Abstract

This paper discusses the diffusion of two models of mobile learning within the educational research literature: The Framework for the Rational Analysis of Mobile Learning (FRAME) model and the 3-Level Evaluation Framework (3-LEF). The main purpose is to analyse how the two models, now over 10 years old, have been referenced in the literature and applied in research. The authors conducted a systematic review of publications that referenced the seminal papers that originally introduced the models. The research team summarized the publications by recording the abstracts and documenting how the models were cited, described, interpreted, selected, rejected, and/or modified. The summaries were then coded according to criteria such as fields of study, reasons for use, criticisms and modifications. In total, 208 publications referencing the FRAME model and 97 publications referencing the 3-LEF were included. Of these, 55 publications applied the FRAME model and 10 applied the 3-LEF in research projects. The paper concludes that these two models/frameworks were likely chosen for reasons other than philosophical commensurability. Additional studies of the uptake of other mobile learning models is recommended in order to develop an understanding of how mobile learning, as a field, is progressing theoretically.

1. Introduction

Mobile learning came into focus in the 1990s as personal digital assistants (PDAs) and, later, mobile phones began to facilitate learning [1]. In 2005, m-learning became an accepted term [1], although the definition of the term remained problematic. Within this relatively short time span, researchers and practitioners have grappled with defining, understanding, designing, applying, and evaluating mobile learning. They question who and what is mobile as well as how to integrate mobile tools into pedagogical practices. Conceptual models and frameworks play a significant role in answering these questions because they explain “either graphically or in narrative form, the main things to be studied—the key factors, concepts, or variables—and the presumed relationships among them” [2]. Evaluation models are also significant tools; they can be formative (information about the mobile intervention/tool is fed back to the researchers for improvement during the learning experience), summative (information is used to judge the usefulness of the intervention/tool after the learning experience), or both [3].

The purpose of this paper is to examine the uptake of two m-learning frameworks: Koole’s Framework for the Rational Analysis of Mobile Learning (FRAME) conceptual framework [4,5] and Vavoula and Sharples’ 3-level evaluation framework (3-LEF) as designed for the MyArt Space project [6,7]. A preliminary examination of citation numbers in Google Scholar suggests that both models have been referenced extensively. As of writing this paper, the number of Google Scholar citations for the FRAME model [4,5] is over 500; the number for the 3-LEF [6,7] is over 300. Upon closer examination, these numbers are somewhat misleading because they include any kind of reference—even references that appear in reference lists without having cited the original papers within the body text. Furthermore, the numbers from sources such as Google Scholar and other common indices fail to provide information about how the models have been used, if they have been understood and/or interpreted accurately, if they have offered a springboard to innovation in mobile learning, or if they have stimulated the emergence of other models.

A closer examination of how and why models proliferate through the field of mobile learning (and beyond) may help us gain a sense of the assumptions and perspectives of the researchers who have referenced the models. A general criticism of the field of educational technology is that there is insufficient evidence of critical thinking in the development of new perspectives, paradigms, methodologies, and reflective practice [8]. According to Yanchar, Gibbons, Gabbitas, and Matthews [8], critical thinking refers to “a cloud of intellectual processes by which ideas and processes are formulated, expressed, examined, questioned, tested, proven, discussed, and used within a field.” So, if authors have selected or rejected a model, did they have any underlying philosophical, practical, or operational reasons? If researchers fail to base their selection upon critically-thought-out criteria, what are the implications for the field? How can we determine “the conditions for progress” in the field [9]?

In order to examine the uptake of the FRAME and 3-LEF, the researchers conducted a systematic review of publications that cited the seminal articles in which Koole, Vavoula, and Sharples introduced their frameworks. The publications were summarized, the reference and citation information were documented, the abstracts were recorded, and any specific comments pertaining to the frameworks were recorded. These notes were then coded according to a list of criteria such as fields of study and/or researchers that have cited the models and their reasons for adoption or rejection.

This paper will first describe the two models. Then, the authors will explain the rationale for the study. The methodology section describes the databases, search terms, inclusion criteria, and exclusion criteria. The results section provides both numeric data of the included publications (number, types, geographic reach, topics of research, and research methods) and qualitative data (on reasons for use, critiques, and modifications of the models). The paper concludes by noting that there is need to trace the diffusion of theoretical models in order to understand the extent to which epistemological and ontological positions are guiding research in mobile learning, and more broadly, educational technology.

2. The Models

As mentioned above, the primary articles in which the models were introduced were published in between 2006 and 2009 [4,5,6,7]. These two models were chosen because they were developed and published at approximately the same time. These models are also over 10 years old; therefore, sufficient time has elapsed, and our research team can trace referencing patterns. These two models were also selected because the researchers are most familiar with them, which helped the team examine how the models were being used and (mis-)understood. Although, both the FRAME and the 3-LEF can be used outside of mobile learning, they can be applied to other educational technologies (including non-digital technologies). The 3-LEF is specifically an evaluative framework that outlines phases in the evaluation process. The FRAME can be used in an evaluative way, but it is more of a conceptual model in that it aids in the conceptualization of how phenomena are articulated.

2.1. The FRAME Model

The FRAME model was developed for a master’s thesis [4] at a time when mobile learning was first entering the mainstream of educational research. The purpose of the thesis was to examine key characteristics of a collection of mobile devices within the context of distance education at the post-secondary level. The study began in 2004 when few other mobile-learning models and frameworks were available. The master’s thesis was made available online in 2006. A chapter was published in 2009 in a free, open-access book, which likely aided in the proliferation of the model worldwide [10]; this open-access chapter is the document that is primarily referenced in the literature.

Originally, Koole worked primarily within a constructivist perspective, but also drew upon cognitivist theories (such as [11,12,13,14]). Special interest was placed upon situated learning (such as [15,16]), human-computer interaction (such as [17,18,19]), and classics in distance education (such as [20,21]). Koole has since moved to a sociomaterialist view of the FRAME model [22], which takes an ontological perspective in which the human and the material are equally important.

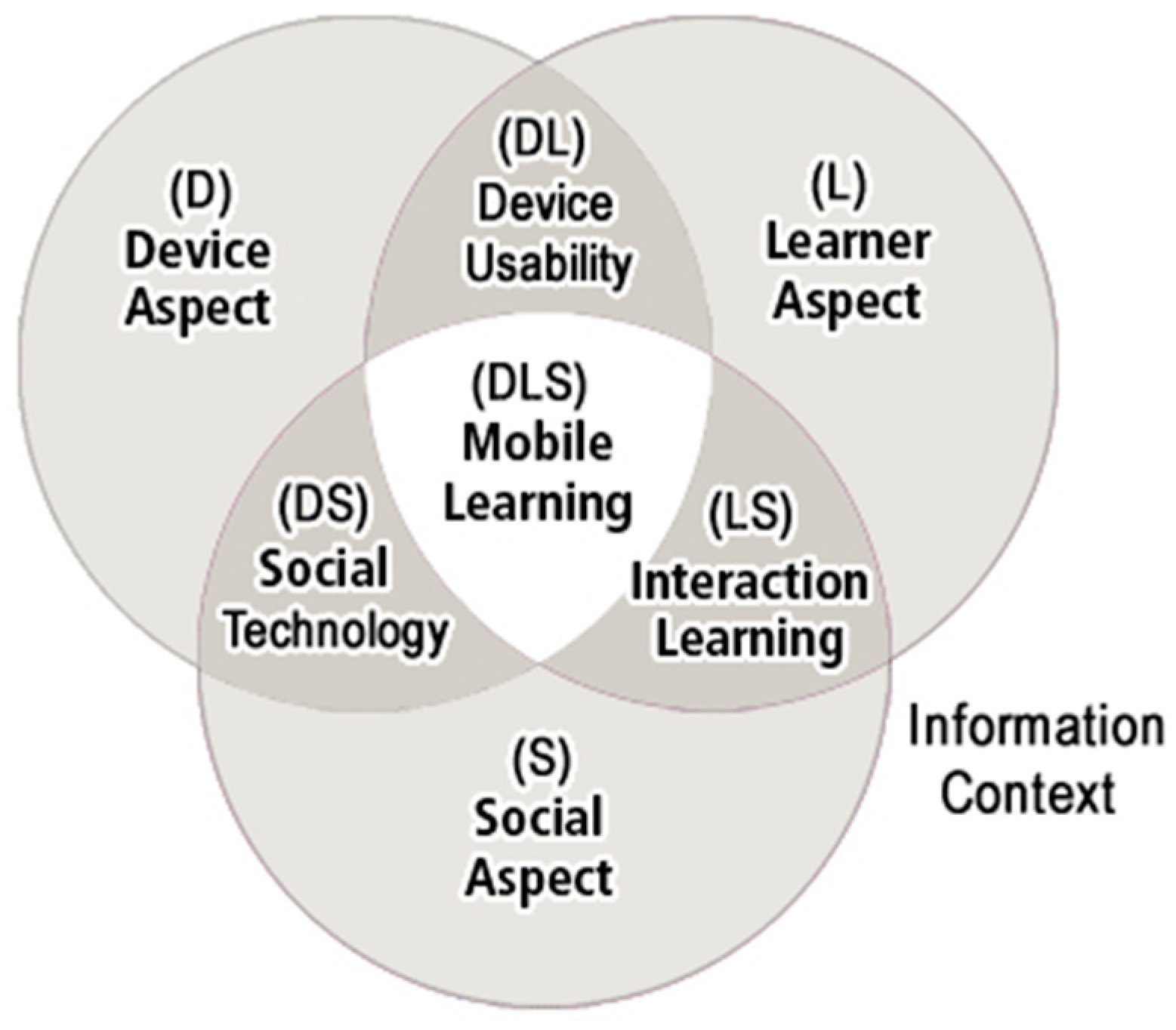

The FRAME Venn diagram depicts the three main aspects that influence and co-produce mobile learning (Figure 1). Within a researcher-delimited context, the key aspects of the FRAME model comprise the device, learner, and social aspects. The FRAME model requires a basic understanding of set theory, a branch of mathematical logic. In a Venn diagram, no one part is more or less important than any other. In the FRAME model, each circle is the same size symbolizing that they are equally important. Even the center of the circle (which is labelled “mobile learning:) is no more or less important than the parts that come together to create it nor is any other part of the diagram more important than the context within which it is situated (the “information context”). The reason the Venn diagram was used was to depict the pieces that come together co-construct the phenomenon of mobile learning. Logically, then, it is not possible to suggest that the FRAME model is device-centric, technologically determinist, or socially determinist. Similar to a jigsaw puzzle, all the pieces are necessary to create the finished picture, but no piece is more important than any other. The whole is just as important as the parts.

Figure 1.

The Framework for the Rational Analysis of Mobile Learning (FRAME) model.

The device, learner, and social aspects overlap with each other creating the interaction-learning, social-technology, and device-usability intersections. The center of the Venn diagram shows the overlapping of all three aspects where mobile learning emerges. The overlapping of the circles guided the development of a list of key questions [5] that designers could use in developing mobile learning environments and interventions. Table 1 summarizes the key (but partial) characteristics of each part of the FRAME model.

Table 1.

Elements of the FRAME Model.

2.2. The 3-Level Evaluation Framework (3-LEF)

The 3-LEF model emerged as research was being done on the Myartspace project [7]. Myartspace was a project in which mobile phones were used by children on a field trip to a museum. Using their phones, learners could collect information and send it to a website. The students could view, share and present the information they gathered; in this way, they could digitally connect their field trip artifacts to their classroom and home environments. Pedagogically, the project involved an inquiry learning approach in which the learners would formulate their own questions, design their own plans, and determine what they learned.

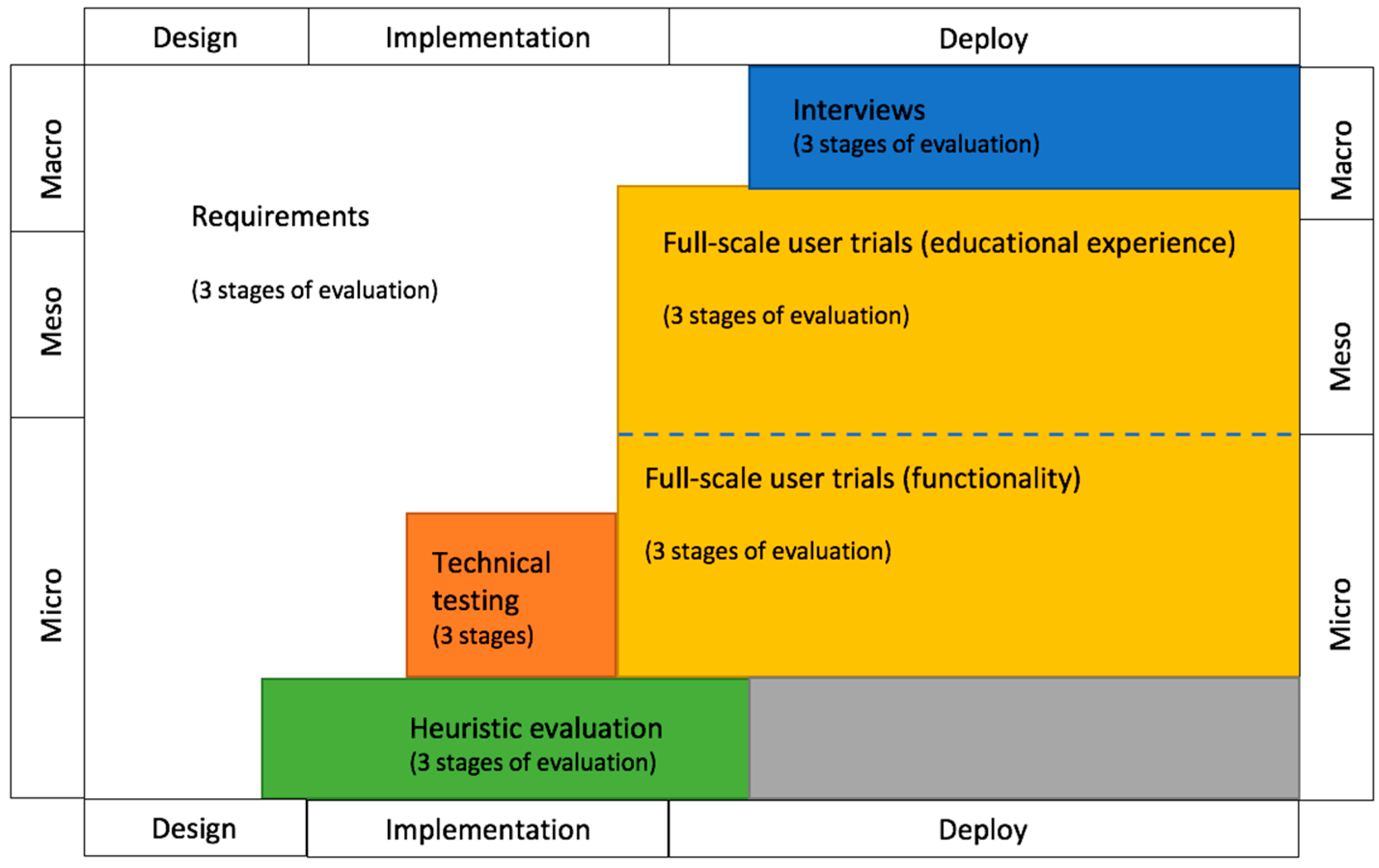

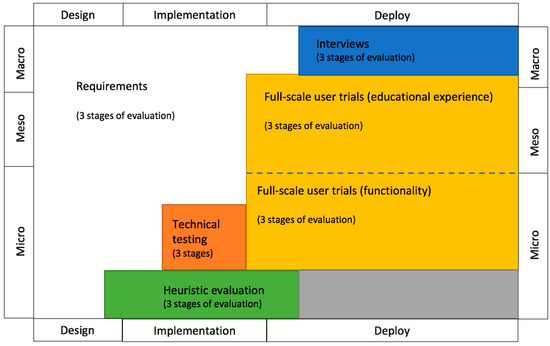

The potential and effectiveness of project was evaluated using the 3-LEF. Whilst maintaining a focus on the socio-cultural context of learning [6], the framework is highly structured and is based upon Meek’s “lifecycle approach” [23]. The lifecycle approach was originally developed for a PhD dissertation in the field of software engineering. In this approach, evaluation occurs through the processes of conception, requirements analysis, design, implementation and deployment. The 3-LEF is sometimes referred to as the 3M framework because it comprises three levels: micro, meso, and macro. The micro level concerns the actual behaviours, interactions, and activities of the users. The meso level examines patterns in learning experiences across individuals and focuses on critical incidents—inclusive of both “breakthroughs and breakdowns” [6]. To identify gaps between what is expected and what actually occurs, the data collection occurs in three stages. Stage one involves collecting information through interviews with users and document analysis regarding expected and desired behaviours (of students and tools). In stage two, the researchers collect data through live observation or audio/video recordings, about what actually occurred. And, finally, in stage three, the researchers conduct reflective interviews with the users and analyse the data collected in stages one and two. To summarize, the 3-LEF combines three processes.

- Development process phases: requirements analysis, design, implementation, and deployment.

- Levels of granularity: micro, meso, and macro.

- Stages of data collection and analysis: stage 1 documentation of expectations, stage 2 documentation of actual activities, and stage 3 of gap analysis.

In order to help visualize the process, the authors provide an analysis-and-evaluation diagram (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The 3-Level Evaluation Framework (3-LEF) evaluation and analysis process [7].

The original and more detailed version of Figure 2 appears in the Myartspace article [7]. Although the Myartspace article provides an example of how the framework was applied, the article on “meeting the challenges” [6] is more cited in the literature. The article [6] outlines six challenges in evaluating mobile learning, introduces the 3-LEF, how the framework was applied to the Myartspace project, and discusses how the six challenges were address through application of the 3-LEF.

2.3. Brief Comparison of the Two Models

Table 2 provides a summary of the main steps as originally intended by the authors of the FRAME and the 3-LEF models. (As will be discussed later, the models have been used in ways unpredicted by the authors.)

Table 2.

Summary of the main features of both models (FRAME and 3-LEF).

3. Motivation and Rationale for the Study

In their review of models and frameworks for designing mobile learning experiences and environments, Hsu and Ching [24] documented and categorized 17 notable models published between 2007 and 2015. (For the purposes of this paper, the terms model (conceptual model) and framework are used interchangeably. The differences between models and frameworks are outside the scope of this study.) A simple Google search will reveal that there are far more than 17; an exhaustive list needs yet to be compiled and published. Noting the proliferation of models and frameworks in the field of mobile learning, our research team began to question how existing models are being selected, extended, and/or rejected. We hoped that exploring the implementation and/or critiques of current models facilitate our understanding of how and why new models continue to emerge. Ultimately, what tools do mobile learning researchers require in order to answer their research questions? For these reasons, the main goals of this paper are to

- determine the number of references to the model/framework;

- examine the geographic and temporal reach of the model/framework;

- determine the number of times the model/framework has been used to guide research projects;

- locate the reasons why the model/framework was chosen;

- locate and analyse critiques of the model/framework (i.e., why the model/framework was rejected); and

- examine how the model/framework may have been modified.

4. Research Questions

Based on the aforementioned rationale and goals, the primary research questions are

- How have the seminal articles introducing the FRAME model and the 3-LEF been referenced in the education literature (including but not limited to the field of mobile learning)?

- How has the FRAME/3-LEF been used within the field of education?

5. Research Methodology

The research team for this project searched for any publication that cited the original (“seminal”) articles introducing the FRAME model [4,5] and the 3-LEF [6,7], which were published since June 2006 and May 2018. The inclusion criteria were broad because our team was interested in the range of study designs, subject areas, and geographic range in which the models have been used. The publications included spanned those that referred to the seminal articles only in passing to those that discussed and/or applied the model/framework in depth. Publications were rejected if they made no substantive comments about the seminal articles or the model/framework (failed to cite the seminal articles within the body text). We excluded articles by Koole, Sharples, and Vavoula in which they self-cited the introductory articles.

Each member of the research team received training from a research librarian on selecting the databases and formulating search strings. The following databases and search mechanisms were accessed:

- Eric;

- USearch;

- Proquest;

- Web of Science;

- Google Scholar;

- Research Gate;

- Academia.edu;

- Google search engine.

Because the search was so specific, the list of key words was kept simple. Table 3 lists the key words used in the database searches.

Table 3.

Keywords used in database searches.

The author names were necessary in all searches; otherwise, the number of results returned was overwhelming. For example, without “Koole” in a search for FRAME model, the results yielded were in excess of 17,000. Similarly, “Vavoula” and “Sharples” were used in all the searches for the 3-LEF.

As the publications were located, they were summarized, the reference and citation information were documented, the abstracts were recorded, and any specific comments pertaining to the frameworks were documented. Table 4 lists the information documented for each paper located.

Table 4.

Template for summarizing publications.

The summaries were then coded in Nvivo according to a list of criteria (a priori coding) such as fields of study, and/or researchers that have cited the models and their reasons for adoption or rejection. (See Appendix A for a complete list of codes/nodes).

The “applied” code was important in allowing the researchers to run queries in Nvivo separating those studies in which the FRAME or 3-LEF were applied in research. This helped the research team to determine the extent to which the seminal articles were merely cited (code: “literature review”) in contrast to the number of times the model/framework was actually used.

6. Results

6.1. Number of Publications Included in the Study

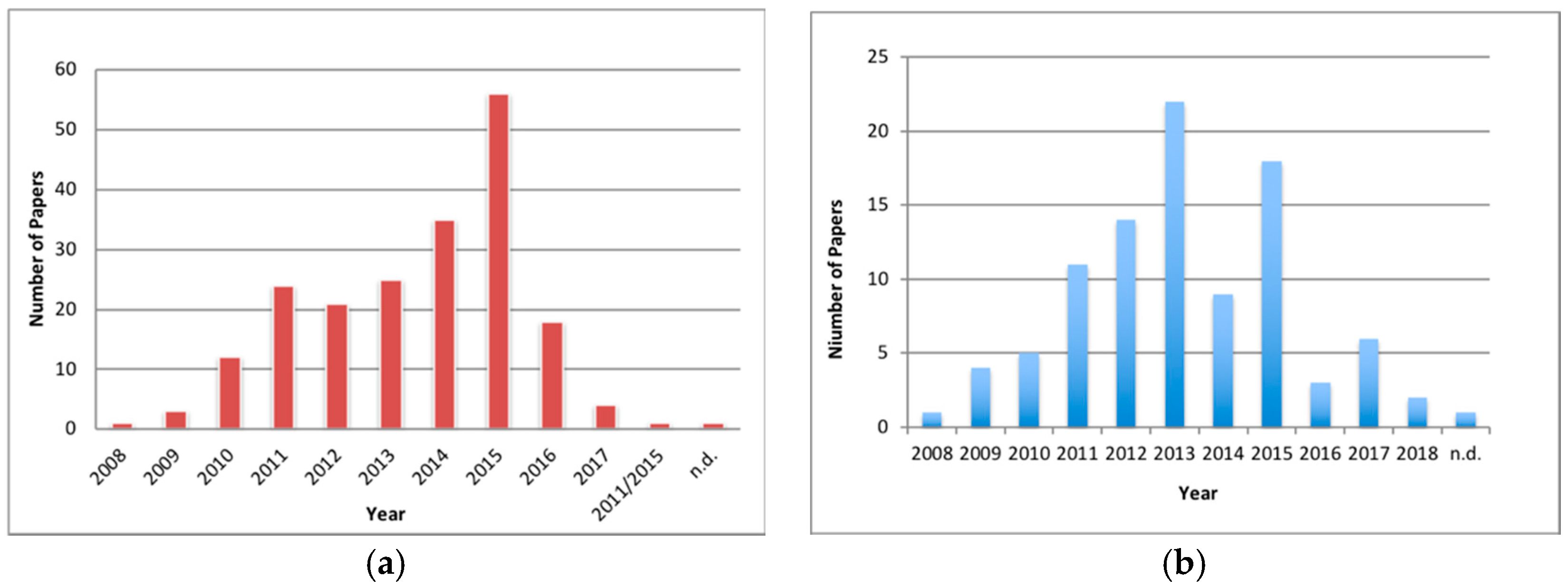

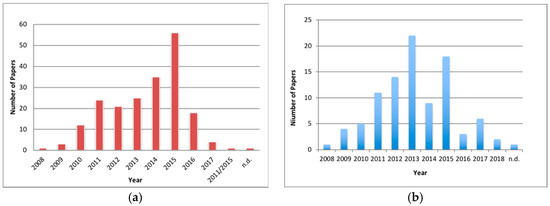

In total, 208 publications cited the FRAME model and 97 publications cited the 3-LEF. As can be seen in Figure 3, the FRAME model experienced its highest uptake in 2015. The 3-LEF diagram shows 2013 and 2015 as its years of highest uptake.

Figure 3.

Number of publications referencing the (a) FRAME model and (b) 3-LEF, by publication date.

6.2. Types of Publications

The majority of the papers were published in journals followed by conference papers (Table 5). Both the 3-LEF and FRAME model were also mentioned in a significant number of dissertations and master’s theses.

Table 5.

Publication types.

6.3. Geographic Reach

Our team was interested in geographic reach; that is, to what extent researchers in other countries are aware of the 3-LEF and the FRAME model. For each paper, we considered the location of each author (i.e., where s/he works) and, if indicated, the country in which the research was conducted. Table 6 shows the number of countries (authors’ location and country of research) for all publications and the number of countries (authors’ location and country of research) for those publications in which the FRAME or 3-LEF was applied.

Table 6.

Number of countries.

6.4. Areas of Research

The 3-LEF and the FRAME model were referenced within publications belonging to a variety of fields and contexts. During this project, our team documented whenever the authors of the papers indicated areas of their research. We collapsed the areas into five major categories:

- Education levels;

- School subjects;

- Learning activities and skills development;

- Uptake, support, design of mobile systems; and

- Issues, challenges, and potentials of mobile learning.

Appendix B lists the areas of research within the five categories. It appears that the greatest number of studies were in the area of higher education. Within the learning activities category, gamification, contextual learning, field trips, and the use of social networks are the greatest in number. There was a wide variety of school subject areas across all the publications, but language learning and health-related subjects were very strongly represented. In the uptake, design, and support category, studies of learner uptake, attitudes, and support were most numerous, followed by the design and evaluation of learning environments and studies of pedagogical practices.

6.5. Research Methods and Methodologies

Table 7 lists the methods and methodologies using the nomenclature of the original authors for all studies and only those that applied the FRAME model and 3-LEF in their research.

Table 7.

Methods and methodologies as named by the authors.

6.6. Contributions of the Seminal Articles

As our research team read through the publications that cited the 3-LEF, we began to note some patterns in how the seminal articles were being referenced. As such, it became clear that the works that initially introduced the FRAME model and 3-LEF contributed to the field in more general ways—that is, outside of evaluation and conceptual work. In the following section, the numbers in the tables offer a sense of proportion of the topics mentioned.

6.6.1. FRAME Model Comments in the Literature

Out of 65 references (outside of papers that explicitly used the model in their research), 42 publications made minor references to the FRAME model. Of those that more explicitly cited the two seminal articles [4,5], Table 8 summarizes the topics that were the most mentioned.

Table 8.

Most referenced topics (n = 65).

We observed that many authors were attracted by the notion that mobile learning comprises multiple aspects. At the same time, some authors focused their research on a particular aspect such as the social. Others made explicit reference to technological characteristics of mobile devices.

6.6.2. 3-LEF Comments in the Literature

We coded 59 instances of authors citing the two seminal articles on the 3-LEF [6,7]. Of these, we coded 35 comments as minor mentions. Table 9 summarizes the topics that were the most mentioned.

Table 9.

Most referenced topics (n = 59).

Vavoula and Sharples’ work was very often mentioned in a list of examples of evaluation (12 instances) studies in mobile learning. There were 11 instances where researchers explicitly argued for additional evaluation studies. There were four incidents in which the authors referred to the 3-LEF articles in order to clarify definitions such as mobile learning, location-based learning, and microsites. Six authors explicitly mentioned the micro, meso, and macro perspectives. Authors also drew upon the 3-LEF publications to champion the view that mobile learning is primarily a social rather than a technological phenomenon.

6.7. Reasons for Use

Our team searched for statements that explicitly stated why the researchers chose to use the model/framework to conduct their research.

6.7.1. Reasons for Using the FRAME Model

Seven of the eleven references coded for “reasons for use” indicated that the main appeal of the FRAME model is that is gives equal footing to the learner, the social and the technological aspects of mobile learning [25,26]. One author suggested that the model not only outlines the relationship between the three aspects but also addresses contemporary pedagogical issues of information overload, knowledge navigation, and collaborative learning [27]. Another work found that the choice of what to evaluate was alleviated, as all three aspects are equally important and should, therefore, all be evaluated [28]. Sandpearl [29] comments that maximum learning potential is achieved when the interactions between the social, the device, and learner converge.

Some authors showed interest in the social aspects of mobile learning [30]. Others commented that the FRAME model supports a socio-cultural view of learning [31,32]. Others appreciated the constructivist approach underlying the model and that it is an appropriate tool for examining learning and collaboration [25,26].

Several authors stated that the FRAME model was intuitive and easier to use than other models [26,33]. The accompanying checklist of key items and questions to guide the development of mobile learning applications [5] appears to have contributed to the perceived ease of use [24,34,35].

6.7.2. Reasons for Using the 3-LEF Framework

Three publications provided some insight into why they used the 3-LEF. One suggested that the framework, with the embedded micro, meso, and macro levels, acknowledges the ambiguity in the relationship between learning and the role of the institution [36]. The second indicated that the ability to evaluate at all stages along the development trajectory was key in the choice to adopt the 3-LEF [37]. And, the third paper indicated that the 3-LEF was selected because there were no other models specifically designed for wearable technology (a head-mounted display) [38].

6.8. Critiques of Model/Framework

Critiques of the model/framework were much easier to locate than rationales for their use. Our analysis revealed some astute observations and as well as some misconceptions of the models and the field of mobile learning overall. Although expressing appreciation for the 3-LEF and the FRAME model, some authors suggested that there is a lack of frameworks and models and, of the existing models, none of them are sufficient for guiding the design of mobile learning in varying contexts [35,39].

There were many critiques of mobile learning models in general. In these cases, the FRAME model and/or the 3-LEF were listed amongst other models:

- They have a limited perspective on context as they do not include the role of media at producing learning contexts. No methodologies or tools are available yet that treat the virtualization of context in an explicit way [40].

- They are limited in their practical applicability because they have no defined guidelines that consider the stages for the deployment of m-learning, but they do serve as starting points for the development of a sustainable M-learning model [41]. As such, there is need to bridge the gap between pre- and post-implementation phases in order to ensure sustainability.

- Do not address the question of how best to implement mobile learning in formal education [42].

- These frameworks are not learning theories per se. Rather, they offer ways to evaluate and frame mobile learning activities within the ubiquitous landscape of mobile learning [43]. It was also noted that the models lacked investigation into some macro-level factors including cultural and social barriers. Therefore, some papers highlighted the need for consideration and integration of broader social contexts when examining the efficacy of specific mobile learning contexts and research [44].

6.8.1. Critiques of the FRAME Model

Critiques specifically focusing on the FRAME model referred to missing criteria. Observing that the FRAME model defines mobile learning in terms of the interactions between learners, their devices, and other people [45], Wishart, cautions that Koole’s conceptual model does not acknowledge the potential mobility of the learner whose technology enables them to use information and data from one context to another. Khaddage et al. state that the FRAME model fails to address factors such as policies, pedagogy, technology, and innovative research in the field [46]; therefore, more guidance about how to utilize emerging mobile technologies and integrate them seamlessly into teaching and learning is still needed [46].

Power proposed an instructional-design related model that explicitly guides pedagogical issues [47]. He posited that although the FRAME model presents a holistic picture of the domains to be considered when designing or redesigning mobile learning initiatives, it does not provide guidance on the pedagogical design considerations needed for creating an effective collaborative learning experience for the learner [47].

Some critiques were more general in nature. For example, one paper argued that the FRAME model is a conceptual proposal and, hence, does not explore whether it would be suitable in real scenarios for supporting the development and adoption of its approaches [48]. Another researcher stated that the FRAME model is not yet sufficient given that further understanding of the highly dynamic emerging field of mobile learning is required [49]. Other authors indicated that Koole’s FRAME model is not applicable in primary education because it was “constructed in a higher education context, [which is] quite different from that of primary education” [50].

6.8.2. Critiques of the 3-LEF Model

We coded 11 instances of “critique” amongst the 97 publications. Some authors suggest that there is a general lack of systematic evaluation studies in the field of mobile learning. One paper includes a discussion of the 3-LEF but subsequently claims that the field of mobile learning lacks evaluation models/frameworks that have been “systematically and rigorously applied and fleshed out” [39]. Having listed a number of studies “conceptualizing” mobile learning, one paper indicated that no prior publications had adequately or rigorously measured success, scalability, and replicability of mobile learning initiatives. However, the author(s) offer no specific critiques of the 3-LEF (or other frameworks) were offered [51].

Farley and Murphy suggest that the 3-LEF was overly focused on the social characteristics of mobile learning to the detriment of the technical [39]. Another author praises the 3-LEF for its complex gap analysis and design heuristics but rejects the framework because it does not provide evaluation criteria [52].

Finally, we found an interesting critique of the micro-meso-macro approach: that it would require researchers to switch perspectives during the research project [53]. The authors suggested that perspective switching could result in communication issues and confusion because people working at one level would lack understanding of the impact [of the mobile intervention] on those working at other levels.

6.9. Extensions and Modifications

Our review of the literature revealed that some researchers suggested modifications to the FRAME model and the 3-LEF. Our team also noticed instances in which the FRAME and the 3-LEF were blended with other models.

6.9.1. Modifications to the FRAME Model

Some authors claim to have extended the FRAME model. For example, Norman, Din, and Nordin altered the model so that it would be based on four aspects: web 3.0 technology, learner context-awareness, learner cognition, and learner social skills [54]. Boyinbode, Ng’ambi, and Bagula integrated Anderson’s six types of educational interactions, something that they thought had not been addressed directly in the original FRAME model [55]. Meanwhile, Levene and Seabury combined the FRAME model with Park’s transactional distance theory model in an effort to inform instructional design practices [56].

The relational structure of the FRAME model was also modified. For example, the “augmented FRAME” was designed in order to differentiate K-2 learning methods based on characteristics such as targeted grade level, specific devices, necessary infrastructure, mobility, cost per student, and type of learning [50]. Pani and Mishra offer a modified view in which there are four aspects (social, learner, device, and context) and four intersections (device usability, interaction learning, mobility interaction, and pervasiveness) [57]. Finally, Wong recommended a new mobile learning model where he has embedded a curriculum aspect into the Koole’s FRAME model and places the learner aspect into the center of the FRAME model [27]. He suggests that the curriculum aspect should be evaluated in future research studies to find out how mobile informal learning experiences or activities can assist students in formal learning contexts.

Some authors offered less extensive modifications such as the addition of “mobile pedagogy” considerations that complement the socio-cultural characteristics of the FRAME model [32]. Another author suggested that instead of mobile learning, ubiquitous learning or pervasive learning could occupy the center of the Venn diagram [57]. Lefrere also recommended that the FRAME model include networking and networked services. In this way, researchers would acknowledge the surface functionality of a device as well as the functionality it gains through networking [58].

6.9.2. Modifications to the 3-LEF

There was no evidence of major modifications proposed for the 3-LEF. We documented only one minor modification. In one study, the author(s) examined the micro and meso levels in depth [53]. At the micro level, they added a mobile quality piece to the evaluation.

Our Nvivo code “extends other model” captured some evidence that elements of the 3-LEF were used to enhance other evaluation models/frameworks. In one dissertation, the author combined the 3-LEF with other models in order to create his/her own evaluation criteria [59]. Another study focused on the meso level (learner experience) whilst proposing a new model developed in order to highlight socio-cultural characteristics of mobile learning [32].

7. Discussion

7.1. Number of References

As mentioned, at the time of writing, Google Scholar indicated that the FRAME model had been referenced over 500 times and the 3-LEF over 200 times. Our team searched eight databases for any publications referencing the seminal articles that introduced the models [4,5,6,7]. Our team removed from analysis articles that referenced the seminal articles without actually discussing or citing them in their body text. Our final analysis was left with 208 articles citing the FRAME model and 97 for the 3-LEF.

One of our main goals was to explore the impact that the FRAME model and the 3-LEF have had in educational research. A preliminary look at numeric data in reference indices suggests that both models are well represented in conference presentations and journal articles. Surprisingly, the FRAME model has been mentioned in an unusually high number of doctoral dissertations (see Table 5). Overall, the FRAME model appears to have been more referenced than the 3-LEF. This might be due to the more general, conceptual nature of the FRAME model. It might also be related to the publication of the 2009 article [5] in a free, open-access publication.

7.2. Reasons for Use

As alluded to earlier, the both models were applied in ways that were not originally predicted by the Koole, Vavoula, and Sharples (summarized in Table 2). Although originally designed for qualitative analysis, the FRAME model has been used in quantitative studies in which researchers have attempted to develop numeric measures of mobile characteristics [60,61]. In the case of the 3-LEF, some researchers chose to implement it at only one level of granularity such as the micro or the meso [62,63]. Both of these examples suggest healthy innovation.

Although there were a number of topics that were mentioned in the literature, our team took special note that both the FRAME and the 3-LEF were recognized for emphasizing the social characteristics of learning (See Table 8 and Table 9). We would argue that both models, while having strongly supporting a social view of learning, also place significance on other factors within the mobile learning milieu. To a greater or lesser extent, they both involve examining the physical environment and technology.

Both models recognized the interrelationship of multiple components that are often treated separately in research such as

- The social, learner, and technical aspects;

- The micro, meso, and macro levels;

- The phases of development; and

- The stages of evaluation.

In our analysis, we gained a sense that the multi-components approach was a drawing feature of both the FRAME and the 3-LEF.

7.3. Critiques

Naturally, critiques were often used by authors in order to argue in favour of a new model they were proposing. Models such as the FRAME and 3-LEF were viewed by some as a starting point, but that they were lacking in some ways. Some authors appeared to require evaluation criteria or guidelines that were customized to their study contexts and phenomena such as virtualization of context, in/formal learning situations, and ubiquitous landscapes. Similarly, one paper suggested that neither model allowed for use in formal education settings. However, both the FRAME and the 3-LEF are deliberately designed to accommodate a wide variety of contexts and phenomena. And, the authors of both the FRAME model and the 3-LEF have acknowledged their applicability beyond mobile learning. As one writer correctly observed, they are conceptual/evaluative tools [44]. As such, they were designed with some flexibility and openness permitting customization for specific contexts and phenomena.

The critique that the FRAME and the 3-LEF (1) do not include the role of media in producing learning contexts [40] and (2) that factors such as cultural and social barriers are not considered lacks consistency with our reading of the FRAME model and the 3-LEF. The role of media and social barriers fit neatly within the models. For example, media can be represented in the technology aspect of the FRAME model (see Figure 1) and is embedded throughout the design processes in the 3-LEF (see Figure 2). Furthermore, social barriers can be discussed within the social aspect and the social-interaction intersection of the FRAME model. The 3-LEF was developed within a socio-cultural perspective; therefore, social issues can be examined through the ongoing interviews with users embedded within the evaluation process.

Interestingly, another critique of the 3-LEF was that it is overly focused on the social to the detriment of the technical [50]. If the scope of a research project is to examine only the technological aspects of a mobile learning initiative, then it is logical that the researcher would modify it so as to focus on a particular characteristic.

Finally, there was a criticism that neither model is a learning theory per se. That is true, these models were not designed as learning theories. One would choose to use the FRAME model to gain a conceptual understanding of a mobile learning situation or to guide the design of a mobile learning application. One would use the 3-LEF to evaluate a mobile learning situation or application. Nonetheless, both models were conceptualized and developed within perspectives such as social constructivism, situated-learning, and socio-cultural theories. As we have discovered through this research, both have been applied in the design of learning applications. Therefore, we argue that models can be used creatively and flexibly.

7.4. Modifications

The information context in the FRAME model is often overlooked (See Figure 1). The information context asks researchers to define the scope; all aspects and intersections fit within each, defined context. The authors of the “augmented FRAME” did not so much create a new version of the model but changed the scope appropriately. Rejecting the model for contextual reasons, requires careful thought. For example, suggesting that it cannot be applied to a K-12 context can be contested. Although the FRAME model was originally developed within a higher education context, the original Master’s thesis by Koole [4] includes learning theories that connect various levels of education. Koole, for example, refers to Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development [15], which is most often associated with childhood learning processes. Furthermore, if the context is K-12 or in/formal learning, it can be defined in the information context. The characteristics of all the aspects would be described within the specified context. More thought should also be given to the addition of an extra circle for context [57]; because the context is already a part of the FRAME model, the extra circle seems redundant.

As educators, we strive to ensure that learners occupy a significant place in education. Wong reconfigured the FRAME model so as to place the learner at the center of the mobile learning process. However, this upsets logic of set theory. When circles overlap, there are shared elements. The overlapping of all the circles cannot result in a learner aspect; the center must contain element of all the circles. In addition, in the original FRAME model, the curriculum is part of the social learning intersection (See Figure 1). Currently, as Koole moves toward a more socio-materialist philosophy, the co-creation of the social and the material is jeopardized when the human is positioned as more significant than the other elements [22]. Wong’s work, however, is highly valuable. In future descriptions of the social-learning intersection, curriculum should be explicitly listed. Similarly, Pani and Mishra’s work has led us to consider whether the social-learning intersection could be more aptly named “mobile pedagogy” [57].

Lefrere’s suggestion that ubiquitous or pervasive learning could occupy the center of the FRAME model (see Figure 1) is an astute observation [58]. This suggests that there is some thinking about how the model(s) can be successfully transitioned to different technologies. However, it is unclear if Lefrere is suggesting that mobile learning and ubiquitous or pervasive learning are the same phenomenon. And, this brings us to questions of definitions and nomenclature. There may be a philosophical piece here that requires further deliberation. Does the different nomenclature suggest a shift in semantics surrounding mobile learning or a shift in the ontology of mobile learning?

8. Conclusions and Future Research

This paper has only examined two of many models in the field of mobile learning. The FRAME and the 3-LEF models were selected for this study because they have amassed more than 10 years of references. It is encouraging that the models have been implemented across a wide range of topics, fields of study, and geographic contexts. As researchers and practitioners, our team had hoped to gain some insights into how researchers selected and rejected models/frameworks. The critiques, reasons for use, and modifications have provided us with additional ideas of how we might “tweak” the FRAME and 3-LEF in our own work.

At a more general level, we have begun thinking about how researchers in the mobile learning field are approaching model selection and evaluation. While some authors indicated that they were drawn to the constructivist approach of the FRAME model (Koole’s original approach) and the socio-cultural emphasis of both the FRAME and the 3-LEF, there was little evidence for conscious selection of models/frameworks based on ontological or epistemological concerns. We are left with some perplexing questions: Are mobile learning specialists making logistical decisions in which models/frameworks are chosen for criteria such as ease of use? Are they basing their decisions on a particular philosophical position, or are we seeing the emergence of new models because there is something yet unforeseen, and therefore unaddressed, in the nature of mobile learning? Similar reviews of other models would help us understand how mobile learning researchers and practitioners evaluate and choose their research tools.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.; Data curation, R.B., K.A. and D.L.; Formal analysis, M.K.; Methodology, M.K.; Project administration, M.K.; Writing—original draft, M.K.; Writing—review & editing, M.K., R.B., K.A. and D.L.

Funding

This research was funded by the Office of the Provost Faculty Recruitment and Retention Program, University of Saskatchewan grant number 416033.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to John Traxler who suggested we examine two models/frameworks in tandem.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Nvivo codes and descriptions.

Table A1.

Nvivo codes and descriptions.

| Top Level Node | Sub Node | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Applied | The model/framework was applied. | |

| Area | Field or area of the paper (i.e., museums, biology, architecture, etc.). | |

| Conclusions | Significant conclusion or results from research. | |

| Country of author | Country in which the author lives/works. | |

| Country of research | Country in which the research was conducted. | |

| Critique | Critiques of the FRAME or 3-LEF. | |

| Date | Year of publication. | |

| Extends another model | The seminal paper, model/framework was used to develop or extend a different model. | |

| Literature review | The seminal paper, model/framework was mentioned in the literature (or other parts of the paper). | |

| Methods/methodology | These nodes are used to document the types of papers or studies as described by the authors themselves. Most names are self-explanatory. | |

| Action research | ||

| ANT | Actor Network Theory. | |

| Content analysis | ||

| Conversation analysis | ||

| Delphi study | ||

| Diary | Journal, notes. | |

| Ethnography | ||

| Focus groups | ||

| Grounded theory | ||

| Interaction analysis | ||

| Interviews | ||

| Observation | Qualitative or quantitative uses. | |

| Phenomenography | ||

| Phenomenology | ||

| Survey | Includes questionnaires; qualitative or quantitative. | |

| Task analysis | ||

| Visual methodology | ||

| Experimental | Quantitative. | |

| Quasi-experimental | Quantitative. | |

| Testing knowledge | Quantitative. | |

| Artifact collection | ||

| Case study | ||

| Descriptive study | ||

| Design-based research | ||

| Explanatory study | ||

| Exploratory study | ||

| Systematic review | Document review, extensive literature review. | |

| Evaluation study | ||

| Qualitative | Author indicated qualitative but did not specify. | |

| Quantitative | Author indicated quantitative but did not specify. | |

| Mixed methods | Author indicated mixed methods but did not specify. | |

| Publication type | ||

| Blog | ||

| Book | ||

| Book chapter | ||

| Conference paper | ||

| Conference poster | ||

| Doctoral dissertation/thesis | ||

| Journal article | ||

| Master’s thesis | ||

| Report | ||

| Unknown | ||

| Wiki entry | ||

| Reason for use | The author explicitly states why s/he chose the FRAME or the 3-LEF. | |

| Reference only | The seminal paper is referenced, but not mentioned or cited in the paper. | |

| Springboard to new ideas | The model/framework was used to develop a completely new model/framework. |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Areas of research in which the FRAME and 3-LEF were cited.

Table A2.

Areas of research in which the FRAME and 3-LEF were cited.

| Areas of Research * | 3-LEF 97 References | 3-LEF Applied 10 References | FRAME 201 References | FRAME Applied 81 References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education levels | ||||

| Basic, elementary childhood | 4 | 0 | 7 | 3 |

| High school | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Higher education (college, university) | 4 | 0 | 19 | 7 |

| Informal, non-formal (any age) | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Lifelong learning (adults) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Middle school | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Total | 11 | 2 | 33 | 12 |

| School subjects | ||||

| Architecture | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Art | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Biology | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Business | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Computer science | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Construction training | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Corporate training (incl. banking) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Drama | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Engineering | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Health (nursing, medicine, first aid) | 1 | 0 | 11 | 4 |

| Language learning | 2 | 0 | 20 | 5 |

| Marine education | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Mathematics | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Natural resources | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Nature | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Religion | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Robotics | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sport | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| STEM/STEAM | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Travel and tourism | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 13 | 3 | 51 | 17 |

| Learning activities and skills development | ||||

| Collaborative learning | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Contextual (ambient) learning | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Field trips (including museums) | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Gamification of learning | 3 | 1 | 5 | 2 |

| Intercultural competence | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Literacy, computer, numeracy | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Metacognitive skills | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MOOC | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Social networks | 2 | 0 | 6 | 2 |

| Virtual reality | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wearable technology | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 20 | 2 | 22 | 6 |

| Uptake, design, and support | ||||

| Disabled learner support | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Evaluation | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Faculty uptake, support, and attitudes | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1 |

| Institutional uptake, attitudes, support, policy | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Instructional/learning design | 3 | 0 | 11 | 4 |

| Learner uptake, attitudes, and support | 7 | 2 | 19 | 4 |

| Learning environments–design, evaluation | 7 | 0 | 16 | 9 |

| Pedagogical practices | 6 | 0 | 14 | 4 |

| Teacher (K-12) training, attitudes, and support | 3 | 0 | 10 | 3 |

| Total | 32 | 5 | 86 | 28 |

| M-Learning issues, challenges, potentials | ||||

| Access to education | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Developing world | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| Distance education | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| M-learning issues, challenges, and benefits | 11 | 1 | 20 | 1 |

| Theories, models, frameworks | 3 | 1 | 10 | 1 |

| Total | 16 | 2 | 42 | 4 |

* Note: The overall totals do not add up to the total number of studies because some studies indicated more than one area/topic.

References

- Crompton, H. A Historical overview of m-learning: Toward learner-centred education. In Handbook of Mobile Learning; Berge, Z.L., Muilenburg, L.Y., Eds.; Taylor & Francis Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.; Huberman, A. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Source Book, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, J. (Ed.) Evaluation Cookbook; Heriot-Watt University: Edinburgh, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Koole, M. The Framework for the Rational Analysis of Mobile Education (Frame) Model: An Evaluation of Mobile Devices for Distance Education. Master’s Thesis, Athabasca University, Athabasca, AB, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Koole, M. A model for framing mobile learning. In Mobile Learning: Transforming the Delivery of Education and Training; Ally, M., Ed.; Issues in Distance Education; AU Press: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2009; Volume 1, pp. 25–47. [Google Scholar]

- Vavoula, G.; Sharples, M. Meeting the challenges in evaluating mobile learning: A 3-level evaluation framework. Int. J. Mob. Blended Learn. 2009, 1, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavoula, G.; Sharples, M.; Rudman, P.; Meek, J.; Lonsdale, P. Myartspace: Design and evaluation of support for learning with multimedia phones between classrooms and museums. Comput. Educ. 2009, 53, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanchar, S.C.; Gibbons, A.S.; Gabbitas, B.W.; Matthews, M.T. Critical thinking in the field of educational technology: Approaches, projects, and challenges. In Educational Media and Technology Yearbook; Orey, M., McClendon, V.J., Branch, R.M., Eds.; Springer: Chan, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Danziger, K. The methodological imperative in psychology. Philos. Soc. Sci. Des. Sci. 1985, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ally, M. Mobile Learning: Transforming the Delivery of Education and Training; Anderson, T., Ed.; AU Press: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel, D.P. Educational Psychology: A Cognitive View; Rinehart and Winston, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. The Process of Education: A Searching Discussion of School Education Opening New Paths to Learning and Teaching; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, R.M. The Conditions of Learning; Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Paivio, A. Imagery and Verbal Processing; Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity; Cambridge University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. Usability Engineering; Academic Press: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Preece, J.; Rogers, Y.; Sharp, H. Interaction Design: Beyond Human-Computer Interaction, 2nd ed.; Wiley Publishing, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Shneiderman, B.; Plaisant, C. Designing the User Interface: Strategies for Effective Human-Computer Interaction, 4th ed.; Pearson Education Inc.: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, M.G. Editorial: Three types of interaction. Am. J. Distance Educ. 1989, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, D. Foundations of Distance Education; Routledge: London, UK, 1996; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Koole, M.L. Mobile learning, teacher education, and the sociomaterialist perspective: Analysis of the SMS story project. Int. J. Mob. Blended Learn. 2018, 10, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, J. Adopting a Lifecycle Approach to the Evaluation of Computer and Information Technology. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Y.-C.; Ching, Y.-H. A review of models and frameworks for designing mobile learning experiences and environments. Can. J. Learn. Technol. 2015, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, P.-O.; Jobe, W. Smart Running in Kenya Kenyan Runners’ Improvement in Training, Informal Learning and Economic Opportunities Using Smartphones. In Proceedings of the IST-Africa 2013 Conference & Exhibition, Nairobi, Kenya, 29–31 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hosler, K.A. Pedagogies, Perspectives, and Practices: Mobile Learning through the Experiences of Faculty Developers and Instructional Designers in Centers for Teaching and Learning. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, CO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C.H.H. A Study of Mobile Learning for Guangzhou’s University Students. Ph.D. Thesis, Guangzhou University, Guangzhou, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Levene, J.; Seabury, H. Evaluation of mobile learning: Current research and implications for instructional designers. TechTrends 2015, 59, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandpearl, H. Digital Apps and Learning in a Senior Theatre Class. Master’s Thesis, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Austrlia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, R. Predicting user intentions for mobile learning in a project-based environment. Int. J. Electron. Commer. Stud. 2013, 4, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, M.; Burden, K.; Rai, T. Investigating teachers’ adoption of signature mobile pedagogies. Comput. Educ. 2015, 80, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, M.; Schuck, S.; Burden, K.; Aubusson, P. Viewing mobile learning from a pedagogical perspective. Res. Learn. Technol. 2012, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, T. Places: Evaluating Mobile Learning. Available online: https://placesmobile.wordpress.com/ (accessed on 30 April 2018).

- Haag, J.; Berking, P. Design considerations for mobile learning. In Handbook of Mobile Teaching and Learning; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Y.-C.; Ching, Y.-H.; Snelson, C. Research priorities in mobile learning: An international Delphi study. Can. J. Learn. Technol. 2014, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, P.; Coombs, A.; Pazio, M.; Walker, S. Disruption, Destruction, Construction or Transformation? The Challenges of Implementing a University Wide Strategic Approach to Connecting in an Open World. In Proceedings of the 2014 OCW Consortium Global Conference: Open Education for a Multicultural World, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 23–25 April 2014; pp. 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Timoko, T. Towards an Indigenous Model for Effective Mobile Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning, Istanbul, Turkey, 3–5 November 2014; pp. 315–320. [Google Scholar]

- Du, X. Design and Evaluation of a Learning Assistant System with Optical Head-Mounted Display (OHMD). Master’s Thesis, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Farley, H.; Murphy, A. Developing a framework for evaluating the impact and sustainability of mobile learning initiatives in higher education. In Proceedings of the Open and Distance Learning Association of Australia Distance Education Summit (ODLAA 2013), Sydney, Australia, 4–6 February 2013; pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Westera, W. On the changing nature of learning context: Anticipating the virtual extensions of the world. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2011, 14, 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Al-Aish, A. Toward Mobile Learning Deployment in Higher Education. Ph.D. Thesis, Brunel University, London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, R.; Snow, K. Turn on Your Phones Please: From Distaction to Engagement with Mobile Learning; The Association of Atlantic Universities and Cape Breton University: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2015; Volume 18. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, K.; Parsons, D. A Theory-Ology of Mobile Learning: Operationalizing Learning Theories with Mobile Activities. In Mobile Learning Futures—Sustaining Quality Research and Practice in Mobile Learning (mLearn), Proceedings of the 15th World Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning, Sydney, Australia, 24–26 October 2016; Dyson, L.E., Wan, N., Fergusson, J., Eds.; Unitec Research Bank: Sydney, Australia, 2016; pp. 173–182. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Y.; So, H.-J. Three-level evaluation framework for a systematic review of contextual mobile learning. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning, Helsinki, Finland, 16–18 October 2012; pp. 164–171. [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, J. Assimilate or Accommodate? The Need to Rethink Current Use of the Term ‘Mobile Learning’; The Mobile Learning Voyage-From Small Ripples to Massive Open Waters; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015; pp. 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Khaddage, F.; Christensen, R.; Lai, W.; Knezek, G.; Norris, C.; Soloway, E. A model driven framework to address challenges in a mobile learning environment. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2015, 20, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, R. A Framework for Promoting Teacher Self-Efficacy with Mobile Reusable Learning Objects. Ph.D. Thesis, Athabasca University, Athabasca, AB, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, C.; Alarcon, R.; Nussbaum, M. Implementing collaborative learning activities in the classroom supported by one-to-one mobile computing: A design-based process. J. Syst. Softw. 2011, 84, 1961–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H. A theory of mobile learning. In International Handbook of E-Learning Volume 1 Theoretical Perspectives and Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; Volume 2, p. 309. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman, K.M.; Gannod, G.C. A Critical Analysis of M-Learning Initiatives. In Mobile Learning 2011; Sanchez, I.A., Isaias, P., Eds.; International Association for Development of the Information Society: Avila, Spain, 2011; p. 310. [Google Scholar]

- Alrasheedi, M.; Capretz, L.F. Applying CMM towards an m-learning context. In Information Society (i-Society); Infonomics Society: Essex, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Harpur, P.-A.; de Villiers, R. MUUX-E, a framework of criteria for evaluating the usability, user experience and educational features of m-learning environments. S. Afr. Comput. J. 2015, 56, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAndrew, P.; Taylor, J.; Clow, D. Facing the challenge in evaluating technology use in mobile environments. J. Open Distance E-Learn. 2010, 25, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, H.; Din, R.; Nordin, N. A preliminary study of an authentic ubiquitous learning environment for higher education. In Proceedings of the 10th WSEAS International Conference on E-Activities, Jakarta, Indonesia, 1–3 December 2011; Volume 3, pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Boyinbode, O.; Ng’ambi, D. MOBILect: An interactive mobile lecturing tool for fostering deep learning. Int. J. Mob. Learn. Organ. 2015, 9, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y. A pedagogical framework for mobile learning: Categorizing educational applications of mobile technologies into four types. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2011, 12, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pani, S.; Mishra, J. An effective mobile learning model for learning through mobile apps. IBMRD’s J. Manag. Res. 2015, 4, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefrere, P. Activity-based scenarios for approaches to ubiquitous e-learning. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2009, 13, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpur, P.-A. Evaluation of Usability and User Experience of an M-Learning Environment, Custom-Designed for a Tertiary Educational Context. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fulbright, R. A Quantitative Study Investigating the Effect of Motivational Text Messages in Online Learning. Ph.D. Thesis, Northcentral University, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Talebi, F.; Sasaniyan, M. A study on the FRAME model: Evidence from the banking industry. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2015, 5, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Parsons, D. Evaluating ‘ThinknLearn’: A mobile science inquiry based learning application in practice. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning, Helsinki, Finland, 16–18 October 2012; pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer, V.D.I.; Gemballa, S.; Jarodzka, H.; Scheiter, K.; Gerjets, P. Situated learning in the mobile age: Mobile devices on a field trip to the sea. ALT-J Res. Learn. Technol. 2009, 17, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).