Dimensions of Meaning in Physical Education—Voices from Experienced Teachers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Methodological Approach

2.2. Participants and Selection Criteria

2.3. Instrument and Data Collection Procedure

2.4. Procedure and Data Analysis

3. Results

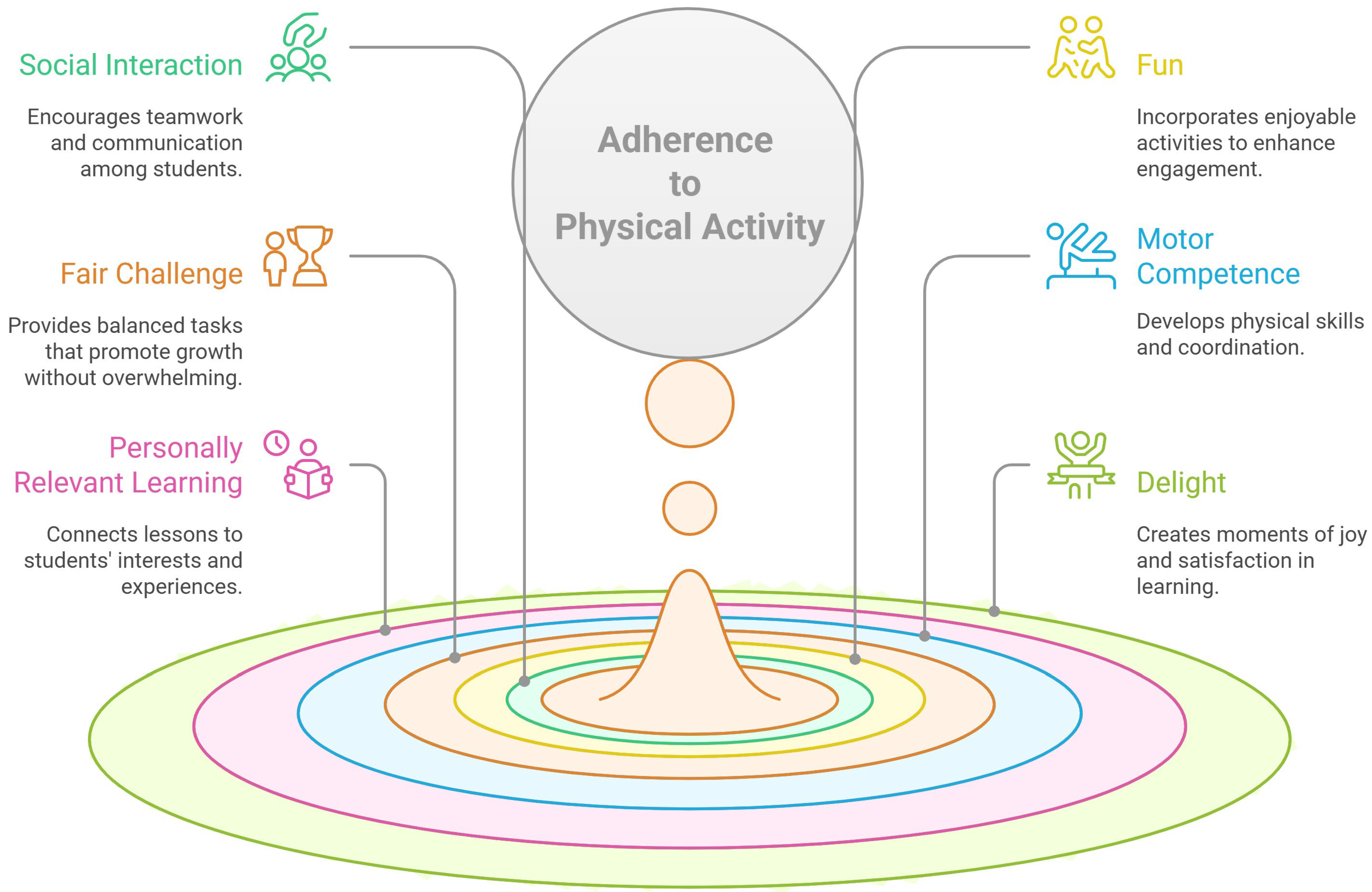

3.1. Social Interaction: Physical Education as a Relational Space

3.2. Fun: The Playful Component as a Driver of Participation

3.3. Fair Challenge: Balancing Demands with Students’ Abilities

3.4. Motor Competence: Feeling Capable as a Driver of Engagement

3.5. Personally Relevant Learning: Connecting PE to Students’ Lives

3.6. Delight: Emotional Experience as a Key to Adherence

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PE | Physical Education |

| MPE | Meaningful Physical Education |

| FA | Absolute Frequency |

| %FA | Percentage of Absolute Frequency |

| UA | University of Alicante |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Ahmadi, A., Noetel, M., Parker, P., Ryan, R. M., Ntoumanis, N., Reeve, J., Beauchamp, M., Dicke, T., Yeung, A., Ahmadi, M., Bartholomew, K., Chiu, T. K. F., Curran, T., Erturan, G., Flunger, B., Frederick, C., Froiland, J. M., González-Cutre, D., Haerens, L., … Lonsdale, C. (2023). A classification system for teachers’ motivational behaviors recommended in self-determination theory interventions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 115(8), 1158–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, C. (1984). Competitive, cooperative and individualistic goal structures: A motivational analysis. In R. Ames, & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation in education. Vol. 1: Student motivation (pp. 177–207). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baena-Extremera, A., Granero-Gallegos, A., Ponce-de-LeónElizondo, A., Sanz-Arazuri, E., Valdemoros-San-Emeterio, M. D. L., & Martínez-Molina, M. (2016). Factores psicológicos relacionados con las clases de educación física como predictores de la intención de la práctica de actividad física en el tiempo libre en estudiantes. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 21(4), 1105–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beni, S., Fletcher, T., & Ní Chróinín, D. (2017). Meaningful experiences in physical education and youth sport: A review of the literature. Quest, 69(3), 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beni, S., Ní Chróinín, D., & Fletcher, T. (2019). A focus on the how of meaningful physical education in primary schools. Sport, Education and Society, 24(6), 624–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S. J., Ciaccioni, S., Thomas, G., & Vergeer, I. (2019). Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: An updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquerra, R. (Ed.). (2004). Metodología de la investigación educativa. La Muralla. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, A., & Kirk, D. (2021). Models-based practice in physical education. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J. E., Hillman, C. H., Castelli, D., Etnier, J. L., Lee, S., Tomporowski, P., Lambourne, K., & Szabo-Reed, A. N. (2016). Physical activity, fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children: A systematic review. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 48(6), 1197–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durden-Myers, E. J., Whitehead, M. E., & Pot, N. (2018). Physical literacy and human flourishing. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 37(3), 308–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Río, J., & Saiz-González, P. (2023). Educación Física con Significado (EFcS). Un planteamiento de futuro para todo el alumnado. Revista Española de Educación Física y Deportes, 437(4), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriz-Valero, A., García-González, L., García-Martínez, S., & Fernández-Río, J. (2024). Motivational factors predicting the selection of elective physical education: Prospective in high school students. Psicología Educativa, 30(2), 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T., & Ní Chróinín, D. (2021). Pedagogical principles that support the prioritisation of meaningful experiences in physical education: Conceptual and practical considerations. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 27(5), 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T., Ní Chróinín, D., Gleddie, D., & Beni, S. (2021). The why, what, and how of meaningful physical education. In T. Fletcher, D. Ní Chróinín, D. Gleddie, & S. Beni (Eds.), Meaningful physical education: An approach for teaching and learning (pp. 3–20). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavira, S. A., & Osuna, J. B. (2015). La triangulación de datos como estrategia en investigación educativa. Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación, (47), 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R., Stevens, G. A., Riley, L. M., & Bull, F. C. (2020). Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health, 4(1), 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-López, J. A., Ochoa-Martínez, P. Y., & Sáenz-López, P. (2019). Participación, motivación y adherencia en Educación Física. e-Motion: Revista de Educación, Motricidad e Investigación, (13), 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hastie, P. A. (2023). Sport pedagogy research and its contribution to the rediscovery of joyful participation in physical education. Kinesiology Review, 12(1), 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howley, D., Dyson, B., & Baek, S. (2024). All the better for it: Exploring one teacher- researcher’s evolving efforts to promote meaningful physical education. European Physical Education Review, 31(1), 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howley, D., Dyson, B., Baek, S., Fowler, J., & Shen, Y. (2022). Opening up neat new things: Exploring understandings and experiences of social and emotional learning and meaningful physical education utilizing democratic and reflective pedagogies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerebine, A., Arundell, L., Watson-Mackie, K., Keegan, R., Jurić, P., Dudley, D., Ridgers, N. D., Salmon, J., & Barnett, L. M. (2024). Effects of holistically conceptualised school-based interventions on children’s physical literacy, physical activity, and other Outcomes: A systematic review. Sports Medicine-Open, 10, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kretchmar, R. S. (2006). Ten more reasons for quality physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 77(9), 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretchmar, R. S. (2007). What to do with meaning? A research conundrum for the 21st century. Quest, 59(4), 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, M., Sisneros, C., & Kazak, Z. (2023). The 3 × 2 achievement goals in the education, sport, and occupation literatures: A systematic review with meta-analysis. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(7), 1130–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubans, D., Richards, J., Hillman, C., Faulkner, G., Beauchamp, M., Nilsson, M., Kelly, P., Smith, J., Raine, L., & Biddle, S. (2016). Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: A systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics, 138(3), e20161642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Miguélez, M. (2004). Ciencia y arte en la metodología cualitativa. Trillas. [Google Scholar]

- Ní Chróinín, D., Fletcher, T., & O’Sullivan, M. (2018). Pedagogical principles of learning to teach meaningful physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(2), 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opstoel, K., Chapelle, L., Prins, F. J., De Meester, A., Haerens, L., van Tartwijk, J., & De Martelaer, K. (2020). Personal and social development in physical education and sports: A review study. European Physical Education Review, 26(4), 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, N., Haycraft, E., Johnston, J. P., & Atkin, A. J. (2017). Sedentary behaviour across the primary-secondary school transition: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine, 94, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Pueyo, Á., Hortigüela Alcalá, D., Casado Berrocal, O., Heras Bernardino, C., & Herrán Álvarez, I. (2022). Análisis y reflexión sobre el nuevo currículo de educación física. Revista Española de Educación Física y Deportes, 463(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivero Alvea, G., & Ries, F. (2023). La Educación Física de Calidad y sus consideraciones para una aplicación teórico-práctica en el aula: Una revisión narrativa. Revista Española de Educación Física y Deportes, 437(1), 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiz-González, P., Sierra-Díaz, J., Iglesias, D., & Fernández-Río, J. (2025). Chasing meaningfulness in Spanish physical education: Old and new features. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Ayala, C. M., & Gastélum-Cuadras, G. (2020). Teoría de la autodeterminación en el contexto de educación física: Una revisión sistemática. Retos, 38, 838–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampasa-Kanyinga, H., Colman, I., Goldfield, G. S., Janssen, I., Wang, J., Podinic, I., Tremblay, M. S., Saunders, T. J., Sampson, M., & Chaput, J. P. (2020). Combinations of physical activity, sedentary time, and sleep duration and their associations with depressive symptoms and other mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17(1), 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. S., Saliasi, E., van den Berg, V., Uijtdewilligen, L., de Groot, R. H. M., Jolles, J., Andersen, L. B., Bailey, R., Chang, Y.-K., Diamond, A., Ericsson, I., Etnier, J. L., Fedewa, A. L., Hillman, C. H., McMorris, T., Pesce, C., Pühse, U., Tomporowski, P. D., & Chinapaw, M. J. M. (2019). Effects of physical activity interventions on cognitive and academic performance in children and adolescents: A novel combination of a systematic review and recommendations from an expert panel. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(10), 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, L. D. (2014). Age of opportunity: Lessons from the new science of adolescence. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Syaukani, A. A., Mohd Hashim, A. H., & Subekti, N. (2023). Conceptual framework of applied holistic education in physical education and sports: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Physical Education Theory and Methodology, 23(5), 794–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telford, R. M., Olive, L. S., Keegan, R. J., Keegan, S., Barnett, L. M., & Telford, R. D. (2020). Student outcomes of the physical education and physical literacy (PEPL) approach: A pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial of a multicomponent intervention to improve physical literacy in primary schools. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 26(1), 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, M. W., Rege, M., & Solheim, O. J. (2022). Teacher relationship skills and student learning. Economics of Education Review, 89, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truelove, S., Bruijns, B. A., Johnson, A. M., Gilliland, J., & Tucker, P. (2020). A meta-analysis of children’s activity during physical education lessons. Health Behavior and Policy Review, 7(4), 292–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utesch, T., Bardid, F., Büsch, D., & Strauss, B. (2019). The relationship between motor competence and physical fitness from early childhood to early adulthood: A meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 49(4), 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcellos, D., Parker, P. D., Hilland, T., Cinelli, R., Owen, K. B., Kapsal, N., Lee, J., Antczak, D., Ntoumanis, N., Ryan, R. M., & Lonsdale, C. (2020). Self-determination theory applied to physical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(7), 1444–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D. E. R., & Bredin, S. S. D. (2017). Health benefits of physical activity: A systematic review of current systematic reviews. Current Opinion in Cardiology, 32(5), 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. L., Bennie, A., Vasconcellos, D., Cinelli, R., Hilland, T., Owen, K. B., & Lonsdale, C. (2021). Self-determination theory in physical education: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 99, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Educational Stage | n | Age ( ± SD) | M Experience | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | 6 | 43.2 ± 3.4 | 17.5 ± 3.1 | 3 | 3 |

| Secondary | 8 | 45.6 ± 4.1 | 19.2 ± 2.8 | 5 | 3 |

| Total | 14 | 44.5 ± 3.9 | 18.5 ± 3.0 | 8 | 6 |

| Dimension | Guiding Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Social Interaction | How do you encourage relationships among students during your classes? What types of dynamics do you use to foster a sense of belonging and collaboration? Do you think your students feel part of the group during PE classes? Why? |

| 2. Fun | How do you value the importance of fun in your PE classes? What signs do you observe in students to know if they are having fun? What strategies do you use to make lessons engaging and motivating? |

| 3. Fair Challenge | What criteria do you use to adapt task difficulty to students’ abilities? Can you give an example of an activity where you set an appropriate challenge for different levels? How do students respond to challenges? Do they feel capable of overcoming them? |

| 4. Motor Competence | How important is the development of physical skills in your planning? What evidence do you observe that students are improving their motor competence? Do you think they feel more confident and effective in their movements over time? |

| 5. Personally Relevant Learning | How do you try to connect physical activities with students’ interests or life experiences? Do you allow them to suggest or adapt activities? What outcomes have you observed when you do? Have you noticed greater engagement when tasks are more connected to their reality? |

| 6. Delight | Do you think students leave your classes with a positive feeling? What tells you so? What elements do you believe are key to making the experience memorable and long-lasting? How does enjoyment influence their attitude toward physical activity outside of school hours? |

| Dimension (Theme) | Interpretative Subtheme | Code (Micro Level) | FA | %FA | Illustrative Quote |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Interaction | Educational value of interaction | ‘PE as a relational space’ | 10 | 71% | ‘It’s in PE where they get to know each other best.’ (TEACH_6) |

| Cooperative strategies | ‘Use of mixed and rotating groupings’ | 9 | 64% | ‘I try to make them work with someone different each day.’ (TEACH_3) | |

| Conflict management | ‘PE as a coexistence lab’ | 5 | 36% | ‘Many conflicts that arise in class are used to educate.’ (TEACH_13) | |

| Fun | Relevance of playfulness | ‘Play as a methodological axis’ | 13 | 93% | ‘If they don’t have fun, they lose interest quickly.’ (TEACH_1) |

| Emotional conditions for enjoyment | ‘Relaxed and safe atmosphere’ | 10 | 71% | ‘I really care that there’s no fear of failure.’ (TEACH_11) | |

| Fair Challenge | Perception of students’ level | ‘Inequality in motor skills’ | 8 | 57% | ‘It’s hard to adapt tasks when there’s so much difference in levels.’ (TEACH_5) |

| Progressive task adjustment | ‘Grading difficulty within the same activity’ | 6 | 43% | ‘Sometimes I create three versions of the same exercise.’ (TEACH_9) | |

| Motor Competence | Valuing technical progress | ‘Importance of visible improvement’ | 11 | 79% | ‘They feel motivated when they see they’re mastering the movements.’ (TEACH_2) |

| Positive feedback | ‘Reinforcing effort, not just outcome’ | 7 | 50% | ‘I praise them when I see they’re trying, even if they don’t succeed.’ (TEACH_10) | |

| Personally Relevant Learning | Connection to students’ context | ‘Activities linked to daily life’ | 5 | 36% | ‘We adapt some games to what they do at home or in the street.’ (TEACH_12) |

| Student participation | ‘Partial choice of content or dynamics’ | 4 | 29% | ‘Sometimes I let them choose between two options, and that motivates them.’ (TEACH_4) | |

| Delight | Lasting emotional impact | ‘Experiences that stay in memory’ | 6 | 43% | ‘Years later, they tell you they remember a specific class.’ (TEACH_8) |

| Personal satisfaction | ‘Classes that make them feel good’ | 10 | 71% | ‘You can tell when they leave happy, even if they’re sweating.’ (TEACH_7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Girona-Durá, C.; López-Bautista, I.; García-Taibo, O.; Baena-Morales, S. Dimensions of Meaning in Physical Education—Voices from Experienced Teachers. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1166. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091166

Girona-Durá C, López-Bautista I, García-Taibo O, Baena-Morales S. Dimensions of Meaning in Physical Education—Voices from Experienced Teachers. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1166. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091166

Chicago/Turabian StyleGirona-Durá, Carla, Iván López-Bautista, Olalla García-Taibo, and Salvador Baena-Morales. 2025. "Dimensions of Meaning in Physical Education—Voices from Experienced Teachers" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1166. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091166

APA StyleGirona-Durá, C., López-Bautista, I., García-Taibo, O., & Baena-Morales, S. (2025). Dimensions of Meaning in Physical Education—Voices from Experienced Teachers. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1166. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091166