1. Introduction

Throughout the “culture of digitality” (

Stalder, 2021), new (digital) spaces of possibility are constantly being created, which simultaneously expand and restrict the digital possibilities of students.

Stalder (

2021) distinguished three dimensions of digitality: referentiality, communality, and algorithmicity. In the first dimension individuals search for orientation within these new (digital) spaces and must take responsibility for selecting and passing on references. New forms of social interaction are indispensable in the second dimension, whereby the individual increasingly defines themselves by way of personal social networks that possess a stable yet delicate quality. In the third dimension, machine and automated processes already contribute to a pre-selection of information that controls and guides the cultural practices of students (

Stalder, 2021, pp. 144–166). In order to be able to deal with the resulting uncertainties and challenges, students need to become familiar with digital competencies that can be acquired by taking advantage of three types of learning opportunities in the university context: In (1)

formal teaching and learning contexts, for example, teaching and learning content is worked on together with the students in didactically structured university seminars. These formal teaching and learning contexts are “institutionalized, intentional and planned through public organizations” (

UNESCO, 2012, p. 11). In addition, depending on the financial, personnel and infrastructural resources of the university, students can choose from a variety of (2)

nonformal learning contexts, for example, by participating in interdisciplinary workshops to further develop their digital competencies (

Breitschwerdt et al., 2025, p. 109). Students also can engage in a wide range of

informal learning activities (3), which are not defined by a specific learning outcome, do not lead to any certification (

Werquin, 2009), and are less organized and structured than both formal and nonformal education. Informal learning encompasses activities that take place within the family, the workplace, the local community, or in everyday life, and may occur in self-directed, family-directed, or socially directed ways (

UNESCO, 2012).

Current theoretical approaches point to the increasing blending of formal, nonformal and informal contexts, suggesting a mutual conditionality of these learning formats that renders a clear distinction impossible (

Rosemann, 2025a). In this context, various authors emphasize the importance of analyzing the interplay between formal and informal learning contexts within organizational settings (e.g.,

Tannenbaum et al., 2024;

Boerma et al., 2025) and highlight the growing interconnectedness of learning and educational spaces as well as the dimension of time and space (

Kraus, 2022). Learners continuously move between different learning contexts and times, which can dynamize and situationally influence the development of digital competencies. It is evident that students’ digital learning and usage practices vary depending on the context (

Rosemann, 2025b) and time (

Schwarz et al., 2021). This is particularly evident in university contexts, where formal and nonformal structures, as well as informal learning activities, interact in a unique way, simultaneously supporting and challenging learning processes. Recent studies highlight that these variations are not only due to individual preferences but also shaped by broader structural conditions, including socio-economic factors and access to digital resources (

Tang et al., 2025).

Students have access to numerous, partly non-transparent learning opportunities, which can be situated along a continuum of formality and digitality and may initiate digital competence development processes to varying degrees (

Rosemann, 2025a). It is well known that students display varying levels of digital competence (

Biehl & Besa, 2021;

Zinn et al., 2022), use different numbers of digital technologies (

Schmidt-Lauff et al., 2022), and use them mainly for entertainment (

Bond et al., 2018, p. 1ff.). However, these forms of use do not necessarily translate into competence development. Accordingly, students primarily develop digital competencies in study-related formal teaching and learning contexts, for example, when working on self-study assignments or module completion tasks (

Rosemann, 2025b). This indicates that these differences not only result from individual preferences but are also shaped by broader structural conditions. Research suggests that these structural conditions, including differential access to technology and support, can have substantial consequences for student outcomes, even contributing to dropout rates in higher education (

Barragán Moreno & Guzmán Rincón, 2025). In academic and public discourse, various socio-demographic and economic factors that influence the use of digital media and reproduce social inequalities are subsumed under the concept of the “digital divide” (

Norris, 2001). Against this background,

J. van Dijk (

2020) identifies four factors that guide the acquisition of digital skills. The first factor is an individual’s attitude toward operating a digital device, considered a fundamental prerequisite for the use of digital media. The second factor addresses physical access, and this means “the opportunity to use digital media by obtaining them privately in homes or publicly in collective settings” (

J. van Dijk, 2020, p. 48). Against this background, he distinguishes between material access and conditional access. The former is broader than physical access and includes subscriptions, peripheral equipment, electricity, software, and printed materials. The latter is a more limited concept and refers to provisional access to particular applications, programs, or content on computers. The third factor consists of media- and content-related digital skills that “focus on what users can actually do with and in digital media” (

J. van Dijk, 2020, p. 66). The last factor refers to the actual usage of digital media, which guides the development of digital competence through a corresponding regularity. Of central importance are the intensity of use, the diversity of use, and the type of activities involved (

J. van Dijk, 2020, pp. 34–96).

This culture of digitality thus gives rise to various practices of situational, learning-relevant engagement with digital media, which vary according to contextual conditions such as the availability of devices, formal and informal learning structures, and temporal constraints. Via subject-theoretical learning theory, which originates from the tradition of German Critical Psychology, these practices can become recognizable when students encounter experiences of discrepancy (

Holzkamp, 1995) within the continuum of learning contexts (

Rosemann, 2025a), which are perceived as learning occasions and can trigger digital competence development processes. This theoretical perspective underlines the rationale for focusing on both students’ physical access to digital media and the actual learning and usage practices of students.

The multidimensional model of

J. van Dijk (

2020) provides the basis for this study to analyze the specific learning and usage practices of students dealing with digital media in varying situations. Accordingly, it is essential to consider learning activities not in isolation, but always in interaction with contextual factors. In view of the relevance of informal digital learning practices for the development of digital competencies (

Rosemann, 2025b), this article focuses on the interrelationship between two factors of the multidimensional model of

J. van Dijk (

2020): physical access to digital media (factor 2) and the digital learning and usage practices of students (factor 4). The aim is to determine how much each of the reciprocal factors contributes to explaining the perception of learning-relevant situations using regression analyses. The entry point of this digital learning and usage diary study is a multi-method research project (DigiTaKS*). Here, 70 students from three student cohorts (2021, 2022, 2023) in the Humanities and Social Sciences at the Helmut-Schmidt-University, Hamburg

1, participated in a 10-day learning and usage diary study. On the one hand, quantitative surveys are used to identify students’ study-, leisure- and media-related activities, while on the other, documentation is used to locate learning-relevant situations in everyday student life that can be used as impulses for the promotion of digital skills. The investigation is centered around the questions of what the relative contributions of the factors (physical access to digital media and practices related to the use of digital media for learning) to explaining the perception of learning-relevant moments in everyday academic life are, and what conclusions can be drawn from this for the learning-supportive design of study programs and (individual) learning environments. The results of our diary study show that it is not merely the possession of digital devices, but above all their flexible, reflective, and critical use across the continuum of learning contexts that is crucial for perceiving learning-relevant situations. These findings highlight the need to design university programs and learning environments in ways that promote active learning practices and reflection to strengthen the development of digital competencies.

Firstly, the article examines the digital learning and usage practices of students from a practical and subject-theoretical perspective, before the next section—following the logic of the continuum model of learning forms (

Rosemann, 2025a)—presents the state of research on formal, nonformal, and informal digital learning practices in higher education (

Section 2). Subsequently, the learning and usage diary study is presented in detail with regard to its objectives, methodology, implementation, and analysis (

Section 3). As part of the analysis, descriptive results regarding students’ physical access to digital media are first examined. Subsequently, the longitudinal diary data are analyzed to identify activities, and based on these, to consolidate them into practice-oriented patterns of learning-related digital media use via factor analysis (

Section 4). The presentation of the results concludes with the reporting of the multivariate regression analyses (

Section 5). Finally, a discussion of the results and a critical reflection on the research design is conducted (

Section 6).

4. Descriptive and Analytical Results of Students’ Digital Learning Practices

The descriptive results are presented here to offer an insight into the characteristics of the student population. The conditions of everyday study life are then outlined based on the entrance survey, prior to describing the media-, study- and leisure-related activities of the students during of the diary study. Building on this, the practices of learning-related use of digital media identified through factor analysis are outlined. Subsequently, challenging learning situations reported during the two-week data collection period are described as triggers for learning-related use of digital media, as they can provide impulses for the further development of digital competencies. Finally, the results of the multivariate linear regression analyses are presented to determine the relative contribution of the two central factors (physical access to digital media and practices of learning-related use) to the frequency of perceiving learning-relevant situations.

4.1. Characteristics of the Sample

The majority of students in the sample are male (58%). The relatively high proportion of men in this sample, comparable to other surveys in the higher education sector (

Destatis, 2026), could be related to the students’ institutional affiliation with the Helmut-Schmidt-University, Hamburg. On average, the students are 23 years old, and 30% have a migration background. With regard to the age- and migration-specific composition of the sample, it can be stated—drawing on the findings of the

Author Group for the Education Report (

2024) and the German Student Survey (

Kroher et al., 2023)—that the distribution within the sample aligns comparatively well with the demographic composition of young adults in Germany.

In addition, 96% of students have a general higher education entrance qualification and 4% have a comparable qualification. The descriptive results also demonstrate that 25% of students had already started vocational training before beginning their bachelor’s degree program, and 38% had previous study experience. This indicates heterogeneous and non-linear educational pathways within the present sample, which may be associated with differences in learning experiences. The students come from three different subject areas of the Humanities and Social Sciences: the majority (44%) study education and educational science, followed by 29% from history and 28% from psychology. In addition to their studies, an above-average number of students are involved in voluntary work in clubs and projects. Accordingly, 35% of those surveyed reported voluntary work, with the majority being active in the social sector, followed by students who are involved in religious organizations. This finding also indicates an approximately feature-specific representativeness of students who engage in volunteer activities. In 2024, 40% of 14- to 29-year-olds were involved in voluntary work, according to the representative Volunteer Survey (

Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth, 2024). Furthermore, only an extremely small proportion of students (1%) reported caring for relatives or children.

The students’ affiliation with the Humanities and Social Sciences is associated with specific disciplinary cultures (e.g., text-oriented work, analytic tasks), which are largely comparable across the fields represented in this study. At the same time, the present sample exhibits a heterogeneous composition with regard to prior educational and study experiences. It can therefore be assumed that students may differ in their previously acquired digital learning and usage practices as well as in their temporal usage profiles—differences that should be considered when interpreting the results. Moreover, a notable proportion of students engage in voluntary activities, which may be associated with more structured daily routines.

4.2. Spatial Framework Conditions

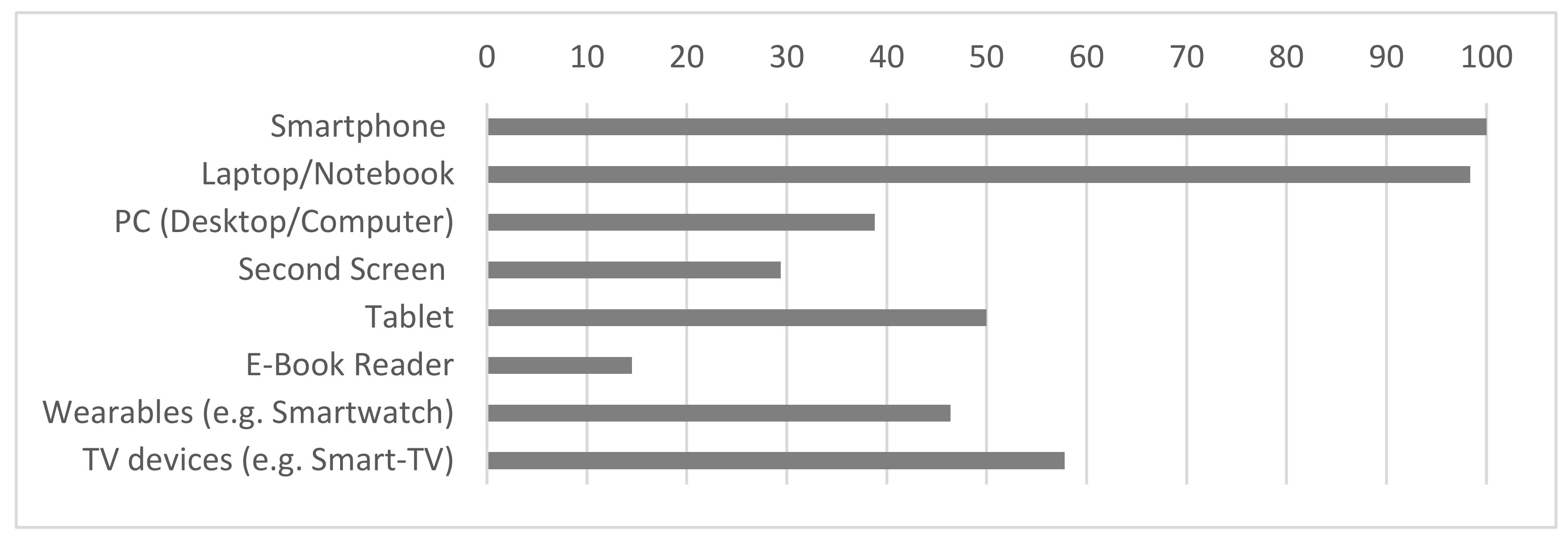

Students’

social practices are primarily guided by smartphones (100%), laptops (98%), and tablets (50%) (

Figure 1). The findings of the initial survey reveal that students own these mobile devices most frequently. In contrast, PCs (39%), TV devices (46%), and wearables (46%) are owned by a portion of students but are used overall significantly less frequently than smartphones and laptops. Strikingly, students have a wide range of devices in their individual learning environments. Accordingly, students report owning an average of 4.1 total digital media, although there are differences in the frequency of use and the respective reasons for use depending on the context.

The descriptive results provide the first cautious indications of some specifics in the individual equipment of students with digital media. Accordingly, mobile devices such as smartphones, laptops, and tablets appear to be central components of everyday study life. These offer sufficient flexibility to manage both intensive individual work phases in a private setting and to accompany active participation in formal courses. In contrast, static digital media such as the desktop computer and a second screen offer limited flexibility in terms of location and tend to play a subordinate role in students’ social–learning practices. The latter appear to be favored only by a specific group of users within the student population—namely those who rely on a fixed desktop computer and an additional external monitor. This subgroup tends to work in more technically equipped, stationary study environments, which makes the use of such tools particularly convenient and integral to their study routines.

4.3. Temporal Scope of the Students’ Activities

The findings regarding the organization of social practice provide initial indications of some person-specific preferences in the usage of digital media, which could be due to individual preferences and interests, yet no conclusions should be drawn from this cross-sectional data about the daily intensity of use digital media. Hence, the subjective assessments of the amount of time spent on activities, which originate from the diary study, are used in the following analysis step.

The

daily use of digital media (

Table 2) shows that students spend the most time using their DigiTaKS* laptops, averaging 143 min a day, followed by their private laptops at 116 min. Tablets are also used quite frequently during studies, averaging 94 min, to take notes, complete study-related tasks, or to study for exams. Smartphones are primarily used for communication with others in a time- and location-flexible manner, in addition to checking and replying to emails and short-term research activities. In this context, students report spending an average of 45 min a day on study-related smartphone use. Here, the standard deviations of the amount of time spent using a second screen and private laptops indicate considerable variance. This reaffirms the assumption that among the study population, different user groups can be identified, characterized by significant variances in the design of their individual learning environments. In contrast, slightly lower standard deviations are evident for the use of tablets and smartphones. Accordingly, these digital media appear to have a similar extent of use across the entire student population.

To gain a more detailed insight into

study-related activities (

Table 3), students were asked to estimate the amount of time they spent on activities that arose in the context of their studies. The results show that by far the most time is spent on attending courses (M = 158 min), followed by exam preparation (M = 100 min). This is followed by self-study or reading texts, with an average of 84 min per day. In contrast, students invest less time in completing module work and preparation of term papers (in each case 79 min a day on average). These are not necessarily graded, but they are mandatory requirements that may be prerequisites for admission to an examination or for successful completion of a module.

A look at the standard deviations reveals that the amount of time spent attending events differs considerably between days. These strong variances can possibly be attributed to the fact that both study days and days off were included in the learning and usage diary study. In contrast, the standard deviations are low for self-study/reading and exam preparation. These appear to be of roughly constant importance over the study population.

For

leisure-related activities (

Table 4), the results indicate that students need the most daily time for meetings with other students (M = 157.9 min) and recovery activities such as regeneration (M = 145.5 min). This is followed by voluntary activities, with an average of 123.7 min per day, and sporting activities, with an average of 102.4 min per day.

The largest standard deviation is located in the daily amount of time spent meeting with other students and in voluntary activities. This could indicate considerable intra- and inter-individual variance within the student population for these activities. Intra-individual differences refer to variations in a single student’s behavior across different days or situations, while inter-individual differences refer to variations between different students. It can be assumed that the intensity of the subjectively estimated time spent on each activity differs not only between students but also varies from day to day for the same activity. In contrast, less variation occurs within the student group for sporting activities.

4.4. Practices of Learning-Related Use of Digital Media

Considering the results of the learning and usage diary study, it was possible to gain initial insights into the daily intensity of use and the specific occasions for using differentiated digital media. Exploratory factor analyses were used to work out practices for dealing with digital media. The decision was deliberately made to include digital media available to students in their individual learning environments (possessions of digital media) and the study-, media-, and leisure-related activities (average frequency of activities over a 10-day survey period) in the analysis. This was performed to interlink the two levels and thus elaborate on the latent structures of the observational variable. Specifically, the data from the second (2022) and third (2023) survey waves, which were based on the modifications to the short questionnaire after the first survey wave, were considered. The prerequisites for the factor analysis were checked using the following tests: the KMO criterion and the Bartlett test for sphericity (

Bühner, 2011, p. 346). In addition, individual activities were excluded from the analysis considering the anti-image matrices (

Kaiser, 1976). Thus, a total of nine activities were included in the factor analysis.

The use of principal component analysis resulted in a three-factor solution, which was subsumed into the following practices based on an interpretation of the content: mobile usage practices in the formal teaching and learning context (Factor 1), regular study- and leisure-related practices (Factor 2), and module completion practices (Factor 3).

Overall, the factor loading matrix has a simple structure; in other words, the variables only ever load onto one factor (

Backhaus et al., 2018, p. 399), with the proportion of explained variance being 52%. Therefore, the following specifics can be identified for the digital media use practices:

Mobile usage practices in the formal teaching and learning context (Factor 1) are directly related to preparation and follow-up work as well as active participation in study-related courses. In this context, students predominantly use mobile devices such as laptops and tablets to prepare for and follow up on study-related courses at their private desks, in addition to taking notes in the immediate course context. These mobile devices offer strong spatial flexibility, allowing users to use them almost anywhere, not requiring a fixed location or workplace.

Regular study- and leisure-related practices (Factor 2) include reading texts, carrying out research activities, and completing module assignments. These can be carried out as individual or group work and are usually accompanied by intensive work phases, e.g., to produce excerpts or summaries. These practices are characterized—unlike the mobile usage practices in the formal teaching and learning context—by activities that are rather location-bound, for which students consciously take time.

Module completion practices (Factor 3) are characterized by a high degree of standardization and a strong institutional connection. These include time-intensive activities that serve the preparation of term papers, such as the writing and formatting of texts, but also conceptual activities aimed at preparing presentations. These require a high level of concentration and regular dialogue with other students in order to overcome challenges that arise during content-related and conceptual work (

Table 5).

Taking the continuum model (

Rosemann, 2025a) into account, the practices identified through factor analysis exhibit certain variations in their positioning within the model. While mobile usage practices are primarily situated across the formal contexts, regular study- and leisure-related practices span all contexts of the model. This indicates a high degree of flexibility in these practices, with considerable variation in their adoption depending on the individual. In contrast, practices related to module completion primarily emerge in informal–digital contexts, even though they are subject to particularly strong formal requirements.

4.5. Characteristics of Challenging Situations in Dealing with Digital Media

Over the 10-day survey period of the learning and usage diary study, 21 students reported a total of 27 challenging situations that occurred when using digital media. Based on practice- and subject-oriented theories (

Section 2), challenging situations arise when experiences of discrepancies or disruptions—where a subject’s previous understanding of the world and of themselves in a specific learning context is perceived as insufficient—are recognized as opportunities for learning. In such situations, existing patterns of learning and media use are no longer sufficient, resulting in alternative learning and usage activities involving digital media (

Rosemann, 2025a).

In this context, the situational results indicate that laptops play a key role in guiding students’ social practice in dealing with challenges, whereas other (mobile) devices are not applied in these situations. Although smartphones and tablets are certainly used to fulfil study-related tasks, their use is rarely accompanied by challenging moments that require additional digital skill acquisition. This suggests routinised usage practices on the part of students that characterize the use of such devices. Students most frequently experience challenging moments during the design and creation of (innovative) digital content (N = 9). The second-most-common challenges reported by students are those that arise while solving technical problems (N = 7), yet they only rarely report such moments when exchanging information using digital technologies or analyzing data, information, and digital content. From the results of the in-depth follow-up questions on the characteristics of the situations, it can also be concluded that the students are predominantly at their private desks at the time of these challenging situations. By far the largest proportion of challenging situations occur while working with standard software such as MS Office, e.g., when digital material is created during the preparation and follow-up of seminars or for the completion of module work. More specifically, the reported difficulties are primarily of a technical–procedural nature and relate to formatting issues, such as setting up page numbering starting from a specific page (e.g., from page three). These challenges are therefore less associated with cognitive overload, organizational problems, or pedagogical demands, but rather with the practical implementation of document formatting requirements within standard software environments. Moreover, a few challenging situations arise during the acquisition of specific software for data analysis (e.g., SPSS) or video editing.

4.6. Interrelationship Between Spatial Framework Conditions and Practices

Multiple linear regression analyses were carried out in order to obtain information on the direction and effect size of the individual independent variables of the social order of practices (possession of digital media) and the identified digital media use practices. These serve to determine the explanatory value of the independent variables for the frequency of the perception of learning-relevant situations (dependent variable) in study life. The analyses were preceded by an examination of the conditions of multicollinearity and autocorrelation using the Durbin–Watson statistic (

Janssen & Laatz, 2013, p. 413). In the multiple linear regression analysis, the independent variables were gradually included in the regression model. The initial model thematizes physical access to digital media. This is gradually expanded to include the three practices of dealing with digital media. The coefficient of determination R

2 is used to determine the quality of the model, and the significance is determined using the F-test.

The variance explanation of the first model is 13.1% (

Table 6). In Model 1, marginally significant negative effects are found for laptop ownership (B = −1.988, ß = −0.508,

p < 0.1), indicating that mere possession of such a comprehensive medium does not necessarily lead to a higher frequency of perceiving learning-relevant situations. By adding the accompanying practices in the formal teaching and learning context (model 2), this increases significantly to 29.4%. Against this background, positive standardized coefficients are apparent, suggesting that intensive use of digital media in formal learning contexts (ß = 0.459,

p > 0.1) is associated with a higher frequency of perceiving learning-relevant situations. Model 3 also includes the regular study- and leisure-related practices, which increases the variance explanation by a further 9% to 38.4%. The goodness of fit of the model is significant here (

p < 0.024). Furthermore, the highly significant positive effects at this point indicate that more intensive study- and leisure-related practices dealing with digital media are associated with a higher likelihood of encountering learning-relevant situations. Furthermore, the negative effect of laptop ownership (ß = −0.488 *,

p > 0.1) suggests that merely owning a laptop tends to reduce the perception of learning-relevant situations when other usage practices are taken into account. Finally, in Model 4, the practices of module completion are integrated, which again significantly increases the variance explanation to 52.1%—with a significant goodness of fit of the model (

p < 0.006). Thus, the results of the multiple linear regression analysis indicate that the availability of digital media in the individual learning environment can increase the probability of perceiving learning-relevant situations in everyday study life that arise when using digital media. Positive effects, however, are only evident for the ownership of tablets and e-book readers, as well as mobile usage practices in formal learning contexts. In other words, these digital media and usage practices offer a wide range of opportunities that can initiate digital skills development processes for students by testing software applications. The significant negative coefficient for laptop ownership, which increases from ß = −0.448 * in Model 3 to ß = −0.649 in Model 4 (

p > 0.05), suggests a substitution effect: students who primarily rely on mobile devices for flexible, location-independent work tend to use stationary setups with a PC and second monitor less frequently.

The results indicate that mere possession of a laptop does not automatically increase the likelihood of encountering learning-relevant situations; rather, specific usage practices are necessary to have an impact. Students appear to rely either on mobile devices for flexible, location-independent work or on stationary setups for more intensive tasks In particular, intensive mobile usage phases in formal teaching and learning contexts, as well as regular study- and leisure-related practices, are positively associated with a higher frequency of learning-relevant situation perception. The results underscore the significance of digital media for learning behavior and suggest that different practices in handling digital media can influence how students experience and process learning-relevant situations.

5. Discussion

The results of the digital learning and usage diary study underscore the importance of flexibility and mobility in the digital equipment of students and provide valuable insights into the social practices that emerge in the use of digital media in everyday study life. The social (learning-)practice of students is characterized by a specific interplay of digital media, which are arranged by the subject in a certain way in their individual learning environment. The results show that students use a wide variety of digital media equipment, the possible uses of which vary in terms of time and space. Smartphones, tablets, and laptops are poignant in their high degree of spatial flexibility, meaning that they are used in both the private sphere and in formal courses. Compared to other studies (e.g.,

Janschitz et al., 2021;

Dolch et al., 2021), which have so far focused primarily on the ownership and usage of digital media, the presented diary study enables a differentiated analysis of the temporal and spatial conditions under which digital media are used and how they are embedded in the social practices of students. Except for smartphones, mobile devices like laptops and tablets are used particularly intensively by students in terms of time when study-related tasks are completed individually or notes are taken during seminar participation. Smartphones are used selectively during everyday study when short-term coordination processes with others are necessary, information and data are shared with others, or information can be researched flexibility in terms of time and space. Mobile devices function as an interface between analog and digital contexts and represent bridging practices that create multiple opportunities for the development of digital competencies. This flexibility in the use of digital media offers numerous chances to develop digital competencies in various contexts, which can help counteract the digital divide. However, without reflection, the learning process remains superficial, and the digital divide may persist or even widen if students are not supported in applying, evaluating, and adapting their digital practices across different contexts. At this point, it becomes important to differentiate between technological familiarity and technological awareness (

Sneltvedt et al., 2025). While students may display a high level of confidence and routine in using digital tools across different contexts, this does not necessarily imply a reflective or strategic understanding of their use. Without explicit opportunities to develop such awareness—i.e., to critically reflect on the purposes, implication, and transferability of their digital practices—the development of digital competence remains limited to functional use.

From an educational perspective, learning environments need to be deliberately designed to make digital practices visible, discussable, and transferable across contexts. In this framework, instructors are expected to serve as learning mentors who not only evaluate learning outcomes (e.g., term papers), typically produced through independent work, but also guide students throughout the entire learning and creation process. Implementing this approach requires the adoption of innovative assessment formats (e.g., digital learning portfolios) that foster ongoing reflective practice.

From the study-, leisure-, and media-related complexes of student activities and physical access to digital media, three different practices of digital media use in social practice could be factor-analyzed. These practices are operationalized through the allocation of temporal resources, that is, how much subjective time students spend on specific activities. With reference to the current state of research on students’ practices of using digital media, the factor analysis made it possible to identify rather broad, abstract categories of practices. In this analysis, the identified practices served primarily to examine explanatory contributions in order to determine how strongly they influence the perception of learning situations. In contrast, qualitative approaches (e.g.,

Schiefner-Rohs & Krein, 2023;

Rosemann, 2025b), which focus on more interpretative evaluation procedures, allow for finer and more detailed classification. This explains why different data collection methods yield differentiated classifications, but only the combination of both qualitative and quantitative methods allows for a comprehensive view of students’ digital learning and usage practices.

The availability of digital media, particularly the use of laptops, creates many opportunities for students to try out new functions and independently design digital materials; however, these opportunities have to be actively utilized by students, as mere possession of a laptop is not sufficient to trigger digital competence development processes and thus reduce the digital divide. Thus, the results of the multivariate regression analysis—which draws on the previously identified practices—show that flexible, reflective, and critical use of digital media within the continuum of learning contexts is particularly decisive for the perception of learning-relevant situations. These findings suggest that teaching formats which explicitly require students to reflect on their digital practices—such as comparing tools, justifying media choices, or transferring practices between study-related and non-study contexts—are more likely to be perceived as learning-relevant and supportive of digital competence development. In this context, regular study- and leisure-related practices, which include research activities and the completion of module tasks, offer a wide range of learning opportunities and highlight the importance of instructors’ roles in shaping these practices. The relevance of these findings becomes particularly apparent when compared with international studies. At this point, the study can be situated, on the one hand, within the international research context, which shows that the digital competencies and didactic expertise of instructors are crucial for fostering specific student learning practices. These practices should actively engage students, promote critical reflection, and enable collaborative learning processes (

Dong Dang et al., 2024). On the other hand, it cannot be ruled out that, in international comparison, there are cultural, societal, and infrastructural differences in students’ digital learning and usage practices. These differences are particularly evident in the temporal and spatial patterns of specific digital media use. Recent international studies indicate, for example, that students in developing countries rely primarily on smartphones as their central mobile devices, while laptops are used less frequently (

Patrick Saidi et al., 2025;

Imtinan et al., 2025). By contrast, European studies suggest that differences in digital learning and usage practices of German students compared to those of students in other European countries are less pronounced. Findings from Greece (

Nikolopoulou, 2022) and Spain (

López-Noguero & Gallardo-López, 2022) indicate that students primarily use smartphones for flexible, time- and location-independent information searching, accessing course materials, and communication. At this point, cross-country comparisons could be conducted to identify how cultural, infrastructural, and educational factors shape students’ digital practices and to determine which conditions support more effective and equitable digital learning. At the same time, these practices appear to be strongly dependent on higher education institutions, suggesting that differences may also exist within countries depending on institutional policies, available resources, and teaching approaches.

In summary, three central areas of action for higher education institutions can be identified based on the findings: Curricula should be designed to integrate structured opportunities for students to reflect on their digital practices, enabling the development of technological awareness alongside subject-specific knowledge. Further, universities need learning and support offerings that are accessible to all instructors and students in order to promote active engagement with a variety of digital applications (e.g., software, AI tools). Higher education institutions should provide low-threshold support structures, such as easily accessible guidance, workshops, and advisory services, to help teachers and students develop reflective and transferable digital competencies. Furthermore, the indirect promotion of digital competencies through structured integration of digital tools into formal learning and teaching contexts is particularly important, as it allows students to develop skills organically while engaging with their regular coursework. Moreover, the probability of perceiving learning-relevant situations increases when students carry out digital practices that begin in the context of formal teaching and learning settings at university. These include self-study tasks requiring students to design digital materials actively and autonomously (e.g., podcasts, videos). Similarly, lecturers can initiate learning-relevant situations that can initiate digital skill development processes with digital media in courses, especially in group work sessions. Mobile devices should be regarded not as a disruptive factor, but as a didactic resource that can meaningfully support and complement learning processes. Against this background, regular reflection phases during the execution of individual and group work promote a reflective, critical approach to digital media and materials. These reflection phases can contribute to generating a change in perspective on the part of the subject, thereby stimulating sensitivities in the use of digital information that accompany the learning process and thus initiate processes of digital competence development.

6. Conclusions and Limitations

This learning and usage diary study provides a deeper insight into the interplay between student’s individual (digital) learning environments and their (digital) learning and usage practices, which are shaped by the culture of digitality, to derive actionable recommendations for promoting digital competencies. The study had the advantage that memory-related issues—which frequently occur in cross-sectional surveys—were reduced due to the shorter reference period of the items. Using this method, it was possible to not only capture subjective assessments of the time spent on study-relevant activities but also to identify particularly challenging moments that students encounter when dealing with digital media. However, it cannot be ruled out that, due to memory issues, some research-relevant situations may remain unaccounted for. Even the relatively low-frequency of use of specific programs and software (e.g., SPSS, video editing tools) within formal teaching and learning contexts in higher education may explain why students have rarely encountered challenging situations when working with these applications.

Even so, memory distortions in retrospective subjective assessments of the time spent on activities cannot be ruled out (see, among others

Schmidt-Lauff, 2025), although the short reference period of the survey instrument used contributed to reducing them. Supplementing these subjective assessments of time durations with digitally generated time logs could provide interesting insights and reduce memory issues. This could be implemented, for example, through the use of time tracking software, although its incorporation into the research process involves some methodological challenges in data collection and interpretation that can only be mitigated through triangulation of different methodologies. Thus, (digital) ethnographic observations—combined with in-depth (episodic) interviews—could provide valuable insights into identifying situational variations that arise in the (learning-related) use of digital media. An alternative approach would be to combine subjective self-assessments, such as those collected in the present study, with learning analytics, allowing digital learning and usage practices to be examined from multiple perspectives and thus linking subjective and objective approaches in a meaningful way. This method could provide a deeper understanding of students’ perception of time in the context of digitalization, supporting a triangulated perspective on time perception (

Schmidt-Lauff et al., 2025).

In this regard, future studies should place greater emphasis on contextual factors of the (individual and social) learning environment (

Vallo Hult & Byström, 2022) to better understand the interplay between the orders of social practices and specific (learning) activities. In the study presented here, the focus was on the design of students’ individual (digital) learning environments and less on their social and cultural conditions. Considering these factors could provide valuable insights into how collective practices, institutional frameworks, and cultural norms influence the use of digital media and, in turn, promote or inhibit the development of digital competencies. Furthermore, for a comprehensive explanation of the “digital divide,” alongside physical access and specific practices, future studies could also consider subjective motives and specific competencies in handling digital media and their content, drawing from

J. van Dijk (

2020).

In summary, while this learning and usage diary study provides valuable insights into the practices that emerge from the interrelationship between individual digital learning environments and students’ study-, leisure-, and media-related activities, this study goes beyond mere usage and time studies and offers valuable recommendations for designing higher education environments that foster active learning practices and reflection, which can initiate and support processes of digital competency development.