Abstract

This study investigates the causes of mathematics anxiety, its effect on mathematical performance, and the influence of field placement among preservice teachers enrolled in a field-based elementary mathematics methods course. To investigate this, the study utilized four tools: the Abbreviated Mathematics Anxiety Rating Scale (A-MARS), concept maps, Praxis Core test score, and questionnaires. The quantitative analysis indicates a negative correlation between anxiety and math performance. The analysis of concept maps and questionnaires indicate that key contributors to math anxiety include pop-up quizzes, tests, exams, memorization of mathematical ideas, and past negative experiences with school mathematics. The qualitative data analysis revealed that reduced mathematics anxiety during field placements was primarily due to practical teaching experience, constructive feedback, positive student interactions, and opportunities for observation and reflection. Understanding the root causes of mathematics anxiety is essential for supporting preservice teachers and improving their teaching effectiveness. Additionally, field placements play a crucial role in reducing math anxiety by providing hands-on teaching experience and building confidence. It is important to alleviate math anxiety in preservice teachers to have a more positive impact on their future students.

1. Introduction

Over the last five decades, mathematics anxiety has emerged as a significant focus of research within the mathematics education community. Given its harmful impact on the teaching and learning of mathematics, researchers have worked to uncover its root causes, manifestations, and implications for both teachers and students. Spielberger (1972) describes anxiety as a state, a trait, and a process, emphasizing how it develops over time through exposure to stressors, perceived threats, reprisals, and coping mechanisms. Cemen (1987) offers a specific definition of mathematics anxiety, describing it as a state of discomfort arising from mathematics-related situations perceived as threatening to one’s self-esteem. This definition captures the emotional, cognitive, and psychological dimensions of mathematics anxiety, highlighting its potential to evoke feelings of panic, tension, helplessness, fear, distress, shame, and difficulty concentrating on mathematics tasks. Suárez-Pellicioni et al. (2016) further state that mathematics anxiety is a situation caused by mathematical activities that evoke an emotional response, disturbing an individual’s performance. By disrupting cognitive processes, affecting emotional well-being, and undermining confidence, mathematics anxiety can impede students’ ability to understand mathematical concepts, solve problems, and achieve academic success. Tobias and Weissbrod (1980) define math anxiety as “the panic, paralysis, and mental disorientation that arises among some people when they are required to solve a mathematics problem” (p. 65). Thus, for the purpose of the study the term “mathematics anxiety” refers to the state of fear, discomfort, and low self-esteem because of difficulty in engaging in mathematical activities.

Despite various efforts to improve students’ mathematics achievement, no significant improvement has been made. For instance, the 2015 Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) report revealed a notable decline in the average mathematics achievement scores of 15-year-old students between 2012 and 2015 in at least one-third of the countries surveyed. This decline was observed in countries such as the United States, China (specifically Hong Kong), and Brazil (OECD, 2016). Researchers have been attempting to unfold various factors for poor math achievement at the school level. One of the factors that plays a central role in math achievement is math anxiety. For example, Ma (1999) and Barroso et al. (2021) reported a negative correlation between school students’ math achievement and math anxiety.

While extensive research has been conducted on mathematics anxiety among school students, there is a notable gap in research focusing specifically on mathematics anxiety in preservice teachers. Understanding preservice teachers’ experiences, perceptions, and challenges related to mathematics anxiety is essential for developing targeted interventions, support strategies, and professional development opportunities to enhance their confidence, competence, and effectiveness in teaching mathematics in the future. Moreover, addressing issues related to anxiety as early as in mathematics methods courses would further develop a positive feeling toward mathematics. Similarly, exposing preservice teachers to the field (school) during the mathematics methods course increases confidence, alleviating mathematics anxiety. In fact, field placement, along with methods courses, has been one of the essential ways to provide early exposure for preservice teachers to prepare for future teaching. These practical experiences provide preservice teachers with early exposure to classroom settings, instructional strategies, and professional responsibilities, enhancing their readiness and confidence as future educators (Everling et al., 2015). Investigating this underexplored area allows educators, researchers, and policymakers to better understand the anxiety-related challenges experienced by preservice teachers and design evidence-based strategies that foster their professional development and success in teaching mathematics.

1.1. Theoretical Background

Mathematics anxiety is generally characterized by feelings of fear, discomfort, and low self-esteem when engaging in mathematical activities. This anxiety can affect individuals of all ages, often leading to the avoidance of math-related tasks and negatively impacting academic and career opportunities. It typically involves emotional, behavioral, and cognitive responses to perceived threats to self-esteem in math-related situations (Olango, 2016). Math anxiety can have significant consequences for students, including poor performance in mathematics. Individuals with high levels of math anxiety tend to achieve lower levels of math competence and performance (Ashcraft & Kirk, 2001; Ashcraft, 2002). Moreover, those with severe anxiety often avoid engaging in mathematics learning, further contributing to their lower achievement in the subject.

Mathematics anxiety is not an inherent trait but rather a learned response that develops over time and is influenced by various factors, such as the school environment, instructional strategies, and other contextual elements. School environments play a vital role in shaping students’ beliefs toward math. The mathematics courses taken, the way mathematics courses are taught, and the negative attitudes or beliefs toward these courses particularly increase math anxiety (Mainali, 2022). For instance, Hill and Bilgin (2018) reported that preservice teachers who took a math course in their final year of high school also had lowered math anxiety going into their teacher training programs. Similarly, students who performed poorly in mathematics during their time in school are more anxious and believe that they could not learn math even at the college level (Olson & Stoehr, 2019). Regardless of what stage math anxiety develops at, several studies reported that it is negatively correlated with student math performance (Foley et al., 2017; Hembree, 1990; Ma, 1999). Several studies have explored the relationship between math anxiety and math performance, identifying three main theoretical perspectives: the Deficit Theory, the Debilitating Anxiety Model, and the Reciprocal Model. The Deficit Theory posits that math anxiety arises as a result of low mathematical achievement (Sorvo et al., 2019). In contrast, the Debilitating Anxiety Model suggests that math anxiety negatively impacts mathematical performance, either by causing individuals to avoid math-related activities or by directly interfering with cognitive processes involved in the retrieval and processing of mathematical information (Carey et al., 2016; Choe et al., 2019; Finell et al., 2022). The Reciprocal Model integrates both perspectives, proposing a bidirectional relationship between math anxiety and mathematical performance. Brady and Bowd (2005) argue that mathematics anxiety partially stems from the type of instruction encountered in school, often beginning as early as the elementary level. Bandura’s (1986) Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) highlights the dynamic interaction between personal factors, behaviors, and environmental influences in shaping how individuals learn, including their experiences with mathematics. Researchers have primarily focused on three key areas—motivation, emotion, and cognitive support—as strategies for reducing math anxiety (Sammallahti et al., 2023). For preservice teachers, observing experienced educators serves as a powerful tool for learning effective teaching practices and building confidence. Watching successful teaching strategies provides models for emulation and motivates preservice teachers to adopt these approaches, which can help alleviate anxiety. Additionally, the interplay between preservice teachers’ personal experiences, teaching behaviors, and the learning environment plays a crucial role in shaping their motivation to become teachers and reducing their anxiety levels. Positive reinforcement from mentors and peers further enhances confidence and alleviates anxiety. Incorporating interactive field experiences, employing engaging instructional methods, and fostering a supportive classroom environment can also help mitigate mathematics anxiety (Sloan, 2010). Thus, while mathematics anxiety may develop early, targeted interventions and effective instructional practices have the potential to significantly reduce its impact over time.

1.2. Rationale

The existing literature indicates a negative correlation between mathematics anxiety and mathematics performance, suggesting that individuals with higher levels of mathematics anxiety are less likely to be effective in teaching mathematics lessons. Additionally, individuals who have more math anxiety likely have a negative attitude toward teaching and learning mathematics. Thus, the experience of math anxiety can have detrimental effects on students’ math performance (Sammallahti et al., 2023), regardless of their ages and grades. Apparently, teachers with a negative attitude toward mathematics are less likely to be effective in teaching mathematics, thus it is very important for preservice teachers to have a positive attitude towards mathematics in order to create curiosity and enthusiasm for their future students. In fact, more anxious students tend to avoid mathematical activities (Dowker et al., 2016). Preservice teachers who experience high levels of mathematics anxiety are more likely to avoid engaging in mathematical activities, which can ultimately make them less effective when teaching mathematics in class. Furthermore, mathematics anxiety can have long-term implications for preservice teachers’ academic and professional trajectories, potentially limiting their success in becoming effective classroom teachers. More importantly, teachers in elementary schools have a particularly strong impact, often passing their own math anxiety onto their students (Furner & Berman, 2003). Therefore, addressing mathematics anxiety in preservice teachers is crucial to ensure they can confidently and competently teach mathematics to diverse student populations in their future classes.

A substantial body of research has been conducted on mathematics anxiety, particularly at the school level. However, comparatively little research has focused on undergraduate preservice teachers at the college level. For example, in a systematic review of math anxiety interventions, Balt et al. (2022) identified over 30 studies, all centered on school mathematics. Given the critical influence teachers have on their students, it is essential to investigate math anxiety among preservice teachers who will ultimately become classroom teachers. In fact, it is crucial to address and reduce mathematics anxiety among preservice teachers to empower them to succeed and thrive in their teaching careers. For example, persons who have mathematics anxiety have limited success in college majors and career choices (Levine, 1996). Previous research has indicated that elementary education majors exhibit higher levels of math anxiety compared to individuals in other college majors, such as those in the social sciences and business disciplines (Hembree, 1990). This elevated level of math anxiety among prospective teachers may have both immediate and long-term implications for the students they teach, potentially affecting the quality of instruction and student outcomes in mathematics. Therefore, it is important to reduce, if not eliminate, mathematics anxiety in preservice teachers because mathematics anxiety leads to doubts pertaining to their potential effectiveness in teaching mathematics in elementary schools (Trice & Ogden, 1986). Understanding the primary causes of mathematics anxiety in preservice teachers and addressing them through targeted strategies can help reduce anxiety, fostering greater confidence and effectiveness as they begin their teaching careers. In this regard, the following research questions are posed:

- What are the primary causes of mathematics anxiety among preservice teachers?

- What is the relationship between mathematics anxiety and mathematical achievement in preservice teachers?

- How does field placement influence preservice teachers’ mathematics anxiety?

1.3. Related Literature

Mathematics anxiety has long been a focus of research in mathematics education. Studies consistently show a negative correlation between math anxiety and math performance, indicating that higher levels of anxiety are often associated with lower scores on math tests and assessments. The negative correlation between math anxiety and mathematical performance is a global issue, with math anxiety emerging as early as elementary school (Foley et al., 2017). Foley et al. (2017) further state that several factors may contribute to the development of math anxiety, including the amount and quality of mathematical input from parents and teachers, societal pressures, and prevailing stereotypes. Hembree’s (1990) meta-analysis revealed a persistent negative relationship between math anxiety and math achievement across numerous studies. Additionally, the research examines the broader impact of math anxiety on long-term outcomes, such as academic success, course selection, and career choices. Luttenberger et al. (2018) emphasized that math anxiety can result in the avoidance of math-related fields, thereby restricting career opportunities. Maloney and Beilock (2012) reported that early experiences with math can lead to the development of math anxiety, which in turn negatively impacts mathematical performance. Students with higher levels of math anxiety tend to perform worse on math-related tasks (Ashcraft & Krause, 2007). One possible reason for the negative correlation between mathematics anxiety and actual performance is that individuals with higher levels of math anxiety tend to avoid engaging in activities and situations that require the use of mathematics (Dowker et al., 2016).

Ma (1999) conducted meta-analyses on 26 studies and found a significant relationship between anxiety and mathematics achievement, where math anxiety has a negative effect. Similarly, Wen and Dubé (2022) conducted a systematic review of 95 studies and reported that enjoyment, self-concept, confidence, perceived value, and behavioral intentions positively impact mathematics achievement, whereas anxiety and gender are negatively related to achievement. In fact, highly math-anxious individuals end up with lower math achievement and competence (Ashcraft & Kirk, 2001; Ashcraft, 2002). Because of the negative effects of mathematics anxiety, studies have attempted to unfold various sources that create mathematics anxiety. One of the main reasons for mathematics anxiety is related to negative classroom experiences (Bekdemir, 2010). Some other research reported that some of the main sources of mathematics anxiety comprised negative math classroom experiences and attitudes, difficulty in understanding the concepts, math testing, and homework (Mainali, 2022; Clark, 2013; Harper & Daane, 1998; Peker & Ertekin, 2011). Olson and Stoehr (2019) reported that the top three factors causing math anxiety consist of tests, pop-up quizzes, and exams. For instance, the pressure of high-stakes tests and the emphasis on performance can increase anxiety levels (Clement, 2016). Similarly, time constraints, such as those in timed math assessments, can trigger math anxiety (Hunt & Sandhu, 2017). Math anxiety can be caused and influenced by various factors, such as predispositions, effects on math performance, personal and environmental impacts, self-efficacy, teacher attitudes, and instructional approaches. Although much research remains to be performed to explore the many facets of mathematics anxiety, the influence of mathematics teachers and their instructional methods appears to play a significant role in either exacerbating or alleviating this anxiety (Rada & Lucietto, 2022). For example, Luttenberger et al. (2018) suggest that math teachers may inadvertently perpetuate the misconception that math is a natural ability or that mathematical success relies on inherent talent and intellect, irrespective of factors such as gender, geography, or ethnicity. Consequently, having a teacher with a positive attitude towards mathematics is crucial in shaping students’ perceptions and reducing math anxiety. Emphasizing conceptual understanding, making real-life connections to math, and fostering a sense of purpose in learning mathematics are likely to motivate students and alleviate anxiety. Conversely, an emphasis on memorization and speed, rather than understanding and accuracy, can increase math anxiety and diminish confidence in mathematical problem-solving skills (Geist, 2010). Additionally, math projects and open-ended assignments can help reduce math anxiety, while high stakes standardized tests and timed assessments often exacerbate it (Furner & Berman, 2003). For example, removing time constraints during assessments has been shown to lessen the effects of math anxiety on performance (Faust et al., 1996).

Barroso et al. (2021) conducted a meta-analysis of math anxiety and math achievement. This meta-analysis, which examined 223 studies and included 747 effect sizes, explored the relationship between math anxiety and math achievement. The findings revealed a small-to-moderate negative correlation, indicating that individuals with higher levels of math anxiety generally demonstrate lower math achievement. They further suggested that the relationship is complex, and may depend on many factors such as the nature of the content, school environment, instructional strategies, etc. Furthermore, the association between math anxiety and math achievement is significant across different developmental periods, from early childhood through adulthood, including preservice teachers. Not only does the actual mathematics content that preservice teachers learn impact anxiety but also various other factors such as classroom and teaching environment. For instance, supportive and encouraging environments can help reduce anxiety, while unsupportive environments can exacerbate it (Gresham, 2021). Preservice teachers themselves have low morale and lack of confidence towards mathematics and have prejudice towards teaching and learning mathematics, creating math anxiety. The lack of confidence in their own ability to understand mathematical concepts and procedures can contribute to increased anxiety (Clement, 2016).

A range of strategies and interventions can be employed to alleviate math anxiety. These interventions primarily focus on the school environment, instructional strategies, and providing motivational, cognitive, and psychological support. For example, promoting a growth mindset—where individuals believe their abilities can improve through effort—has been shown to decrease math anxiety and enhance mathematics achievement (Hung et al., 2014). Addressing math anxiety in preservice teachers is especially crucial as they, directly and indirectly, influence their future students. Research indicates that teachers with high levels of math anxiety may unintentionally pass it on to their students (Beilock et al., 2010). Furthermore, research indicates that students may absorb math anxiety exhibited by their teachers, which can negatively impact their math performance (Ramirez et al., 2018). Therefore, tackling math anxiety early, before individuals enter the teaching profession, is vital. Effective interventions during this period can help future teachers overcome their anxiety, foster a positive attitude toward teaching math, and ultimately benefit their students (Uusimaki & Nason, 2004). Uusimaki and Kidman (2004) further highlighted that feeling comfortable or uncomfortable with mathematics is not necessarily tied to ability but rather to anxiety, which disrupts the learning process. They noted that fear of failure and excessive worry can negatively affect performance, even when the tasks are well within the individual’s skill level, as is often the case with preservice teachers.

Various strategies have been utilized to reduce preservice teachers’ mathematics anxiety. One of the important strategies that recently gained wide popularity is field-mediated mathematics methods courses. The early exposure of preservice teachers in the field not only reduces mathematics anxiety but also increases confidence. Thus, in the last couple of decades, teacher educators have increasingly emphasized the importance of field-mediated courses for preservice teachers, including student teaching (Maandag et al., 2007; Ronfeldt & Reininger, 2012; Jacobs et al., 2017). Field placements enable preservice teachers to form meaningful connections with classroom students, characterized by their commitment, closeness, and enthusiasm, shaped by the school environment (Shelton et al., 2020). Furthermore, Jacobson (2017) suggested that instruction-focused field experiences, especially those introduced early on, are strongly associated with mathematical content knowledge, active learning beliefs, and math-as-inquiry-based learning. In fact, Zeichner (2010) suggested a stronger integration of field experiences with academic coursework to better prepare preservice teachers, rather than the traditional model. Examining and understanding mathematics anxiety and finding strategies to alleviate it are crucial for successful learning and teaching mathematics (Gresham, 2018).

Despite the importance of field placement, a meager amount of research has been performed to examine the role of field experiences in undergraduate mathematics method courses and even fewer studies focus on mathematics anxiety and the effect of field placement in preservice teachers. Studies that have been conducted on this subject reported a positive effect of field placement on preservice teachers (Ronfeldt & Reininger, 2012; Darling-Hammond & Hammerness, 2005). For example, feedback from supervisors or cooperating teachers during the field placement has a positive impact on preservice teachers (Fernandez & Erbilgin, 2009; Murray et al., 2008). O’Brian et al. (2007) further suggested that the relationship between preservice teachers and cooperating teachers is crucial for the development and growth of preservice teachers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Participant

The study employs a mixed-methods research design, where three different instruments were used to collect both qualitative and quantitative data. In a convergent parallel design, quantitative and qualitative data are collected simultaneously, analyzed independently, and subsequently integrated during the interpretation phase. The study took place at a liberal arts private university in the eastern state of the United States during the spring semesters of 2022 and 2023. One of the researchers served as the course instructor, and participants were recruited from an undergraduate mathematics methods course within a teacher education program. The study’s sample comprises 44 preservice teachers enrolled in a mathematics methods course, titled “Teaching Mathematics at Elementary School.” This is a mandatory course for all preservice teachers who are majoring in elementary education and is typically completed during their junior year of study. A key component of the methods course is the field placement, which provides preservice teachers with hands-on teaching experience in a real-world classroom setting. During their field placement, students are required to complete a specified number of hours at a local school district, where they have the opportunity to observe, assist, and teach mathematics lessons under the guidance of cooperating teachers. As a part of the teacher education program, students were required to take general education courses, teacher education core courses, and courses in their minor track. This study was conducted during a mathematics methods course in junior/senior years during the program. The study received approval from the University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), and informed consent was obtained from each participant at the outset of the research.

2.2. Research Instruments and Data Collection

The study employed four distinct instruments: a Mathematics Anxiety Rating Scale (A-MARS), a concept map, Praxis Core test, and a set of questionnaires with field notes and reflections. The Abbreviated Mathematics Anxiety Rating Scale (A-MARS) is a shortened version of the original Mathematics Anxiety Rating Scale (MARS), developed to efficiently assess individuals’ levels of mathematics anxiety. A standardized instrument utilized since 1970, the A-MARS assesses participants’ levels of mathematics anxiety, providing quantitative data on their anxiety levels and related symptoms. Consisting of 25 items, the A-MARS asks respondents to rate their anxiety in various math-related situations, such as taking tests, solving problems in public, or working with specific mathematical concepts. It uses a Likert-type scale, typically ranging from low to high anxiety, to provide a quantitative measure of discomfort or apprehension toward mathematics. A-MARS is considered a valid and reliable tool for measuring math anxiety. Validation studies (including Suinn & Winston, 2003, and later research) have shown that it maintains strong correlations with the original full MARS while preserving its psychometric integrity. The reliability coefficient of the tool for the twenty-five items was measured with Cronbach’s alpha (α = 0.95) on the study sample of 44 participants.

One of the instruments utilized in this study was a concept map, which has been a useful diagnostic and research tool (Buhmann & Kingsbury, 2015). Concept maps are essentially visual tools for organizing and representing knowledge (Kinchin et al., 2010). It is important to utilize multiple representations in teaching and learning mathematics (Mainali, 2021). For instance, concept maps—serving as diagrammatic representations—facilitate the integration of various ideas by explicitly illustrating their interconnections. In fact, a concept map helps to examine the relationship and pattern within the data (Kinchin et al., 2010). In the visual representation form, participants have opportunities to express their ideas in a free-flow manner in the concept map. Moreover, a concept map can be reviewed quickly, allowing participants to complete more passes, ideas, and thoughts through given information (Nesbit & Adesope, 2006). Because of the visual nature of concept maps, it offers a multidimensional aspect of the ideas expressed in the map, in contrast to verbal representation (Grevholm, 2008). Thus, concept maps serve as visual tools for organizing and representing knowledge, enabling participants to visually connect various ideas and concepts related to mathematics anxiety, teaching strategies, and classroom experiences (Kinchin et al., 2010). Participants were given concept maps to draw on a blank sheet of paper, with “Math Anxiety” given at the center of the paper. The researcher explained the basic idea of concept maps, demonstrating some examples as how to complete the concept map before they were given the maps to complete.

The quantitative data was collected via an Abbreviated Mathematics Anxiety Rating Scale (A-MARS) (Suinn & Winston, 2003; Brush, 1978), whereas a concept map and questionnaires were used to collect the qualitative portion of the data. The A-MARS and concept map were administered at the beginning of the semester, whereas the questionnaire was distributed near the end of the semester to capture participants’ reflections, experiences, and perceptions following their field placement and teaching experiences. Preservice teachers are required to take the Praxis test as part of teaching licensure. The Praxis Core tests are designed to assess the fundamental academic skills of individuals entering teacher preparation programs.

The Praxis test is designed and conducted by the Educational Testing Service (https://praxis.ets.org, 1 January 2025), which measures reading, writing, and mathematics skills. The Praxis-mathematics section serves as a critical assessment tool for evaluating preservice teachers’ achievement and preparedness to obtain a teaching license. The test is reliable and valid since “ETS states that as a part of our mission to help advance education quality and equity by providing fair assessments, we put our test questions through a rigorous review process” (Educational Testing Service, n.d.). The Praxis test scores range from 100 to 200, with passing requirements varying by state. In most states, including the one where this research was conducted, the passing score for mathematics typically falls between 150 and 162. Thus, the Math Praxis score is used as participants’ mathematical performance. In accordance with state regulations, preservice teachers are required to pass the Praxis Core test before enrolling in methods courses, including undergraduate mathematics methods courses offered within the Department of Teacher Education. Consequently, all participants in this study had successfully completed the Praxis Core test prior to enrolling in the mathematics methods course. An exception to this requirement applies to preservice teachers who have achieved an acceptable score on the Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT), in which case the Praxis Core test is not mandatory. Upon completion of the Praxis Core test, candidates’ scores are automatically transmitted to their profiles within the teacher education program at their respective universities. This is facilitated by the requirement that examinees designate their score-reporting institution when registering for the Praxis assessment through the Educational Testing Service (ETS).

A concept map and a set of questionnaires were used to collect the qualitative data for the study. A set of five questions, including reflective prompts and open-ended questions, were administered to collect qualitative data on participants’ experiences, challenges, and insights related to mathematics anxiety and teaching mathematics during their field placement. The five questions asked participants to explain topics such as the following: Does the field placement help to decrease (or increase) math anxiety? Why and how does the field placement help to decrease (or increase) math anxiety? Would you like to share anything about field placement and math anxiety? These questions, integrated as part of the course assignment, enabled participants to articulate their reflections, feelings, and observations about mathematics anxiety following their teaching experiences in the classroom.

The qualitative data from the open-ended questions were analyzed using a codebook that was developed during the data analysis process to identify emerging themes. Each of the forty-four participants’ responses were entered into a Microsoft Excel sheet, with participant names listed in rows and their answers to the five open-ended questions recorded in separate columns. An emergent coding scheme (Marshall & Rossman, 2006) was utilized to organize the qualitative data, where narratives of each participant were sorted. For clarity and transparency, different colors were assigned to each participant and to each question in the spreadsheet. Data were then compared horizontally for each open-ended question across participants. In the second stage, preliminary themes for each question were identified and subsequently verified across participants before finalizing the themes. The codebook was continuously refined throughout the analysis, as coding is an iterative process of organizing and interpreting collected data (Glesne, 2011). The final themes were drawn from the qualitative data and compared and contrasted among participants.

3. Results

3.1. A-MARS

The Abbreviated Mathematics Anxiety Rating Scale (A-MARS) consists of 25 Likert scale questions that aim to measure mathematics anxiety. For more details, please look at the appendix. The analysis of the data revealed that most of them possess high mathematics anxiety. Out of the total participants, only one participant shows no mathematical anxiety at all, whereas 20 (44%) participants are very anxious about mathematics. The anxiety level is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of A-MARS.

The mean anxiety score ranges from as low as 1 to as high as 5. The descriptive statistics of the A-MARS are given in Table 1.

The A-MARS scores ranged from 1 (not anxious) to 5 (very anxious), with 2 indicating little anxious, 3 indicating anxious, and 4 indicating very anxious. For the descriptive purpose, the anxiety score of 2 and above indicates students have math anxiety. The five items with the highest mean scores were item 15 (M = 3.61, SD = 1.12), item 9 (M = 3.59, SD = 1.28), item 4 (M = 3.52, SD = 1.26), item 8 (M = 3.09, SD = 1.13), and item 2 (M = 3.00, SD = 1.34), all of which were related to mathematics tests, quizzes, and examinations. These results indicate that traditional classroom assessments are a leading source of math anxiety among preservice teachers. Item 18 (M = 1.43, SD = 0.66) recorded the lowest anxiety score, and none of the items received a score of 1. This indicates that all preservice teachers experience at least some degree of math anxiety, despite variations in anxiety levels among participants.

A Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to evaluate the linear relationship between anxiety scores and mathematics scores. The results indicate a statistically significant negative correlation between anxiety and mathematics performance (r = −0.316, p < 0.05). This suggests that as mathematics scores increase, anxiety levels tend to decrease, with the two variables moving in opposite directions. The test result is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Pearson Correlation result.

The table above indicates a sample size of N = 40 since four participants did not have Praxis Core test scores due to having taken the SAT assessment instead. The findings indicated that preservice teachers who made more associations related to mathematics anxiety tended to have higher anxiety scores on the A-MARS. Preservice teachers identified test anxiety as a significant source of mathematics anxiety. Additionally, preservice teachers listed various sources of mathematics anxiety, underscoring the multifaceted nature of this phenomenon in mathematics education.

3.2. Concept Map

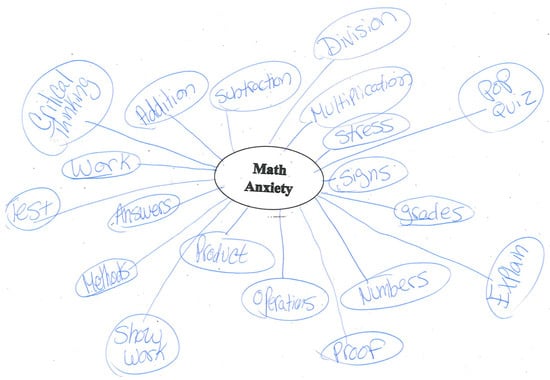

Concept maps were analyzed by focusing on key nodes, node links, crosslinks, and the various mathematical domains represented in the maps. A key node represents a central idea or concept that serves as the foundation for constructing the concept map. A node corresponds to ideas, phenomena, or related terms within the concept map that are connected to key nodes. Links are the lines that connect key nodes to other nodes, while crosslinks refer to the lines that connect different nodes within the concept map. The physical size and hierarchical structure of the concept map were not considered in the analysis. For the purpose of analysis, the number of nodes, their nature, and their characteristics in conjunction with key nodes (math anxiety) were examined. An example of a sample work of the concept map is given below, which has 19 nodes. The participant used 19 links to connect various nodes to express her math anxiety. Various factors can be noticed that are associated with mathematics anxiety as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Concept map of one of the participants.

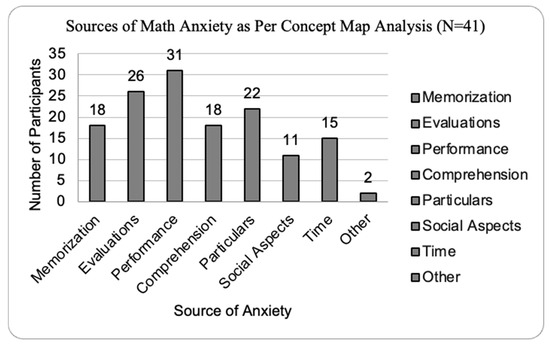

A total of 41 participants completed the math anxiety concept map. The number of nodes created by each participant varied, with the highest number being 19 and the lowest being 3. An overall analysis of the concept maps revealed a total of 247 nodes related to math anxiety. The most frequently mentioned concerns were related to grades, tests, quizzes, and homework. Among these, the top three factors contributing to math anxiety in preservice teachers were tests (15 mentions), homework (13 mentions), and grades (13 mentions). The summary of the main factors associated with math anxiety is given in Figure 2. The various factors identified through the concept maps can be further categorized as described below:

Figure 2.

Various sources of math anxiety.

Memorization and Comprehension: This category encompasses the memorization and understanding of various mathematical concepts and the anxiety factors associated with them. The analysis revealed that many participants face difficulties in memorizing formulas and rules, as well as understanding and applying mathematical procedures in different contexts. These challenges are identified as significant contributors to mathematical anxiety.

Evaluation and Performance: This category includes various factors associated with mathematical assessments and performance. Anxiety related to grades, tests, quizzes, and homework emerged as the most frequently mentioned contributor to math anxiety. Additionally, factors such as pop quizzes, timed tests, poor grades on assignments and exams, and restrictions like the absence of calculators during tests were also identified as significant contributors to mathematical anxiety.

Particular Topics/Areas: This category consists of various factors directly linked to the mathematical content areas involved in teaching and learning mathematics at the elementary school level. Topics such as geometry, fractions, word problems, algebra, proportions, and percentages often contribute to the development of math anxiety. Additionally, challenges posed by complex word problems, calculus, and non-standard algorithms further exacerbate mathematical anxiety.

Social Aspects and Emotions: This group includes various factors that are indirectly related to the teaching and learning of mathematics. Key factors include emotions such as tears, panic, frustration, hesitation, and confusion. Additionally, anxiety stemming from teaching methods, social comparisons, and emotional aspects like stress, uncertainty, and general anxiety also contribute significantly to the development of math anxiety.

3.3. Field Experience

The data analysis reveals responses reflecting a range of experiences regarding the impact of field placement on mathematics anxiety. While few participants found the field placement/experience increased their math anxiety due to unfamiliarity with the students and school curriculum, the majority reported a reduction in anxiety because of the field placement. Thirty-three participants stated that their mathematics anxiety reduced, three students stated their anxiety increased, and three students stated their anxiety neither increased nor decreased after completing the field placement. The anxiety reduction often came from increased confidence through practice, observing experienced teachers, receiving feedback, and becoming more comfortable in a teaching role. The main five themes that emerged as being helpful in reducing math anxiety are as follows: (I) support and guidance from cooperating teachers, (II) classroom dynamics and exposure to teaching, (III) impact of observations and real-world practice, (IV) personal comfort and confidence in math content, and (V) lack of preparedness and unfamiliarity with students. The main five themes that emerged are further explained below:

Support and guidance from cooperating teachers: Most participants reported that their math anxiety decreased due to the support and guidance provided by their cooperating teachers. Observing lessons, receiving feedback, and having a supportive environment helped them feel more comfortable and confident in teaching math. The analysis further revealed that the presence of a cooperating teacher who provided feedback and support was crucial in reducing anxiety. Constructive criticism and positive reinforcement helped participants feel more prepared and less anxious. For example, one participant stated, “My cooperating teacher always provided me with important feedback, particularly at the end of teaching mathematics lessons. I have always felt comfortable getting up in front of a class and teaching a math lesson since my cooperating teacher was very encouraging during the field experience.” Additionally, the analysis showed that watching and observing the cooperating teacher teach math lessons significantly helped reduce math anxiety. Having a cooperating teacher as a role model in the classroom, who demonstrated various teaching strategies and provided clear examples of effective teaching practices, further helped reduce math anxiety. Another participant noted, “I had observed how the teacher carried out her math lessons and felt better once I had a model to follow.”

Therefore, the support and guidance from cooperating teachers were crucial factors in reducing math anxiety during the field placement.

Classroom dynamics and exposure to teaching: The data analysis indicates that repeated exposure to teaching math lessons, whether individually or in groups, helped alleviate anxiety for most participants. Gaining practical teaching experience and becoming familiar with the classroom environment and teaching process were key factors in reducing anxiety. Building rapport with students and understanding their unique learning styles during the field placement also contributed to lowering participants’ math anxiety. Recognizing students’ strengths and needs during the field placement allowed participants to feel more at ease when teaching math lessons. For instance, one participant shared, “It got easier as time went on during the lesson. I was comfortable and familiar with the students, which made it more relaxed.” Additionally, the analysis suggested that a welcoming and engaging classroom environment fostered by the cooperating teacher and students further reduced anxiety. Another participant noted, “The students were always excited to see us and really wanted to participate in our lessons. This made me less anxious than I would have been otherwise”.

Impact of observations and real-world practice: Observing various teaching styles and participating in practical teaching experiences enabled participants to explore diverse approaches and strategies for teaching math lessons. The data indicated that field placement in elementary schools allowed participants to witness the real-world application of their knowledge, which helped to reduce math anxiety by enhancing their adaptability and resilience in the classroom. For instance, one participant shared, “I had observed how the teacher carried out her math lessons and felt better once I had a model to follow.” The analysis further revealed that several participants reported a decrease in math anxiety as they gained more experience teaching math lessons. Engaging in practice teaching allowed participants to grow more comfortable and confident in their ability to teach math effectively. For example, one participant stated, “The field placement helped to reduce some of my mathematics anxiety. I was nervous prior to teaching my lesson, but after a few minutes into my lesson, I got comfortable.” Similarly, field placements offered invaluable real-world teaching opportunities. Being in an actual classroom setting and teaching multiple lessons provided participants with hands-on experience that significantly reduced their anxiety. Another participant noted, “I think this field placement helped to reduce my mathematics anxiety. I was nervous to teach the group lesson because I had never taught math before. After the group lesson, my anxiety went down”.

Personal comfort and confidence in math content: Some participants expressed minimal or no anxiety, attributing this to their confidence in their mathematical abilities. For these individuals, the field placement served as a reinforcement of their skills and had little to no impact on their anxiety levels.

Lack of preparedness and unfamiliarity with students: Several participants reported an increase in mathematics anxiety due to feeling unprepared or unfamiliar with the students’ learning levels, prior knowledge, and individual needs. The analysis revealed that the initial experience of teaching math lessons heightened participants’ anxiety, particularly due to challenges with classroom dynamics, students’ abilities, and effective instructional strategies. For instance, one participant shared, “At first, my anxiety increased a little because first graders seemed a lot more advanced compared to when I was in the first grade.” However, despite these initial difficulties, many participants noted a gradual decrease in anxiety as they adjusted to the teaching environment and gained confidence in their abilities. For example, another participant stated, “As the math methods course went on and as I was in the field for more days, my math anxiety was reduced. This course really helped me learn some of the strategies I saw the students using during the field placement.”

3.4. Field Placement: Summary

The data analysis indicated several factors that contributed to the reduction in mathematics anxiety among participants during field placements. Key reasons included practical teaching experience, constructive feedback, positive interactions with students, and opportunities for observation and reflection. For instance, one participant stated,

Being in the field helped reduce my math anxiety by interacting with the students, receiving feedback on my lessons, conferencing with my cooperating teacher immediately after teaching a lesson, hearing what I did well and what I could improve on, having the opportunity to ask questions, and gaining experience teaching a group of students.

Similarly, the analysis revealed that reflecting on lessons, discussing successes, and identifying areas for improvement with cooperating teachers were instrumental in alleviating anxiety. One participant noted, “Watching experienced teachers deliver math lessons provided a model to follow and helped us understand effective teaching strategies, thereby reducing anxiety about our own teaching”.

Direct interaction with students also emerged as a significant factor in reducing anxiety. This included observing students’ reactions to lessons, witnessing their comprehension of concepts, and engaging with them during classroom activities. Furthermore, the process of lesson preparation and delivery, especially in collaboration with a partner, provided a structured and supportive approach, which further alleviated anxiety. One participant explained,

The field placement helped reduce my math anxiety. Being surrounded by caring and encouraging children lowered my anxiety levels. Many students in my class expressed their appreciation for my lessons, which made me feel confident and valued. Knowing that the students cared about my success and were supportive of my efforts helped me stay calm and focused during the placement. Additionally, developing positive relationships with students and understanding their learning needs significantly reduced participants’ anxiety. Familiarity with students’ prior knowledge and learning strategies allowed participants to design lessons tailored to the students’ needs, further boosting their confidence. As one participant stated, “Getting to know the students in the class and understanding how they learn was incredibly helpful. I was able to base my lessons on what they were already learning and the strategies they were familiar with, which reduced my math anxiety.” In summary, field placements provided participants with opportunities to build practical teaching skills, engage in meaningful interactions, and reflect on their experiences, all of which played a crucial role in reducing mathematics anxiety.

The analysis of the data indicated that while some participants continued to experience nervousness or anxiety before or during their teaching of a mathematics lesson, the majority reported a decrease in anxiety following the successful completion of the lesson. Only two participants noted an increase in their levels of mathematics anxiety after teaching during the field placement. The findings highlighted a range of experiences with mathematical anxiety among the participants. For some individuals, relief or a reduction in anxiety occurred as a result of positive teaching experiences, such as when lessons were executed successfully, students demonstrated understanding of the material, or participants felt confident and adequately prepared. Conversely, a subset of participants who did not initially report mathematics-specific anxiety experienced generalized anxiety related to teaching or being evaluated. A small number of participants expressed that their anxiety either remained unchanged or might increase in subsequent lessons. This concern was primarily attributed to apprehensions about their ability to address students’ questions effectively or fully comprehend the students’ cognitive processes.

The data analysis identified several additional factors that contributed to reducing participants’ math anxiety following the teaching of math lessons. Key factors included receiving positive feedback from cooperating teachers, observing student engagement during the lesson, witnessing students’ comprehension of mathematical concepts, and the opportunities for reflection and adaptability. The analysis suggested that teaching a math lesson often leads to a reduction in anxiety for teachers, as the successful completion of the lesson boosts their confidence and alleviates initial nervousness. For instance, one participant noted,

My math anxiety level decreased after teaching the math lesson. I think once I began, everything progressed smoothly. The students actively participated and asked numerous questions. Their questions and engagement helped the lesson flow effectively, allowing me to cover all the required content.

Furthermore, the analysis indicated that despite initial anxiety prior to teaching, participants found reassurance in students’ active engagement and participation, which helped alleviate their stress and anxiety. As one participant explained,

My mathematical anxiety significantly decreased after teaching this lesson because I felt more confident and knowledgeable about the subject. I also recognized that even if I made a mistake or deviated from my original plan, the students would not notice, emphasizing the importance of adapting and persevering through challenges.

Similarly, another participant shared,

Initially, seeing all their eyes on me made me anxious, but I reminded myself that I already knew the students well, having worked with them for several weeks. The pressure of teaching eased once the lesson was complete, and I felt confident in the material I presented. Additionally, observing their work and realizing they had grasped the concept further reduced my anxiety and allowed me to feel at ease.

Some participants reported an increase in anxiety levels after teaching math lessons. This heightened anxiety appeared to be primarily attributed to general nervousness related to teaching rather than specific mathematics-related anxiety. Key concerns included managing unexpected questions, sustaining student engagement, and effectively delivering the lesson. For instance, one participant stated,

I was very nervous about speaking in another language to students and concerned about whether they would fully grasp the concept as it was taught. I was extremely anxious that they might lose interest in the lesson and stop paying attention. My nervousness was more about the act of teaching in general rather than math anxiety.

Another participant echoed similar sentiments, stating,

I am not anxious about math in general; I find it fascinating because it is so applicable to real life and can significantly boost confidence. However, teaching provided me with valuable insight into how I might improve my approach to teaching a whole-class math lesson, particularly in managing attention spans and addressing the need for differentiated support. Therefore, the analysis contended that field placement seems to be one of the important elements of the math methods course that helps to reduce mathematics anxiety in elementary preservice teachers.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrated a negative correlation between mathematics anxiety and mathematics performance, aligning with prior research (Maloney & Beilock, 2012; Ashcraft & Krause, 2007; Dowker et al., 2016). While earlier studies predominantly focused on school-age students, this research highlights a similar trend among preservice teachers at the college level. The results suggest that the adverse relationship between mathematics anxiety and performance persists across different educational stages. These findings corroborate those of Ma (1999) and Barroso et al. (2021), who also identified a negative relationship between math anxiety and achievement, indicating that higher levels of anxiety are associated with lower academic outcomes.

The study identified several factors contributing to math anxiety among preservice teachers. Key sources of anxiety include assessments such as tests and quizzes, homework assignments, and the memorization of mathematical rules and formulas. Key contributors to mathematics anxiety include assessments and performance such as tests, pop quizzes, and examinations, which align with the findings reported by Olson and Stoehr (2019). Additionally, specific mathematical content areas, including fractions, word problems, algebra, and calculus, further exacerbate math anxiety. These findings are consistent with those reported by Clark (2013) and Peker and Ertekin (2011). Emphasizing project-based work and conceptual understanding, while reducing timed assessments, is likely to lower math anxiety, aligning with findings reported by Faust et al. (1996). Barroso et al. (2021) emphasized the importance of developing interventions to alleviate math anxiety, especially during childhood. Teachers with lower math anxiety and a positive attitude toward teaching and learning mathematics can play a crucial role in reducing math anxiety in their students from an early age. Educators with lower levels of math anxiety are more likely to inspire enthusiasm for learning mathematics in elementary school and encourage students’ engagement with the subject. Cultivating positive attitudes toward math and fostering motivation from an early age can help break the cycle of math anxiety that often emerges later. In fact, a teacher’s approach and attitude toward math provide the foundations for a child to grow and be able to do well in mathematics (Rada & Lucietto, 2022). Therefore, reducing math anxiety among preservice teachers and enhancing their confidence in teaching mathematics is essential. The findings of this study hold significant implications in this context.

The study suggests that field experiences help reduce mathematics anxiety in preservice teachers. When students obtain more chances to interact with students and cooperating teachers, engage in various classroom activities, and explore different mathematical activities in the real classroom setting during the field placement, these factors likely help alleviate anxiety. The findings of the study are consistent with Dowker et al. (2016) who suggest that students who get more involved in mathematics activities are less likely to be anxious about mathematics. As participants engage in classroom activities, they benefit from the guidance and support provided by cooperating teachers, the positive interactions and respect from students, and the confidence developed through classroom exposure. The positive learning environment with the support and guidance of cooperative teachers helps to reduce math anxiety. The findings of this study advocate the study by Gresham (2021), where supportive and encouraging environments can help reduce anxiety while unsupportive environments can exacerbate it. Furthermore, these factors collectively contribute to a reduction in math anxiety, aligning with the findings reported by Wen and Dubé (2022). These various factors underscore the significance of fostering supportive learning environments and equipping preservice teachers with the skills and confidence necessary for effective mathematics instruction. Providing opportunities for field experiences emerges as a critical element in preparing preservice teachers to better support their future students.

The data analysis suggested that some of the main factors causing math anxiety in preservice teachers include tests, exams, pop-up quizzes, memorization, math grades, and evaluation of math work. Notably, the analysis of both A-MARS and the concept maps indicated similar factors contributing to math anxiety in preservice teachers. Furthermore, these factors are also among the primary causes of math anxiety at the school level. Research has shown that math anxiety can begin as early as first grade (Foley et al., 2017). Therefore, math educators should consider alternative forms of assessment and evaluation—particularly in math methods courses—rather than relying solely on tests, quizzes, and exams. Options such as project-based work, cooperative learning, and designing math lesson plans can be valuable alternatives. Indeed, a variety of alternative lesson activities—such as collaborative work, group discussions, exit tickets, and reflective journals—can help reduce mathematical misunderstandings (Hattie & Timperley, 2007) and are likely to alleviate anxiety. Similarly, placing less emphasis on memorization and greater emphasis on conceptual understanding may help reduce math anxiety. Importantly, focusing on how to teach mathematics, rather than simply what to teach, has been shown to positively influence preservice teachers’ math anxiety (Looney et al., 2017). Emphasizing conceptual understanding, explaining the reasoning behind mathematical concepts, and developing critical thinking skills based on mathematical reasoning—rather than relying heavily on standard algorithms—can also help alleviate math anxiety. For example, Looney et al. (2017) found that preservice teachers who began a math methods course with high levels of math anxiety completed the course with reduced anxiety. In fact, the three most significant causes of math anxiety among novice teachers are lack of mastery of the teaching material, difficulty in selecting and applying learning strategies in mathematics, and challenges with classroom management (Syuhada & Retnawati, 2020). Strategically designing math methods courses to foster various aspects of pedagogical content knowledge, encouraging the development of conceptual understanding, providing instructional strategies to help preservice teachers select appropriate mathematical materials, and incorporating field experiences effectively are likely to help reduce math anxiety. Thus, math educators should prioritize strategies to mitigate anxiety during math methods courses in teacher education programs.

5. Implications, Limitations, and Recommendations

This study has some implications, particularly for undergraduate elementary education–preservice teachers at the college level. Mathematics anxiety is recognized as a critical issue in mathematics education, influencing students’ attitudes, perceptions, and achievements in mathematics. As suggested by Barroso et al. (2021), effective interventions that aim to lower math anxiety in students will improve mathematics achievement. Highly math-anxious individuals often exhibit negative attitudes toward teaching and learning mathematics, which can hinder their teaching and learning experiences and academic performance (Suárez-Pellicioni et al., 2016). For instance, research has demonstrated that when parents exhibit higher levels of math anxiety, their children not only show an increase in their own math anxiety but also experience reduced math achievement over the course of the school year (Maloney et al., 2015). Indeed, classroom teachers certainly would have even more impact on students’ mathematics learning and math achievement. In fact, when female elementary school teachers—who make up more than 90% of early elementary educators—display higher levels of math anxiety, their students tend to demonstrate lower math achievement over the course of the school year (Beilock et al., 2010). Students with lower math achievement tend to avoid STEM careers, which is a crucial factor for the prosperity of the nation. For example, students’ math anxiety not only causes them to underperform in math but also to avoid math and math-related careers, resulting in fewer professionals trained in STEM disciplines (Beilock & Maloney, 2015). A less anxious teacher with a positive attitude is likely to develop positive feelings toward math as early as elementary school (Dowker et al., 2016). Thus, it is crucial to have positive feelings and attitudes toward teaching and learning mathematics for preservice teachers. Indeed, teachers with positive attitudes and feelings toward mathematics are likely to be more effective in teaching mathematics lessons and likely to improve students’ mathematics achievement. Therefore, teacher education programs—particularly mathematics methods courses—aim to foster positive beliefs while reducing math anxiety among preservice teachers (Mainali, 2022). Thus, by addressing the underlying causes of mathematics anxiety and promoting positive attitudes and feelings toward mathematics, the study will offer valuable insights and strategies as to how math anxiety can be reduced in preservice teachers. Furthermore, effective educational interventions, even from the early years of schooling, can help manage math anxiety and enhance mathematics learning (Commodari & La Rosa, 2021). Simple measures, such as targeted professional development and mindfulness lessons, can significantly improve teachers’ ability to support students with math anxiety, highlighting the value of systematic training on the topic for all teachers, including preservice teachers (Cruz, 2025). In this regard, as suggested by this study, providing preservice teachers with more extensive field placement experiences during mathematics methods courses would likely help reduce math anxiety. Less-anxious mathematics teachers are more likely to be effective in their instruction, ultimately helping to break the cycle of mathematics anxiety even at the school-level mathematics courses. As mathematics educators, it is our duty to show compassion and assist students in overcoming their math anxiety levels (Lashley, 2004), with classroom teachers playing a crucial role in this effort. We believe that mathematics anxiety is a complex phenomenon that likely requires a coordinated effort among various stakeholders, including teachers/educators, schools, school districts, and curriculum developers. For meaningful and sustainable mathematics education reform, for example, a holistic approach is essential—one that integrates assessment systems, teacher professional development, textbooks and instructional materials, pedagogical strategies, and related elements in a strategically coordinated manner (Mainali, 2025).

This study also had limitations. The sample was relatively small, and the participants were not randomly selected. Furthermore, the findings of this study cannot be generalized since they were based on a small population of preservice elementary teachers. Moreover, this is not a comparative experimental–control group study; a comparative pre–post group design would likely yield more robust results. A larger sample size might have given a different result. The findings of this study suggest that field experience helps to alleviate mathematics anxiety; however, more studies need to be conducted with bigger and more diverse sample sizes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.M.; methodology, B.M.; validation, B.M. and D.S.; formal analysis, B.M. and D.S.; investigation, B.M.; data curtain, B.M. and D.S.; writing original draft, B.M.; writing-review and editing, B.M. and D.S. supervision, B.M.; project administration, B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rider University (date: 1 February 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data and protocol materials presented in this study are available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ashcraft, M. H. (2002). Math anxiety: Personal, educational, and cognitive consequences. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(5), 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcraft, M. H., & Kirk, E. P. (2001). The relationships among working memory, math anxiety, and performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(2), 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcraft, M. H., & Krause, J. A. (2007). Working memory, math performance, and math anxiety. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14(2), 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balt, M., Börnert-Ringleb, M., & Orbach, L. (2022). Reducing math anxiety in school children: A systematic review of intervention research. Frontiers in Education, 7, 798516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, C., Ganley, C. M., McGraw, A. L., Geer, E. A., Hart, S. A., & Daucourt, M. C. (2021). A meta-analysis of the relation between math anxiety and math achievement. Psychological Bulletin, 147(2), 134–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beilock, S. L., & Maloney, E. A. (2015). Math anxiety: A factor in math achievement not to be Ignored. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2(1), 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beilock, S. L., Gunderson, E. A., Ramirez, G., & Levine, S. C. (2010). Female teachers’ math anxiety affects girls’ math achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(5), 1860–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekdemir, M. (2010). The pre-service teachers’ mathematics anxiety related to a depth of negative experiences in mathematics classrooms while they were students. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 75, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, P., & Bowd, A. (2005). Mathematics anxiety, prior experience, and confidence to teach mathematics among pre-service education students. Teachers and Teaching, 11(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, L. R. (1978). A validation study of the Mathematics Anxiety Rating Scale (MARS). Educational and Psychological Measurement, 38, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhmann, S. Y., & Kingsbury, M. (2015). A standardized, holistic framework for concept-map analysis combining topological attributes and global morphologies. Knowledge Management & E-Learning, 7(1), 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, E., Hill, F., Devine, A., & Szücs, D. (2016). The chicken or the egg? The direction of the relationship between mathematics anxiety and mathematics performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cemen, P. B. (1987). The nature of mathematics anxiety. (Report No. SE 048 689/ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 287 729). Oklahoma State University. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, K. W., Jenifer, J. B., Rozek, C. S., Berman, M. G., & Beilock, S. L. (2019). Calculated avoidance: Math anxiety predicts math avoidance in effort-based decision-making. Science Advances, 5(11), eaay1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M. (2013). Teaching the math-anxious female student: Teacher beliefs about math anxiety and strategies to help female students in all-girls schools [Unpublished master thesis, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE), University of Toronto]. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, S. (2016). Math anxiety in pre-service elementary school teachers and its effects on perceived ability to teach mathematics [Unpublished master thesis, Texas Christian University]. [Google Scholar]

- Commodari, E., & La Rosa, V. L. (2021). General academic anxiety and math anxiety in primary school: The impact of math anxiety on calculation skills. Acta Psychologica, 220, 103413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S. E. (2025). A mixed methods study on teacher knowledge and its influence on reducing math anxiety in students [Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, Lindenwood University]. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Hammerness, K. (2005). The design of teacher education programs. In L. Darling-Hammond, & J. Bransford (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 390–441). Jossey-Ba. [Google Scholar]

- Dowker, A., Sarkar, A., & Looi, C. Y. (2016). Mathematics anxiety: What have we learned in 60 years? Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Educational Testing Service. n.d. Available online: https://praxis.ets.org (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Everling, K. M., Delello, J. A., Dykes, F., Joanna, L., Neel, J. L., & Bernadine Hansen, B. (2015). The impact of field experiences on pre-service teachers’ decisions regarding special education certification. Journal of Education and Human Development, 4(1), 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Faust, M. W., Ashcraft, M. H., & Fleck, D. E. (1996). Mathematics anxiety effects in simple and complex addition. Mathematical Cognition, 2, 25–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M. L., & Erbilgin, E. (2009). Examining the supervision of mathematics student teachers through analysis of conference communications. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 72(1), 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finell, J., Sammallahti, E., Korhonen, J., Eklöf, H., & Jonsson, B. (2022). Working memory and its mediating role on the relationship of math anxiety and math performance: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 798090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, A. E., Herts, J. B., Borgonovi, F., Guerriero, S., Levine, S. C., & Beilock, S. L. (2017). The math anxiety–performance link: A global phenomenon. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(1), 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furner, J. M., & Berman, B. T. (2003). Review of research: Math anxiety: Overcoming a major obstacle to the improvement of student math performance. Childhood Education, 79, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geist, E. (2010). The anti-anxiety curriculum: Combating math anxiety in the classroom. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 37(1), 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Glesne, C. (2011). Becoming qualitative researchers: An introduction (4th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Gresham, G. (2018). Preservice to in-service: Does mathematics anxiety change with teaching experience? Journal of Teacher Education, 69(1), 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresham, G. (2021). Exploring exceptional education preservice teachers’ mathematics anxiety. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 15(2), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grevholm, B. (2008, September 22–25). Concept maps as research tool in mathematics education. 3rd International Conference on Concept Mapping, Tallinn, Estonia & Helsinki, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, N. W., & Daane, C. J. (1998). Cause and reduction of math anxiety in preservice elementary teachers. Action in Teacher Education, 19(4), 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hembree, R. (1990). The nature, effects, and relief of mathematics anxiety. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 21(1), 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D., & Bilgin, A. A. (2018). Pre-service primary teachers’ attitudes towards mathematics in an Australian university. Creative Education, 9, 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hung, C. M., Huang, I., & Hwang, G. J. (2014). Effects of digital game-based learning on students’ self-efficacy, motivation, anxiety, and achievements in learning mathematics. Journal of Computers in Education, 1(3), 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, T. E., & Sandhu, K. K. (2017). Endogenous and exogenous time pressure: Interactions with mathematics anxiety in explaining arithmetic performance. International Journal of Educational Research, 82, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J., Hogarty, K., & Burns, R. W. (2017). Elementary preservice teacher field supervision: A survey of teacher education programs. Action in Teacher Education, 39(2), 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, E. D. (2017). Field experience and prospective teachers’ mathematical knowledge and beliefs. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 48(2), 148–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I. M., Streatfield, D., & Hay, D. B. (2010). Using concept mapping to enhance the research interview. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 9(1), 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashley, K. C. (2004). Math anxiety and avoidance of mathematics at the college level: Undergraduate and their sense of not belonging in math classroom [Unpublished master thesis, The City University of New York]. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, G. (1996, April 24–28). Variability in anxiety for teaching mathematics among pre-service elementary school teachers enrolled in a mathematics course. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association in New York, ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED398067, New Orleans, LA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Looney, L., Perry, D., & Steck, A. (2017). Turning negatives into positives: The role of instructional math course on preservice teachers’ math beliefs. Education, 138(1), 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Luttenberger, S., Wimmer, S., & Paechter, M. (2018). Spotlight on math anxiety. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 11, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X. (1999). A meta-analysis of the relationship between anxiety toward mathematics and achievement in mathematics. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 30(5), 520–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maandag, D. W., Deinum, J. F., Hofman, A. W. H., & Buitink, J. (2007). Teacher education in schools: An international comparison. European Journal of Teacher Education, 30(2), 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, E. A., Ramirez, G., Gunderson, E. A., Levine, S. C., & Beilock, S. L. (2015). Intergenerational effects of parents’ math anxiety on children’s math achievement and anxiety. Psychological Science, 26, 1480–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainali, B. (2021). Representation in teaching and learning mathematics. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science, and Technology (IJEMST), 9(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainali, B. (2022). Investigating pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward mathematics: A case study. European Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 10(4), 412–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mainali, B. (2025). USA mathematics education in the last 100 years: Issues, reform, and the lesson learned. British Journal for the History of Mathematics, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, E. A., & Beilock, S. L. (2012). Math anxiety: Who has it, why it develops, and how to guard against it. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(8), 404–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. (2006). Designing qualitative research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, S., Nuttall, J., & Mitchell, J. (2008). Research into initial teacher education in Australia: A survey of the literature 1995–2004. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbit, J. C., & Adesope, O. O. (2006). Learning with concept and knowledge maps: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 76(3), 413–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brian, M., Stoner, J., Appel, K., & House, J. J. (2007). The first field experience: Perspectives of preservice and cooperating teachers. Teacher Education and Special Education, 30(4), 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olango, M. (2016). Mathematics anxiety factors as predictors of mathematics self-efficacy and achievement among freshmen science and engineering students. African Education Research Journal, 4(3), 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, A. M., & Stoehr, K. J. (2019). From numbers to narratives: Preservice teachers’ experiences with mathematics anxiety and mathematics teaching anxiety. School Science and Mathematics, 119(2), 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2016). PISA 2015 results (Volume I): Excellence and equity in education. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peker, M., & Ertekin, E. (2011). The relationship between mathematics teaching anxiety and mathematics anxiety. The New Educational Review, 23(1), 213–226. [Google Scholar]