Fostering a Synergy Between the Development of Well-Being and Musicianship: A Kinemusical Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

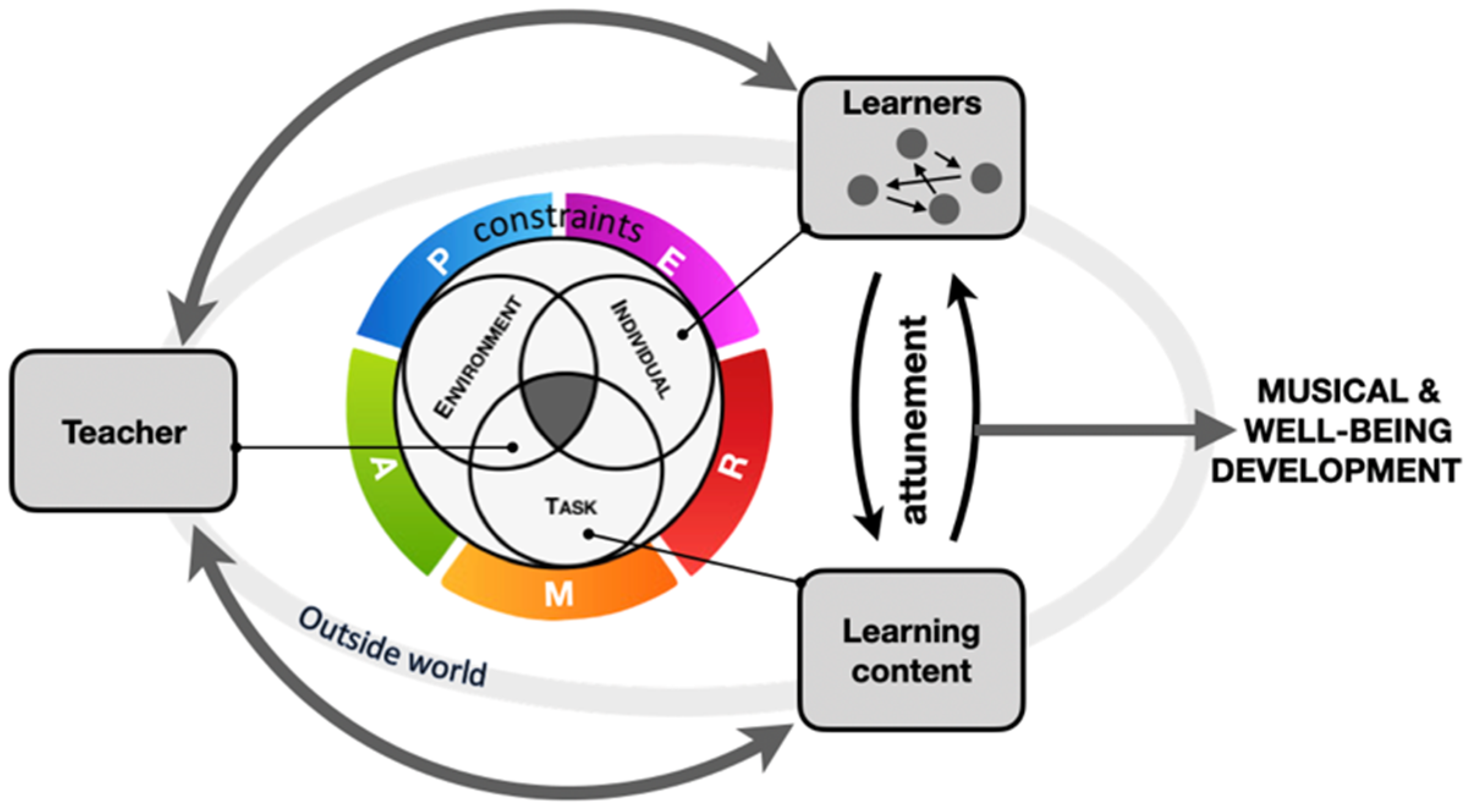

2. Towards a ‘Caring’ Music School: Defining the DNA of Music Education

3. Creating a Synergy: The Didactic Integration of the PERMA Building Blocks of Well-Being

4. A Kinemusical Approach to Instrumental Music Education

4.1. Developing the Inner Musician

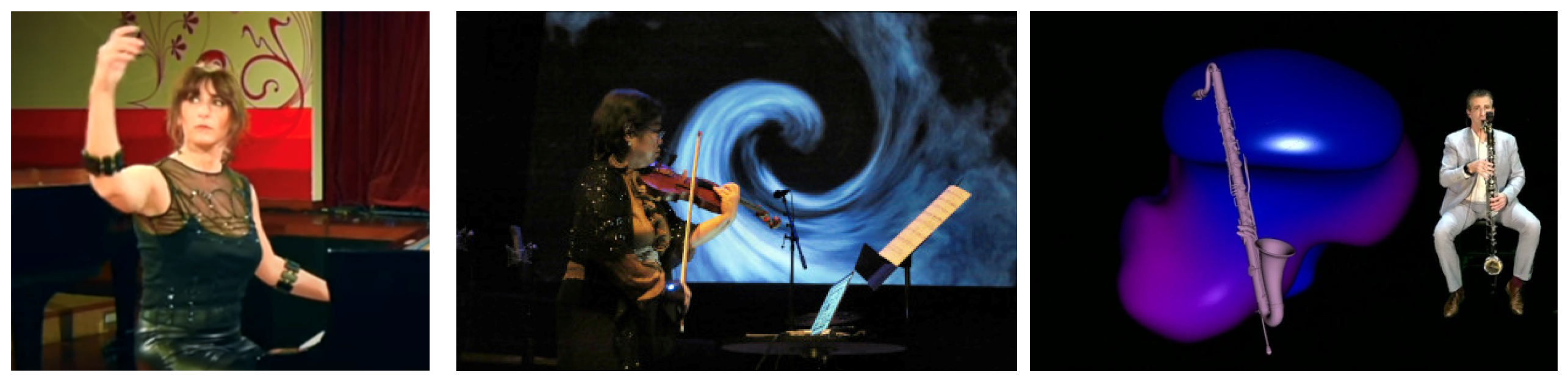

4.2. Moving While Playing the Instrument

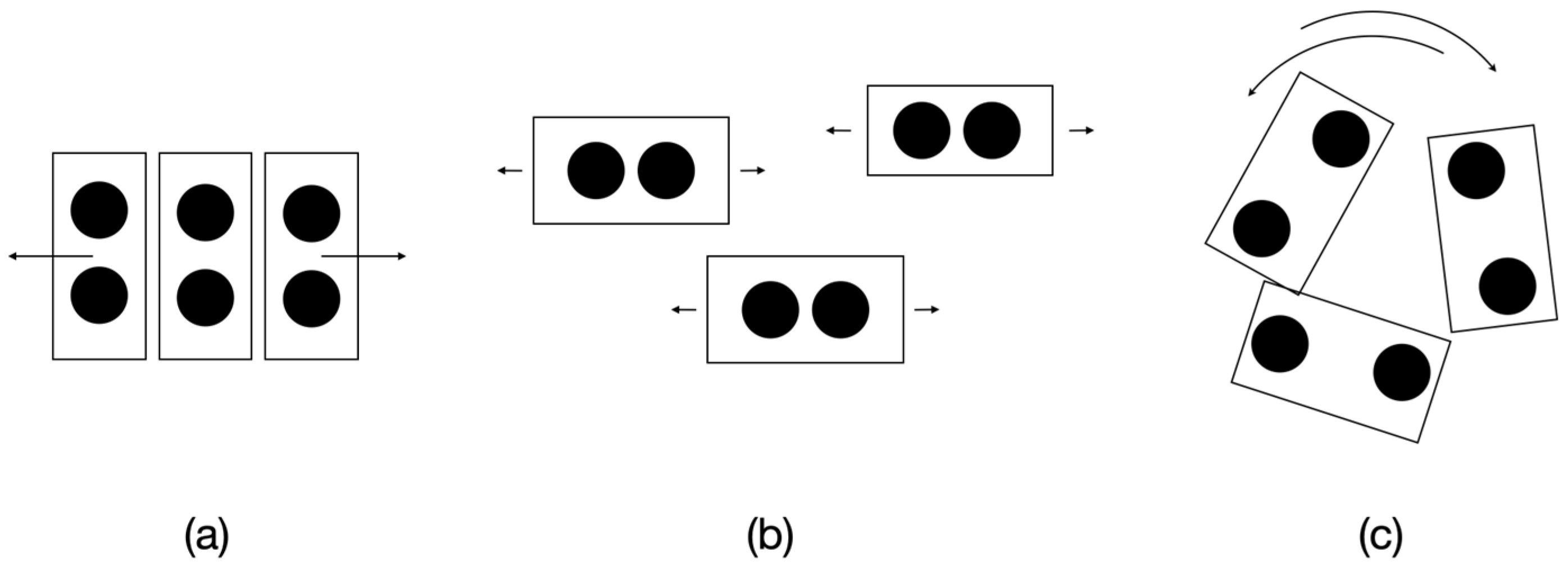

4.3. Bottom-Up Approach

4.4. From Simple to Complex

4.5. Preparing the Performing Body

5. Creating the Synergy Between Well-Being and Musical Development Through the Integration of Movement in the Instrumental Learning Process

- “Meet ‘n greet”

- Step ‘n play

6. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ackermann, B., Adams, R., & Marshall, E. (2002). Strength or endurance training for undergraduate music majors at a university? Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 17(1), 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, E., Rose, D., & Wasley, D. (2020). Health and wellbeing in higher education: A comparison of music and sport students through the framework of self determination theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 566307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allsup, R. E., & Benedict, C. (2008). The problems of band: An inquiry into the future of instrumental music education. Philosophy of Music Education Review, 16(2), 156–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, L., Lã, F. M., & Silva, A. G. (2016). Pain and posture of children and adolescents who learn the accordion as compared with non-musician students. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 31(4), 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audiffren, M., & André, N. (2014). The strength model of self-control revisited: Linking acute and chronic effects of exercise on executive functions. Journal of Sports and Health Science, 4(1), 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baadjou, V. A. E. (2018). Musculoskeletal complaints in musicians: Epidemiology, phenomenology, and prevention [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Maastricht University]. [Google Scholar]

- Baadjou, V. A. E., Roussel, N. A., Verbunt, J. A., Smeets, R. J., & de Bie, R. A. (2016). Systematic review: Risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders in musicians. Occupational Medicine, 66(8), 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartos, L. J., Funes, M. J., Ouellet, M., Pilar Posadas, M., Immink, M. A., & Krägeloh, C. (2022). A feasibility study of a program integrating mindfulness, yoga, positive psychology, and emotional intelligence in tertiary-level student musicians. Mindfulness, 13(10), 2507–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C., Rast, F., Ernst, M. J., Meichtry, A., Kool, J., Rissanen, S. M., & Kankaanpää, M. (2017). The effect of muscle fatigue and low back pain on lumbar movement variability and complexity. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, 33, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, E. (1989). At the service of the sonata: Music lessons with merleau-ponty. In H. Pietersam (Ed.), Merleau-ponty: Critical essays (pp. 23–29). University Press of America/Center for Advanced Research in Phenomenology. [Google Scholar]

- Behrends, A., Muller, S., & Dziobek, I. (2012). Moving in and out of synchrony: A concept of a new intervention fostering empathy through interactional movement and dance. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39(2), 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, H. C., II. (2023). Helping music education majors through positive psychology: A review of the literature. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 24(si2.4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, N. (1967). The co-ordination and regulation of movements. Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bonneville-Roussy, A., Hruska, E., & Trower, H. (2020). Teaching music to support students: How autonomy-supportive music teachers increase students’ well-being. Journal of Research in Music Education, 68(1), 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgo, D. (2022). Sync or swarm. Improvising music in a complex age. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, W. D. (2000). A somatic, “here and now” semantic: Music, body, and self. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 144, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bowman, W. D. (2004). Cognition and the body: Perspectives from music education. In L. Bressler (Ed.), Knowing bodies, moving minds: Towards embodied teaching and learning (pp. 29–50). Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, K. K. (2008). Rudolf laban. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bragge, P., Bialocerkowski, A., & McMeeken, J. (2006). A systematic review of prevalence and risk factors associated with playing-related musculoskeletal disorders in pianists. Occupational Medicine, 56(1), 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandler, B. J., & Peynircioglu, Z. F. (2015). A comparison of the efficacy of individual and collaborative music learning in ensemble rehearsals. Journal of Research in Music Education, 63(3), 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun Janzen, T., Thompson, W. F., Ammirante, P., & Ranvaud, R. (2014). Timing skills and expertise: Discrete and continuous timed movements among musicians and athletes. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, e1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremmer, M., & Nijs, L. (2020). The Role of the Body in Instrumental and Vocal Music Pedagogy: A Dynamical Systems Theory Perspective on the Music Teacher’s Bodily Engagement in Teaching and Learning. Frontiers in Education, 5, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremmer, M., & Nijs, L. (2022). Embodied Music Pedagogy. A vision on the dynamic role of the body in music education. In T. Buchborn, S. Schmid, G. Brunner, & T. De Baets (Eds.), European perspectives on music education: Music Is What People Do (pp. 29–46). Helbling. [Google Scholar]

- Bremmer, M., & Nijs, L. (2024). Embodiment in music education. Journal de recherche en éducations artistiques, 2, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buecker, S., Simacek, T., Ingwersen, B., Terwiel, S., & Simonsmeier, B. A. (2020). Physical activity and subjective well-being in healthy individuals: A meta-analytic review. Health Psychology Review, 15(4), 574–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, A. L. (2019). Class, control, and classical music. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, A. L. (2021). Power relations and hierarchies in higher music education institutions. Research Report. The University of York. [Google Scholar]

- Bundick, M. J. (2011). Extracurricular activities, positive youth development, and the role of meaningfulness of engagement. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(1), 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnard, P., & Dragovic, T. (2015). Collaborative creativity in instrumental group music learning as a site for enhancing pupil wellbeing. Cambridge Journal of Education, 45(3), 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burwell, K. (2012). Studio-based instrumental learning. Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Burwell, K. (2020). Authoritative discourse in advanced studio lessons. Advance online publication. Musicae Scientiae, 25(4), 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burwell, K., Carey, G., & Bennett, D. (2019). Isolation in studio music teaching: The secret garden. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 18(4), 372–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burzik, A. (2003). Go with the flow. Strad, 114(1359), 714–718. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J., & Kern, M. L. (2015). The PERMA-profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 6(3), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, K., Hyodo, K., Suwabe, K., Ochi, G., Sakairi, Y., Kato, M., Dan, I., & Soya, H. (2014). Positive effect of acute mild exercise on executive function via arousal-related prefrontal activations: An fNBIRS study. NeuroImage, 41(1), 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cara, M. A., Lobos, C., Varas, M., & Torres, O. (2022). Understanding the association between musical sophistication and well-being in music students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, F., & González, M. (2017). School: One world or two worlds? Children’s perspectives. Children and Youth Services Review, 80, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., Rolf, T. W., & Michael, S. N. (1999). Optimal experience of web activities. Computers in Human Behavior, 15(5), 585–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, J. H., Molani, Z., Sadhukha, S., & Chang, L. J. (2023). Synchronized affect in shared experiences strengthens social connection. Communications Biology, 6, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, J. C. (2023). A case report on the impact of feldenkrais method® with experienced pianists. Feldenkrais Research Journal, 7. Available online: https://feldenkraisresearchjournal.org/index.php/journal/article/view/135 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Chirico, A., Serino, S., Cipresso, P., Gaggioli, A., & Riva, G. (2015). When music “flows”. State and trait in musical performance, composition and listening: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J. Y. (2013). Nonlinear learning underpinning pedagogy: Evidence, challenges, and implications. Quest, 65(4), 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, E. F. (2014). Lost and found in music: Music, consciousness and subjectivity. Musicae Scientiae, 18(3), 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, M., Sager, R., & Will, U. (2005). In time with the music: The concept of entrainment and its significance for ethnomusicology. ESEM Counterpoint, 11, 3–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (2006). Social, emotional, ethical, and academic education: Creating a climate for learning, participation in democracy, and well-being. Harvard Educational Review, 76, 201–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colley, I., Varlet, M., MacRitchie, J., & Keller, P. E. (2020). The influence of a conductor and co-performer on auditory-motor synchronisation, temporal prediction, and ancillary entrainment in a musical drumming task. Human Movement Science, 72, 102653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croom, A. M. (2015). Music practice and participation for psychological well-being: A review of how music influences positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment. Musicae Scientiae, 19, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, I. (2007). Music and cognitive evolution. In R. I. M. Dunbar, & L. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of evolutionary psychology (pp. 649–667). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, S., & Huron, D. (2007, August 27–31). The influence of body morphology on preferred dance tempos. 2007 International Computer Music Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, J. W., & Brighton, M. C. (2009). Bodily mediated coordination, collaboration, and communication in music performance. In S. Hallam, I. Cross, & M. H. Thaut (Eds.), Oxford handbook of music psychology (pp. 573–595). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, J. (2020). Alexander Technique classes improve pain and performance factors in tertiary music students. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 24(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M. J., & Davies, R. S. (2018, November 19–21). Beyond below-ground geological complexity: Developing adaptive expertise in exploration decision-making. Complex Orebodies Conference, Brisbane, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- De Jaegher, H., & Di Paolo, E. (2007). Participatory sense-making: An enactive approach to social cognition. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 6(4), 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleuze, G. (1968). Différence et répétition. Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Demirbatir, E., Helvaci, A., Yilmaz, N., Gul, G., Senol, A., & Bilgel, N. (2013). The psychological well-being, happiness and life satisfaction of music students. Psychology, 4(11), 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, G. S. (2021). Body mapping: An approach to understand and reduce common injuries in musicians. Canadian Winds: The Journal of the Canadian Band Association, 19(2), 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Faran, M., Akram, S., Tahir, N., & Malik, F. (2021). Uses of music and flourish: Mediating role of emotion regulation in university students. Journal of Behavioural Sciences, 31(2), 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, S. B., White, G. W., Balcazar, F. E., Suarez-Balcazar, Y. R., Mathews, M., Paine-Andrews, A., Seekins, T., & Smith, J. F. (1994). A contextual-behavioral model of empowerment: Case studies involving people with physical disabilities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 22(4), 471–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, S., & Nijs, L. (2019). Children’s representational strategies based on verbal versus bodily interactions with music: An intervention-based study. Music Education Research, 22(1), 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, S., & Nijs, L. (2020). Children’s verbal explanations of their visual representation of the music. International Journal of Music Education, 38(4), 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, S., & Nijs, L. (2022). The influence of discrete versus continuous movements on children’s musical sense-making. British Journal of Music Education, 39(2), 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, T. D., Michelbrink, M., Beckmann, M., & Schöllhorn, W. I. (2008). A quantitative dynamical systems approach to differential learning: Self-organization principle and order parameter equations. Biological Cybernetics, 98(1), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederickson, K. B. (2002). Fit to play: Musicians’ health tips. Music Educators Journal, 88(6), 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, T., & De Jaegher, H. (2009). Enactive intersubjectivity: Participatory sense-making and mutual incorporation. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 8, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, K., Kimura, M., & Daibo, I. (2020). Rhythmic features of movement synchrony for bonding individuals in dyadic interaction. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 44(1), 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunt, H. (2005). Instrumental/vocal teaching and learning in conservatoires: A case study of teachers’ perceptions. In G. Odam, & N. Bannan (Eds.), The reflective conservatoire. Studies in music education (pp. 249–274). Guildhall School of Music and Drama. [Google Scholar]

- Gaunt, H. (2008). One-to-one tuition in a conservatoire: The perceptions of instrumental and vocal teachers. Psychology of Music, 36(2), 215–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Gipson, C. L., Gorman, J. C., & Hessler, E. E. (2016). Top-down (prior knowledge) and bottom-up (perceptual modality) influences on spontaneous interpersonal synchronization. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 20(2), 193–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, E. E. (2003). Learning sequence in music: Skill, content, and patterns. GIA Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, E. E. (2007). Learning sequences in music: A contemporary music learning theory. GIA Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Goubault, E., Turner, C., Mailly, R., Begon, M., Dal Maso, F., & Verdugo, F. (2023). Endurance capacities of expert pianists: An electromyographic and kinematic variability study. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-2544271/v1 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Goubault, E., Verdugo, F., Pelletier, J., Traube, C., Begon, M., & Dal Maso, F. (2021). Exhausting repetitive piano tasks lead to local forearm manifestation of muscle fatigue and negatively affect musical parameters. Scientific Reports, 11, 8117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhead, K. (2016). Becoming music: Reflections on transformative experience and the development of agency through dynamic rehearsal. Arts and Humanities as Higher Education, 15(3). Available online: http://www.artsandhumanities.org/journal/becoming-music-reflections-on-transformative-experience-and-the-development-of-agency-through-dynamic-rehearsal/ (accessed on 15 September 2015).

- Gupta, R. (2019). Positive emotions have a unique capacity to capture attention. Progress in Brain Research, 247, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habe, K., & Biasutti, M. (2023). Flow in Music Performance: From Theory to Educational Applications. Psihologijske Teme, 32(1), 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanken, I. M. (2004). The fears and joys of new forms of investigation into teaching: Student evaluation of instrumental teaching. In J. Davidson (Ed.), The music practitioner (pp. 285–294). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hanken, I. M. (2016). Peer learning in specialist higher music education. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 15(3–4), 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härkki, T., Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P., Vartiainen, H., Saarinen, A., & Hakkarainen, K. (2023). Non-linear maker pedagogy in Finnish craft education. Techne Serien-Forskning i Slöjdpedagogik och Slöjdvetenskap, 30(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, K. (2018). Compassionate music teaching: A framework for motivation and engagement in the 21st century. Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, T. (2012). Constraints-led approach and emergent learning: Using complexity thinking to frame collectives in creative dance and inventing games as learning systems. The Open Sports Sciences Journal, 5(1), 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, E. M., Ropar, D., Newport, R., & Tunçgenç, B. (2021). Social context facilitates visuomotor synchrony and bonding in children and adults. Scientific Reports, 11, 22869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E. S., Hills, K., Jiang, X., Long, R., Kelly, R., & Lyons, M. (2014). Schooling and children’s subjective well-being. In A. Ben-Arieh, F. Casas, I. Frønes, & J. E. Korbin (Eds.), Handbook of child well-being (pp. 797–819). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Jääskeläinen, T. (2022). “Music is my life”: Examining the connections between music students’ workload experiences in higher education and meaningful engagement in music. Research Studies in Music Education, 45(2), 260–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jääskeläinen, T., López-Íñiguez, G., & Phillips, M. (2020). Music students’ experienced workload, livelihoods and stress in higher education in Finland and the United Kingdom. Music Education Research, 22(5), 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janata, P., Tomic, S. T., & Haberman, J. M. (2012). Sensorimotor coupling in music and the psychology of the groove. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(1), 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensenius, A. R., Wanderley, M., Godoy, R., & Leman, M. (2010). Musical gestures: Concepts and methods in research. In R. I. Godoy, & M. Leman (Eds.), Music, gesture, and the formation of embodied meaning (pp. 12–35). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Juntunen, M. L., & Westerlund, H. (2001). Digging dalcroze, or, dissolving the mind–body dualism: Philosophical and practical remarks on the musical body in action. Music Education Research, 3(2), 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegelaers, J., Schuijer, M., & Oudejans, R. D. (2021). Resilience and mental health issues in classical musicians: A preliminary study. Psychology of Music, 49(5), 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D., & Ackermann, B. (2015). Performance-related musculoskeletal pain, depression and music performance anxiety in professional orchestral musicians: A population study. Psychology of Music, 43(1), 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M. L., Allen, K. A., Furlong, M., Vella-Brodrick, S., & Suldo, S. (2021). PERMAH: A useful model for focusing on wellbeing in schools. In M. J. Furlong, R. Gilman, & E. S. Huebner (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology in schools (pp. 12–24). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel, M., Hristova, D., & Kussmaul, K. (2018). Sources of embodied creativity: Interactivity and ideation in contact improvisation. Behavioral Sciences, 8(6), 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjølberg, K. (2015, 26 February–1 March). Vocal pedagogy students’ artistic identity development through peer learning. Symposium ‘Peer Learning in Music Academies’, The Reflective Conservatoire Conference GSMD, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Konczak, J., Vander Velden, H., & Jaeger, L. (2009). Learning to play the violin: Motor control by freezing, not freeing degrees of freedom. Journal of Motor Behavior, 41(3), 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koops, L. H., & Kuebel, C. R. (2021). Self-reported mental health and mental illness among university music students in the United States. Research Studies in Music Education, 43(2), 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamont, A., & Ranaweera, N. A. (2020). Knit one, play one: Comparing the effects of amateur knitting and amateur music participation on happiness and wellbeing. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(5), 1353–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Krause, A. E., & Davidson, J. W. (2017). The PERMA well-being model and music facilitation practice: Preliminary documentation for well-being through music provision in Australian schools. Research Studies in Music Education, 39(1), 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leman, M. (2007). Embodied music cognition and mediation technology. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leman, M. (2016). The expressive moment: How interaction (with music) shapes human empowerment. The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lesaffre, M., & Leman, M. (2020). Integrative research in art and science: A framework for proactive humanities. Critical Arts, 34(5), 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M., Creech, A., Gaunt, H., & Hallam, S. (2014). Conservatoire students’ experiences and perceptions of instrument-specific master classes. Music Education Research, 16(2), 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łucznik, K., & May, J. (2021). Measuring individual and group flow in collaborative improvisational dance. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 40, 100847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, R. A. (2013). Music, health, and well-being: A review. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 8(1), 20635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manifold, L. H. (2008). Applying Jaques-Dalcroze’s method to teaching musical instruments and its effect on the learning process. Available online: https://manifoldmelodies.com/docs/Manifold_Dalcroze_voice.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Martin Lopez, T., & Farias Martınez, J. (2013). Strategies to promote health and prevent musculoskeletal injuries in students from the High Conservatory of Music of Salamanca. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 28(2), 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C. (2024). Expressive movements in piano performance: The inducing factors. Journal of Human Movement Science, 5(1), 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V. (2019). Creating the third teacher through participatory learning environment design: Reggio emilia principles support student wellbeing. In H. Hughes, J. Franz, & J. Willis (Eds.), School spaces for student wellbeing and learning (pp. 239–258). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Moberg, N., & Georgii-Hemming, E. (2019). Musicianship: Discursive constructions of autonomy and independence within music performance programmes. In S. Gies, & J. H. Sætre (Eds.), Becoming musicians—Student involvement and teacher collaboration in higher music education (pp. 67–88). The Norwegian Academy of Music. [Google Scholar]

- Mogan, R., Fischer, R., & Bulbulia, J. A. (2017). To be in synchrony or not? A meta-analysis of synchrony’s effects on behavior, perception, cognition and affect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 72, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, I. (2015). Teaching happiness and well-being in schools: Learning to ride elephants. Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). The concept of flow. In C. R. Snyder, & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 89–105). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, K. M. (2003). Change in motor learning: A coordination and control perspective. Motriz Rio Claro, 9(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Newland, I. (2014). Instrumental gesture as choreographic practice: Performative approaches to understanding corporeal expressivity in music. Choreographic Practices, 5(2), 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijs, L. (2017). The merging of musician and musical instrument: Incorporation, presence and the levels of embodiment. In M. Lesaffre, P. J. Maes, & M. Leman (Eds.), The routledge companion to embodied music interaction (pp. 49–57). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nijs, L. (2019). Moving together while playing music: Promoting involvement through student-centred collaborative practices. In S. Gies, & J. H. Sætre (Eds.), Becoming musicians–student involvement and teacher collaboration in higher music education (pp. 239–260). The Norwegian Academy of Music. [Google Scholar]

- Nijs, L., Grinspun, N., & Fortuna, S. (2024). Creativity through movement: Navigating the musical affordance space. Creativity Research Journal, 7(3), 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, L., Lesaffre, M., & Leman, M. (2013). The Musical Instrument as a Natural Extension of the Musician. In M. Castellengo, & H. Genevois (Eds.), Music and its instruments (pp. 467–484). Editions Delatour France. [Google Scholar]

- Nijs, L., Moens, B., Lesaffre, M., & Leman, M. (2012). The Music Paint Machine: Stimulating self-monitoring through the generation of creative visual output using a technology-enhanced learning tool. Journal of New Music Research, 41(1), 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijs, L., & Nicolaou, G. (2021). Flourishing in resonance: Joint resilience building through music and motion. Frontiers in psychology, research topic on eudaimonia and music learning, 12, 666702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offermans, W. (1992). For the contemporary flutist: 12 Studies on contemporary flute techniques. Zimmermann. [Google Scholar]

- Oswald, P. F. (1992). Psychodynamics of musicians: The relationship of performers to their musical instruments. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 7(4), 110–113. [Google Scholar]

- Pacherie, E. (2014). How does it feel to act together? Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 13(1), 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, T. J. (2015). The positive pianist: How flow can bring passion to practice and performance. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patston, T., & Waters, L. (2015). Positive instruction in music studios: Introducing a new model for teaching studio music in schools based upon positive psychology. Psychology of Well-Being, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pels, F., Kleinert, J., & Mennigen, F. (2018). Group flow: A scoping review of definitions, theoretical approaches, measures and findings. PLoS ONE, 13(12), e0210117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips-Silver, J., & Keller, P. E. (2012). Searching for roots of entrainment and joint action in early musical interactions. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Presland, C. (2005). Conservatoire student and instrumental professor: The student perspective on a complex relationship. British Journal of Music Education, 22(3), 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, I., & Chow, J. Y. (2019). A constraint-led approach to sport and physical education pedagogy. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(2), 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reybrouck, M., & Eerola, T. (2022). Musical enjoyment and reward: From hedonic pleasure to eudaimonic listening. Behavioral Sciences, 12(5), 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, K. (2006). Foundations for flow: A philosophical model for studio instruction. Philosophy of Music Education Review, 14(2), 175–191. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40327253 (accessed on 15 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Riva, G., & Gaggioli, A. (2015). Positive change and positive technology. In P. Inghilleri, G. Riva, & E. Riva (Eds.), Enabling positive change: Flow and complexity in daily experience (pp. 39–49). De Gruyter Open. [Google Scholar]

- Roda, A., Canazza, S., & De Poli, G. (2014). Clustering affective qualities of classical music: Beyond the valence-arousal plane. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 5(4), 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roden, I., Kreutz, G., & Bongard, S. (2012). Effects of a school- based instrumental music program on verbal and visual memory in primary school children: A longitudinal study. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 3, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royea, D. A., & Nicol, C. (2019). Pre-service teachers’ experiences of learning study: Learning with and using variation theory. Educational Action Research, 27(4), 564–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J. A., & Benedetto, R. L. (2014). Perceived musculoskeletal discomfort among elementary, middle, and high school string players. Journal of Research in Music Education, 62(3), 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, P. E., Loui, P., Tarr, B., Schachner, A., Glowacki, L., Mithen, S., & Fitch, W. T. (2021). Music as a coevolved system for social bonding. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 44, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelsbergh, G. J. P., Kamper, W. J., Rabius, J., De Koning, J. J., & Schöllhorn, W. I. (2010). A new method to learn to start in speed skating: A differencial learning approach. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 41(4), 415. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, K. (2015). Group flow and group genius. NAMTA Journal, 40(3), 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Schiavio, A., & De Jaegher, H. (2017). Participatory sense-making in joint musical practices. In M. Lesaffre, P. J. Maes, & M. Leman (Eds.), The Routledge companion to embodied music interaction (pp. 31–39). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Schiavio, A., & Van der Schyff, D. (2018). 4E music pedagogy and the principles of self-organization. Behavioural Sciences, 8, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavio, A., Van der Schyff, D., Biasutti, M., Moran, N., & Parncutt, R. (2019). Instrumental technique, expressivity, and communication. A qualitative study on learning music in individual and collective settings. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R. A. (1975). A schema theory of discrete motor skill learning. Psychological Review, 82(4), 225–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnebly-Black, J., & Moore, S. F. (2004). Rhythm: One on one: Dalcroze activities in the private music lesson. Alfred Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Schöllhorn, W. I. (2000). Applications of systems dynamic principles to technique and strength training. Acta Academiae Olympiquae Estoniae, 8, 67–85. [Google Scholar]

- Schöllhorn, W. I., Hegen, P., & Davids, K. (2012). The nonlinear nature of learning—A differential learning approach. The Open Sport Science Journal, 5, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2003). Self-regulation and learning. In I. B. Weiner, W. M. Reynolds, & G. E. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Educational psychology (pp. 45–46). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education, 35(3), 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafir, T., Taylor, A. S. F., Atkinson, A. P., Langenecker, S. A., & Zubieta, J. K. (2013). Emotion regulation through execution, observation, and imagery of emotional movements. Brain and Cognition, 82(2), 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheets-Johnstone, M. (2010). Body and movement: Basic dynamic principles. In S. Gallagher, & D. Schmicking (Eds.), Handbook of phenomenology and cognitive science (pp. 217–234). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sheets-Johnstone, M. (2011). The primacy of movement. John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh Asadi, F., & Hojat, S. (2020). Investigation of place components affecting the child’s perception of the school environment utilizing Q-sort methodology. Iran University of Science & Technology, 30(2), 184–197. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, J. (2002). How music works. Beyond the immanent and the arbitrary: An essay review of music in everyday life. Action, Criticism, and Theory for Music Education, 1(2), 2–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, A., & Broughton, M. C. (2020). Promoting wellbeing and health through active participation in music and dance: A systematic review. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 15(1), 1732526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M. (2020). Sense-making, meaningfulness and instrumental music education. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, M. (2023). Caring about caring for music education. In K. S. Hendricks (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of care in music education (pp. 31–43). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Simoens, V. L., & Tervaniemi, M. (2013). Musician–instrument relationship as a candidate index for professional well-being in musicians. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 7(2), 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slepian, M. L., & Ambady, N. (2012). Fluid movement and creativity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(4), 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. D., & Silverman, M. (Eds.). (2020). Eudaimonia: Perspectives for music learning. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Smykovskyi, A., Bieńkiewicz, M., Pla, S., Janaqi, S., & Bardy, B. G. (2022). Positive emotions foster spontaneous synchronisation in a group movement improvisation task. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 16, 944241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanhope, J., Pisaniello, D., & Weinstein, P. (2022). The effect of strategies to prevent and manage musicians’ musculoskeletal symptoms: A systematic review. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health, 77(3), 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steemers, S., van Rijn, R. M., van Middelkoop, M., Bierma-Zeinstra, S., & Stubbe, J. H. (2020). Health problems in conservatoire students: A retrospective study focusing on playing-related musculoskeletal disorders and mental health. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 35(4), 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupacher, J. (2019). The experience of flow during sensorimotor synchronization to musical rhythms. Musicae Scientiae, 23(3), 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teune, B., Woods, C., Sweeting, A., Inness, M., & Robertson, S. (2022). The influence of individual, task, and environmental constraint interaction on skilled behaviour in Australian Football training. Journal of Sports Sciences, 40(17), 1991–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmers, R., Bailes, F., & Daffern, H. (2021). Together in music: Coordination, expression, participation. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torrents, C., Balagué, N., Ric, A., & Hristovski, R. (2021). The motor creativity paradox: Constraining to release degrees of freedom. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 15(2), 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschacher, W., Rees, G. M., & Ramseyer, F. (2014). Nonverbal synchrony and affect in dyadic interactions. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuitert, I., Bootsma, R. J., Schoemaker, M. M., Otten, E., Mouton, L. J., & Bongers, R. M. (2017). Does practicing a wide range of joint angle configurations lead to higher flexibility in a manual obstacle-avoidance target-pointing task? PLoS ONE, 12(7), e0181041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, C., Goubault, E., Dal Maso, F., Begon, M., & Verdugo, F. (2023). The influence of proximal motor strategies on pianists’ upper-limb movement variability. Human Movement Science, 90, 103110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaag, J., Bjørngaard, J. H., & Bjerkeset, O. (2016). Use of psychotherapy and psychotropic medication among Norwegian musicians compared to the general workforce. Psychology of Music, 44(6), 1439–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Elst, O. F., Vuust, P., & Kringelbach, M. L. (2021). Sweet anticipation and positive emotions in music, groove, and dance. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 39, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Merwe, L. (2023). Meaningful instrumental music education: Teaching for well-being. The South African Music Teacher, 156, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Varvarigou, M. (2017). Promoting collaborative playful experimentation through group playing by ear in higher education. Research Studies in Music Education, 39(2), 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella-Brodrick, D., Frisina, J., Chin, T. C., & Joshanloo, M. (2022). Tracking the effects of positive education around the world. In M. J. Furlong, R. Gilman, & E. S. Huebner (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology in schools (pp. 437–450). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, A., Lee, M., Barringham, T., & Salehi, N. (2022). Out of tune: Perceptions of, engagement with, and responses to mental health interventions by professional popular musicians—A scoping review. Psychology of Music, 50(3), 814–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedin, E. (2015). Playing music with the whole body. Eurhythmics and motor development. Germans Musicförlag AB. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, G. F., Biasutti, M., MacRitchie, J., McPherson, G. E., & Himonides, E. (2020). The impact of music on human development and well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westervelt, T. G. (2002). Beginning continuous fluid motion in the music classroom. General Music Today, 15(3), 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickström, D. E. (2023). Inside looking in. In A. Bull, C. Scharff, & L. Nooshin (Eds.), Voices for change in the classical music profession: New ideas for tackling inequalities and exclusions (pp. 54–66). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, C., Priebus, J., Biallas, B., & Froböse, I. (2011). Motor activity as a way of preventing musculoskeletal problems in string musicians. Medical Problems of Performing Artists, 26(1), 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamon, A. (2004). Musical excellence: Strategies and techniques to enhance performance. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wristen, B. G. (2013). Depression and anxiety in university music students. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 31(2), 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y. (2020). Application of positive psychology in classroom teaching of vocal music. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 29(1), 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhukov, K. (2015). Challenging approaches to assessment of instrumental learning. In D. Lebler, G. Carey, & S. D. Harrison (Eds.), Assessment in music education: From policy to practice (pp. 55–70). Springer. [Google Scholar]

| Type | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Exploratory | Free movements to discover movements that fit the music and are possible with the instrument | Turning or bending the torso, walk freely around |

| Complementary | Movements that add something to the musical focus (e.g., meter) or facilitate an aspect of playing (e.g., feel the beat) | Perform a stepping pattern (e.g., right foot aside, join left foot, left foot aside, join right foot, repeat), walk to the beat |

| Aligning | Movements that follow a certain element in the music (e.g., the melody) | Turn the body from left to right to bodily express the length of a phrase |

| Preparing | Movements that prepare a certain musical task | Loosen the joints by exploring the degrees of freedom in a joint while playing a note, a rhythm…, exercise a certain stepping pattern prior to playing |

| Independent | Movements that are decoupled from the music | Swing a leg while playing a difficult passage |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nijs, L. Fostering a Synergy Between the Development of Well-Being and Musicianship: A Kinemusical Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1245. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091245

Nijs L. Fostering a Synergy Between the Development of Well-Being and Musicianship: A Kinemusical Perspective. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1245. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091245

Chicago/Turabian StyleNijs, Luc. 2025. "Fostering a Synergy Between the Development of Well-Being and Musicianship: A Kinemusical Perspective" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1245. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091245

APA StyleNijs, L. (2025). Fostering a Synergy Between the Development of Well-Being and Musicianship: A Kinemusical Perspective. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1245. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091245