Integrating Generative AI into Live Case Studies for Experiential Learning in Operations Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The Promises and Pitfalls of GenAI in Higher Education

2.2. Live Case Studies as Authentic Learning Contexts

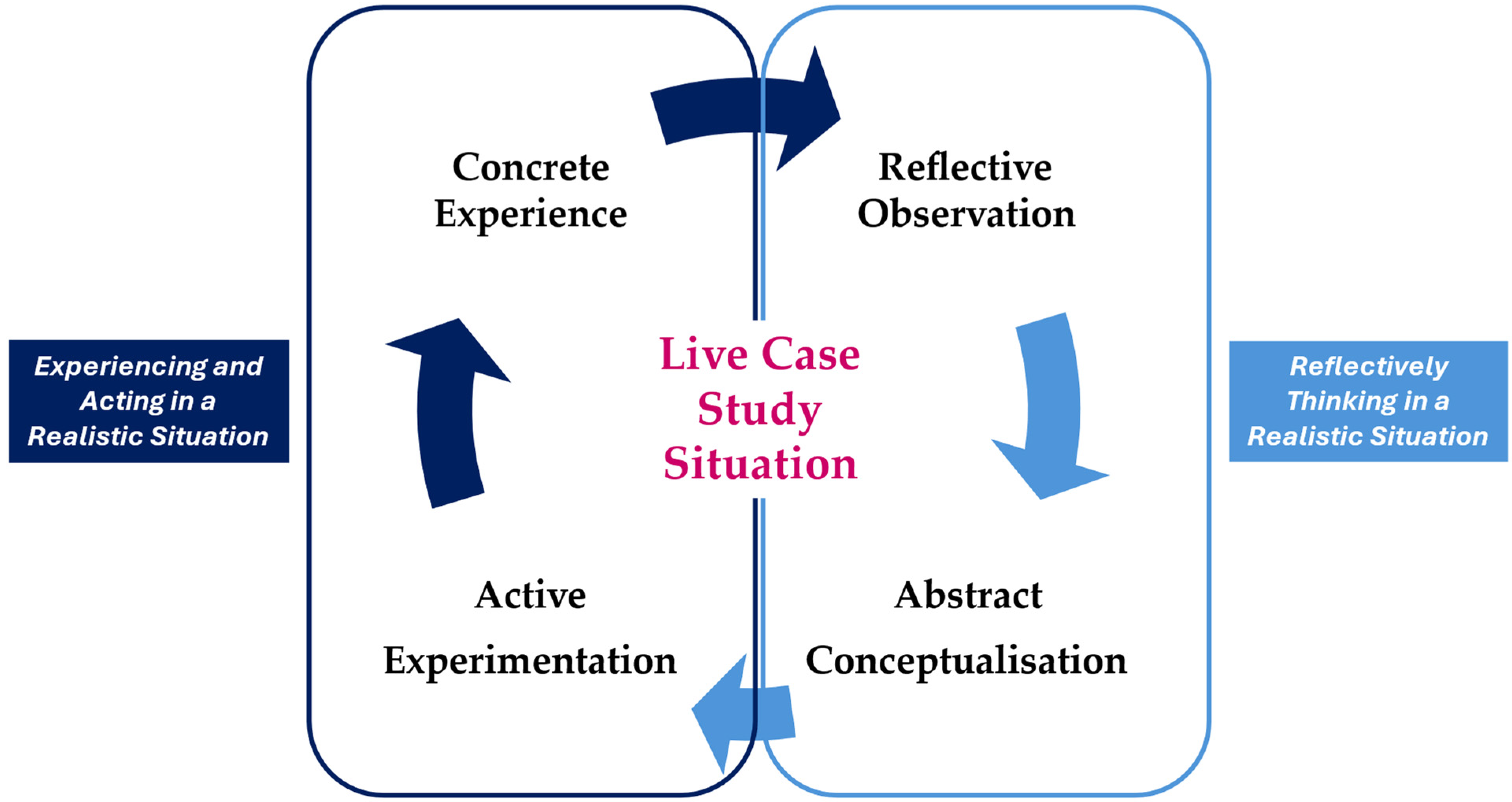

2.3. Experiential Learning and Kolb’s ELC Framework

- Active engagement requires learners to participate rather than passively receive knowledge (Bonwell & Aison, 1991).

- Iterative and cyclical progress mirrors natural human learning and reinforces adaptability (A. Kolb & Kolb, 2018).

- Context dependence is most potent when learning occurs in authentic, real-world environments (Villarroel et al., 2019).

2.4. Student Agency in GenAI-Enhanced Learning

- Concrete Experience: Students choose how to engage with stakeholders and prioritise enquiries.

- Reflective Observation: Students critically reframe their experiences, challenging dominant biases (Lipponen & Kumpulainen, 2011).

- Abstract Conceptualisation: Theories are used flexibly to reinterpret findings (Priestley et al., 2012).

- Active Experimentation: Students propose creative solutions that reflect their values, identity, and commitments (Rajala et al., 2016).

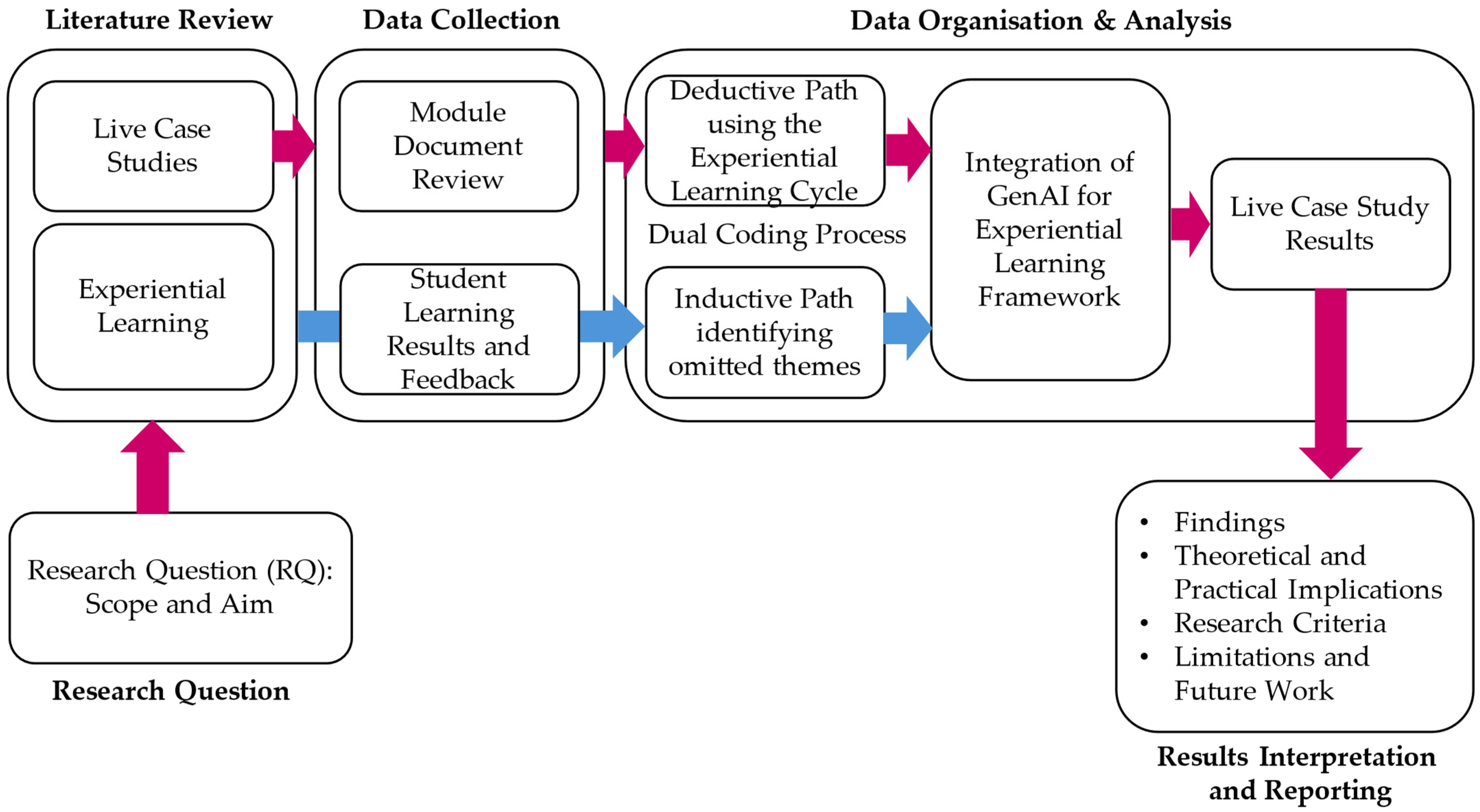

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Data Organisation and Analysis

- Guided by Kolb’s ELC, deductive codes were assigned to capture evidence for each cycle stage: CE, RO, AC, and AE (Guest et al., 2012). Additionally, assignment-related codes were included to categorise students’ proposals in the live case study. Codes regarding value proposition, creation mechanisms, network, capture strategies, and operational implications allowed the identification of servitisation enhancements to the business model and its operations. To enhance reliability, the student outputs were independently double-coded by two authors. Discrepancies were discussed to achieve consensus by (i) identifying and contrasting differences, (ii) clarifying views and interpretations, (iii) reconciling and integrating descriptions, and (iv) allocating descriptions to the corresponding code.

- Inductive coding identified emergent themes beyond the theoretical framework (Ryan & Bernard, 2003). This technique involves identifying recurring concepts, highlighting gaps (i.e., “silences”), and capturing unexpected perspectives. The two coders identified and grouped the new themes.

- Student achievements and feedback were analysed using descriptive statistics to provide an accessible overview of learning outcomes and engagement patterns, appropriate for the exploratory nature and sample size of this single case (Garay-Rondero et al., 2019).

3.3. Results Discussion and Reporting

3.4. Methodological Scope

- Transparent coding was aligned with Kolb’s ELC.

- Reliability checks via intercoder agreement on a sample of student outputs.

- Validation across multiple data sources was performed.

- Inclusion of student quotations to support the interpretation.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

4. Results

4.1. The Live Case Study Development and Design

- Explanation of the capabilities and limitations of GenAI,

- A list of prompts for effective GenAI use, and

- A GenAI-produced assignment exemplar to highlight both the possibilities and shortcomings.

- Input an initial prompt for conceptual clarification (e.g., servitisation, business models, and Indian–Bangladeshi restaurants).

- Add incremental prompts on specific topics (e.g., Indian–Bangladeshi restaurants in the UK), and gradually provide more background information.

- Use iterative refinement prompts for content generation (e.g., exploring alternative value propositions, creation mechanisms, delivery networks, and capture requirements.

- Combine outputs from incremental steps to create comprehensive, contextually rich analyses (e.g., upscaling business models and their operational implications).

- Refine outputs using feedback from literature, primary data, and staff/researcher input.

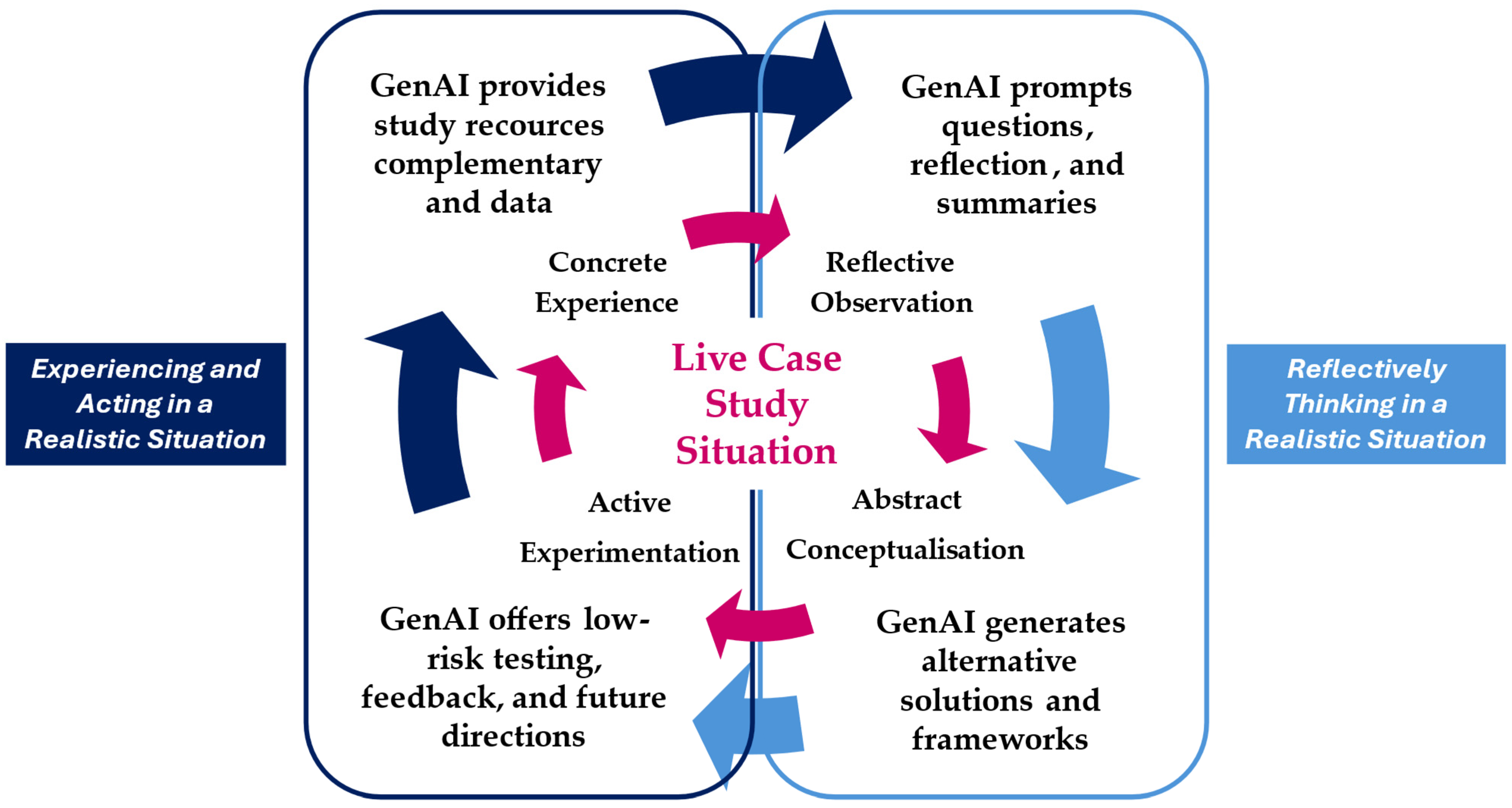

4.2. Integration of GenAI into the ELC and Student Outputs

- Concrete experience (CE): GenAI supported students by offering contextual information about the UK Bangladeshi catering sector and helping them prepare targeted questions before engaging with the restaurant. One report noted, “Using GenAI helped understand the market and prepare better questions for the restaurant visit”.

- Reflective observation (RO): Students used GenAI to structure their reflections and explore alternative interpretations of their observations. GenAI-generated probing questions prompted students to critically examine the underlying causes of operational issues. It was reported that “the AI asked questions that hadn’t been considered—it helped think about why certain problems kept recurring”.

- Abstract conceptualisation (AC): GenAI assisted students in linking their observations to servitisation and business model frameworks by generating alternative conceptual approaches. Students used these outputs to compare potential strategies before selecting and refining their proposals. One cluster of students reported that “GenAI helped brainstorm solutions and compare different business model ideas before selection”.

- Active experimentation (AE): In the AE stage, students used GenAI as a low-risk “testing space” to iterate their servitisation proposals and explore their operational implications. GenAI-generated suggestions were refined by comparing them with primary data and tutor feedback. Another cluster noted, “GenAI allowed configuring different scenarios and testing new solutions”.

4.3. Student Assessment and Reflection

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings on the Use of GenAI in the Live Case Study

- Realistic experiences (Charlebois & Foti, 2017): Students immersed themselves in a real-world scenario, interacting with staff, assessing the restaurant’s challenges and opportunities, crafting servitisation strategies, and proposing actionable solutions. Because of the dynamic and authentic business context, students adapted their thinking and actions to a real-world scenario, mirroring professional challenges.

- Live case studies enhance the learning process (Culpin & Scott, 2012): Students reported improvements in skills related to the intended learning outcomes, particularly in identifying areas for decision-making, understanding the role of operations management in performance, and recognising its strategic importance. This suggests a contribution to achieving the learning targets.

- Integration of theory and practice (Elam & Spotts, 2004; Neubert et al., 2020): By collaborating with the restaurant, students effectively connected theoretical concepts to practical applications in situational contexts. This approach enabled them to analyse, critically implement, and understand the fundamental principles of operations management and business strategy.

5.2. Findings on Differential Effectiveness of GenAI Use

5.3. Findings on GenAI and Experiential Learning

- Complemented concrete experience: GenAI helped situate some learners in a real-world problem before and during their direct interactions with the restaurant and its stakeholders, thereby reducing time and effort.

- Enhanced reflective observation: GenAI-supported reflection helped some students deepen their investigations and make deeper conceptual connections.

- Facilitated abstract conceptualisation: GenAI accelerated idea generation by offering innovative business models and operational strategies, supporting the transition from observation to conceptual solutions and frameworks.

- Support for active experimentation: GenAI serves as a low-risk environment for testing business model enhancements and obtaining feedback before formalising recommendations.

5.4. Findings on Student Performance

5.5. Theoretical and Practical Implications

- Clarify objectives: Align GenAI use with higher-order skills (reflection, critical thinking, and application).

- Develop GenAI literacy: Provide orientation on prompting strategies and critical evaluation of outputs.

- Design structured prompts: Scaffold iterative use of GenAI across Kolb’s stages (CE, RO, AC, and AE).

- Balance GenAI and judgement: Encourage students to adapt to or challenge suggestions from GenAI.

- Embed ethical use: Explicitly address bias, originality, and academic integrity within the pedagogical and instructional design.

- Integrate reflection: Require students to document how GenAI supports (or limits) their learning.

- Plan for scalability: Anticipate resource demands and adapt the approach to different class sizes and disciplines.

- Anticipate agency barriers: Scaffold agency support by offering equitable conditions and autonomy-supportive teaching.

5.6. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AC | Abstract conceptualisation |

| AE | Active experimentation |

| CE | Concrete experience |

| ELC | Experiential Learning Cycle |

| F | Cumulative frequency |

| GenAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| n | Number of respondents |

| RQ | Research Question |

| Std Dev | Standard deviation |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Example 1: Subscription-Based Culinary Experience Model

- Hands-on cooking workshops led by the restaurant’s chefs

- Virtual cooking tutorials offered through a digital platform

- Cultural storytelling events themed around Bangladeshi–Indian cuisine and traditions

Appendix A.2. Example 2: Technology-Enabled Personalisation Model

- Personalised menu recommendations based on customer preferences

- A data-driven loyalty and rewards programme

- Pre-ordering and table-planning functionalities

- A customer feedback dashboard to inform operational improvements

Appendix A.3. Example 3: Sustainability-Driven Business Model

- Partnering with local organic suppliers to increase ingredient quality and reduce food miles

- Introducing eco-friendly packaging for takeaway services

- Offering a sustainable menu tier with environmentally responsible meal options

- Promoting sustainability practices through marketing and community engagement

Appendix A.4. Cross-Cutting Elements Across Student Proposals

- Value Proposition. Students consistently aimed to enhance the customer experience by offering the following:

- Authentic and immersive dining experiences

- Personalised and technology-enhanced services

- Cultural and educational components

- Health-conscious or sustainability-oriented offerings

- Value-creation mechanisms. Proposals involved:

- Integrating digital tools for personalisation and efficiency

- Developing staff skills to deliver enhanced services

- Leveraging culinary expertise to create unique experiences

- Establishing partnerships with suppliers and cultural organisations

- Value Network. Students recommended forming alliances with:

- Technology providers

- Local organic producers

- Cultural associations

- Community influencers

These partnerships broaden operational capabilities and deepen community engagement. - Value-Capture Strategies. The revenue diversification strategies included:

- Subscription plans

- Event hosting and workshops

- Premium dining packages

- Virtual classes and branded products

- Operational Implications. Students identified several operational adjustments necessary to support the redesigned business model.

- Strengthened supply chain management and collaboration

- Use of data analytics for operations and customer insights

- Staff training for service expansion and digital adoption

- Scalable services to meet variable demand

- Integration of sustainable practices in sourcing and packaging

- Enhanced customer-centric processes

Appendix A.5. Summary

References

- Archer, M., Morley, D. A., & Souppez, J.-B. R. G. (2021). Real world learning and authentic assessment. In D. A. Morley, & M. G. Jamil (Eds.), Applied pedagogies for higher education (pp. 323–341). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahroun, Z., Anane, C., Ahmed, V., & Zacca, A. (2023). Transforming education: A comprehensive review of generative artificial intelligence in educational settings through bibliometric and content analysis. Sustainability, 15(17), 12983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A. C., Jensen, P. J., & Kolb, D. A. (2002). Conversational learning: An experiential approach to knowledge creation. Quorum Books. [Google Scholar]

- Belkina, M., Daniel, S., Nikolic, S., Haque, R., Lyden, S., Neal, P., Grundy, S., & Hassan, G. M. (2025). Implementing generative AI (GenAI) in higher education: A systematic review of case studies. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 8, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsteiner, H., Avery, G. C., & Neumann, R. (2010). Kolb’s experiential learning model: Critique from a modelling perspective. Studies in Continuing Education, 32(1), 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, C., Niven, J. E., & Hazell, C. M. (2023). Predictors of UK postgraduate researcher attendance behaviours and mental health-related attrition intention. Current Psychology, 42(34), 30521–30534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, M., Khosravi, H., De Laat, M., Bergdahl, N., Negrea, V., Oxley, E., Pham, P., Chong, S. W., & Siemens, G. (2024). A meta systematic review of artificial intelligence in higher education: A call for increased ethics, collaboration, and rigour. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonwell, C. C., & Aison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom (No. 1 ED340272). Jossey-Bass.

- Bradford, D. L. (2019). Ethical issues in experiential learning. Journal of Management Education, 43(1), 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese Barton, A., & Tan, E. (2020). Beyond equity as inclusion: A framework of “rightful presence” for guiding justice-oriented studies in teaching and learning. Educational Researcher, 49(6), 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlebois, S., & Foti, L. (2017). Using a live case study and co-opetition to explore sustainability and ethics in a classroom: Exporting fresh water to China. Global Business Review, 18(6), 1400–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J., Cowling, M., Central Queensland University Australia, Allen, K.-A., & Monash University Australia. (2023). Leadership is needed for ethical ChatGPT: Character, assessment, and learning using artificial intelligence (AI). Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 20(3), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., & Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(1), 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culpin, V., & Scott, H. (2012). The effectiveness of a live case study approach: Increasing knowledge and understanding of ‘hard’ versus ‘soft’ skills in executive education. Management Learning, 43(5), 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, K. A. (2021). Smart education framework. Smart Learning Environments, 8(1), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zeeuw, G. (1996). Three phases of science: A methodological exploration. Working Paper 7. Centre for Systems and Information Sciences, University of Lincolnshire and Humberside. [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle, P., Wojdak, K., & Walters, A. (2023). Defining active learning: A restricted systematic review. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drisko, J. W. (2025). Transferability and generalization in qualitative research. Research on Social Work Practice, 35(1), 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elam, E. L. R., & Spotts, H. E. (2004). Achieving marketing curriculum integration: A live case study approach. Journal of Marketing Education, 26(1), 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayary, A. (2024). Integrating generative AI in active learning environments: Enhancing metacognition and technological skills. Journal of Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics, 22(3), 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., & Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educational Research Review, 10, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay-Rondero, C. L., Calvo, E. Z. R., & Salinas-Navarro, D. E. (2019, October 16–19). Developing and assessing engineering competencies at experiential learning spaces. 2019 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) (pp. 1–5), Covington, KY, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K., & Namey, E. (2012). Applied thematic analysis. SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harry, A., & Sayudin, S. (2023). Role of AI in education. Interdisciplinary Journal and Humanity (INJURITY), 2(3), 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J. C., & Li, Y. (2024). Generative AI for operations management education and learning: A critical assessment and analysis. International Journal of Services and Standards, 14(4), 10072276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeister, C., & Pilz, M. (2023). Do cases always deliver what they promise? A Quality analysis of business cases in higher education. Education Sciences, 14(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, N. (2018). Engaging with assessment: Increasing student engagement through continuous assessment. Active Learning in Higher Education, 19(1), 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W., Porayska-Pomsta, K., Holstein, K., Sutherland, E., Baker, T., Shum, S. B., Santos, O. C., Rodrigo, M. T., Cukurova, M., Bittencourt, I. I., & Koedinger, K. R. (2022). Ethics of AI in education: Towards a community-wide framework. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 32(3), 504–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlin, C., Hronska, B., & Nordmann, E. (2024). I can be a “normal” student: The role of lecture capture in supporting disabled and neurodivergent students’ participation in higher education. Higher Education, 88(6), 2075–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, K. H. (2017). Authentic assessment. In Oxford research encyclopedia of education. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, A., & Kolb, D. (2018). Eight important things to know about the experiential learning cycle. Australian Educational Leader, 40, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Y. (2021). The role of experiential learning on Students’ motivation and classroom engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 771272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, G., Amzalag, M., Shaked, N., Zaguri, Y., Kohen-Vacs, D., Gal, E., Zailer, G., & Barak-Medina, E. (2024). Strategies for integrating generative AI into higher education: Navigating challenges and leveraging opportunities. Education Sciences, 14(5), 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. C., & Low, M. Y. H. (2024). Using genAI in education: The case for critical thinking. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 7, 1452131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, L. (2015). Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 4(3), 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limonova, V., Dos Santos, A. M. P., Mamede, J. H. P. S., & De Jesus Filipe, V. M. (2024). Maximising attendance in higher education: How AI and gamification strategies can boost student engagement and participation. In Á. Rocha, H. Adeli, G. Dzemyda, F. Moreira, & A. Poniszewska-Marańda (Eds.), Good practices and new perspectives in information systems and technologies (Vol. 988, pp. 64–70). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipponen, L., & Kumpulainen, K. (2011). Acting as accountable authors: Creating interactional spaces for agency work in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(5), 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maanvi, S. (2017, December 5). What’s the difference between a curry house and an indian restaurant? The Salt What’s on Your Plate. Available online: https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/12/05/567004913 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Markulis, P. M. (1985). The live case study: Filling the gap between the case study and the experiential exercise. In Developments in business simulation and experiential learning: Proceedings of the annual ABSEL conference (Vol. 12). Open Journal Systems. Available online: https://absel-ojs-ttu.tdl.org/absel/article/view/2195 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Michel-Villarreal, R., Vilalta-Perdomo, E., Salinas-Navarro, D. E., Thierry-Aguilera, R., & Gerardou, F. S. (2023). Challenges and opportunities of generative AI for higher education as explained by ChatGPT. Education Sciences, 13(9), 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubert, M., Rams, W., & Utikal, H. (2020). Experiential learning with live case studies. International Journal of Teaching and Case Studies, 11(2), 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, J., Rodwell, J., Curry, L., & Marks, G. (2019). A face in a sea of faces: Exploring university students’ reasons for non-attendance to teaching sessions. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43(4), 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, M., Edwards, R., Priestley, A., & Miller, K. (2012). Teacher agency in curriculum making: Agents of change and spaces for Manoeuvre. Curriculum Inquiry, 42(2), 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y. (2025). Pedagogical applications of generative AI in higher education: A systematic review of the field. TechTrends, 69(5), 1105–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radcliffe, D. (2009). A Pedagogy-space-technology (PST) framework for designing and evaluating learning places. In D. Radcliffe, H. Wilson, D. Powell, & B. Tibbetts (Eds.), Learning spaces in higher education: Positive outcomes by design (pp. 9–16). The University of Queensland. [Google Scholar]

- Raddats, C., Kowalkowski, C., Benedettini, O., Burton, J., & Gebauer, H. (2019). Servitization: A contemporary thematic review of four major research streams. Industrial Marketing Management, 83, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajala, A., Martin, J., & Kumpulainen, K. (2016). Agency and learning: Researching agency in educational interactions. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 10, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, K. J., & Smith, C. (2009). Live case analysis: Pedagogical problems and prospects in management education. American Journal of Business Education (AJBE), 2(9), 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Rojas, L. I., Salvador-Ullauri, L., & Acosta-Vargas, P. (2024). Collaborative working and critical thinking: Adoption of generative artificial intelligence tools in higher education. Sustainability, 16(13), 5367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, G. W., & Bernard, H. R. (2003). Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods, 15(1), 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D. E., Da Silva-Ovando, A. C., & Palma-Mendoza, J. A. (2024a). Experiential learning labs for the post-COVID-19 pandemic era. Education Sciences, 14(7), 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D. E., & Garay-Rondero, C. L. (2020, November 24–27). Experiential learning for sustainable urban mobility in industrial engineering education. 2020 IEEE International Conference on Technology Management, Operations and Decisions (ICTMOD) (pp. 1–8), Marrakech, Morocco. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D. E., Pacheco-Velazquez, E., & Da Silva-Ovando, A. C. (2024b). (Re-)shaping learning experiences in supply chain management and logistics education under disruptive uncertain situations. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1348194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D. E., & Rodríguez Calvo, E. Z. (2020). Social lab for sustainable logistics: Developing learning outcomes in engineering education. In A. Leiras, C. A. González-Calderón, I. de Brito Junior, S. Villa, & H. T. Y. Yoshizaki (Eds.), Operations management for social good (pp. 1065–1074). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D. E., Vilalta-Perdomo, E., Michel-Villarreal, R., & Montesinos, L. (2024c). Designing experiential learning activities with generative artificial intelligence tools for authentic assessment. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 21(4), 708–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Navarro, D. E., Vilalta-Perdomo, E., Michel-Villarreal, R., & Montesinos, L. (2024d). Using generative artificial intelligence tools to explain and enhance experiential learning for authentic assessment. Education Sciences, 14(1), 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M. F., Yahaya, L. A., Adedokun-Shittu, N. A., Bello, M. B., Ogunjimi, M. O., -Steve, F. B., Atolagbe, A. A., Abdullahi, M. S., Alabi, H. I., Dominic, O. L., & Olaitan, O. L. (2025). Enhancing academic engagement through an interactive digital manual: A study on general studies students at the University of Ilorin. Pengabdian: Jurnal Abdimas, 3(1), 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonell, S., & Macklin, R. (2019). Work integrated learning initiatives: Live case studies as a mainstream WIL assessment. Studies in Higher Education, 44(7), 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schryen, G., Marrone, M., & Yang, J. (2025). Exploring the scope of generative AI in literature review development. Electronic Markets, 35(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N. (2019). Should robots replace teachers? AI and the future of education. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, R., & Deng, X. (2025). Using generative AI to enhance experiential learning: An exploratory study of ChatGPT Use by university students. Journal of Information Systems Education, 36(1), 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shailendra, S., Kadel, R., & Sharma, A. (2024). Framework for adoption of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) in education. IEEE Transactions on Education, 67(5), 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoikova, E., Nikolov, R., & Kovatcheva, E. (2017). Conceptualising of smart education. Electrotechnica & Electronica (E+ E), 52(3–4), 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Symeou, L., Louca, L., Kavadella, A., Mackay, J., Danidou, Y., & Raffay, V. (2025). Development of evidence-based guidelines for the integration of generative AI in university education through a multidisciplinary, consensus-based approach. European Journal of Dental Education, 29(2), 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharenou, P., Donohue, R., & Cooper, B. (2007a). Case study research designs. In Management research methods (pp. 72–87). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharenou, P., Donohue, R., & Cooper, B. (2007b). The research process. In Management research methods (pp. 3–30). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillmanns, T., Salomão Filho, A., Rudra, S., Weber, P., Dawitz, J., Wiersma, E., Dudenaite, D., & Reynolds, S. (2025). Mapping tomorrow’s teaching and learning spaces: A systematic review on GenAI in higher education. Trends in Higher Education, 4(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timans, R., Wouters, P., & Heilbron, J. (2019). Mixed methods research: What it is and what it could be. Theory and Society, 48(2), 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahl, M. (1997). Doing research in the social domain. In F. A. Stowell, R. L. Ison, R. Armson, J. Holloway, S. Jackson, & S. McRobb (Eds.), Systems for sustainability (pp. 147–152). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, F. J. (1999). Ethical know-how: Action, wisdom, and cognition. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Veletsianos, G., & Russell, G. S. (2014). Pedagogical Agents. In J. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. Elen, & M. J. Bishop (Eds.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 759–769). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarroel, V., Boud, D., Bloxham, S., Bruna, D., & Bruna, C. (2019). Using principles of authentic assessment to redesign written examinations and tests. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 57(1), 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vítečková, K., Cramer, T., Pilz, M., Tögel, J., Albers, S., Van Den Oord, S., & Rachwał, T. (2025). Case studies in business education: An investigation of a learner-friendly approach. Journal of International Education in Business, 18(2), 149–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., Jing, Y., & Shen, S. (2025). A systematic literature review on the application of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) in teaching within higher education: Instructional contexts, process, and strategies. The Internet and Higher Education, 65, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, G. (1990). The case for authentic assessment. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 2(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q., Weng, X., Ouyang, F., Lin, T. J., & Chiu, T. K. F. (2024). A scoping review on how generative artificial intelligence transforms assessment in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L., Greiff, S., Teuber, Z., & Gašević, D. (2024). Promises and challenges of generative artificial intelligence for human learning (Version 3). arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf, A., Pervin, N., & Román-González, M. (2024). Generative AI and the future of higher education: A threat to academic integrity or reformation? Evidence from multicultural perspectives. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Key Characteristics | Contribution to Learning | Role of GenAI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Live Case Studies | Real-time, evolving, authentic problems; interaction with external stakeholders; and situated in real-world contexts. | Authentic assessment, decision-making under uncertainty, teamwork, and applied knowledge were fostered. | They provide background information, suggest resources, generate scenario variations, and scaffold problem framing. |

| Experiential Learning | The four stages are: CE, RO, AC, and AE. | Higher-order thinking, critical reflection, transferable skills, and contextualised knowledge were developed. | Scaffold each stage: CE (contextual data), RO (probing questions), AC (alternative frameworks), AE (safe testing environment) |

| Learner Agency | Capacity to decide, critically question, co-construct, and transform one’s own learning, shaped by sociocultural and intersectional factors. | Enhancing autonomy, empowerment, creativity, and critical engagement in real-world contexts. | Acts as a catalyst: GenAI expands possibilities, but students exercise their agency by adapting, critiquing, filtering, or reorienting GenAI outputs. |

| Views on the Module | Respondents (n) | Mean | Mode | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The module is interesting | 46 | 4.3 | 4 | 0.7 |

| I am clear what the learning outcomes are for the module | 46 | 4.2 | 4 | 0.6 |

| I feel I can achieve the module learning outcomes | 46 | 4.1 | 4 | 0.6 |

| The mode of delivery works well for the module content | 46 | 3.9 | 4 | 0.7 |

| I have received sufficient academic support when I asked for it | 43 | 3.9 | 4 | 0.6 |

| I know how to get academic support if I need it | 46 | 4.2 | 4 | 0.6 |

| I have engaged well with this module | 46 | 4.1 | 4 | 0.7 |

| Questions | Mode | n-Mode | Cumulative F (3–5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| How INTERESTING was carrying out your Live Case Study learning activities? | 3 | 7 | 14 (88%) |

| How MOTIVATING was carrying out your Live Case Study learning activities? | 3 | 6 | 13 (81%) |

| How RELEVANT was the Live Case Study to develop skills for your studies and professional practice? | 3, 4 | 6 | 15 (94%) |

| How helpful were the GenAI tools in supporting the Live Case Study activities? | 3 | 5 | 11 (69%) |

| Improvement in the ability to critically identify key decision-making areas in operations management and apply them to different contexts 1. | 4 | 8 | 14 (88%) |

| Improvement in the ability to critically examine the contribution of operations management to organisational performance 1. | 4 | 7 | 12 (75%) |

| Improvement in the ability to critically discuss the strategic importance of operations management 1. | 4 | 7 | 12 (75%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E.; Palma-Mendoza, J.A.; Carlos-Arroyo, M. Integrating Generative AI into Live Case Studies for Experiential Learning in Operations Management. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010015

Salinas-Navarro DE, Vilalta-Perdomo E, Palma-Mendoza JA, Carlos-Arroyo M. Integrating Generative AI into Live Case Studies for Experiential Learning in Operations Management. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalinas-Navarro, David Ernesto, Eliseo Vilalta-Perdomo, Jaime Alberto Palma-Mendoza, and Martina Carlos-Arroyo. 2026. "Integrating Generative AI into Live Case Studies for Experiential Learning in Operations Management" Education Sciences 16, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010015

APA StyleSalinas-Navarro, D. E., Vilalta-Perdomo, E., Palma-Mendoza, J. A., & Carlos-Arroyo, M. (2026). Integrating Generative AI into Live Case Studies for Experiential Learning in Operations Management. Education Sciences, 16(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010015