Utilising the Social Return on Investment (SROI) Framework to Gauge Social Value in the Fast Forward Program

Abstract

:1. Introduction

The Australian Higher Education System

2. Literature Review

2.1. School Experiences and Widening Participation

2.2. Non-Traditional Students’ Engagement with Higher Education

2.3. Student Disengagement and Higher Education

2.4. Comparative Evaluations of Widening Participation Programs

3. Methodology

- A means of measuring the social impacts of projects, programs, organizations, businesses, and policies;

- A form of stakeholder-driven evaluation blended with cost-benefit analysis tailored to social purposes.

- Involve stakeholders. Stakeholders (i.e., participants) inform what is considered meaningful to the FFP within their context and how the program is measured and valued.

- Understand what changes. Describing how change has happened as a result of the FFP. This change is not limited to positive and intended change, but also includes negative and unintended change. These changes are understood as outcomes, which form a theory of change—how FFP has impacted the community, and how these changes are measured for all participants. Each outcome is measured through indicators, validating their effectiveness.

- Value the things that matter. Outcomes such as increased aspiration and motivation are given financial proxies in order to value how the outcomes can be measured quantitatively.

- Only include what is material. Deciding what information needs to be included when assessing the program, so that an accurate picture of the program’s impact can be ascertained. This step uses the term ‘materiality’, where “information is material if missing it out of the SROI would misrepresent the [program’s] activities” [26], p. 9.

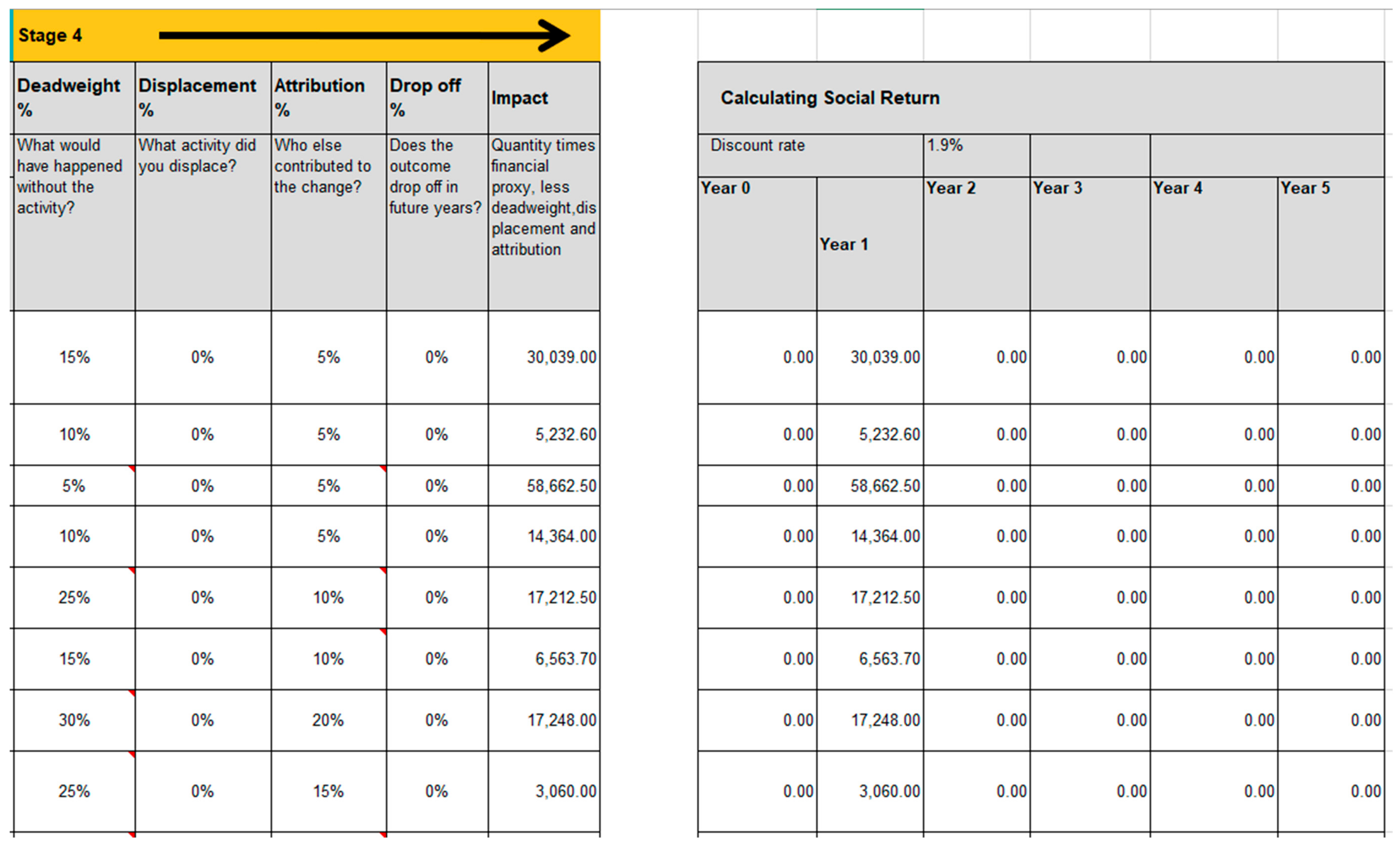

- Do not overclaim. This analysis claims only what FFP is responsible for. An example of overclaiming would be attributing an increase in motivation to the program when in fact students’ parents have continuously encouraged university participation throughout their schooling careers. Deadweight refers to the amount, expressed as a percentage, of the outcomes that would have happened without Fast Forward being present in the school. Attribution is similar to deadweight, except that it measures if/how these outcomes would have been met by other people (students, parents, teachers, other influences). The final consideration in this section is drop-off, which measures how the impact of the outcomes depreciate over time, especially the outcomes that are derived solely from the FFP. It may be that, over time, other factors or influences impact the participants more than the program itself. Drop-off is considered for outcomes that last for more than one year; this analysis considers the impact of the program for only one year (2017), and thus drop-off was not applied in this analysis.

- Be transparent. Reflect the honest perspectives of research participants, as well as the authors’ position as those who want to show FFP to be an effective program. At this point, theory of change is developed, showing the processes of change that have occurred, and how this has led to outcomes being met. The SROI ratio of money invested—money gained, on the basis of the commodification of the outcomes as material—is also developed at this point, which highlights the economic impact of the program whilst drawing upon the social, educational, and other outcomes that have been delivered as a result of the program.

- Verify the result. Present findings to all stakeholders via emailing a two-page report to school representatives, which was distributed to those that took part in the research.

3.1. Step 1: Involve Stakeholders

3.1.1. Year 9

3.1.2. Year 10

3.1.3. Year 11

3.1.4. Year 12

3.1.5. Parents

3.1.6. Project Officers and Western Sydney University Support Staff

4. Findings

4.1. What Are the Best Parts of Being Involved in the FFP?

4.1.1. Students

Fast Forward is a program that looks out for students like myself who is [sic] worried about their university/future.

I believe that I can achieve university and that it is not a scary place.

Giving me the opportunity to succeed and reach my full potential and to show that disability doesn’t prove anything and to take on anything that comes your way.

It motivates me to get great marks to get into university, and it also builds my leadership, communication skills and confidence.

Learning alot [sic] of different skills and learning alot [sic] about the University. Before I attended this program, I was kind of scared about university but now I’m very confident thanks to Fast Forward.

We are experiencing how university life is like and the teaching. There is always someone to guide you and you can ask them questions about university.

We get to learn about university, I did not know what I wanted to do but now I have somewhat of an idea. We learn and we have fun. Fast Forward helps me with my future.

Fast Forward provides a massive support system in my opinion. It’s incredibly encouraging and motivates me to graduate and make it to uni. I also really enjoy the workshops, they provide knowledge you can’t just google to learn about.

Being able to gain an insight into a true Uni lifestyle. Having the opportunity to visit the campus and experience lectures and talks. Gaining a sense of motivation for not only Uni life, but other aspects of general life.

4.1.2. Parents

Getting to see how the uni is set-up [sic] and finding out about courses available for my daughter.

My daughter has a better understanding of University life and how to navigate her pathway to her chosen career.

4.1.3. Project Officers

Seeing students really connect with a particular activity or actively engage in the learning process is most rewarding. Witnessing staff appreciation for the work we do reinforces the value of the programs.

The best part of the…program is developing a relationship with participants over the four years they participate in the program and noticing their progress and improvement…I feel that I can have a significant impact on…[their] career[s] and steering decisions…

Watching the students’ faces when they realise it is not that difficult and that others have overcome difficulty to get to uni. Hearing comments like, “now I know what I want to do” and “this is the first time I have looked up different jobs and thought about them”.

4.1.4. Western Sydney University Support Staff

You are reminded why you began your own journey, you have a chance to pay it forward and tell your younger self a few things you wish someone had told you. You are involved in possibly inspiring someone great during their more confused and younger years.

Not only does the program build aspirations for young people to access and be successful at their current schooling and university, but it also creates a platform that celebrates and validates the experiences of academic staff to share their life journeys with the next generation.

4.2. What Did You Learn from Being Involved in the FFP?

4.2.1. Students

I have learnt alot [sic] from Fast Forward, especially from the online website (YourTutor, now known as Studiosity, is an online tutoring service that connects students to teachers to help with Mathematics, English, Science and other subject areas. More information can be found at https://www.studiosity.com/.) helped me with my exams and NAPLAN [National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy].

The Fast Forward Program has taught me how to balance school and life.

I have learned that there are many opportunities for us when we go to university. I have also learned that the uni staff care about young students studying and education.

To work with others to be independent[,] develop my life skills[,] have tudors [sic] to help me whenever I need them.

I learnt so many spectacular things about university, I learnt how to be more involved as well as making new friends and I also learnt that going to university is the one of the greatest achievement especially in our western Sydney region.

I have learned that going to Uni is hard and I have to study hard and get good mark and if I try my best it’s not gonna be hard and impossible as I though[t] it would be.

The Fast Forward Program has taught me how to interact and participate more, it also taught me how to achieve my goals in order to achieve my dream job.

I’ve learned how to be capable with everyday life…Doing harder in school work and achieve my goals or getting high ATAR (Australian Tertiary Admission Rank, which is the primary factor used to determine university entry in Australia, showing a comparative rank between all Year 12 students. It is expressed as a two-digit, two decimal figure, with 99.95 being the highest score).

To be a good leader, to understand all aspects of how to stay focussed. How to further myself.

There is more than one way to achieve your goals and failing is okay as it helps us grow and make us appreciate things a lot more.

I’ve learned that university isn’t as difficult as I’ve been told. I’ve also learned to recognise and use my great abilities. I’ve also learned that failure isn’t bad, in fact it’s NECESSARY in order to succeed.

Different opportunities available for life after school which has heavily impacted my view and understanding on what I am capable of.

4.2.2. Parents

4.2.3. Project Officers

I have been reminded of how little careers ed[ucation] is done before Year 12 in some schools, which means many students are very confused at subject selection time. Their ability to choose subjects to suit their interests competes with pressure to pick subjects for a good ATAR or for uni, when they may change which course they want to do. Schools vary greatly in the quality of the Careers Advisor.

4.2.4. Western Sydney University Support Staff

We hold a position of trust and authority and to treat that with respect and care when influencing young minds.

4.3. Step 2: Value the Things That Matter

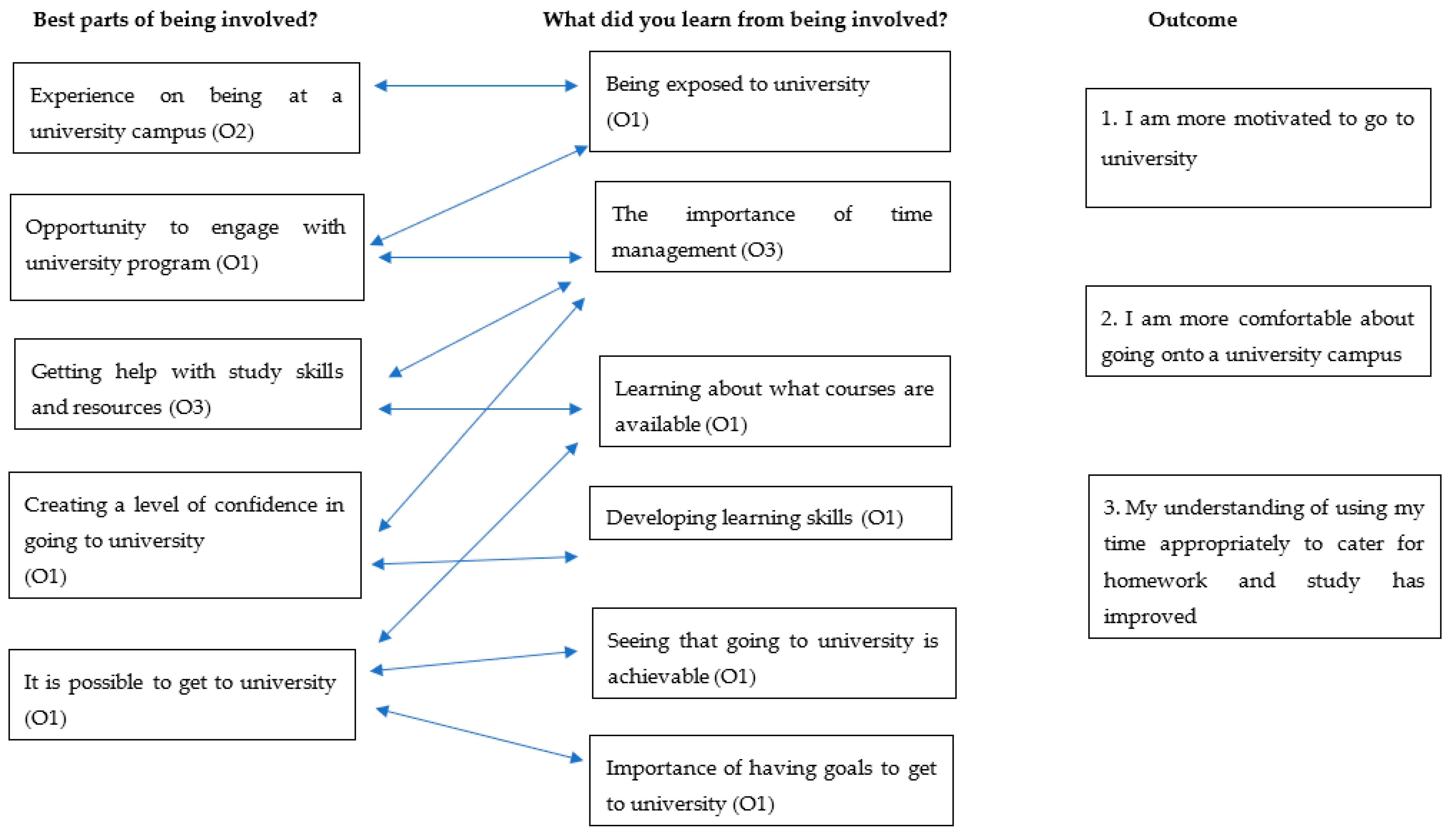

4.3.1. Year 9

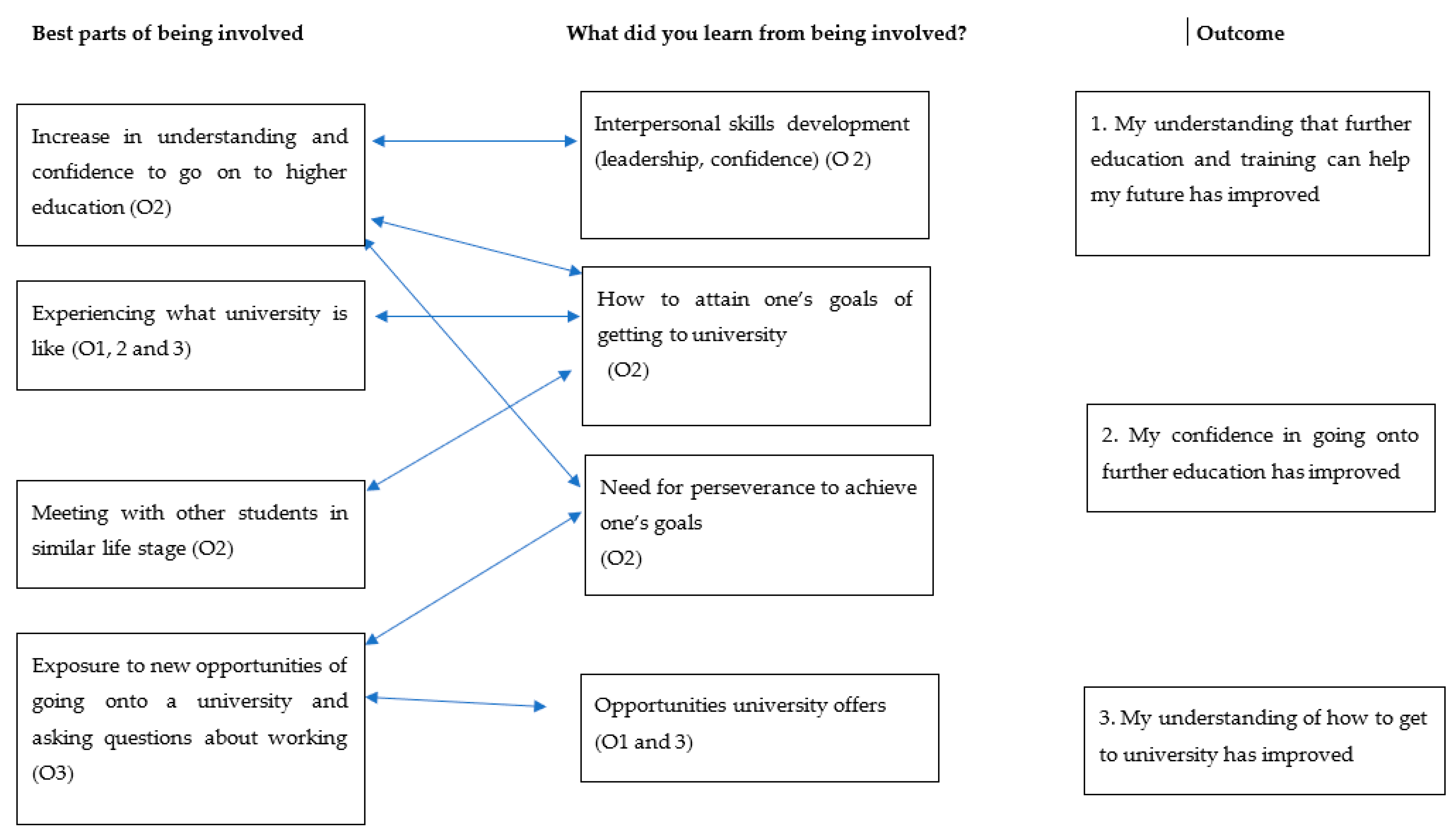

4.3.2. Year 10

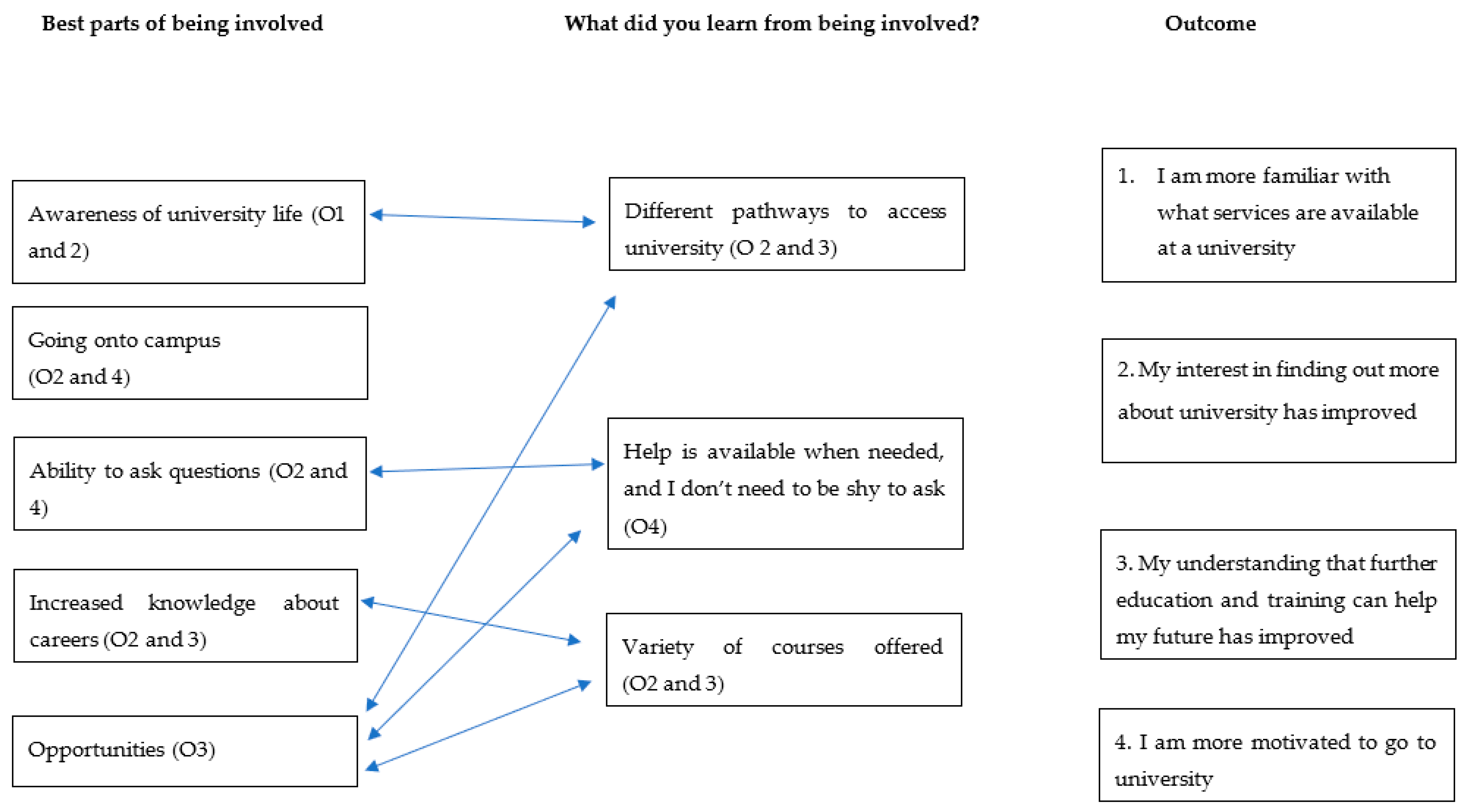

4.3.3. Year 11

4.3.4. Year 12

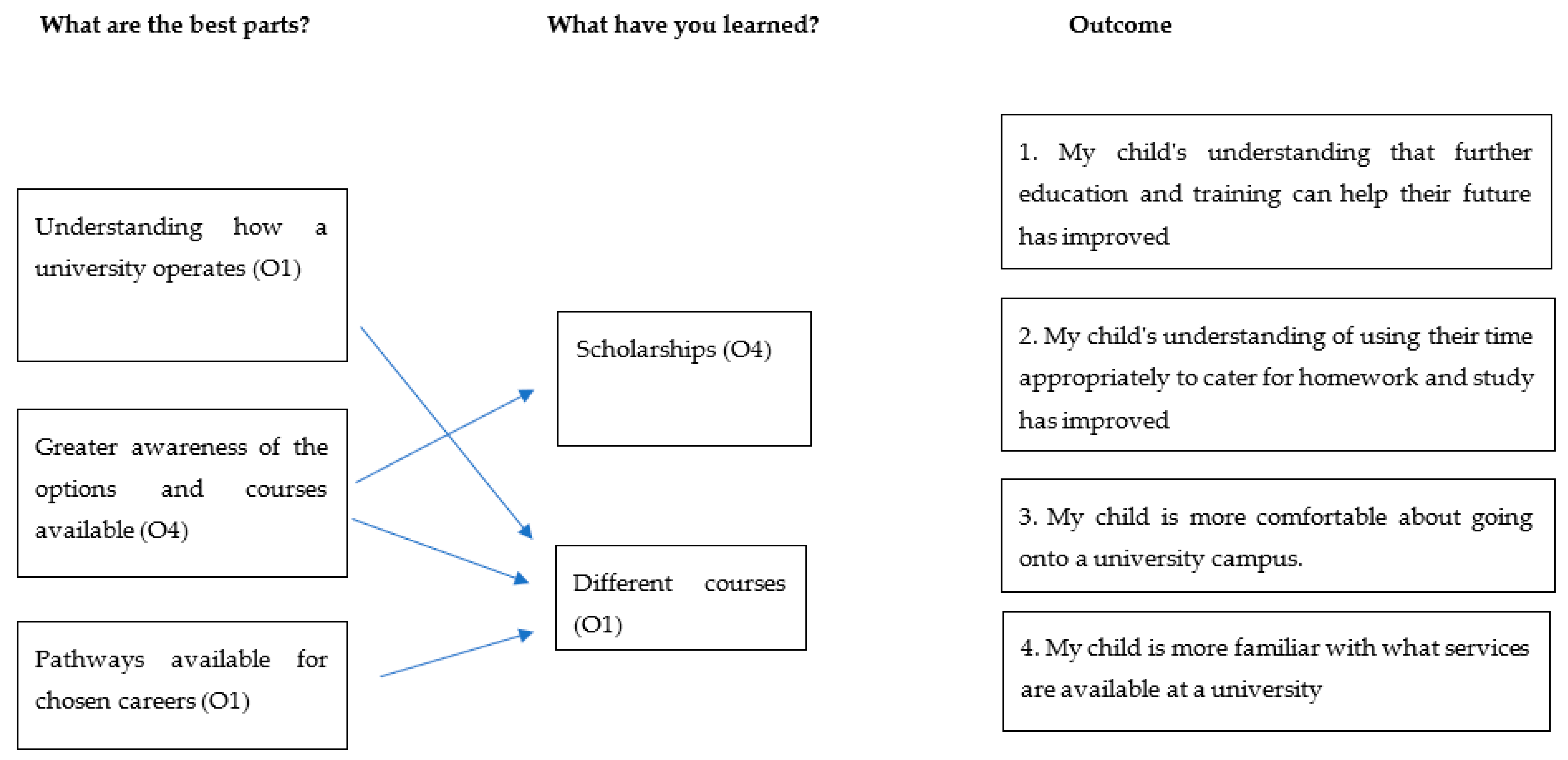

4.3.5. Parents

4.3.6. Project Officers

4.3.7. WSU Support Staff

4.4. As a Result of Being in the FFP, What Areas Have Improved and What Areas Have Changed?

4.4.1. Year 9

4.4.2. Year 10

4.4.3. Year 11

4.4.4. Year 12

4.4.5. Parents

4.4.6. Project Officers

4.4.7. WSU Support Staff

4.5. Step 3: Understand What Changes

4.6. Step 4: Include Only What Is Material

4.7. Step 5: Do Not Overclaim

4.8. Step 6: Be Transparent

4.9. Step 7: Verify the Result

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- KPMG. Evaluation of Bridges to Higher Education: Final Report. April 2015. Available online: https://www.bridges.nsw.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/898504/04302015Bridges_to_Higher_Education_Final_Report.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Universities Admissions Centre, Applying for uni through UAC. Available online: https://www.uac.edu.au/future-applicants/how-to-apply-for-uni (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- TAFE NSW, Apply for a Course. Available online: https://www.tafensw.edu.au/tafe-nsw (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- StudyAssist, HECS HELP. Available online: https://www.studyassist.gov.au/help-loans/hecs-help (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Birrell, B.; Edwards, D. The Bradley Review and access to higher education in Australia. Aust. Univ. Rev. 2009, 51, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, T.; Tranter, D. Social justice in Australian higher education policy: An historical and conceptual account of student participation. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2011, 52, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission. Higher Education; The Fair Access Challenge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Thiele, T.; Pope, D.; Singleton, A.; Snape, D.; Stanistreet, D. Experience of disadvantage: The influence of identity on engagement in working class students’ educational trajectories to an elite university. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2016, 43, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lumby, J. Disengaged and disaffected young people: Surviving the system. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2012, 38, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In Intergroup Relations: Essential Readings. Key Readings in Social Psychology; Hogg, M.A., Abrams, D., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; pp. 94–109. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, T. Let Them Eat Cake: Mobilising Appetites for Higher Education. In Proceedings of the Knowledge Works Public Lecture Series, Bradley Forum, Hawke Building, University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia, 3 June 2010; Available online: http://www.equity101.info/files/Gale_Final.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2019).

- Munro, L. ‘Go boldly, dream large!’: The challenges confronting non-traditional students at university. Aust. J. Educ. 2011, 55, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, J.; Devlin, M. ‘Uni has a different language … to the real world’: Demystifying academic culture and discourse for students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2014, 33, 949–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. Social Justice in the Age of Identity Politics: Redistribution, Recognition, and Participation. In Proceedings of the Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Delivered at Stanford University, United States of America, Stanford, CA, USA, 30 April–2 May 1996; Available online: https://tannerlectures.utah.edu/_documents/a-to-z/f/Fraser98.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Harwood, V.; O’Shea, S.; Uptin, J.; Humphry, N.; Kervin, L. Precarious Education and the University: Navigating the Silenced Borders of Participation. Int. J. Sch. Disaffection 2013, 10, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, S.; McKendrick, J.H.; Scott, G. Failing young people? Education and aspirations in a deprived community. Educ. Citizsh. Soc. Justice 2010, 5, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bielby, G.; Judkins, M.; O’Donnell, L.; McCrone, T. Review of the Curriculum and Qualification Needs of Young People who are at Risk of Disengagement; NFER Research Programme: From Education to Employment; NFER: Slough, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, G.; Elwood, J. The perspectives of “disengaged” students in the 14–19 phase on motivations and barriers to learning within the contexts of institutions and classrooms. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2013, 11, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCSEHE. Partnerships in Higher Education: Research Report 2014, Curtin University. Available online: https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/NCSEHE-Partnership-Publication-Web.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2019).

- Reed, R.; Karavias, S.; Smith, R. Investigating the Impact of Social Inclusion: A Case Study of Seven Widening Participation Programs at Macquarie University, (2013, October 16). National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education. Available online: https://www.ncsehe.edu.au/publications/investigating-impact-social-inclusion-macquarie/ (accessed on 16 October 2019).

- Bennett, A.; Naylor, R.; Mellor, K.; Brett, M.; Gore, J.; Harvey, A.; Munn, B.; James, R.; Smith, M.; Whitty, G. The Critical Interventions Framework Part Two Equity Initiatives in Australian Higher Education: A Review of Evidence of Impact. 2015. Available online: https://www.newcastle.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/261124/REPORT-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- Younger, K.; Gascoine, L.; Menzies, V.; Torgerson, C. A Systematic Review of Evidence on the Effectiveness of Interventions and Strategies for Widening Participation in Higher Education. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2019, 43, 742–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gore, J.; Holmes, K.; Smith, M.; Fray, L.; McElduff, P.; Weaver, N.; Wallington, C. Unpacking the career aspirations of Australian school students: Towards an evidence base for university equity initiatives in schools. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2017, 36, 1383–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reed, R.; King, A.; Whiteford, G. Re-conceptualising sustainable widening participation: Evaluation, collaboration and evolution. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2015, 34, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Ventures Australia. SROI Revolution or Evolution? 2019. Available online: https://www.socialventures.com.au/sva-quarterly/sroi-revolution-or-evolution/ (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Nicholls, J.; Lawlor, E.; Neitzert, E.; Goodspeed, T. A guide to Social Return on Investment. January 2012, p. 108. Available online: https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/aff3779953c5b88d53_cpm6v3v71.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Salverda, M. Social Return on Investment. BetterEvaluation, n.d. Available online: https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/approach/SROI (accessed on 24 November 2019).

- Schultheiss, D.E.P.; Blustein, D.L. Role of adolescent–parent relationships in college student development and adjustment. J. Couns. Psychol. 1994, 41, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandefur, G.D.; Meier, A.M.; Campbell, M.E. Family resources, social capital, and college attendance. Soc. Sci. Res. 2006, 35, 525–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, P.; Meghir, C.; Parey, M. Maternal education, home environments. And the development of children and adolescents. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2012, 11, 123–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Year | Activities in Program |

|---|---|

| Years 9–11 | One full day on campus (9:30–2:30); two to four workshops in school (1.5 h); Year 9 ‘Welcome to Western Evening’ (2 h). |

| Year 12 | One full day on campus (9:30–2:30); two to four workshops in school (1.5 h). Optional access to Higher School Certificate (HSC) preparation/attendance at Western Sydney University and open days. |

| Parents | Totalling 1 ‘Tertiary Information and Pathways’ session; 8 ‘Welcome to Western’ evenings (Year 9 parents); 12 evenings for parents of year 10–12 students (four workshops respectively for parents of each year). |

| Project officers | Four full-time (35 h per week) professional staff, comprising portfolios capturing an even division of the 63 of schools. |

| WSU support staff | Year 12 conference sessions. |

| Stakeholder Group | How Many? | Gender | Did Your Parent Attend University? | Do Your Parents Encourage You to Attend University? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 9 | 42 | 19 (47.50% male), 21 (52.50%) female | Mothers: 5 (12.50%) Fathers: 6 (15%) Both parents: 5 (12.50%) Neither: 11 (27.50%) Unsure: 13 (32.50%) | A lot: 24 (60%) Somewhat: 14 (35%) Not really: 2 (5%) |

| Year 10 | 26 | 11 (44%) male, 13 (52%) female, 1 (4%) other. | Mothers: 0 (0%) Fathers: 4 (15.38%) Both parents: 2 (7.69%) Neither: 17 (65.38%) Unsure: 3 (11.54%) | A lot: 12 (46.15%) Somewhat: 8 (30.77%) Not really: 6 (23.08%) |

| Year 11 | 19 | 5 (26.32% male, 14 (73.68%) female. | Mothers: 3 (16.67%) Fathers: 3 (16.67%) Both: 2 (11.11%) Neither: 10 (55.56%) | A lot:13 (68.42%) Somewhat: 6 (31.58%) |

| Year 12 | 13 | 3 (23.08%) male, 10 (76.92%) female. | Mothers: 3 (25%) Fathers: 0 (%) Both: 2 (16.67%) Neither: 7 (58.33%) | A lot: 9 (75%) Somewhat: 3 (25%) |

| Stakeholder Group | How Many? | Gender | How Long Have You Held Your Current Position? | Did You Encourage Your Child to Attend University Before the Fast Forward Program (FFP)? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents | 4 | 4 (100%) female | A lot: 1 (33%) Somewhat: 1 (33%) Not Really: 1 (33%) | |

| Project officers | 3 | 1 (33.33%) male, 2 (66.67%) female | 0–2 years: 3 (100%) | |

| WSU support staff | 2 | 2 female (100%) | 0–2 years: 1 (50%) 3–4 years: 1 (50%) |

| Question | Response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Lot | Somewhat | Not Really | Not Sure | |

| Completing high school by finishing year 12 | Year 9: 35 (89.74%) Year 10: 22 (84.62%) Year 11: 19 (100%) Year 12: 12 (100%) Project officers: 3 (100%) | Year 9: 4 (10.26%) Year 10: 4 (15.38%) | ||

| Finishing school before year 12 to get a job | ||||

| Going to university | Year 9: 28 (71.79%) Project officers: 3 (100%) WSU support staff: 1 (100%) | Year 9: 9 (23.08%) | Year 9: 2 (5.13%) | |

| Going to TAFE/college | ||||

| Getting into a job you are passionate about | Year 9: 35 (89.74%) Year 10: 23 (88.46%) Year 11: 17 (89.47%) Year 12: 12 (100%) Project officers: 3 (100%) Parents: 3 (100%) | Year 9: (10.26%) Year 10: 3 (11.54%) Year 11: 2 (10.53%) | ||

| Supporting your family | Year 9: 31 (79.49%) Year 11: 18 (94.74%) | Year 9: 8 (20.51%) Year 11: 1 (5.26%) | ||

| Participating in other sport and community commitments (e.g., church/cultural groups/dance, etc.) | Project officers: 3 (100%) | |||

| Being able to balance study, family, and community commitments (including household chores) | Year 12: 12 (100%) Parents: 3 (100%) Project officers: 3 (100%) WSU support staff: 1 (100%) | |||

| Being able to balance study and paid work commitments | Year 10: 18 (69.23%) Parents: 3 (100%) Project officers: 3 (100%) WSU support staff: 1 (100%) | Year 10: (30.77%) |

| Statement | Response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Following Areas Have Improved | ||||

| A Lot | Somewhat | Not Really | Not Sure | |

| My understanding of how to get into university | Year 10: 19 (73.08%) Project officers: 3 (100%) WSU support staff: 1 (100)% | Year 10: 7 (26.92%) | ||

| My understanding of how to get into TAFE/college | ||||

| My confidence in going onto further study | Year 10: 20 (76.92%) Year 12: 12 (100%) Project officers: 3 (100%) | Year 10: 6 (23.08%) | ||

| My interest in finding out more about going to university | Year 11: 14 (73.68%) Year 12: 11 (91.67%) Project officers: 3 (100%) | Year 11: 4 (21.05%) Year 12: 1 (8.33%) | Year 11: 1 (5.26%) | |

| My understanding that further education and training can help my future | Year 10: 22 (84.62%) Year 11: 14 (73.68%) Year 12: 11 (91.67%) Parents: 2 (66.67%) Project officers: 3 (100%) WSU support staff: 1 (100)% | Year 10: 4 (15.38%) Year 11: 4 (21.05%) Year 12: 1 (8.33%) Parents: 1 (33.33%) | Year 11: 1 (5.26%) | |

| My understanding of using my time appropriately to cater for homework and study | Year 9: 25 (64.10%) Year 12: 12 (100%) Parents: 2 (66.67%) Project officers: 3 (100%) WSU support staff: 1 (100%) | Year 9: 11 (28.21%) Parents: 1 (33.33%) | Year 9: 3 (7.69%) | |

| The Following Areas Have Changed | ||||

| A Lot | Somewhat | Not Really | Not Sure | |

| I am more comfortable about going onto a university campus | Year 9: 25 (64.10%) Parents: 2 (66.67%) Project officers: 3 (100%) WSU support staff: 1 (100)% | Year 9: 12 (30.77%) Parents: 1 (33.33%) | Year 9 2 (5.13%) | |

| I am more familiar with how a university operates | Year 11: 10 (52.63%) Project officers: 3 (100%) WSU support staff: 1 (100)% | Year 11: 9 (47.37%) | ||

| I am more familiar with what services are available at a university | Year 12: 11 (91.67%) Parents: 2 (66.67%) Project officers: 3 (100%) | Year 12: 1 (8.33%) Parents: 1 (33.33%) | ||

| I have more confidence to talk to my parents about university | WSU support staff: 1 (100)% | |||

| I am more motivated to go to university | Year 9: 31 (79.49%) Year 11: 14 (73.68%) Project officers: 3 (100%) WSU support staff: 1 (100)% | Year 9: 6 (15.38%) Year 11: 4 (21.05%) | Year 9: 2 (5.13%) Year 11: 1 (5.26%) | |

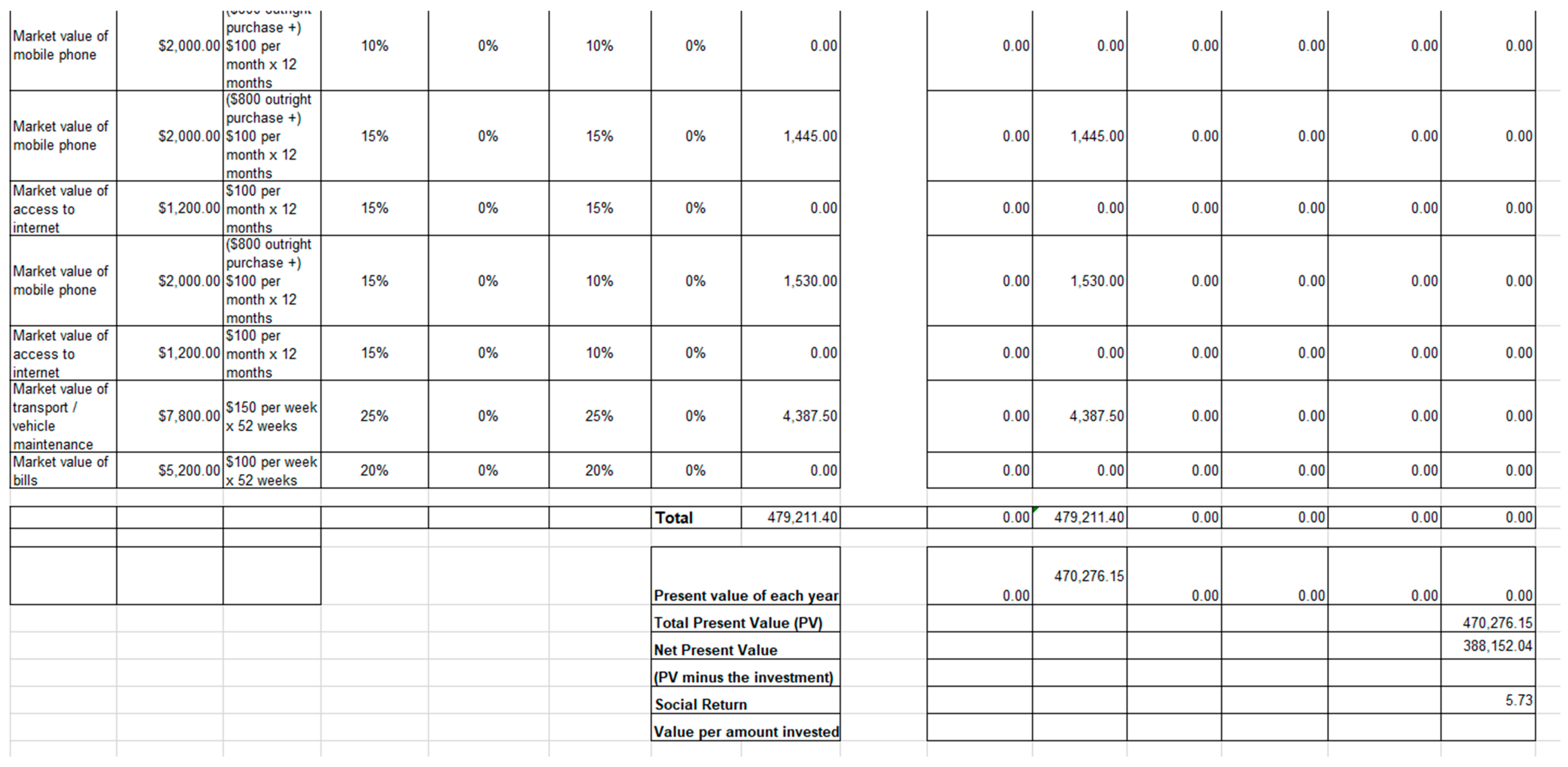

| Item | Cost Per Week | Calculation | Cost Per Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| $150 per week | $150 × 52 | $7800 |

| $6.21–$11.52 per hour | 12 h per week. Round up to $80–$140 a week, exact = 12 × $6.21−$11.52 = $74.52−$138.24 × 52 | $4160–$7280 |

| $50 per week | $50 × 52 | $2600 |

| $50 per week | $50 × 52 | $2600 |

| $800 outright purchase of phone; $50 credit per month | ($50 × 12) + 800 | $1400 |

| $100 per month | $100 × 12 | $1200 |

| $500 outright purchase of console; $10 per week | ($10 × 52) + 500 | $1200 |

| $15–$30 per week | $15 − $30 × 52 | $780–$1560 |

| Item | Cost Per Week | Calculation | Cost Per Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| $16.87–$46.21 per hour | 35–40 h per week. $16.87−$63.40 × 35−40 = $674.80−$2219 × 52 | $35,089.60–$115,388 |

| $600 per week | $600 × 52 | $31,200 |

| $150 per week | $150 × 52 | $7800 |

| $150 per week | $150 × 52 | $7800 |

| $100 per week | $100 × 52 | $5200 |

| $100 per week | $100 × 52 | $5200 |

| $50 per week | $50 × 52 | $2600 |

| $800 outright purchase; $100 credit per month | ($100 × 12) + $800 | $2000 |

| $100 per month | $100 × 12 | $1200 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ravulo, J.; Said, S.; Micsko, J.; Purchase, G. Utilising the Social Return on Investment (SROI) Framework to Gauge Social Value in the Fast Forward Program. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040290

Ravulo J, Said S, Micsko J, Purchase G. Utilising the Social Return on Investment (SROI) Framework to Gauge Social Value in the Fast Forward Program. Education Sciences. 2019; 9(4):290. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040290

Chicago/Turabian StyleRavulo, Jioji, Shannon Said, Jim Micsko, and Gayl Purchase. 2019. "Utilising the Social Return on Investment (SROI) Framework to Gauge Social Value in the Fast Forward Program" Education Sciences 9, no. 4: 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040290

APA StyleRavulo, J., Said, S., Micsko, J., & Purchase, G. (2019). Utilising the Social Return on Investment (SROI) Framework to Gauge Social Value in the Fast Forward Program. Education Sciences, 9(4), 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040290