1. Introduction

This paper confronts a significant conceptual deficit by using a novel interdisciplinary lens, Clarke’s Place Model [

1,

2], to deconstruct critically the term ‘professional’ and to reimagine a commodious and accessible conceptualization, consisting of five dystopias and a potentially potent oxymoron—

inclusive professional. Bourdieu’s [

3] argument that the term ‘professional’ should not even be used flew in the face of a reality in which professionals persisted and proliferated in (mostly) ingenuous defiance of one of the most eminent French public intellectuals of the age. He saw professional as a

folk concept which has been

smuggled into scientific language (p. 342, [

4]). Today, mapping a critical but polysemous understanding of professional is a matter of even greater urgency, in the light of enormously complex global challenges, the growing distrust of professionals which is a significant trend in a rising tide of populist political discourse, and the mounting concern that most of the traditional professions will be dismantled and replaced by a mixture of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and less expert, more flexible people to quote Susskind and Susskind [

5]. It may already be too late to save a chameleon term which is widely used in contexts of ambition, admiration and entreaty but is also viewed as inherently slippery, imbued with ambitions for high status and exclusivity, credentialism and over-regulation, and, as Gatenby observes, as a product of self-serving elitism [

6].

The word professional attracts many rhetorical ambiguities not least because it is often defined by its most shiny aspects and polished ideals. At the core of the ideal professional is sheer, often unsung, complex work—underpinned by a combination of two key attributes: expertise and trustworthiness. Professionals deserve to be believed because, unlike the laity, they are, in their respective fields, better at finding the truth. However, O’Neill notes that they will be trusted only to the extent that they are not deceitful and are trustworthy [

7]. Without this, a profession becomes what wrestling is to sport, a monetized and fabricated performance, which could be readily substituted by robotized AI. Meanwhile, Eliot Freidson’s [

8] alternatives to professionalism, his other two logics, bureaucracy and the market, are in the ascendancy, shaping both the professions and individual professionals. AI is posited as a further contextual logic here—one whose protean development looks set to encroach further on the place of professionals in ways which seem increasingly less than transparent or predictable. And yet, none of these alternative logics is sufficient for what we still want or need or demand from professionals—as, for example, in Bangladesh where Alhamdan, Al-Saadi, Baroutsis, Du Plessis, Hamid and Honan (p. 499, [

9]) state, an ideal ‘superhuman’ teacher is ‘neutral, kind hearted, friendly, knowledgeable, brave, sincere, dynamic, cordial, selfless, a motivator of children, attentive to students and unbiased, sincere, punctual and respectful’. By contrast, George Bernard Shaw decried all professions as merely conspiracies against the laity [

10]. Some distrust of professionals has persisted and a century later is being stoked by populist jingoism, although the term ‘laity’ is more rarely used in this context today. Nonetheless, it may be that we, the laities, are asking too much, even while decrying elitism and expense; offering the never-sufficient professional up to the tongue lashing of the demagogue, yet always wanting more from the teacher, the nurse, the academic, the doctor, the lawyer, the engineer, the social worker. It may be that we, the professionals, are asking too much, wanting to maintain an elite, inflexible and expensive place of esteem even while hoarding knowledge, excluding many talented people and hiding the fallibilities which can be exploited by the unscrupulous. We need a better map of this extensive but infinitely contestable place: the place of professionals—this paper aims to provide such a map.

The Place Model will be used to reimagine this important borderland between the world as it is and the world as it could be. Place was a salient idea for the Nobel Laureate, Seamus Heaney, in

The Herbal, Human Chain. Imagination allowed him to capture and share the landscapes of his life in one of his final poems … “I had my existence. I was there. Me in place and the place in me” [

11]. The Place Model maps a similarly embodied view of place, by speculatively redeploying Doreen Massey’s notion of

Geographical Imagination [

12] in which we can each map our own position, in our mind’s eye, in respect of two key dimensions: status and location. For the Chinese-American humanistic Geographer, Yi-Fu Tuan, these two senses of place are observably interrelated—for example, the status-place of a wealthy person is reflected in where he/she lives, the location of his/her table in a restaurant, and his/her position at the board table [

13]. The Place Model, likewise, juxtaposes two senses of place to achieve a timely,

a priori examination of the place of professionals:

place in the humanistic geography tradition as a process of expertise building—location in relation to the expanding horizon of a cumulative, career-long learning journey—and also,

place, in the sociological sense of esteem.

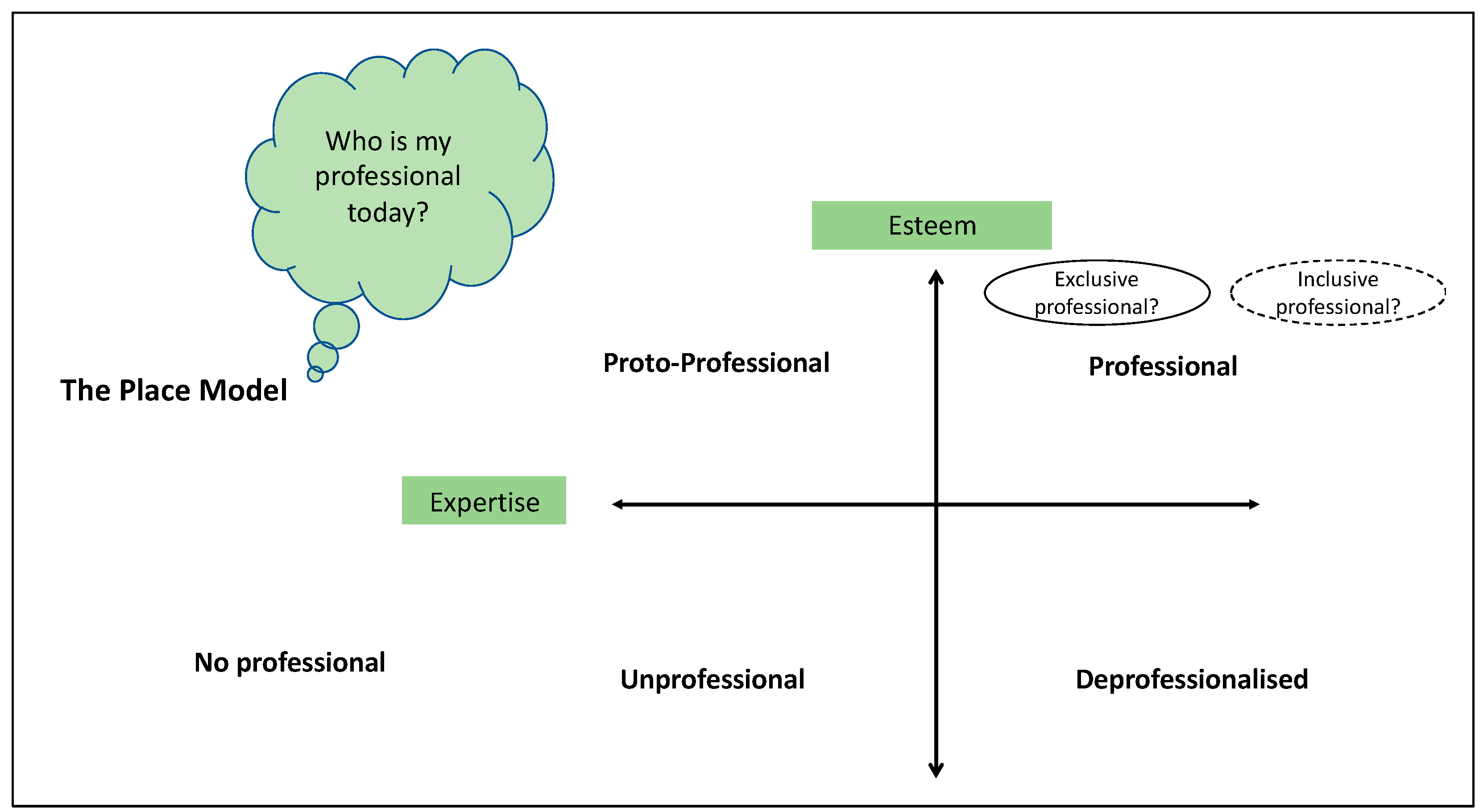

Combining these two senses of place provides an interdisciplinary framework for imaginative discourse which can yield a wide-ranging and challenging set of perspectives on professionals. Clarke [

14] admits that whilst “the Model is reductionist in nature (like many models), the Place Model presents a usefully uncluttered landscape which is mapped in a way that is intentionally schematic rather than mathematical in nature (although it does look like a graph), a heuristic rather than a positivist equation”. Here it is, once again, proffered as an interdisciplinary thinking tool for two key user groups: student professionals and their tutors. In preparing their students for their professional futures, tutors may invite them to consider critically their future learning journeys and status, across its terrain.

The Place Model will be used to consider and compare contemporary conceptions of professionals, and to provide an unconventional and original map, a conception which acknowledges the flaws while suggesting ideals and their limitations. The places within this landscape are strongly influenced by Freidson’s [

8] other two logics, to be outlined below, together with AI, a putative additional ‘logic’, in order to set the scene, before moving on to explore and populate the Place Model itself. This essay will focus on examples drawn from health, social care and education (the third one will dominate, reflecting the author’s professional learning journey) which have arguably been most strongly affected by the ascent and increasing dominance of these alternative logics. It is possible to apply the Place Model to all professions, even to politics and sports, where the term is used in quite different ways—where ‘professional’ can be an insult while being sufficiently elastic to describe both the player and the foul play. Unpacking these exceptional cases is quite another essay, as is a linguistic analysis of profession, professional and professionalism, which are treated here as grammatical variations of the same logic.

3. Components of the Place Model

The speech bubble below the heading of Place Model (

Figure 1 below) is significant because it links professionals to their respective laities by asking the question:

Who is my professional today? Clarke [

14] argues that

“The Model provides a usefully challenging range of answers based on comparing the two conceptions of place noted above by Massey as a

Geographical Imagination” [

12].

The horizontal ‘axis’ is based upon building expertise across one’s career. On the diagram (

Figure 1) this axis starts where a ‘new’ professional takes up their first job, but one might imagine that, putatively, on the most extreme left (well off the edge of the diagram) is the position of an egocentric baby, an extreme example of an incipient learner in its utterly Piagetian, “egocentric” [

26] world view. To the extreme right is the end of an expansive growth of expertise across a career, or series of careers. Clarke [

14] points out that “this axis is

not about terrestrial space—professional practice most often transpires locally and has local impacts, but the internet means that learning can readily become much more far wide-reaching in both depth and breadth. In addition, the axis is

not a timeline,

not a history, and it is

not a matter of passive survival for 30–40 years, gathering up a few tips and tricks about good practice on the way. Rather, the learning process is conceived as an expanding professional place”, using Tuan’s [

13] clear formula: “

Place =

Space +

Meaning”. The horizontal axis can be an extensive, complex and intricately featured place, built through cumulatively accreting processes of professional learning, an expanding horizon of Massey’s “

outwardlookingness” [

12]. As for Fullan argues [

27], “learning is the work”. Clarke [

14] argues that “This place may be conceived on either personal or profession-wide scales—an individual’s career or the systemic capacities for learning within a particular context, drawing on, and contributing to, a critical understanding of the best of what is known though the consumption of and/or the creation of relevant research”, with “particularly significant resonance with the early twenty-first century debates about professional status and regulation and marketization”. On the one hand, there are those who “promote a narrowly conceived technicist training approach which are linked to greater deregulation, flexibility and privatization (on the left-hand side of the axis), versus, on the other hand, the expansive professional education, predominantly within the master’s-level courses within college and university systems across the globe” [

14]. Clarke [

14] recognizes that “a key limitation of the Model is that the straight line of this axis cannot convey the ways in which careers are becoming more varied and more fragmented” and that “Imagination is needed here to conjure the cumulative, career-long learning journey which the increasingly dynamic nature of work demands—is there an inherent incompatibility between these demands, and the deep expertise and constant trustworthiness which are essential to professions?”

On the vertical axis, however, professionals often have much less agency as this depends on the constraints of public perceptions of esteem. The intersection of the status and learning axes alloows the creation of four quadrants which have been labelled as proto-professionals, precarious professionals, the de-professionalized and the professional. A fifth, equally important, element lies outside the axes, where the answer to the question ‘Who is my professional today?’ is ‘No one’.

4. ‘Populating’ the Place Model

Each of these components can be examined by ‘populating’ Model using the classroom thinking skills technique, Leat’s Living Graphs [

28], to place a range of potential exemplars. The examples also illustrate how the other three logics have a bearing on professions. Using these examples, the following sections provide a tour of the Place Model. The tour begins by initiating the reader into the axis of the model, starting with the top left corner, the ‘proto-professionals’ before making a detour to the off-axis ‘no professional’ component and then moving anticlockwise around each of the three remaining in-axis quadrants of the model, culminating in the ‘professionals’ quadrant. In designing the Model, it has become evident that these components are neither positive nor neutral, that they are mostly dystopian, but, importantly, that there is still, perhaps, a positive place, perhaps even a utopian place for the trustworthy expert.

4.1. Proto-Professionals

The term proto-professionals has been coined here to indicate that this quadrant is often home to professionals at the earliest stages of their careers, for example newly qualified graduates of university courses which are approved by professional bodies. In the present century, these early entrants have been joined by those recruited via less regulated conceptions of professional preparation. This approach has been developed in respect of governments’ attempts to create ‘fast track’ routes for graduates of any discipline, such as Teach First and Step Up to Social Work in the UK, welcoming these entrants as innovators, often in times of personnel shortages, and adjusting (lowering) the required entry standards and competences to ease their way. In the US and in England, for example, graduates may enter the teaching profession via non-university routes to work, often as Zeichner’s

short-term technician teachers,

of other people’s children [

29]

, supported by the view that teaching does not require highly specialized knowledge and skills [

30]. This change in locus of teacher education from the universities to schools has been coupled with the development of more rigidly defined school curricula which may be formulaically ‘delivered’ in a lower tier education system by what Pring calls ‘deliverologists’ [

31]. Giroux contrasts this with the value of an informed and critical professionalism, asserting that there is a danger of teachers “erasing themselves in an uncritical reproduction of received wisdom” (p. 20, [

32]). An even more dystopian view sees the prescribed competences of technicist professionals being, in future, effortlessly ‘delivered’, not by humans, but by AI-controlled robots that continuously learning and do not ever tire – although electronic components may break or become infected with viruses.

Clarke [

14] describes “the most egregious example of ‘training’, as opposed to ‘education’, is perhaps those teachers who are being trained to carry and use concealed weapons in US schools” Alternatively she suggests teachers might be educated (as opposed to trained) “instead seek to combat the systems which produce inequality, poverty and powerlessness for their pupils and hinder their chances of accessing the most elite professions” [

14]. In this context she also mentions “teachers who subvert bureaucracy for their students by giving undue help with coursework/exams (see ‘unprofessionals’) might be seen as a more extreme case of this—in this case, relying on subverting bureaucracy”. Finally she notes, “the proto-professional quadrant may thus be viewed as either an early transit point for some professionals, or as the career-long settlement for others, less ‘well-travelled’ on their learning journey, who remain here because they see this as a comfortable and unchallenging home-for-life, perhaps as a local hero but with few connections and challenges beyond the local”.

4.2. No Place for Professional Nobodies

This component, where the answer to the question, ‘Who is my professional today?’ is ‘No one’, lies outside the axes of the Model. It is, however, indispensable to understanding the place of professionals not least because it poses an increasingly important, existential question for the professions: are professionals a necessity or a luxury, or are they replaceable by either para-professionals or by the ubiquitous, ever-learning potential of AI? For the purposes of this essay, only those who are ‘qualified’ professionals are deemed to be professionals. This point is both fundamental and highly contested, for it is clear that for many professions there may not be national, never mind international, agreement as to the requisite qualifications. This issue presents a significant lacuna not least because it has been the gap though which marketization has sought to break the mold of professions via the increasing deregulation which is mostly occurring in the world’s wealthiest nations. In the poorest places, meanwhile, many millions of people have no access to professionals at all.

This part of the Model resonates with the arguments of those who assert that mandatory qualifications are redolent of credentialism, are inflexible and ultimately superfluous. The growing impact of marketization in recent years has led to a growth of a second tier of para-professional roles; requiring fewer qualifications, greater flexibility and lower costs; temporary jobs attracting lower salaries but increasingly fulfilling some of the roles which were hitherto the responsibility of qualified, permanent professionals. Such jobs are attractive to applicants because the entry tariffs are not as high as those for professions while the role may attract at least some of the esteem of the professions, as the job titles imply: Associate Physician and Teaching Assistant. In addition, there has been an increase in numbers and an extension of the roles of volunteers in public sector roles. In the UK, this has been particularly notable in public libraries where the negative impacts on the erosion of expertise, care of state-funded resources and the quality of service (particularly in poorer areas where long-term volunteers can be harder to recruit) are becoming more evident, as pointed out by the Scottish Libraries and Inflation Council [

33]. Busy professionals may be all too happy to shed some of their more mundane responsibilities to these new minions. The minions, however, may find that they have, for now, undertaken the clearly defined, repetitive types of job roles which are most replaceable by AI. From the perspective of the laity, para-professionals, volunteers and AI may improve access to some services and may even lead to innovation and personalization, but they can eventually create two-tier systems, with the poorest able only to access the services of the least expert and least trustworthy, while the most expert and most trustworthy in any field are available only to the wealthy—exclusive professionals (see below).

UNESCO (the United Nations, Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization) reported on the enormous global disparities in the nature of schools and schooling which mean that 57 million primary school age children lack a teacher [

34]. Lack of teachers has a knock-on impact on all other professions and similarly huge deficits are found in other professions. The World Health Organisation’s (WHO) report,

A universal truth: No health without a workforce [

35], estimated that the world will be short of 12.9 million health-care workers by 2035; today, that figure already stands at 7.2 million.

4.3. Precarious Professionals

The next section moves back within the axes of the Place Model, to the quadrant occupied by the most ‘precarious professionals’ (akin to Standing’s precariat) [

36] who have low esteem, low levels of expertise and/or trustworthiness, and short career spans. This quadrant is home to disparate types including those who might be described as ‘unprofessional’), and those who are unlikely to remain in the profession, the ‘transitory’. Both occupy precarious positions and both frequently reach the headlines—for very different reasons.

Clarke [

14] notes how The Place Model’s unprofessionals pose some key questions for professional educators to ask their students about why and how and by whom they might be registered, access checked and ‘struck off’. Despite these (often inadequate) checks, there are many and varied instances of unprofessional behavior right across the globe, sometimes with fatal consequences. They severely dent the credibility of professionals across a wide range of fields, who may be seen as culpable for the catastrophes while being exclusively protected from the consequences. Acting at their most eponymous, professional bodies often profess codes of accountability, sometimes even encapsulated in professional oaths of conduct, based on the values and competences of their profession, against which such cases are judged. Many of these are locally designed versions of internationally agreed codes such as the Declaration of Geneva for the medical professions [

37]. However, at the heart of these codes there is an increasingly paradoxical lack of candor: despite the increasingly pervasive and distorting effects of the markets, and of performativity measures, none of these codes declare that their profession is ambitious to make as much money as possible, or to subvert bureaucracy and fabricate evidence of competence and achievements, for example. Newly graduated professionals declaring their oaths may sound heartwarmingly virtuous, and no doubt many are genuinely invested in these statements, at the time, but the realities of human frailties and the influence of a marketized and bureaucratized world may soon override such aspirations to virtue. Squaring the circle of duty and ethics is still most glaringly illustrated in the long-standing issues of doctors who assist with carrying out capital punishments. In more recent years, the challenges of ensuring morality within AI are increasing and are, in Katwala’s words, as yet poorly understood [

23].

The other exemplar occupants of this quadrant are the low status, poorly educated professionals for whom job security remains a persistent and stressful problem, where professionals are often badly paid, inadequately supported, and held in such low regard that many are forced to consider other career options. The casualization of contracts is widespread, not least in the academic sector where fee-paying students expect that they are buying access to established rather than ad hoc ‘expertise’. Many of today’s academics are malleable components of flexible labor markets. Many of their predecessors had tenure.

4.4. The De-Professionalized

In creating the Place Model, this quadrant seemed the most interesting and challenging—if it were on an old mariners’ map it might be even be labelled ‘here be dragons’—home to more established professionals who have completed a significant part of their professional learning journey, but with a relative deficit of status.

This quadrant is the locus of at least three contrasting sets of examples: the cynics whose sarcastic words and attitudes can discourage professionals and laity alike, those senior professionals who have been consigned to this place by denigration, including those cast aside following ‘one mistake’, and migrant/refugee professionals who find themselves deemed ‘unqualified’ and unemployable in their destination country.

Members of the first group might be seen, at their worst, to have repositioned themselves within the Place Model. Cynicism can be much simpler than more open-minded skepticism—turning one’s back in vitriolic despair in response to the failed inspection, rather than raising a critical eyebrow and fighting back. McDermott’s paper in this special issue discusses this matter. The senior social workers who worked to try to protect Baby P in the UK are in this quadrant too, but not for reasons of cynicism. When the baby died, the head of Children’s Services at Haringey was ‘named and shamed’ by a senior minister in the House of Commons and removed from post [

38]

. When things go wrong, when mistakes are made, it is often the most senior members of professions who end up being held accountable, sometimes only within the privacy of internal accountability processes, sometimes very publicly indeed with additional vilification via the rabid tabloid press. The further impacts of this case have been on social worker retention and recruitment, on increasing numbers of babies removed from their parents, and on increasing demands for social care at a time of budget cutting austerity. In healthcare contexts, consequences can readily be much more severe; just one mistake can be fatal to patients and also to careers, and the threats of ruinously expensive litigation can encourage coverups. In Northern Ireland’s health service, rules for a

duty of candor are being drawn up following a major public enquiry [

39] and The Doctors’ Association in the UK (DAUK) has introduced a

learn not blame initiative [

40]. There is a growing recognition that much medical fault finding is wasteful and deeply damaging and would be better utilized as a positive learning resource. This can be a difficult message for those harmed and requires the most persistent, eloquent and wise sponsors in order to gain public support.

The problems associated with this quadrant seem destined to expand following statutory increases in the length of teachers’ working lives in most countries. In England and Wales, Sikes (p. 27, [

41]) believes that maintaining professional vigor seems destined to be a particular challenge where the “ageing of members is likely to assume increasing significance for the cultures, ethos and outcomes of schools”.

This quadrant may also be considered to be the locus of those migrant and refugee professionals who find that their previous qualifications and experience count for little in their new state, even though it may have shortages in key fields. In 2017, The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that 68.5 million people around the world have been forced from home [

42]. Among them are nearly 25.4 million refugees and over 80 percent of these are living in economically less developed countries. Perennial arguments around exclusive protectionism in professions versus the wage lowering potential of an influx of new professionals are played out, often

soto voce, in the common-rooms and committees of professional bodies where the challenges of designing and funding appropriate Continuing Professional Development highlight the importance of delineating, maintaining and communicating the profession’s external thresholds and its internal ideals, its distinctive strengths and its singular contribution to the world.

4.5. The Professionals

Thus far, this exploration of professionals using the Place Model has largely pointed towards what an ideal professional

is not, a vision of multiple dystopias which are partly the by-products of professions themselves and sometimes of the impacts of the other logics. By contrast, the Place Model frames the professionals as being progressively expert and trustworthy, highly esteemed exemplars for new entrants to the professions. This quadrant of the Model is home to a profession’s champions, standard bearers, pioneers, leaders and appraisers. Meeting one’s idols is, however, a risky business—as Flaubert [

43] notes, the gold paint tends to come off on your fingers. These super-trustworthy experts are fallible humans too—which can offer the hope that becoming such a hero is, perhaps, an accessible ambition.

4.5.1. Exclusive Professionals

Dystopia is also found even in this quadrant of the Place Model, not least because some of those at the top of professions may be surrounded by boundaries of exclusivity which are patrolled by Cerberus-like personal assistants, by expensive educations which act as what Kynaston and Green call

engines of privilege [

44], by prohibitive fees, by cut-glass accents and expensive tailoring, or, less tangibly, by an assiduously cultivated aura of godlike inapproachability, which may appear just as insurmountable as any physical barrier. These exclusive professionals often live longer and retain exclusive power longer. Professional education tutors might ask their students to consider critically their highest ambitions

: where do they want to go within this most senior quadrant of the Place Model? Seniority is one thing, but they might also be challenged to consider if they intend to serve the rich and powerful, the sophisticated and eloquent, the hygienic and sweet-smelling, while presenting a variety of barriers to others.

The growth of AI has not been deterred by these boundaries. An AI surgeon will have the capacity to assimilate and synthesize all of the case notes of every piece of surgery ever performed, as well as the most intricate details of a specific patient’s medical history, will have the steadiest and most hygienic of ‘hands’, will not tire or become distracted, and may be chosen by a patient in preference to the most eminent of human surgeons. Aggrieved litigants and eagle-eyed managers (often fearing litigation) may seek to ensure that accountability mechanisms are used to remove (professionalize) any surgeon who commits any error. Increasingly, therefore, such exclusive professionals are somewhat less unassailable than they have been to date. Increasingly surrounded, squeezed and encapsulated by the forces of markets, bureaucracy and AI, these top professionals are less likely to rise to their most crucial challenge: using their extensive expertise not to subvert the markets and bureaucracy, not to out-robot robots, but rather to out-human them in curiosity, care and creativity as inclusive professionals.

4.5.2. Inclusive Professional: Utopia or Oxymoron?

Like the exclusive professionals, this final category within the Place Model combines high levels of trustworthiness with the capacity to connect local practice and the latest global expertise. The flaw, however, perhaps the fatal flaw in the notion of inclusive professionals, is that it may be that, as Sandel [

45] comments, in a market society, exclusivity is absolutely essential to professionals in cornering their market, thus making inclusive professions impossible—a utopian oxymoron. Interestingly, Thomas More’s concept of Utopia affords places for both utopias and oxymorons—in the original Greek, utopia may mean either ‘good place’ or ‘no place’ [

46].

The discussion might end here, if it were not for the reality in which many professionals do, in fact, overcome this oxymoron. While inhabiting a world increasingly dominated by markets and bureaucracy, where AI is also more pervasive, less transparent and insufficient in some important human capabilities, many professionals’ expertise and trustworthiness are not for sale, not solely motivated and subverted by ticking boxes, not replaceable by AI. This essay concludes with an attempt to push open the door to a discussion of the possibilities and impossibilities of inclusive professionals.

Most importantly, the place of the inclusive professional might be seen to include the entire map of the Place Model (dystopias and all) which has been created to imagine a more commodious, polysemous understanding of professional. It might be argued that as fallible humans, all professionals have the potential to embody all/many of the components of the model, sometimes several within one day.

Inclusion begins with recruitment into the proto-professional quadrant where most people enter a profession. One hundred percent inclusion is not possible and is only viable at all with the removal of the well documented structural barriers to recruitment: wealth and social class, gender, sexual orientation and race. Realistically, however, professions are still seen as desirable, scarce resources and are thus prey to the perennial sharpening of elbows, (a seemingly incurable, if understandable malaise), starting with the parents of even the youngest school pupils, a phenomenon which is tied to marketization and which, therefore, may be impossible to prevent completely. All professions declare an interest in widening access. Only some succeed to only some extent.

By contrast, the influence of proactively inclusive professionals can be brought to bear right across the Place Model, through the professional bodies which sanction and judiciously (but not wantonly) remove the unprofessionals, in providing mentorship and supporting the learning of peers and proto-professionals, even across national borders in institutional twinning projects or individual one-to-one assistance which aims to supplement or surpass traditional aid projects in the poorest places. Welcoming professions can also reach out within their own localities by seeking to educate the laity about the unvarnished realities their roles:

The Guardian’s ‘

What I’m really thinking’ column [

47], for example, allows practitioners to share candidly the view from their side of the desk/scalpel/book/keyboard/bench. Such pragmatic outreach allows professionals to share in, navigate to (and learn in) places which supersede the constraints of markets and bureaucracy, but may (in reality) be viewed as damaging to the market-cornering potential of professions. This might be further compromized if the professional oaths of inclusive professionals were to explicitly preclude acting on the basis of individual or corporate greed and admit, for example, the reality that even the most extraordinarily talented and dedicated people make mistakes—it is how professionals learn, in response, that matters. The inclusive professional is inarguably a more ambitious outcome of what humanity is capable of than an individualistic survival-of-the-fittest based on markets and constantly monitored and managed by bureaucrats—which might be seen as a pervasive underestimation of humanity. Barack Obama, speaking to

Wired Magazine [

48]

, made an important observation about the future of professionals in the context of more widespread but never fully ubiquitous AI. He predicted that the totem pole of professional status will be upended and that the most human, caring and creative professionals, those who are often underpaid today (teachers, nurses, caregivers, and those in the arts) will, in future, be better understood and more highly esteemed for the universality of their trustworthy expertise.

5. Conclusions

Using the Place Model to reimagine a more commodious understanding of the place of professionals provides a timely and candid analysis which does not lose sight of those who most need the services of the most dependable experts. The Model delivers a useful map of the tensions which exist between the many contrasting viewpoints about who, if anyone, might still be a professional. Those entering the professions must have opportunities to cast a critical eye over their careers, to appreciate that many professionals may be (required to be) increasingly shiny, but are neither expert nor trustworthy, are vilified rather than supported by those in power, and are subject to both marketization of their services and to bureaucratic accountability and also to replacement or augmentation by AI. Likewise, the Model points to ways in which markets and bureaucracy are deforming underestimations of human potential, whist the potential of AI is as yet insufficiently understood. While the competitive markets patrolled by pervasive (and sometime well intentioned) bureaucracy may well be underestimations of the potential of humanity, perhaps inclusive professions are an overestimation. On the other hand, Bourdieu, for all his enduring esteem, has perhaps underestimated the persistent place of professionals as trustworthy experts, particularly in roles involving human qualities which continue to be in demand but cannot be straightforwardly bought, sold, measured or robotized. Such is the place of the inclusive professional, an ideal which (yet) has much to offer to the betterment of the world.