Abstract

The quality of the early childhood workforce is central to service provision in this area, being a major factor in determining children’s development over the course of their lives. Specific skills and competencies are expected from early childhood education and care (ECEC) workforce. Well-trained staff from ECEC settings are an extremely important factor in providing high-quality services which will positively influence the outcomes of children. The present paper analyses the quality of early childhood education and care workforce from the parents’ perspective in the context of Romania’s early childhood reform agenda. A critical review of the specific situation of the early childhood system in relation to the workforce from this sector is made in the first part of the paper in order to highlight the complexity of this issue. In the second part, the authors will present the results of empirical research developed in 2017 using qualitative and quantitative methods in order to assess the activity of early childhood education and care staff. The main challenges in this field as they emerge from research will be analyzed, the findings having implications for policy-makers and practitioners in the field of ECEC services.

1. Introduction

Early childhood development is a very important stage in defining the path of a person’s life [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. In this period of individual life, change happens rapidly in many areas of development (emotional, physical, cognitive, and social). The most popular category of programs for early childhood development and education is represented by early childhood education and care services (ECEC) which cover all forms of early childhood education and early childhood care services under an integrated system (for the children from age zero or one to the compulsory schooling age). According to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) early childhood educational development (ISCED level 1) has educational content designed for younger children (up to two years of age), while pre-primary education (ISCED level 2) covers children from three years of age to the start of primary education (ISCED level 1). Admission to compulsory primary education depends mainly on the age of the child, and starts at the age of five or six in most of the EU Member States [5].

From a socio-economic perspective, the development of the policies in the field of ECEC services was correlated with high female employment rates, a key driver of governments’ interest in expanding ECEC services. Many European governments put family and childcare policies into place to help couples to have children and to ensure a good balance between work and family responsibilities [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16].

For all Member States of the European Union the availability of qualitative and affordable early childhood education and care services for young children is an important issue on internal agendas. In order to achieve the Europe 2020 Strategy target regarding early childhood education and care services (participation of at least 95% of children between the age of four and compulsory school age by 2020) national systems of ECEC services must improve their quality and effectiveness. Previous studies [5,10,11,13] have shown that five areas need to be addressed in order to improve the quality of ECEC provision: the access to ECEC, the workforce, the curriculum, the evaluation/monitoring process, and the governance/funding of ECEC services.

In a communication entitled “Early childhood education and care: providing all our children with the best start for the world of tomorrow” (COM (2011) 66 final) [9] adopted by the European Commission in February 2011, the importance of ECEC services in child development is underlined, especially in the case of disadvantaged children, with the potential to help lift children out of poverty and family dysfunction.

Despite numerous debates on the ECEC services subject in all Member States, harmonized statistics on this issue are often missing due to the fact that many countries have different care facilities with different quality measures and requirements. Furthermore, the cross-national research and resource databases focused on ECEC workforce are limited [17].

2. Development of ECEC System in Romania: Key Issues

According to the national legal framework in the field of education (Law no. 1/2011) early education (0–6 years) covers the ante pre-school education level (3months to 3years) and pre-school education level (3–6 years) (see Table 1). Nurseries (crèches) offer both social and educational services, while kindergartens are part of the pre-university education system.

Table 1.

The structure of ECEC system in Romania.

The types of services offered by early childhood education units are: (1) early education services based on a national curriculum centred on the physical, cognitive, emotional, and social development of children, and on the early remediation of potential difficulties/deficiencies in development; (2) child care, protection and nutrition; (3) child health surveillance services; and (4) complementary services for child, family, respectively counselling, parenting, and information services.

The quality of early childhood workforce represents a core issue to service provision in this area, being a core factor in determining children’s development. Specific skills and competencies are expected from the ECEC workforce. Many studies in the field indicate that staff qualifications are the key factor in providing high-quality ECEC services [3,4,5]. A large body of research has shown that working conditions and professional development are essential components of ECEC quality [4,10,12,18,19], these quality components being linked to children’s cognitive and non-cognitive outcomes. In many cases, good working conditions can reduce the constant staff turnover in the ECEC system, the retention of childcare staff being a core indicator for ECEC quality programs. Working conditions may influence the satisfaction of childcare staff within their workplace, which is likely to affect the ability and willingness of professionals to provide stable relationships and attentive interactions with children [1]. Research evidence shows that the ongoing professionalization of staff is a key element in guaranteeing children’s positive outcomes [20]. An important issue linked to the quality of care that children receive is the staff–child ratio, in many cases used as a proxy to measure the quality in ECEC services [10,11]. A large body of research has found that the child–staff ratio is linked to children’s cognitive performance and linguistic assessment [12,19,21,22]: the lower the ratio is, the better it is for the children.

In 2015, according to Eurostat statistics, in some European Member States, including Romania, child–teacher ratios were particularly high (France, 21.5; Cyprus, 17.8; Holland, 16.3; Romania, 16.3) a reality that can negatively affect early childhood education (ISCED 0). Lower child–teacher ratios reported in Sweden (6.1) and Germany (7.8) correlate with an effective early childhood education system. The indicator refers to all ECEC services, the child-teacher ratio being different, in many countries, considering the type of institution and in accordance to the differences between regular institutions and institutions that offer extra ECEC programs to combat educational disadvantage. However, national data on these issues are not available to ensure comparability across countries. In ECEC services, the dominance of women is a clear issue. In 2013, available data from Eurostat indicated that the proportion of men ranged from 1.2% of the total (in Austria) to 4.7% (in Spain). The ECEC market does not seem to be attractive in many European countries being characterized by low wages and, in some cases, by different educational requirements that negatively influence the quality of childcare. Along with staff working conditions, professional development is also an essential component of ECEC quality, both initial and continuing training enabling staff to fulfil their professional role [5,17,23,24]. Continuing professional training of the ECEC workforce has a major impact on children’s outcomes. It is important to develop common education and training programs for all staff working in an ECEC context: for example, preschool teachers, assistants, educators, and family day carers. From this perspective, the on-going professionalization of ECEC must be sustained through coherent policies. Empirical studies [17,21,23] demonstrate that stimulating environments and high-quality ECEC activities are fostered by better-qualified staff. In the majority of cases, qualifications are one of the strongest predictors of staff quality. However, research in the field has also shown the importance of the length of the work experience in the case of the ECEC workforce. A required qualification level for ECEC staff varies between European Member States. A Bachelor’s degree represents, usually, the minimum level for staff working with children three years of age and over. There are also countries where a Master’s degree is the minimum qualification (France, Italy, Portugal, and Iceland). As a general rule, the younger the children are, the lower the minimum qualification requirements for staff are [5,11,12,13]. Not all European Member States have developed regulated home-based ECEC services, Romania being one of these cases. In countries that provide regulated home-based ECEC services, a minimum formal qualification or specific training is indicated and may be a requirement for accreditation. In general, countries with regulated home-based ECEC provision have mandatory training courses for staff working in home-based settings, but a formal qualification is not required [17,25,26]. A diagnosis of the ECEC system realized in 2014 at the request of the European Commission [13] showed that one of the significant challenges for almost all countries is to bring the profession of childcare workers more in line with that of other teachers. The existence of poorly-qualified staff in ECEC services is a general concern of the European Member States. Starting from this reality, many Member States are in the process of restructuring their national qualification systems for workers in the early childhood field in order to raise the qualification levels, and steps in this respect are also being achieved in Romania. The Seepro project on systems of early education/care and professionalization in Europe, funded by the German Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth, shows that, in 2007, a certain progress was noticed in terms of the evolution of the teaching career in Romania. Special measures have been taken to restructure the methodology for continuous teacher training and to modify the teaching career evolution system [27]. However, the ECEC system also experiences difficulties in retaining qualified graduates. A large body of research has demonstrated that this may be due to the traditionally low wages and status of people who work in this sector [28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

In 2002, the European Council set targets for the provision of childcare services in European Member States known as the Barcelona targets: (1) at least 90% of children between three years old and the mandatory school age, and (2) at least 33% of children under three years of age, should have had access to formal childcare provision by the end of the year 2010. However, the Barcelona targets set in 2002 made no reference to the ECEC workforce, even if the quality of ECEC services, which is an important indicator for assessing ECEC services, depends in a great measure on the quality of the ECEC workforce. The situation registered in 2010 demonstrated that the approach designed to reach the Barcelona targets must be changed, all the factors having an influence in raising the enrolled ratio of children up to six years being subject to reconsideration, including the workforce. According to Eurostat, in 2010, for the category of children between three years of age and the compulsory school age, only 11 Member States achieved the objective of 90% enrolment rate. The situation for children under the age of three was even worse, with only 10 Member States reaching the Barcelona target. In both cases, Romania was not among the countries that achieved the indicators. National statistical data from all European Member States show that the use of childcare facilities increases with children’s age. Despite the fall in population in 2017, a shortage of ECEC places for children under three years old is likely to persist in Romania, but many European countries are experiencing this problem. Even if for the age group zero to three years, Romania is still in a long process of reconstruction of policies (although there is a growing demand for these types of services), this situation being reflected in the evolution of specific rates of enrolment of children in nurseries that record percentage increases from one year to the next [35]. An insufficient number of nurseries is slowing down the process of many parents returning to the labour market.

The reform of early childhood education and care in Romania started in 2006. In 2008, an early childhood education reform project was implemented and included integrated program targets for all staff working in kindergartens. The integrated professional development program aims to promote a new educational culture in ECEC, enabling all staff working with children to use coherent educational practices based on the same understanding of the importance of the early years for supporting children’s learning and development.

The education requirements for ECEC staff are regulated by legal provision. Qualification in the preschool education range from graduates of pedagogical high schools (with specializations in early childhood education) to staff with university degrees in pedagogical studies and specializations in primary or preschool education.

The structure of the nurseries (crèches) staff consists of: managers, teaching staff (educator, child carers), specialized staff (medical assistant) and non-teaching staff (administrator, carer, cook, accountant). The non-teaching staff of the nurseries must complete a specific, continuous training module on early education lasting for at least 30 h. The training module should cover at least the following topics: (1) the principles of early education; (2) the global approach of the child and team work; and (3) activities to develop parenting skills. Referring to kindergartens, the structure off staff consists of: (1) teaching staff, and (2) non-teaching staff.

3. Quality of ECEC Services and Workforce in Romania: Empirical Evidence

3.1. Methods and Study Design

In order to identify the factors that influence the use of early education services (kindergartens/nurseries) in Romania, the authors developed a methodology in two phases: (1) a qualitative methodology (focus groups and semi-structured interviews) to identify perceptions related to kindergarten and nursery staff, and (2) a quantitative methodology (survey-based questionnaire) to assess at a national level the overall activities of ECEC staff based on opinions expressed by parents of children enrolled in ECEC services. One specific module from the questionnaire was designed specifically to assess the staff’s activities involved in ECEC settings (kindergartens and nurseries).

The following themes were subject of the assessment:

- Staff Numbers in Childhood Education and Care Settings;

- Quality of the Professional Qualification of Staff in Childcare Settings;

- Quality of the Educational Process in Childcare Settings; and

- Quality of the Healthcare and Caring Activities.

The entire methodology is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

The methodology framework.

The field activity was carried out during September and October 2017. All of the ethical considerations (information, participant consent, safeguarding and disclosure issues) were ensured during the study, in both phases of the research. Procedures for selecting focus groups and interviews respondents were in accordance to the methodological approach for implementing qualitative research methods. Qualitative data from the focus groups and semi-structured interviews were transcribed, and thematic analysis was used to identify the core issues of ECEC staff activities which were introduced in the questionnaire applied at the national level, in order to assess parents’ opinions regarding workforce in the ECEC settings (kindergartens/nurseries). After data collection, quantitative descriptive analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.

3.2. Results

In the first phase of the research, during interviews with ECEC services managers and parents of children enrolled in the ECEC system, several important insights emerged (see Table 3). Most participants in the focus groups believe that kindergarten/nursery is the place where staff has a major influence on children’s development. The kindergarten/nursery teacher must be a person very close to the children, more likely ‘a second mother’ than an instructor.

Table 3.

Insights from qualitative research.

The ECEC system should supplement the education received by the children within the family. Therefore, the quality of the workforce in this sector is essential. European trends are increasing the professionalization of staff working in ECEC services [13].

Particularly in Romania, the overall staff profile remains very diverse and work in this sector is poorly remunerated. As a general rule, educational work is allocated to qualified staff and care work to less qualified staff, even if, for children up to three years old, both activities are equally important.

Interviews with kindergarten/nursery managers also raised a number of issues with direct reference to the ECEC workforce: (1) the need to hire qualified staff for counselling services, and (2) regular training activities for kindergarten and nursery teachers. The diversity of the children in their charge and the range of issues tackled by ECEC staff require continuous reflection on pedagogical practice, as well as a systemic approach to professionalization. In Romania, training for working with children at risk must be done more frequently in order to increase the gross enrolment ratio in pre-primary education. Early childhood education and care reform in Romania, which started in 2006, is still in the process of development.

In the second phase, with the survey-based questionnaire, many issues that emerged from the qualitative research were tested at national level in order to shape the general situation. The research explored both the variables related to the number of the staff and those that measured the quality, considering that, in childcare settings, not only the aspects related to the number of staff, training, and skills of the workforce involved in teaching and caring activities, but also those related to the quality of the educational process, are essential.

3.2.1. Perception of Staff Numbers in Childhood Education and Care Settings

Most often, with regard to the staff involved in ECEC services, data collected are reported in terms of staff ratio, considering only the workers implicated in teaching and education activities. As different types of professionals work in early childhood education and care services, we appreciated as being equally important to collect perceptions about the number of educators, medical, and auxiliary staff. The parents expressed positive opinions regarding the number of educators in childhood settings (kindergartens and nurseries), with more than two-thirds of the respondents considering their number as being sufficient for the teaching activities. Shortages of staff are perceived especially in the case of non-teaching personnel, such as nurses and auxiliary staff (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Perceptions regarding staff numbers (%).

Previous research proved that in childhood education and care settings, a lower child ratio ensure the necessary conditions to provide better child outcomes, higher quality interactions between teachers and children, and better educational and care processes [36,37,38,39,40]. Our research proves that the responses of the parents in respect to the adequacy of the staff number are consistent with results from previous studies.

Although rural population comprises almost a half of the Romanian population (46.2%, National Institute of Statistics, 2016) it has been often neglected in research. The present study allows to generalize the results to all rural communities, as it is based on a representative sample. The residential area of the parents, participants to the survey, pointed to discrepancies between different types of workforces involved in early childhood education and care services. Even the early childhood education is recognized as being essential for the remainder development of a child, the Romanian legal framework does not set compulsory obligations for the parents to enrol their children in preschool care and educational services. As a consequence, the development of such facilities in rural areas is characterized by low public investments, rural localities having, at the same time, a reduced capacity to attract private initiatives in ECEC services, due to the limited possibilities of parents to buy such services. In the case of parents from rural areas, the views concerning the number of educators in the childhood setting is much more positive compared with the opinions of parents from urban areas: almost 17 percentage points (pp) more parents from rural areas expressed a higher level of appreciation regarding the number of educators in kindergartens and nurseries. Similar results characterized the opinions related to the auxiliary staff (personnel involved in caring activities): 16.9 pp more parents from rural areas had a positive valuation. In the case of medical personnel, the differences based on area of residence were less significant, with only a 3 pp difference between parents from rural areas and those from urban areas, with respect to the existence of an adequate number of nurses in early childhood education settings (see Table 5). Arguments that may explain these findings are to be found in the availability of and access to childcare and educational services in urban and rural areas, the ECEC services in rural areas being characterized by scarcity in isolated rural settings and long distances between home and educational facilities. The total number of kindergartens was about 12.4 times more present in urban areas compared with the situation in rural areas, after a decrease of about one third between 2011 and 2014, and approximately 7% of these facilities were difficult to access, especially in rural areas [41]. Between 2014 and 2015, 81.8% of rural children aged 3–5/6 years were enrolled in pre-school education compared to 97.7% in urban areas [42]. Living in smaller communities, rural parents tend to develop their own values, customs, traditions, and opinions with regard to education [43] based on their socioeconomic status, educational level, access to less educational resources, more difficult child care arrangements, fewer jobs, and lower financial resources [37,44,45]. Being less educated and having lower expectations, the respondents from rural localities tend to have better opinions and to express a much greater level of satisfaction regarding all types of staff involved in child care and education services.

Table 5.

Perceptions regarding staff numbers, based on the residence area (%).

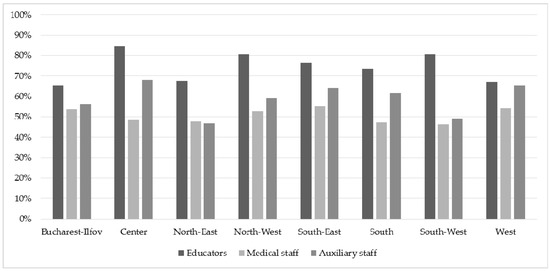

A further analysis of the parents‘ views regarding the adequacy of the workforce in childcare settings revealed significant differences between administrative regions per type of personnel: Higher levels of positive appreciations concerning the number of educators characterized parents from the Centre region, the North-West, and the South-West regions, while the lowest levels of positive feedback characterized the responses of parents from the North-East and West regions. The medical staff (nurses) and the auxiliary staff recorded lower levels of positive opinions, compared with those mentioned for education. Parents from the South-East and West regions, and those from the Centre and the West regions, had the highest levels of satisfaction regarding the number of medical and auxiliary staff, respectively (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Positive perceptions regarding staff numbers, based on regions (%).

In the absence of any official data concerning the regional distribution of ECEC services, and considering the fact that the responsibility with regard to organization, operation, maintenance and financing of such services belong to local authorities, we may only assume that the perceptions of parents are influenced by the low interest of public authorities in the early education and care of the children. Thirty-five percent and 34.8% of the parents from urban areas in the North-East region and the -South region, respectively, consider that the number of educators is insufficient. Almost a quarter (24.3%) of the parents from the rural areas in the North-East region share the same opinion regarding the educators and over half (50.8%) of the parents from urban areas in the South-East region appreciate that the number of medical staff in childcare settings is insufficient. The results are also consistent with the distribution of parents‘ perceptions based on residence area, as—North-East and South regions are among the regions with the highest percentage of people at risk-of-poverty 36.1%, respectively 24% (according to Eurostat data for 2016).

3.2.2. Parents’ Ratings Regarding the Quality of the Professional Qualification of Staff in Childcare Settings

The results presented in this section fit well with previous research [33,46], which have already underlined that the quality of the training of educators is an important determinant of the quality of educational process in childcare settings. The perspective of parents offers significant input to appraise the quality of staff qualifications. The overall assessment of the quality of training in the case of the teaching staff was very good, compared with the ratings of the non-teaching staff (medical and auxiliary staff). The answers revealed a low interaction between parents and non-teaching staff, as more than 10% of the parents were not able to assess the quality of the professional skills due to a lack of communication with the staff involved in the caring activities or medical assessment (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Distribution of answers in the quality of training of the workforce (%).

The residence area underlined larger discrepancies between parents from urban areas and those from rural areas, in terms of poor interaction and communication with medical staff and other auxiliary staff: 19.2 pp and 9.3 pp more parents from rural areas could not appreciate the quality of skills of medical and auxiliary staff, respectively. Perceptions of parents in rural areas may be influenced by the social, economic, and educational characteristics and additional research should examine the factors that mostly influence the communication and interaction process with non-teaching staff.

Communication between medical staff and parents from rural areas in theSouth-West, the South and the Centre administrative regions was very poor, as 56.8%, 50.1%, and 44.6% of parents, respectively, were not able to assess the quality of training of this type of personnel. Over a third of parents from rural settings in the South-West (40.5%) and the Centre (31%) regions declared that they were not able to appraise the quality of the staff involved in caring activities due to a lack of interaction, compared with only 10.3% and 3.3% in the case of the parents from urban areas from the same regions, respectively.

3.2.3. Parents’ Ratings Regarding the Quality of the Educational Process in Childcare Settings

One of the important questions for the research was the level of parental appreciation with aspects related to the educational process. Five statements related to the following aspects of the quality of the educational process were included in the questionnaire:

- Quality of the teaching;

- Well-being and support for the child; and

- Support for parents and educator–parent collaboration.

Most often, parents’ perceptions have been related to their social and economic background [47] or to demographic characteristics (age, cultural norms, etc.) [48]. Consistent with previous studies, the majority of parents rated positively, and over a half indicated ‘always’ to the assessment of the statements related to the educational process; 74.8% of the parents considered that the educators answer promptly whenever they need guidance, and 76.2% of them appreciated that the educator is providing the feeling of trust and safety in relation with their child. Less appreciated compared with the previous two statements was the ability of the educators to listen and to consider in the teaching process the suggestions of the parents (64.7%). Results point that parents tend to associate the quality of the educational process mostly with the child interactions with staff, the staff and parents communication, and the safety feeling dimensions.

The positive evaluation stressed the importance of communication and peer relationship with the educators, from the parents’ perspective. The area of residence suggested that the parents from urban areas express lower levels of appreciation compared with those from rural areas, results in line with the opinions about the number of teaching staff. In terms of support and guidance, parents from urban areas considered there to be room for improvement (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Positive perceptions (‘always’ category) regarding the quality of the educational process, based on area of residence (%).

While the child–adult ratio is one dimension for the overall quality of the ECEC services, other studies have shown that this indicator is correlated with measures applied to assess quality, including higher-quality interactions between the child and the caregiver [45]. The results described in this section reveal that parents from Bucharest–Ilfov region recorded the lowest positive valuing for the statements: ‘Offers support and guidance in education of the child’ (45.1%), and ‘Listen and consider the suggestions concerning the education of my child’ (48.4%). These ratings are outside the pattern found in case of other regions. Among the Romanian administrative regions, Bucharest-Ilfov is by far the most reached and characterized by numerous and diverse ECEC services (both private and public). Considering also the socioeconomic characteristics of the population’s region and the prevalence of the persons with high educational level, it is expected that parents from this region to have the highest expectations in terms of the necessary quality level of educational process. Results could also point to a more active engagement of parents in their children’s education.

3.2.4. Parents’ Ratings Regarding the Quality of the Healthcare and Caring Activities

Previous sections explored the variables related to the quality of the child-staff relationship considering different types of professionals in ECEC services and the influencethat staff could have on the overall health status and emotional development of the child. Monitoring staff quality is usually conducted through inspections and self-evaluations, and sometimes through parental surveys or peer reviews and staff testing [33]. Our research collected perceptions of parents about the non-teaching staff. Usually, workers involved in caring activities may be involved in preparing and serving the meal, assisting children in different educational activities, etc., relate and contribute to the progress and development of the child, as well as to the creation of a sense of warmth and inclusion. The results of the current research underline a less positive feedback of parents related to healthcare activities. Almost half of the parents considered that the medical staff within the childhood education and care settings offer the guidance and support in matters related to child health, or respect the policy regarding the access of sick children within the premises (see Table 8). One explanation that may help the understanding of the findings is that as families face many challenges, parents have higher expectations from all professionals involved in ECEC services and require that non-teaching staff to expand responsibilities and to include the support offered in child health matters, among their day-to-day tasks.

Table 8.

Parents’ attitudes towards the quality of the healthcare activities.

Parents from the Centre and the South-West regions expressed the lowest positive feedback with regard to the statement ‘Respects the organizational policy regarding the access of sick children within the premises’: 40.2% and 41.8%, respectively, of the parents from these regions. The least supported in matters related to child health are the parents from the Centre (33%), the Noth-East (42.3%), and the South (42.7%) administrative regions.

In general, parents from urban areas assessed differently the medical activities, compared with parents from rural areas. With regard to the ability of the medical staff to provide safety, confidence, and to develop a good emotional relationship with the children, parents from rural and urban areas share a similar assessment: 50.8% of the parents from urban areas and 51.6% of the parents from rural areas consider that the medical staff offers security, confidence, and has a good relationship with the child.

Quality of care, such as quality of the carer–child relationship, is highly valued by parents, with more than two-thirds of them providing a positive assessment (see Table 9), and parents from urban areas (64.9%) to a greater extent, compared with parents from rural areas (75.4%), as following the educators, the carer is the ECEC’s type of worker that relates mostly with the child during their daily activities.

Table 9.

Parents’ attitudes towards the quality of the caring activities.

There were no significant differences between parents from rural and urban areas in terms of appreciation with regard to the cleaning and safety of the childcare settings: 76.9% (rural) and 75.1% (urban) considered that the kindergartens/nurseries are ‘always’ clean and safe. This is an expression of the importance of non-teaching activities and the reflection into practice of the legal standards set for ECEC services delivery.

Although few parents negatively evaluated the quality of caring activities, there were lower levels of satisfaction with regard to a specific aspect: the willingness of the caring staff to help children whenever necessary (see Table 9).

4. Conclusions

This article brings into light the parents’ perceptions about the quality of workforce involved in early childhood education and care services, in the Romanian context. The study has significant contributions in terms of examining rural and urban difference and analysis of different types of professionals involved in the provision of ECEC services in Romania. As the demand for early childhood education services is growing, the article provides valuable information about the level of parents’ satisfaction with the quality of the ECEC workforce, demonstrating that parents are aware of particular aspects of educational and caring activities and concerned for their children’s wellbeing and development.

Although the rural population comprises almost a half of the Romanian population, it has been often neglected in research studies. The article allows to generalize the findings to all rural communities, as the research was based on a representative sample. The number of the workforce is assessed positively for all teaching and non-teaching types of personnel involved in ECEC services. However, the area of residence indicates differences in responses between parents from rural and urban localities. The development of such facilities in rural areas is characterized by low public financing and a reduced capacity to attract private investments in ECEC services.

The results of the current research underline positive appraisals regarding the quality of educators, but are less positive for the medical and caring staff. There were no significant differences between parents from rural and urban areas in terms of appreciation with regard to the cleaning and safety of the childcare settings and this is an expression of the importance given to non-teaching activities. Differences related to the area of residence have also emerged regarding the quality of the educational process in direct relation with the appreciation regarding the number of teaching staff.

In Romania, the overall staff profile remains very diverse and work in this sector is poorly remunerated. The work in this field is influenced by the staff–child ratio, which is particularly high in Romania. Government policies must take into account several changes that will directly influence the structural quality of the ECEC system: (1) raise the educational requirements of ECEC staff, and (2) change the regulation of child–staff ratios.

In recent years, policy has become increasingly concerned with the quality of childcare services. This is also due to the fact that the tasks of the ECEC staff are influenced by new pedagogical approaches, but also a series of societal challenges which influences work in this sector. The childcare profession in Romania has taken a distinct path of development which is linked to the history of ECEC in general. Romanian parents still have a maternal tradition in the care of young children, but the assignment of childcare as part of social welfare has had an important role in establishing the development path of the ECEC services.

Acknowledgments

This paper was accomplished through Nucleu Programme, implemented with the support from the Ministry of Research and Innovation, contract no. 17N/2016, PN 16440305. Beneficiary: National Scientific Research Institute for Labour and Social Protection-INCSMPS, Bucharest, Romania.

Author Contributions

Aniela Matei has been responsible for the project coordination and is the main writer of Section 1 and Section 2, and of qualitative analysis from the Section 3.2. Mihaela Ghenţa is the main writer of Section 3.2.1, Section 3.2.2, Section 3.2.3 and Section 3.2.4. All authors have planned the article and contributed to the discussion and conclusions in collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- OECD. Doing Better for Families; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011; pp. 17–53. ISBN 978-92-64-09872-5. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. PISA 2009 Results: Equity in Learning Opportunities and Outcomes (Volume II); OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009; ISBN 978-92-64-09146-7. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Starting Strong II: Early Childhood Education and Care; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2006; ISBN 9264035451. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Starting Strong III—A Quality Toolbox for Early Childhood Education and Care; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012; ISBN 9789264123564. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Working Group. Early Childhood Education and Care. Proposal for Key Principles of a Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education and Care; Report of the Working Group on Early Childhood Education and Care under the Auspices of the European Commission; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, J.L.; Sanders, M.G.; Simon, B.S.; Salinas, K.C.; Jansorn, N.R.; Van Voorhis, F.L. School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action, 3rd ed.; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 7–57. ISBN 978-1412959025. [Google Scholar]

- European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Early Childhood Care: Working Conditions, Training and Quality of Services—A Systematic Review; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen, G. Incomplete Revolution: Adapting Welfare States to Women’s New Roles; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 75–145. ISBN 978-0745643168. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Early Childhood Education and Care: Providing All Our Children with the Best Start for the World of Tomorrow; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission’s Expert Group on Gender and Employment Issues. The Provision of Childcare Services—A Comparative Review of 30 European Countries; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Barcelona Objectives: The Development of Childcare Facilities for Young Children in Europe with a View to Sustainable and Inclusive Growth; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.R. Caring for Paid Caregivers: Linking Quality Childcare with Improved Working Conditions. Univ. Cincinnati Law Rev. 2004, 73, 399–431. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Use of Childcare in the EU Member States and Progress towards the Barcelona Targets. Short Statistical Report No. 1; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. The Child Care Transition: A League Table of Early Childhood Education and Care in Economically Advanced Countries. Innocenti Report Card 8. 2008. Available online: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/rc8_eng.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2017).

- Eurofound. Opting out of the European Working Time Directive. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef1527en.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2017).

- Eurofound. Working Time Developments in the 21st Century: Work Duration and Its Regulation in the EU. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef1573en.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- Oberhuemer, P.; Schreyer, I.; Neuman, M.J. Professionals in Early Childhood Education and Care Systems: European Profiles and Perspectives; Barbara Budrich: Opladen, Germany, 2010; pp. 366–381. ISBN 9783866492493. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Tackling Social and Cultural Inequalities through Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe; Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Education International (EI). Early Childhood Education: A Global Scenario; Education International ECE Task Force: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, M.; Vandenbroeck, M.; Peeters, J.; Lazzari, A.; Van Laere, K. CoRe: Competence Requirements in Early Childhood Education and Care. European Commission: DG Education and Culture. 2011. Available online: https://download.ei-ie.org/Docs/WebDepot/CoReResearchDocuments2011.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- Munton, T.; Mooney, A.; Moss, P.; Petrie, P.; Clark, A.; Woolner, J. International Review of Research on Ratios, Group Size and Staff Qualifications and Training in Early Years and Childcare Settings; Thomas Coram Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 1841856517. [Google Scholar]

- International Labor Office (ILO). Policy Guidelines on the Promotion of Decent Working Conditions for Early Childhood Education Personnel. Geneva. Available online: www.ilo.org/sector/Resources/codes-of-practice-and-guidelines/WCMS_236528/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 10 September 2017).

- Fukkink, R.G.; Lont, A. Does training matter? Meta-analysis and review of caregiver training studies. Early Child. Res. Q. 2007, 22, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, A. Early Childhood Education: Pathways to quality and equity for all children. Aust. Educ. Rev. 2006, 50, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Oberhuemer, P. The Early Childhood Education Workforce in Europe. Between Divergencies and Emergencies. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy 2011, 5, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberhuemer, P. Conceptualising the early childhood pedagogue: Policy approaches and issues of professionalism. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2005, 13, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iucu, R.; Manolescu, M.; Ciolan, L.; Bucur, C. System of Early Education/Care and Professionalisation in Romania, 2008. Report Commissioned by the State Institute of Early Childhood Research (IFP) Munich, Germany. Available online: http://www.ifp.bayern.de/imperia/md/content/stmas/ifp/commissioned_report_romania.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2017).

- Barnett, W.S. Low Wages = Low Quality: Solving the Real Preschool Teacher Crisis. Preschool Policy Matters (3). Available online: http://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/3.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- Department of Education and Science. Developing the Workforce in the Early Childhood Care and Education Sector. Background Discussion Paper. 2009. Available online: https://www.education.ie/en/Schools-Colleges/Information/Early-Years/eye_background_discussion_paper.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2017).

- Moss, P. Structures, understandings and discourses: Possibilities for re-envisioning the early childhood worker. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2006, 7, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, D. The costs of being a child care teacher: Revisiting the problem of low wages. Educ. Policy 2006, 20, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, G.H.; Hyatt, D.E. Child care workers’ wages: New evidence on returns to education, experience, job tenure and auspice. J. Popul. Econ. 2002, 15, 575–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janta, B.; van Belle, J.; Stewart, K. Quality and Impact of Centre-Based Early Childhood Education and Care. European Union, 2016. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1670.html (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- Lloyd, E.; Penn, H. (Eds.) Childcare Markets: Can They Deliver an Equitable Service? The Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2012; p. 264. ISBN 978184742933. [Google Scholar]

- Matei, A. Developing ECEC in Romania: Between Perceptions and Social Realities. Roman. J. Multidimens. Educ. 2014, 6, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Huntsman, L. Determinants of Quality in Childcare: A Review of the Research Evidence: Literature Review; Centre for Parenting and Research: Sydney, Australia, 2008. Available online: http://www.community.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/321617/research_qualitychildcare.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2017).

- Maher, E.J.; Frestedt, B.; Grace, C. Differences in Child Care Quality in Rural and Non-Rural Areas. J. Res. Rural Educ. 2008, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dalli, C.; White, E.J.; Rockel, J.; Duhn, I.; Buchanan, E.; Davidson, S.; Ganly, S.; Kus, L.; Wang, B. Quality Early Childhood Education for Under-Two-Year-Olds: What Should It Look Like? A Literature Review. 2011. Available online: http://thehub.superu.govt.nz/sites/default/files/41442_QualityECE_Web-22032011_0.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2017).

- Phillips, D.A.; Lowenstein, A.E. Early care, education, and child development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2011, 62, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlman, M.; Fletcher, B.; Falenchuk, O.; Brunsek, A.; McMullen, E.; Shah, P.S. Child-Staff Ratios in Early Childhood Education and Care Settings and Child Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop, L.M. Investing in children: Breaking the cycle of disadvantage; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Education and Training Monitor 2016 Romania; Publication Office of the European Commission: Luxembourg, 2016; ISBN 978-92-79-51677-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hade, D.J. Parenting and Child Care in Rural Environments. Retrospective Theses and Dissertations, 1165; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, G.; Flor, D. Maternal resources, parenting practices, and child competence in rural, single-parent, African American families. Child Dev. 1998, 69, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, X.; Liu, P.; Ma, Q.; Luo, X. The way to early childhood education equity—Policies to tackle the urban-rural disparities in China. Int. J. Child Care Educ. Policy 2015, 9, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Quality Matters in Early Childhood Education and Care: Slovak Republic; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012; ISBN 978-92-64-17565-5. [Google Scholar]

- Emlen, A.C.; Koren, P.E.; Schultze, K.H. From a Parent’s Point of View: Measuring the Quality of Child Care: A Final Report. 1999. Available online: http://health.oregonstate.edu/sites/health.oregonstate.edu/files/sbhs/pdf/1999-From-a-Parents-Point-of-View.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2017).

- Kovacs, B. Managing access to full-time public daycare and preschool services in Romania: Planfulness, cream-skimming and interventions. J. Eurasian Stud. 2015, 6, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).