1. Introduction

Collegiate athletics is a big business, generating almost a billion dollars in revenue annually [

1,

2]. Today, graduation rates of National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) athletes are on the rise [

3]. The graduation rate has increased in the last fourteen years from 74% in 2002 to 86% in 2016 [

3]. Student-athletes represent a dynamic sub-culture on college campuses due to varying needs and the challenges within their community. Student-athletes, both male and female, are faced with the challenges of balancing academics, athletics, eligibility issues [

4], and associated negative stereotypes, such as being “dumb jocks”, entitled, academically lazy, or only interested in sports [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Athletes also face the pressures of being in the spotlight, which includes media attention and negative criticism [

8]. Other challenges include peer pressure and the high expectations cast upon them from others, such as coaches, parents, and the university community at large [

9]. Additionally, student-athletes endure physical strains on their body, such as injuries and rehabilitation [

9].

Feelings of isolation are common in the athletic community [

4,

8,

9], since most athletes have limited participation and interaction with traditional campus activities and events due to the time demands of their collegiate athletic career [

4,

8,

9]. This isolation limits participation in off-campus internships and study abroad programs, which provide additional training and translate into missed opportunities for the athletic community [

10].

In the midst of these rigorous athletic demands, student-athletes must also make formidable decisions related to career planning [

9], transitioning from college to the workplace [

11], and adjusting to life without competitive sports [

11]. Student-athletes must come to terms with the disappointment of not becoming a professional athlete, and of athletic retirement [

11]. Furthermore, research suggests that athletes who capitalize on their transferable skills have an easier transition to sports retirement [

9]. On average, three percent of all collegiate athletes move onto the professional ranks per year [

3], which indicates the necessity for athletes to capitalize on the curriculum learning and experiential learning at the university level. All of the conversations and decisions above are inherent to the athletic culture and add a layer of stress for these young adults.

Nevertheless, student-athletes gain valuable experiential learning that can prove to be beneficial in the workplace [

12]. Experiential learning is often defined as the practical knowledge and experience gained from engaging in activities outside of the classroom that bridge the gap between curriculum instruction and real-time experiences [

12]. Experiential learning is the focal point of this research study to determine the skills that are transferable to the workplace and the skills employers most desire from student-athletes. The purpose of this study was two-fold and examined from two viewpoints. The first goal was to outline the skills student-athletes obtained through sports participation that are transferable to their current place of employment. The researchers also wanted to ascertain how the transferrable skills were learned through either classroom instruction, experiential learning, or a combination of both. The second goal was to determine which skills prospective employers value the most in student-athletes and how those skills benefit their organizations. This research is necessary because most of the previous literature has focused on the disconnection between career readiness and education preparedness of student-athletes, and the perceived benefit of the experiential learning of student-athletes seem unexplored. There is a plethora of literature on experiential learning gained through practicums, experiential learning curricula, and internships, therefore, this project shifts the focus to the perceived benefits of the learning that takes place through intercollegiate athletics outside of the classroom. Experiential learning helps graduating students meet the changing needs of employers in a competitive market place [

12]. In addition, this project shows that experiential learning occurs through sports participation and an internship or practicum are not the only methods to gain such experience. This article will summarize the theoretical backgrounds, the contextual background, define the methodology, list the results, discuss the results, define the study limitations, list the implications for future research, and wrap up with a conclusion.

2. Theoretical Background

The justification for this study is structured around three theories and is the lens through which the research questions are evaluated. The three frameworks are the Achievement Goal Theory, Kolb’s Learning Cycle Theory, and Signaling Theory.

2.1. Achievement Goal Theory

Achievement Goal Theory is based on the effects a learning environment has on student growth [

13]. More specifically, the theory was designed to understand the obstacles to achievement challenges [

14]. The theory has two major approaches: mastery-centered goals, and performance-centered goals [

13]. Environments that are centered on the mastery approach to education focus on the process to complete a goal, not just the goal itself. Mastery environments are created through the encouragement to identify and learn from personal mistakes, instructor acknowledged improvement, and displaying enjoyment and a connection to work [

15,

16]. The desired outcome in mastery-based environments is competence [

15,

16].

The opposite of mastery goals are performance-based goals. Environments that are centered on the performance approach to education focus on the completion of the goal exclusively. In performance environments, success and failure are measured by the ability to outperform the competition or opponent [

15,

16]. Performance-based environments encourage dominance and are centered on obtaining the best performance using the least amount of effort [

15,

16]. Those in performance- based environments approach tasks based on skills they already have developed and not on how deficits can be improved upon. Therefore, when faced with unmet challenges with already possessed skill-sets, those with performance driven talents will give up or create excuses for lack of success [

15,

17].

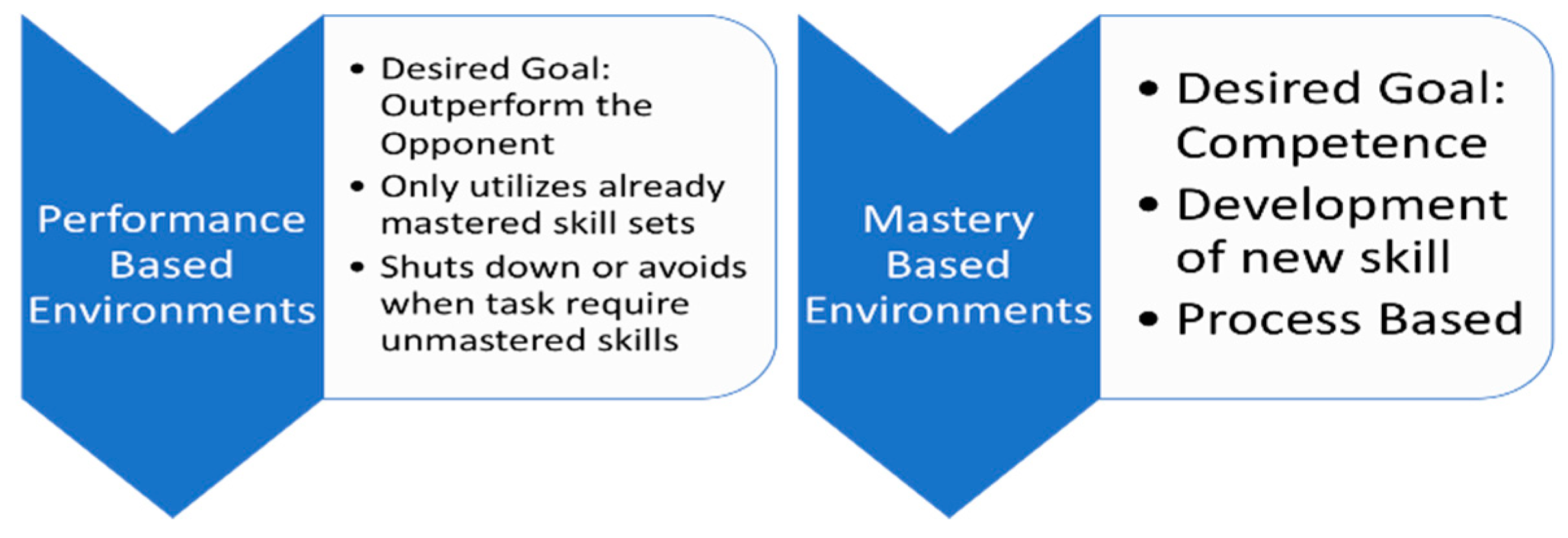

Figure 1 is a graphical summary of the Performance vs. Mastery environments of the Achievement Goal Theory.

2.2. Kolb’s Learning Theory

The second theoretical backdrop for this research project is Kolb’s Learning Theory (KLT), which uses the Kolb Learning Cycle. KLT was developed in 1984, and in summary states that “learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” [

18]. In KLT the actors are cognizant and deliberate in learning from their experiences, which occur over four steps in the Kolb Learning Cycle [

18].

Figure 2 is a graphical representation of the Kolb Learning Cycle.

The Kolb Learning Cycle is classified into four processes. The first phase of learning is experiencing (doing something), the second phase is processing (thinking about what was done), the third phase is generalizing (making meaning of the experience), and the final phase is applying the experience (reflecting, adjusting, and planning for the future) [

18]. During an intercollegiate athletic career, athletes are faced with learning experiences that apply to this theory and allow the individuals to take away valuable learning experiences. Some examples from athletics include sportsmanship, conflict resolution, working with teams, balancing emotions and aggression, time management, and building relationships, among others.

2.3. Signaling Theory

The final theory in this research study is Signaling Theory, which defines how information is shared and received between the athlete and potential employer organizations. The marriage between employee and potential employers uses human capital to gain a competitive advantage in occupational setting. Additionally, the theory is applicable in defining the observation and judgments made by employers on the transferability of skills and values to the workplace. Both parties in this research utilize this theory. Signaling Theory describes behavior between a sender and a receiver [

18]. Signaling Theory also relies on the receiver’s intuition [

18]. The sender—in this case, the student-athlete—must choose the process of communication with the receiver or receivers, which in this scenario are the potential employers. In this dual relationship, the sender decides what to send, and the receiver decides how to interpret the information [

18]. The signaling theory is a familiar concept in human resource management, and is shown in

Figure 3.

During the hiring process of collegiate athletes, the first signals come from the resume when an athlete includes athletic engagement and their athletic accomplishments [

19]. Potential employers then make favorable judgments based on athletic participation, meaning the receiver is observing and interpreting. Research studies suggest that athlete resumes signal to potential employers their potential quality [

19]. In the final stages of the signaling process, the receiver provides feedback to the signaler. Often student-athletes receive favorable responses [

19].

A research study conducted in 2018 compared resumes of athletes without internships to non-athletes with internships, and showed that the reviewers valued student-athletes more favorably, even with the absence of job-related experience Those attributes included leadership, motivation, and interpersonal skills, thus leading the reviewers to make recommendations for interviews. Employers value a well-rounded prospect who demonstrates attributes other than intelligence. Ideally, most marketable athletes will have a combination of athletics, transferable skills, and a direct internship for the best chance at workplace success [

18]. However, in the absence of an internship, the research suggests that the signaling of transferrable skills is impactful and allows athletes to stand out in the pool of potential applicants. Unfortunately, male athletes are given a higher preference over female athletes for their transferable skills, which indicates some gender biases in the employment process, which is not new a new phenomenon [

18].

To develop a further understanding of how the theories apply to the student-athlete population, three research questions and three additional questions were developed to address the employer perspective on student-athletes in the workplace. Together the two sets of research questions and theories formulated our research design and subsequent data analysis.

2.4. Student-Athlete Research Questions

- RQ 1:

What characteristics, values, or skills were learned through sports participation that have helped in the workplace?

- RQ 2:

How were the values and skills learned? Through classroom instruction, experiential learning, or a combination of both?

- RQ 3:

What values or skills were learned from sports participation that have influenced workplace performance?

2.5. Prospective Employer Questions

- RQ 4:

What are the top values, skills, or characteristics required for success in the workplace?

- RQ 5:

Are there skills student-athletes develop in the collegiate experience that make them more attractive hires?

- RQ 6:

Is there a perceived difference in skill sets of athlete and non-athlete employees that give either candidate a competitive advantage in the workplace.

3. Contextual Background of Study

Throughout the college athletic journey, athletic skills are refined through hours of training, practice, and nutrient cycles. Athletes spend countless hours developing their craft and preparing for competition. Some researchers estimate that athletes spend more time on athletic preparation than academic enrichment. According to a study by Traynowicz and colleagues [

16], student-athletes spend over 40 h a week on voluntary and structured activities related to sport, but on average only spend ten to thirteen hours a week studying. Important in this process is the experiential learning that takes place outside of the classroom, which aids the student-athletes development in other areas that add purposeful experiences that shape their identity and prepare them for life after college [

20]; experiential learning and its processes refer back to the Kolb Learning Cycle. The literature review focuses on transferable skills of student-athletes, traditional learning concepts, and the characteristics potential employers’ value. The literature review provides a brief overview of learning methods, and when blended can provide a meaningful relationship between employee and employer that can be beneficial for both parties.

3.1. Student-Athletes’ Transferable Skills

Student-athletes engage in a holistic approach to academia that not only provides traditional classroom instruction but valuable learning and development opportunities through the experiential learning process. Traditional classroom instruction provides opportunities for learning that parallel the experiential learning derived from sports. One example is that many courses employ the concept of team projects to promote the idea of working with others toward a shared vision or common goal [

21]. Dunne and Rawlings [

21] suggest that teamwork allows for an exchange of knowledge and ideas that can prepare students for work after college. Also, teamwork facilitates professional development and encourages partnerships [

21,

22]. Some of the perceived benefits of teamwork include a diverse pool of resources and knowledge and increased participation, with group work promoting self-confidence and allowing team members to engage in discussions that foster innovation [

21,

22]. Another perceived benefit is strengthened interpersonal relationships, and in the university setting group work promotes savings in time, resources, and equipment [

21,

22].

Traditionally, the primary focus of in-class educators has been to teach students how to solve problems and think independently [

19]. To accomplish these goals, many educators teach from an instructor-centered approach. An instructor-centered approach breaks problems into small steps that initially remove learner autonomy while developing a core base of knowledge that gives students a reference point when they do not understand an issue or need to revisit the concept [

19]. Once the baseline level of knowledge is accomplished instructors transfer autonomy to learners and encourage independent thinking and goal setting [

12]. Problem solving and independent thinking has been adopted into the sports world by coaches and has been shown to have a substantial impact on student-athlete motivation and mindset [

15].

Participation in sports provides student-athletes an added benefit of development outside of the classroom [

9]. Transferable skills are necessary to help athletes adjust to life after sport [

23], and include such concepts as problem-solving and concise communication [

22]. Other skills include wellness, social skills development, higher academic achievement, and a greater overall sense of community and belonging within the subculture [

23]. Moreover, sports participation increases leadership skills [

10,

12,

24,

25], improves time management skills [

19,

26], embraces a teamwork ideology [

16], and improves planning skills [

25]. The literature also suggests that peer relationships [

14] and interpersonal skills [

11] develop through sports participation, and is a transferable benefit to the workplace. Student-athletes are also known to be self-confident and goal-oriented [

10] individuals who are of valuable benefit in workplace settings.

However, the literature also suggests that student-athletes do not compare equally to non-athletes because of a mismatch between college majors and actual career interests [

26]. According to Pendergrass and colleagues [

27], only 60% of student-athletes are enrolled in majors they believe will lead to employment. In addition, the strict schedule a student-athlete must adhere to severely limits time for exploration of self through other school-related activities [

27]. However, the skills learned through sports participation are transferable to the workplace regardless of a mismatch [

23]. In summation, the values learned and acquired through sports participation improve “personal characteristics and life skills” [

10] that help prepare student-athletes for life after college [

10]. These acquired skills and values are the top reasons why INC.com and Forbes.com recommend the hiring of student-athletes when building a company with the best employees [

28].

3.2. Characteristics Valued by Potential Employers

In 2012, Enterprise Rent-A-Car (ERC) entered into a partnership with Career Athletes, a resource network of former NCAA student–athletes, to recruit and hire former athletes [

29,

30,

31]. ERC is the official provider to the NCAA and boasts that they are the largest employer of former collegiate athletes. In 2017, a total of 10,000 student-athletes were hired into their management-training program, and another 2000 in their executive leadership program over a five-year period [

29,

30,

31]. Because of the success of the ERC recruiting process, ERC extended their partnership and plans to continue hiring student-athletes [

29,

30,

31] The teamwork culture at ERC is attractive to former athletes and brings the familiarity of the team culture from their sport to the workplace. In addition, ERC benefits from the “athletes’ leadership experience, time management skills, and the ability to work as part of a team translate well to the ERC business and culture” [

29,

30,

31]. The current Executive Vice President and Chief Operation officer of ERC started in the management-training program as a former student-athlete. Christine Taylor was the co-captain of her field hockey team at Miami University in Ohio [

31]

In addition to ERC, Northwestern Mutual has also entered into a partnership with the NCAA, leading to one in five of all their financial representative hires being former student-athletes [

32]. Northwestern’s interest in student-athletes is centered on the connection of characteristics such as a competitive nature, resiliency, self-motivation, and a strong work ethic that are needed in the sales force, and which are developed in sports participation. Since 1967, North Western Mutual has hired over 52,000 financial representatives [

32].

According to literature, there is a set of characteristics that employers value in athletes and employers seek to hire student-athletes over non-athletes because of those unique attributes [

33]. The list is derived from the research of Chaflin group in 2015 [

33]:

- (1)

Student-athletes are employable because they have a competitive nature [

33].

- (2)

Student-athletes work well under pressure [

33].

- (3)

Student-athletes have a strong work ethic and commitment to the task at hand [

33].

- (4)

Student-athletes are confident [

33].

- (5)

Student-athletes have a coachable mentality, which is the ability to take instruction, criticism, and redirection [

3].

- (6)

Student-athletes embrace the concept of teamwork and work well with others [

33].

- (7)

Student-athletes are often self-motivated [

33].

- (8)

Student-athletes are mentally tough [

33].

In 2017, Fred Bastie [

34] wrote an article titled

The Top Six Reasons Why Employers Want to Hire College Athletes, and many of the characteristics from the Chalfin group above are echoed in that writing. Fred Bastsie is the CEO and founder of played.com, which is an industry leader in intercollegiate athlete recruiting. During the recruiting process, Basties’ focus is to align students with the right university by preparing them for life after college and career readiness. The Bastie list is as follows. Collegiate athletes are goal oriented, which is shown through years of commitment to their athletic endeavors [

34]. Collegiate athletes are mentally tough, resilient, and participate 100 percent, even on days when they do not feel up to their best performance [

34]. Collegiate athletes are hard workers, great time managers, and can multitask [

34]. Collegiate athletes are self-confident [

34]. Collegiate athletes are good teammates who can work with a group of people toward a common goal [

34]. Collegiate athletes tend to be leaders [

34]. All of these characteristics are valuable to organizations.

David Lavelle, CEO and Co-Founder of Gameface Medica Inc., wrote an article titled

The Traits of Athletes That Can Predict Workplace Success in 2015. Lavelle’s viewpoint is that his company goes above and beyond to hire student-athletes because “the negative stereotypes surrounding athletes are misleading” [

5]. The author further writes that his company is attracted to student-athletes because student-athletes have a great work ethic, can overcome failure, display positive energy, and have the ability to handle risk and responsibility [

35].

A contributing author for Inc. Magazine wrote an article titled

7 Reasons Athletes Make the Best Employees [

36]. The list of characteristics includes some of the same traits previously written. However, DeMarais lists traits previously unmentioned. Those traits are summarized as follows. Student-athletes are trained to practice until perfect and bring that same desire to improve into the workplace. Student-athletes are accountable for their actions, and they understand their role within the team [

36]. Additionally, athletes can handle criticism, process the feedback, and ultimately take corrective measures [

36]. The examples provided show that employers’ value characteristics in athletes gained through participation in sports. While steeped in competition, the rigorous combination of coursework and sports prepare athletes for success in the workplace. These experiences are learned under the framework of the Kolb Learning Cycle, which states that learning occurs through the process of experiences.

4. Methodology

Framing this study is a mixed-method approach to gathering the data. Two questionnaires were designed for distribution to student-athletes and potential employers. The questions in the surveys were crafted based on the literature review. Based on the literature, athletes gain experience in teamwork, professional development, setting and achieving goals, building interpersonal relationships, communication, and developing leadership skills. In addition, athletes learn how to be accountable for their actions, they learn lessons in critical thinking and problem solving, along with developing self-confidence; all of these attributes are refined through athletics. Both of the surveys in this study went through a series of field tests prior to launching to ensure the questions were understandable, were not leading, and would produce useful data that answered the research questions. The student-athlete survey is titled Student-Athlete Workplace Preparedness and is located in

Appendix A. The employer survey is titled Questionnaire for Potential Employer Data Collection and is located in

Appendix B The field test participants included two human resource professionals with direct hiring responsibilities, two former NCAA student-athletes, and two business owners, one of whom is an expert in survey construction and corporate research. Through these in-depth analyses, revisions to the surveys were made for clarity and weak and irrelevant questions were removed.

Table 1 below identifies the connection between the research questions and the survey questions.

The questionnaires allowed for both quantitative and qualitative responses, which allowed the researchers to retrieve data that included responses based upon the literature review and an added layer of in-depth personal experiences and reflections. The questionnaires used a combination of forced choice questions, multiple select questions, and short open-ended questions to address the research questions. By using a combination of quantitative and qualitative data, the researchers were able to extract meaningful data that reflects the participant pools personal experiences. The data provided the descriptive data necessary to outline the importance of experiential learning, the relevance of transferable skills, and the value student-athletes add to organizations.

4.1. Description of Sample Student-Athletes and Employers

The goal of the student-athlete survey was to have 100 completed surveys from the participants; 89 participants opened and started the survey, with a total of 61 completed submissions (n = 61) during the research period. The completion rate was 69% and there were 28 dropouts midway through the survey. The demographics of the participant pool shows a diverse group of participants by gender, age, years on the current job, the sport played, NCAA Division, and highest degree earned.

Table 2 is a representation of the participant’s demographics, including the category, number of responses, and percentage of the overall responses.

The participant pool included 47 males and 25 females—the most popular age range was the 25–34-year-old sector. Thirteen sport classifications are included, and the most significant percentage of respondents was from the football player category (32.91%), and data was obtained from all three NCAA divisions. The majority of the participants (87.5%) have at least a bachelor’s degree. Less than 5% of the participant pool did not receive a four-year college degree. Other data showed that the majority of the participants (76.67%) attended school in Pennsylvania; however, nine other states are represented in the participant pool.

Table 3 is a listing of the states represented along with number of respondents and the percentage of the overall group.

The participants in the survey represent a wide variety of occupations. The largest category of participants work in athletics (25%), which includes high school and collegiate athletic departments as athletic directories, athletics administrators, compliance directors, or coaches. The data suggests that former NCAA athletes continue to feed their passion for sports by continuing careers in sports. The second largest category, with 20% participation, was in the business management category, which includes positions such as branch managers, project managers, human resource managers, compliance managers, and safety managers, to name a few. The participant pool includes a Grammy-winning record producer, a pharmacist, business owners, an engineer, and employees in the medical field. The careers and occupations of the pool show a variety of occupations of former NCAA student-athletes.

Table 4 is a listing of the job categories of the participants, the number of responses, and the percentage of the total pool.

The goal of the employer survey was to have 50 completed surveys from the participants; 53 participants opened and started the survey, with a total of 37 completed submission (n = 37) during the research period. The completion rate was 70% and the survey had 16 dropouts midway through the survey. The demographics of the employer pool show a diverse group of employers by gender, age, collegiate sports participation, and years on the current job.

Table 5 is a representation of the participants’ demographics, including the category, number of responses, and percentage of the overall responses.

The employer pool includes more males than females, and the most popular age range is the 25–34-year-old sector. The majority of the participants (48.65%) have been at their current job for over 11 years. Roughly 60% of the participant pool did not participate in collegiate sports. Other data showed that the majority of the participants’ businesses were located in Pennsylvania (89.19%); however, there were three other states in the participant pool. Fourteen possible employer classifications are included, and the most significant percentage of respondents came from employers in the “Business and Professional Service Sector” (27.78%). A breakdown of the industry representation is below in

Table 6.

4.2. Data Collection

The survey period for the former athletes began on February 20, 2019, and concluded on March 9, 2019. The participants are from groups such as Facebook, LinkedIn, Western Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic League (WPIAL), a semi-pro football team, and a WPIAL Referee board. A link to the survey was posted to the personal Facebook pages of the researchers, and within sports-related communities on Facebook and LinkedIn. The survey period for the employer survey began on March 1, 2019, and concluded on March 14, 2019. The employer participants were generated from Facebook and the Eastern Minority Supplier Development Council (EMSDC). The EMSDC is a subchapter of the National Minority Supplier Council, which promotes diversity and inclusion for minority business owners in the corporate sector. An email link was sent to the local Western PA page of the 100 Black Men of Western Pennsylvania. Weekly email reminders and social media posts helped to generate additional responses. The surveys were designed to allow only one response per IP address to avoid an over-inflation of the data. The quantitative data was evaluated to obtain descriptive statistics and to compare subgroups. The open-ended questions were analyzed to find common themes in the data.

4.3. Ethical Considerations

Before the data collection process began, the researchers obtained Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval from Robert Morris University. IRB is the approval process whereby the researchers obtained approval from the universities committee to ensure the proposed research, methodology, data collection procedures, risk to benefit analysis, and data storage procedures abide by the ethical standards of the university. All participants were assured of their confidentiality and advised that their participation was voluntary. Voluntary participation was the act of granting consent. Participants had the option to exit the survey at any time, and no personal information of the participants was collected. The research was carried out upholding the ethical guidelines of the University.

4.4. Data Analysis

The quantitative data was analyzed for descriptive statistics of the population, including the number of responses and the percentages of the overall group. In some instances, counts were analyzed to determine the strength of the responses. No other statistical analysis was performed between the sub groups of age, sport, NCAA division, or profession, because an overwhelming majority of the participants shared similar responses. The qualitative data was analyzed for common themes and coded using the five-step process outlined by O’Connor and Gibson [

37].

Step one is the organization of all the data into one centralized location. This step was essential to ensure all information needed to answer each of the research questions was combined and separated from information that was not needed.

Step two is the finding and organizing of ideas and concepts. In this step the researchers examined the data for consistency and language and began to establish themes.

Step three is the building of overarching themes in the data; the establishment of themes helped the researchers condense similar ideas under one main idea.

Step four is the ensuring of reliability and validity in the data and the analysis of the findings. In this study, data was reviewed independently by both researchers, and then compared for analysis before the themes were finalized.

Step five is the findings and possible and plausible explanations of the findings. In this step, the researchers summarized their findings and examined them for consistencies and outliers in comparison to current literature.

5. Results

The results defined in this section are derived from the student-athletes and the perspective employers. The results discuss the common values and characteristics developed through sports participation, the attributed learning methods, and the transferrable learning through sports that impacts the workplace. Other results include the skills employers’ value the most. Collectively the results show that transferable learning exists and employers’ value those skills learned during that process.

Using a multi-select question, participants had to identify common values or characteristics identified in the literature review that were developed or learned through sports participation. There was a total of 502 responses to the question (n = 502). The possible number of responses per value is a maximum of 61, which is the total number of completed surveys. The top values learned through sports, according to the athletes, included teamwork and collaboration (93%), commitment (92%), leadership (85%), time management (82%), and perseverance (75%). Teamwork [

5,

10,

33], leadership [

4,

11,

22,

33], and time management [

11,

22] are all skills highlighted in the literature review as transferable skills through experiential learning.

Table 7 lists the values learned through sports in rank order.

The former athletes identified how they learned the characteristics through either sports, classroom instruction, or a combination of both. The data showed that the top three values learned through sports are learned through a combination of classroom instruction and athletic participation.

Table 8 is a representation of the learning methods, the number of participants, and the overall percentage (n = 61).

The table shows that conflict resolution (72.9%) and leadership (63.9%) are two of the values learned the most through sports. All of the other characteristics are learned through a combination of sports participation and classroom instruction. No matter the split of the learning method percentage, the data replicated the literature review and showed that learning takes place through sports participation and classroom instruction. In addition, the qualitative responses show that an overwhelming majority of the participants listed building relationships, networking, and diversity as characteristics learned through sports participation. One respondent writes, “Building relationships with individuals that you may not see eye to eye with, however, you have to find a way to work toward a common goal as a team that goes far in the workplace.” Another response states, “The biggest lesson I’ve learned is how to deal with people and varying personalities. Being on a sports team gives you the opportunity to interact closely with a varied group of people with a common shared goal; however, there are different methods of accomplishing that goal, which is very similar to the workplace setting.” The results are synonymous with the literature review—building and creating interpersonal relationship are skills that are transferrable to the workplace through experiential learning [

4,

10,

11].

Using a forced-choice option, the participants had to agree or disagree with statements that evaluate transferrable learning skills to the workplace. For each of the statements n = 61, and most of the statements have a 92% agreement rate or higher, except for conflict management. The characteristics with at least a 92% agreement rate include managing interpersonal relationships [

4], [

11], managing conflict [

23], time management [

11,

22], leadership skills [

4,

11,

22,

34], teamwork [

8,

10,

34], and adaptation to specific roles.

Table 9 is a complete breakdown of the statements evaluated and the percentages of agreement and disagreement.

In a similarly structured survey, 37 employers from various fields ranked the importance of specific workplace skills, using a scale of one to five. A score of five indicates the highest degree of relevance. These skills were selected strategically based on the top skills athletes gain from sports participation discovered in the literature review. The results showed that all of the top ranked skills developed associated with sports participation are highly valued in all work sectors, with integrity and attitude, teamwork, commitment, and accountability rounding out the top four values.

Table 10 is a listing of the employer values in the workplace, and each value is listed in order of their scores

The second portion of the employer survey consisted of ten statements. Participants were asked to choose whether they agreed, disagreed, or were indifferent towards each statement. The human resource managers and business owners on the survey agree (83.79%) that a large portion of collegiate learning happens outside of the classroom and 94.59% of the potential employers agree that multitasking is a necessary skill for workplace success. The remainder of the results varies and shows a wide variety of indifference between student-athletes and non-student-athletes in the workplace. The complete list of results is listed below in

Table 11.

The final section of the employer survey focused on workplace beliefs between former collegiate student-athletes and non-athletes. Give a list of seven statements, the employers selected who fits each statement the best. The choice options were student-athletes, non-student-athletes, or both. If a particular characteristic was not believed by the employer to be present in their work place they could also reply “N/A” for not applicable. According to the results, the student-athletes are superior to non-athletes in fast-paced work environments, putting forth the most effort, taking accountability for their actions, and having a better transition to the workplace. The complete set of results are below in

Table 12.

6. Discussion

The literature review showed that a vital component in transferrable skills of student-athletes is the idea of teamwork and collaboration. The athletes in the survey echoed those sentiments, with 97% of the participants agreeing that teamwork is a lesson learned through sport and traditional classroom learning. In order to have a cohesive team culture, the members of the team must subscribe to a shared vision, shared goals, and strive to achieve those common goals. A competitive team setting is no different from teams in the workplace. Athletes enter into a workplace with the concept of teamwork and roles embedded into their persona; 100% of the participant pool agreed that a valuable lesson learned from athletics is teamwork and adapting to specific roles. A component of teamwork is building relationships to foster an exchange of ideas, stimulate innovation, and share knowledge along with resources. A total of 97% of the respondents agreed that the values and lessons learned from sports participation improved their work performance.

The respondents were candid in their response to what they learned outside of the classroom through sports that most prepared them for the workplace, and many of the responses focused on teamwork, building relationships, and interactions with people. One participant wrote, “Teamwork, accountability, work ethic, and relationship building” is what was learned outside of the classroom. Another replied, “I was a much more confident person because I was an athlete. Talking to people was easier and handling tough situations were easier because I had already been in numerous tough competitions in college.” Another respondent specially addressed people and relationships, “Learning how to deal with people in a public or work environment” is what sports taught them the most. Finally, one respondent said it best, “I learned a we versus me mentality by playing sports.” Evident through this study are the transferrable characteristics of teamwork and collaboration, which provide a completive advantage in the workplace for NCAA former athletes.

The literature review suggests that sports participation increases leadership skills in student-athletes, and according to this survey 64% of the participant’s state leadership is most learned through sports participation, and 34% feel the leadership is learned through both methods—classroom and sport. However, when asked to define their greatest takeaway from sports, many of the participants responded with many leadership attributes. The statements included accepting differences, which translate into diversity and inclusion, the ability to communicate, which is a vital component of leadership, and realizing that others depend on the former athletes, which translates into accountability. Other statements from the participants included expressions about conflict resolution, having patience, the ability to multi-task, along with time management and committing to the set goals. Leadership involves taking risks, handling adversity, and giving and accepting constructive criticism.

The collection of athletes in this survey show true leadership through their responses and the job positions in which they hold. Over 60% of the participants are in executive leadership positions. The data lends credibility to the idea that athletes ascend the ranks in organizations, public or private. Also, athletes learn valuable skills and lessons through sports that enable career advancement because student-athletes are competitive in nature, which makes them strive to “be the best,” “strive for the top,” and “never fail”, as stated by the participants of this research.

The employer survey examined the transferable skills learned through sports participation and the transferability to the workplace. The findings in the literature review show a plethora of skills that develop during sports participation and are transferable to the workplace [

9]. Using the findings as a starting point, the researchers created a list of the top transferrable features obtained through sports participation. All twelve of the utilized features are listed in

Table 9. Each feature was ranked as extremely important by all employers and across all fields in this study. The findings in

Table 9 were consistent with the articles written by Bastie [

3], DesMarais [

9], and the Chalfin group [

5].

Table 10 displayed the beliefs surrounding the establishment of skills through sports participation from the perspective of employers. The section of the survey that gathered the data for

Table 10 asked employers to answer questions that identified whether they agreed, disagreed, or were indifferent towards statements about student-athletes. Overall there was only one area in which the employers did not agree with the provided statement. More employers disagreed on the fact that they noticed a difference in work place effort between former student-athlete employees and traditional employees. However, this statement was contradicted in the last section of the survey on employer workplace beliefs, discussed below.

Similar to the findings of the Chaflin group [

34], across all fronts employers believe student- athletes hold more favorable characteristics that are beneficial in the workplace in comparison to non- athletes. Results showed a belief that student-athletes perform better at workplace tasks than their non-athlete counterparts. The greatest difference between athletes and non-athletes surrounding employer work place beliefs were “putting forth the most effort” and “responds to constructive criticism”. DesMarais [

37] and Bastie [

36] showed that, as well as the idea of employers favoring student-athletes in the workplace over non-athletes, even non-athletes who held internship experience mentioned both of these key characteristics in job preparation articles.

7. Study Limitations and Implications for Future Research

While this study is worthwhile and highlights the relevance of a holistic approach to academia, the researches acknowledge that there are limitations to the study. The participant pool of student-athletes and employers is not representative of all sports, is not inclusive of all athletes, or a representation of all classifications of employers. In addition, this study is limited geographically—the vast majority of participants, athletes, and employers are from the Pennsylvania area, limiting the geographic range of this study. The level of experiential learning is unmeasurable, and since a formal evaluation system is not in place, we can only assume that experiential learning has taken place based upon the expressions of the participants. In terms of employers’ evaluation of student-athlete workers versus non-athlete employees, the study does not account for the duration of experience accrued in the workforce from the current employer or other companies, since some learning may have occurred in other workplaces. The participant pool of student-athletes does not seem to identify an equal representation of student-athletes who failed to finish college or had an unsuccessful time gaining employment; therefore, the groups targeted for student-athletes seem to favor those with successful student-athlete stories. Finally, on the employer survey, this study is limited to the employers’ experiences working with student-athletes, and the employer survey did not eliminate employer participants who had not hired or were not aware they hired student-athletes in the past. Therefore, some employers’ answers could be based on perception and not actual experience.

To strengthen the ideology that transferrable learning from athletics is a useful form of academia that gives student-athletes a competitive advantage, future studies are necessary. An in-depth qualitative comparative case study analysis of student-athletes and non-athletes of identical majors during the post-graduation and job searching segment of their lives could contribute usable data to this field of study. The study can determine if there are differences in employability, level of progression (career advancement), job transfer rate (layoffs or terminations), employer and employee satisfaction rates, and how the experiential learning impacts workplace performance between the two groups. Additional studies are necessary to help student-athletes, employers, athletic leaders, and academic professionals recognize that transferable skills exist, how to build upon those skills in the athletic study body through curriculum, how to measure those skills, and how to adapt the usefulness of transferrable skills to the workforce. Acknowledging that transferrable skills exist is not enough. Continual research is necessary to build the body of literature in this field of study to provide meaningful data to strengthen the concept that experiential learning is a value-added commodity to student-athletes and influences the workplace for student-athletes.

8. Conclusions

According to the athletes who participated in this research, the top five values learned through participation in sports include teamwork, commitment, leadership, time management, and perseverance. When the employers were given the opportunity to rank the characteristics, on a scale of 1 to 5, on value in the workplace teamwork (4.68), commitment (4.59), and time management (4.49) were ranked high on the employers list. The data suggests that the student-athletes improve characteristics learned through sport participation that are highly valued in the workplace.

The two characteristics learned the most through sports participation, according to the athletes, are conflict resolution (72.9%) and leadership (63.7%). Although conflict resolution does not appear to be a common value or a highly regarded trait, the job positions or careers of the participants suggest that conflict resolution and leadership are necessary skills. Included in the participant pool are 12 executive managers and five chief executive officers—both of these positions require the ability to lead a team of people and resolve internal and external inflicts. The participants working in athletics (15) included athletic directors, compliance directors, and coaches—those positions also require leadership and the ability to resolve problems or issues. Several of the other occupations have some degree of leadership and a conflict resolution element; those positions include an engineer, a lawyer, higher education positions, and social work. The refinement of their leadership skills and conflict resolution skills can be attributed to sports participation, according to the athletes.

The teamwork atmosphere of sports promotes the idea of learning how to work well with others and how to build interpersonal relationships; in the process of building interpersonal relationships they learn how to make adaptations to those around them. The survey results show that 95% of the participants agree that sports participation helped them to manage interpersonal relationships, and 92% of the participants agree that managing interpersonal relationships is a vital job function in their workplace. From the careers listed by the student-athletes, most of them work in a team setting and interact with other people on a daily basis.

The employers who had hired or had experience working with student-athletes consistently rank the athletes more favorably than the non-athletes in the following categories: handling work place conflict, responds to constructive criticism, works well in fast paced environment, puts forth the most effort, takes accountability for their actions, and has a better transition to the workplace. Although these attributes are not necessarily transferrable learning skills, they are attractive qualities in student-athletes that can give them a competitive advantage over non-athletes in the workplace.

The participants in this study excelled in the classroom as well—thirty-seven percent of the athlete participants obtained masters degrees, and eight percent obtained a doctoral degree. When evaluating the totality of the participants, an employer responded that one can ascertain that student-athletes are a committed group of people with a sense of commitment to their endeavors, which can translate to upward mobility in the workplace and prove to be an asset to the organizations in which the athletes serve. Therefore, the transferrable learning that takes place through sports participation is a valuable commodity in the academic process. Learning occurs through various methods and transferrable knowledge through lived experiences is vital to the education process of student- athletes. Student-athletes are subjected to stereotyping of their academic abilities, praise for their athletic ability, and isolated because of the athletic culture. Yet, athletes learn valuable skills through athletics that are transferrable to the workplace post-graduation and helps student-athletes excel in their careers. Teamwork, leadership, communication skills, problem solving skills, and perseverance are attractive qualities in student-athletes that allow them to flourish in the workplace. The values and characteristics learned through sports participation has helped the athletes in this study ascend the ranks of their organizations, aspire to be leaders within their organizations, created the drive for graduate degrees, and to become entrepreneurs—this is evident from the participants’ responses.