School Development in Culturally Diverse U.S. Schools: Balancing Evidence-Based Policies and Education Values

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Recent US Policy Shifts toward Evidence-Based Innovations and Values

2.2. Traditional Humanistic Values of Democracy and Education

2.3. Culturally Responsive Leadership

3. Description of the Intervention

3.1. Content

3.2. Delivery System

4. Methodology

- How do formal and informal school leaders work in teams to mediate between evidence-based policy requirements at federal, state, and district levels and the needs of culturally diverse students?

- What leadership team practices contribute to school development as measured by improved student outcomes in school letter grades?

- What values from evidence-based policies and democratic education are evident in effective school development?

4.1. Sampling

4.2. Data Collection and Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Quantitative Results

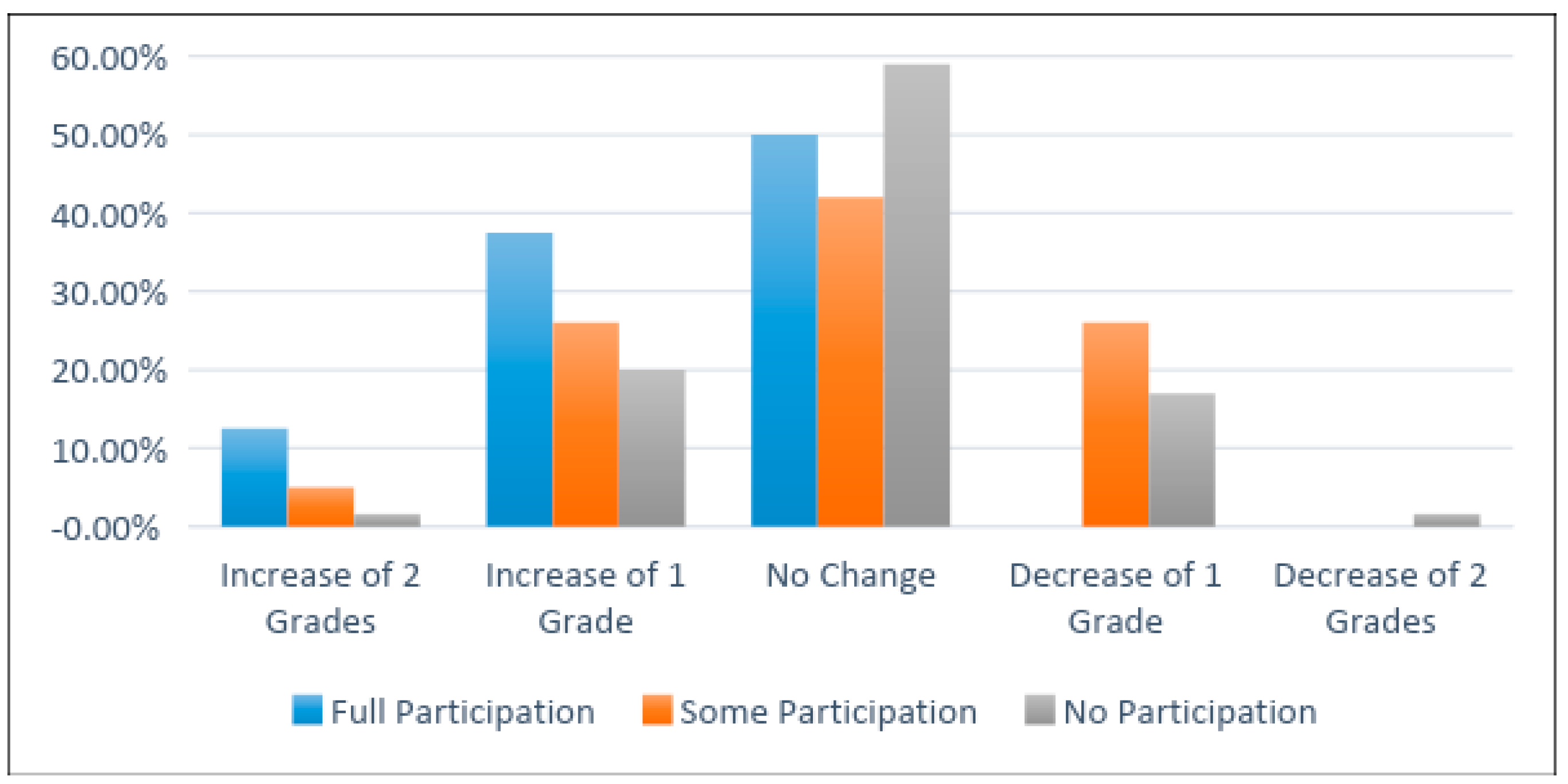

Improved School Letter Grades

5.2. Qualitative Interview Results

You know, I really don’t think we have a real, definite vision. I think right now we were a C-minus school… So I know that is definitely one of his visions, is to get us to improve our C-minus standing. But other than that, I don’t think we all know, okay, definitely what is the vision for the school as a unit, other than moving forward from a C-minus; and that is a big goal.

I know he meets with department chairs, I think it’s once a month, and they meet I think for about an hour. And then their department chairs go back to their department and pass on information that they have gathered from that. So there is—he’s trying to get that communication down. But from there there’s not an avenue, really, to put input back up, so it comes down. And I know I’ve given suggestions to my chair, but I don’t know if it has gotten back up. So there’s no real follow-through on when you have ideas.

Since we started, I have seen changes in the school vision and mission, the directions that we are going in the capacity-building groups that we have, our curriculum action team, as well as the revamped and rejuvenated leadership council with better direction…We have better communication across the board and better professional development for our staff focused on student learning.

[The School Improvement Project] has provided the research, the systems, the applications to start small, look at the low-hanging fruit, start to build momentum, have clarity in purpose and direction, and get the buy-in to start moving forward…it’s showing the principal how to build teams to have, for example, to help with issues on curriculum and culture. It is no longer just the principal trying to lead the way. It’s all encompassing of staff trying to get on board.

I’m still sitting here with my team going, “Okay, we need to do this next year, dah dah dah,” and I have no idea if it’s going to happen or not…I know they’ll carry forward, or hopefully whoever takes over will be open to where we’ve been, and where we were thinking we would be going, and I’m sure they’ll add their own expertise. We want it to be better, and it will be...

We have increased accountability at [our school]…This means we have made our goals and outcomes clearer. We have also further defined individual roles and what they look like so that people can truly be more included and feel their own importance to our shared goals. The further we move along with every individual having clearly defined roles/value/and importance to our team, the more people embrace that and make us more effective as a whole school.

It’s kind of like we’re progressing hand in hand, or what I see this training has enabled us to do is become a team. Before we were every two weeks for 30 min before school. Where we weren’t given time to gel, to use your word, to become a unit. Then what we do, then we take it back to our teams…We went back and we have our thing ready to go.

6. Discussion

7. Limitations

8. Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dewey, J. Democracy and Education; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. The School and Society; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. Experience and Education; Collier Books: New York, NY, USA, 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley, M. (Ed.) Educational Research and Evidence-Based Practice; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie, J. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, B.; Fogelberg-Dahm, M.A.R.I.E.; Wadensten, B. Evidence-based practice: The importance of education and leadership. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavin, R.E. Perspectives on evidence-based research in education—What works? Issues in synthesizing educational program evaluations. Educ. Res. 2008, 37, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. My pedagogic creed. In Curriculum Studies Reader E2; Routledge: London, UK, 1897; pp. 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cain, T. Research utilisation and the struggle for the teacher’s soul: A narrative review. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2016, 39, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordern, J. Knowledge, evidence, and configuration of educational practice. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G.J. Is the team all right? Diversity and teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 2005, 56, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, M.; López, F.A. Leadership for Culturally and Linguistically Responsive Schools; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, K. Causation in Educational Research; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Annual Performance Report (APR) FY 2011. 2012. Available online: http://www2.ed.gov/about/reports/annual/2011report/apr.html (accessed on 12 July 2013).

- Wiseman, A.W. The uses of evidence for educational policymaking: Global contexts and international trends. Rev. Res. Educ. 2010, 34, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhart, M. Hammers and saws for the improvement of educational research. Edu. Theory 2005, 55, 245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, B.; Carnoy, M.; Kilpatrick, J.; Schmidt, W.H.; Shavelson, R.J. Estimating Causal Effects Using Experimental and Observational Design; American Educational & Research Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Slavin, R.E.; Madden, N.A. (Eds.) Success for All: Research and Reform in Elementary Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bussell, H. Choosing a school: The impact of social class on the primary school decision-making process. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2000, 5, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, G.D.; Slavin, R.E.; Cheung, A.C.K.; Chamberlain, A.M.; Madden, N.A.; Chambers, B. Final reading outcomes of the national randomized field trial of success for all. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 44, 701–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, R. Effective schools for the urban poor. Educ. Leadersh. 1979, 37, 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinger, P.; Murphy, J.F. The social context of effective schools. Am. J. Educ. 1986, 94, 328–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkey, S.C.; Smith, M.S. Effective schools: A review. Elem. Sch. J. 1983, 83, 427–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, A. Effective leadership in schools facing challenging contexts. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2002, 22, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lezotte, L. Revolutionary and Evolutionary: The Effective Schools Movement; Effective Schools Products: Okemos, MI, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Granvik Saminathen, M.; Brolin Låftman, S.; Almquist, Y.B.; Modin, B. Effective schools, school segregation, and the link with school achievement. Sch. Effect. Sch. Improv. 2018, 29, 464–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darden/Curry Partnership for Leaders in Education. Available online: https://curry.virginia.edu/faculty-research/centers-labs-projects/research-projects/dardencurry-partnership-leaders-education (accessed on 7 February 2019).

- Harriman, D. University of Virginia School Turnaround Report. Available online: http://www.darden.virginia.edu/web/uploadedFiles/Darden/Darden_Curry_PLE/UVA_School_Turnaround/UVASTSPAnnualReport2008_Excerpts.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2019).

- Calkins, A.; Guenther, W.; Belfore, G.; Lash, D. The Turnaround Challenge; Mass Insight Education and Research Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mass Insight Education. The Turnaround Challenge; Mass Insight Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; Available online: http://www.massinsight.org/stg/research/ (accessed on 16 April 2019).

- Hood, J.; Ahmed-Ullah, N. School Reform Organization Gets Average Grades. Chicago Tribune, 6 February 2012; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G.J.J. Why ‘What Works’ still won’t work: From evidence-based education to value-based education. Stud. Philos. Educ. 2010, 29, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.G.; Castner, D.J.; Schneider, J.L. Democratic Curriculum Leadership: Critical Awareness to Pragmatic Artistry; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ylimaki, R.; Jacobson, S. School leadership practice and preparation: Comparative perspectives on organizational learning (OL), instructional leadership (IL) and culturally responsive practices (CRP). J. Educ. Adm. 2013, 51, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, G. Preparing for culturally responsive teaching. J. Teach. Educ. 2002, 53, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African American Children; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan, M.; López, F. Vamos! How school leaders promote equity and excellence for bilingual students. Educ. Adm. Q. 2012, 48, 583–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandara, P.; Rumberger, R.; Maxwell-Jolly, J.; Callahan, R. English learners in California schools: Unequal resources, ‘unequal outcomes. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2003, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.V.; Ylimaki, R.M.; Dugan, T.M.; Brunderman, L.A. Developing the potential for sustainable improvement in underperforming schools: Capacity building in the socio-cultural dimension. J. Educ. Chang. 2013, 15, 377–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.A.; Riehl, C. What We Know About Successful School Leadership; National College for School Leadership: Nottingham, UK; Laboratory for Student Success: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C. Sustaining success in challenging contexts: Leadership in English schools. J. Educ. Adm. 2005, 43, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.V. “Democratic” collaboration for school turnaround in Southern Arizona. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2012, 26, 442–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, L.C.; Amanti, K.; Neff, D.; González, N. Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Pract. 1992, 31, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, N.; Moll, L.C.; Tenery, M.F.; Rivera, A.; Rendon, P.; Gonzales, R.; Amanti, C. Funds of knowledge for teaching in Latino households. Urban Educ. 1995, 29, 443–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Harris, A.; Strauss, T. Leading School Turnaround: How Successful Leaders Transform Low-Performing Schools; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ylimaki, R.; Bennett, J.; Fan, J.; Villasenor, E. Notions of “success” in Southern Arizona schools: Principal leadership in changing demographic and border contexts. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 2012, 11, 168–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G.J. Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1995, 32, 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Schools Served | 45 | 7 | 19 | |

| # Participants | 80 | 35 | 101 | |

| % School-Rural | 56% | 14% | 53% | |

| % Schools-Urban | 25% | 72% | 37% | |

| % Schools-Suburban | 19% | 14% | 5% | |

| % Community College | - | - | 5% | |

| Ethnicity—Latino/a/Hispanic | Principals | 27% | 58% | 57% |

| Staff | 14% | 32% | 61% | |

| Ethnicity—White | Principals | 60% | 33% | 43% |

| Staff | 60% | 68% | 38% | |

| Ethnicity—Native American | Principals | 11% | 8% | - |

| Staff | 3% | - | 1% | |

| Ethnicity—Other | Principals | 2% | - | - |

| Staff | 23% | - | - | |

| Gender—Female | Principals | 62% | 25% | 75% |

| Staff | 74% | 58% | 88% | |

| Gender—Male | Principals | 38% | 75% | 25% |

| Staff | 26% | 42% | 12% | |

| Principal Tenure— <3 years | 88% | 17% | 29% | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ylimaki, R.; Brunderman, L. School Development in Culturally Diverse U.S. Schools: Balancing Evidence-Based Policies and Education Values. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020084

Ylimaki R, Brunderman L. School Development in Culturally Diverse U.S. Schools: Balancing Evidence-Based Policies and Education Values. Education Sciences. 2019; 9(2):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020084

Chicago/Turabian StyleYlimaki, Rose, and Lynnette Brunderman. 2019. "School Development in Culturally Diverse U.S. Schools: Balancing Evidence-Based Policies and Education Values" Education Sciences 9, no. 2: 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020084

APA StyleYlimaki, R., & Brunderman, L. (2019). School Development in Culturally Diverse U.S. Schools: Balancing Evidence-Based Policies and Education Values. Education Sciences, 9(2), 84. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9020084