Abstract

As projects are evolving from tactical level ‘tasks’ to societally-relevant ‘instruments of change’, the theories, methods, and practices of project management need to evolve, too. Academic programs on project management, logically, should be frontrunners in this development, which calls for societally-relevant and ‘responsible’ project management education. Following the model of the United Nations Principles for Responsible Management Education, some first ideas on what Responsible Project Management Education should entail developed. The study presented in this article uses meta-synthesis to explore the meaning and characteristics of responsible project management education. The study concludes nine characteristics that provide a conceptual starting point for more empirical research on the topic.

1. Introduction

Project management is still a relatively young discipline. Fueled by the extraordinary manufacturing efforts that the Second World War required, the methods that today are seen as typical project management methods emerged in the 1940s and 1950s from the field of Operations Research [1]. The first degree course in project management only opened some 50 years ago at the University of New South Wales in Australia. In these early stages, projects were limited to specific industries and project management was about optimizing the schedule and duration of a project by using quantitative techniques [2].

Today, organizations in all types of industries are undertaking projects as a growing part of their business activities, even when their core business processes are repetitive [3]. As a recent study into the position of projects in three Western European countries showed that projects account for roughly one third of all economic activity [4], a ‘projectification’ of society [5] can be observed. Following this development, a growing number of authors (for example [6,7]) point out that the role projects play in society requires a more holistic and societally oriented approach to project management. Societies, as social systems, have specific values, norms and rules [8]. The emerging societal orientation of project management therefore requires a value-based and ethical approach to the profession [9]. Project management needs to be ‘responsible’ [10].

This call for responsibility is also heard within the context of (general) management education and business schools. In 2007, a United Nations international task force of deans, university presidents, and representatives of leading business schools and academic institutions, developed six “Principles for Responsible Management Education” (PRME). The objective of these principles is “to raise the profile of sustainability in schools around the world, and to equip today’s business students with the understanding and ability to deliver change tomorrow.” [11]. Given the role that projects play in realizing societal change [12], these principles should also be considered relevant to project management education. However, it took ten years before Cicmil and Gaggiotti [13] referenced the PRME principles in a first attempt to develop principles for “Responsible Project Management Education”.

Applying the PRME principles to project management education logically suggests that, in education, projects are discussed within a societal context [7]. However, responsibility in education also refers to the plurality of perspectives that is offered. With regards to this plurality, Cicmil and Gaggiotti [13] observed that project management standards, trainings, and education do not reflect the diverse range of methodological, epistemological, and ontological perspectives that can be found in research in project management [14]. Project management standards, trainings and education are often still dominated by the traditional ‘command-and-control model’ of project management [13], that does not represent the complex, ambiguous and unpredictable reality of projects. In line with this, Hussein et al. [15], conclude that “It is vital that project management education programs and instructors adopt learning aids and teaching strategies that present and discuss these characteristics with a more active approach rather than depending solely on a theoretical approach through emphasizing terms and concepts.”. ‘Responsible’ Project Management Education, therefore, needs to reflect plurality in perspectives and approaches.

This article explores this emerging concept of Responsible Project Management Education and aims to provide a set of guiding statements or principles that may function as a holistic vision on what the characteristics of a responsible project management training or education program should be. With this paper, the author aims to contribute to a discussion on the way project management is trained and educated, especially in higher education.

2. Methodology

As this study aims to develop our understanding of a quite new phenomenon, it is considered to be of an exploratory nature. The study applied meta-synthesis as its core methodology. The term meta-synthesis was coined by Stern and Harris [16], with reference to the amalgamation of a group of qualitative studies. It is, therefore, a relatively new technique for examining qualitative research [17] and seeking to understand and explain phenomena. The methodology has been applied in diverse areas such as transformational leadership [18], concepts of caring [19], and adaptation to motherhood [20].

With respect to knowledge creation, interpretive research approaches are often approached more critically than positivist approaches [21]. Meta-synthesis is, therefore, also not without criticism: “the synthesis of tentative, somewhat equivocal findings of qualitative research methods into some kind of more comprehensive understanding or even explanatory theory of phenomena is viewed with suspicion” [22]. Countering these arguments is the claim that reconciling ‘islands of knowledge’ around a certain phenomenon is a crucial step in developing relevance of interpretive insights.

This study reported in this article followed the process of meta-synthesis described by Walsch and Downe [22]. The object of study was framed as “Responsible Project Management Education”. As this topic as a search string in Google Scholar only delivered the abovementioned article of Cicmil and Gaggiotti [13], the search was expanded to the topics of “Responsible Management Education” and “Responsible Project Management”. By using selecting Google Scholar as search engine, the study followed the recommendation by Bauer and Bakkelbasi [23] that “researchers should consult Google Scholar …, especially for a relatively recent article, author or subject area.”. For data extraction, we used the databases Science Direct, Business Source Premier, EBSCO-Host, and JSTOR, as well as the ResearchGate network, to retrieve the full publications. Selection of relevant articles was done based on the abstracts.

The search string “Responsible Management Education” delivered well over 2000 results in Google Scholar. Most of these publications refer to the United Nations Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME), as the “most solid initiative to inspire and champion responsible business education globally” [24]. However, also other sources were found.

The search string “Responsible Project Management” delivered 176 results, with most of these referring to the social and environmental impacts of projects. Only three publications specifically focused on the concept of responsibility in project management. As published meta-synthesis have been framed rather broadly, it was decided to also include related topics, such as sustainable development in project management, in the exploration.

The study used qualitative content analysis methods to analyze the articles. In this analysis, we combined the conventional, directed, and summative content analysis approaches [25]. As meta-synthesis is in its infancy, little has been written about how rigor can be applied to the synthesis of literature [22]. Especially in the case of meta-synthesis, which is not primarily aimed at finding commonalities between different concepts and studies, but at creating new concepts from the intent or meaning of existing concepts. Hermeneutic intent needs to be preserved so that the richness and intricacies of meaning are revealed.

The study therefore took a reflective approach to the synthesis and, as the result of this reflection, derived a model of influencing concepts of Responsible Project Management Education, and a set of characteristics, that will be presented after the discussion of the literature.

3. Literature

3.1. Responsible Management Education

As most publications on Responsible Management Education refer to the United Nations PRME principles, these principles provide a logical starting point for our exploration. The six PRME principles (presented in Table 1) have been undersigned by almost 700 leading business schools from over 85 countries [11].

Table 1.

The six PRME principles [11].

The publication of the PRME in 2007 accelerated scholarly interest in the topic of responsible management education [26], today resulting in over 350 publications specifically on this topic, of which some 80–100 can be classified as peer-reviewed research-based publications. The vast majority of published peer-reviewed research on the topic is provider-centric, focusing on how to organize for responsible management education [26].

With regards to the content of management education, responsible management education especially requires a deeper understanding of ethics and ethical considerations in management practices [27]. As most management education evolved primarily from the strive for economic growth and wealth, the notion of other responsibilities of organizations, such as contributing to a wider set of interests of diverse groups of stakeholders, was side-lined for many decades [28]. Today, ethics and (corporate) social responsibility might be part of most MBA curricula, but the translation of these considerations in managerial competencies remains to be developed.

The United Nations PRME principles do not only refer to the content of education. The PMRE encourage management education to actively address, and continuously refine: clarity of purpose and values, effectiveness of teaching methods, relevance of research, diversity of partnerships with relevant groups and open and critical dialogue. Adopting the PMRE, therefore, impacts the pedagogy of management studies as much as its content [29].

These two perspectives on responsible management education, content, and pedagogy, provided a structure for our exploration. Responsible Project Management Education is about educating responsible project management (referring to the content of project management education) as well as responsible education of project management (referring to the pedagogy of this education).

3.2. Responsible Project Management

As is shown from our literature search, described in the methodology section, the concept of responsible project management has not yet been strongly developed in literature. The Google Scholar search only delivered three specific hits. The most developed publication on the topic is the article of Tinico et al. [30] that aims to develop a framework for responsible project management. In this framework, the authors combine insights from three fields of research: (1) accountability for impacts of projects, (2) sustainability in project management; and (3) responsible innovation.

3.2.1. Impact and Accountability

The attention for accountability results from the article of Flyvbjerg et al.’s [31], about megaprojects. In this article, the authors argue that megaprojects fail to accurately assess or forecast their environmental and environmental impacts and risks.

Flyvbjerg et al. refer to the ‘hiding hand’ principle that says that projects planners often underestimate the challenges that may occur in a project, but that they also underestimate the creativity of people to handle these unforeseen challenges. As a result, projects that would not have been approved when all challenges and risks would have been known upfront, still got realized. Despite that this may not necessarily always be a bad thing, the underestimation of challenges, and risks raises questions about responsibility and accountability. The misestimating of risks, costs, and benefits is not in the interest of the investors in the project and other stakeholders [31]. Flyvbjerg et al. [31] therefore propose to improve accountability in the decision making about projects, by improving (1) transparency, (2) orientation on the goal of the project instead off the solution, (3) engaging in a constructive and responsive dialogue with all stakeholders, (4) developing the regulatory regime to support accountability of project, and (5) establishing project funding in the form of risk capital, which would provide a more realistic assessment of the risk/return relationship of the investment in the project.

And although the work of Flyvbjerg et al. was oriented at megaprojects, responsibility, and accountability in projects is also discussed more in general. For example Schieg [6] refers to the concepts of (corporate) social responsibility within the context of projects, in which accountability and transparency are key-principles [32].

3.2.2. Sustainability in Project Management

Responsible management education is frequently associated with sustainability and sustainable development [33]. Following the 1972 book “The Limits to Growth” [34], that predicted that the exponential growth of world population and world economy would result in overshooting our planet’s capacity of natural resources, the concerns about sustainability and sustainable development became broadly recognized as a political, societal and managerial challenge [35]. For the universities and institutions educating future managers and business leaders, this challenge includes developing “responsible leaders who are prepared to deal with complex and value-laden issues in economy and society” [33].

This relationship between sustainability and project management is one of the most important global project management trends today [36] that is being addressed in a growing number of studies and publications [37,38]. From the emerging literature on this topic, two types of relationship between sustainability and project management appeared [39,40]: the sustainability of the project’s product, the deliverable that the project realizes and the sustainability of the process of delivering and managing the project. The first relationship is well studied and addressed, for example in relationship to eco-design and for the construction of ‘green’ buildings. The second relationship, sustainable project management, is less established. However, Silvius [7] identifies an emerging sustainability ‘school of thought’ in project management, that is defined by the following four characteristics.

- Projects in a societal perspectiveThe Sustainability school adopts a societal perspective on projects and considers projects as instruments to realize societal change. “Organizations, nowadays are increasingly keen on to include sustainability in their business. Project management can help make this process a success but little guidance is available on how to apply sustainability to specific projects.” [12]. The earlier observed ‘projectification’ of societies [4], justifies this societal perspective. However, the role of projects in society is not limited to economic value. The Sustainability school elaborates on this societal role by considering also the social and environmental impact of projects.

- Management for stakeholdersSeveral authors, for example Eskerod and Huemann [41], recognize the need for a more open and proactive engagement of stakeholders as a consequence of integrating sustainability into project management. They conclude that the current standards of project management guide practitioners towards the recognition of a rather limited group of stakeholders and to “selling the project to the most important stakeholders rather than involving them and their interests into the creation of project objectives” [41] (p. 43). Referring to stakeholder theory [42], they differentiate between a ‘management of stakeholders’ approach and a ‘management for stakeholders’ approach. In the management of stakeholders approach, stakeholders are seen primarily as providers of resources. The project needs the stakeholder to fulfil its purpose. The stakeholders are means and stakeholder management is the instrument used to make the stakeholders fulfil their role and prevent them from hindering the project. In contrast, the management for stakeholders approach, recognizes all stakeholders as having their own right and legitimacy. They are not defined by their role in the project, but by their interests. “Stakeholders are not means to specific aims in the organization but valuable in their own rights.” [40,41]. This recognition implies that the orientation of the management of the project should be to shape the project in such a way that it combines the interests of many of the stakeholders and thereby provides value to many of them.

- Triple bottom line criteria.Integrating sustainability in project management will influence the specifications and requirements of the project’s deliverable or output, and the criteria for project success. For example the inclusion of environmental or social aspects in the project’s objective and intended output and outcome. The triple bottom line concept states that sustainability is about the balance or harmony between economic, social, and environmental sustainability [37]. Introducing the triple bottom line perspectives into the requirements and success definition of projects creates the challenge of definition and measurability. Several frameworks or sets of sustainable development indicators (SDIs), are specifications of the triple bottom line. Unfortunately, there is not a unified understanding of what are relevant indicators for sustainability. Nevertheless, SDI frameworks may help in operationalizing the concept, however, they also introduce the risks that the interrelations between the three perspectives of the triple bottom line are overseen and that the social, environmental, and economic perspectives are each considered in isolation. The holistic understanding of sustainability requires an integration of economic, environmental, and social perspectives [43].

- Values-basedSustainability inevitably is a normative concept, reflecting values and ethical considerations of society. “Sustainability is the ideal state of sustainable development efforts” [44], which is based on the ethics and values of the actors. Following the conclusion that sustainability is embedded in the values of the social system that the sustainability relates to, a logical question is which values sustainability is based upon. In the earlier quoted Brundtland commission’s definition of sustainable development, the statement “…the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations…” [45] implies equality as a value of sustainability. In the definition, equality is applied to the rights of different generations, but the value may also be applied to the interests of different stakeholders. This interpretation can be found with the earlier mentioned stakeholder theory. Other values associated with sustainability are participation, fairness, respect, transparency, and traceability.

3.2.3. Responsible innovation

Responsible innovation proposes that research and innovation processes must be responsive to societal challenges [46]. Based upon the realization that science, technology, and innovation (STI) have allowed society to have important achievements, responsible innovation challenges scientists, technologists, innovators, firms, and policy-makers to develop STI that combine economic and public values and match the demands of society.

Responsible research and innovation is defined by Schomberg [47] (p. 63) as “A transparent, interactive process by which societal actors and innovators become mutually responsive to each other with a view to the (ethical) acceptability, sustainability and societal desirability of the innovation process and its marketable products (in order to allow a proper embedding of scientific and technological advances in our society).”. Stilgoe et al. [48] propose the following four dimensions to be considered in research and innovation processes, which aim at make research and innovation more responsible by raising, discussing and responding to societal concerns and interests.

- AnticipationAnticipation involves systematic thinking aimed at increasing resilience, while revealing new opportunities for innovation and the shaping of agendas for socially-robust risk research and innovation. Negative implications of new technologies and innovations embedded in megaprojects are often unforeseen and risk-based estimates of harm have failed to provide early warnings. Therefore, anticipation calls for stakeholders to ask specific questions about what if…? to consider contingency, what is known, what is likely, what is plausible and what is possible. Anticipation faces institutional and cultural resistance [48], for which reflexivity and inclusiveness might be helpful to bring new knowledge and values that might help to overcome the resistance.

- ReflexivityReflexivity involves recognizing and systematically reflecting upon social and ethical issues of decision making, while otherwise carrying out normal routines and practices [49]. Reflexivity means holding a mirror up to one’s own activities, commitments, and assumptions, being aware of the limits of knowledge and being mindful that a particular framing of an issue may not be universally held [30].

- InclusionInclusion is a process of moving beyond engagement with the stakeholders to include members of the public. It uses multi-stakeholder partnerships, forums, advisory committees, and other mechanisms to diversify the inputs to, and delivery of governance [48]. However, inclusion also leads to power issues among stakeholders, since their differences in expectations that underpin the dialogue might favor powerful parties.

- ResponsivenessResponsiveness is the coupling of reflection and deliberation to actions that influence the direction and trajectory of innovation [46]. It requires a capacity to change shape or direction in response to stakeholder and public values and changing circumstances [48]. In a much broader sense, responsible innovation calls for institutionalized responsiveness for the coupling of anticipation, reflexivity and deliberation to action. For example, where companies highlight benefits and NGOs risks, co-responsibility implies that agents have to become mutually responsive [30]. It means firms have to go beyond the short-term benefits and NGOs have to reflect on the constructive role of new technologies and innovations. In other words, responsiveness implies responding to changes as they arise. It requires sufficient discussion between stakeholders on the possible positive and negative consequences of STI and/or projects. Moreover, these consequences need to be visibly responsive to the society as a whole [46].

The framework of responsible innovation dimensions still lacks conceptual weight [30]. However, it appears in academic and policy literature and debates around contested areas of science and technological progress [48].

3.2.4. Reflection

The three fields of research that Tinico et al. [30] draw upon in their development of a framework for responsible project management have in common that they all relate to projects, their governance and management. Additionally, the field of responsible innovation refers to projects when it discusses research and innovation. All three fields, therefore, provide relevant input for the content of Responsible Project Management Education.

It should be observed that the more recently evolved agile approach to projects and project management may already be a step towards responsible project management, as the agile approach is more responsive to changes. Several agile approaches refer to product development and innovation as their foundation and agile approaches also appear more suitable to integrate the concepts of sustainability into the management of projects [50].

3.3. Responsible Education of Project Management

Responsible education of project management refers to the pedagogy and educational methods that are used in project management education. As mentioned earlier, the United Nations PRME principles also explicitly mention the pedagogical aspects of management education by referring to the effectiveness of teaching methods, and the open and critical dialogue with diverse relevant groups [29]. On the pedagogical aspects of responsible management education, Holman [51] suggests that in order to prepare managers for the real world, in which managerial practice is often complex and non-mechanistic, management education should include epistemological plurality and alternative pedagogies, such as experiental learning and reflextion. This theoretical plurality is also at the heart of the earlier referenced work by Cicmil and Gaggiotti [13], that coins the idea of principles for Responsible Project Management Education. As already referred to in the introduction, observe that in handbooks, standards and trainings on project management is often depicted as the a-contextual application of a set of universally applicable tools and techniques. Turner et al. [52] refer to the infamous advertisement for a project management software tool that claimed that “If you can move a mouse, you can manage a project”, to underline the popular perception of project management as the application of a set of tools and techniques.

In this view, the project manager is knowledgeable, has clear preferences, access to adequate information and a clear organizational status [53]. The nature of project management in reality, however, is much more complex, as projects are situated in “an unpredictably evolving context of shifting currents in corporate strategies and paradoxical conditions of the dominant socio-political world order” [13].

Responsible Project Management Education, therefore, promotes a more holistic view of project management, through the adoption of the following principles [13]:

- Introduce theoretical plurality by promoting a wider, research-informed reading to expose the fragmented nature of the project management field and a range of competing models, theories, methods, and arguments. Legitimize and encourage critique on the very object of the study (project and project management) and its discursive nature.

- Encourage a critical debate of accountabilities, challenges, and anxieties associated with acting in an economically sound, environmentally friendly, and socially responsible way in complex project environments.

- Curriculum should be informed, developed and delivered through partnership and dialogue with practitioners, students, academic researchers, and professional bodies; cultural sensitivity needed in discussing their contextualized experiences with projects and project management and unavoidable interests/agenda’s at play.

- Assessment forms which foster theorizing, involving knowledge creation through reflection on the lived experience and awareness of situational ethics in a concrete project context.

4. Responsible Project Management Education

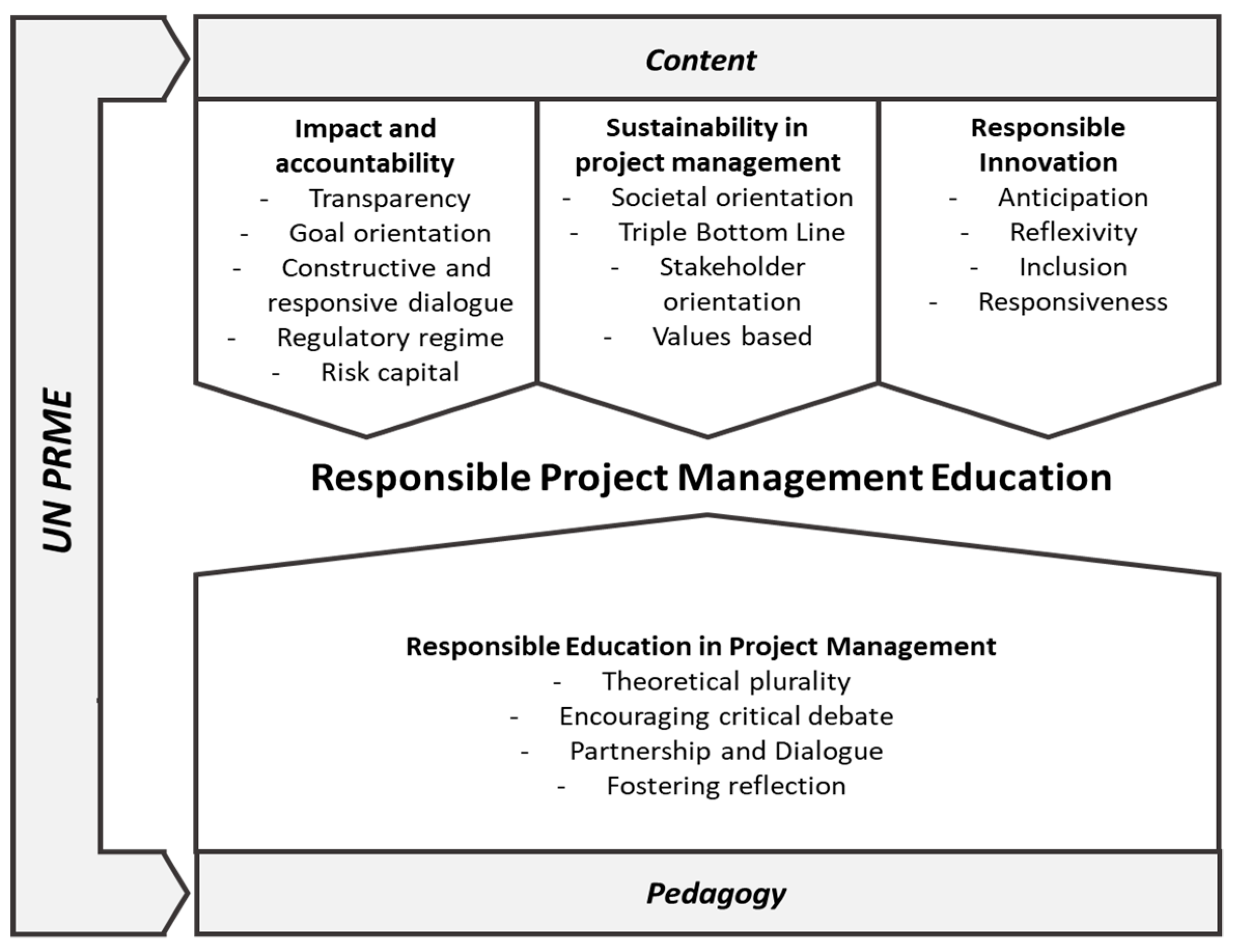

The previous section analyzed the content and pedagogical aspects of Responsible Project Management Education. The influences found in literature are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the concepts influencing Responsible Project Management Education.

4.1. Conceptual Model

The model showed in Figure 1 synthesizes the main concepts found in literature. On the content of Responsible Project Management, these were the frameworks that addressed the impact and accountability of projects, sustainability in project management and responsible innovation. On the pedagogical aspects of Responsible Project Management Education, the principles developed by Cicmil and Gaggiotti [13] provide orientation. It may be noted that both content and pedagogical frameworks and aspects build upon the United Nations PRME principles.

4.2. Characteristics

Based upon the influencing concepts presented in Figure 1, we propose the following characteristics of Responsible Project Management Education (Table 2).

Table 2.

Nine characteristics of Responsible Project Management Education.

In these nine characteristics, the PRME principles are chosen as the main structure, in order to simplify implementation.

4.3. Discussion

4.3.1. Purpose

In responsible project management, projects are seen as temporary organizations that realize change in organizations or across organizational boundaries [50]. This change or “organizational” perspective on projects, contrasts the traditional “task” perspective on projects in which projects are seen as temporary endeavors of carrying out given tasks [55]. In the task perspective, the project is ideally detached from the rest of the world and the project team should concentrate fully on carrying out the task. In the organizational perspective, the project is “a temporary organization, established by its base organization to carry out an assignment on its behalf” [55]. In this perspective, the purpose of the project is to create value for its base organization.

It can be argued that responsible project management elaborates on the organizational perspective on projects and project management by positioning the purpose of the project in a societal context [7]. Positioning projects in a wider context adds uncertainty and ambiguity, hence the need to provide students with a wide set of readings that covers a wide range of competing models, theories, methods, and arguments.

4.3.2. Values

Projects are not value-neutral. Projects are, just as the organizations and society they are part of, social systems, that inevitably have specific values and norms [8]. These values are logically influenced by the values of the team members and the surrounding social systems, and should also be congruent with the values of the organizational and societal context [50].

Responsible project management should, therefore, reflect the values and ethics that are considered ‘responsible’ by organizations and society. Values that can be derived from this societal perspective are equality, participation, fairness, respect, honesty, and transparency [7].

4.3.3. Method

In their proposal for principles of Responsible Project Management Education, Cicmil and Gaggiotti [13] conclude that this education needs to reflect the plurality in perspectives and approaches that appears also in project management research. An illustration of this plurality are the nine schools of thought in project management that were extensively discussed in a series of articles in 2007/2008 [56,57,58,59,60,61].

These nine schools of thought, or even ten with the sustainability school added by Silvius [7], provide a variety of perspectives that goes far beyond the standards for project management, such as the Project Management Institute’s project management body of knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), the Axelos’ PRojects IN Controlled Environments (PRINCE2®) and the ISO 21500:2012 Guidance on project management [62]. These standards focus on shared practices and ‘common denominators’, generally referred to as ‘best practice’, of project management, whereas the reality of projects is infinitely more diverse.

Responsible project management therefore calls for critical reflection and questioning of standards, practices, assumptions, perspectives and theories. This criticality cannot be ‘taught’ in the traditional way, but requires a pedagogic strategy that centers on dialogue as the dominant process and a learning-with approach that emphasizes mutual student-teacher responsibility in the learning process [63].

4.3.4. Research

As research is the foundation of (higher) education, also responsible project management requires a research based foundation. As the societal perspective on projects and project management is quite new and still emerging [7], its presence in project management research is still limited. Responsible Project Management Education is, therefore, called upon to, through educational activity, also make a contribution to the research in this field.

4.3.5. Partnership and Dialogue

Both the United Nations PRME and Cicmil and Gaggiotti [13] point out the importance of partnership and dialogue in education, in order to exchange experiences and perspectives between practitioners, students, academic researchers and professional bodies. Although, these groups not easily engage with each other, and often also not speak the same language, it should be their shared interest to progress the profession. Additionally, this progress comes through reflection, discussion, and dialogue.

5. Conclusions and Contribution

As project management is evolving from a tactical level capability within organizations, to a societally relevant “way to sustainability” [12], the theories, methods, and practices of project management need to evolve too. The agile approaches to projects and project management may be a first step, but responsibility in project management calls for more than what is, today, understood with agility. Academic programs on project management should be frontrunners in providing diverse and relevant perspectives on project management, which first publications are labeling as Responsible Project Management Education.

The study reported in this paper explored the characteristics of Responsible Project Management Education, based on a framework of influencing concepts that addresses both the content and the pedagogical aspects of Responsible Project Management Education. As main contribution, a set of nine characteristics was developed. With this set, existing higher education programs and courses on project management can assess themselves in order to highlight the societal responsibility of project managers in their education and training.

The interpretive nature of the study, logically, introduces limitations. However, the framework of nine characteristics is intended as a starting point of an academic debate on the topic. Further research will be needed to empirically verify and refine the set of characteristics, but the synthesis provided in this article aims to make a contribution to the discussion on and further development of Responsible Project Management Education.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft: G.S.; writing—review and editing: R.S.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Morris, P.W.G. The Management of Projects; Thomas Telford: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Huemann, M. Human Resource Management in the Project Oriented Organization; Towards a Viable System for Project Personnel; Gower Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Keegan, A.; Turner, J.R. The Management of Innovation in Project-Based Firms. Long Range Plan. 2002, 35, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoper, Y.-G.; Wald, A.; Ingason, H.T. Projectification in Western economies: A comparative study of Germany, Norway and Iceland. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, R.; Söderholm, A. Conceptualizing a project society—Discussion of an eco-institutional approach to a theory on temporary organizations. In Projects as Arenas for Renewal and Learning Processes; Lundin, R., Midler, C., Eds.; Springer US: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Schieg, M. The model of corporate social responsibility in project management. Bus. Theory Pract. 2009, 10, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, A.J.G. Sustainability as a new school of thought in project management. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 1479–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gareis, R.; Huemann, M.; Martinuzzi, A. Relating Sustainable Development and Project Management; IRNOP IX: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Biedenbach, T.; Jacobsson, M. The Open Secret of Values: The Roles of Values and Axiology in Project Research. Proj. Manag. J. 2016, 47, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laszlo, E. The evolutionary project manager. In Global Project Management Handbook; Cleland, D.I., Gareis, R., Eds.; McGraw-Hill International Editions: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. United Nations Principles for Responsible Management Education. Available online: http://www.unprme.org/about-prme/index.php (accessed on 3 February 2018).

- Marcelino-Sádaba, S.; Pérez-Ezcurdia, A.; González-Jaen, L.F. Using Project Management as a way to sustainability. From a comprehensive review to a framework definition. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 99, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicmil, S.; Gaggiotti, H. Responsible forms of project management education: Theoretical plurality and reflective pedagogies. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, J. Pluralism in project management: Navigating the crossroads of specialization and fragmentation. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, B.A. A Blended Learning Approach to Teaching Project Management: A Model for Active Participation and Involvement: Insights from Norway. Educ. Sci. 2015, 5, 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.; Harris, C. Women’s health and the self-care paradox: A model to guide self-care readiness—Clash between the client and nurse. Health Care Women Int. 1985, 6, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, L.; Allen, M. Meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Qual. Health Res. 1996, 6, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielstick, C. The transforming leader: A meta-ethnography analysis. Community Coll. Rev. 1998, 26, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, G. Meta-synthesis of qualitative analyses of caring: Defining a therapeutic model of nursing. Adv. Pract. Nurs. Q. 1997, 3, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, C. Mothering multiples: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Matern. Child Nurs. 2002, 27, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J. Social Perspectives on Pregnancy and Childbirth for Midwives, Nurses and the Caring Professions; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Walsch, D.; Downe, S. Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: A literature review. J Adv Nurs 2005, 50, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.; Bakkalbasi, N. An examination of citation counts in a new scholarly communication environment. D-Lib Magazine 2005, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, J.M.; Marcinkowska, M.W.; Thiruvattal, E. The UN-Principles for Responsible Management Education: Sharing (and evaluating) information on progress. J. Glob. Responsib. 2011, 2, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, J. Responsible Management Education & Learning: A Systematic Review, Taxonomy and Research Agenda. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2007, 2017, 12316. [Google Scholar]

- Izak, M.; Kostera, M.; Zawaszki, M. The Future of University Education; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, C. Representations of the intellectual: Insights from Gramsci on management education. Manag. Learn. 2003, 34, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solitander, N.; Fougère, M.; Sobczak, A.; Herlin, H. We are the champions: Organizational learning and change for responsible management education. J. Manag. Educ. 2012, 36, 337–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinoco, R.; Sato, C.; Hasan, R. Responsible project management: Beyond the triple constraints. J. Mod. Proj. Manag. 2016, 4, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B.; Bruzelius, N.; Rothengatter, W. Megaprojects and Risk. An Anatomy of Ambition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 26000:2010 Guidance on Social Responsibility; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dyllick, T. Responsible management education for a sustainable world. J. Manag. Dev. 2015, 34, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W. The Limits to Growth; Club of Rome: Rome, Italy, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Dionisi, L.E.; Turner, R.; Mittra, M. Global Project Management Trends. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Proj. Manag. 2016, 7, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, A.J.G.; Schipper, R. Sustainability in Project Management: A literature review and impact analysis. Soc. Bus. 2014, 4, 63–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarseth, W.; Ahola, T.; Aaltonen, K.; Økland, A.; Andersen, B. Project sustainability strategies: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvius, A.J.G.; Schipper, R. Developing a Maturity Model for Assessing Sustainable Project Management. J. Mod. Proj. Manag. 2015, 3, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kivilä, J.; Martinsuo, M.; Vuorinen, L. Sustainable project management through project control in infrastructure projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1167–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskerod, P.; Huemann, M. Sustainable development and project stakeholder management: What standards say. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2013, 6, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman/Ballinger: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone Publishing: Mankato, MN, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Keeys, L.A.; Huemann, M. Project benefits co-creation: Shaping sustainable development benefits. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1196–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Great Britain, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, R.; Stilgoe, J.; MacNaghten, P.; Gorman, M.; Fischer, E.; Guston, D. A framework for responsible innovation. In Responsible Innovation. Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; Owen, R., Bessant, J., Heintz, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Von Schomberg, R. A vision of responsible research and innovation. In Responsible Innovation. Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; Owen, R., Bessant, J., Heintz, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stilgoe, J.; Owen, R.; MacNaghten, P. Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.; Rip, A. Responsible innovation: Multi-level dynamics and soft intervention practices. In Responsible Innovation. Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; Owen, R., Bessant, J., Heintz, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Silvius, A.J.G.; Schipper, R.; Planko, J.; van den Brink, J.; Köhler, A. Sustainability in Project Management; Gower Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Holman, D. Contemporary models of management education in the UK. Manag. Learn. 2000, 31, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.R.; Huemann, M.; Anbari, F.T.; Bredillet, C.N. Perspectives on Projects; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, D.; Badham, R. Power, Politics, and Organisational Change: Winning the Turf Game; SAGE: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Silvius, A.J.G. Sustainability as a competence of Project Managers. PM World J. 2016, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, E.S. Rethinking Project Management: An Organisational Perspective; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bredillet, C.N.; Turner, J.R.; Anbari, F.T. Exploring Research in Project Management: Nine Schools of Project Management Research (Part 1). Proj. Manag. J. 2007, 38, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredillet, C.N.; Turner, J.R.; Anbari, F.T. Exploring Research in Project Management: Nine Schools of Project Management Research (Part 2). Proj. Manag. J. 2007, 38, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredillet, C.N.; Turner, J.R.; Anbari, F.T. Exploring Research in Project Management: Nine Schools of Project Management Research (Part 3). Proj. Manag. J. 2007, 38, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredillet, C.N.; Turner, J.R.; Anbari, F.T. Exploring Research in Project Management: Nine Schools of Project Management Research (Part 4). Proj. Manag. J. 2008, 39, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bredillet, C.N.; Turner, J.R.; Anbari, F.T. Exploring Research in Project Management: Nine Schools of Project Management Research (Part 5). Proj. Manag. J. 2008, 39, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bredillet, C.N.; Turner, J.R.; Anbari, F.T. Exploring Research in Project Management: Nine Schools of Project Management Research (Part 6). Proj. Manag. J. 2008, 39, 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Standardization. ISO 21500:2012, Guidance on Project Management; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dehler, G. Prospects and possibilities of critical management education: Critical beings and a pedagogy of action. Manag. Learn. 2009, 40, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).