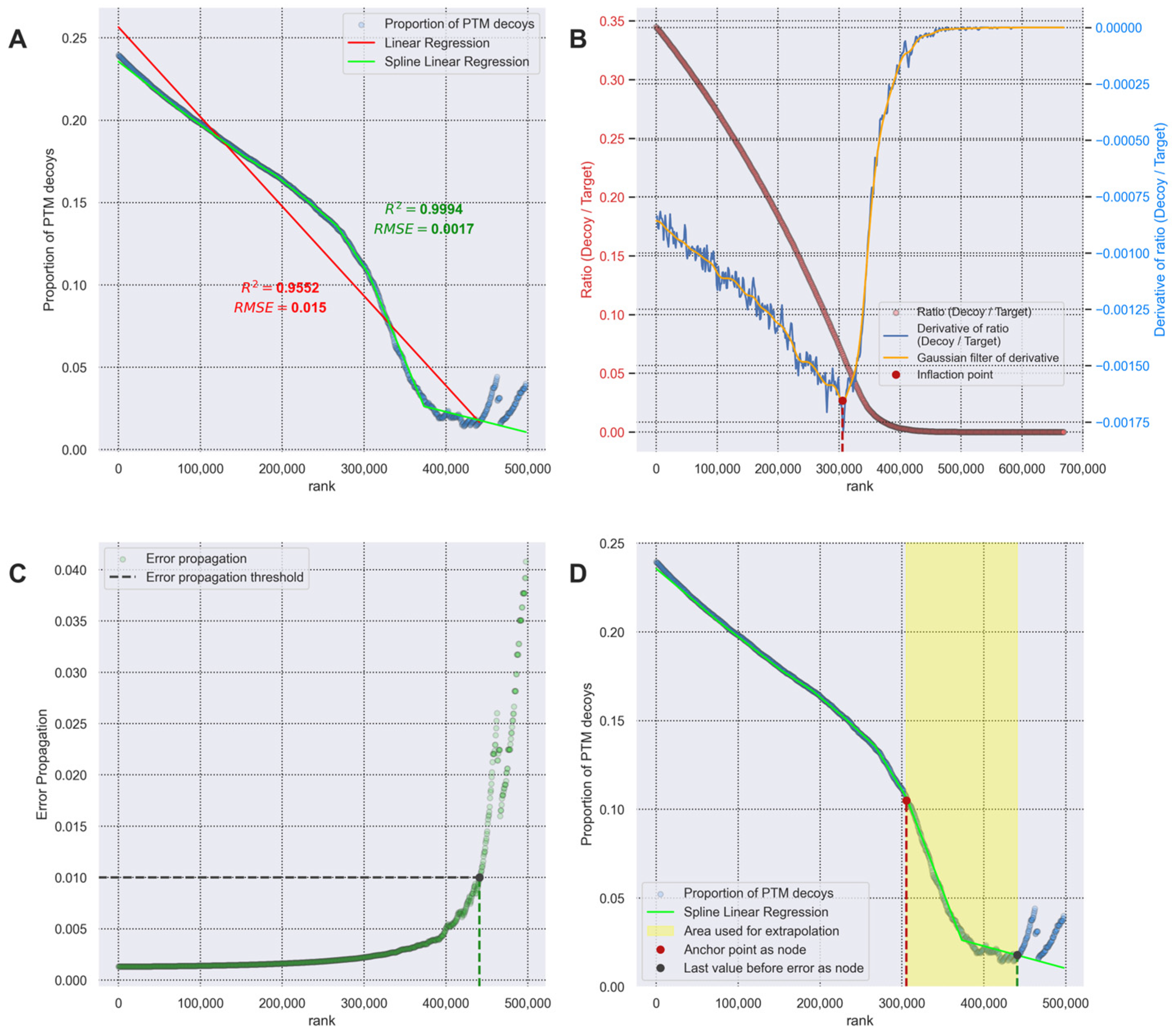

2.5.1. Transferred FDR Calculation

2.5.2. Error Propagation Calculation for Data Filtering

2.6. Parameters of MSFragger Search

3. Results

3.1. Standard Search

3.2. Search Space Optimization

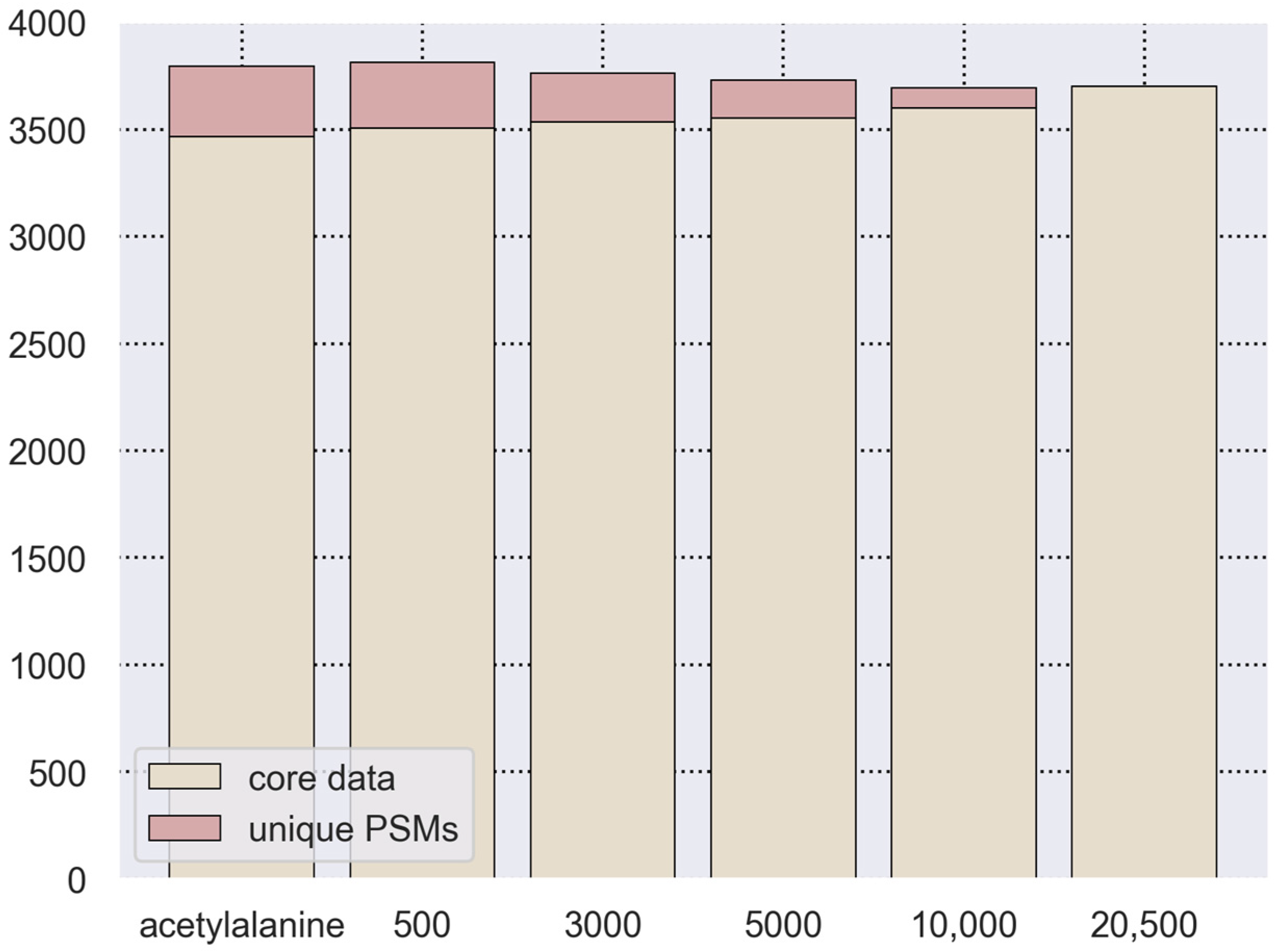

3.3. Transferred FDR and Error Propagation Data Filtering

3.4. Testing the Algorithm on HEK293 LC-MS/MS Data

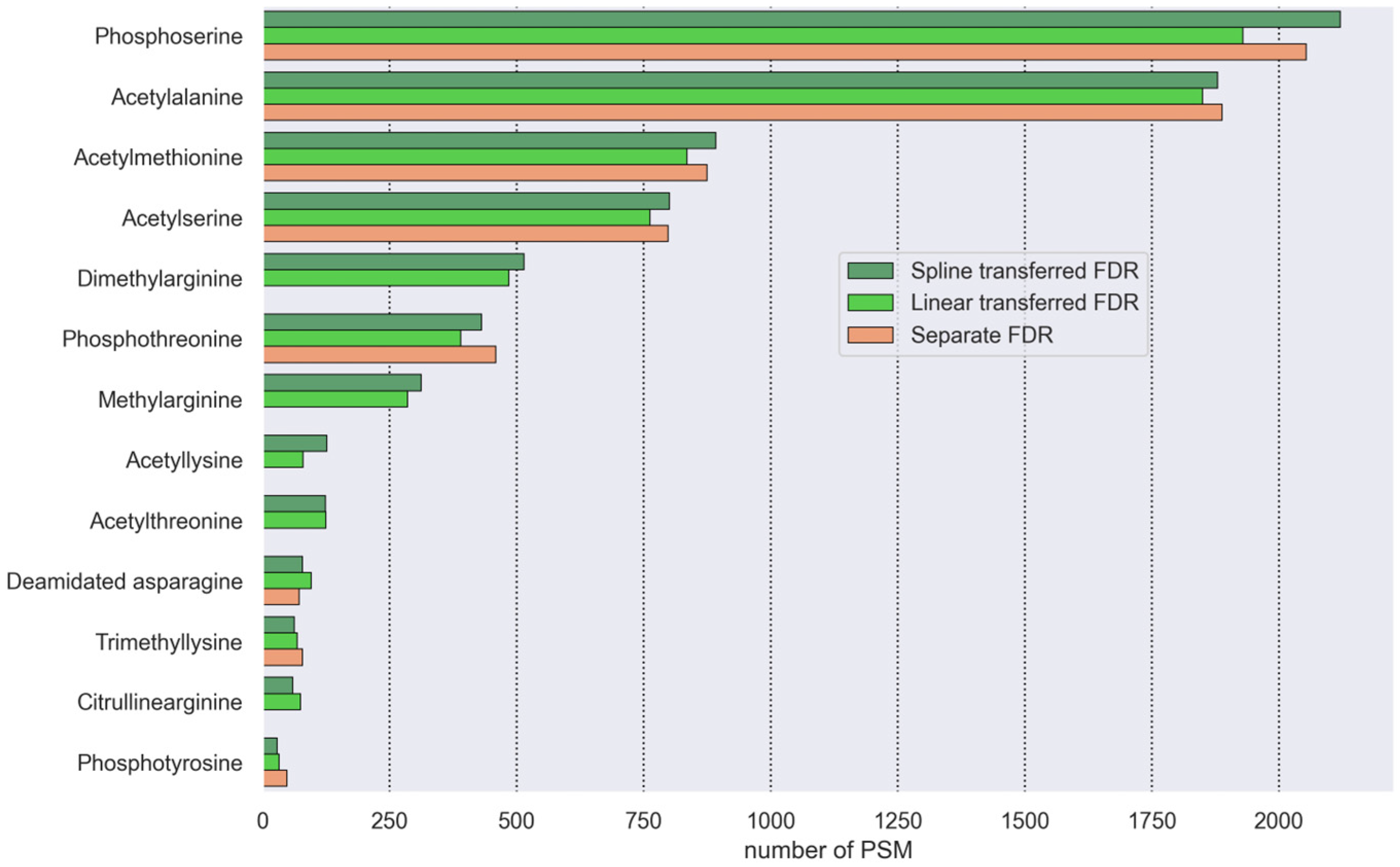

3.4.1. Transferred FDR and Separate FDR Comparison

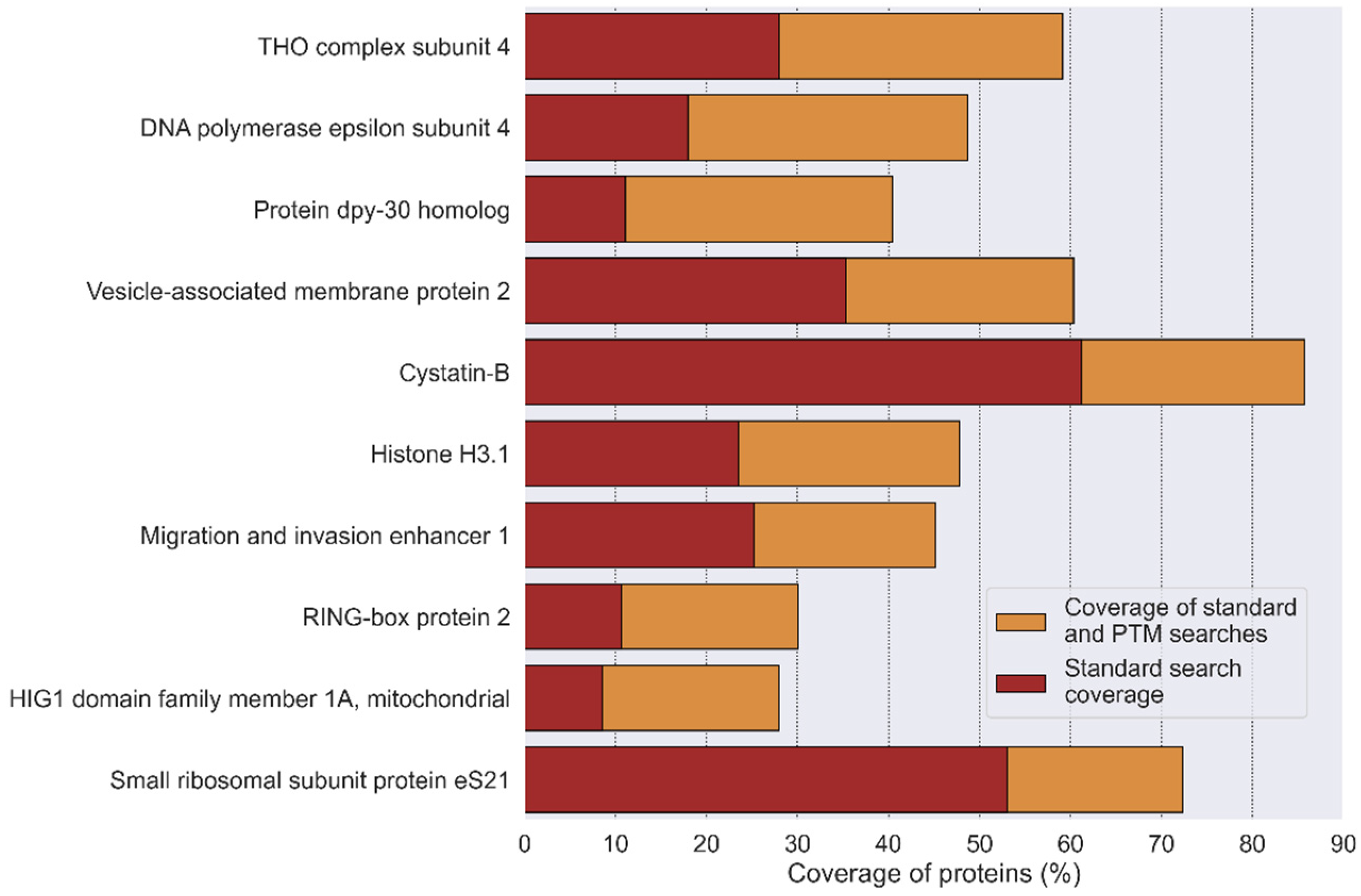

3.4.2. Coverage Increase by Modified Peptide Search

3.4.3. PTM Site Localization

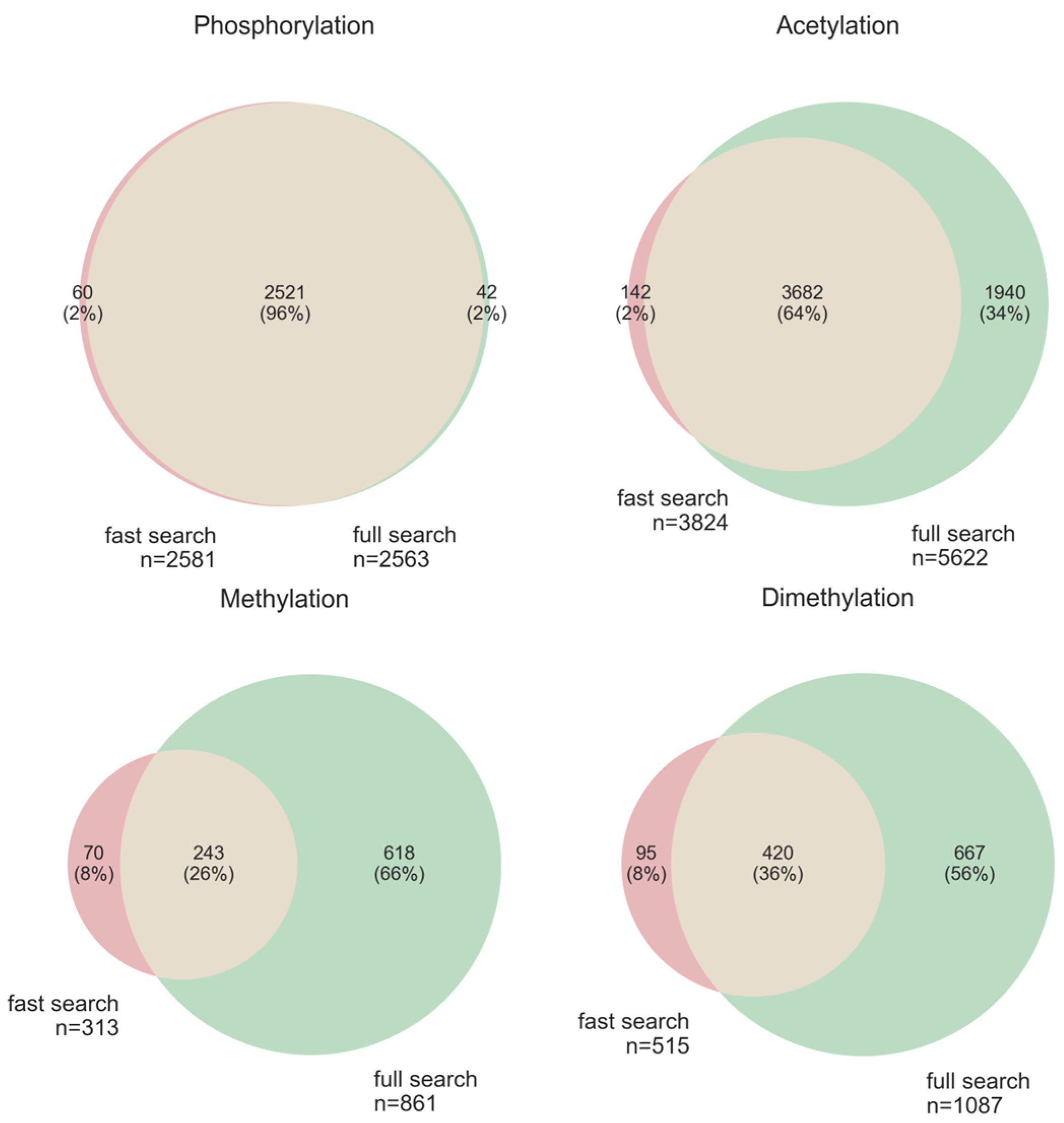

3.5. Comparison of “Ptms_Closed_Search” on Truncated and Full Databases

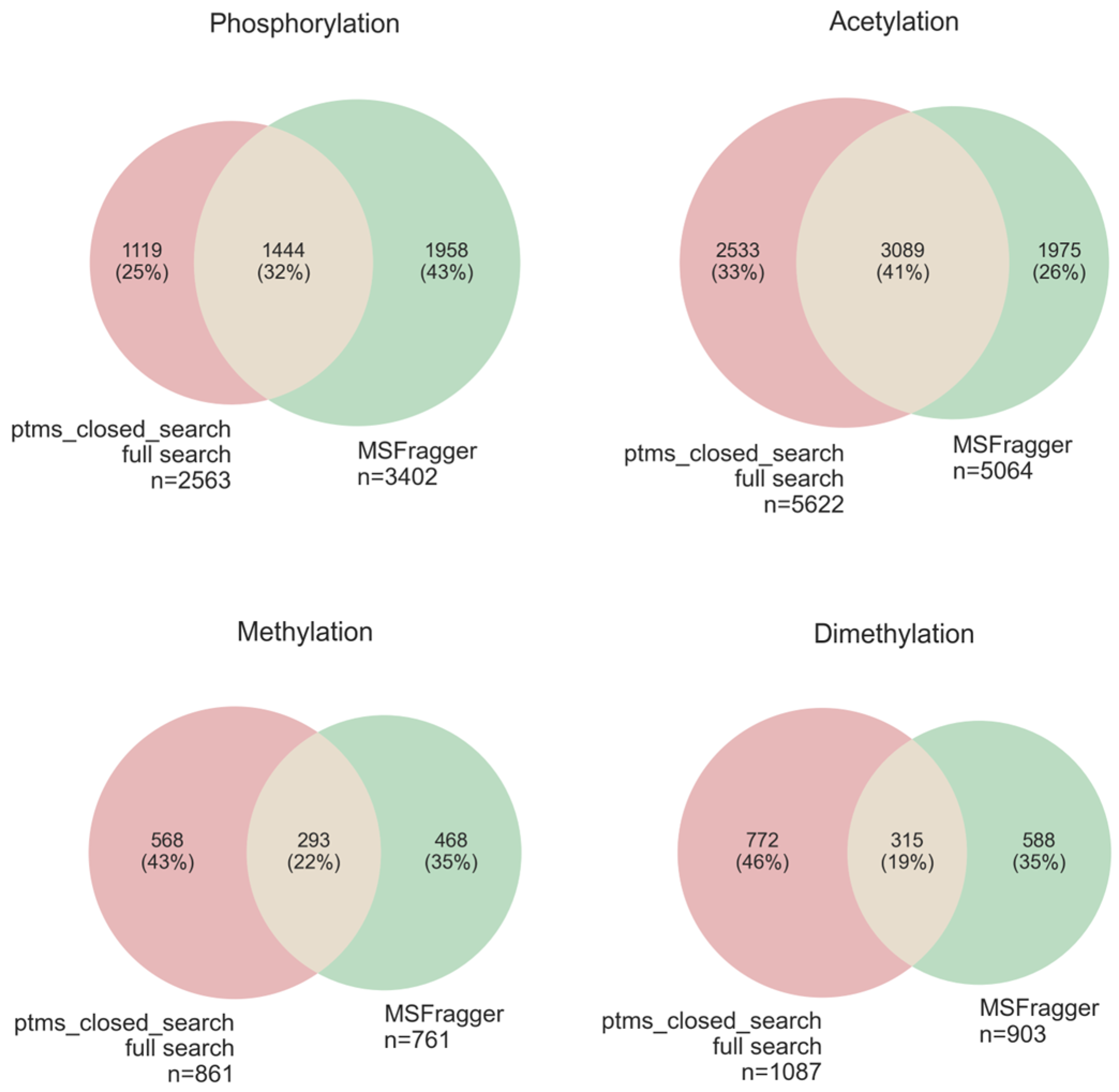

3.5.1. Comparison of Closed Search (“ptms_closed_search”) to Open Modification Search (“MSFragger”)

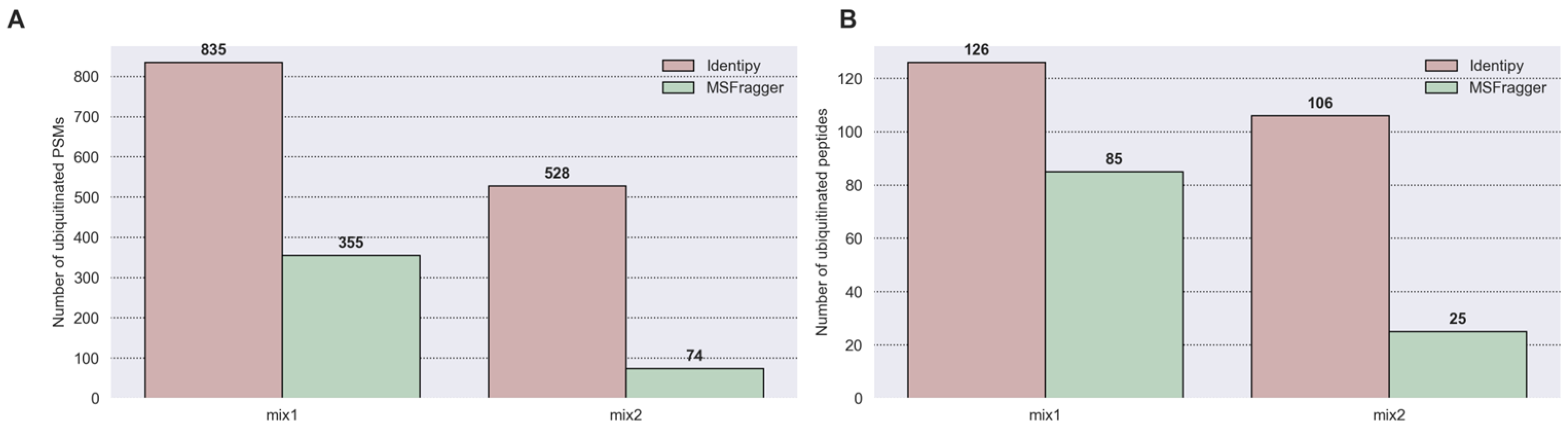

3.5.2. Sensitivity Comparison of CS (“Identipy”) and OMS (“MSFragger”) on 20 Spike-In Ubiquitinated Proteins

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PTM | Post-translational modification |

| OMS | Open modification search |

| CS | Closed search |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| PSM | Peptide spectrum match |

References

- Hong, X.; Li, N.; Lv, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.-F. PTMint Database of Experimentally Verified PTM Regulation on Protein–Protein Interaction. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btac823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorina, A.A.; Los, D.A.; Klychnikov, O.I. Serine-Threonine Protein Kinases of Cyanobacteria. Biochemistry 2025, 90, S287–S311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keenan, E.K.; Zachman, D.K.; Hirschey, M.D. Discovering the Landscape of Protein Modifications. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 1868–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulze, S.; Igiraneza, A.B.; Kösters, M.; Leufken, J.; Leidel, S.A.; Garcia, B.A.; Fufezan, C.; Pohlschroder, M. Enhancing Open Modification Searches via a Combined Approach Facilitated by Ursgal. J. Proteome Res. 2021, 20, 1986–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrné, E.; Müller, M.; Lisacek, F. Unrestricted Identification of Modified Proteins Using MS/MS. Proteomics 2010, 10, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.-E.; Mittler, G.; Mann, M. Identifying and Quantifying in Vivo Methylation Sites by Heavy Methyl SILAC. Nat. Methods 2004, 1, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Käll, L.; Storey, J.D.; MacCoss, M.J.; Noble, W.S. Assigning Significance to Peptides Identified by Tandem Mass Spectrometry Using Decoy Databases. J. Proteome Res. 2008, 7, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, M.V.; Lobas, A.A.; Karpov, D.S.; Moshkovskii, S.A.; Gorshkov, M.V. Comparison of False Discovery Rate Control Strategies for Variant Peptide Identifications in Shotgun Proteogenomics. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16, 1936–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.; Cha, S.W.; Na, S.; Guest, C.; Liu, T.; Smith, R.D.; Rodland, K.D.; Payne, S.; Bafna, V. Proteogenomic Strategies for Identification of Aberrant Cancer Peptides Using Large-scale Next-generation Sequencing Data. Proteomics 2014, 14, 2719–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kertesz-Farkas, A.; Keich, U.; Noble, W.S. Tandem Mass Spectrum Identification via Cascaded Search. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 3027–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Qian, X. Transferred Subgroup False Discovery Rate for Rare Post-Translational Modifications Detected by Mass Spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2014, 13, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chick, J.M.; Kolippakkam, D.; Nusinow, D.P.; Zhai, B.; Rad, R.; Huttlin, E.L.; Gygi, S.P. A Mass-Tolerant Database Search Identifies a Large Proportion of Unassigned Spectra in Shotgun Proteomics as Modified Peptides. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Na, S.; Bandeira, N.; Paek, E. Fast Multi-Blind Modification Search through Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2012, 11, M111.010199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Li, N.; Yu, W. PIPI: PTM-Invariant Peptide Identification Using Coding Method. J. Proteome Res. 2016, 15, 4423–4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, A.T.; Leprevost, F.V.; Avtonomov, D.M.; Mellacheruvu, D.; Nesvizhskii, A.I. MSFragger: Ultrafast and Comprehensive Peptide Identification in Mass Spectrometry–Based Proteomics. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devabhaktuni, A.; Lin, S.; Zhang, L.; Swaminathan, K.; Gonzalez, C.G.; Olsson, N.; Pearlman, S.M.; Rawson, K.; Elias, J.E. TagGraph Reveals Vast Protein Modification Landscapes from Large Tandem Mass Spectrometry Datasets. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, T.; Wehner, A.; Schaab, C.; Cox, J.; Mann, M. Comparative proteomic analysis of eleven common cell lines reveals ubiquitous but varying expression of most proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteom. MCP 2012, 11, M111.014050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, D.; Tsai, T.-H.; Verschueren, E.; Huang, T.; Hinkle, T.; Phu, L.; Choi, M.; Vitek, O. MSstatsPTM: Statistical Relative Quantification of Posttranslational Modifications in Bottom-Up Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteom. MCP 2023, 22, 100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitsky, L.I.; Klein, J.A.; Ivanov, M.V.; Gorshkov, M.V. Pyteomics 4.0: Five Years of Development of a Python Proteomics Framework. J. Proteome Res. 2019, 18, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goloborodko, A.A.; Levitsky, L.I.; Ivanov, M.V.; Gorshkov, M.V. Pyteomics—A Python Framework for Exploratory Data Analysis and Rapid Software Prototyping in Proteomics. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2013, 24, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulstaert, N.; Shofstahl, J.; Sachsenberg, T.; Walzer, M.; Barsnes, H.; Martens, L.; Perez-Riverol, Y. ThermoRawFileParser: Modular, Scalable, and Cross-Platform RAW File Conversion. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutet, E.; Lieberherr, D.; Tognolli, M.; Schneider, M.; Bansal, P.; Bridge, A.J.; Poux, S.; Bougueleret, L.; Xenarios, I. UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot, the Manually Annotated Section of the UniProt KnowledgeBase: How to Use the Entry View; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 23–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, C.-R.; Tang, Y.; Chiu, Y.-P.; Li, S.; Hsieh, W.-K.; Yao, L.; Chiang, Y.-C.; Pang, Y.; Chen, G.-T.; Chou, K.-C.; et al. DbPTM 2025 Update: Comprehensive Integration of PTMs and Proteomic Data for Advanced Insights into Cancer Research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D377–D386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitsky, L.I.; Ivanov, M.V.; Lobas, A.A.; Bubis, J.A.; Tarasova, I.A.; Solovyeva, E.M.; Pridatchenko, M.L.; Gorshkov, M.V. IdentiPy: An Extensible Search Engine for Protein Identification in Shotgun Proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 2018, 17, 2249–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, M.V.; Levitsky, L.I.; Bubis, J.A.; Gorshkov, M.V. Scavager: A Versatile Postsearch Validation Algorithm for Shotgun Proteomics Based on Gradient Boosting. Proteomics 2019, 19, e1800280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leprevost, F.d.V.; Haynes, S.E.; Avtonomov, D.M.; Chang, H.-Y.; Shanmugam, A.K.; Mellacheruvu, D.; Kong, A.T.; Nesvizhskii, A.I. Philosopher: A versatile toolkit for shotgun proteomics data analysis. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 869–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiszler, D.J.; Kong, A.T.; Avtonomov, D.M.; Yu, F.; Leprevost, F.d.V.; Nesvizhskii, A.I. PTM-Shepherd: Analysis and Summarization of Post-Translational and Chemical Modifications From Open Search Results. Mol. Cell. Proteom. MCP 2021, 20, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Yadav, A.K. False Discovery Rate Estimation in Proteomics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1362, 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Szabo, Z.; Janaky, T. Challenges and Developments in Protein Identification Using Mass Spectrometry. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2015, 69, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, P.; Goslinga, J.; Kooren, J.A.; McGowan, T.; Wroblewski, M.S.; Seymour, S.L.; Griffin, T.J. A Two-step Database Search Method Improves Sensitivity in Peptide Sequence Matches for Metaproteomics and Proteogenomics Studies. Proteomics 2013, 13, 1352–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Strogov, Y.Y.; Spirin, S.A.; Ivanov, M.V.; Kulebyakina, M.A.; Efimenko, A.Y.; Klychnikov, O.I. PTMs_Closed_Search: Multiple Post-Translational Modification Closed Search Using Reduced Search Space and Transferred FDR. Proteomes 2026, 14, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes14010007

Strogov YY, Spirin SA, Ivanov MV, Kulebyakina MA, Efimenko AY, Klychnikov OI. PTMs_Closed_Search: Multiple Post-Translational Modification Closed Search Using Reduced Search Space and Transferred FDR. Proteomes. 2026; 14(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes14010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrogov, Yury Yu., Sergey A. Spirin, Mark V. Ivanov, Maria A. Kulebyakina, Anastasia Yu. Efimenko, and Oleg I. Klychnikov. 2026. "PTMs_Closed_Search: Multiple Post-Translational Modification Closed Search Using Reduced Search Space and Transferred FDR" Proteomes 14, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes14010007

APA StyleStrogov, Y. Y., Spirin, S. A., Ivanov, M. V., Kulebyakina, M. A., Efimenko, A. Y., & Klychnikov, O. I. (2026). PTMs_Closed_Search: Multiple Post-Translational Modification Closed Search Using Reduced Search Space and Transferred FDR. Proteomes, 14(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes14010007