Reframing Academic Development for the Ecological University: From ‘Change’ to ‘Growth’

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Knowledges

3. Becoming Teachers

- Small inputs can lead to dramatically large consequences.

- Global properties flow from the aggregate behaviour of individuals.

- Slight differences in initial conditions can produce very different outcomes.

- Complex adaptive systems can produce very different outcomes.

4. Curation of the Third Space

who are primarily responsible for developing, maintaining and changing the social, digital and physical infrastructure that enables education, research and knowledge exchange.

5. The Structure of Academic Development

- Ecological resilience is concerned with learning from and developing with disturbances that are recognized as a normal component of a fluctuating environment (Folke et al., 2021). This is achieved by focusing on characteristics of persistence, adaptability, variability and unpredictability (Holling, 1996). These are characteristics that can ensure continuing viability in an environment where important factors lie outside the control of individuals within the system. It might be given the short-hand label of ‘futureproofing’ or ‘sustainability’.

- Epistemic humility requires that one examines assumptions of cognitive authority to ensure that we do not suppress diverse or minority viewpoints (Potter, 2022). This can create a valuable rhythm of alternating knowledge and ignorance (Parviainen et al., 2021) that allows the academic developer to simultaneously acknowledge the subject expertise and cultural knowledge brought by course participants within their novicehood of teaching.

- Epistemological rehabilitation refers to an appreciation of the many facets of epistemology and the way in which some facets can be used to maintain a limited perspective while others open the door to fresh ideas and new possibilities. The constructs of epistemological injustice (Fricker, 2007) and epistemological narrowing (Mormina, 2022) help to maintain islands of knowledge while epistemological vulnerability (Gilson, 2014) and epistemological flexibility (Osborne et al., 2021) offer a wider and more fluid perspective. Recognition of this complex epistemological cartography can facilitate an epistemological rehabilitation (Kinchin, 2025), representing a trajectory for the epistemic development of the field.

6. Resource Impoverishment

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, E. (2021). Being before: Three Deleuzian becomings in teacher education. Professional Development in Education, 47(2–3), 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, M. (2002). Travelling concepts in the humanities: A rough guide. University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Begon, M., Harper, J. L., & Townsend, C. R. (1986). Ecology: Individuals, populations and communities. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, B. (1999). Vertical and horizontal discourse: An essay. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 20(2), 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlmann, J. (2022). Decolonising learning development through reflective and relational practice. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boshier, R. (2009). Why is the scholarship of teaching and learning such a hard sell? Higher Education Research & Development, 28(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, C., & Mallinson, D. (2024). Measuring the stasis: Punctuated equilibrium theory and partisan polarization. Policy Studies Journal, 52(1), 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coté, M., Day, R., & de Peuter, G. (2007). Utopian pedagogy: Creating radical alternatives in the neoliberal age. The Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 29(4), 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davids, N., & Waghid, Y. (2019). Teaching and learning as a pedagogic pilgrimage: Cultivating faith, hope and imagination. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong, S. (2024). A novel definition of professional staff. In S. Kerridge, S. Poli, & Yang-Yoshihara (Eds.), The emerald handbook of research management and administration around the world (pp. 99–112). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Drumm, L. (2025). Becoming rhizome: Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizome as theory and method. In J. Huisman, & M. Tight (Eds.), Theory and method in higher education research (Vol. 10, pp. 37–55). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, L. (1991). A biosocial theory of social stratification derived from the concepts of pro/antisociality and r/K selection. Politics and the Life Sciences, 10(1), 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L. (2002). Reflective practice in educational research: Developing advanced skills. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, L. (2024). What is academic development? Contributing a frontier-extending conceptual analysis to the field’s epistemic development. Oxford Review of Education, 50(4), 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanghanel, J., & Trowler, P. (2008). Exploring academic identities and practices in a competitive enhancement context: A UK-based case study. European Journal of Education, 43(3), 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C., Carpenter, S., Elmqvist, T., Gunderson, L., & Walker, B. (2021). Resilience: Now more than ever. Ambio, 50, 1774–1777. Available online: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol10/iss2/art22/ (accessed on 3 August 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossland, T., & Sandvoll, R. (2023). Drivers for educational change? Educational leaders’ perceptions of academic developers as change agents. International Journal for Academic Development, 28(3), 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilson, E. (2014). The ethics of vulnerability: A feminist analysis of social life and practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, S. J. (1991). Exaptation: A crucial tool for an evolutionary psychology. Journal of Social Issues, 47(3), 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J. H., Callanan, G. A., & Powell, G. N. (2024). Advancing research on career sustainability. Journal of Career Development, 51(4), 478–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R. (2004). Knowledge production and the research–teaching nexus: The case of the built environment disciplines. Studies in Higher Education, 29(6), 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, M., Parrish, J., Heppell, S., Augustine, S., Campbell, L., Divine, L., Donatuto, J., Groesbeck, A., & Smith, N. (2023). Boundary spanners: A critical role for enduring collaborations between indigenous communities and mainstream scientists. Ecology and Society, 28(1), art. 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C. S. (1996). Engineering resilience vs. ecological resilience. In P. C. Schultze (Ed.), Engineering within ecological constraints (pp. 31–43). National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, C. S. (2001). Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological, and social systems. Ecosystems, 4, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illes, L. M. (1999). Ecosystems and villages: Using transformational metaphors to build community in higher education institutions. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 21(1), 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jax, K. (2007). Can we define ecosystems? On the confusion between definition and description of ecological concepts. Acta Biotheoretica, 55(4), 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandlbinder, P., & Peseta, T. (2009). Key concepts in postgraduate certificates in higher education teaching and learning in Australasia and the United Kingdom. International Journal for Academic Development, 14(1), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

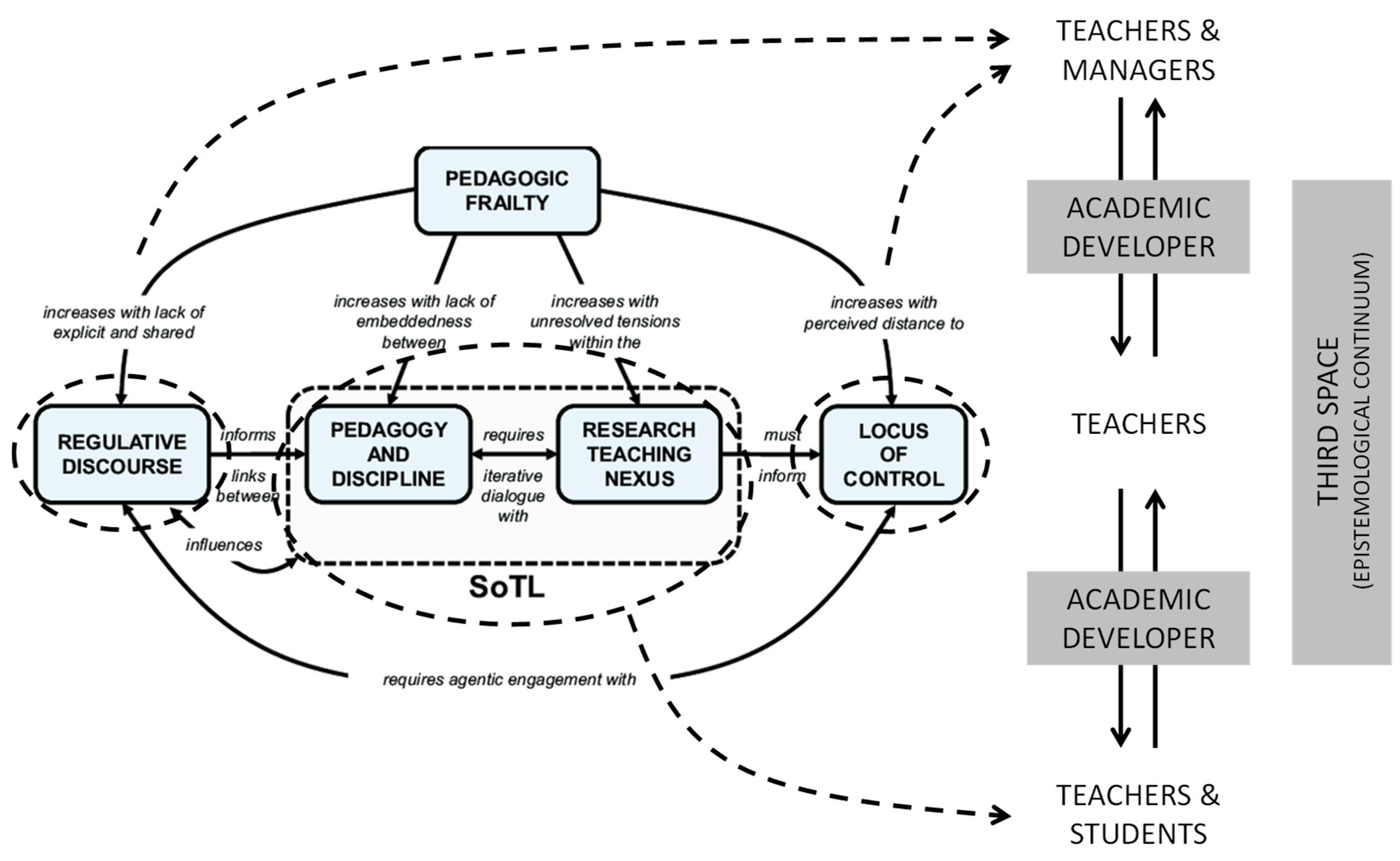

- Kinchin, I. M. (2017). Visualising the pedagogic frailty model as a frame for the scholarship of teaching and learning. PSU Research Review, 1(3), 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I. M. (2022a). An ecological lens on the professional development of university teachers. Teaching in Higher Education, 27(6), 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I. M. (2022b). Exploring dynamic processes within the ecological university: A focus on the adaptive cycle. Oxford Review of Education, 48(5), 675–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I. M. (2024). How to mend a university: Towards a sustainable learning environment in higher education. Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Kinchin, I. M. (2025). Teaching as an ecological consilience. In I. M. Kinchin (Ed.), Reclaiming the teaching discourse in higher education: Curating a diversity of theory and practice (pp. 199–216). Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Kinchin, I. M., & Correia, P. R. M. (2025). Reimaging management for the ecological university. In C. Machado, & J. P. Davim (Eds.), Management in higher education for sustainability (pp. 113–126). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kinchin, I. M., Heron, M., Hosein, A., Lygo-Baker, S., Medland, E., Morley, D., & Winstone, N. E. (2018). Researcher-led academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 23(4), 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I. M., & Pugh, S. (2024). Ecological dynamics in the third space: A diffractive analysis of academic development. London Review of Education, 22(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinchin, I. M., & Winstone, N. E. (Eds.). (2017). Pedagogic frailty and resilience in the university. Sense. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, S., & Suri, H. (2024). Demystifying academic development practice. Higher Education Research & Development, 44, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, R. (1999). Complexity: Life at the edge of chaos. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Linder, K. E., & Felten, P. (2015). Understanding the work of academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 20(1), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, D., Green, D. A., & Hoption, C. (2018). A lasting impression: The influence of prior disciplines on educational developers’ research. International Journal for Academic Development, 23(4), 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lygo-Baker, S. (2019). Valuing uncertainty. In S. Lygo-Baker, I. M. Kinchin, & N. E. Winstone (Eds.), Engaging students voices in higher education: Diverse perspectives and expectations in partnership (pp. 245–260). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lygo-Baker, S. (2025). Teaching is not just done by ‘teachers’. In I. M. Kinchin (Ed.), Reclaiming the teaching discourse in higher education: Curating a diversity of theory and practice (pp. 71–87). Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane, B. (2021). The neoliberal academic: Illustrating shifting academic norms in an age of hyper-performativity. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 53(5), 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, C. (2020). Academic developers as brokers of change: Insights from a research project on change practice and agency. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(2), 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaught, C. (2020). A narrative across 28 years in academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(1), 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, M. (2024). Knowledge in the university. In M. Meredith (Ed.), Universities and epistemic justice in a plural world: Knowing better (pp. 47–58). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Young, J., & Poth, C. N. (2022). ‘Complexifying’ our approach to evaluating educational development outcomes: Bridging theoretical innovations with frontline practice. International Journal for Educational Development, 27(4), 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morini, L. (2020). The anti-ecological university: Competitive higher education as ecological catastrophe. Philosophy and Theory in Higher Education, 2(2), 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mormina, M. (2022). Knowledge, expertise and science advice during COVID-19: In search of epistemic justice for the “wicked” problems of post-normal times. Social Epistemology, 36(6), 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrish, L., & Sauntson, H. (2020). Academic irregularities: Language and neoliberalism in higher education. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, E., Anderson, V., & Robson, B. (2021). Students as epistemological agents: Claiming life experience as real knowledge in health professional education. Higher Education, 81(4), 741–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parviainen, J., Koski, A., & Torkkola, S. (2021). “Building a ship while sailing it.” Epistemic humility and the temporality of non-knowledge in political decision making on COVID-19. Social Epistemology, 35(3), 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Guzmán, D. M. (2018). Canguilhem’s concepts. Transversal: International Journal for the Historiography of Science, 4, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Potter, N. N. (2022). The virtue of epistemic humility. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 29(2), 121–123. Available online: https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/858754/summary?casa_token=-OLjBIBdXnAAAAAA:FhUv8pwRRWUnRicpjrKFJ8CIEPPjgS-ej7FEvbV7uygaUG6Yei8-i4i2Lauo1xfNYlRUV2R1 (accessed on 3 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Rowland, S. L., & Myatt, P. M. (2014). Getting started in the scholarship of teaching and learning: A “how to” guide for science academics. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 42(1), 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B. D. S. (2016). Epistemologies of the south: Justice against epistemicide. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Skopec, M., Fyfe, M., Issa, H., Ippolito, K., Anderson, M., & Harris, M. (2021). Decolonization in a higher education STEMM institution—Is ‘epistemic fragility’ a barrier? London Review of Education, 19(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, R. (2003). Concepts of change: Enhancing the practice of academic staff development in higher education. International Journal for Academic Development, 8(1–2), 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfeld, J., Graham, M. A., & Ebersöhn, L. (2023). Time to flock: Time together strengthens relationships and enhances trust to teach despite challenges. Teachers and Teaching, 29(1), 70–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D. (2018). Bolt-holes and breathing spaces in the system: On forms of academic resistance (or, can the university be a site of utopian possibility?). The Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 40(2), 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitchurch, C. (2008). Shifting identities and blurring boundaries: The emergence of third space professionals in UK higher education. Higher Education Quarterly, 62(4), 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kinchin, I.M. Reframing Academic Development for the Ecological University: From ‘Change’ to ‘Growth’. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091159

Kinchin IM. Reframing Academic Development for the Ecological University: From ‘Change’ to ‘Growth’. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091159

Chicago/Turabian StyleKinchin, Ian M. 2025. "Reframing Academic Development for the Ecological University: From ‘Change’ to ‘Growth’" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091159

APA StyleKinchin, I. M. (2025). Reframing Academic Development for the Ecological University: From ‘Change’ to ‘Growth’. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1159. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091159