1. Introduction

A great number of innovations emerge day-to-day within digital technologies, including internet technologies or mobile technologies. In particular, with internet technologies, there are a lot of web-based sites or applications that stick in our daily life and enable individuals to reach different goals. The widespread use of the internet personally in education, health, business, and the private sectors draws the attention. Individuals use the internet with many different purposes, such as using social networks, forming identities, signing up a group, reading the news, expressing opinions, listening to music, watching videos, and so on. Furthermore, user-generated content sharing, through social media networks is an undeniable fact of everyday life with the development of digital technologies. Therefore, the mass media, popular culture, and digital technologies shape individuals’ attitudes, behaviours, and values throughout their lives. The widespread use of mobile communication and the use of the internet for interactions between objects (internet of things, [

1]), rather than just the means of interaction between individuals, indicates the importance of raising awareness about digital skills. At this point, there is great importance of educating individuals who are well aware of digital media environments, who take critical and effective decisions, as of changes in medium, consumer/individual, and in the forms of communication.

Digital literacy, which is also conceptualized as “new media literacy or digital media literacy” [

2], today, is of great importance in terms of using digital media in competent forms, as well as understanding paradigm shifts in learning settings. In a broader sense, digital literacy is to be able to access the accurate information in authentic and virtual environments, with the desired purpose, and use it efficiently with the right method. That is, it is the ability to find, organize, understand, evaluate, and analyze information using digital technologies and the ability to understand and use existing advanced technology [

3]. Especially along with the social networking sites, the emergence of a participatory culture has been the most fundamental determinant of digital media environments, with becoming a productive dimension rather than following the information in the Web2.0 environments. Considering the definition of digital literacy, the use of digital media by individuals and society, interpreting, sharing, collaborating, evaluating critically, and exhibiting skills that are required to create digital media content, and to implement social responsibilities and ethical principles, can be competences of digital literacy. Individuals who have the ability to become literate in digital media are expected to have the basic knowledge about self-contained skills, such as privacy, freedom of expression, internet law, information production and management mainly, as well as the ownership structure of digital media environments and the language and concepts of digital media [

4]. Similarly, the basic competencies of digital and media literacy were categorized into five groups: Action, Access, Analysis and Evaluation, Creation, and Reflection [

5].

On the other hand, such dissemination of content production, which is a result of the participation and interactivity provided by digital media technologies, led to an increase in information and causes problems, such as dis-information and information obesity [

6]. Ethical and moral codes as principles to be known and observed in digital media offer a basic knowledge of literacy at the same time. The fact that cyber space is so intrinsically intertwined with actual life brings important problems, such as violation of ethics/moral codes. In addition, the closure of the ‘digital divide,’ that emerges in the relevant literature as a reflection of individual and community life with digital technologies, is also feasible with digital literacy. This is because the step of closing the digital gap requires access to communication technologies and the other requires having heightened digital skills regarding using these digital technologies. Along with the widespread use of the internet, the concept of “digital fluency” [

7] emerges as the ability to reach a certain level of competence in using internet tools, to critically evaluate the content, question the validity and reliability of the content, and to be aware of the diversity of users and technology. The rapid developments in digital technologies also led to the fact that the digital literacy phenomenon is constantly being updated. In a broad sense, if these skills were not gained by individuals, digital technologies may affect social change negatively. On the basis of all these evaluations, digital literacy, especially defined through social media platforms, is not limited to reading, consuming and interpreting digital media messages consciously, critically, and analytically. Individuals are also required to invest in effective digital media management and producing qualified content. In this regard digital literacy is also necessary to sustain a participatory and liberating spirit with digital technologies.

Today, digital literacy plays an important role in participating in society as a citizen. The fact that, not only social life, but also economic, political, and cultural life is revealed through digital media, increases the importance of literacy. The construction of a healthy society in which new digital technologies dominate naturally requires digital literacy. At this point educators are pioneers in the up-bringing of future generations. Including them within society as individuals, with high levels of awareness, and improving their democratic and contemporary perspectives is significant. Teacher-related classroom practices appear to make a significant difference to individuals gaining awareness in respect of digital technologies. It would be contended that this is particularly related to teacher quality, such as the degree to which teachers are aware of digital technologies and related skills, the extent to which teachers have sufficient knowledge in digital technologies, their beliefs on the use of digital technologies in the classrooms, and instructional practices relevant to digital technologies in their classrooms, and so on. Many researches have also extensively documented that, when digital technologies and new literacy skills are integrated into curricula, significant and positive learning outcomes emerge in learning settings (e.g., [

8,

9,

10]). There is a need for well-educated and well-equipped educators in digital literacy, in order to achieve all of these.

Rationale of the Study

Although scholars who are interested in digital technologies and new literacy studies have particularly stressed the importance of using the potential of literacy practices supported with electronic environments (see, e.g., [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]), there is a growing gap between required classroom practices in the 21st century and teachers’ use of digital technologies. One of the problems is rooted in teacher attitudes towards the use of digital technologies and having the necessary active teaching strategies. It is believed that, at the core of effective integration of digital technologies in teaching and learning lie capacities, which go beyond mere access and digital literacies. It has been quite late in the formation of the awareness of the importance of digital literacy in educational institutions [

16], and there are limited numbers of studies examining digital literacy issues in Turkey. Although, there seems to be various reforms in primary and secondary education programs, it is noteworthy that no significant regulations are made in teacher education programs in Turkey. Eventually teacher education programs were revised by the Council of Higher Education in 2018 in Turkey. The media literacy course is an elective course in almost all programs. The course covers topics, such as information literacy, the conscious use of internet and social media, the effects of social media on individuals, the power of information dissemination and misleading media, the media and perception management, legal rights and responsibilities for the media and the internet, copyright, violation of privacy, popular culture, gender roles in media, consumption culture and advertisements, stereotyping in the media and so on [

17]. In fact, pre-service teachers, that would play an important role in educating individuals who will have a say in the future of the country are expected to be well-equipped with digital literacy skills. Therefore, the necessity of being digitally literate in pre-service teachers is very obvious. With this overall purpose, the following questions were addressed:

- Q1.

What are the digital literacy levels of pre-service teachers?

- Q2.

What perceptions do pre-service teachers have about digital literacy?

- Q3.

Do pre-service teachers’ digital literacy perceptions vary by their demographics?

- Q4.

To what extent are the quantitative results on pre-service teachers’ digital literacy perceptions in line with the pre-service teachers’ views of factors affecting the development of digital literacy skills?

3. Results

The mean and standard deviation scores of the perceptions of pre-service teachers on the measure of digital literacy are presented in

Table 2.

Given the mean scores of the pre-service teachers’ perceptions on the measure of digital literacy in terms of the whole scale and its dimensions, the pre-service teachers had high and positive perceptions of digital literacy, indicating more confidence in using digital literacy skills. Participants also indicated their understanding of the concept of the digital literacy with expressions, such as “keeping step with innovations”, “process of accessing information”, “use of technological tools”, “finding, verifying and sharing information”, “using digital media effectively”, “using the internet effectively”, “writing and reading programming languages such as C, C++, Java,” and “using the technology at the right place and at the right time” in interviews. See

Table 3.

Based on

Table 3, there was a statistical significant difference the female and male preservice teachers’ digital literacy perceptions in favour of the male pre-service teachers (

t (293) = −2.083,

p = 0.038). Although the majority of participants in the interviews indicated that gender does not matter in this case, some excerpts regarding the extent to which being a male or a woman make a difference in the digital literacy perceptions or beliefs provide as follows:

Participant 3: Men are more interested in various educational branches such as computer engineering and information systems engineering, and as a result, males are at forefront on this manner. However, it is possible to say that women appear to be more active in social networking.

Participants 42: Considering that men are a bit more interested in digital devices, I think men are bit more qualified than women in this regard.

Participant 35: I think that this situation’s changes are not to do with the concept of gender but with personal and social differences.

Participants’ opinions regarding the extent to which being a male or female make a difference in their perceptions or beliefs are given in

Table 4.

As seen in

Table 4, of the participants, 32 (64%) indicated that gender difference does not matter in perceptions of digital literacy skills. In addition, 10 (20%) participants indicated that personal interest and desire is a factor rather than gender. Three (6%) pointed out that males are expected to be more aware more on digital literacy as they are more interested in digital areas and digital tools. Similarly, 3 (6%) stated that cultural and social customs play a role in individuals’ digital literacy perceptions and skills. Lastly, 2 (4%) pointed out that females are more aware of digital literacy concepts as they are more coconscious. The findings, showing whether there are statistically significant differences among the majors of the preservice teachers considering their digital literacy perceptions, are presented in

Table 5.

Considering

Table 5, one-way analysis of variance showed that the pre-service teachers digital literacy perceptions differentiated significantly by their majors (

F (7227) = 3.549,

p = 0.001). Post-hoc multiple comparisons, using the Tukey HSD test indicated that the mean score for pre-service teachers majoring in science (

M = 4.04, S

D = 0.54) was significantly different than pre-service teachers majoring in mathematics (

M = 3.48,

SD = 0.50), the pre-service teachers majoring in social studies (

M = 3.47,

SD = 0.85), and the pre-service teachers majoring in psychological counselling and guidance (

M = 3.53,

SD = 0.68). The findings, showing whether there are statistically significant differences among the age of pre-service teachers based on their digital literacy perceptions, are presented in

Table 6.

One-way analysis of variance showed that the pre-service teachers’ digital literacy perceptions did not differentiate significantly by their age (

F (4,290) = 2.213,

p = 0.068). The findings, showing whether there are statistically significant differences among high schools where the pre-service teachers graduated based on their digital literacy perceptions, are presented in

Table 7.

One-way analysis of variance showed that the pre-service teachers digital literacy perceptions did not differentiate significantly by the high schools where they graduated (F (4,290) = 1.291, p = 0.274). This could be also seen in interviews precisely. Some excerpt as follows:

Participant 23: I do not think my high school education did contribute to my digital skills as we did not have any related courses during that time. I learned myself and with the use of PC and smartphone.

Participant 18: We did not have such a course at all.

Participant 43: My high school did not make any contribution about digital literacy skills as there was traditional education there. Also I think that high school teachers are not sufficient in digital literacy skills.

Participants’ opinions regarding the contributions of their high school education into their digital literacy skills are given in

Table 8.

As seen in

Table 8, of the participant, 35 (70%) indicated that their high school education did not provide any contribution as they did not have any relevant course at all. In addition, 5 (10%) participants indicated that the computer course they received contributed in providing some digital skills. Four (8%) pointed out that interactive white-boards helped them to acquire some digital skills. On the other hand, 3 (6%) stated that they received traditional learning approaches and no contribution in this regard was gained. Similarly, 3 (6%) pointed out that their teachers were inadequate in this regard so they were not being able to encourage their students to gain digital skills. The findings, showing whether the pre-service teachers’ digital literacy perceptions differentiate statically by their mother education levels, are presented in

Table 9.

One-way analysis of variance showed that the pre-service teachers’ digital literacy competency beliefs differentiated significantly by their mother education levels (

F (3,291) = 4.758,

p = 0.003). Post-hoc multiple comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that the mean score for the pre-service teachers, whose mothers have undergraduate degree (

M = 3.92, S

D = 0.52), was significantly different than pre-service teachers whose mother have only elementary school education certificate (

M = 3.52,

SD = 0.70). The finding showing whether the pre-service teachers’ digital literacy competency perceptions differentiate statically by their father education levels is presented in

Table 10.

One-way analysis of variance showed that the pre-service teachers’ digital literacy perceptions differentiated significantly by their father education levels (F (3,291) = 6.690, p = 0.000). Post-hoc multiple comparisons, using the Tukey HSD test, indicated that the mean score for the pre-service teachers whose fathers have undergraduate degrees (M = 3.85, SD = 0.52) was significantly different than the pre-service teachers whose fathers have only elementary school education certificate (M = 3.56, SD = 0.63) and whose fathers have only middle school education certificate (M = 3.45, SD = 0.73). In addition, the mean score for pre-service teachers whose fathers have only high school education certificate (M = 3.87, SD = 0.59) was significantly different than the pre-service teachers whose fathers have only elementary school education certificate (M = 3.56, SD = 0.63) and whose fathers have only middle school education certificate (M = 3.45, SD = 0.73). Parent educational background was also an important factor as indicated in the interviews. Some responses to the question of how they think educational background of their parents influenced their digital skills development process are as follows:

Participant 37: I think my family helped me to become aware of these sorts of skills at early age as well as to develop easily outside of the school.

Participant 8: The family has an important role to support their kids regarding digital literacy as the education begins within the family. The kids of the family that use technological tools well would become mingle with the technology more or less.

Participant 17: My mother and father graduated from the primary school. I think they restrain if need be.

Participants’ opinions regarding how educational background of their families influenced their digital literacy development process are given in

Table 11.

As seen in

Table 11, of the participant, 28 (56%) indicated that their parents directed them to become aware of technological developments and improve their skills in this regard. However, 20 (40%) pointed out that their parents were not be able to support them as technology was not enhanced back then. In addition, 2 (4%) stated that their peers were more influential than their parents in gaining positive attitudes towards digital technologies. The findings, showing whether pre-service teachers’ digital literacy perceptions differentiate statically by the frequency of internet use, are presented in

Table 12.

One-way analysis of variance showed that the pre-service teachers’ digital literacy perceptions differentiated significantly by the frequency of internet use (F (4,290) = 6.028, p = 0.000). Post-hoc multiple comparisons, using the Tukey HSD test, indicated that the mean score for pre-service teachers, who use internet more than 4 h a day (M = 3.85, SD = 0.61), was significantly different than the pre-service teachers who use internet 1–2 h/s a day (M = 3.19, SD = 0.88), 3–4 h a day (M = 3.53, SD = 0.90), 1–2 h/s a day (M = 3.43, SD = 0.60), and 3–4 h a day (M = 3.58, SD = 0.70) respectively. Similar findings emerged in the interviews when asked how the time duration they spent on the internet reflects on their digital literacy perceptions and beliefs as follows:

Participant 49: I spend a lot of time on the internet. Depending on how we spend time on the internet, the response to this question varies but it often forms a positive perspective.

Participant 24: I spend approx. 3 h on the internet in a day and I do not think digital literacy is too much of a concern as I usually hang out on the social media.

Participants’ opinions regarding how the time duration they spent on the internet reflect on their digital literacy perceptions and beliefs are given in

Table 13.

As seen in

Table 13, of the participant, 24 (48%) indicated that this depends on what they are dealing with on the internet. In addition, 10 (20%) pointed out that they can be more familiar with these sorts of skills and more practical in finding ways to solve the problems by spending more time on the internet. Six (12%) stated that the more they spend time on the internet, the more positive perceptions they have. On the other hand, 6 (12%) stated that they mainly spend time on social media when they are online, which may not affect their digital literacy skills. Two (4%) indicated that they spend too much time on the internet, which affects them negatively in respect of various issues. The findings, showing whether the pre-service teachers’ digital literacy perceptions differentiate statically by the internet access tools, are presented in

Table 14.

Based on

Table 14, the results indicated that pre-service teachers’ digital literacy perceptions, were statistically differentiated by the internet access tools (

t (293) = −3.199,

p = 0.002) in favour of the pre-service teachers using Laptop. However, the vast majority of the participants in the interview indicated that they prefer smartphones to access the internet as they are more useful and help to save time:

Participant 4: Thanks to smartphones that are already available at all times, we are often in the digital platforms and exchange information more.

Participant 19: Smartphones improve digital literacy skills as information is available instantly and anytime and anywhere.

Participant 28: I am using my smartphone mostly but as the screen is small I am getting bored on the phone. I am using my Laptop for courses or films and videos. I think the productivity of the Laptop is better than smartphone.

Participants’ opinions regarding how having a smartphone could be related to digital literacy skills are given within themes are given in

Table 15.

As seen in

Table 15, of the participants, 29 (58%) indicated that information is available anytime anywhere due to smartphones, which enabled them to improve their digital skills. Furthermore, 15 (30%) pointed out that they can easily access the internet on the smartphone and they could handle almost anything with them. In addition, 6 (12%) stated that they could always be present in digital platforms with their smartphones and exchange information.

4. Discussion

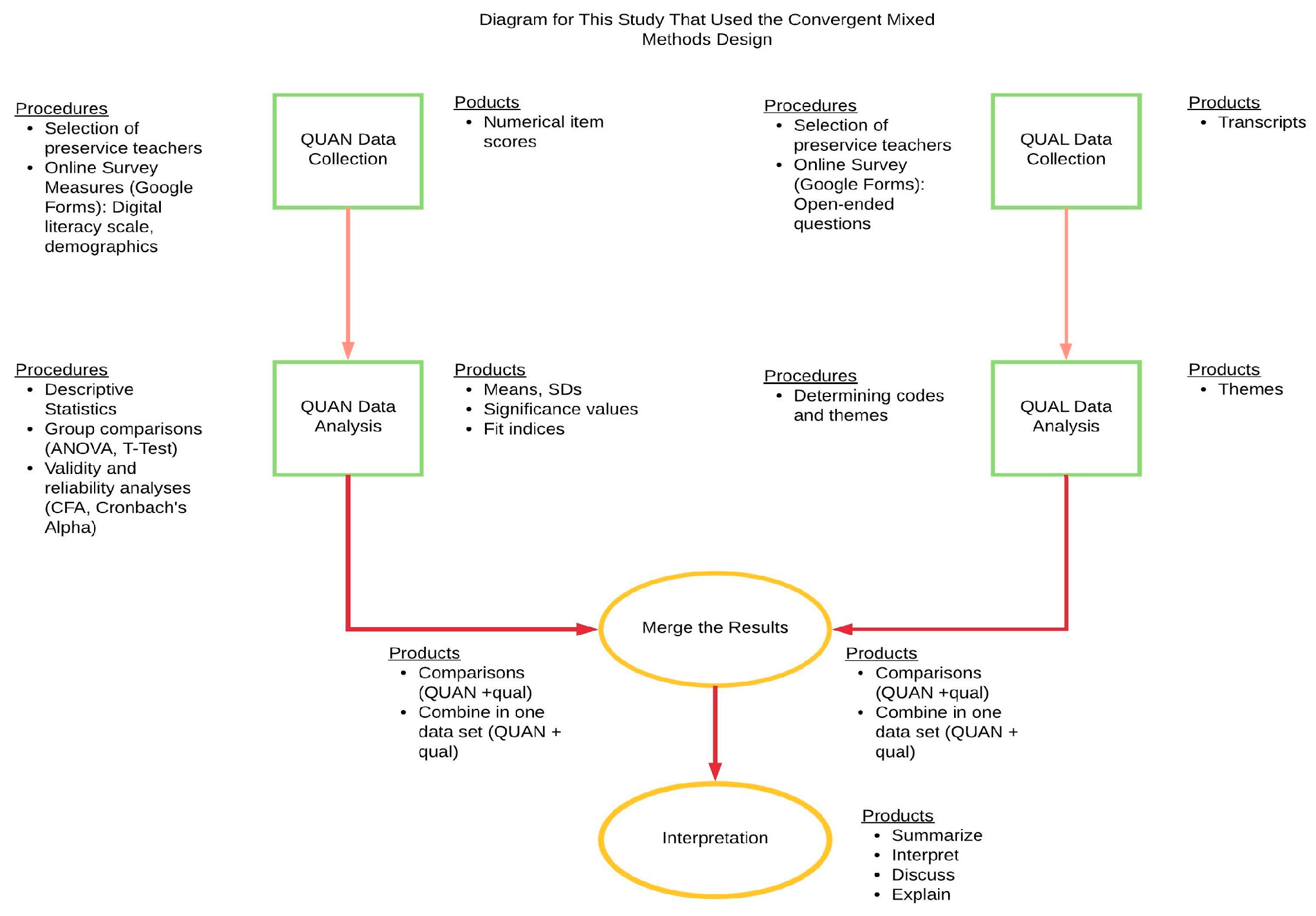

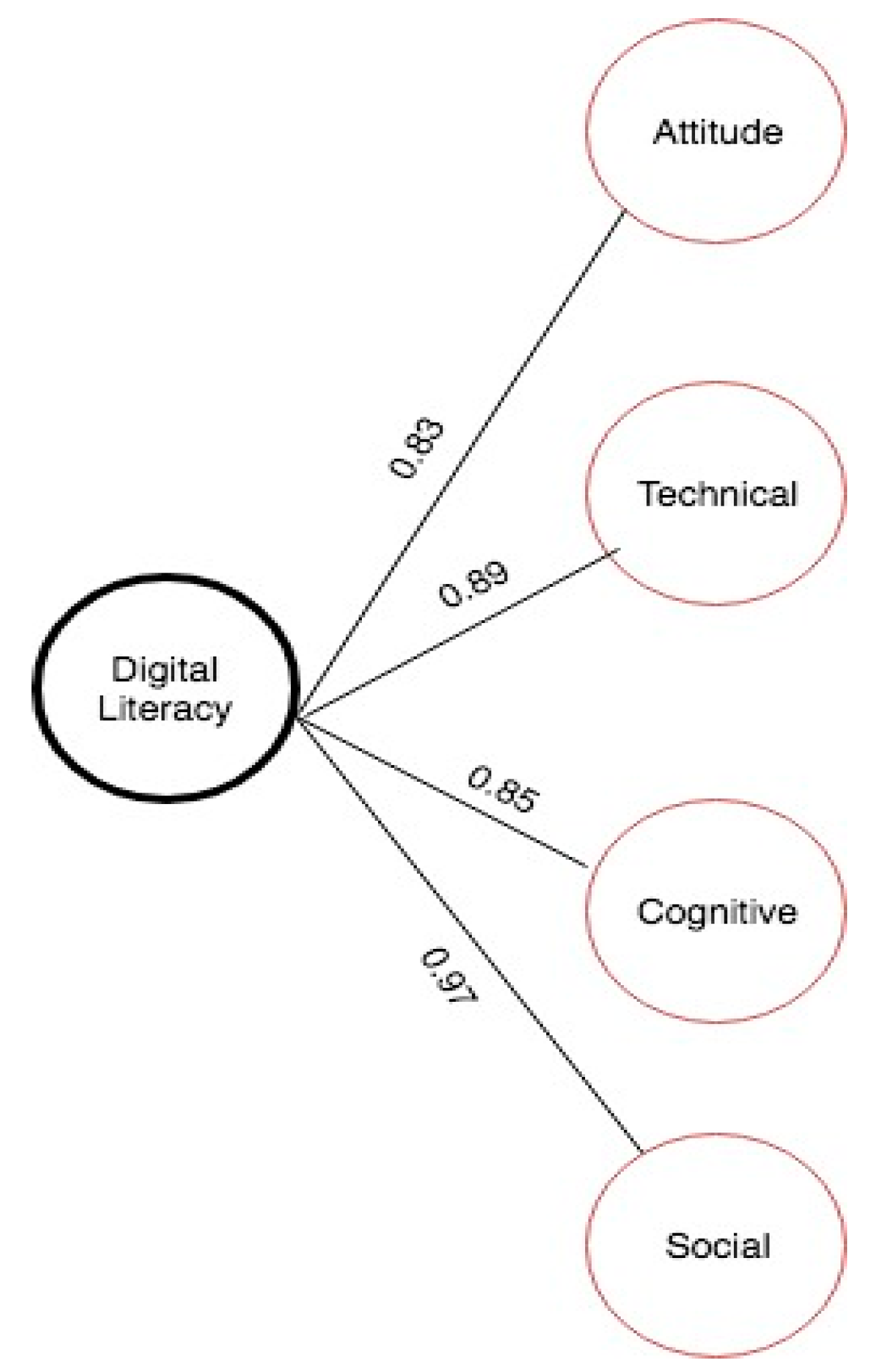

In this section, the research questions were discussed in the direction of the findings obtained in this research and compared to the relevant study findings in the literature. The study consisted of 295 first year pre-service teachers, enrolled in different teacher education programs in an education faculty. The study was based on a mixed design in order to realize the basic aim of the study: To identify digital literacy perspectives of the students within a broad sense. The model showed a good fit with the data and standardized regression weights indicated that attitude, technical, cognitive, and social factors were significant predictors of digital literacy. Furthermore, it was identified that the pre-service teachers had high and positive perceptions of digital literacy competency, indicating more confidence in using digital literacy skills. That is to say, the participants believed that they have the variety of skills, which are both cognitive and technical, to use diverse technologies appropriately and effectively to search for and retrieve information, interpret search outcomes, and judge the quality of the information retrieved. This finding is consistent with various studies in the literature [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26].

In this study, a significant gender difference was observed in favour of male-related perceptions of undergraduate students regarding digital literacy, suggesting that males show a stronger digital propensity, and that technology-related issues are more challenging for female pre-service teachers. However, results regarding this issue vary in the literature. Although this study finding is in line with some studies in the literature [

27], some other studies point out that gender does not matter in this regard, which was also highlighted by the vast majority of participants in the interviews in this study [

28,

29,

30,

31], or on the contrary, females out-perform males in the overall digital literacy test score [

32,

33]. Therefore, gender differences in this study might be due to the existence of measurement bias, which might indicate that an assessment instrument is used to measure digital literacy perceptions for females and males.

A significant difference was observed between digital literacy perceptions of participants by their majors, which were in favour of science. This finding is supported by some study results in the literature indicating that pre-service science teachers’ digital literacy skills are generally qualified [

34]. This might be due to fact that the students in the science education program receive more technology related courses as well as appropriate stewardship of information and thus students’ perceptions are rather positive. On the other hand, the perceptions of the pre-service teachers were differentiated significantly in relation to the high school in which they graduated. As the vast majority of the participants indicated in the interviews that they had not received any relevant course designed to cultivate their digital skills when they were in high school, this finding was not surprising. This finding probably also makes apparent that they were not included in any digital literacy practices outside of the context of the school and were not familiarized with this genre and its unique conventions. Furthermore, the quantitative data showed that the pre-service teachers’ digital literacy perceptions were differentiated significantly by their parent education levels and family education background. These seemed to be important factors that affected participants’ digital skills in the interviews. This finding was also supported by other study results in the literature [

35,

36]. This finding indicated that an individual whose parent is well-educated is more likely to become a digital literate participant. However, interestingly it was revealed that the effect of digital literacy on academic achievement is stronger with low parental educational background, suggesting that digital skills might act as a substitute for family background [

37].

The pre-service teachers’ digital literacy perceptions were differentiated significantly by the frequency of internet use, suggesting that the more they are involved in time-consuming online applications, the more they have sophisticated digital skills and a broader range of online activities, even if there may be risk factors present, such as developing problematic patterns of internet use. In many ways, this leads them to be familiar with the digital technologies and the internet. However, the problem is that being familiar and being literate are not necessarily the same thing. They might be comfortable in using digital tools but lack the refined cognitive skills to find, evaluate, create, and communicate. Furthermore, participants also indicated that social media, watching films, videos and music and communication (FaceTime, email, etc.) are the main uses of the internet. A lot of studies in the literature point out similar results [

38,

39,

40]. On the other hand, perhaps surprisingly, another finding indicated that the pre-service teachers’ digital literacy perceptions, which are statistically differentiated by the internet access tools in favour of the pre-service teachers using laptops, suggesting that the user experience on a smartphone might be very different from that on a laptop.