Abstract

This study explored dynamic assessment (DA) of writing in a linguistically and culturally diverse context. Drawing on conceptualizations of DA and ecological languaging competencies (ELC), an ELC-based Loop Pedagogy was designed and adapted in a primary English language teaching (ELT) classroom aiming to foster ongoing development of a dynamic, dialogic, and differentiated assessment approach. A mixed methods research design was adopted with data sources including questionnaires, lesson observations, interviews, and documents/artifacts of student works. Research findings indicated that with optimized choices of learning, timely scaffolding, personalized written feedback, as well as a caring and supportive environment, students with diverse learning needs improved their writing abilities, enhanced their language awareness, and increased their positive affect toward writing activities.

1. Introduction

Amidst global complexity and instability in the 21st century, education worldwide advocates sustainable quality education for diversity, equity, and inclusion (United Nations, 2015). In English-as-an-additional-language contexts, although students bring with them a wide range of languages, knowledges, as well as semiotic and cultural resources, their academic performance is assessed through a narrow, monolingual (e.g., English-only) lens which is misaligned with their dynamic and strategic deployment of multiple languages and semiotic resources in classroom meaning-making. There is an urgent need for valid and inclusive assessments that effectively evaluate students’ knowledge and abilities in multilingual education (e.g., Kelly & Stewart, 2025). Translanguaging (García & Li, 2014) and trans-semiotizing (Lin, 2015) have been recommended as promising approaches to designing and implementing inclusive assessments for multilingual learners (He & Lin, 2021; Kelly & Stewart, 2025; Larsen-Freeman, 2018; Lin et al., 2020; Shohamy, 2011).

While translanguaging is increasingly applied in multilingual education, Li and García (2022) problematized the code-view of language and emphasized that translanguaging is “a unitary repertoire” rather than code-switching. Li (2024) argued that translanguaging can be adopted as a transformative pedagogy for inclusion and social justice and advocated for a change in teachers’ and students’ mindsets through “co-learning” and “transpositioning”. Nevertheless, even though translanguaging has been progressively embraced by researchers and recommended as being conducive to inclusive assessment, it remains difficult to align translanguaging pedagogy with assessment owing to hindrances arising from dominating monolingual policies and assessment approaches, high-stakes standardized tests, as well as misunderstandings of teachers, students, and other stakeholders (Kelly & Stewart, 2025; Schissel et al., 2021). As Shohamy (2011) noted,

Although dynamic, diverse, and constructive discussions of multilingual teaching and learning are currently taking place within the language education field, the phenomenon is completely overlooked in the assessment field that continues to view language as a monolingual, homogenous, and often still native-like construct. There seems to be a lack of coordination between the two disciplines of teaching and testing.(p. 419)

In the sociocultural perspective of second language development, dynamic assessment (DA) has been proposed as an approach which “overcomes the assessment–instruction dualism” (Poehner, 2008, p. 24). Rooted in Vygotsky’s (1978) theory of mind, DA is interpreted as “a framework for conceptualizing teaching and assessment as an integrated activity of understanding learner abilities by actively supporting their development” (Lantolf & Poehner, 2011, p. 11). DA has served as an important tool to promote inclusive practices and improve student learning (Le et al., 2023). In second language education, (Computerized)DA has been reported to be beneficial for reinforcing students’ learning and motivation (Alsaadi, 2021) and effective in promoting their development of second language knowledge and skills (Lantolf & Poehner, 2011; Rashidi & Bahadori Nejad, 2018; Yang & Qian, 2023). However, despite increasing implementation of DA, there remains a pressing need for empirical research into classroom-based assessment strategies that effectively foster second language development, especially in theorization of assessment practices; as pointed out by Poehner and Inbar-Lourie (2020), “conceptual frameworks for appraising specific assessment practices and determining how they may be developed has remained elusive” (p. 7).

Building on the DA theories, this study explored the integration of teaching and assessment in the writing instruction of a culturally and linguistically diverse English language teaching (ELT) classroom. To design valid and culturally responsive assessment, the researchers explored theorization, which captures the complexity and dynamic interactions between individuals and artifacts in multilingual education contexts. As Shohamy (2011) suggested, for assessments to be “construct-valid”, they need to be based on “a construct that follows current understandings and theories of language” (p. 420). Accordingly, assessment designs need to consider fundamental questions such as what it means to know a language, how language should be taught in multilingual contexts, what objectives learners should achieve, and how to evaluate whether learners have achieved the learning objectives. This research addressed these questions through the lens of “ecological languaging competencies” (ELC) (The New Territories Group, forthcoming) and adopted the ELC-based Loop Pedagogy (Thibault, 2024) to examine the unity of instruction and assessment in multilingual and multicultural educational ecology. This study concluded with researchers’ reflection on the praxis of second language classroom assessment (Poehner & Inbar-Lourie, 2020) through a combination of the theory/research and practice in teacher–researcher collaborative action research.

2. Theoretical Framework

To cope with challenges facing second language education, Larsen-Freeman (2018) advocated for an ecological approach to future second language education and research which highlighted the complexity and dynamism of contexts, learners, and pedagogy to help learners adapt to learning contexts and employ affordances to increase learning access. This study conceptualized language learning, teaching, and assessment through the ELC lens, which is grounded in theorization distinct from traditional paradigms. This section first introduces the conceptualization of ELC, including core concepts such as “languaging” (cf. language), “competencies” (cf. competence), and “socio-ecological world”, as well as its relation to the ecological psychological view of learning and the recent views of second language assessment. It then elaborates on the conceptual framework of ELC-based integration of Loop Pedagogy and DA with components of the framework and the three stages of the Loop Pedagogy described in detail.

2.1. ELC

A distinctive feature of ELC is its interpretation of “language” as verb-like rather than as a noun, emphasizing languaging as dynamic activities rather than static codes. Unlike traditional code-views which see language as a bounded system of static pre-existing entities, the ELC perspective reimagines “languaging” as what people do in human ecology in flows of dynamic, embodied, and socially situated activities. The ELC framework is underpinned by three key concepts: whole-body sense-making, first-order languaging vs. second-order language, and socio-ecology of communication.

According to Thibault’s (2021) distributed language view, “Languaging is a form of whole-body sense-making…The sensed unity of experience is in the first instance grounded in the self’s felt, embodied experience of itself as a bodily unity that is the deictic source of its actions” (p. 68). During languaging, individuals actively participate in meaning-making through integrating emotions, actions, and interactions with people and artifacts in socio-ecological systems where meaning emerges from mutual engagement of the body, mind, and environment. The feelings and emotions of an individual affect and are affected by those of other agents and agencies. They have the capacities to increase and decrease the body’s power to act (Thibault, 2021). Hence, affects are the motives that activate individuals’ agency as a driving force in their embodied actions embedded in the socio-ecological system.

To understand ELC, it is essential to distinguish between the two dimensions of human languaging—“first-order languaging” and “second-order language” (Thibault, 2011). The former refers to the real-time, embodied engagement with what is happening here and now (i.e., what people are doing now), which focuses on the dynamic integration of affordances (i.e., entities perceived as opportunities for actions in contexts) for meaning-making, including gestures, artifacts, texts, technologies, and so on, in the immediate environment, while the latter involves more abstract patterns (i.e., the conventional thinking of languages as abstract entities like pronunciation, vocabulary, and lexicogrammar in dictionaries or grammar books) that are sedimented and conventionalized under long cultural and historical timescales as part of the community heritage and traditions that people draw on during languaging. It is crucial that the two dimensions of human languaging are in ongoing synergistic interaction, that is, “meshing” with each other. As the interview below elaborates,

…we draw on these patterns that originate from these cultural, historical timescales that did not originate in the here and now… So we draw on and we adaptively modify them to suit present circumstances so that it’s a meshing there of the first and the second orders in what we’re doing… there’s no languaging without the verbal… it’s not just bodies and movement, it’s languaging bodies, basically engaging with aspects of the human world.(TESOL For All (2025), February 19, https://youtu.be/YfYdMN3HI6o?si=MRl5n9QNMVQ0qNnj (accessed on 20 November 2025))

Persons with whole-body sense-making capacities and agency are themselves the “mediators” between the two orders. The persons’ first-order languaging, namely, their active participation in a community of practice as social agents and their dynamic engagement with various aspects in the human ecology give rise to various second-order phonological and lexicogrammatical patterns which provide conventionalized solutions to persons’ goals and needs. Hence, during ongoing alignment and coordination of the two orders, first-order languaging is the driving force for the emergence of second-order lexicogrammatical rules and patterns (The New Territories Group, forthcoming).

It should be noted that ELC requires a socio-ecological world in relation to which languaging competencies can be exercised. Languaging is part of how people operate as human agents in the world, which encompasses both the natural domain (i.e., humans exist in the biological world as embodied beings) and the cultural domain (i.e., humans are cultural beings inhabiting the human ecology) (TESOL For All, 2025). Communication does not occur in isolation but is embedded within dynamic, dialogic, and diversified socio-ecological systems that include communities of practice, artifacts, and communication agents and objects. Effective communication requires situational awareness, adaptability, and the ability to coordinate with both people in the community of practice and affordances in the socio-ecological system. Such an ecological perspective is well reflected in ecological psychology which conceptualizes learning as “extended” in a large and open-ended learning environment, with surroundings which students can perceive and act on. Accordingly, language education should not only “connect people, places, and resources”, but also “cultivate a learning environment for students to conduct meaningful activities” (Paul et al., 2023, p. 204).

Another important distinction between the ELC framework and traditional language education theories is the notion of “competencies”. In second language education “communicative competence” (Hymes, 1964/1972) has been the teaching objective for decades with the notion “competence” derived from Chomsky’s (1965) formal linguistics and defined as the speaker-hearer’s knowledge of language (i.e., rule-based knowledge of grammatical structures)—the underlying mental reality located in the speaker-hearer’s brain. The ELC perspective disagreed with Chomsky’s interpretation of competence and argued that a person’s mental reality is not located in his brain/mind but is exercised in the social world. Rather than using “competence”, the term “competencies” was adopted in the ELC framework, which elucidated that languaging competencies are not about grasping the rule-based knowledge of phonological and lexiogrammatical structures existing inside individuals’ underlying mental realities, but are diachronically emergent through individuals’ active participation in practices that are constrained by the requirements of particular tasks (The New Territories Group, forthcoming). The notion of languaging competencies thus echoes Larsen-Freeman’s (2015) view of second language development:

After all, we don’t only teach language, we teach learners. And teaching a language does not involve the transmission of a closed system of knowledge. Learners are not engaged in simply learning fixed forms or sentences, but rather in learning to adapt their behavior to an increasingly complex environment.(p. 502)

The ELC perspective of language education resonates with the ecological psychological view of learning which regards learning as a process of attunement—“education of intention and attention” (Young, 2004, p. 172). For example, Paul et al. (2023) proposed three ecological principles for designing online teaching of Chinese as a foreign language. These ecological principles include “perception and action cycles”, “intention and attention merge” (Young, 2004), and “meaning-making and values-realizing coincide” (Zheng, 2012) in an ecosystem. Informed by these principles, language teachers may design activities that situate learning in physical environments that engage perception–action cycles, provide scaffolding for attuning students’ intention and attention, and cultivate curiosity and awareness about meaning-making, value realization, and care for self, others, and the environment. These ecological principles provide promising directions for design and implementation of the ELC-based synergy of Loop Pedagogy and DA.

As languaging competencies always emerge in a dynamic process of socially situated activities, the ELC perspective argues that, rather than assessing competence of individual student’s rule-based knowledge of the target language through standardized tests, ELC-based language assessments should encompass multimodal and embodied ways of meaning-making and focus on how students fulfill tasks by integrating both verbal (e.g., lexicogrammatical patterns and genre structures) and non-verbal (e.g., multimodalities, gestures, and body movements) communication effectively and adapting to the situational demands of diverse communicative tasks. Such a view of second language assessment also resonates with Larsen-Freeman (2018), who advocated for abandonment of traditional monolingual policies, standardized assessments, as well as static notions of competence in acquiring lexicogrammatical rules, and emphasized the need to evaluate students’ actual performance, namely, what students are able to do and how well they complete the task through translanguaging rather than how well they utilize one of their languages.

2.2. ELC-Based Integration of Loop Pedagogy and DA

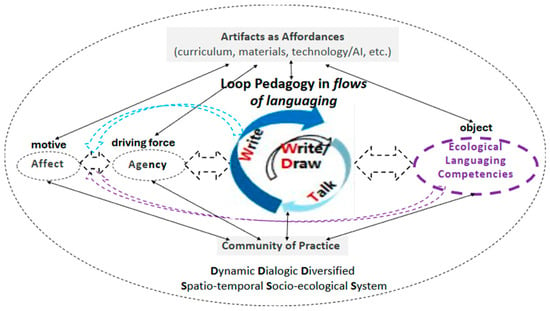

Drawing on theorization of ELC and DA, the teaching and assessment of writing in multilingual and multicultural classrooms are integrated and embedded in a dynamic, dialogic, diversified, spatio-temporal, and socio-ecological system (Figure 1). Students practice writing as a communication task in ELT classrooms with their teacher and peers as a community of practice. The curriculum, textbook, and teaching materials (e.g., PowerPoint slides, worksheets, Post-it notes, scenario cards, etc.) as well as various artifacts in the classroom (e.g., blackboard, visualizer, iPads, e-learning apps, etc.) form a learning environment and provide affordances for writing activities. The objective of ELT writing is not just the verbal accuracy of students’ writing, but their ability to fulfill communication tasks through ongoing embodied actions in flows of languaging (e.g., write/draw a text, talk about it in groups, and improve it according to feedback from the community). Hence, the assessment criteria of the writing task should focus on not only the accurate use of linguistic rules and patterns but also the dynamic communication process of whole-body sense-making when students creatively utilize both verbal and non-verbal semiotic resources to express their thoughts (e.g., translanguaging and trans-semiotizing), engage in dialog with the teacher and peers, and search for information from potential affordances such as textbooks, (e-)dictionaries, and artificial intelligence (AI) (e.g., Zoom with AI assistance). Unlike traditional standardized tests which evaluate students’ performance in one single attempt, ELC-based writing teaching adopts the DA approach (Poehner & Lantolf, 2005, 2024) which is not static but interactive and process-oriented, aiming to identify students’ learning difficulties and potential and providing timely and tailor-made scaffolding by integrating instruction and assessment in a dynamic process.

Figure 1.

DA of writing through ELC-based Loop Pedagogy.

As illustrated in Figure 1, the ELC-based DA approach can be reflected in Thibault’s (2024) three-phase Loop Pedagogy. In Phase 1, students write/draw on a topic without prior preparation. The topic selected is related to students’ own experiences. The same topic is adopted to form a basis for comparing results. In Phase 2, students talk in groups about the same topic written/drawn in Phase 1. The talk is recorded by Zoom, which generates transcripts of the recording. Facilitators (e.g., teacher or tutor) join different groups as sympathetic listeners, providing supportive suggestions occasionally without explicitly directing or evaluating the students’ talk. The supportive suggestions include prompts, hints, or feedback. Facilitators then check the Zoom-generated transcripts of students’ talks. Based on the transcripts, they provide tailor-made written feedback for students to reflect on and then re-shape the transcript into a piece of writing in Phase 3. Students are provided with their writing/drawing drafts in Phase 1 and a transcript of their talk in Phase 2 with relevant written feedback. Based on facilitators’ written feedback, the teacher guides students to reflect on their performance in Phase 1 and Phase 2. Students are encouraged to build on their previous efforts and what they have learned from the feedback. The focus is not on correcting language “errors” but on how to develop as an effective communicator. After co-reflection, students then produce a final written draft of the same topic.

Grounded in the conceptual framework, this study addressed the following research questions:

- How did the ELC-based Loop Pedagogy impact students’ writing development in a culturally, linguistically, and cognitively diverse ELT classroom?

- How did the teacher and student participants perceive the effects of the ELC-based Loop Pedagogy on ELT writing? Why?

3. The Study

This research was part of a collaborative project involving researchers, teachers, and students at a multicultural and multilingual primary school in Hong Kong. The school aims to foster harmonious relationships within the community and create an inclusive school culture and supportive learning environment. Both the principal and the participating teacher were positive about transformations in plurilingual assessment, but they were concerned about students’ performance in high-stakes assessments, which are traditional standardized tests evaluating students’ mastery of rule-based language knowledge. The school adopts English-medium instruction; however, due to diversity in language proficiencies, not all students are confident about speaking in English. This becomes more obvious in writing, as most students find it difficult to write in English.

A mixed methods research design (Creswell, 2009) was adopted to explore how the ELC-based Loop Pedagogy affected students’ writing development. The teacher, Miss Chan (pseudonym; all names of the teacher and students in this study are pseudonyms), and 26 students in her Primary 6 class participated in the research. As Miss Chan had maintained a collaborative relationship with the researchers, she was able to understand the research objective and the pedagogy after the first co-planning meeting. Miss Chan had taught the students English for five years; she knew the students well and the students had adapted to her teaching pedagogy.

The field work included pre- and post-intervention questionnaires, videotaped lesson observations, post-intervention audiotaped interviews, and documentation of student works at different stages with relevant teacher/tutor feedback. The field work was carried out in three phases—pre-intervention, during intervention, and post-intervention—with ongoing data analysis at different phases. The multiple data collection methods, multiple data sources, multiple participants, and different investigators enabled the researchers to confirm their research findings (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). The data collected from different sources (e.g., student responses to the pre- and post-intervention questionnaires, lesson observation videos, interview recordings, documents/artifacts of student works and teaching materials, etc.) allowed the researchers to triangulate their data analysis. The post-intervention interviews with the students and the teacher enabled the researchers to not only probe participants to elaborate on their perceptions of the Loop Pedagogy but also allowed the researchers to conduct member checks about their data analysis. The regular research team meetings during the data collection also allowed researchers to conduct peer reviews of the ongoing data analysis.

4. Findings

This section describes the procedure of the field work and presents the corresponding research findings from the pre-intervention to post-intervention stages.

4.1. Pre-Intervention Survey

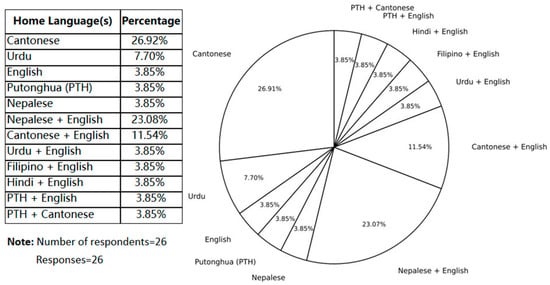

Before intervention, a mini survey was administered to collect background information about the students and the ELT practice. Analysis of students’ home languages indicated a culturally and linguistically diverse landscape (Figure 2). Seven languages were found to be spoken in the families of the 26 respondents. Around half the families spoke some English, but the other half did not have any exposure to English.

Figure 2.

Summary of home languages.

The results of the Likert scale questionnaire (Table 1) indicated that students tended to be positive about English learning (M = 3.92, SD = 0.93), especially through online activities and using iPads. They seemed to be more confident in English speaking (M = 3.96, SD = 1.00) but relatively less confident in writing (M = 3.50, SD = 1.14). They tended to resort to drawing (M = 3.77, SD = 1.31) rather than using other languages or gestures when they could not access and meet the demands of English writing. They did not seem to find the school English tests difficult but wished to have other approaches to assess their English proficiency (M = 3.46, SD = 0.99).

Table 1.

Results of pre-intervention questionnaire.

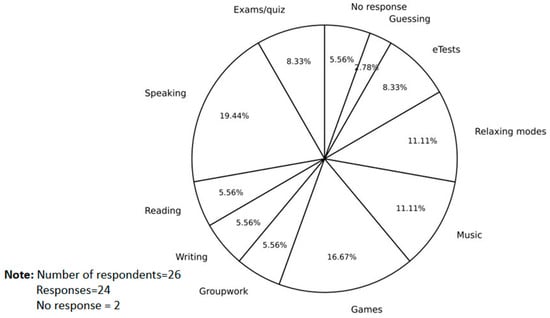

A total of 24 out of the 26 students responded to the open-ended question “If you could choose a different way to test your English, what way would you prefer?”. The respondents’ preferences for test modes are summarized in the pie chart below.

Figure 3 displays a wide range of assessment mode preferences. Some students preferred more relaxing test styles such as games (16.67%), music (11.11%), relaxing modes (11.11%), e-tests (8.33%), and groupwork (5.56%), while other students preferred more conventional modes such as an exam/quiz (8.33%), speaking (19.44%), reading (5.56%), and writing (5.56%). The results echoed those of the Likert scale questionnaire finding that students tended to be more confident about speaking than writing in English. To build up students’ confidence, the researchers selected English writing as the focus of the Loop Pedagogy during the intervention.

Figure 3.

Preferences for assessment modes.

4.2. During-Intervention Classroom Ethnography—The Loop Pedagogy

Guided by the Loop Pedagogy, the researchers and Miss Chan co-planned the lessons. As students were to learn storybook Bullying, and as writing in high-stakes exams was usually conducted in a four-picture format, students would write a short essay about “a bullying behavior” according to a scenario card provided. Instead of conducting the writing in one lesson as normally practiced, students would finish the writing task in three phases. The Loop Pedagogy was incorporated into the regular teaching plan, during which Miss Chan recapped a previously learned topic “Mean on Purpose or Friendship Fire?”, then she guided students to read the new story section by section and to finish worksheets on knowledge points in the story.

4.2.1. Phase 1: Write/Talk

The teaching of writing guided by the Loop Pedagogy started after students had finished reading the storybook and completed the corresponding exercises. In Phase 1, as students needed to finish the task without preparation, they were allowed to select writing or drawing. After Miss Chan introduced the task, she distributed a scenario card with a writing worksheet or a comic strip template to the students who then wrote a short essay or drew a comic strip about bullying behavior by themselves.

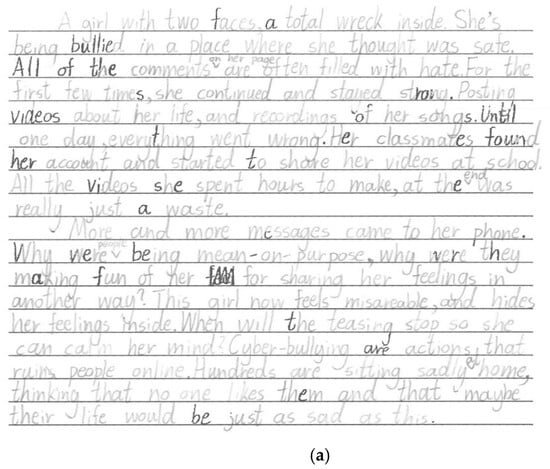

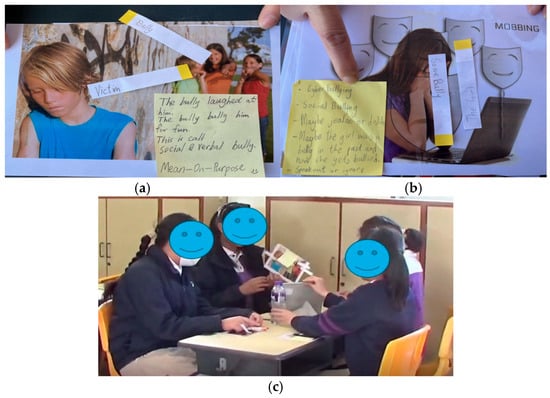

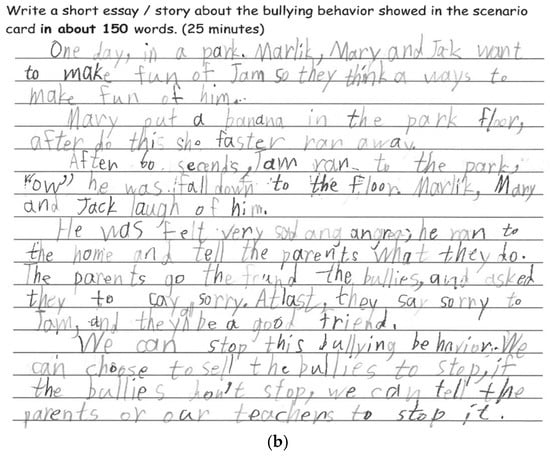

Six short essays and twenty comic strips (draft 1) were collected in Phase 1. This echoed the pre-intervention questionnaire results which found that most students were not confident in English writing and preferred to draw when they found it difficult to write in English. Comparing students’ draft 1, researchers found that students of linguistically more advanced levels tended to select writing and write relatively longer texts, students at developing levels preferred to draw a comic strip which consisted of more verbal information, and foundational level students tended to resort to drawing with only a few words expressing the speech or thoughts of characters. Figure 4a,b show the draft 1 by Winnie, whose English proficiency belonged to an advanced level (Figure 4a—top) and the work by Eva, whose English proficiency remained at a foundational level (Figure 4b—bottom).

Figure 4.

The draft 1 work of students whose English proficiencies were at advanced level (a—top) and foundational level (b—bottom).

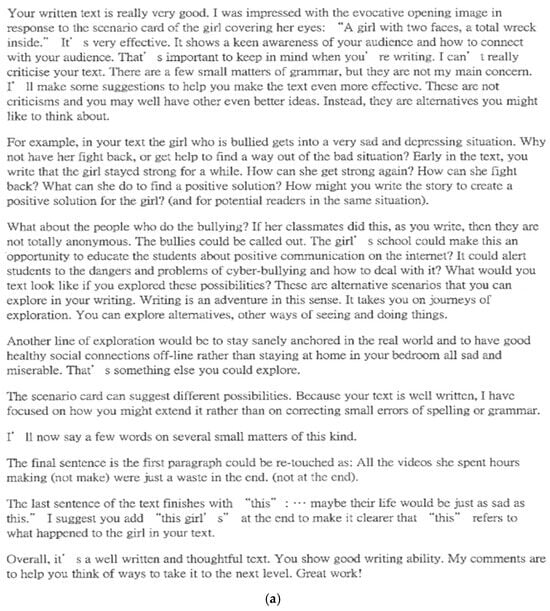

4.2.2. Phase 2: Talk

In Phase 2, Miss Chan arranged students into groups to discuss the scenario cards according to the question prompts provided. She also provided students with some Post-it sticky notes to label the “bullies” and “victims” in the scenario cards and note down some key points for discussion (Figure 5a—top-left and Figure 5b—top-right). Then each group member talked about (but did not read out) their essay/story written/drawn in Phase 1 for around three minutes. Their talk was recorded by Zoom on an iPad. The groupmates and tutor (i.e., a researcher in this study) sat in groups listening attentively and raising questions occasionally to help students maximize their talk (Figure 5c—bottom).

Figure 5.

(a–c) Scenario cards, sticky notes, and group talk in Phase 2.

Due to the difficulty of talking and the diversity of language proficiency among group members, students were allowed to use their more familiar languages (e.g., Putonghua or Cantonese) and ask peers for help (e.g., Cathy helped Eva translate the researcher’s questions) when they had difficulty continuing their talk. Below shows an excerpt of the dialog between groupmates (Eva, Cathy, and Crystal) and the researcher.

- Cathy:

- 她意思是,說這個故事,在三分鈡内。 [Putonghua: She meant, tell this story, in three minutes.]

- Eva:

- Um. One day. Er. One…

- Researcher:

- Louder. Louder (As there were three groups performing the talking task simultaneously in the classroom, the researcher encouraged students to speak louder to ensure the recording by Zoom was as clear as possible.). 大聲點。 [Putonghua: Louder please.].

- Eva:

- One day, a people put the banana in the floor. And he run away. And, a, a boy is come to the floor.

- Researcher:

- Mm-hmm.

- Eva:

- And, and he fall down. And… And…

- Researcher:

- Mm-hmm. The boy fell down.

- Eva:

- Fell down.

- Researcher:

- Uh-huh.

- Eva:

- And, put the banana. The people laugh at him, and he very sad.

- Researcher:

- Uh-huh. People laughed at the boy.

- Eva:

- En.

- Researcher:

- And the boy felt very sad.

- Eva:

- En.

- Researcher:

- And then? What happened?

- Eva:

- Er. And then… Er. And then his family come.

- Researcher:

- Uh-huh.

- Eva:

- And to tell the bullies to say sorry.

- Researcher:

- Uh-huh.

- Eva:

- So he is happy now.

- Researcher:

- Mm-hmm. So who is the bully and who is the victim?

- Eva:

- Er. Bully is some bullies.

- Researcher:

- Mm-hmm. Some bullies.

- Eva:

- The victors [sic victim] is Jay.

- Researcher:

- The victim is Ja, Jack? Jim?

- Eva:

- Jim.

- Researcher:

- Jim. Uh-huh. The victim is Jim, who slipped down.

- Eva:

- Er. Jim.

- Researcher:

- Yeah. You do not know the name of the bully? But just someone?

- Eva:

- En.

- Researcher:

- Okay. Very good.

- … …

- Researcher:

- What do you think of the reason for the bullying behavior in your story? What’s the reason?

- Cathy:

- 在你故事裏的那個霸凌者,欺負人的那個人,在你故事裏面. [Putonghua: In your story, the bully, the one who bullied others, in your story.]

- Crystal:

- 爲什麽要欺負他呢?[Putonghua: Why did he bully him?]

- Cathy:

- 你覺得你故事裏面的那個人爲什麽要欺負這個人? [Putonghua: In your opinion, why did the person in your story bully this boy?]

- Eva.:

- 故事裏面… [Putonghua: In the story…]

- Researcher:

- 大聲點。 [Putonghua: Louder.] Louder please. Why?

- Cathy:

- 爲什麽? [Putonghua: Why?]

- Eva:

- Because the bully is bad.

- Researcher:

- Mm-hmm. The bully is bad. Then why did the boy do such a bad thing?

- Cathy:

- 就是爲什麽這個霸凌者要欺負這個男生? [Putonghua: That means, why did the bully bully this boy?]

- Researcher:

- 爲什麽會有霸凌? [Putonghua: Why did the bullying happen?]

- Cathy:

- 爲甚麽他想要欺負這個男生? [Putonghua: Why did he want to bully the boy?]

- Crystal:

- 欺負這個男生的原因是什麽? [Putonghua: What’s the reason for bullying this boy?]

- Eva:

- Er. 這個人欺軟怕硬. [Putonghua: The person bullies the weak and fears the strong.]

- Researcher:

- 欺軟怕硬? [Putonghua: Bully the weak and fear the strong?]

- Cathy:

- The, the bully, er, the bully like to bully someone, who is, the age is smaller than him.

- Researcher:

- Yes. Someone who is timid. Okay. Uhm. Very good.

- … …

- Researcher:

- How did the victim feel in your story? 嗰個受害人,佢係乜嘢感受啊? [Cantonese: The victim. How does he feel?]

- Eva.:

- Er. He feel sad.

- Researcher:

- Oh. He feels sad. Besides sad, what else?

- Eva.:

- Er. Angry.

- Researcher:

- Angry. Sad and angry. That’s a good word.

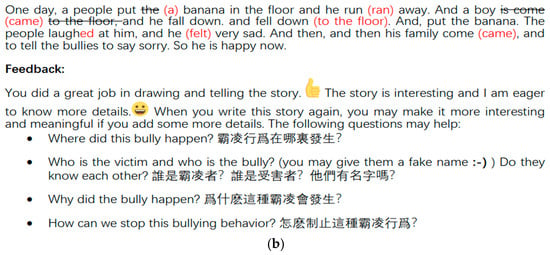

After the lesson, researchers generated the transcripts of student talks (draft 2) and provided personalized feedback according to students’ draft 1 and draft 2. While advanced learners tended to talk more fluently and provide more detailed texts, foundational learners were only able to utter some sentences with scaffolding from tutors or peers. Advanced learners generally completed the whole text with fewer linguistic mistakes, hence the researcher feedback tended to focus more on improving content or writing skills (e.g., feedback to Winnie in Figure 6a—top). Most developing learners were able to present an entire essay, but needed to improve their work in different aspects. Instead of correcting all mistakes, the researchers focused on aspects that most affected communication and the most typical errors. As foundational learners had difficulty finishing their writing, the feedback during the talk (e.g., groupmates’/researcher’s scaffolding to Eva) and that provided on the transcripts (e.g., researcher feedback to Eva in Figure 6b—bottom) was translanguaging and trans-semiotizing, with examples focusing on how to communicate effectively rather than how to use lexicogrammatical rules correctly.

Figure 6.

Feedback on writing/talk by Winnie (a—top) and Eva (b—bottom).

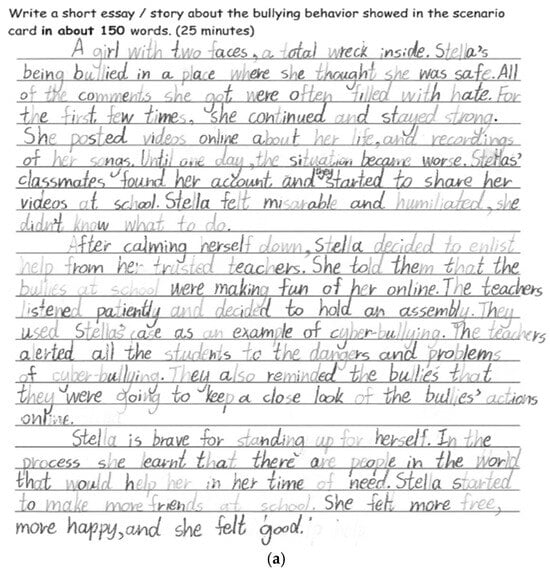

4.2.3. Phase 3: Write

In Phase 3, students were assigned to write the same essay/story again. Before writing, Miss Chan guided them to reflect on what they had written/talked about and how they could improve their writing based on tutors’ feedback.

Analysis of draft 3 revealed that all students were able to finish their writing in Phase 3. As exemplified in Figure 7a,b, foundational learners were able to write a longer and better organized passage with more details than those provided in their talk in Phase 2 (draft 2) (e.g., Eva’s work in Figure 7b—bottom), while advanced students improved the quality of their writing (e.g., Winnie’s work in Figure 7a—top). Developing students were able to convert the comic strip into a passage with a proper text structure and improved lexicogrammatical accuracy.

Figure 7.

Draft 3 by Winnie (a—top) and Eva (b—bottom).

4.3. Post-Intervention Survey and Interviews

To explore participants’ perceptions of the impact of the Loop Pedagogy, the researchers administered a post-intervention survey among the students and interviewed Miss Chan and six students of different language proficiency levels. The interview was conducted in English, but the informants could use their home language when necessary.

4.3.1. Questionnaire

As results of the post-intervention questionnaire (Table 2) indicated, students of diverse learning needs enhanced their writing and speaking skills, language awareness, and learning attitudes to various degrees.

Table 2.

Results of post-intervention questionnaire.

Data analysis indicated that students tended to believe they were able to write/draw the story in Phase 1 (M = 4.23, SD = 0.71), talk about their story (M = 3.88, SD = 1.03), and enhance their spontaneous speaking ability in Phase 2 (M = 3.88, SD = 0.86). They found that the researchers’ written feedback (M = 4.00, SD = 0.88) and peer feedback (M = 3.73, SD = 1.04) helped them to refine both their writing and speaking skills. The students also found that their final writing in Phase 3 improved (M = 4.19, SD = 0.90), with raised awareness of both lexicogrammatical knowledge (M = 3.92, SD = 0.89) and writing skills (M = 3.96, SD = 1.04). They felt more confident in writing in Phase 3 (M = 4.08, SD = 0.89) and hoped that their teachers would adopt the Loop Pedagogy in future English lessons (M = 3.46, SD = 1.21).

4.3.2. Interviews with Teacher and Students

The questionnaire results were corroborated by participants’ reflections during the post-intervention interview. Students of different proficiency levels believed that the Loop Pedagogy had helped them improve their writing, which increased their confidence in fulfilling communication tasks. For example, advanced students like Winnie and Anne both found researchers’ “comments” and “tips” helpful for developing writing skills and reminding them of the importance of lexicogrammar.

“Yeah (The pedagogy is helpful). I think I improve my writing skills from the professors’ tips.”(Anne)

“I love the comments professors gave me. They helped me improve my writing skills a lot…. Those (comments on lexicogrammar) are important for essays. We need to also focus on that as well.”(Winnie)

As for developing students, Cathy focused on grammar, as she “made most mistakes in tenses” and the feedback raised her awareness about grammar during writing, while Helen found the feedback improved her writing skills but hoped that the teacher would provide students with “more space for us (them) to improve” and “not just grammatical”.

“Cantonese: 我覺得嗰張紙 (feedback) 睇翻之後,都可以幫到我哋改進寫作,因為就好似我嗰份,咁我錯得最多就係tenses… 我哋都可以睇下我哋啲位點解會錯,同埋錯係啲乜嘢。咁我哋下次寫翻就唔會再重犯。”

[Translation: After reading the (feedback) sheet, I found it helpful for improving our writing. Like my work, I made most mistakes in tenses…We can see what mistakes we’ve made and why we made them, so that we won’t make the mistakes again next time.](Cathy)

“I think it improved my writing skills, and I hope, like in the future, Miss Chan also give us more feedback, more detailed feedback, like, there will be more space for us to improve, not just grammatical. That’s important.”(Helen)

Similarly, foundational students like Edward and Eva found the Loop Pedagogy helpful for improving not only writing but also language learning. For example, Edward explained that he “added some writing” in his drawing which also helped him “improve my (his) writing skill”. Like Cathy, he found the feedback a “helpful” reminder of the lexicogrammar mistakes in his writing.

“…Because when I draw, I also add some writing in it, and it helps me improve my writing skill…I think it’s very helpful because when I look at the feedback, I know what grammar mistake do I make, and spelling mistake, and next writing, I can 糾正翻咯,啲錯誤 [correct the mistakes].”(Edward)

Like her peers, Eva also found the feedback “helpful” and that it offered her “references” about the key elements in story writing. She found the writing task “not difficult”, but “meaningful”, “interesting”, and “helpful for my (her) English learning”. The Loop Pedagogy provided her with opportunities to write step by step, namely, to “express ideas by drawing” in Phase 1; “retell the beginning, development, and ending of the whole story” in Phase 2; and provide more details in Phase 3 about “what people say” and clarify important details such as “names of people in the story, and place”.

“Putonghua: (Loop Pedagogy) 不难,有意思,帮到学英语。不难是因为那个我觉得画画很容易表达。有趣是因为画的过程中,就是在创作想象过程中我感到很享受,很快乐……Talk很好。因为就是说的过程中就可以复述整一件故事的起因,经过,和结果…… (Feedback)帮到。因为就是在写的过程中,有些要写人物在说什么话嘛,就是学到很多新的英语单词…… Feedback 能給我參考, 像那种就是加些人物名字会清楚一些。还有地点,我知道要说清楚一些。”

[Translation: (Loop Pedagogy) It’s not difficult, but meaningful and helpful for my English learning. It’s not difficult because I find it easy to express ideas by drawing. It’s interesting because drawing is a process of creating and imagining that makes me feel enjoyable and happy… The talk was good, because I could retell the beginning, development, and ending of the whole story… The feedback helps because when writing, I need to write what people say and I learned many English new words. The feedback offered me references, like, providing names of people in the story, and place too, I knew I needed to make them clear.](Eva)

The interview with Miss Chan revealed the teacher’s perception of the effects of the Loop Pedagogy and her reflection on the feasibility of applying the pedagogy in future teaching. She seemed to be satisfied with students’ performance in Phase 1—“Twenty comics and six writing”—and attributed this to the “low risk” of the task and the “autonomy” offered to students. Her observation of the students’ enjoyment mirrored Eva’s “enjoyable and happy” feeling while drawing in Phase 1.

“They enjoyed that. Because it’s actually low risk… Students have autonomy. They can choose. …Twenty comics and six writing. I think that’s great.”

Miss Chan accredited the design of Phase 2, as she commented, “Phase 2 is actually the activity that I was going to incorporate in my teaching… Students can refer to their own speaking story. That makes Phase 3 easier”. She appreciated the Zoom-generated transcript based on which researchers offered feedback to the students. However, although Miss Chan also designed group discussions in her regular lessons, she regretted that there was “limited time” and a lack of manpower (i.e., researchers as tutors) which did not allow her to provide students with tailor-made feedback, as she emphasized, “Transcript. We had their transcript, and then teachers could give feedback. We don’t have that (in normal teaching).”

Although Miss Chan seemed to acknowledge the teaching designs in Phase 1 and Phase 2, she found writing the same story again in Phase 3 “a repeated task”. This was also echoed by students like Winnie who commented, “This Loop Pedagogy, I think it’s quite fun, but if I keep on doing it, for like a lot of times, I’ll feel bored.” To improve the pedagogy, the teacher suggested embedding Phase 3 writing into the final task of the unit so that “students won’t get bored” and “will have a sense of achievement”.

5. Discussion

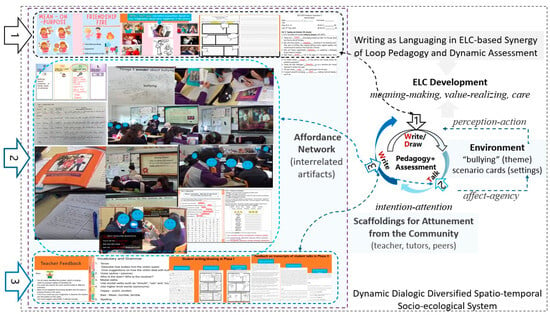

Data analysis indicated the positive impacts of the Loop Pedagogy on students’ writing and the recognition it received from both the teacher and students. This section discusses ELT writing as languaging in ELC-based integration of the Loop Pedagogy and DA (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

ELT writing as languaging in ELC-based integration of Loop Pedagogy and DA.

5.1. Situating Writing in Dynamic and Supportive Environments

Integration of the Loop Pedagogy and DA was exercised in an ELT classroom embedded in a dynamic, dialogic, diversified, spatio-temporal, and socio-ecological system. It started with assigning the task—writing/drawing an essay/comic strip according to the bullying behavior depicted in a scenario card—which situated writing in an environment that engaged students with the theme of “bullying” and the setting in the scenario card. With the situation established, the “perception–action cycle” (Young, 2004) was initiated. The bullying behaviors in the scenario cards (e.g., Figure 5a—top-left and Figure 5b—top-right) were perceived by students. Such felt and embodied experiences became the motive for their actions (i.e., writing or drawing) in flows of languaging as whole-body sense-making (Thibault, 2021). The students’ languaging was shaped by their bodily systems which contributed to both their experiences and their capacities to affect other bodies (e.g., their drawing/writing amused peers) and be affected by others (e.g., convinced by the tutors’/peers’ feedback). Their feelings and confidence about writing/drawing and talking affected their agency to fulfill the communication tasks at different phases. The maximized choices (e.g., writing/drawing, translanguaging and trans-semiotizing, and free grouping) enhanced students’ affects (e.g., motivations and interests), which had the capacity to increase their agency to act (Thibault, 2021). As Anne reflected, ”Loop Pedagogy can capture my classmates’ attention effectively because besides reviewing our stories, my classmates are more comfortable to learn in a group of their choice.” With goals set, the intention to write/draw and talk became clear. Students as agents attended to information relevant to the intentions of their writing/drawing and talking. This contributed to the connection between the “perception–action cycle” and the “intention–attention merge” (Young, 2004). As Gibson (1966) elucidated, “intention gives rise to the perception and action process and in the meantime, perception and action direct and regulate intention” (cited in Paul et al., 2023, p. 195). As intention serves as the driving force of individuals’ behavior and is combined with their values and capacities (Paul et al., 2023), providing students with flexibilities and scaffoldings that activated their familiar experience or prior knowledge (e.g., discussing a previously learned topic) helped to create a “comfortable”, “low risk” environment and a “relaxed atmosphere” to enhance students’ confidence and intention, hence maintaining a dynamic flow of “perception–action cycle” and “intention–attention merge” in the ecosystem.

5.2. Writing as (Trans)Languaging in Affordance Networks with Scaffoldings for Attunement

Classrooms can be adapted to ecosystems that attune perception and action cycles (Paul et al., 2023). With teaching unfolding, the ELT classroom as an ecosystem abounded with affordances and scaffoldings for attunement. People, artifacts, and technology with potential opportunities for actions interacted and interconnected into affordance networks which provided “semiotic budgets” (van Lier, 2000) that led to potential meaningful actions (e.g., PowerPoint slides about a related previously discussed topic, scenario cards, writing/drawing about the topic (draft 1), storybook Bullying, worksheets of lexicogrammar exercises, Zoom on iPad, Post-it notes on scenario cards, transcripts of talks with personalized feedback (draft 2), and teacher summary of drafts 1 and 2 and suggestions for draft 3). Students perceived the affordances, attuned their intention and attention, and then took actions (i.e., write/draw–talk–write) accordingly. At different phases of the Loop Pedagogy, students’ situated, dynamic, embodied, real-time co-actions and integration of affordances in the immediate environment of the classroom (i.e., first-order languaging) were in ongoing synergistic “meshing” with the abstract, long-term sedimented, and conventionalized lexicogrammar patterns and genre structures (i.e., second-order language) which students drew on and adaptively modified to suit the circumstances when fulfilling the actual learning tasks (Thibault, 2021). For example, students perceived the bullying behaviors in the scenarios cards, labeled them with Post-it notes, attended to the relevant language in the storybook/notes, and then selected expressions about people in a bullying situation (e.g., bully and victim) and different types of bullying behaviors (e.g., verbal bullying and cyber bullying), grammar for recounting a past event (e.g., past tense), as well as the genre structure for writing a story (e.g., narration) to fulfil their writing tasks.

Besides interactions between students and artifacts, those between students and other agents in the community of the ecosystem were also essential. In this study, the scaffoldings which the community (e.g., teacher, tutors, and peers) provided to attune students’ intention and attention were constructive and indispensable. This was exemplified by the tutors’ guiding questions and scaffoldings during the talk as well as their feedback and suggestions on the transcripts. According to students’ linguistic and cognitive needs, the oral and written feedback and suggestions were attuned to just-right functional fits (van Lier, 2000) to draw students’ attention to the effective affordances in the environment so that they were able to match the feedback and suggestions with possible actions to fulfill their intentions. Such functional fits were customized to different agents; for example, Eva was suggested to attend to the key elements in a story (i.e., who, when, where, what, and how), Cathy was reminded to attend to the past tense when telling a story, and Winnie was encouraged to attend to other ways of addressing the issue of cyber bullying. With tailor-made attunements, students’ actions (i.e., talking and writing) emerged from the functional fits which empowered them with language awareness and confidence; as Anne elaborated, the tutor’s questions sparked her “creativity” and “imagination” which expanded her vision with “a lot of possibilities.”

5.3. Fostering ELCs with Care

As emphasized by the ecological principles for foreign language education, pedagogical designs should not only cultivate students’ curiosity for and awareness of simultaneous meaning-making and value-realizing in an ecosystem, but also allow for care-taking of oneself, each other, and the environment (Paul et al., 2023). In this study, the integration of the Loop Pedagogy and DA aimed to establish a caring and empowering ecosystem. Such an objective reflected the school culture and atmosphere which cultivated students’ well-being and confidence, as well as the harmonious relations among the community. At different phases of the Loop Pedagogy, students received scaffoldings and encouraging feedback from their teacher, tutors, and peers in the learning community. Unlike traditional writing instruction, which aims at improving students’ competence to produce linguistically accurate texts by themselves, ELC-based writing integrates instruction with DA and strives to nurture students’ ELC development to fulfil authentic tasks by participating in situation-embedded, action-oriented practice (e.g., writing/drawing), sharing among community (e.g., talking), and improving the practice (e.g., writing again according to feedback). As Winnie highlighted, “We were helping each other”. During the talk in Phase 2, Cathy and Crystal helped Eva translate the tutor’s questions, and the tutor provided Eva with guiding questions and encouraging affirmation. Such care and empowerment facilitated not only Eva’s meaning-making but also her value-realizing (Paul et al., 2023); as Eva reflected, the writing task was an “enjoyable and happy” process of “creating and imagining” which she found “meaningful” and “interesting”. In this sense, teaching writing through integrating the Loop Pedagogy and DA fostered ELC development through setting up situations for learning with (trans)languaging, mutual care, and self-value realization in a supportive community. As Anne’s metaphor summarizes, the Loop Pedagogy is thus “a good bonding time to know each other better”, and a pedagogy that helps students to “improve” their learning and makes them feel “satisfied” and “proud of” themselves.

6. Conclusions

The significance of this research is threefold. Theoretically, it proposed a theorization of the ELC notion and demonstrated a theoretical framework of the ELC-based integration of the Loop Pedagogy and DA for ELT writing. Pedagogically, it exemplified an implementation of the Loop Pedagogy as a dynamic synergy of assessment and instruction in a multilingual, multicultural, and inclusive classroom and provided frontline teachers with a theory-based model of ELC-based integration of assessment and instruction. Methodologically, it exemplified AI-facilitated data generation (e.g., Zoom-recorded auto-transcription of data) in research based on teacher–student interactions. However, it should be noted that the theoretical underpinning of ELC is abstract and complex, and the practice of ELC-based Loop Pedagogy remains rudimentary, which demands ongoing training for teachers. The ELC-based integration of the Loop Pedagogy and DA takes a longer time to administer than conventional static tests; therefore, careful adaptation is needed to enhance the feasibility and sustainability of the pedagogy. Further teacher-researcher collaborative action research and discussion are indispensable regarding the reliability and validity of ELC-based DA.

While traditional mindsets—such as the code-view of language, monolingualism, and test-driven pedagogy—remain dominant in many educational contexts, an ELC-based integration of pedagogy and assessment offers a paradigm-shifting lens for teachers to critically reflect on their ELT practices. This approach is crucial for implementing AI-assisted learning. Rather than reducing AI’s role to surface-level lexicogrammatical proofreading or translation (i.e., checking the use of language as codified knowledge points), an ELC-based pedagogy encourages students to engage with AI as a learning companion in the classroom—an affordance within the socio-ecological system that interacts with students through languaging and provides meaningful access and learning opportunities for higher-order inquiry, exploration, and creation.

Note: This article is a revised and expanded version of a paper entitled Exploring dynamic assessment in English Language Teaching: The Loop Pedagogy in inclusive classroom, which was presented at AsiaTefl2025 Conference, Hong Kong (SAR), China, 11 July 2025.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.H., P.J.T. and A.M.Y.L.; Methodology, P.H., P.J.T. and A.M.Y.L.; Validation, P.H., P.J.T., M.Z. and A.M.Y.L.; Formal analysis, P.H. and P.J.T.; Investigation, P.H., P.J.T., M.Z. and A.M.Y.L.; Resources, M.Z.; Data curation, P.H. and P.J.T.; Writing—original draft, P.H.; Writing—review & editing, P.H., P.J.T. and A.M.Y.L.; Supervision, A.M.Y.L.; Funding acquisition, A.M.Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Central Reserve Allocation Committee (CRAC), The Education University of Hong Kong, awarded to Prof. Angel M. Y. Lin (PI).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol code 2023-2024-0310 and date of 2024-02-27).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reasons).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alsaadi, H. M. A. (2021). Dynamic assessment in language learning; an overview and the impact of using social media. English Language Teaching, 14(8), 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., & Li, W. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism, and education. Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J. J. (1966). The senses considered as perceptual systems. Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- He, P., & Lin, A. M. Y. (2021). Translanguaging, trans-semiotizing, and trans-registering in a culturally and linguistically diverse science classroom. In A. Jakobsson, P. N. Larsson, & A. Karlsson (Eds.), Translanguaging in science education. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hymes, D. (1972). On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride, & J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics (pp. 269–293). Penguin. (Original work published 1964). [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, R., & Stewart, M. (2025). Embracing translanguaging in designing inclusive assessments with learners of English as an additional language or dialect. In J. P. Davies, S. Adams, C. Challen, & T. Bourke (Eds.), Designing inclusive assessment in schools: A guide to disciplinary and interdisciplinary practice (pp. 119–128). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lantolf, J. P., & Poehner, M. E. (2011). Dynamic assessment in the classroom: Vygotskian praxis for second language development. Language Teaching Research, 15(1), 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen-Freeman, D. (2015). Saying what we mean: Making the case for second language acquisition to become second language development. Language Teaching, 48, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen-Freeman, D. (2018). Looking ahead: Future directions in, and future research into, second language acquisition Diane. Foreign Language Annals, 51, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H., Ferreira, J. M., & Kuusisto, E. (2023). Dynamic assessment in inclusive elementary education: A systematic literature review of the usability, methods, and challenges in the past decade. European Journal of Special Education Research, 9(3), 94–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W. (2024). Transformative pedagogy for inclusion and social justice through translanguaging, co-learning, and transpositioning. Language Teaching, 57(2), 203–214. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W., & García, O. (2022). Not a first language but one repertoire: Translanguaging as a decolonizing project. RELC Journal, 53(2), 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A. M. Y. (2015). Egalitarian bi/multilingualism and trans-semiotizing in a global world. In W. E. Wright, S. Boun, & O. García (Eds.), Handbook of bilingual and multilingual education (pp. 19–37). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, A. M. Y., Wu, Y., & Lemke, J. L. (2020). “It takes a village to research a village”: Conversations with Jay Lemke on contemporary issues in translanguaging. In S. Lau, & S. Van Viegen Stille (Eds.), Critical plurilingual pedagogies: Struggling toward equity rather than equality. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, J., Nuesser, M., & Zheng, D. (2023). An ecological psychology perspective in teaching Chinese online. Journal of China Computer-Assisted Language Learning, 3(1), 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poehner, M. E. (2008). Dynamic assessment: A Vygotskian approach to understanding and promoting second language development. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Poehner, M. E., & Inbar-Lourie, O. (2020). Toward a reconceptualization of second language classroom assessment. Educational Linguistics, 41, 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Poehner, M. E., & Lantolf, J. P. (2005). Dynamic assessment in the language classroom. Language Teaching Research, 9(3), 233–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poehner, M. E., & Lantolf, J. P. (2024). Sociocultural theory and second language developmental education. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rashidi, N., & Bahadori Nejad, Z. (2018). An investigation into the effect of dynamic assessment on the EFL learners’ process writing development. SAGE Open, 8(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schissel, J. L., De Korne, H., & López-Gopar, M. (2021). Grappling with translanguaging for teaching and assessment in culturally and linguistically diverse contexts: Teacher perspectives from Oaxaca, Mexico. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(3), 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohamy, E. (2011). Assessing multilingual competencies: Adopting construct valid assessment policies. The Modern Language Journal, 95(3), 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TESOL For All. (2025, February 19). What is languaging? An interview with professor paul thibault [video]. YouTube. Available online: https://youtu.be/YfYdMN3HI6o?si=MRl5n9QNMVQ0qNnj (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- The New Territories Group. (forthcoming). Ecological languaging competences (ELC): Teaching, learning and assessment. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thibault, P. J. (2011). First-order languaging dynamics and second-order language: The distributed language view. Ecological Psychology, 23(3), 210–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibault, P. J. (2021). Languaging: Distributed language, affective dynamics, and the human ecology. Vol. I. the sense-making body. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thibault, P. J. (2024). The loop pedagogy. Unpublished document. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Available online: https://docs.un.org/en/A/RES/70/1 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- van Lier, L. (2000). From input to affordance: Social-interactive learning from an ecological perspective. In J. P. Lantolf (Ed.), Sociocultural theory and second language learning: Recent advances (pp. 245–259). OUP. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y., & Qian, D. D. (2023). Enhancing EFL learners’ reading proficiency through dynamic assessment. Language Assessment Quarterly, 20(1), 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M. F. (2004). An ecological psychology of instructional design: Learning and thinking by perceiving acting systems. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 169–177). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D. (2012). Caring in the dynamics of design and languaging: Exploring second language learning in virtual spaces. Language Sciences, 34, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.