How School Leaders Retain Experienced and Capable Teacher Mentors

Abstract

1. Purpose

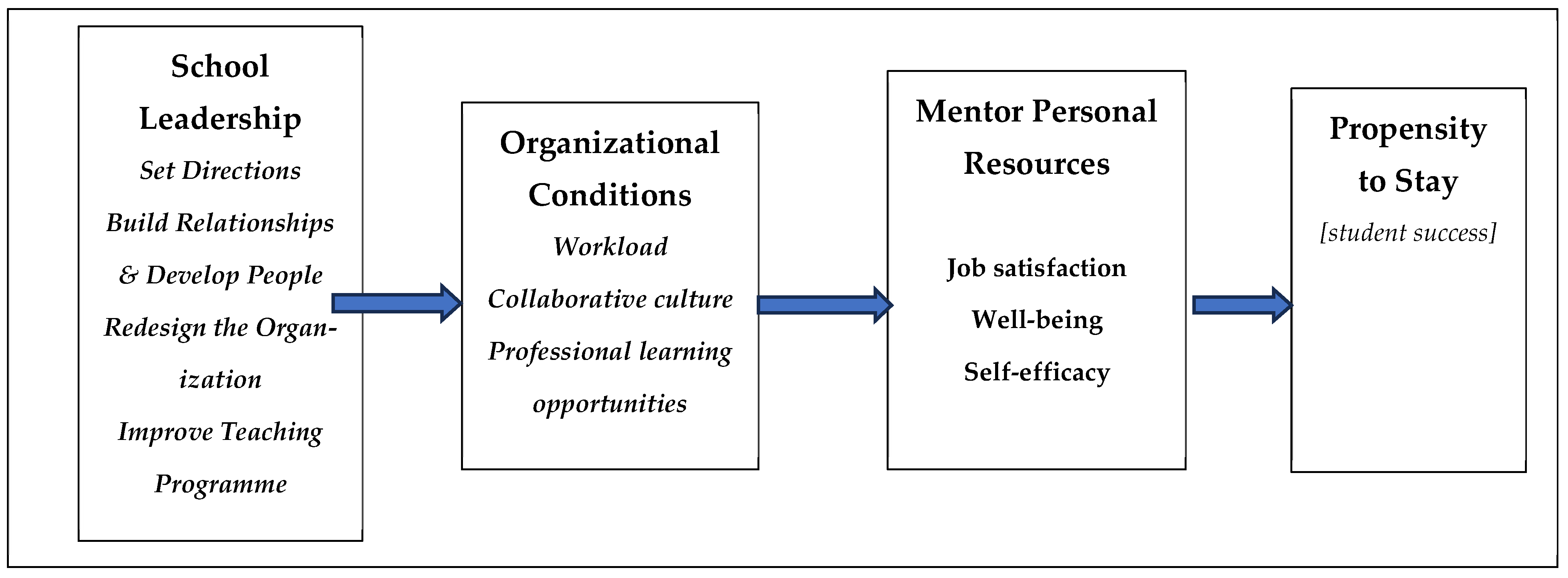

- To what extent do a selected set of TMs’ personal resources (self-efficacy, job satisfaction, well-being) influence their retention decisions?

- Which organizational conditions are strongly and positively associated with those TMs’ personal resources?

- Which leadership practices are strongly and positively associated with those key organizational conditions?

2. Context

3. Framework

3.1. School Leadership

3.2. Organizational Conditions

3.3. Personal Resources as Response to Organizational Conditions

3.4. Propensity to Stay or Leave

4. Methods

4.1. Design

4.2. Sample

4.3. Instrument

4.4. Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Data Analysis

5.2. Structural Equation Model

- Mentoring-related factors (i.e., learning and engagement with the ECF mentoring programme, in-school support and development for ECF mentors);

- School-related factors (i.e., leadership practices, professional growth opportunities, collaborative culture, mentors’ workload conditions);

- Personal resources (i.e., mentor self-efficacy, job satisfaction in teaching, job satisfaction in school, well-being in teaching, and well-being in school).

6. Discussion

- Research Question 1: Influence of Personal Resources (Self-Efficacy, Job Satisfaction, Well-Being) on TMs’ Retention Decisions

- Research Question 2: Organizational Conditions Which Influence TMs’ Personal Resources

- Research Question 3: Leadership Practices Positively Associated with Key Organizational Conditions

7. Conclusions

7.1. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

7.2. Implications for Practising School Leaders

7.3. Aim the School in Meaningful Directions

7.4. Structure the School to Encourage Engagement of All Stakeholders

7.5. Shape the Engagement of All Stakeholders to Foster the Development of the School’s Collective Intelligence

7.6. Distribute Leadership for Pedagogical Coaching

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “Integrated” signifies a combination of practices included in both transformational and instructional models of leadership (Leithwood, 2023a). |

References

- Admiraal, W., & Kittelsen Røberg, K.-I. (2023). Teachers’ job demands, resources and their job satisfaction: Satisfaction with school, career choice and teaching profession of teachers in different career stages. Teaching and Teacher Education, 125, 104063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong, B., Obuobi-Donkor, G., Burback, L., & Wei, Y. (2022). Stress, burnout, anxiety and depression among teachers: A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloe, A. M., Amo, L. C., & Shanahan, M. E. (2014). Classroom management self-efficacy and burnout: A multivariate meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 26(1), 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arens, A. K., & Morin, A. J. S. (2016). Relations between teachers’ emotional exhaustion and students’ educational outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(6), 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnsby, E. S., Aspfors, J., & Jacobsson, K. (2025). Teachers’ professional learning through mentor education: A longitudinal mixed-methods study. Education Inquiry, 16(4), 572–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, L., & Bradley, S. (2023). Teacher retention in challenging schools: Please don’t say goodbye! Teachers and Teaching, 29(7–8), 753–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control (pp. ix, 604). W H Freeman/Times Books/Henry Holt & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Bellibaş, M. Ş., Kılınç, A. Ç., & Polatcan, M. (2021). The moderation role of transformational leadership in the effect of instructional leadership on teacher professional learning and instructional practice: An integrated leadership perspective. Educational Administration Quarterly, 57(5), 776–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G., Allan, J., & Edwards, R. (2011). The theory question in research capacity building in education: Towards an agenda for research and practice. British Journal of Educational Studies, 59(3), 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billingsley, B., & Bettini, E. (2019). Special education teacher attrition and retention: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 89(5), 697–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, G. D., & Dowling, N. M. (2008). Teacher attrition and retention: A meta-analytic and narrative review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 78(3), 367–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, G., & Lance, A. (2005). Secondary teacher workload and job satisfaction: Do successful strategies for change exist? Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 33(4), 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). The trouble with teacher turnover: How teacher attrition affects students and schools. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27(36), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalofsky, N., & Krishna, V. (2009). Meaningfulness, commitment, and engagement: The intersection of a deeper level of intrinsic motivation. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 11(2), 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., & Åstebro, T. (2003). How to deal with missing categorical data: Test of a simple Bayesian method. Organizational Research Methods, 6(3), 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, R., Aloisi, C., Higgins, S., & Major, L. E. (2014). What makes great teaching? Review of the underpinning research. The Sutton Trust. Available online: https://www.suttontrust.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/What-Makes-Great-Teaching-REPORT.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Day, C., & Gu, Q. (2010). The new lives of teachers. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C., Gu, Q., & Sammons, P. (2016). The impact of leadership on student outcomes: How successful school leaders use transformational and instructional strategies to make a difference. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(2), 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C., Gu, Q., & Ylimaki, R. (2024). Educational research and the quality of successful school leadership. UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000391537 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Day, C., & Gurr, D. (Eds.). (2024). How successful schools are more than effective: Principals who build and sustain teacher and student wellbeing and achievement. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C., Sammons, P., Leithwood, K., Harris, A., Hopkins, D., Gu, Q., Brown, E., & Ahtaridou, E. (2011). Successful school leadership: Linking with learning and achievement. Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C., Sammons, P., Stobart, G., Kington, A., & Gu, Q. (2007). Teachers matter: Connecting lives, work and effectiveness. Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DeMatthews, D. E., Knight, D. S., & Shin, J. (2022). The principal-teacher churn: Understanding the relationship between leadership turnover and teacher attrition. Educational Administration Quarterly, 58(1), 76–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Brok, P., Wubbels, T., & van Tartwijk, J. (2017). Exploring beginning teachers’ attrition in The Netherlands. Teachers and Teaching, 23(8), 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Education. (2022). Get information about schools. Available online: https://www.get-information-schools.service.gov.uk/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Department for Education. (2023). Working lives of teachers and leaders—Wave 1. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1148571/Working_lives_of_teachers_and_leaders_-_wave_1_-_core_report.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Dettori, J. R., Norvell, D. C., & Chapman, J. R. (2018). The sin of missing data: Is all forgiven by way of imputation? Global Spine Journal, 8(8), 892–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, S., Steiner, E. D., & Woo, A. (2023). State of the American teacher survey: 2023 technical documentation and survey results. RAND Corporation. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1108-7.html (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Donohoo, J., O’Leary, T., & Hattie, J. (2020). The design and validation of the enabling conditions for collective teacher efficacy scale (EC-CTES). Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 5(2), 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriadou, S., Gu, Q., & Shao, X. (2025). Developing and retaining talented mentors as the signature pedagogy for school leaders. London Review of Education, 23(1), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, Y., Shirom, A., Gilboa, S., & Cooper, C. L. (2008). The mediating effects of job satisfaction and propensity to leave on role stress-job performance relationships: Combining meta-analysis and structural equation modeling. International Journal of Stress Management, 15(4), 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for windows step by step: A simple guide and reference, 11.0 update. Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Goldring, E., Grissom, J. A., Rubin, M., Neumerski, C. M., Cannata, M., Drake, T., & Schuermann, P. (2015). Make room value added: Principals’ human capital decisions and the emergence of teacher observation data. Educational Researcher, 44(2), 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A. M. (2012). Leading with meaning: Beneficiary contact, prosocial impact, and the performance effects of transformational leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55(2), 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, J. (2004). Relation of principal transformational leadership to school staff job satisfaction, staff turnover, and school performance. Journal of Educational Administration, 42(3), 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J. A., & Bartanen, B. (2019). Strategic retention: Principal effectiveness and teacher turnover in multiple-measure teacher evaluation systems. American Educational Research Journal, 56(2), 514–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J. A., & Loeb, S. (2017). Assessing principals’ assessments: Subjective evaluations of teacher effectiveness in low- and high-stakes environments. Education Finance and Policy, 12(3), 369–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J. A., Loeb, S., & Doss, C. (2016). The multiple dimensions of teacher quality: Does value-added capture teachers’ nonachievement contributions to their schools? In J. A. Grissom, & P. Youngs (Eds.), Improving teacher evaluation systems: Making the most of multiple measures (pp. 37–50). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Q., Eleftheriadou, S., & Baines, L. (2023). The impact of the Early Career Framework (ECF) programme on the work engagement, wellbeing and retention of teachers: A longitudinal study, 2021–2026. In Interim research report 2: Early career teachers’ and mentors’ reported experiences with the ECF programme. UCL Centre for Educational Leadership. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10177976/1/ECF%20Research%20Report%20%232_Full%20Report.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Gu, Q., Seymour, K., Shao, X., Eleftheriadou, S., & Leithwood, K. (2025). Workload, wellbeing, and retention: Do NPQs make a difference? UCL Centre for Educational Leadership. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10208478/1/Do%20NPQs%20Make%20a%20Difference_Final%20Report.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Hobson, A. J., Ashby, P., Malderez, A., & Tomlinson, P. D. (2009). Mentoring beginning teachers: What we know and what we don’t. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(1), 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, L., Elvira, Q., & Yates, A. (2023). What can teacher educators learn from career-change teachers’ perceptions and experiences: A systematic literature review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 132, 104208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, G. D. (2012). Teacher retention: Teacher characteristics, school characteristics, organizational characteristics, and teacher efficacy. The Journal of Educational Research, 105(4), 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. (2023). SPSS version 28. IBM. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, R. M. (2001). Teacher turnover and teacher shortages: An organizational analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 38(3), 499–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JISC. (2022). JISC online surveys. JISC. Available online: https://www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/ (accessed on 14 April 2023).

- Johnson, S. M., Kraft, M. A., & Papay, J. P. (2012). How context matters in high-need schools: The effects of teachers’ working conditions on their professional satisfaction and their students’ achievement. Teachers College Record, 114(10), 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardos, S. M., & Johnson, S. M. (2007). On their own and presumed expert: New teachers’ experience with their colleagues. Teachers College Record, 109(9), 2083–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasalak, G., & Dağyar, M. (2020). The relationship between teacher self-efficacy and teacher job satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the teaching and learning international survey (TALIS). Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 20(3), 16–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi, E., Resnick, A. F., & Gibbons, L. (2022). Principal leadership for school-wide transformation of elementary mathematics teaching: Why the principal’s conception of teacher learning matters. American Educational Research Journal, 59(6), 1051–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kraft, M. A., Marinell, W. H., & Yee, D. S.-W. (2016). School organizational contexts, teacher turnover, and student achievement: Evidence from panel data. American Educational Research Journal, 53(5), 1411–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K. (2012). The Ontario Leadership Framework with a discussion of research foundations. Institute for Educational Leadership/Ontario Ministry of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K. (2019). Characteristics of effective leadership networks: A replication and extension. School Leadership & Management, 39(2), 175–197. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K. (2023a). Integrated educational leadership. In R. Tierney, F. Rizvi, K. Ericikan, & G. Smith (Eds.), Encyclopedia of education (4th ed., Vol. 15, pp. 305–328). Elsevier Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K. (2023b). The personal resources of successful leaders: A narrative review. Education Sciences, 13(9), 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Gu, Q., Eleftheriadou, S., & Baines, L. (2024). Developing and retaining talented mentors. Interim Research Report 3. UCL Centre for Educational Leadership. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10188153/1/ECF%20Mentor%20Research%20Report_2024_Final.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2006). Transformational school leadership for large-scale reform: Effects on students, teachers, and their classroom practices. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(2), 201–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., & Louis, K. S. (2012). Linking leadership to learning. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K., Sun, J., & Schumacker, R. (2019). How school leadership influences student learning: A test of “the four paths model”. Educational Administration Quarterly, 56(4), 570–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, J. (1990). The mentor phenomenon and the social organization of teaching. Review of Research in Education, 16, 297–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Keeley, J. W., & Sui, Y. (2023). Multi-level analysis of factors influencing teacher job satisfaction in China: Evidence from the TALIS 2018. Educational Studies, 49(2), 239–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2013). Goal setting theory: The current state. In E. A. Locke, & G. P. Latham (Eds.), New developments in goal setting and task performance (pp. 623–630). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, J., & Oliveira, C. (2020). Teacher and school determinants of teacher job satisfaction: A multilevel analysis. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 31(4), 641–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Towards an understanding of teacher attrition: A meta-analysis of burnout, job satisfaction, and teachers’ intentions to quit. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. E., & Naeem, B. (2013). Towards understanding controversy on Herzberg theory of motivation. World Applied Sciences Journal, 24(8), 1031–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Master, B. (2014). Staffing for success: Linking teacher evaluation and school personnel management in practice. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInerney, D. M., Korpershoek, H., Wang, H., & Morin, A. J. S. (2018). Teachers’ occupational attributes and their psychological wellbeing, job satisfaction, occupational self-concept and quitting intentions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 71, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraal, E., Suhre, C., & van Veen, K. (2024). The importance of an explicit, shared school vision for teacher commitment. Teaching and Teacher Education, 137, 104387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshagen, M., & Erdfelder, E. (2016). A New Strategy for Testing Structural Equation Models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 23(1), 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. D., Pham, L. D., Crouch, M., & Springer, M. G. (2020). The correlates of teacher turnover: An updated and expanded Meta-analysis of the literature. Educational Research Review, 31, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwoko, J. C., Emeto, T. I., Malau-Aduli, A. E. O., & Malau-Aduli, B. S. (2023). A systematic review of the factors that influence teachers’ occupational wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(12), 6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. (2020). TALIS 2018 results (volume II): Teachers and school leaders as valued professionals, talis. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2025). Results from TALIS 2024: The state of teaching, talis. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma-Vasquez, C., Carrasco, D., & Tapia-Ladino, M. (2022). Teacher mobility: What is it, how is it measured and what factors determine it? A scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pentland, A. (2015). Social physics: How social networks can make us smarter (Illustrated ed.). Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P., Podsakoff, N., Williams, L., Huang, C., & Yang, J. (2024). Common method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quebec Fuentes, S., & Jimerson, J. B. (2020). Role enactment and types of feedback: The influence of leadership content knowledge on instructional leadership efforts. Journal of Educational Supervision, 3(2), 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronfeldt, M., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 4–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. (2020). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R. RStudio, PBC. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 9 August 2023).

- Rubin, D. B. (1976). Inference and missing data. Biometrika, 63(3), 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartain, L., Stoelinga, S. R., & Brown, E. R. (2011). Rethinking teacher evaluation in Chicago: Lessons learned from classroom observations, principal-teacher conferences, and district implementation. Consortium on Chicago School Research. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7(2), 147–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, B. H., Morris, R., Gorard, S., Kokotsaki, D., & Abdi, S. (2020). Teacher recruitment and retention: A critical review of international evidence of most promising interventions. Education Sciences, 10(10), 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergiovanni, T. (1967). Factors which affect satisfaction and dissatisfaction of teachers. Journal of Educational Administration, 5(1), 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibieta, L. (2020). Teacher shortages in England: Analysis and pay options. Education Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Silvia, C., & McGuire, M. (2010). Leading public sector networks: An empirical examination of integrative leadership behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(2), 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipahioglu, M., Mifsud, D., & Eryilmaz, N. (2025). An examination of school leadership types and their effect on teacher turnover intentions: Evidence from TALIS. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smet, M. (2022). Professional development and teacher job satisfaction: Evidence from a multilevel model. Mathematics, 10(1), 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J., Healey, K., & Min Kim, C. (2010). Formal and informal aspects of the elementary school organization. In A. J. Daly (Ed.), Social network theory and educational change (pp. 128–159). Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, M. K., & Nelson, B. S. (2003). Leadership content knowledge. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 25(4), 423–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J. A. C., White, I. R., Carlin, J. B., Spratt, M., Royston, P., Kenward, M. G., Wood, A. M., & Carpenter, J. R. (2009). Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. BMJ, 338, b2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stogdill, R. M. (1948). Personal factors associated with leadership. Journal of Psychology, 25, 35–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struyven, K., & Vanthournout, G. (2014). Teachers’ exit decisions: An investigation into the reasons why newly qualified teachers fail to enter the teaching profession or why those who do enter do not continue teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 43, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., & Leithwood, K. (2015). Direction-setting school leadership practices: A meta-analytic review of evidence about their influence. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 26(4), 499–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Zhang, R., & Forsyth, P. B. (2023). The effects of teacher trust on student learning and the malleability of teacher trust to school leadership: A 35-year meta-analysis. Educational Administration Quarterly, 59(4), 744–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the U.S. Learning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Toropova, A., Myrberg, E., & Johansson, S. (2021). Teacher job satisfaction: The importance of school working conditions and teacher characteristics. Educational Review, 73(1), 71–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unda, M. D. C. (2025). The systematic exclusion of Latinx teachers in U.S. public schools: A literature review. Race Ethnicity and Education, 28(6), 941–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2024). Global report on teachers: Addressing teacher shortages and transforming the profession. UNESCO. Available online: https://teachertaskforce.org/knowledge-hub/global-report-teachers-addressing-teacher-shortages-and-transforming-profession (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Xia, Y., & Yang, Y. (2019). RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behavior Research Methods, 51(1), 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakariya, Y. F. (2020). Investigating some construct validity threats to TALIS 2018 teacher job satisfaction scale: Implications for social science researchers and practitioners. Social Sciences, 9(4), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 981–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mentors | National Mentors (Department for Education, 2022) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 630 (78%) female | 18,574 (75%) female |

| Ethnicity | 693 (85%) white | 20,281 (86%) white |

| Age Range | 23–65 | |

| Mean (SD) | 39.9 (9.23) | |

| 21–29 | 116 (14%) | 4464 (18%) |

| 30–39 | 312 (39%) | 10,175 (41%) |

| 40–49 | 222 (28%) | 6732 (27%) |

| 50–59 | 140 (17%) | 2987 (12%) |

| 60–69 | 17 (2%) | 253 (1%) |

| Secondary school | 407 (50%) | 13,069 (52%) |

| Middle school | 1 (<1%) | |

| Primary school | 345 (43%) | 10,755 (43%) |

| Other | 57 (7%) | 1071 (4%) |

| Full-time permanent contract | 672 (83%) | All full-time, 20,165 (81%) |

| Full-time fixed term/temporary contract | 5 (<1%) | |

| Part-time permanent contract | 127 (16%) | All part-time, 3668 (15%) |

| Part-time fixed term/temporary contract | 6 (<1%) |

| Factor | Item | Unstandardised Factor Loading (SE) | Standardised Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning and engagement with ECF mentoring programme | (1) To what extent have you engaged with mentor training on the ECF programme? | 1 | 0.440 |

| (2) To what extent has your learning from the mentoring programme contributed to your confidence as a mentor to establish a constructive mentoring relationship? | 2.712 (0.242) | 0.901 | |

| (3) To what extent has your learning from the mentoring programme contributed to your confidence as a mentor to support and challenge your ECT(s)? | 2.588 (0.229) | 0.952 | |

| (4) To what extent has your learning from the mentoring programme contributed to your confidence as a mentor to provide effective developmental teaching observations and feedback? | 2.438 (0.221) | 0.866 | |

| In-school support and development for ECF mentors | (1) I have adequate time to carry out my role as a mentor. | 1 | 0.877 |

| (2) I have adequate support from my school as a mentor. | 0.682 (0.035) | 0.710 | |

| (3) The amount of time allocated to mentor-mentee sessions on ECF is appropriate to support my ECT(s). | 0.947 (0.040) | 0.811 | |

| (4) Being a mentor has contributed to my own professional development. | 0.382 (0.046) | 0.448 | |

| Successful leadership practices (a) Setting directions | Think about the person (or people) who provide(s) THE MOST SENIOR leadership in your school (e.g., Headteacher). To what extent do you agree that they do the following regarding setting direction? | ||

| (1) Gives staff a sense of overall purpose. | 1 | 0.908 | |

| (2) Demonstrates high expectations for staff’s work with learners. | 0.858 (0.033) | 0.881 | |

| (3) Demonstrates high expectations for learner behaviour. | 0.885 (0.042) | 0.846 | |

| (4) Demonstrates high expectations for learners’ academic achievement. | 0.750 (0.046) | 0.84 | |

| (5) Demonstrates high expectations for learners’ development of good health and well-being. | 0.870 (0.036) | 0.867 | |

| Successful leadership practices (b) Developing teachers | Think about the person (or people) who provide(s) THE MOST SENIOR leadership in your school (e.g., Headteacher). To what extent do you agree that they do the following regarding developing teachers? | ||

| (1) Gives us individual support to help us improve teaching practices. | 1 | 0.876 | |

| (2) Encourages us to consider new ideas for teaching. | 0.840 (0.036) | 0.854 | |

| (3) Promotes leadership development among teachers. | 0.942 (0.037) | 0.86 | |

| (4) Promotes a range of continuing professional development experiences among all staff. | 0.945 (0.038) | 0.865 | |

| (5) Encourages us to think of learning beyond the academic curriculum (e.g., persona, emotional and social education, citizenship, etc.). | 0.917 (0.039) | 0.847 | |

| Successful leadership practices (c) Redesigning the organisation | Think about the person (or people) who provide(s) THE MOST SENIOR leadership in your school (e.g., Headteacher). To what extent do you agree that they do the following regarding redesigning the organisation? | ||

| (1) Encourages collaborative work among staff. | 1 | 0.817 | |

| (2) Engages parents/carers in the school’s improvement efforts. | 1.012 (0.056) | 0.774 | |

| (3) Builds community support for the school’s improvement efforts. | 1.127 (0.055) | 0.843 | |

| (4) Allocates resources strategically based on learners’ needs. | 1.179 (0.055) | 0.879 | |

| (5) Works in collaboration with other schools. | 0.999 (0.057) | 0.755 | |

| Successful leadership practices (d) Improving the teaching programme | Think about the person (or people) who provide(s) THE MOST SENIOR leadership in your school (e.g., Headteacher). To what extent do you agree that they do the following regarding managing the teaching programme? | ||

| (1) Provides or locates resources to help us improve teaching. | 1 | 0.886 | |

| (2) Regularly observes classroom activities. | 0.938 (0.040) | 0.772 | |

| (3) After observing classroom activities, works with teachers to improve teaching. | 1.141 (0.035) | 0.882 | |

| (4) Uses coaching and mentoring to improve quality of teaching. | 1.098 (0.034) | 0.866 | |

| (5) Encourages all staff to use learners’ progress data in planning for individual learners’ needs. | 0.772 (0.038) | 0.812 | |

| Professional growth opportunities | (1) I have many opportunities to take on new challenges. | 1 | 0.793 |

| (2) I have adequate opportunities to develop my classroom teaching skills. | 1.017 (0.042) | 0.859 | |

| (3) I have adequate opportunities for learning and development as a professional. | 1.077 (0.044) | 0.88 | |

| (4) Opportunities for promotion within my school are adequately available to me. | 1.253 (0.059) | 0.726 | |

| (5) Expectations of my performance are realistic given my role and experience. | 0.855 (0.056) | 0.69 | |

| (6) Training and development rarely conflicts with my work schedule. | 0.848 (0.059) | 0.558 | |

| Collaborative culture | (1) Teachers in our school mostly work together to improve their practice. | 1 | 0.809 |

| (2) I have good relationships with my colleagues. | 0.256 (0.029) | 0.428 | |

| (3) My school has a culture of shared responsibility for school issues. | 1.095 (0.054) | 0.871 | |

| (4) There is a collaborative school culture which is characterised by mutual support. | 1.126 (0.058) | 0.907 | |

| Mentors’ workload conditions | (1) I have sufficient access to appropriate teaching and learning materials and resources. | 1 | 0.562 |

| (2) I am protected from administrative duties that interfere with my teaching. | 2.069 (0.152) | 0.823 | |

| (3) I have adequate time for lesson planning and using assessment to improve learning. | 2.227 (0.163) | 0.909 | |

| (4) I have adequate time to balance pastoral duties (i.e., care for pupils’ physical and emotional welfare) with teaching. | 2.191 (0.158) | 0.913 | |

| Self-efficacy as a mentor | (1) Overall I have been able to meet the individual needs of my early career teacher(s) (ECTs) as a mentor. | 1 | 0.614 |

| (2) I have been able to establish a strong mentor-mentee relationship. | 0.617 (0.065) | 0.578 | |

| (3) I have been able to effectively address my mentee’s/mentees’ learning demands in mentoring conversations. | 1.080 (0.075) | 0.695 | |

| (4) My role as a mentor is meaningful to the development of my ECT’s teaching practice. | 1.114 (0.082) | 0.782 | |

| (5) My mentoring has contributed to the pedagogical skills of my mentee. | 1.180 (0.094) | 0.764 | |

| (6) My mentoring has contributed to the behaviour management skills of my mentee. | 1.261 (0.110) | 0.774 | |

| (7) My mentoring has helped my mentee to develop their wider professional skills. | 1.239 (0.103) | 0.783 | |

| (8) My mentoring has helped my mentee to build good social relationships in the school. | 1.290 (0.150) | 0.663 | |

| Satisfaction in teaching | (1) The advantages of being a teacher clearly outweigh the disadvantages. | 1 | 0.821 |

| (2) If I could decide again, I would still choose to work as a teacher. | 1.215 (0.063) | 0.851 | |

| (3) I regret that I decided to become a teacher. * | 1.009 (0.061) | 0.764 | |

| Job satisfaction in school | (1) I would like to change to another school if that were possible. * | 1 | 0.69 |

| (2) I enjoy working at this school. | 0.838 (0.058) | 0.903 | |

| (3) I would recommend my school as a good place to work. | 0.977 (0.065) | 0.882 | |

| Well-being in teaching | (1) I am good at helping pupils learn new things. | 1 | 0.781 |

| (2) I have accomplished a lot as a teacher. | 1.348 (0.124) | 0.778 | |

| (3) I feel like my teaching is effective and helpful. | 1.201 (0.077) | 0.859 | |

| Well-being in school | (1) I feel like I belong at this school. | 1 | 0.837 |

| (2) I can really be myself at this school. | 1.066 | 0.846 | |

| (3) I feel like people at this school care about me. | 0.984 | 0.824 | |

| (4) I am treated with respect at this school. | 0.977 | 0.86 |

| Scale | X2 | df | X2/df | CFI (Robust) | TLI (Robust) | RMSEA (Robust) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.564 | 2 | 0.282 | 1 | 0.999 | 0.016 |

| 1.926 | 2 | 0.963 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.029 |

| 81.053 | 164 | 0.494 | 0.997 | 0.997 | 0.023 |

| 21.245 | 9 | 2.361 | 0.992 | 0.986 | 0.053 |

| 2.039 | 2 | 1.020 | 1 | 1 | 0.033 |

| 1.976 | 2 | 0.988 | 1 | 1 | 0.033 |

| 27.641 | 20 | 1.382 | 0.986 | 0.981 | 0.040 |

| 12.172 | 8 | 1.522 | 0.994 | 0.989 | 0.040 |

| 14.286 | 13 | 1.099 | 0.995 | 0.992 | 0.034 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Learning and engagement with ECF mentoring programme | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| (2) In-school support and development for ECF mentors | 0.368 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| (3) Successful leadership practices–setting directions | 0.102 ** | 0.321 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| (4) Successful leadership practices–developing teachers | 0.144 ** | 0.336 ** | 0.754 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| (5) Successful leadership practices–redesigning the organisation | 0.124 ** | 0.325 ** | 0.735 ** | 0.794 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| (6) Successful leadership practices–improving the teaching programme | 0.142 ** | 0.320 ** | 0.696 ** | 0.825 ** | 0.781 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| (7) Professional growth opportunities | 0.156 ** | 0.398 ** | 0.582 ** | 0.711 ** | 0.645 ** | 0.624 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| (8) Collaborative culture | 0.137 ** | 0.303 ** | 0.620 ** | 0.659 ** | 0.698 ** | 0.636 ** | 0.680 ** | 1 | |||||||

| (9) Mentors’ workload conditions | 0.179 ** | 0.457 ** | 0.512 ** | 0.604 ** | 0.598 ** | 0.598 ** | 0.691 ** | 0.672 ** | 1 | ||||||

| (10) Self-efficacy as a mentor | 0.245 ** | 0.314 ** | 0.230 ** | 0.249 ** | 0.210 ** | 0.253 ** | 0.232 ** | 0.204 ** | 0.189 ** | 1 | |||||

| (11) Satisfaction in teaching | 0.161 ** | 0.290 ** | 0.263 ** | 0.270 ** | 0.276 ** | 0.236 ** | 0.373 ** | 0.337 ** | 0.397 ** | 0.166 ** | 1 | ||||

| (12) Job satisfaction in school | 0.081 * | 0.316 ** | 0.572 ** | 0.572 ** | 0.532 ** | 0.452 ** | 0.587 ** | 0.603 ** | 0.493 ** | 0.169 ** | 0.437 ** | 1 | |||

| (13) Well-being in teaching | 0.111 ** | 0.197 ** | 0.352 ** | 0.373 ** | 0.366 ** | 0.336 ** | 0.402 ** | 0.378 ** | 0.350 ** | 0.331 ** | 0.358 ** | 0.352 ** | 1 | ||

| (14) Well-being in school | 0.115 ** | 0.323 ** | 0.544 ** | 0.540 ** | 0.535 ** | 0.449 ** | 0.667 ** | 0.652 ** | 0.555 ** | 0.183 ** | 0.429 ** | 0.741 ** | 0.524 ** | 1 | |

| (15) Destination | 0.035 | −0.025 | −0.123 ** | −0.142 ** | −0.127 ** | −0.085 * | −0.136 ** | −0.061 | −0.043 | 0.037 | −0.110 ** | −0.281 ** | −0.012 | −0.188 ** | 1 |

| Mean (SD) | 40.28 (10.16) | 40.25 (10.17) | 50.33 (0.89) | 40.92 (10.08) | 40.94 (0.99) | 40.68 (10.13) | 40.75 (0.97) | 50.14 (0.85) | 40.49 (10.08) | 50.43 (0.57) | 40.74 (10.20) | 40.95 (10.11) | 50.61 (0.54) | 50.22 (0.91) | - |

| Reliability α | 0.869 | 0.804 | 0.940 | 0.933 | 0.909 | 0.921 | 0.876 | 0.843 | 0.879 | 0.887 | 0.854 | 0.835 | 0.838 | 0.908 | - |

| Imputation | X2 | df | p | X2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4158.86 | 1929 | 0 | 2.16 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.054 |

| 2 | 4141.608 | 1929 | 0 | 2.15 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.054 |

| 3 | 4155.395 | 1929 | 0 | 2.15 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.054 |

| 4 | 4122.273 | 1929 | 0 | 2.14 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.037 | 0.054 |

| 5 | 4175.25 | 1929 | 0 | 2.16 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.055 |

| 6 | 4182.104 | 1929 | 0 | 2.17 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.055 |

| 7 | 4184.85 | 1929 | 0 | 2.17 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.055 |

| 8 | 4161.23 | 1929 | 0 | 2.16 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.055 |

| 9 | 4158.213 | 1929 | 0 | 2.16 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.055 |

| 10 | 4124.104 | 1929 | 0 | 2.14 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.054 |

| 11 | 4152.373 | 1929 | 0 | 2.15 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.055 |

| 12 | 4142.722 | 1929 | 0 | 2.15 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.054 |

| 13 | 4150.603 | 1929 | 0 | 2.15 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.054 |

| 14 | 4117.086 | 1929 | 0 | 2.13 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.037 | 0.054 |

| 15 | 4153.187 | 1929 | 0 | 2.15 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.055 |

| 16 | 4190.196 | 1929 | 0 | 2.17 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.055 |

| 17 | 4171.074 | 1929 | 0 | 2.16 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.055 |

| 18 | 4167.009 | 1929 | 0 | 2.16 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.055 |

| 19 | 4165.225 | 1929 | 0 | 2.16 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.054 |

| 20 | 4093.029 | 1929 | 0 | 2.12 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.038 | 0.054 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gu, Q.; Leithwood, K.; Eleftheriadou, S.; Baines, L. How School Leaders Retain Experienced and Capable Teacher Mentors. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010014

Gu Q, Leithwood K, Eleftheriadou S, Baines L. How School Leaders Retain Experienced and Capable Teacher Mentors. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Qing, Kenneth Leithwood, Sofia Eleftheriadou, and Lisa Baines. 2026. "How School Leaders Retain Experienced and Capable Teacher Mentors" Education Sciences 16, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010014

APA StyleGu, Q., Leithwood, K., Eleftheriadou, S., & Baines, L. (2026). How School Leaders Retain Experienced and Capable Teacher Mentors. Education Sciences, 16(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010014