Proteomics and Bioinformatics Profiles of Human Mesothelial Cell Line MeT-5A

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Proteome Preparation

2.2. Conditioned Medium Proteome Preparation

2.3. Liquid Chromatography

2.4. Mass Spectrometry

2.5. Protein Identification and Data Search Parameters

2.6. Proteome Functional Classification Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Proteome Annotation Based on Gene Ontology (GO) Terms

3.1.1. GO Cellular Component Enrichment

3.1.2. GO Molecular Function Enrichment

3.1.3. GO Bioprocess Enrichment

3.2. Protein Domain

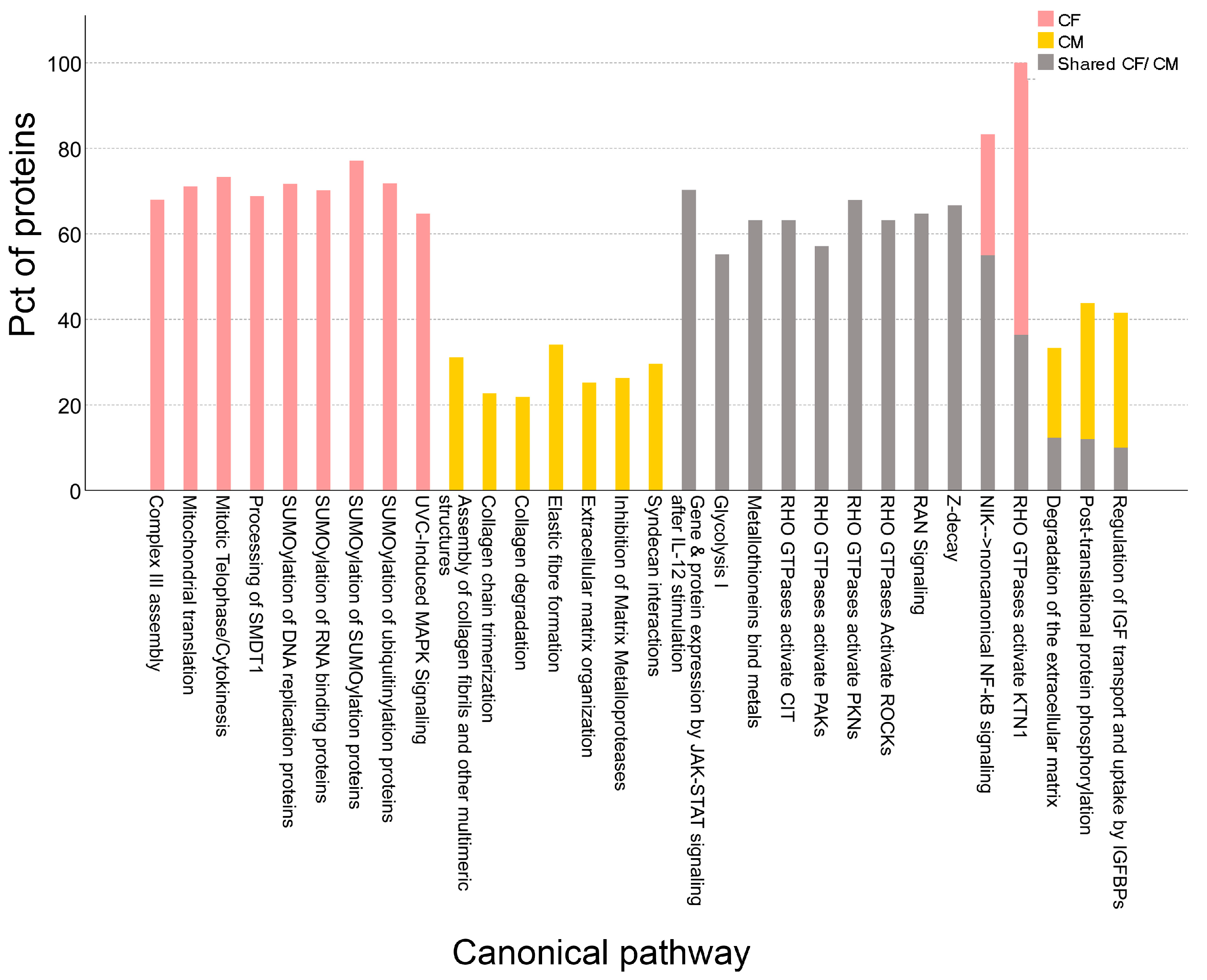

3.3. Canonical Pathway Enrichment

3.4. Shared Proteins Between MeT-5A and Innate Immunity

Study Limitations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koopmans, T.; Rinkevich, Y. Mesothelial to mesenchyme transition as a major developmental and pathological player in trunk organs and their cavities. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsaers, S.E. Mesothelial cells: Their structure, function and role in serosal repair. Respirology 2002, 7, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, S.; Thomas, G.J.; Stylianou, E.; Williams, J.D.; Coles, G.A.; Davies, M. Source of peritoneal proteoglycans. Human peritoneal mesothelial cells synthesize and secrete mainly small dermatan sulfate proteoglycans. Am. J. Pathol. 1995, 146, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nasreen, N.; Hartman, D.L.; Mohammed, K.A.; Antony, V.B. Talc-induced expression of C-C and C-X-C chemokines and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in mesothelial cells. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 158, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visser, C.E.; Steenbergen, J.J.; Betjes, M.G.; Meijer, S.; Arisz, L.; Hoefsmit, E.C.; Krediet, R.T.; Beelen, R.H. Interleukin-8 production by human mesothelial cells after direct stimulation with staphylococci. Infect. Immun. 1995, 63, 4206–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawanishi, K. Diverse properties of the mesothelial cells in health and disease. Pleura Peritoneum 2016, 1, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsaers, S.E.; Pixley, F.J.; Prele, C.M.; Hoyne, G.F. Mesothelial cells regulate immune responses in health and disease: Role for immunotherapy in malignant mesothelioma. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2020, 64, 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsaers, S.E.; Whitaker, D.; Papadimitriou, J.M. Changes in the concentration of microvilli on the free surface of healing mesothelium are associated with alterations in surface membrane charge. J. Pathol. 1996, 180, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantz, M.A.; Antony, V.B. Pleural fibrosis. Clin. Chest Med. 2006, 27, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotev, Z.; Whitaker, D.; Papadimitriou, J.M. Role of macrophages in mesothelial healing. J. Pathol. 1987, 151, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, R.; Yin, Y.; Wang, X. Mesothelial and immune cells interplay in the tumor microenvironment. Trends Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G.; Dufour, J.M. Cell lines: Valuable tools or useless artifacts. Spermatogenesis 2012, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voloshin, N.; Tyurin-Kuzmin, P.; Karagyaur, M.; Akopyan, Z.; Kulebyakin, K. Practical Use of Immortalized Cells in Medicine: Current Advances and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalak, M.; Hesaraki, M.; Mirbahari, S.N.; Yeganeh, M.; Abdi, S.; Rajabi, S.; Hemmatzadeh, F. Cell Immortality: In Vitro Effective Techniques to Achieve and Investigate Its Applications and Challenges. Life 2024, 14, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Kumar, C.; Bohl, S.; Klingmueller, U.; Mann, M. Comparative proteomic phenotyping of cell lines and primary cells to assess preservation of cell type-specific functions. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2009, 8, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, E.; Poulos, R.C.; Cai, Z.; Barthorpe, S.; Manda, S.S.; Lucas, N.; Beck, A.; Bucio-Noble, D.; Dausmann, M.; Hall, C.; et al. Pan-cancer proteomic map of 949 human cell lines. Cancer Cell 2022, 40, 835–849.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusinow, D.P.; Szpyt, J.; Ghandi, M.; Rose, C.M.; McDonald, E.R., 3rd; Kalocsay, M.; Jane-Valbuena, J.; Gelfand, E.; Schweppe, D.K.; Jedrychowski, M.; et al. Quantitative Proteomics of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Cell 2020, 180, 387–402.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegmans, J.P.; Bard, M.P.; Hemmes, A.; Luider, T.M.; Kleijmeer, M.J.; Prins, J.B.; Zitvogel, L.; Burgers, S.A.; Hoogsteden, H.C.; Lambrecht, B.N. Proteomic analysis of exosomes secreted by human mesothelioma cells. Am. J. Pathol. 2004, 164, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacnun, J.M.; Herzog, R.; Kratochwill, K. Proteomic study of mesothelial and endothelial cross-talk: Key lessons. Expert. Rev. Proteom. 2022, 19, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, J.R.; Zougman, A.; Nagaraj, N.; Mann, M. Universal sample preparation method for proteome analysis. Nat. Methods 2009, 6, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohannes, E.; Kazanjian, A.A.; Lindsay, M.E.; Fujii, D.T.; Ieronimakis, N.; Chow, G.E.; Beesley, R.D.; Heitmann, R.J.; Burney, R.O. The human tubal lavage proteome reveals biological processes that may govern the pathology of hydrosalpinx. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohannes, E.; Ippolito, D.L.; Damicis, J.R.; Dornisch, E.M.; Leonard, K.M.; Napolitano, P.G.; Ieronimakis, N. Longitudinal Proteomic Analysis of Plasma across Healthy Pregnancies Reveals Indicators of Gestational Age. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseka, P.; Pathan, M.; Chitti, S.V.; Kang, T.; Mathivanan, S. FunRich enables enrichment analysis of OMICs datasets. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 166747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziol, J.; Griffin, N.; Long, F.; Li, Y.; Latterich, M.; Schnitzer, J. On protein abundance distributions in complex mixtures. Proteome Sci. 2013, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Weng, Y.; Sui, Z.; Wu, Y.; Meng, X.; Wu, M.; Jin, H.; Tan, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Quantitative secretomic analysis of pancreatic cancer cells in serum-containing conditioned medium. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, R.; Nakajima, D.; Sato, H.; Endo, Y.; Ohara, O.; Kawashima, Y. A Simple Method for In-Depth Proteome Analysis of Mammalian Cell Culture Conditioned Media Containing Fetal Bovine Serum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didiasova, M.; Schaefer, L.; Wygrecka, M. When Place Matters: Shuttling of Enolase-1 Across Cellular Compartments. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz-Ramos, A.; Roig-Borrellas, A.; Garcia-Melero, A.; Lopez-Alemany, R. alpha-Enolase, a multifunctional protein: Its role on pathophysiological situations. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 156795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, K.; Dong, C.; Yin, Z.; Li, R.; Mao, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Z.; Liang, R.; Wang, Q.; et al. Exosome-derived ENO1 regulates integrin alpha6beta4 expression and promotes hepatocellular carcinoma growth and metastasis. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, N.; Won, C.; Kim, H.R.; Hwang, Y.I.; Song, Y.W.; Kang, J.S.; Lee, W.J. alpha-Enolase expressed on the surfaces of monocytes and macrophages induces robust synovial inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.K.; Sun, Y.; Lv, L.; Ping, Y. ENO1 and Cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2022, 24, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickel, W. Pathways of unconventional protein secretion. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010, 21, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maricchiolo, E.; Panfili, E.; Pompa, A.; De Marchis, F.; Bellucci, M.; Pallotta, M.T. Unconventional Pathways of Protein Secretion: Mammals vs. Plants. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 895853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, X.; Hu, S.; Duan, K.; Chen, T.; Li, W.; Sun, X.; Li, P.; Wang, P.; et al. Tumor exosomal circPTBP3 drives gastric cancer peritoneal metastasis via mesothelial-mesenchymal transition. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arita, T.; Ichikawa, D.; Konishi, H.; Komatsu, S.; Shiozaki, A.; Ogino, S.; Fujita, Y.; Hiramoto, H.; Hamada, J.; Shoda, K.; et al. Tumor exosome-mediated promotion of adhesion to mesothelial cells in gastric cancer cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 56855–56863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Anton, L.; Cardenes, B.; Sainz de la Cuesta, R.; Gonzalez-Cortijo, L.; Lopez-Cabrera, M.; Cabanas, C.; Sandoval, P. Mesothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition and Exosomes in Peritoneal Metastasis of Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsaers, S.E.; Birnie, K.; Lansley, S.; Herrick, S.E.; Lim, C.B.; Prele, C.M. Mesothelial cells in tissue repair and fibrosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, R.M.; Crouch, E.C. Role of mesothelial and submesothelial stromal cells in matrix remodeling following pleural injury. Am. J. Pathol. 1993, 142, 547–555. [Google Scholar]

- Valiente-Alandi, I.; Schafer, A.E.; Blaxall, B.C. Extracellular matrix-mediated cellular communication in the heart. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2016, 91, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyanka, P.P.; Yenugu, S. Coiled-Coil Domain-Containing (CCDC) Proteins: Functional Roles in General and Male Reproductive Physiology. Reprod. Sci. 2021, 28, 2725–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, A.; Schraegle, S.J.; Stahlberg, E.A.; Meier, I. Coiled-coil protein composition of 22 proteomes--differences and common themes in subcellular infrastructure and traffic control. BMC Evol. Biol. 2005, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, A.; Denecke, J. The endoplasmic reticulum-gateway of the secretory pathway. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, K.; Shioya, R.; Nishino, K.; Furihata, H.; Hijikata, A.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y.; Shirai, T.; Kosako, H.; Sawasaki, T. Proximity extracellular protein-protein interaction analysis of EGFR using AirID-conjugated fragment of antigen binding. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piperigkou, Z.; Mangani, S.; Koletsis, N.E.; Koutsakis, C.; Mastronikolis, N.S.; Franchi, M.; Karamanos, N.K. Principal mechanisms of extracellular matrix-mediated cell-cell communication in physiological and tumor microenvironments. FEBS J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seif, F.; Khoshmirsafa, M.; Aazami, H.; Mohsenzadegan, M.; Sedighi, G.; Bahar, M. The role of JAK-STAT signaling pathway and its regulators in the fate of T helper cells. Cell Commun. Signal 2017, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Bian, Q.; Rong, D.; Wang, L.; Song, J.; Huang, H.S.; Zeng, J.; Mei, J.; Wang, P.Y. JAK/STAT pathway: Extracellular signals, diseases, immunity, and therapeutic regimens. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1110765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonia, B.; Xavier, C.P.R.; Kopecka, J.; Riganti, C.; Vasconcelos, M.H. The role of Extracellular Vesicles in glycolytic and lipid metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells: Consequences for drug resistance. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 2023, 73, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goran Ronquist, K. Extracellular vesicles and energy metabolism. Clin. Chim. Acta 2019, 488, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, R.E.; Mpilla, G.; Kim, S.; Philip, P.A.; Azmi, A.S. Ras and exosome signaling. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2019, 54, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klement, E.; Medzihradszky, K.F. Extracellular Protein Phosphorylation, the Neglected Side of the Modification. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2017, 16, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliabracci, V.S.; Wiley, S.E.; Guo, X.; Kinch, L.N.; Durrant, E.; Wen, J.; Xiao, J.; Cui, J.; Nguyen, K.B.; Engel, J.L.; et al. A Single Kinase Generates the Majority of the Secreted Phosphoproteome. Cell 2015, 161, 1619–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, S.; Sroga, G.E.; Hoac, B.; Katsamenis, O.L.; Wang, Z.; Bouropoulos, N.; McKee, M.D.; Sorensen, E.S.; Thurner, P.J.; Vashishth, D. The role of extracellular matrix phosphorylation on energy dissipation in bone. Elife 2020, 9, e58184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, H.N.; Tomlin, D.; Ricke, W.A.; Li, L. Integrating intracellular and extracellular proteomic profiling for in-depth investigations of cellular communication in a model of prostate cancer. Proteomics 2023, 23, e2200287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Watkin, R.L.; Kazanjian, A.A.; Damicis, J.R.; Yohannes, E. Proteomics and Bioinformatics Profiles of Human Mesothelial Cell Line MeT-5A. Proteomes 2026, 14, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes14010002

Watkin RL, Kazanjian AA, Damicis JR, Yohannes E. Proteomics and Bioinformatics Profiles of Human Mesothelial Cell Line MeT-5A. Proteomes. 2026; 14(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes14010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleWatkin, Rachel L., Avedis A. Kazanjian, Jennifer R. Damicis, and Elizabeth Yohannes. 2026. "Proteomics and Bioinformatics Profiles of Human Mesothelial Cell Line MeT-5A" Proteomes 14, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes14010002

APA StyleWatkin, R. L., Kazanjian, A. A., Damicis, J. R., & Yohannes, E. (2026). Proteomics and Bioinformatics Profiles of Human Mesothelial Cell Line MeT-5A. Proteomes, 14(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes14010002