“We’re One Team”: Examining Community School Implementation Strategies in Oakland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework and Relevant Literature

2.1. The Community School Model

2.2. Community Schools Research

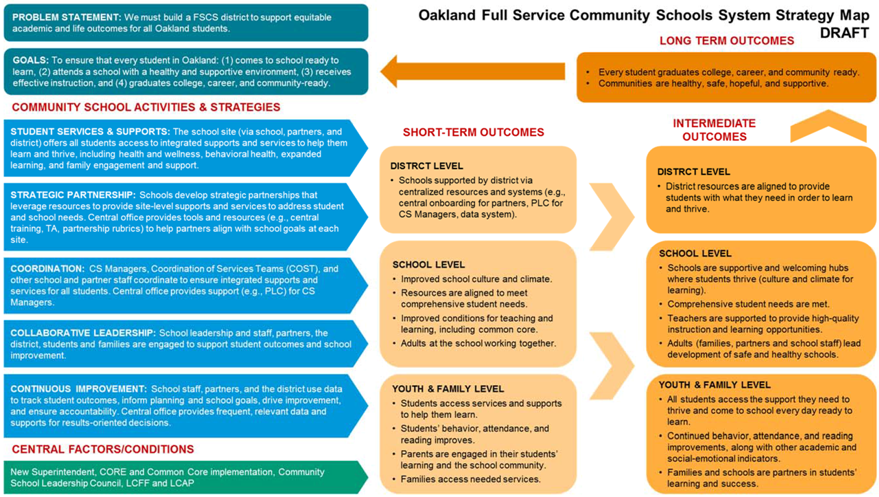

3. Community Schools in Oakland

4. Research Design

4.1. Research-Practice Partnership

- How is the community school model being implemented across OUSD school sites?

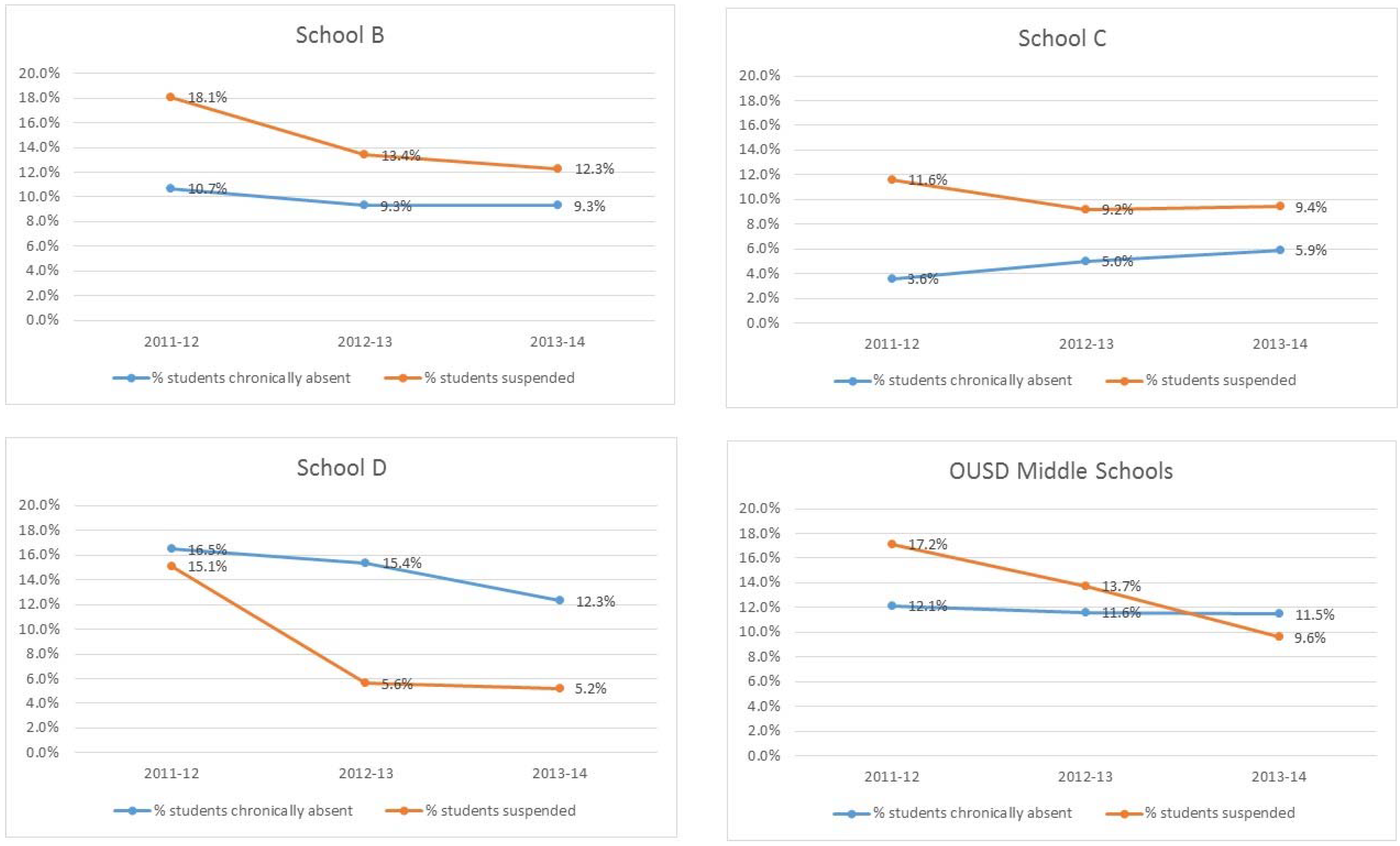

- What patterns in student and school outcomes are emerging across early-adopting schools?

4.2. Sample

4.3. Data Collection and Analysis

5. Findings

5.1. Four Community School Capacities

5.1.1. Comprehensiveness

5.1.2. Collaboration

(Our partners) are behind every single initiative that we do that I would say falls under community schools.… It’s not there’s (partner organization) and (name of school), it’s (partner organization) at (school). We’re just one team. So, I never think of [so and so], any of that team as an outside agency coming in. They’re the core of our school.

5.1.3. Coherence

5.1.4. Commitment

I just said, “Look, here’s what’s happening on our side. Here’s my experience. This isn’t working for us. I think you’re a great program. I think we’re really aligned. Can we do this?” And then, finally, they said, “Yes… Let’s try it.” And so then, we tried it, and I think it was mutually agreed-upon that it worked really well.

So, at this point, I feel like it’s really a true partnership where both of us trust each other and it’s not like I need to hide anything from him or he’s hiding anything from me; it’s to the point where I’ve heard other people tell me how principals aren’t sharing budgets with them. This is the year where… he’s sharing his school’s budget with me. I know exactly how the money is being spent. And same for him, he understands how (my agency) is spending (our) funds.

5.2. Implementation of Key Strategy Areas

5.2.1. Integrated Student Services: Health and Wellness

I think that it’s really great for students to know that they can get services, and it’s very—it’s been incredibly normalizing to students that if you have something going on, that you should go and talk about it. ‘Cause I’ll have students who just in the middle of class, they’ve got their little confidential pass, but they’ll just stand up and be like oh, I gotta go to therapy.

5.2.2. Expanded Learning

When I first came here, people would actually say… in a staff meeting, ‘Why is (this partner) in this meeting? We don’t want them here. We’re a faculty. We’re professionals. And we should be able to have our own meeting and talk about things as teachers, as professionals, without having non-teachers here.’ And that was like four years ago… (The principal) just shut her down immediately…He’s just like, ‘That’s not an option… (this organization) is our partner and they do belong in this meeting.’

5.2.3. Family Engagement

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B. Sample School Profiles

References

- Rothstein, R. Class and Schools: Using Social, Economic, and Educational Reform to Close the Black-White Achievement Gap; Economic Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, K.L.; Entwisle, D.R.; Olson, L.S. Lasting consequences of the summer learning gap. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2007, 72, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, S. The Widening Academic Achievement Gap between the Rich and the Poor: New Evidence and Possible Explanations. In Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances; Duncan, G., Murnane, R., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cuban, L. Reforming Again, Again, and Again. Educ. Res. 1990, 19, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, H.A.; van Veen, D. (Eds.) Developing Community Schools, Community Learning Centers, Extended-Service Schools and Multi-service Schools: International Exemplars for Practice, Policy and Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016.

- Valli, L.; Stefanski, A.; Jacobson, R. Typologizing school-community partnerships: A framework for analysis and action. Urban Educ. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryfoos, J. Full-service schools: A Revolution in Health and Social Services for Children, Youth and Families; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lubell, E. Building Community Schools: A Guide for Action; Children’s Aid Society: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, M. Leadership, Partnerships, and Organizational Development: Exploring Components of Effectiveness in Three Full-Service Community Schools, School Effectiveness and School Improvement. Int. J. Res. Policy Pract. 2015, 27, 157–177. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk, A.S.; Sebring, P.B.; Allensworth, E.; Luppescu, S.; Easton, J.Q. Organizing Schools for Improvement: Lessons from Chicago; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010; pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Blank, M.J.; Melaville, A.; Shah, B.P. Making the Difference: Research and Practice in Community Schools; Coalition for Community Schools: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson-Moore, K.; Emig, C. Integrated Student Supports: A Summary of the Evidence Base for Policymakers; Child Trends White Paper, 2014–05; Child Trends: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Biag, M.; Castrechini, S. The Links between Program Participation and Students’ Outcomes: The Redwood City Community Schools Project; John, W., Ed.; Gardner Center for Youth and their Communities: Stanford, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J.W. The full-service community school movement: Lessons from the James Adams Community School; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Claiborne, N.; Lawson, H. An intervention framework for collaboration. Fam. Soc. J. Contemp. Soc. Serv. 2005, 86, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, L. A First Look at Community Schools in Baltimore; Baltimore Education Research Consortium: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, H.A.; Briar-Lawson, K. Connecting the Dots: Progress toward the Integration of School Reform, School-Linked Services; Parent Involvement and Community Schools, Institute for Educational Renewal: Oxford, OH, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, S.G. Tackling Wicked Problems through Organizational Hybridity: The Example of Community Schools; New York University: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alameda County Public Health Department. Life and Death from Unnatural Causes: Health and social inequity in Alameda County. August 2008. Available online: http://www.acphd.org/media/53628/unnatcs2008.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2015).

- U.S. Census 2000 SF1, SF3, DP1-DP4, CTPP, Census 2010 DP-1. Available online: http://www.bayareacensus.ca.gov/cities/Oakland.htm on (accessed on 27 April 2016).

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2006–2010. Available online: http://www.bayareacensus.ca.gov/cities/Oakland.htm (accessed on 27 April 2016).

- Trujillo, T.M.; Hernández, L.E.; Jarrell, T.; Kissell, R. Community Schools as Urban District Reform Analyzing Oakland’s Policy Landscape through Oral Histories. Urban Educ. 2014, 49, 895–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, K.D.; Penuel, W.R. Relevance to practice as a criterion for rigor. Educ. Res. 2014, 43, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coburn, C.E.; Penuel, W.R.; Geil, K.E. Research-Practice Partnerships: A Strategy for Leveraging Research for Educational Improvement in School Districts; William T. Grant Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, B.; Penuel, W.R.; Allen, A.-R.; Cheng, B.H.; Sabelli, N. Design-Based Implementation Research: An Emerging Model for Transforming the Relationship of Research and Practice in Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education; Teachers College, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 112, pp. 136–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ed-data School Reports, 2013–2014. Available online: https://www.ed-data.k12.ca.us/Pages/Home.aspx (accessed on 4 August 2015).

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. Longitudinal Qualitative Research: Analyzing Change through Time; AltaMira Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wolcott, H.F. Transforming Qualitative Data: Description, Analysis, and Interpretation; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Utilization-Focused Evaluation, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jehl, J.; Blank, M.J.; McCloud, B. Education and Community Building: Connecting Two Worlds; Institute for Educational Leadership: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Dev. Psychol. 1986, 22, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvard Family Research Project. Family Engagement as A Systemic, Sustained, and Integrated Strategy to Promote student Achievement (Project Report); Harvard Graduate School of Education: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jeynes, W.H. A meta-analysis: The effects of parental involvement on minority children’s academic achievement. Educ. Urban Soc. 2003, 35, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapp, K.L.; Kuttner, P.J. Partners in Education: A Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family–School Partnerships; SEDL: Austin, TX, USA, 2013; Available online: http://www.sedl.org/pubs/framework/FE-Cap-Building.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2015).

- Hong, S. A Chord of Three Strands: A New Approach to Parent Engagement in Schools; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, M.; Mapp, K. A Match on Dry Grass: Community Organizing as a Catalyst for School Reform; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Buttery, T.J.; Anderson, P.J. Community, school, and parent dynamics: A synthesis of literature and activities. Teacher Educ. Q. 1999, 26, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M.M.; Hoover, J.H. Overcoming adversity through community schools. Reclaim. Children Youth 2003, 11, 206–211. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, M.G. The role of “Community” in comprehensive school, family, and community partnership programs. Elem. School J. 2001, 102, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, J.O.; Britton, J.H. Schools serving the total family and community. Fam. Coord. 1970, 19, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryfoos, J.G. A community school in action. Reclaim. Children Youth 2003, 11, 203–206. [Google Scholar]

| School | Grade | Student Enrollment | Latino | Asian 1 | African American/Black | White | English Learners | Free/Reduced Price Lunch | Attendance Rate | Chronic Absence Rate | Suspension Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School A | TK-5 | 604 | 45% | 35% | 17% | 2% | 54% | 93% | 96% | 8% | 2% |

| School B | 6–8 | 574 | 34% | 45% | 17% | 2% | 35% | 96% | 96% | 11% | 13% |

| School C | 6–8 | 324 | 86% | 7% | 3% | 2% | 43% | 98% | 97% | 7% | 11% |

| School D | 6–12 | 473 | 88% | 1% | 11% | -- | 38% | 99% | 95% | 14% | 5% |

| School E | 9–12 | 2,092 | 19% | 19% | 36% | 22% | 8% | 54% | 94% | 15% | 5% |

| Health Clients and Visits | Health Visits by Type | Expanded Learning | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School | Student Clients | Student Visits | % Students Registered Clients | Mental Health | Medical | Health Education | First Aid | Dental | % Students Participating in Expanded Learning | Expanded Learning Attendance Rates |

| 2012–2013 | 2013–2014 | |||||||||

| School A | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | 48% | 96% |

| School B | 556 | 4426 | 88% | 11% | 19% | 8% | 46% | 17% | 70% | 93% |

| School C | 146 | 524 | 46% | 62% | 36% | 2% | --- | --- | 99% | 39% |

| School D | 334 | 1783 | 74% | --- | 46% | 14% | 9% | 31% | 99% | 87% |

| School E | 531 | 1675 | 27% | 26% | 46% | 12% | 16% | --- | 19% | 80% |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fehrer, K.; Leos-Urbel, J. “We’re One Team”: Examining Community School Implementation Strategies in Oakland. Educ. Sci. 2016, 6, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci6030026

Fehrer K, Leos-Urbel J. “We’re One Team”: Examining Community School Implementation Strategies in Oakland. Education Sciences. 2016; 6(3):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci6030026

Chicago/Turabian StyleFehrer, Kendra, and Jacob Leos-Urbel. 2016. "“We’re One Team”: Examining Community School Implementation Strategies in Oakland" Education Sciences 6, no. 3: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci6030026

APA StyleFehrer, K., & Leos-Urbel, J. (2016). “We’re One Team”: Examining Community School Implementation Strategies in Oakland. Education Sciences, 6(3), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci6030026