Comparative Effects of Esports and Traditional Sports on Motor Skills and Cognitive Performance in Higher Education Students in a Post-Pandemic Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Comparing the influence of esports activities with traditional sports activities on neurocognitive functions (attention and concentration) and motor skills among higher education students.

- Analyzing whether and how the effects of esports (which involve intense cognitive activity but less physical activity) differ from traditional sports (which involve physical activity and high motor coordination).

- Identifying the potential benefits or disadvantages of including esports activities in university educational programs compared to traditional sports activities, from the perspective of cognitive development (attention, concentration) and motor performance.

- Contributing with empirical data to substantiate educational policies regarding the integration of esports and traditional sports in the academic environment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

- In total, 31 students consistently participating in Esports (Esports group, denoted by E);

- In total, 32 students participating in traditional sports activities (traditional sports activities group, denoted by SA).

2.2. Study Design

- Stage I—The screening and selection process of participants (October–December 2024).

- Stage II—Assessment of motor skills (quantitative component) (February–March 2025).

- Muscle strength and speed—assessed by push-ups and standing long jump tests; 10 m sprint test;

- Coordination and balance—measured by the Flamingo Balance test and bilateral coordination tests;

- Posture and mobility—analyzed by the Sit and Reach test and static assessment of body posture.

- Stage III—Assessment of psychological dimensions (March–April 2025)

- Focused attention—tested by CRT (Choice Reaction Time).

- Short-term memory and information processing speed—tested by MRT (Working Memory Reaction Time).

- Stage IV—Data analysis

- Quantitative data were statistically processed by means of SPSS/(software version 26.0; IBM Corp., USA) using descriptive statistics, independent t-tests, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for group comparisons.

- Methodological justification

- Standardized tests ensure objectivity and comparability of motor and cognitive performance, bringing depth and context, and highlighting how students perceive the benefits and limitations of each activity.

2.3. Procedure

- Preparatory stage

- Day 1: physical assessment using the Alpha-Fit Test Battery;

- Day 2: psychological assessment of attention and concentration.

- Physical assessment—Alpha-Fit Test Battery

- Body mass index (BMI)—determined by the weight/height2 ratio;

- Upper limb strength (40 s push-ups)—maximum number of correctly performed repetitions;

- Abdominal strength (30 s repetitions)—a standardized sit-up test;

- Static balance—the Flamingo Balance test is used to measure the duration (in seconds) of holding the single-leg stance;

- Movement speed—measured by a 20 m sprint race timed with a CASIO HS-80TW-1EF stopwatch;

- Body posture—visually assessed bilaterally (upper and lower limbs) and scored on a scale of 1 (poor posture) to 5 (correct posture). A rough estimate of the posture and functional mobility of shoulder-neck region. The tester estimates the restrictions of functional movement by observing the final position of the hands against the wall. Result is separately scored for the right and left sides.

- Experimental conditions and control of variables

- All tests were conducted between 9:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m. to avoid diurnal variations in performance and depended on the participants’ availability.

- Participants were asked to avoid strenuous activities and caffeine consumption 24 h prior to testing.

- The order of tests was identical for all participants (physical tests followed by cognitive tests).

- All equipment was calibrated daily.

- Examiners followed a uniform protocol, and the same instructions were communicated to all participants.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

- Descriptive indicators: means, standard deviations, coefficients of variation;

- Comparison tests: t-test for independent samples (esports vs. sports activities), with significance at p < 0.05;

- Although Shapiro–Wilk tests indicated departures from normality for several variables, independent-samples t-tests were retained due to their documented robustness under moderate normality violations, particularly in balanced group designs. Visual inspection of distributions did not reveal severe deviations. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were reported to quantify the magnitude of observed differences, consistent with recommendations for transparent reporting.

- Correlation analyses (Pearson’s r) to examine the relationships between motor performance and cognitive reaction times.

3. Results

- (a)

- Esports group (N = 31):

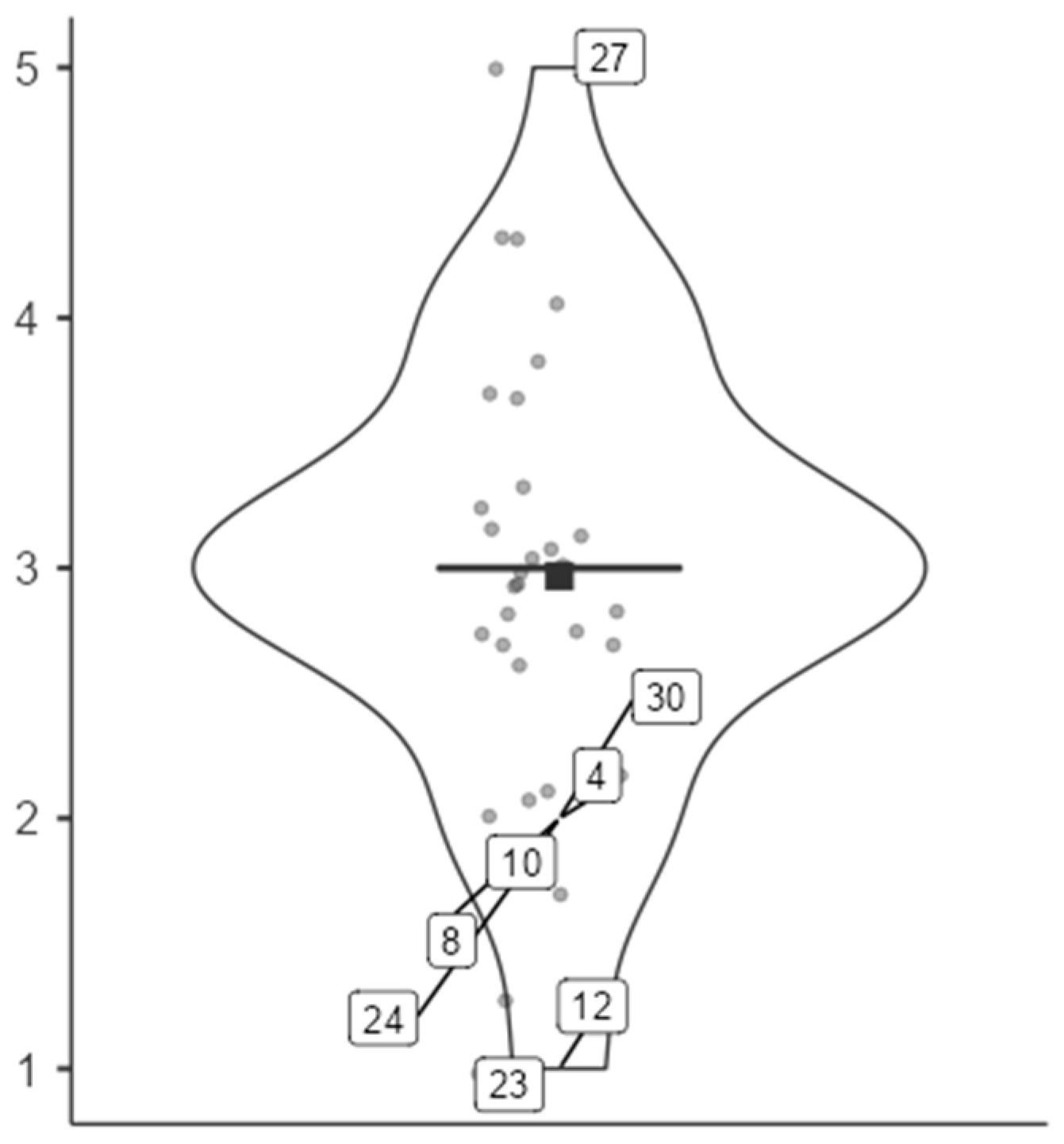

- The mean score for reaction speed is M = 2.97 (SD = 0.87), indicating a moderate level (Figure 1).

- Choice reaction time (M = 2.19) and working memory reaction time (M = 3.29) suggest average-to-good cognitive speed, with a slight tendency toward interindividual variability (Figure 2).

- Posture (right/left) has high means (M = 4.65–4.71), but the distributions are negatively asymmetric (Skewness < −2) and with very high Kurtosis (>3), indicating a concentration of scores at the maximum level—most participants had correct posture.

- The mean score for balance is 68.3 s (SD = 36.5), which indicates high variability among participants, suggesting that body stability differs considerably.

- Movement speed (M = 5.29 s) and abdominal strength (M = 21.2 repetitions) are within normal limits, but upper limb strength (push-ups, M = 15.6) is lower compared to the sports group.

- (b)

- Traditional sports activities group—SA (N = 32):

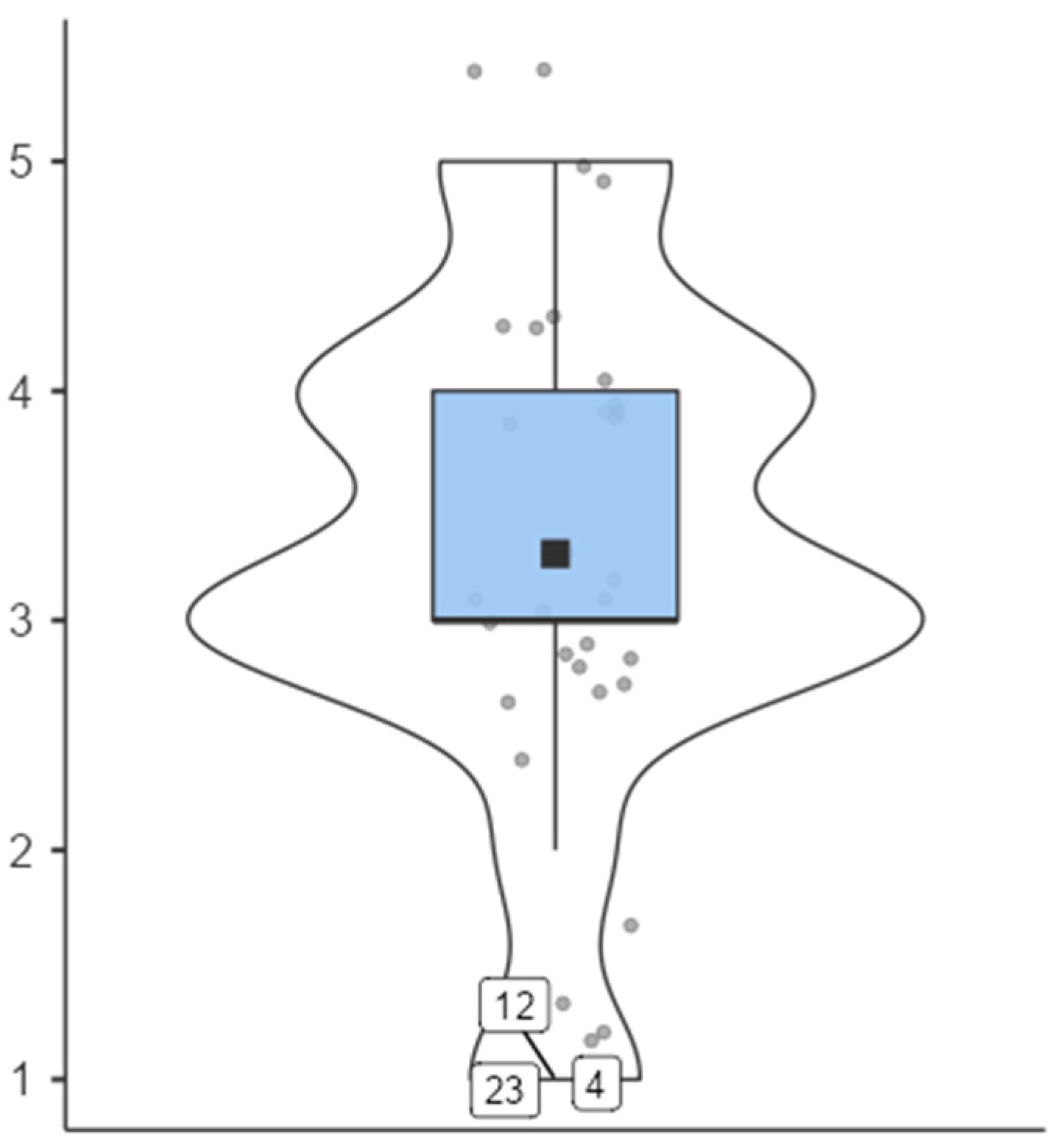

- Choice reaction time (M = 2.31) and working memory reaction time (M = 3.44) have values close to those of the esports group, indicating similar cognitive performance for the two groups.

- Body posture has almost maximum values (M = 4.91 right; M = 4.97 left), reflecting superior postural alignment compared to esports participants.

- Average movement speed is slightly higher (M = 5.02 s vs. 5.29 s for the esports group), confirming better motor efficiency in traditional athletes.

- Abdominal strength (M = 23.2) and upper limb strength (push-ups, M = 18.2) are significantly higher than in the esports group, suggesting better overall physical fitness.

- Most variables do not follow a normal distribution (p < 0.05), especially for variables related to posture (W = 0.334–0.544), reaction time, and age.

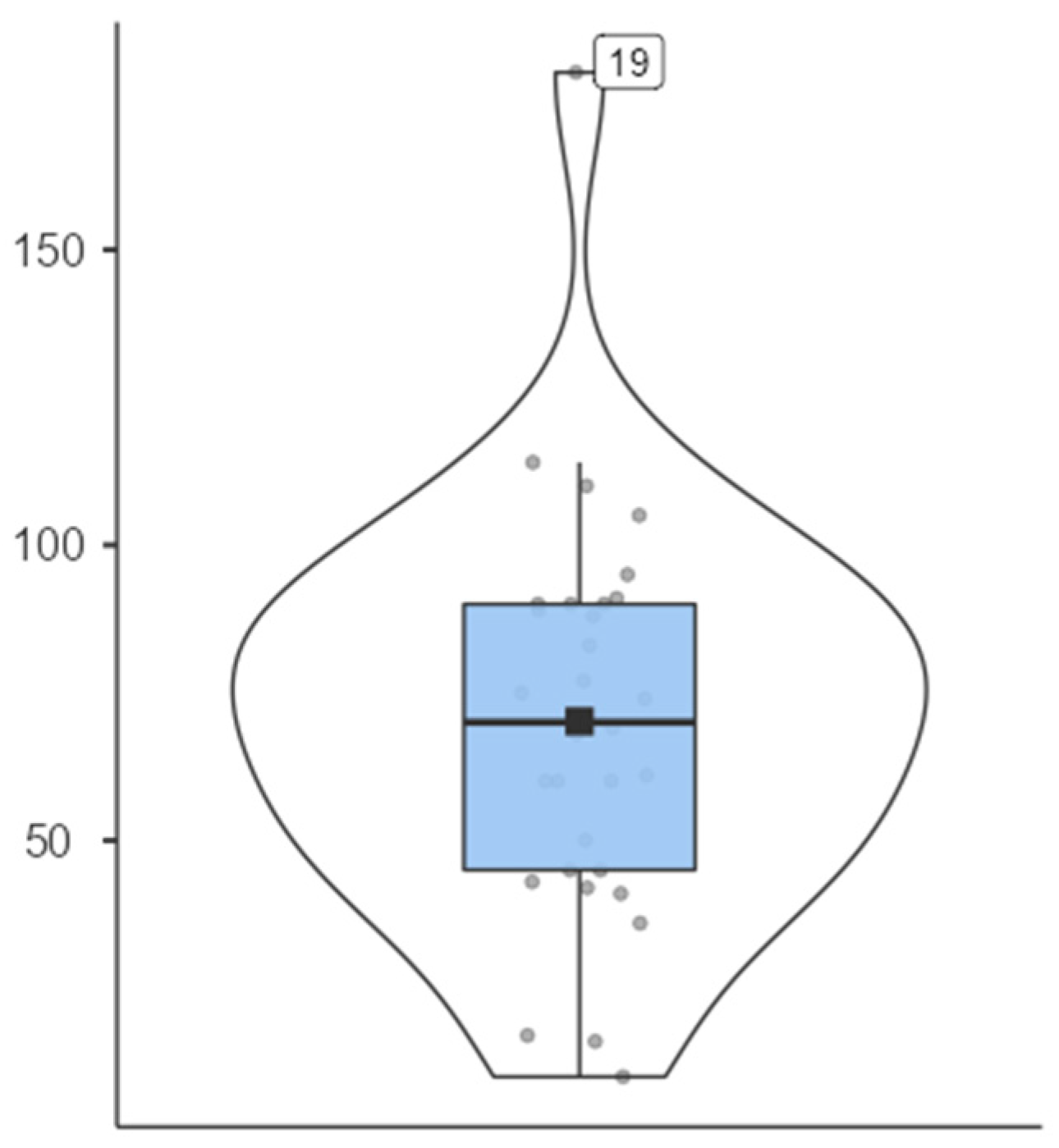

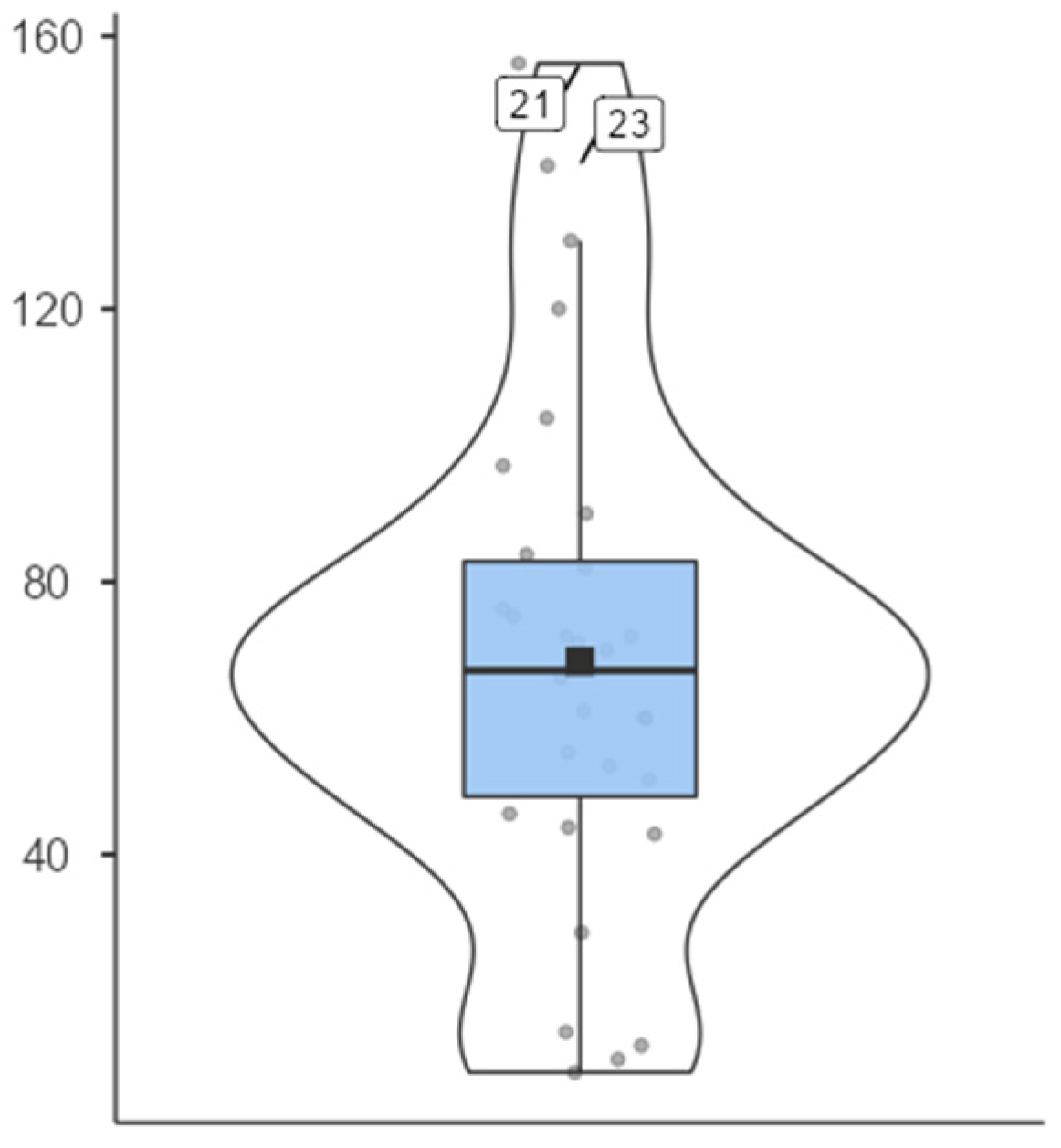

- For the E_Balance, E_Speed, E_Sit-ups, SA_Balance, SA_Speed, SA_Sit-ups, SA_Push-ups variables, p > 0.05, which suggests an approximately normal distribution, allowing the use of parametric tests (t-test).Figure 3. Static balance (SA).Figure 4. Static balance (E).Table 1. Descriptive statistics for E and SA groups.

Variables N Missing Mean Median Std Dev Min Max Skewness Std. Error Skewness Kurtosis Std. Error Kurtosis Shapiro-

Wilk WShapiro-

Wilk pE_IMC 31 1 24.8 24.5 2.84 19.5 30 −0.213 −0.798 0.965 0.387 −0.213 −0.798 E_Reaction speed 31 1 2.97 3 0.875 1 5 −0.254 0.421 0.721 0.821 0.872 0.002 E_CRT 31 1 2.19 2 1.01 1 5 1.02 0.421 0.91 0.821 0.833 <0.001 E_MRT 31 1 3.29 3 1.1 1 5 −0.465 0.421 0.125 0.821 0.887 0.003 E_Posture

Right31 1 4.65 5 0.755 2 5 −2.27 0.421 4.78 0.821 0.544 <0.001 E_Posture

Left31 1 4.71 5 0.643 3 5 −2.08 0.421 3.02 0.821 0.501 <0.001 E_Balance 31 1 68.3 67 36.5 8.1 156 0.47 0.421 0.31 0.821 0.958 0.252 E_Speed 31 1 5.29 5.2 0.447 4.6 6.11 0.323 0.421 −1.02 0.821 0.946 0.119 E_Sit-ups 31 1 21.2 22 4.37 13 30 −0.121 0.421 −0.8 0.821 0.97 0.529 E_Push-ups 31 1 15.6 15 4.18 9 27 0.923 0.421 1.17 0.821 0.918 0.021 E_Age 31 1 19.7 20 0.653 19 21 0.436 0.421 −0.612 0.821 0.771 <0.001 AS_IMC 32 0 25.3 25.2 3.27 18.9 32.5 0.176 0.142 0.978 0.747 0.687 AS_ Reaction speed 32 0 3.13 3 0.907 2 5 0.0173 0.414 −1.26 0.809 0.833 <0.001 AS_CRT 32 0 2.31 2.5 0.859 1 4 −0.349 0.414 −0.99 0.809 0.823 <0.001 AS_MRT 32 0 3.44 3.5 1.13 2 5 0.0232 0.414 −1.39 0.809 0.856 <0.001 AS_ Posture

Right32 0 4.91 5 0.296 4 5 −2.93 0.414 7 0.809 0.334 <0.001 AS_Posture

Left32 0 4.97 5 0.177 4 5 −5.66 0.414 32 0.809 0.172 <0.001 AS_Balance 32 0 70.2 70 33.6 10 180 0.818 0.414 2.5 0.809 0.941 0.078 AS_Speed 32 0 5.02 5 0.42 4.2 6.1 0.593 0.414 0.695 0.809 0.956 0.207 AS_Sit-ups 32 0 23.2 23 4.48 15 30 0.0317 0.414 −1.03 0.809 0.947 0.122 AS_Push-ups 32 0 18.2 17 5.07 10 29 0.459 0.414 −0.605 0.809 0.96 0.275 AS_Age 32 0 19.8 20 0.803 18 21 0.0996 0.414 −0.692 0.809 0.853 <0.001 Table 2. Comparative values between the Esports (E) group and the traditional sports activities (SA) group.Table 2. Comparative values between the Esports (E) group and the traditional sports activities (SA) group.Variable M Esports SD Esports M SA SD SA t p Cohen’s d

0.000Interpretation Reaction speed 2.97 0.88 2.97 0.88 0.00 1.000 no difference Reaction time—choices 2.19 1.01 2.31 0.86 −0.51 0.613 −0.13 small, insignificant effect Reaction time—memory 3.29 1.10 3.44 1.13 −0.53 0.596 −0.13 small, insignificant effect Posture—right 4.65 0.76 4.91 0.30 −1.81 0.075 −0.46 medium, insignificant effect Posture—left 4.71 0.64 4.97 0.18 −2.20 0.031 −0.56 medium, significant effect Balance (s) 68.3 36.5 70.2 33.6 −0.22 0.830 −0.05 no difference Speed (s) 5.29 0.45 5.02 0.42 2.47 0.016 0.62 medium, significant effect Sit-ups/30 s 21.2 4.37 23.2 4.48 −1.79 0.078 −0.45 medium, insignificant effect Push-ups/40 s 15.6 4.18 18.2 5.07 −2.22 0.030 −0.56 medium, significant effect - Information processing speed and reaction time (choices, working memory):

- Body posture:

- Physical and motor skills (balance, speed, strength):

- Balance: No differences were found between groups (p = 0.83), indicating that basic postural stability is comparable, possibly due to the visuo-motor involvement also present in esports.

- Speed: Significantly better in athletes engaged in traditional sports activities (p = 0.016, d = 0.62).

- Abdominal and upper limb strength: Insignificant differences for sit-ups (p = 0.078) and significant differences for push-ups (p = 0.030).

- Non-significant group differences should not be interpreted as evidence of equivalence; rather, they indicate that no statistically detectable differences were observed within the limits of the present sample and analytical approach.

- Effect size (Cohen’s d):

- Correlation:

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Archibald, S. (2024). Examining the impact of Esports program on higher education: A systematic literature review. Issues in Information Systems, 25(3), 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R. (2006). Physical education and sport in schools: A review of benefits and outcomes. Journal of School Health, 76(8), 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bányai, F., Griffiths, M. D., Király, O., & Demetrovics, Z. (2020). The psychology of esports: A systematic literature review. Journal of Gambling Studies, 35(2), 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boot, W. R., Kramer, A. F., Simons, D. J., Fabiani, M., & Gratton, G. (2008). The effects of video game playing on attention, memory, and executive control. Acta Psychologica, 129(3), 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delello, J., McWhorter, R., Yoo, S., Roberts, P., & Adele, B. (2025). The impact of esports on the habits, health, and wellness of the collegiate player. Journal of Intercollegiate Sport, 18(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFrancisco-Donoghue, J., Balentine, J., Schmidt, G., & Zwibel, H. (2019). Managing the health of the eSport athlete: An integrated health management model. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 5(1), e000467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., & Payne, W. R. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for adults: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekefjärd, S., Piussi, R., & Hamrin Senorski, E. (2024). Physical symptoms among professional gamers within eSports, a survey study. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, 16, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. D., & Nuyens, F. (2017). An overview of structural characteristics in problematic video game playing. Current Addiction Reports, 4(3), 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamari, J., & Sjöblom, M. (2017). What is eSports and why do people watch it? Internet Research, 27(2), 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrysomallis, C. (2011). Balance ability and athletic performance. Sports Medicine, 41(3), 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imanian, M., Khatibi, A., Sousa, C. V., Heydarinejad, S., Veisia, E., & Saemi, E. (2025). Effects of electronic sports on the cognitive skills of attention, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Perceptual and Motor, 132(2), 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenny, S. E., Manning, R. D., Keiper, M. C., & Olrich, T. W. (2017). Virtual(ly) athletes: Where eSports fit within the definition of “sport”. Quest, 69(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, D., & Spradley, B. D. (2017). Recognizing esports as a sport. The Sport Journal, 19, 1–10. Available online: https://thesportjournal.org/article/recognizing-esports-as-a-sport/ (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- King, D., & Esports Medicine Team. (2023). Q & A: Top esports injuries and how to prevent them. Cleveland Clinic. Available online: https://consultqd.clevelandclinic.org/qa-top-esports-injuries-and-how-to-prevent-them (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Kowal, M., Toth, A. J., Exton, C., & Campbell, M. J. (2018). Different cognitive abilities displayed action video gamers and non-gamers. Computers in Human Behavior, 88, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, M., Klichowski, M., Serweta-Pawlik, A., Rosciszewska, A., & Żurek, G. (2025). Effects of short- and long-term virtual reality training on concentration performance and executive functions in amateur esports athletes. Virtual Reality, 29, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz, M., Żurek, A., Jamro, D., Serweta-Pawlik, A., & Żurek, G. (2024). Changes in concentration performance and alternating attention after short-term virtual reality training in E-athletes: A pilot study. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 8904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, W.-K., Liu, R.-T., Chen, B., Huang, X., Yi, J., & Wong, D. W.-C. (2022). Health risks and musculoskeletal problems of elite mobile esports players: A cross-sectional descriptive study. Sports Medicine—Open, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leth-Steensen, C., Elbaz, Z. K., & Douglas, V. I. (2000). Mean response times, variability, and skew in the responding of ADHD children: A response time distributional approach. Acta Psychologica, 104(2), 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y., Hutchinson, J. C., O’Connell, C. S., & Sha, Y. (2022). Reciprocal effects of esport participation and mental fatigue among Chinese undergraduate students using dynamic structural equation modeling. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 62, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H., He, H., Hou, X., Wang, J., & Chi, L. (2024). Cognitive expertise in e-sport experts: A three-level model meta-analysis. PeerJ, 12, e17857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musick, G., Zhang, R., McNeese, N. J., Freeman, G., & Hridi, A. P. (2021). Leveling up teamwork in esports: Understanding team cognition in a dynamic virtual environment. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(CSCW1), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naglieri, J. A., & Otero, T. M. (2024). PASS Theory of Intelligence and its measurement using the Cognitive Assessment System, 2nd edition. Journal of Intelligence, 12(8), 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newzoo. (2021). Newzoo’s global esports and live streaming market report 2021. Available online: https://newzoo.com/resources/trend-reports/newzoos-global-esports-live-streaming-market-report-2021-free-version (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Onate, J. A., Edwards, N. A., Emerson, A., Maymir, C. L., Kraemer, W. J., Fogt, N., Fogt, J. S., & Conroy, S. (2023). Normative performance profiles of college-aged esport athletes in a pilot study. International Journal of Esports, 2023, 75. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10786200/ (accessed on 26 January 2026). [PubMed]

- Pedraza-Ramírez, I., Sharpe, B. T., Behnke, M., Toth, A. J., & Poulus, D. R. (2025). The psychology of esports: Trends, challenges, and future directions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 81, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelin, F., Radmann, A., Mitrache, G., Ciolcă, C., Predoiu, R., & Săftel, A. M. (2020). The role of physical education activities at motor and psychological levels-teachers’ perception. Discobolul-Physical Education, Sport & Kinetotherapy Journal, 59, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perret, C., & Müller, C. (2021). Physical activity and health promotion in esports and gaming: Challenges of sedentary behaviour and screen time. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3, 693700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzo, A. D., Na, S., Baker, B. J., Lee, M. A., Kim, D., & Funk, D. C. (2018). eSport vs. sport: A comparison of spectator motives. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 27(2), 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluhar, E., McCracken, C., Griffith, K. L., Christino, M. A., Sugimoto, D., & Meehan, W. P., III. (2019). Team sport athletes may be less likely to suffer anxiety or depression than individual sport athletes. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 18(3), 490–496. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6683619/ (accessed on 26 January 2026).

- Reardon, C. L. (2021). The mental health of athletes: Recreational to elite. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 20(12), 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, K., Soffner, M., Bickmann, P., Froböse, I., Tholl, C., Wechsler, K., & Grieben, C. (2022). Media consumption, stress and well-being of video game and esports players in Germany: The eSports study 2020. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schary, D. P., Jenny, S. E., & Koshy, A. (2022). Leveling up eSports health: Current status and call to action. International Journal of eSports, 2, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Vasile, A. I., Chesler, K., Velea, T., Croitoru, D., & Stănescu, M. (2024). Witty sem system and cognitrom assessment system: Novel technological methods to predict performance in youth rock climbers. Annals of Applied Sport Science, 12(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visu-Petra, G., Miclea, M., & Visu-Petra, L. (2012). Reaction time-based detection of concealed information in relation to individual differences in executive functioning. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26(3), 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D. E. R., Nicol, C. W., & Bredin, S. S. D. (2006). Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 174(6), 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weed, M., & Bull, C. (2009). Sports tourism: Participants, policy and providers (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Witkowski, E. (2012). On the digital playing field: How we “do sport” with networked computer games. Games and Culture, 7(5), 349–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K., Zi, Y., Zhuang, W., Gao, Y., Tong, Y., Song, L., & Liu, Y. (2020). Linking esports to health risks and benefits: Current knowledge and future research needs. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 9(6), 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X., Hu, Y., Matic, R. M., & Popovic, S. (2025). Esports physical exercise/performance matrix 1.0 country factsheets: Results and analyses from Serbia. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1526297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Esports | Traditional Sports |

|---|---|---|

| Attention and focus | High; develop reaction speed and rapid decision-making | Moderate to high; trained through coordination and tactical adaptation |

| Motor coordination | Limited, predominantly fine (eye-hand) | Developed, involving all body segments |

| Posture and physical fitness | Poor, increased risk of sedentary lifestyle | Enhanced, supporting overall health and tone |

| Social and collaborative development | High in online teams, but with indirect interaction | High, through direct contact and group cohesion |

| Risk of digital addiction or stress | High, if not regulated | Low, associated with psychological well-being |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Leonte, N.; Hainagiu, S.; Neagu, N.; Fleancu, L.J.; Popescu, O. Comparative Effects of Esports and Traditional Sports on Motor Skills and Cognitive Performance in Higher Education Students in a Post-Pandemic Context. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020222

Leonte N, Hainagiu S, Neagu N, Fleancu LJ, Popescu O. Comparative Effects of Esports and Traditional Sports on Motor Skills and Cognitive Performance in Higher Education Students in a Post-Pandemic Context. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(2):222. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020222

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeonte, Nicoleta, Simona Hainagiu, Narcis Neagu, Leonard Julien Fleancu, and Ofelia Popescu. 2026. "Comparative Effects of Esports and Traditional Sports on Motor Skills and Cognitive Performance in Higher Education Students in a Post-Pandemic Context" Education Sciences 16, no. 2: 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020222

APA StyleLeonte, N., Hainagiu, S., Neagu, N., Fleancu, L. J., & Popescu, O. (2026). Comparative Effects of Esports and Traditional Sports on Motor Skills and Cognitive Performance in Higher Education Students in a Post-Pandemic Context. Education Sciences, 16(2), 222. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16020222