1. Introduction and Background

Internationalization has long been an integral aspect of higher education, encompassing various concepts such as internationalization, comprehensive internationalization, curriculum internationalization, internationalization at home, and internationalization abroad (

Beelen & Jones, 2015). In this article, we focus on two key concepts, internationalization and internationalization at home (IaH), because this international program includes study abroad opportunities for international students, as well as IaH initiatives for Norwegian students. We adopt

de Wit et al.’s (

2015) definition of internationalization as “the

intentional process of integrating an international, intercultural or global dimension into the purpose, functions and delivery of post-secondary education,

in order to enhance the quality of education and research for all students and staff, and to make a meaningful contribution to society1” (p. 9). Additionally, we incorporate

Beelen and Jones’s (

2015) definition of IaH, which describes it as “the purposeful integration of international and intercultural dimensions into the formal and informal curriculum for all students within domestic learning environments” (p. 69). From de Wit et al.’s definition, it is clear that the goals of internationalization are to improve the quality of education and research and to make a significant contribution to society.

Over the past few decades, internationalization has emerged as a prominent focus in education policy in Norway, reflecting a broader global trend. In White Paper No. 14 (2008–2009), titled “The Internationalization of Education in Norway”, it is stated as an explicit goal to increase student mobility both within and outside the country. Additionally, it stresses the importance of IaH. “Internationalisation at home, therefore, means developing the provision of better and more internationally oriented education in Norway, and one in which foreign students are made a natural and integrated part of the international campus” (

Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research, 2009, p. 13). It further states in the Norwegian version that the internationalization of education is not merely viewed as an objective in its own right; rather, it serves as a vital means to enhance the quality and relevance of Norwegian education

2 (

Det Kongelige Kunnskapsdepartment, 2009). Additionally, it emphasizes that “The internationalisation of education should add more relevance in terms of the needs of working life and society through developing courses and programmes. The education provided should lay the foundation for our ability to meet the challenges and opportunities that arise from globalization and increased international interaction” (

Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research, 2009, p. 3). This paper examines an international program developed in accordance with the aims and framework of the aforementioned policy, which provides internationally oriented teacher education to promote student teachers’ professional development and admits both domestic and international students.

It has long been recognized that internationalization benefits communities at home and abroad, as well as society in its broadest sense, by bringing the global to the local or the local to the global (

Jones et al., 2021;

Moorhouse & Harfitt, 2021). A wealth of literature has documented the linguistic and intercultural gains of study abroad programs. Research also indicates that such experiences benefit participants’ general maturity and independence, enabling them to reflect more on their strengths and weaknesses, build their confidence, and develop a stronger sense of self (

Tang & Choi, 2004).

International programs for teacher education gained popularity in the 1980s. Their goals align closely with initiatives in other disciplines aimed at enhancing the quality of teacher education. There are a few studies on the international experiences of preservice teachers and teachers. Corroborating the findings of study abroad programs in other disciplines, scholars have reported personal growth, a broadened global view, and significant gains among student teachers (e.g.,

Barkhuizen & Feryok, 2006;

Gleeson & Tait, 2012;

Holmarsdottir et al., 2023;

Tang & Choi, 2004;

Ward & Ward, 2003;

Willard-Holt, 2001). Besides the typical gains, studies have also demonstrated that student teachers gain professional competence.

Lee (

2011) found that an international placement equipped Hong Kong student teachers with teaching skills, strategies, and competences. It was also found that student teachers had an enhanced interest in teaching English (

Lee, 2011).

Black and Cutler (

1997) and

Faulconer (

2003) found, in their studies on student teachers’ practicums in Mexican schools, that participants demonstrated more empathy for those in a new culture, eliminated some cultural biases, and became more resourceful and flexible. Other similar studies indicated that preservice teachers were more able to compare and contrast different education systems (

Clement & Outlaw, 2002;

Holmarsdottir et al., 2023).

Williams and Grierson (

2016) emphasize that international teaching practicums offer rich and varied learning opportunities for all stakeholders involved—including teacher candidates, teacher educators, and members of the host community. Carefully orchestrated international programs, as part of teachers’ professional preparation, have the potential to foster specific intercultural competencies (

Back et al., 2021;

Smolcic & Katunich, 2017). They were also more active in problem-posing and experimentation with alternative solutions in the classroom (

Moorhouse & Harfitt, 2021;

Vall & Tennison, 1992).

Sahin’s (

2008) study reported that teachers’ experiences abroad not only aided the development of a global perspective but also helped to strengthen their teaching abilities.

In summary, previous research on international programs offers valuable insights into the benefits of these programs. However, little literature discusses how the different components of these programs have contributed to the development of participating students from the perspective of insiders. There is even less research on international programs that recruit both international and local students. This article aims to bridge these gaps by providing insider perspectives that demonstrate how the various components of an international program contribute to the educational goal of cultivating the professional development of both international and local student teachers. Biesta challenges educators, policymakers, and stakeholders to reexamine the overarching goals of education and advocate for a balanced approach to the three functions of education—qualification, socialization, and subjectification. He calls for an educational system that prioritizes not only vocational training but also the development of democratic citizens who actively engage with their communities. Internationalization, as an aspect of education, serves the same overarching goals. Consequently, this article is grounded in Biesta’s three functions of education and the objectives of teacher education. “Insider perspectives” refer to the views of the program participants. The article also aims to serve as a formative assessment of this program, facilitating further improvement, as well as inspiration for others developing international programs in Norway and beyond. Thus, this study foregrounds the perspectives of student teachers and addresses the following research question: How do international and local students perceive and experience the contributions of various components of an international teacher education program to their professional development?

2. Setting the Scene: About the Program

Being outdoors and engaging in outdoor activities is a common part of daily life and pedagogical practice in Norwegian kindergartens. It is written in the national Framework Plan for Kindergartens that “children shall be given outdoor experiences and discover the diversity of the natural world, and kindergartens shall help the children to feel connectedness with nature” (

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2017, p. 11). Therefore, the topic of outdoor education is integrated into early childhood education in Norway.

Early childhood teacher education in Norway is designed to equip educators to work with children from birth to age six. It typically spans three years in a tertiary institution and culminates in a bachelor’s degree. A typical curriculum encompasses a range of subjects, including child development, pedagogy, play and learning, language acquisition, and the significance of outdoor education. Students also delve into topics such as diversity, inclusion, and ethical considerations in education. As part of their training, student teachers are required to complete a 100-day internship in a kindergarten, where they can apply their theoretical knowledge in a real-world context.

The program is an elective program offered in English to international and Norwegian student teachers by a Norwegian university. The primary objective of this interdisciplinary program is to equip participating student teachers with essential knowledge and skills in esthetic and outdoor activities, fostering an understanding of the connection between culture, nature, and outdoor experiences. This foundation will enable them to apply these insights effectively in their future teaching practices. In this program, students receive instruction from specialized subject teachers while engaging in interdisciplinary activities that empower them to design pedagogical approaches incorporating various learning areas, particularly esthetics, mathematics, and outdoor education. Additionally, a crucial aspect of the program is to enhance student teachers’ understanding of children’s play and to integrate play-based learning initiatives into their teaching methods, allowing for a child-centered approach.

This interdisciplinary program encompasses four academic subjects, namely esthetics, outdoor education, mathematics, and pedagogy. The required program literature is listed in the program description and should be read before the lectures. Student teachers are encouraged to use the literature in classroom discussions, writing assignments, and oral exams. Let us take pedagogy as an example. Gert Biesta’s book, Good Education in an Age of Measurement: Ethics, Politics, Democracy, is listed in the course literature. As a compulsory group assessment, students are required to engage in a discussion on a contemporary educational challenge, drawing on relevant content from the aforementioned book and subsequently submitting a written synthesis of their discussion.

Inspired by the work of John Dewey (1859–1952), who articulated his vision of the ideal teacher in his pedagogic creeds as early as 1897, student teachers in this program are required to write their pedagogic creeds. This reflective exercise encourages them to articulate what they consider essential to their future professional identities as teachers. The Norwegian Framework Plan for Kindergartens (

Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, 2017) serves as a foundational reference throughout the program, particularly within the pedagogy component, shaping both the content and pedagogical orientation.

Field experiences are another important component of the program. The term “field experiences” refers to two distinct types of experiences. The first is outdoor practices during the teaching period. They offer a variety of outdoor activities with distinct purposes. Some aim to offer students opportunities to become familiar with each other and Norwegian outdoor experiences as locals, while others allow students to implement their planned outdoor activities with the children. Additionally, students participate in a mandatory three-day excursion, which includes a two-night stay in a cabin located approximately 1200 m above sea level. There, they engage in various outdoor snow activities alongside their classmates. The second set of experiences is a two-week internship at a local kindergarten. During these two weeks, the students will participate in daily indoor and outdoor activities with children aged one to six under the guidance of an experienced teacher. Student teachers are required to use the approaches that they have learned in the classroom to document their daily observations of their interactions with children. The documentation, serving as a reflective record, will be submitted to their mentors, providing a reference for them to guide and supervise. The supervision lasts 90 min and takes place once a week. Subject teachers visit the kindergartens to engage in discussions with both student teachers and their mentors. All student teachers need to lead or organize an “outdoor art project” with the children. Additionally, Norwegian student teachers are required to have two leadership days during the internship, where they take on the responsibility for planning, organizing, and determining the content of these days, in collaboration with the staff. Due to the language issue, this requirement is optional for international students. Some choose to fulfil it.

3. Theoretical Framework

Building on

Kennedy’s (

2014) insights, we begin our theoretical framework with Biesta’s conception of the purpose of education, followed by its alignment with the purposes of teacher education. This theoretical framework serves as the foundation for our data analysis and subsequent discussion.

3.1. Biesta’s Purpose of Education

According to

Biesta (

2021), contemporary educational policy often overlooks the teaching profession and the crucial role that teachers play in promoting student learning and well-being. He argues that teaching should not merely serve as a means of producing measurable learning outcomes; instead, it should highlight the intrinsic value that it provides to students. Biesta challenges educators, policymakers, and stakeholders to reexamine the overarching goals of education. By advocating for a balanced approach to the three functions of education—qualification, socialization, and subjectification—he calls for an educational system that prioritizes not only vocational training but also the development of democratic citizens who actively engage with their communities. His insights promote a holistic understanding of education, recognizing its vital role in shaping individuals who are competent, socially aware, and self-determined.

This study draws on Biesta’s conceptualization of the three functions of education—qualification, socialization, and subjectification—as articulated in his works (2010, 2013, 2021). This framework serves as a central theoretical lens.

According to

Biesta (

2010), qualification is linked to the acquisition of knowledge, skills, understanding, dispositions, and forms of judgment that enable learners to perform specific actions. The qualification function is undoubtedly one of the most significant functions of organized education (

Biesta, 2010, p. 20). Socialization is the process by which individuals become part of a particular social, cultural, and political order, which educational institutions sometimes actively promote in transmitting specific norms and values. On the other hand, subjectification refers to the process of becoming a subject or the subjectivity of the educated. Subjectification can also be understood as the opposite of socialization, as it is about ways of being independent from orders and ways of being in which the individual is not simply a “specimen”; it is about unique and qualified freedom, where freedom is integrally linked to our existence as a subject (

Biesta, 2010,

2021).

Biesta (

2010) argues that, while it is helpful to distinguish among the three dimensions of education, it is equally important to acknowledge their inherent overlap, interconnection, and contradiction. He further contends that meaningful educational practice should strive to engage with all three dimensions simultaneously.

In this article, we link qualification to student teachers’ understanding of child development and various knowledge areas, enabling them to design activities that enhance children’s learning and development. We also explore how education in university settings and field experiences fosters socialization, integrating student teachers into the early childhood education and care profession. Additionally, we examine subjectification, focusing on student teachers’ abilities to make sound, professional, independent, and ethical judgments in response to the situations that they encounter during their field experiences and in their future careers.

3.2. The Purpose of Teacher Education and Biesta

This section outlines the purpose of teacher education and examines it through Biesta’s theory of educational purposes, which informs the subsequent data analysis and presentation of the findings.

The national curriculum plan published by the Norwegian government (

Regjeringen, 2006) stipulates that teacher education programs should be structured around five core areas of professional competence. These competencies align closely with international frameworks (e.g.,

Bransford et al., 2005;

UNESCO & International Task Force on Teachers for Education 2030, 2019). These five areas are (1) subject competence—a deep understanding of the disciplinary content, theories, and methodologies, as well as knowledge of children, childhood, and child education and knowledge of theories and working methods in and across subjects; (2) didactic competence—the ability to analyze curricula and reflect over content and working methods and make provisions for learning and development processes for all pupils; (3) social competence—the ability to observe, listen, understand, and respect the views and actions of others; the ability to cooperate with pupils, colleagues, and parents and guardians; and the ability to function as a leader in a community of learners; (4) adaptive and developmental competence—the capacity to assess one’s own activities and those of the school, contribute to development of the teaching profession, take part in local development work, and strengthen one’s own competences; and (5) professional ethics competence—insight into one’s own attitudes and the ethical challenges of the profession and the ability to assess learning situations in light of fundamental educational values (

Regjeringen, 2006, p. 7). These five areas of competence to be cultivated in future teachers can be interpreted as reflecting Biesta’s theoretical framework concerning the purposes of education. Specifically, subject and didactic competence correspond to the purpose of qualification, while social, adaptive, and developmental competences align with the purposes of socialization and professional ethics, which in turn relate to subjectification.

4. Materials and Methods

This article is based on a research project titled Participating Student Teachers’ Perspectives on an International Program and Their Professional Development. The project aims to identify good practices and areas for improvement in the international program offered at a Norwegian university. The project employs a qualitative research method to systematically represent the experiences of participating student teachers in the international program, identifying categories of meanings and experiences (

Austin & Sutton, 2014).

4.1. Participants

The informants in this study are student teachers who participated in the aforementioned international program at a university in Western Norway across four cohorts: 2019, 2021, 2022, and 2024.

Table 1 presents an overview of program enrolment and the study informants.

International student teachers are from a diverse range of countries. The informants in these three cohorts are primarily from European countries, including Germany, Spain, Italy, Slovenia, and the Netherlands. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the class roster also featured students from universities in China, who are expected to return in the upcoming academic year. They are student teachers who will work in kindergarten, primary education, higher education, or special education. Norwegian student teachers are enrolled in early childhood teacher education and will work as kindergarten teachers after graduation.

4.2. Data and Data Analysis

The primary data are the program participants’ narratives, written in the form of their pedagogic creeds. In total, 50 pedagogic creeds were collected and analyzed. Writing an individual pedagogic creed is a compulsory assignment for participating student teachers. After the assignments were evaluated, participants received an information letter based on the template provided by the Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research (SIKT), and they were asked to consent to the use of their pedagogical creeds for research purposes. In total, 50 student teachers provided their agreement. Additionally, we obtained ethical approval from SIKT and received confirmation that we could proceed with our study. The pedagogic creed encompasses the subjective perceptions, attitudes, values, and emotions that are intertwined with the professional experiences of student teachers in the field of education. At the same time, students were asked to reflect on how their experiences in the program, such as their inspiration from the field experiences, lectures, and the literature that they had read, contributed to their professional development as future teachers, which provided us with data to explore how the program components facilitated their professional development. Additionally, three focus group interviews with 11 students from the 2021 cohort were conducted to supplement and triangulate the findings. The focus group interviews were voluntary and not audio-recorded. The second author was present in the interviews and took notes of the them, which were later checked by the first author, who led the interviews.

The quotations used to support the findings were selected from informants’ narratives through consensus among the three authors. The original language was retained, despite some minor errors, to preserve its authenticity. To ensure confidentiality, each informant was coded with a unique identifier, including the cohort year and an indication of where they were from. For example, 19N-1 denotes a Norwegian student of the 2019 cohort, while 22I-1 denotes an international student from the 2022 cohort. Interviewees were given codes indicating the cohort year, where they were from, the data source (Inv), and an alphabetical symbol. For example, 21I-InvA denotes an international student teacher, and 21N-InvA refers to a Norwegian student teacher.

The data were analyzed deductively, guided by the overarching purpose of teacher education and Biesta’s three functions of education.

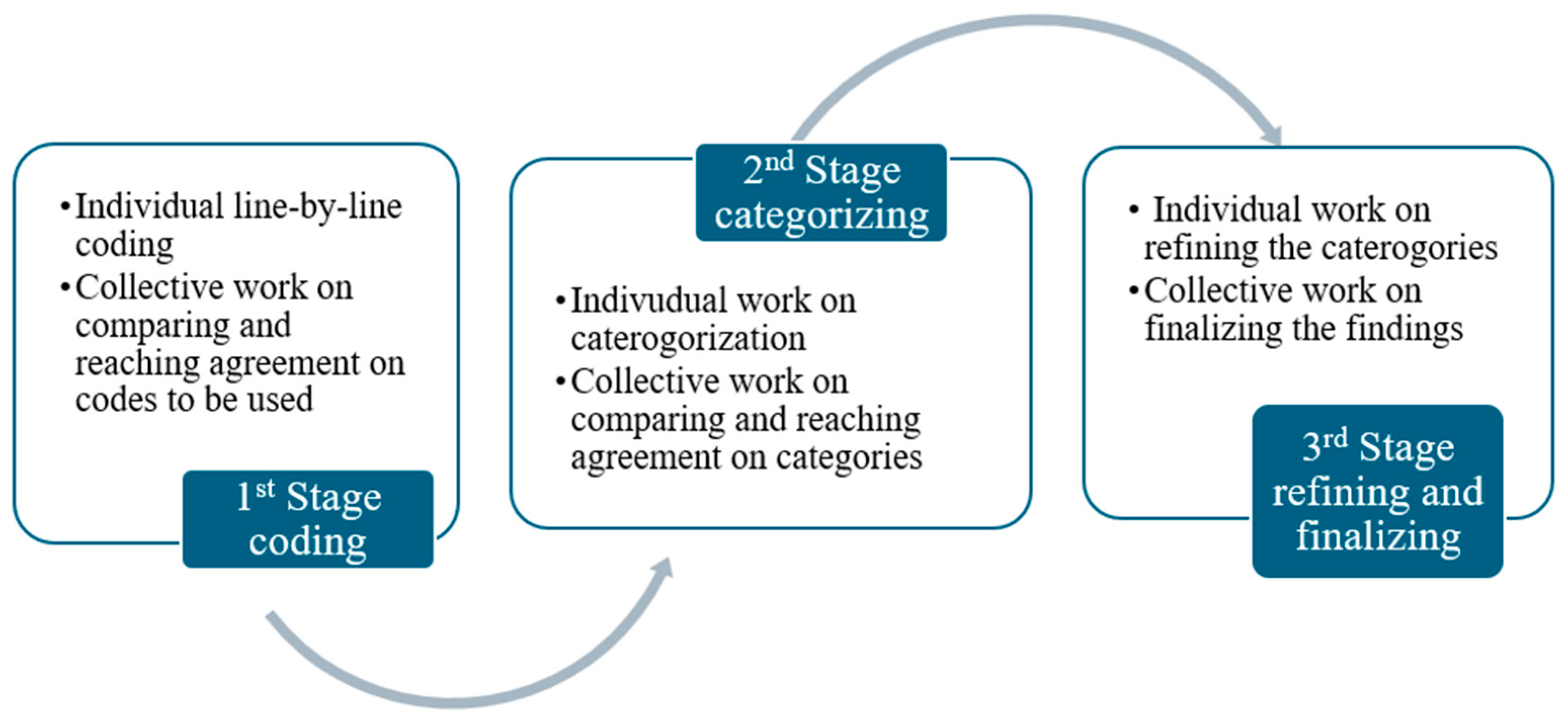

Figure 1 below depicts the sequence of the analysis.

The analysis comprised three stages, each involving several iterations conducted initially by each author individually, followed by collaborative efforts among all three authors. Throughout the analysis, the authors employed a hermeneutic circle, and hermeneutic conversations were conducted. The three authors found common languages (codes and categories) among the different narratives through the hermeneutic conversations. The students’ narratives were interpreted in terms of their individual experiences. These individual experiences were also integrated to present a complete landscape of collective experiences (

Bontekoe, 1996). Quotes that effectively captured various aspects of students’ experiences were chosen to substantiate the findings.

5. Findings

Drawing on Biesta’s functions of education and the goals of teacher education, we identified three main themes, each comprising subthemes: (1) qualification in terms of gains in subject, didactic competence, and intercultural competence; (2) socialization in terms of gains in social, adaptive, and developmental competence; and (3) subjectification in terms of gaining competence to make professional and ethical judgements. An overview of the findings is illustrated in

Figure 2.

5.1. Finding One: Gains in Subject and Didactic Competence as Qualification Outcomes

The theme of qualification encompasses three key subthemes: (1) developing subject competence, (2) acquiring didactic competence, and (3) fostering intercultural competence.

5.1.1. Developing Subject Competence

Subject competence involves familiarity with the content, theories, and methods associated with the various basic subjects; knowledge of children, childhood, and child education; and knowledge of theories and working methods in and across subjects.

Familiarizing oneself with the Norwegian Framework Plan for Kindergartens is one of the key components of the program. The influences that this Framework Plan had on the student teachers, especially international student teachers, were evident in their pedagogic creeds. While international student teachers consider incorporating components of the Norwegian Framework Plan into the curriculum guidelines of their country, Norwegian students talk about using it as a guide for their future work. The international students reflected on how the different values in the Norwegian framework had influenced them both explicitly and implicitly. They specifically noted that the Framework Plan inspired them to develop and design teaching and learning activities. One student said,

The framework plan in Norway is different if compare it with a XX

3 framework plan. We do not spend much time outside, especially not during the winter but here I learned that is important to give children opportunities to spend time in the nature and let them discover the surrounding areas.

(19I-1)

Besides the Framework Plan, some international student teachers mentioned the influence of field experiences, which enabled them to learn more about children and their learning styles. They indicated that they would incorporate the good practices that they observed in Norwegian kindergartens into their future work. One student shared,

Because the children here are a lot outside, exploring and going on trips, they move so much more, but unconsciously. I think this approach is so much better because the children learn to move a lot, just by being outside and discovering. (…) When I’m back in the XX, I want to bring this knowledge to my internship school. Normally, I just give my physical education classes and then the children leave. But I think it can make a difference to bring a part of the Norwegian lifestyle to XX. So the children are not ‘pushed’ to be exercise, but like it by themselves and see it as a way to discover the world. (…) If I make a summary about what I find the most important as a future preschool teacher is a good development of the children I teach. I want to prepare children to live their own independent lives and be healthy.

(24 I-1)

Moreover, the student teachers mentioned that staying in Norway and having a practicum in a kindergarten helped them to develop an understanding of and empathy towards children who did not speak the local language and learned how to communicate with these children. One student in the focus group interviews shared, I have learned the importance of how we can communicate with our body, which also calms myself down (21I-InvC).

5.1.2. Acquiring Didactic Competence

Didactic competence refers to the ability to analyze curricula, reflect on content and working methods, and make provisions for learning and development processes for all pupils. The student teachers referenced the literature that they were assigned to read in order to support their perspectives and opinions while composing their pedagogic creeds. They were asked to read some well-known works on education and early childhood education. The quotations in the pedagogic creeds revealed that the student teachers not only engaged with the literature but also acquired academic insights and vocabulary that helped them to articulate their thoughts and practices. For instance, Biesta was frequently cited by them.

Besides gaining inspiration about the purposes of education from the literature provided by the different subjects, the student teachers highlighted how the literature provided them with evidence to support their pedagogical choices in their future work. Some of them can now use professional vocabulary to reflect on and think about their practice. Some student teachers clarified that they had gained academic insights into aspects that they believed were important for their future teaching. One recounted,

During my internship, I have seen that play is the highest priority. I have observed how it provides countless opportunities for learning, such as how children learn to form relationships with their peers, how they are able to develop empathy at such a young age, and how they resolve conflicts by talking to each other. And it is not only with their peers; they also interact with the teachers. Here, the teachers play a lot with the children, which helps to build trust with them. In addition, it is a way for the teachers to observe the children more closely, see their behavior and skills, and identify areas that need further development.

(24I-3)

Narratives from the majority of the international student teachers highlighted that the two types of field experiences that they had led them to recognize the value of outdoor activities for children and the wider community. One student in one focus group interview said, I gain most from being outdoors and in nature. I learned to use the full potential of nature with children, by which we become more appreciative of nature (21I-InvF).

More significantly, they developed the ability to plan and execute outdoor activities through their observations and hands-on experience. For example, one student in one of the focus group interviews stated, I learned to set less rules and regulation for play and children can experiment themselves (21I-InvD).

In the introduction of her pedagogic creed, one Norwegian student emphasized that children’s participation was among the most important aspects to prioritize in her future role as a teacher, reflecting a shift in her professional perspective. She wrote,

Most of the time, I would want to include the children in the problem-solving because I want to challenge their thinking and invite them to participate through the exploratory conversation…. As a kindergarten teacher, I must be able to facilitate play that the whole group of children can participate in.

(19N-2)

Several international student teachers mentioned how they experienced joy in learning when participating in the activities in Norwegian kindergartens. This experience inspired them to reflect on how they could incorporate these activities and methods into their future professional practice. One of them shared,

Spending time outside was what I enjoyed most during my internship. I could see how resourceful the children were in a space different from the usual one, and the many ways they learned thanks to the environment around them. One very relevant thing I observed and discussed with the teacher during the internship was that children in an outdoor environment are more democratic than in a classroom. There was one child who always took toys from his classmates or hit them in the classroom, but when he went outside, he became a different child, playing with others and not fighting with anyone.

(24I-3)

5.1.3. Fostering Intercultural Competence

Intercultural competence is the capacity to communicate effectively and appropriately in intercultural contexts. In today’s increasingly globalized world, possessing intercultural competence is essential for teachers. The student teachers noted that both their interactions with classmates from diverse countries and their internships in Norwegian kindergartens contributed to their development of intercultural competence.

One student mentioned, “Through my relationships with my peers, I have learned how different cultures and ways of thinking can lead to greater academic and personal growth” (24I-4). This quotation illustrates that the students gained intercultural competence in thinking and communicating. Another Norwegian student teacher also mentioned,

Even though it was a little bit difficult for me to communicate with international student teachers in English, I enjoyed knowing how different countries educate kindergarten children and helped me to understand what to do with children from another background.

(21N-InvB)

Additionally, the student teachers, particularly international ones, noted that, during their internships, they developed empathy for children who did not speak the language used in the kindergarten, drawing from their own experiences. At the same time, they discovered that body language was an effective means of communication. One international student’s remarks were illustrative in this regard. She shared,

And also, what has been an incredible challenge for me was the communication with children, because we did not talk and share the same language, so I have to develop my body language as the way of expressing my ideas and also thoughts. This situation made me feel and put myself in the place of foreign children, what they feel and how difficult is to be understood and understand everything of their surroundings when they begin in a new kindergarten in a different country and anyone shares their language. Owing to that, I am now more conscious about the importance of using my body language as a way of communication in every dynamic, and enhance it to the children such as pointing, making so many gestures… to facilitate and help other schoolpartners to feel in a comfortable atmosphere and place, and also to understand our ideas. So my other future goal is to use body language as another way of communication and learning for every of our children. Thanks to using it as much as possible they will develop some skills that if they do not use it, they won’t, and also is a nice step to introduce them to inclusive language, so maybe in a future they will learn sign language and facilitate people to understand their surrounding.

(21I-3)

The remarks not only indicated that the student teacher had developed effective communication strategies to interact with children who spoke different languages, but also demonstrated her commitment to fostering an inclusive environment for everyone.

5.2. Finding Two: Gains in Social, Adaptive, and Developmental Competence as the Outcome of Socialization

The student teachers’ writings indicated that they had established and confirmed their professional identities as teachers, which echoes socialization. This process is reflected in two subthemes: (1) gaining social competence and (2) gaining adaptive and developmental competence.

5.2.1. Gaining Social Competence

Social competence encompasses the ability to observe, listen, understand, and respect the views and actions of others; the ability to cooperate with pupils, colleagues, parents, and guardians; and the ability to assume leadership within a community of learners. Concerning respecting and listening to children’s voices, a Norwegian student wrote,

I knew my focus would be to one day be able to participate in giving children a better childhood than I had myself. … So for me, as a future teacher, I’d say that children’s rights are essential to me and my work. My focus would be to respect the rights given to our children and treat them properly as human beings with thoughts, emotions, and opinions (…) I could not work in a place where children’s voices were silenced or overruled.

(22N-1)

Another international student teacher’s writing about her ideas on collaboration with parents indicated that she had developed competence in engaging effectively with families. She wrote,

I believe that an open dialogue both on the part of the kindergarten and on the part of the parents can have a decisive role in creating trust. (…) Another thing that is important for a child in kindergarten, is the handover between home and kindergarten, which should feel coherent for the child. Communication between parents and the kindergarten teacher is therefore again essential.

(22I-4)

5.2.2. Gaining Adaptive and Developmental Competence

Adaptive and developmental competence is about assessing one’s own activities and those of the school, contributing to the development of the teaching profession, taking part in local development work, and strengthening one’s own competence. Notably, many international students described their experiences during the overseas semester as transformative. They frequently highlighted a shift in their understanding of the roles of teachers and a deepened appreciation for the value of children’s play and outdoor learning. Almost all international participants expressed an intention to integrate, or thoughtfully adapt, these insights into their future teaching practices in their home countries.

Writing the pedagogic creed allowed the student teachers to be reflective. As it was a compulsory assignment in the subject pedagogy, all participants strongly engaged in this task. Their narratives demonstrated thoughtful and in-depth reflection on the learning outcomes of the experience, the kinds of teachers that they aspired to become, and their professional growth throughout the semester-long immersion. As one shared,

I will never stop learning and always try to develop my own competence. I have to reflect upon my pedagogic fundamental view, and always to remember to see the children as subjects and not an object as a future teacher.

(19N-12)

Concerning how the student teachers wished to bring changes to educational practices in their own countries, one student’s writing was quite representative. She wrote,

I want to prepare children to live their own independent life and be healthy. Because of the lifestyle I have seen in Norway, I want to try to make the outdoor/exercise life more common in the XX. In this way the children in the XX can grow up healthier, instead of ‘forcing’ the children 1 h of exercise they often don’t want. Outside that I want the children to explore the world, explore who they are and play/socialize with other children. My task as a teacher is to teach them how to do this.

(24I-1)

In the classroom, the dialogs between the teacher educator and the students on Biesta’s book fostered students’ critical reflection on the use of his framework to critically analyze the educational system at home, as one student wrote:

To conclude, this experience has made me reflect above all on the importance of communication in all its forms». (…) While in XX, the educational approach tends to be more rigid and focused on the acquisition of knowledge in a structured environment, here exploration and play are valued as fundamental components of learning.

(24I-7)

Furthermore, the student teachers also mentioned that the teacher educators in the program were their role models. In a focus group interview, one international student shared that they were taught to “make changes step by step-we cannot make big changes but we can change small things, e.g., more play and play outdoors, involve children more, the role of teachers is to help children to establish relationships” (21I-InvE) by the teacher educators, and they did the same for them. The teachers trusted them and helped them to develop a good classroom environment.

5.3. Finding Three: Gained Competence to Make Independent Professional Judgments as Subjectification

It was found that the participating student teachers gained the competence to make and justify professional decisions and judgments, which enabled them to become independent thinkers. In this aspect, subthemes on how to organize and dress for outdoor activities with children/students and involve the students in decision making and engage them in the activities were closely related to gaining competence to make professional ethical judgments. Field experiences had the most significant influence on them in this respect. According to the participating student teachers, the internships inspired them to approach their future teaching from a different perspective. The outdoor experiences that Norwegians experienced also inspired them.

Besides the above, professional ethics competence involves insight into one’s own attitudes and the ethical challenges of the profession, as well as the ability to assess learning situations in light of fundamental educational values. One student shared,

Another important topic is the development of autonomy and independence in such young children. I have been surprised by how autonomous children as young as 2 or 3 years old can be. I come from a country where adults are too overprotective with children. This makes them dependent and incapable of doing anything on their own. Therefore, it’s important for me to help them develop their autonomy.

(24I-2)

Furthermore, in a focus group interview, some students made it clear that they would challenge traditional practices in education in their home countries because they had witnessed how capable children could be. One student teacher said,

My views about children have changed. I’ve noticed that children here have more freedom to play and explore by themselves. I should trust children’s competence and allow them to do things independently when I become a teacher.

(21I-InvA)

6. Discussion

The structure and contents of this international program provide international and Norwegian students with encounters that contribute to their development/gains in the differing dimensions needed to succeed as future teachers. We discuss how different components of the international program promoted the development of the participating student teachers as future teachers, drawing on prior research and framed through

Biesta’s (

2010) three functions of education: qualification, socialization, and subjectification.

Corroborating the findings of previous research (e.g.,

Lee, 2011), this research also found that this international program helped the participating student teachers to gain the subject and didactic competences that they required as future teachers. This mainly resulted from reading the literature and from field experiences. It includes having the pedagogical knowledge to plan activities for children and having the skills to observe and document the children’s learning and development from a teacher’s perspective. Moreover, in line with the findings of other researchers (e.g.,

Barkhuizen & Feryok, 2006;

Faulconer, 2003), the participating student teachers gained intercultural competence, which enabled them to be more understanding towards children and parents with varied backgrounds in an increasingly diversified society. Enhancements in these areas correspond with Biesta’s function of qualification, as they equip future teachers with the knowledge and skills that are essential in being a teacher.

Consistent with the findings of other researchers (e.g.,

Faulconer, 2003;

Williams & Grierson, 2016), it has been observed that internships in a foreign culture have a profound impact on the majority of student teachers. The student teachers frequently mentioned the two-week internship as an “aha” experience for sudden new learning. During the ten-day internship in the kindergarten, many student teachers experienced significant changes in their perspectives on children, learning, and education.

Our findings indicate the important role of teacher educators. The student teachers, particularly the international ones, described how the behaviors of the teacher educators in the program were eye-opening for them. Throughout various trips and classroom lectures, the students sensed that the teachers had confidence in their abilities and entrusted them with different tasks. Socialization is about becoming part of a larger community where values, traditions, and culture influence socialization (

Biesta, 2010,

2013). In the study, students were socialized into the profession through classroom discussions and field experiences.

It is worth mentioning that the combination of international and local students facilitates the socialization process. This international program encompasses both study abroad opportunities for international students and internationalization at home (IaH) for Norwegian students. It reflects the integration of global perspectives into local contexts and vice versa (

Jones et al., 2021;

Moorhouse & Harfitt, 2021), benefiting all participants involved. This study found that international and Norwegian students gained experience in socialization with people of other cultures and knowledge about early childhood education in other countries. From this perspective, we argue that it is essential for future teachers who enter the field to be both qualified and socialized. This aligns with Biesta’s concept of qualification socialization, as it enables student teachers to learn how to navigate their roles within the community of teachers and gain knowledge of other countries’ early childhood education.

Furthermore, the findings of this study suggest that composing a pedagogic creed serves as an effective tool for student teachers to engage in reflection. The students in this international program can reflect critically on their learning processes by writing a pedagogic creed. Reflection involves examining subjective perceptions, attitudes, values, and emotions related to the student teachers’ education journeys to become professional teachers. As noted by

Broeder and Stokmans (

2012, p. 5), teachers, as reflective practitioners, play a vital role in addressing the constantly evolving multicultural and multilingual landscape. We find the pedagogic creed a valuable contribution and an important tool in developing the personal, ethical, and conscious identity needed for today’s teachers, which aligns with Biesta’s subjectification function, as it is linked to values such as freedom, participation, equality, and the experience of mastery. As seen from the presentation of our findings, the three dimensions overlap with each other rather than contradicting each other.

These findings reveal that including international and local students in an international program benefits both parties. While international students have more “aha” experiences, Norwegian students gain more academic language and knowledge of the education systems across diverse cultures. Some of the student teachers, both local and international, in one way or another, mentioned that they were mutually influenced and inspired by each other through their interactions and socialization. In addition to echoing

Clement and Outlaw’s (

2002) findings, where the student teachers were more able to compare and contrast different educational systems, they also critically reflected on what they could borrow to improve their country’s education. In this way, what they had previously taken for granted was rethought and reflected upon.

7. Final Remarks

Figure 3 below summarizes our findings, showing that the different elements of the international program allow the participating student teachers to have “aha” experiences that result in the intended outcomes.

The findings of this study corroborate much of the existing research on international programs regarding participants’ benefits, including enhancements in intercultural competence, professional knowledge, and skills, as well as the development of a professional identity. It also found that including international and local students benefited both parties. Moreover, it is important to provide student teachers with reflective tools to become critically reflective practitioners. As the findings are based on a single case study, there are certain limitations. Moreover, as the assignment was subject to evaluation by the teacher educator, the student teachers refrained from reporting negative experiences, except for minor practical issues, such as having difficulties in navigating the university’s digital platform and the wish that the program would recruit students from more countries. Nonetheless, we believe that this international program can inspire universities in Norway and beyond to offer international programs to students in higher education.

The balance of international and local students also helps to resolve the language problems and cultural challenges that international students may have in a foreign country. This is of great value, especially during the internship period, when local students can explain and interpret. We recommend that international and local students be mixed during their internships. Based on our teaching experiences from the program, we recommend increasing the number of in-person teaching sessions, which will enhance the qualification, socialization, and subjectification of the participating students.

We especially recommend that student teachers write their own individual pedagogic creeds. The pedagogic creed is a “thinking tool” for student teachers, promoting their personal and professional development into their future roles. In writing the creed, they gain the capacity for critical thinking and the language to interpret and justify their thinking professionally. We further recommend including the pedagogic creed as a tool for student teachers throughout the bachelor’s degree program. Furthermore, we identified this as a valuable method for teacher development. While the importance of reflective practice for teachers has long been emphasized, there are few available tools to facilitate reflection. Pedagogic creeds could serve as one such tool. The professional development of educators can be intentionally fostered through both individual and collective engagement, grounded in a deep sense of responsibility and presence (

Latta & Buck, 2007). Additionally, by enabling teachers to share parts of their individual pedagogic creeds, they can provide a platform that is intentionally developed for collective professional development among teachers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Å.N.A., M.O. and A.H.; Methodology, Å.N.A., M.O. and A.H.; Formal analysis, Å.N.A., M.O. and A.H.; Investigation, Å.N.A. and A.H.; Data curation, Å.N.A., M.O. and A.H.; Writing—original draft, A.H., Å.N.A. and M.O.; Writing—review & editing, A.H., Å.N.A., and M.O.; Visualization, A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by Western Norway University of Applied Sciences.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as it utilized fully anonymized interview transcripts that contained no personally identifiable information.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participating students, and only data from those who provided consent were included in the study. All transcripts were anonymized to ensure participant confidentiality.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable because the consents we got to use the data were intended for this article only.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to those who permitted us to use their pedagogic creeds as research data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

Notes

| 1 | The bold words are from the original definition. |

| 2 | This is a translation by the authors. |

| 3 | For confidentiality, we use XX to replace the country name given by the student teacher. |

References

- Austin, Z., & Sutton, J. (2014). Qualitative research: Getting started. CJHP, 67(6), 436–440. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4275140/pdf/cjhp-67-436.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, M., Kaufman, D., & Moss, D. M. (2021). Enhancing orientation to cultural difference: The role of reentry work for teacher candidates studying abroad. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 35(2), 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhuizen, G., & Feryok, A. (2006). Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of a short-term international experience program. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 34(1), 115e134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beelen, J., & Jones, E. (2015). Redefining internationalization at home. In A. Curaj, L. Matei, R. Pricopie, J. Salmi, & P. Scott (Eds.), The European higher education area: Between critical reflections and future policies (pp. 59–72). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2010). Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, politics, democracy (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2013). The beautiful risk of education (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2021). World-centred education. A view for the present. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Black, S. J., & Cutler, B. R. (1997, April 9–12). Sister schools: An experience in culture vision for preservice teachers and elementary children [Paper presentation]. Annual Meeting of the Association for Early Childhood Education International, Portland, OR, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bontekoe, R. (1996). Dimensions of the hermeneutic circle. Humanities Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bransford, J., Darling-Hammond, L., & LePage, P. (2005). Introduction. In L. Darling-Hammond, J. Bransford, P. LePage, K. Hammerness, H. Duffy, & National Academy of Education (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 1–39). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Broeder, P., & Stokmans, M. (2012). The teacher as reflective practitioner: Professional roles and competence domains. International Proceedings of Economics Development and Research, 33, 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, M. C., & Outlaw, M. E. (2002). Student teaching abroad: Learning about teaching, culture, and self. Kappa Delta Pi Record, Summer, 38(4), 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Det Kongelige Kunnskapsdepartment. (2009). Internasjonalisering av utdanning [Internationalization of education] St.meld. nr. 14 (2008–2009). Det Kongelige Kunnskapsdepartment. [Google Scholar]

- de Wit, H., Hunter, F., Howard, L., & Egron-Polak, E. (2015). Internationalization of higher education, study commissioned by policy department B: Structural and cohesion policies. Culture and Education, European Parliament. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/540370/IPOL_STU(2015)540370_EN.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Faulconer, T. (2003, April 21–25). These kids are so bright! Preservice teachers’ insights and discoveries during a three-week student teaching practicum in Mexico [Paper presentation]. Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson, M., & Tait, C. (2012). Teachers as sojourners: Transitory communities in short study-abroad programs. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28, 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmarsdottir, H. B., Baily, S., Skårås, M., Ramos, K., Ege, A., Heggernes, S. L., & Carsillo, T. (2023). Exploring the power of internationalization in teacher education. Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE), 7(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E., Leask, B., Brandenburg, U., & de Wit, H. (2021). Global social responsibility and the internationalisation of higher education for society. Journal of Studies in International Education, 25(4), 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A. (2014). What do professional learning policies say about purposes of teacher education? Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 43(3), 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latta, M. M., & Buck, G. (2007). Professional development risks and opportunities embodied within self-study. Studying Teacher Education, 3(2), 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. F. K. (2011). International field experience—What do student teachers learn? The Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(10), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorhouse, B. L., & Harfitt, G. J. (2021). Pre-service and in-service teachers’ professional learning through the pedagogical exchange of ideas during a teaching abroad experience. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 49(2), 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2017). Framework plan for kindergartens. contents and tasks. Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research. (2009). Internationalization of education in Norway (English summary). Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/a0f91ffae0d74d76bdf3a9567b61ad3f/en-gb/pdfs/stm200820090014000en_pdfs.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Regjeringen. (2006). Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kilde/kd/pla/2006/0002/ddd/pdfv/235560-rammeplan_laerer_eng.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Sahin, M. (2008). Cross-cultural experience in preservice teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(7), 1777–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolcic, E., & Katunich, J. (2017). Teachers crossing borders: A review of the research into cultural immersion field experience for teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 62, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S. Y. F., & Choi, P. L. (2004). The development of personal, intercultural, and professional competence in international field experience in initial teacher education. Asia Pacific Education Review, 5(1), 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO, & International Task Force on Teachers for Education 2030. (2019). Teacher policy development guide. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000370966 (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- Vall, N. G., & Tennison, J. M. (1992). International student teaching: Stimulus for developing reflective teachers. Action in Teacher Education, 13(4), 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M. J., & Ward, C. (2003). Promoting cross-cultural competence in preservice teachers through second language use. Education, 123(3), 532–537. [Google Scholar]

- Willard-Holt, C. (2001). The impact of a short-term international experience for preservice teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(4), 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J., & Grierson, A. (2016). Facilitating Professional Development during International Practicum: Understanding our Work as Teacher Educators through Critical Incidents. Studying Teacher Education, 12(1), 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).