Education for the Sustainable Global Citizen: What Can We Learn from Stoic Philosophy and Freirean Environmental Pedagogies?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Must fully assume its central role in helping people to forge more just, peaceful, tolerant and inclusive societies. It must give people the understanding, skills and values they need to cooperate.

2. Education for Social Transformation and Sustainable Development

2.1. A Stoic Education for Social Transformation and Sustainable Development

2.2. Freirean Ecopedagogies: Critical Analysis of Sustainable Development

It is not just education per se, but the socio-cultural and socio-political contexts in which education is delivered that matter for the transformation of society in ways that are consistent with notions of social justice. For example, in Western democratic societies, the emancipation of individuals as well as of collectives is a key aspect undergirding prevailing notions of social justice, both in terms of conscientization (Freire, 2005), and the extent of freedom that people are capable of reaching so as to identify and pursue what it is that matters to them (Sen, 2009).

2.2.1. Freire’s Pedagogy

2.2.2. Ecopedagogies as Critical Pedagogies

Ecopedagogy is grounded in action-orientated teaching through democratic dialogue to better understand how environmental ills oppress people, societies, populations and everything on the planet… It leads to questions regarding whether economics, especially within capitalistic and/or neoliberal frameworks, really does satisfy human needs or give pleasure or whether it separates our needs from the rest of nature.

Changing our beliefs about what constitutes virtue and happiness brings with it a unified motivational response that shapes our actions directly. Hence, coming to believe that virtuous action (and the happy life) involves acting in an environmentally responsible way carries with it motivational change, which feeds directly into the actions we take.

The fact is no man can think for another, any more than he can eat or drink for him.

3. Working towards the UN’s Vision of a Global Education

3.1. The Role of Critical Virtue Education in Social Transformation

Many people are brought up to be virtuous in narrow patterns and persist in thinking in ways still coloured by those patterns. [This is not helped by the fact that we are] unable, individually, to do anything effective or to make any impact on what we, and future generations will, consider to be or reject as compromised virtue.

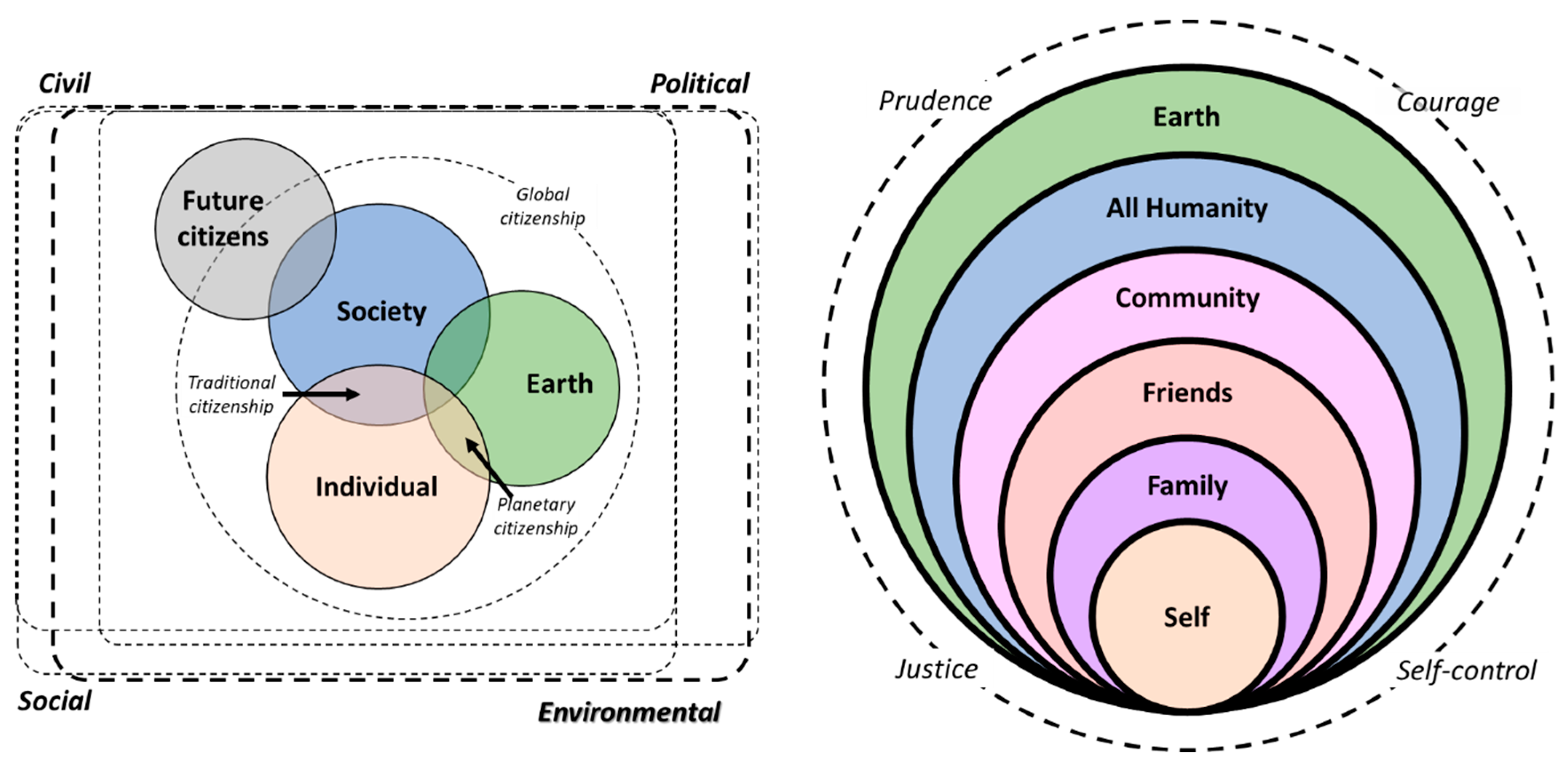

3.2. Education for Global Citizenship

4. Concluding Comment

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hung, R. A critique of Confucian learning: On learners and knowledge. Educ. Philos. Theory 2016, 48, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogia do Oprimido, 17th ed.; Paz E Terra: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Nouri, A.; Sajjadi, S.M. Emancipatory Pedagogy in Practice: Aims, Principles and Curriculum Orientation. Int. J. Crit. Pedagogy 2014, 5, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Pizzolato, N.; Holst, J.D. Antonio Gramsci: A Pedagogy to Change the World; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 5, ISBN 3-319-40447-4. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, C.A. First Freire: Early Writings in Social Justice Education; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 0-8077-5533-8. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, C.A. Globalizations and Education: Collected Essays on Class, Race, Gender, and the State; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 0-8077-4938-9. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, P. Che Guevara, Paulo Freire, and the Pedagogy of Revolution; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000; ISBN 0-7425-7302-8. [Google Scholar]

- Apple, M.W. Educating the “Right” Way: Markets, Standards, God, and Inequality; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 0-415-95271-9. [Google Scholar]

- Apple, M.W. Ideology and Curriculum, 2nd ed.; Routledge Kegen Paul: London, UK; Boston, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Darder, A. Reinventing Paulo Freire a Pedagogy of Love; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gadotti, M. What we need to learn to save the planet. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 2, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadotti, M. Education for sustainability: A critical contribution to the Decade of Education for Sustainable development. Green Theory Prax. J. Ecopedag. 2008, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadotti, M.; Torres, C.A. Paulo Freire: Education for development. Dev. Chang. 2009, 40, 1255–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiaszek, G.W. Educating the Global Environmental Citizen: Understanding Ecopedagogy in Local and Global Contexts; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 1-351-79073-0. [Google Scholar]

- Misiaszek, G.W.; Torres, C. Ecopedagogy: The missing chapter of Pedagogy of the Oppressed (forthcoming). In Wiley Handbook of Paulo Freire; Torres, C., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, R. Critical Pedagogy, Ecoliteracy, & Planetary Crisis: The Ecopedagogy Movement; Peter Lang: Bern, Switzerland, 2010; Volume 359. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Priority #3: Foster Global Citizenship. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/gefi/priorities/global-citizenship/ (accessed on 10 June 2018).

- UNESCO. About the Global Education First Initiative. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/gefi/about/ (accessed on 10 June 2018).

- Misiaszek, G.W. Ecopedagogy and Citizenship in the Age of Globalisation: Connections between environmental and global citizenship education to save the planet. Eur. J. Educ. 2015, 50, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harari, Y.N. 21 Lessons for the 21st Century; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 1-4735-5471-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, R.R. The Stoic and Education. J. Thought 1967, 2, 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, R.R. The Education of Man. J. Thought 1973, 8, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Annas, J. Intelligent Virtue; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; ISBN 0-19-922878-7. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, R.B. The Common Good; Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 0-525-52049-X. [Google Scholar]

- Sison, A.J.G.; Ferrero, I.; Guitián, G. Business Ethics: A Virtue Ethics and Common Good Approach; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 1-315-27783-2. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, W.O. Stoic Ethics: Epictetus and Happiness as Freedom; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2007; Volume 1, ISBN 0-8264-9608-3. [Google Scholar]

- Bevan, E.R. Stoics and Sceptics Four Lectures Delivered in Oxford during Hilary Term 1913 for the Common University Fund; The Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1913. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, T.H. Virtue, praise and success: Stoic responses to Aristotle. Monist 1990, 73, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, D. Stoicism, Moral Education and Material Goods; University of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting, K.; Konstantakos, L.; Carrasco, A.; Carmona, L.G. Sustainable Development, Wellbeing and Material Consumption: A Stoic Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: “Our Common Future”; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sellars, J. Stoic cosmopolitanism and Zeno’s republic. Hist. Political Thought 2007, 28, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting, K.; Konstantakos, L.; Sadler, G.; Gill, C. Were Neanderthals Rational? A Stoic Approach. Humanities 2018, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A.A.; Sedley, D.N. The Hellenistic Philosophers: Volume 1, Translations of the Principal Sources with Philosophical Commentary; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987; ISBN 1-139-64289-8. [Google Scholar]

- Raworth, K. Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist; Chelsea Green Publishing: Hartford, VT, USA, 2017; ISBN 1-60358-674-1. [Google Scholar]

- Misiaszek, G.W.; Misiaszek, L.I. Global citizenship education and ecopedagogy at the intersections: Asian perspectives in comparison. Asian J. Educ. 2016, 17, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, L.G.; Whiting, K.; Carrasco, A.; Sousa, T.; Domingos, T. Material Services with Both Eyes Wide Open. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, M.A. Why ‘Social Justice Warriors’ Are the True Defenders of Free Speech and Open Debate. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/made-by-history/wp/2018/01/09/why-social-justice-warriors-are-the-true-defenders-of-free-speech-and-open-debate/?utm_term=.959743e890b0 (accessed on 10 June 2018).

- Becker, L.C. A New Stoicism; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2017; ISBN 1-4008-8838-7. [Google Scholar]

- Holowchak, M.A. Education as Training for Life: Stoic teachers as physicians of the soul. Educ. Philos. Theory 2009, 41, 166–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, J. An Essay on the Unity of Stoic Philosophy; Munkesgaard: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, G. The Stoic Theory of Knowledge; The Queen’s University: Belfast, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Boudry, M.; Pigliucci, M. Science Unlimited? The Challenges of Scientism; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018; ISBN 0-226-49828-X. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, A. Recognising women in environmental education pedagogy and research: Toward an ecofeminist poststructuralist perspective. Environ. Educ. Res. 1999, 5, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, P. Gramsci, Hegemony and Educational Politics. In Antonio Gramsci: A Pedagogy to Change the World; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- McLaren, P. Seeds of resistance: Towards a revolutionary critical ecopedagogy. Soc. Stud. 2013, 9, 84–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, R. Education and social transformation. Eur. J. Educ. 2015, 50, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Seabury Press: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of Indignation; Paradigm Publisher: Boulder, CO, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of Freedom: Ethics, Democracy, and Civic Courage; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Heart; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of Hope; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 1992; Volume 98. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P.; Macedo, D.P. Letters to Cristina: Reflections on My Life and Work, Trans. Donaldo Macedo, with Quilda Macedo and Alexandre Oliveira; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Misiaszek, G. Engaging Gender and Freire: From Discoursal Vigilance to Concrete Possibilities for Inclusion (Forthcoming). In The Wiley Handbook on Paulo Freire; Torres, C., Ed.; Wiley: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Au, W.W.; Apple, M.W. Reviewing policy: Freire, critical education, and the environmental crisis. Educ. Policy 2007, 21, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez Velasco, J.C. Paulo Freire: Praxis de la utopía y la Esperanza; Universidad de Colima: Colima, Mexico, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rojo Ustaritz, A. Utopía Freireana. La Construcción del Inédito Viable. Perfiles Educ. 1996. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=13207402 (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Geddes, P. The Evolution of Cities. Br. Archit. 1874–1919 1915. Available online: http://habitat.aq.upm.es/boletin/n45/aerec.en.html (accessed on 19 December 2018).

- Smith, T.E.; Knapp, C.E. Sourcebook of Experiential Education: Key Thinkers and Their Contributions; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 1-136-88145-X. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, C.A. Paulo Freire, education, and transformative social justice learning. In Critique and Utopia: New Developments in the Sociology of Education in the Twenty-First Century; Torres, C.A., Teodoro, A., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 155–162. ISBN 0-7425-7580-2. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th ed.; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Teodoro, A.; Torres, C. Introduction. In Critique and Utopia: New Developments in the Sociology of Education in the Twenty-First Century; Torres, C.A., Teodoro, A., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2007; ISBN 0-7425-7580-2. [Google Scholar]

- Illich, I. Deschooling Society, 1st ed.; Harper Colophon: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Joshee, R. Multicultural education policy in Canada: Competing ideologies, interconnected discourses. In The Routledge International Companion to Multicultural Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Misiaszek, G.W. Ecopedagogy as an element of citizenship education: The dialectic of global/local spheres of citizenship and critical environmental pedagogies. Int. Rev. Educ. 2016, 62, 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, D.W. Why Care for Nature? In Search of an Ethical Framework for Environmental Responsibility and Education; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2006; Volume 9, ISBN 1-4020-5003-8. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, C. “Stoicism and the Environment” by Chris Gill. Available online: http://modernstoicism.com/stoicism-and-the-environment-by-chris-gill/ (accessed on 11 November 2017).

- Gadotti, M. Pedagogia da Terra: Ecopedagogia e Educação Sustentável; Fundação Peirópolis: São Paulo, Brazil, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, F.; Prado, C. Ecopedagogia e Cidadania Planetária; Instituto Paulo Freire: São Paulo, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gadotti, M. Education for Sustainable Development: What We Need to Learn to Save the Planet; Instituto Paulo Freire: Sâo Paulo, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Algra, K. Stoic theology. In The Cambridge Companion to the Stoics; Inwood, B., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hegel, G.W.F.; Wallace, W. Hegel’s Logic: Being Part One of the Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1830); Clarendon Press: Gloucestershire, UK, 1975; ISBN 978-0-19-824512-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kerafit, S. 67: Taking Stoicism Beyond the Self with Kai Whiting. In The Sunday Stoic Podcast; Available online: https://itunes.apple.com/us/podcast/the-sunday-stoic-podcast/id1223800559?mt=2 (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Sherman, R.R. Democracy, Stoicism, and Education an Essay in the History of Freedom and Reason; University of Florida Press: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- King, C. Musonius Rufus: Lectures and Sayings; CreateSpace: Seattle, WA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Berges, S.; Coffee, A. The Social and Political Philosophy of Mary Wollstonecraft; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; ISBN 0-19-876684-X. [Google Scholar]

- Botting, E.H. Wollstonecraft, Mill, and Women’s Human Rights; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2016; ISBN 0-300-18616-9. [Google Scholar]

- Zaw, S.K. The reasonable heart: Mary Wollstonecraft’s view of the relation between reason and feeling in morality, moral psychology, and moral development. Hypatia 1998, 13, 78–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollstonecraft, M. A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in a Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke, Occasioned by His Reflections of the Revolution in France; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1790. [Google Scholar]

- Wollstonecraft, M. Vindication of the Rights of Woman; Broadview Press: Peterborough, ON, Canada, 1972; Volume 29, ISBN 1-61536-297-5. [Google Scholar]

- Fourier, C. Degradation of Women in Civilization. Available online: http://womhist.alexanderstreet.com/awrm/doc2b.htm (accessed on 20 August 2018).

- Ashford, N.A. Major challenges to engineering education for sustainable development: What has to change to make it creative, effective, and acceptable to the established disciplines? Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2004, 5, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latremouille, J.; Grant, K.; Kalu, F.; Dodsworth, D.; Cockett, P.K.; Mitchell-Pellett, M.-A.; Paul, J. Reimagining Teacher Education through Design Thinking Principles: Curriculum in the Key of Life. J. Can. Assoc. Curric. Stud. 2015, 13, 88–112. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C.S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success; Random House Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 1-4000-6275-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sher, M.; King, S. What Role, if any, Can Education Systems Play in Fostering Social Transformation for Social Justice? Prospects, Challenges and Limitations. Eur. J. Educ. 2015, 50, 250–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuckett, A. Adult education, social transformation and the pursuit of social justice. Eur. J. Educ. 2015, 50, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M. Capabilities as fundamental entitlements: Sen and social justice. Fem. Econ. 2003, 9, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, N. Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach and Education: Enhancing Social Justice. E-J. Lit. Hist. Ideas Images Soc. Engl. Speak. World 2016. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/lisa/8913 (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Saito, M. Amartya Sen’s capability approach to education: A critical exploration. J. Philos. Educ. 2003, 37, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Well-being, agency and freedom: The Dewey lectures 1984. J. Philos. 1985, 82, 169–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williford, M. Bentham on the Rights of Women. J. Hist. Ideas 1975, 36, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, A. Aporofobia, el Rechazo al Pobre. Un Desafío para la Democracia; Paidós: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, C. Preface. In Educating the Global Environmental Citizen: Understanding Ecopedagogy in Local and Global Contexts; Misiaszek, G.W., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 1-351-79073-0. [Google Scholar]

- Whiting, K.; Konstantakos, L. Taking Stoicism beyond the Self: The Power to Change Society. Available online: https://dailystoic.com/stoicism-beyond-the-self/ (accessed on 13 August 2018).

- Turner, J. As Origens, o Nascimento, a Evolução de uma Ideia. XXI 2017, 8, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M. Patriotism and cosmopolitanism. In Twentieth Century Political Theory: A Reader; Bronner, S.E., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 159–168. ISBN 0-415-94898-3. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, C.A. Global citizenship and global universities. The age of global interdependence and cosmopolitanism. Eur. J. Educ. 2015, 50, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, C. The Stoics on humans, animals and nature. Unpublished work.

- Soysal, Y.N. Limits of Citizenship: Migrants and Postnational Membership in Europe; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1994; ISBN 0-226-76842-2. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, C.A. Democracy, education, and multiculturalism: Dilemmas of citizenship in a global world. Comp. Educ. Rev. 1998, 42, 421–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, N. This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 1-4516-9739-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gadotti, M. Pedagogy of Praxis: A Dialectical Philosophy of Education; Suny Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1996; ISBN 1-4384-0360-7. [Google Scholar]

- Apple, M.W.; Au, W.; Gandin, L.A. Mapping critical education. In The Routledge International Handbook of Critical Education; Apple, M., Au, W., Gandin, L.A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 13–30. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Whiting, K.; Konstantakos, L.; Misiaszek, G.; Simpson, E.; Carmona, L.G. Education for the Sustainable Global Citizen: What Can We Learn from Stoic Philosophy and Freirean Environmental Pedagogies? Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040204

Whiting K, Konstantakos L, Misiaszek G, Simpson E, Carmona LG. Education for the Sustainable Global Citizen: What Can We Learn from Stoic Philosophy and Freirean Environmental Pedagogies? Education Sciences. 2018; 8(4):204. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040204

Chicago/Turabian StyleWhiting, Kai, Leonidas Konstantakos, Greg Misiaszek, Edward Simpson, and Luis Gabriel Carmona. 2018. "Education for the Sustainable Global Citizen: What Can We Learn from Stoic Philosophy and Freirean Environmental Pedagogies?" Education Sciences 8, no. 4: 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040204

APA StyleWhiting, K., Konstantakos, L., Misiaszek, G., Simpson, E., & Carmona, L. G. (2018). Education for the Sustainable Global Citizen: What Can We Learn from Stoic Philosophy and Freirean Environmental Pedagogies? Education Sciences, 8(4), 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040204