Mapping Pathways to Inclusive Music Education: Using UDL Principles to Support Primary Teachers and Their Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- How can Universal Design for Learning principles identify classroom barriers to integrating music as reported by teachers?

- Can a UDL structured music teaching resource be developed using proactive and intentional design criteria, addressing teacher hesitancy in engaging with music in the classroom?

3. Methodology

4. Findings

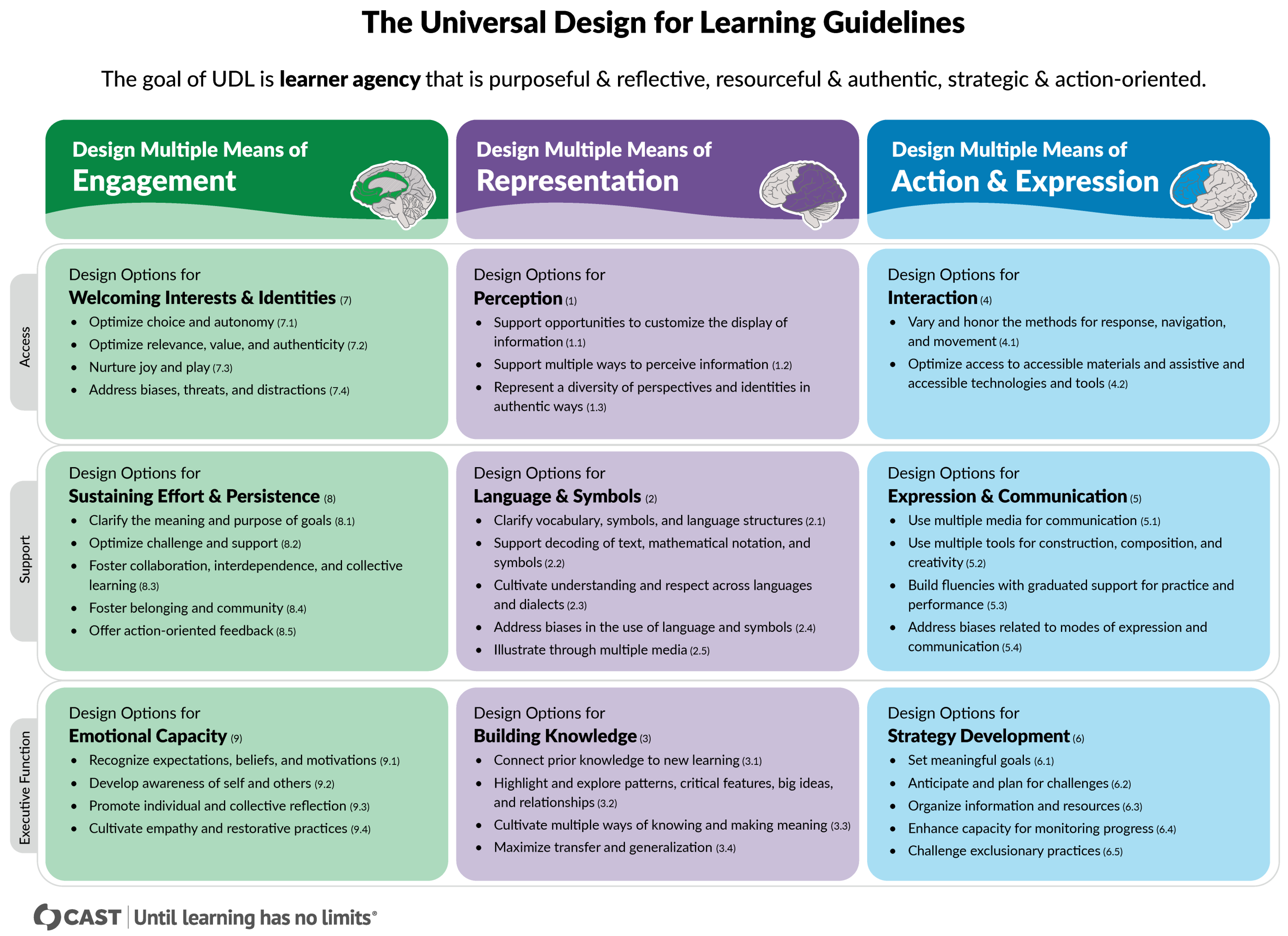

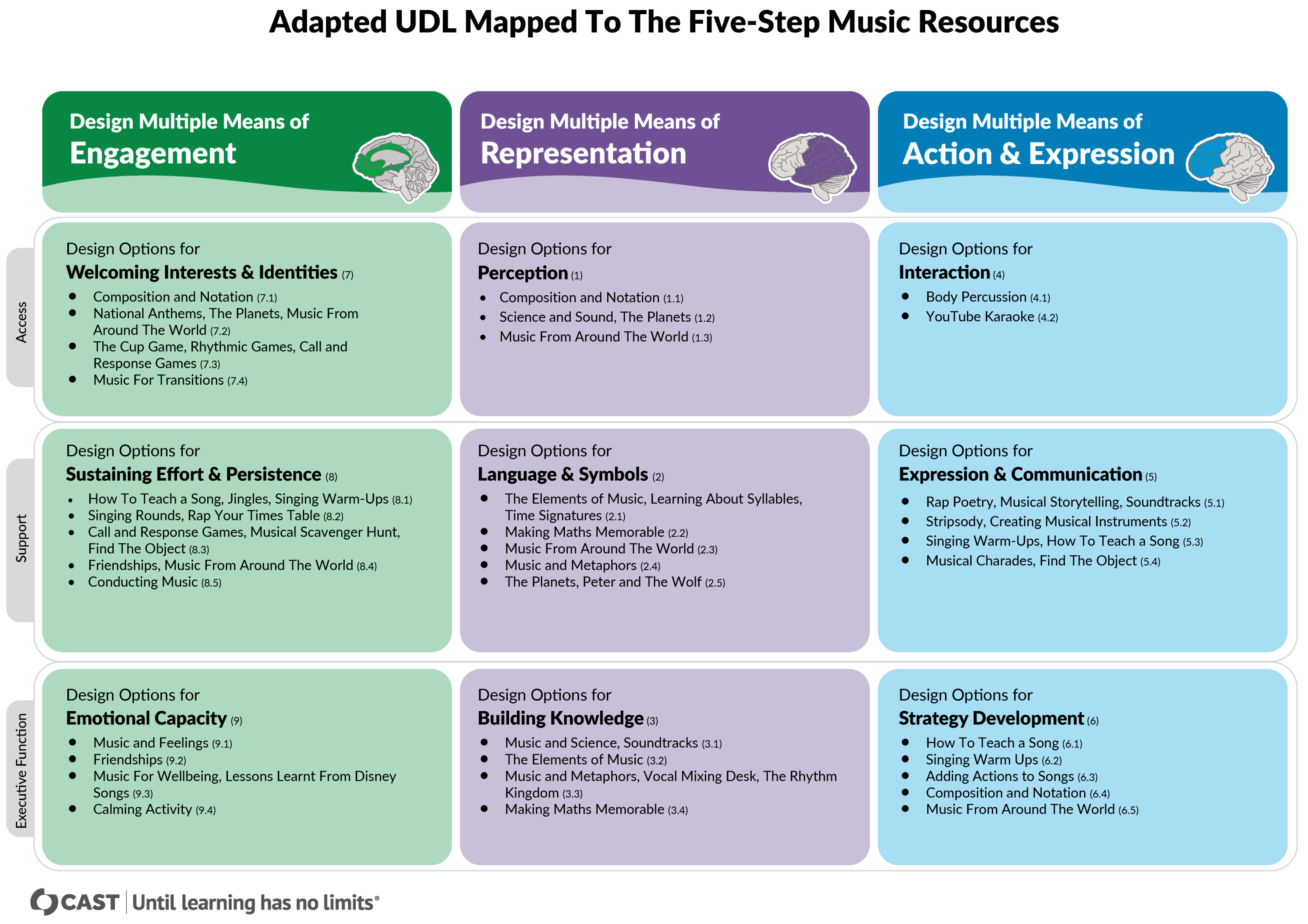

4.1. Multiple Means of Engagement

4.1.1. Teacher Barriers

I was very scared to make a mistake. And then, if I did, he was like, “this is so easy, you should be picking this up perfectly”. And I just couldn’t wrap my head around it. So I just said, “Okay, now, I don’t want to do anymore”.[Sophie]

4.1.2. Classroom Possibilities

4.2. Multiple Means of Representation

4.2.1. Teacher Barriers

If I’m an engineer, I would have knowledge in science and all of that. But the basic knowledge we’d all have, by music, it feels like unless you have actual knowledge, then you can’t really teach it.[Layla]

4.2.2. Classroom Possibilities

She does not use a musical instrument but she whenever she has an instruction that she really wants the kids to follow she [sings] it in a musical tone… “tap tap tap and make it flat”. And I was so …. so many of them were just mumbling to themselves whispering to themselves “tap tap tap and make it flat” while doing their work”[Zara]

4.3. Multiple Means of Action and Expression

4.3.1. Teacher Barriers

Towards the higher years, I think students don’t respond to it as naturally, and I think they actually might be a bit more awkward. They might feel awkward themselves trying to repeat or have it incorporated into their lesson.[Louise]

4.3.2. Classroom Possibilities

5. Discussion

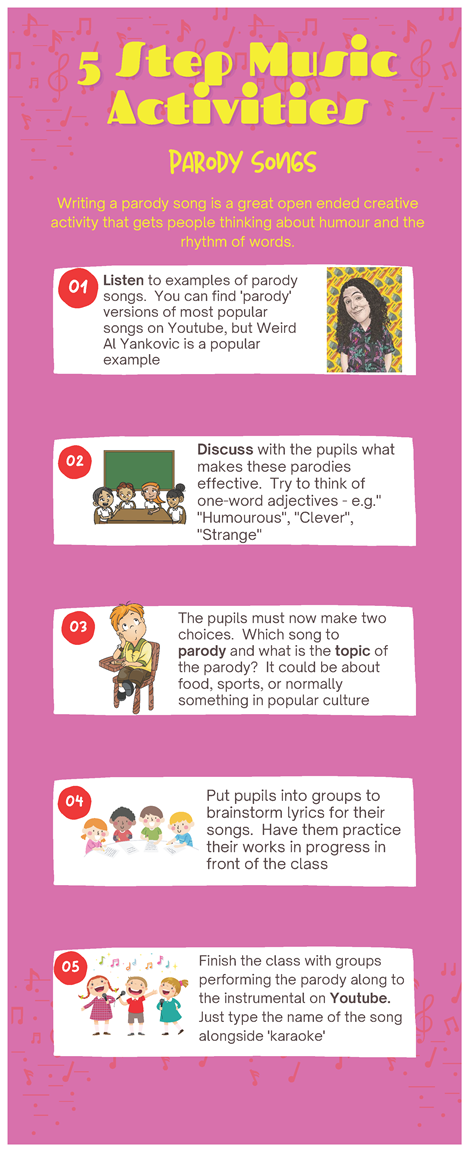

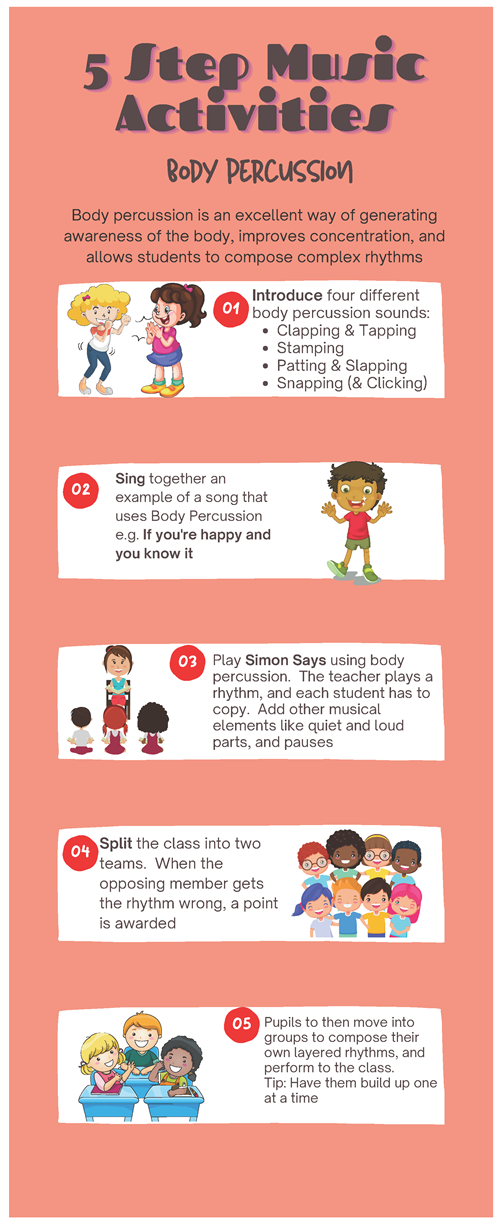

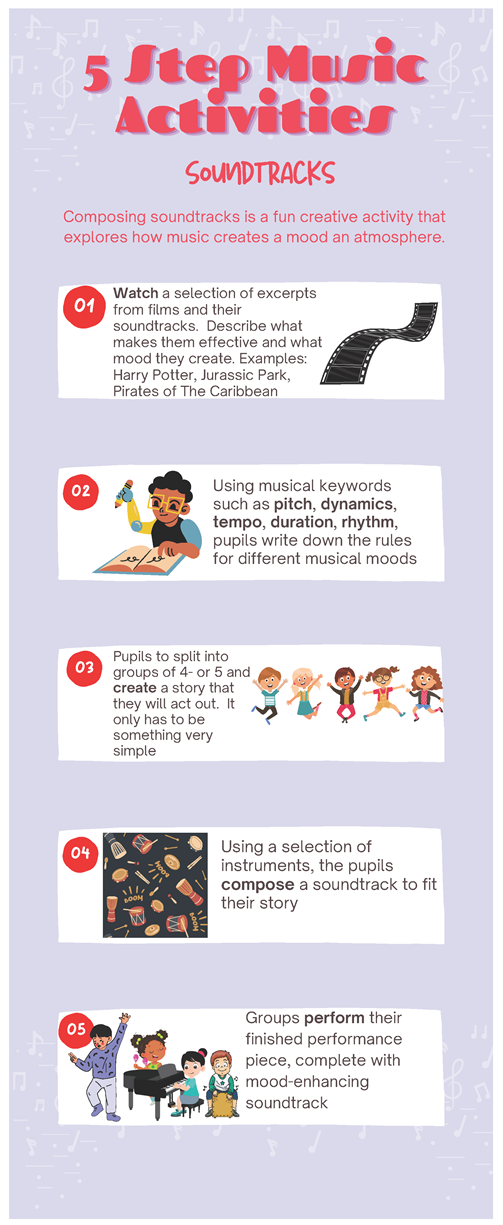

5.1. Five-Step Music Resources

- Step 1: Music Exposure

- Step 2: Music Discussion and Analysis

- Step 3: Creative Task

- Step 4: Practical Application

- Step 5: Task Consolidation

5.2. Implications and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UDL | Universal Design for Learning |

| UAE | United Arab Emirates |

Appendix A

References

- Anderson, P. J. (2025). Perceptions of musicality and musical confidence among the UAE’s trainee primary teachers: Identity formation in an international setting. International Journal of Music Education. (In Press).

- Armes, J. W., Harry, A. G., & Grimsby, R. (2022). Implementing universal design principles in music teaching. Music Educators Journal, 109(1), 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A. P., Bonin, D., Pethrick, H., Antwi-Nsiah, A., & Matterson, B. (2020). Hacking, disability, and music education. International Journal of Music Education, 38(4), 657–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BERA, B. E. R. A. (2024). Ethical guidelines for educational research, fifth edition. Available online: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-fifth-edition-2024-online (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Biasutti, M., Hennessy, S., & de Vugt-Jansen, E. (2015). Confidence development in non-music specialist trainee primary teachers after an intensive programme. Article in British Journal of Music Education, 32(2), 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 9(1), 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresler, L. (1998). The genre of school music and its shaping by Meso, Micro, and Macro contexts. Research Studies in Music Education, 11(1), 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burron, G., & Pegg, J. (2021). Elementary pre-service teachers’ search, evaluation, and selection of online science education resources. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 30(4), 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. (1997). Excitable speech: A politics of the performative. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, H., Whewell, E., Bracey, P., Heaton, R., Crawford, H., & Shelley, C. (2021). Teaching on insecure foundations? Pre-service teachers in England’s perceptions of the wider curriculum subjects in primary schools. Cambridge Journal of Education, 51(2), 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capp, M. J. (2017). The effectiveness of universal design for learning: A meta-analysis of literature between 2013 and 2016. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(8), 791–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAST. (2024). The UDL guidelines. CAST. Available online: https://udlguidelines.cast.org/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Cook, S. C., & Rao, K. (2018). Systematically applying UDL to effective practices for students with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 41(3), 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrow, A.-A. (2016). Applying the principles of universal design for learning in general music. In C. R. Abril, & B. M. Gault (Eds.), Teaching general music (pp. 308–326). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, P. (2013). Generalist teachers’ self-efficacy in primary school music teaching. Music Education Research, 15(4), 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, A. R. (2024). Disrupting ableism in music education through preservice preparation. In M. Haning, J. S. Prendergast, & B. N. Weidner (Eds.), Points of disruption in the music education curriculum (1st ed., Vol. 1, pp. 51–66). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edrabia. (2025). List of 196 best British schools in UAE. Available online: https://www.edarabia.com/schools/curr/british/in/uae/ (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Ertmer, P. A., & Newby, T. J. (1996). The expert learner: Strategic, self-regulated, and reflective. Instructional Science, 24(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, H. (1987). The theory of multiple intelligences. Annals of Dyslexia, 37, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, B. (2019). Confronting the challenge: The impact of whole-school primary music on generalist teachers’ motivation and engagement. Research Studies in Music Education, 41(2), 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gäng-Pacifico, D., & Rusconi, L. (2024). Translation and transcultural adaptation of the universal design for learning observation measurement tool (UDL-OMT). Education Sciences, 14(11), 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, D., Meyer, A., & Rose, D. (2013). Universal design for learning and the arts. Harvard Educational Review, 83(1), 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOV.UK. (2025). British schools overseas: Accredited schools inspection reports. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/british-schools-overseas-inspection-reports/british-schools-overseas-accredited-schools-inspection-reports (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Hallam, S. (2010). The power of music: Its impact on the intellectual, social and personal development of children and young people. International Journal of Music Education, 28(3), 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallam, S., & Prince, V. (2003). Conceptions of musical ability. Research Studies in Music Education, 20(1), 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, J. (2017). How musical are primary generalist student teachers? Music Education Research, 19(4), 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, S. (2000). Overcoming the red-feeling: The development of confidence to teach music in primary school amongst student teachers. British Journal of Music Education, 17(2), 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogle, L. A. (2021). Fostering singing agency through emotional differentiation in an inclusive singing environment. Research Studies in Music Education, 43(2), 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, H., & Button, S. (2006). The teaching of music in the primary school by the non-music specialist. British Journal of Music Education, 23(1), 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, K. H. (2017). The importance of handwriting experience on the development of the literate brain. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26(6), 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joswick, C., Skultety, L., & Olsen, A. A. (2023). Mathematics, learning disabilities, and learning styles: A review of perspectives published by the national council of teachers of mathematics. Education Sciences, 13(10), 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KHDA. (2016). United Arab Emirates school inspection framework. Available online: https://web.khda.gov.ae/getattachment/25c64451-95ea-43c6-b6c3-6942eb7d7182/20170112135640_KHDAINSPECTIONFRAMEWORKEN.pdf.aspx (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- KHDA. (2017). Dubai inclusive education policy framework. Knowledge and Human Development Authority. Available online: https://www.khda.gov.ae/cms/webparts/texteditor/documents/Education_Policy_En.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- King-Sears, M. E., Stefanidis, A., Evmenova, A. S., Rao, K., Mergen, R. L., Owen, L. S., & Strimel, M. M. (2023). Achievement of learners receiving UDL instruction: A meta-analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 122, 103956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.-H., & Xiong, X. (2025). Pre-service kindergarten teachers’ confidence and beliefs in music education: A study in the Chinese context. Education Sciences, 15(6), 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen, A., Österlind, E., & Viirret, T. L. (2020). Drama in education for sustainability: Becoming connected through embodiment. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 21(19), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levstek, M., Elliott, D., & Banerjee, R. (2023). Music always helps: Associations of music subject choices with academic achievement in secondary education. British Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 385–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGregor, E. H. (2024). Characterizing musical vulnerability: Toward a typology of receptivity and susceptibility in the secondary music classroom. Research Studies in Music Education, 46(1), 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J. (1995). Primary student teachers as Musicians. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, 122–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. (2017). United Arab Emirates school inspection framework. Available online: https://www.moe.gov.ae/ar/importantlinks/inspection/publishingimages/frameworkbooken.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Munroe, A. (2015). Curriculum integration in the general music classroom. General Music Today, 29(1), 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, K., Deadern, K. N., & West, R. (2016). A survey of the music integration practices of north dakota elementary classroom teachers. National Association for Music Education, 35(1), 351–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palkki, J. (2022). “It just fills you up”: The culture of monthly community singing events in one American city. Research Studies in Music Education, 44(3), 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K., Ok, M. W., Smith, S. J., Evmenova, A. S., & Edyburn, D. (2020). Validation of the UDL reporting Criteria with extant UDL research. Remedial and Special Education, 41(4), 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J., & Spencer, L. (1994). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In A. Bryman, & R. Burgess (Eds.), Analyzing qualitative data (pp. 305–329). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, A. H. (2013). Arts integration and the success of disadvantaged students: A research evaluation. Arts Education Policy Review, 114(4), 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, G. L. (2016). The music of the spheres: Cross-curricular perspectives on music and science. Music Educators Journal, 103(1), 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell-Bowie, D. (2010). A ten year follow-up investigation of preservice generalist primary teachers’ background and confidence in teaching music. Australian Journal of Music Education, (2), 76–86. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, A., Ledezma, C., & Font, V. (2025). A proposal of integration of universal design for learning and didactic suitability criteria. Education Sciences, 15(7), 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, F., & Biasutti, M. (2008). Non-music specialist trainee primary school teachers’ confidence in teaching music in the classroom. Music Education Research, 10(3), 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sircar, N. (2025). Some UAE schools consider offering higher pay to attract more male teachers. Available online: https://www.khaleejtimes.com/uae/education/how-uae-schools-hire-male-teachers (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Sirek, D., & Sefton, T. G. (2024). Becoming the music teacher: Stories of generalist teaching and teacher education in music. International Journal of Music Education, 42(2), 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, R. (2019). Evidence-based practices for music instruction and assessment for PreK–12 students with autism spectrum disorder. In T. S. Brophy (Ed.), The oxford handbook of assessment policy and practice in music education (Vol. 2, pp. 788–826). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R., & Arnold, A. (2011). The A+ Schools: A new look at curriculum integration. Visual Arts Research, 37(1), 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2024). UNESCO framework for culture and Arts education. UNESCO. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/sites/default/files/medias/fichiers/2024/04/WCCAE_UNESCO%20Framework_EN_CLT-EDWCCAE20241.pdf?hub=86510 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Verdine, B. N., Golinkoff, R. M., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Newcombe, N. S., Filipowicz, A. T., & Chang, A. (2014). Deconstructing building blocks: Preschoolers’ spatial assembly performance relates to early mathematical skills. Child Development, 85(3), 1062–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viladot, L., Hilton, C., Casals, A., Saunders, J., Carrillo, C., Henley, J., González-Martín, C., Prat, M., & Welch, G. (2018). The integration of music and mathematics education in Catalonia and England: Perspectives on theory and practice. Music Education Research, 20(1), 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitoller, F. R., & King-Thorius, K. A. (2016). Cross-pollinating culturally sustaining pedagogy and universal design for learning: Toward an inclusive pedagogy that accounts for dis/ability. Harvard Educational Review, 86(3), 366–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S., James, S., James, K., Brown, C., Kokotsaki, D., & Wigham, J. (2023). The benefits of music workshop participation for pupils’ wellbeing and social capital: The In2 music project evaluation. Arts Education Policy Review, 124, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, G. F., & Henley, J. (2014). Addressing the challenges of teaching music by generalist primary school teachers. Revista Da ABEM, 22(32), 12–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., Carter, R. A., & Hoekstra, N. J. (2024). A critical analysis of universal design for learning in the U.S. federal education law. Policy Futures in Education, 22(4), 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name (Pseudonym) | Undergraduate Degree | Instrument | Country of Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Layla | Engineering | None | UAE/Tanzania |

| Maya | Biotechnology | None | India |

| Huda | Science | Piano | UK |

| Sophie | Investment | Guitar | UAE/UK |

| Zara | Finance | None | Pakistan/Dubai |

| Emma | Physiotherapy | None | UAE/UK |

| Thandi | Finance | None | South Africa |

| Aisha | Textile Designing | None | Pakistan |

| Grace | Accounting | None | UK |

| Louise | MA Comparative Ed | None | UK |

| Step | Goal | UDL connection |

|---|---|---|

| Expose students and teachers to music through concrete tasks requiring minimal musical expertise | Principle: Multiple Means of Engagement Guidelines: 7.2 (Optimise relevance and authenticity) Checkpoints: Welcoming interests & identities |

| Use guided prompts to build musical vocabulary and analytical frameworks | Principle: Multiple Means of Representation Guidelines: 2.1 (Clarify vocabulary and symbols) Checkpoints: Language & symbols, building knowledge |

| Scaffold creative opportunities with clear parameters and manageable choices | Principle: Multiple Means of Action & Expression Guidelines: 5.2 (Multiple tools for construction), 7.1 (Optimise choice and autonomy) Checkpoints: Supported engagement, expression & communication |

| Provide explicit guidance for low-risk classroom performance and application | Principle: Multiple Means of Action & Expression Guidelines: 5.3 (Build fluencies with graduated support) Checkpoints: Strategy development, interaction |

| Encourage metacognitive processing, adaptation, and teacher ownership of pedagogy | Principle: Multiple Means of Engagement Guidelines: 9.3 (Promote reflection), 5.2 (Multiple tools for creativity) Checkpoints: Executive function, emotional capacity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anderson, P.J.; Benson, S.K. Mapping Pathways to Inclusive Music Education: Using UDL Principles to Support Primary Teachers and Their Students. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091200

Anderson PJ, Benson SK. Mapping Pathways to Inclusive Music Education: Using UDL Principles to Support Primary Teachers and Their Students. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091200

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnderson, Philip John, and Sarah K. Benson. 2025. "Mapping Pathways to Inclusive Music Education: Using UDL Principles to Support Primary Teachers and Their Students" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091200

APA StyleAnderson, P. J., & Benson, S. K. (2025). Mapping Pathways to Inclusive Music Education: Using UDL Principles to Support Primary Teachers and Their Students. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091200