1. Introduction

In an increasingly globalized academic and professional landscape, English language proficiency is no longer a mere asset but a necessity—especially in multilingual, postcolonial nations such as Pakistan. English is used in higher education either as a medium of instruction, a gateway to international scholarship, or a socio-economic marker of upward mobility (

Rahman, 2002;

Mansoor, 2003). Nevertheless, Pakistani learners are typically placed in an emotionally fraught context when studying English due to the large classes, teacher-centred pedagogical models, exam-focused evaluation, and linguistic hierarchies that marginalize native languages (

Ahmed et al., 2023;

Anwar et al., 2021). In this kind of system, the mental and emotional welfare of EFL learners becomes paramount, not just as an adjunct consideration but the core determinant of language learning success. Although the role of emotional variables in second language acquisition is acknowledged, language-related anxieties, low engagement, fluctuating motivation, and negative attitudes are yet to be well studied in the EFL/ESL context in Pakistan.

Although research in the field of second language acquisition (SLA) has long been dominated by the role of cognitive variables and the work of teaching methods, the increasing amount of evidence suggests the dominant role of emotional constructs in determining the course of language acquisition (

Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2016;

Shao et al., 2020). Among these, Trait Emotional Intelligence (TEI) has been identified as a strong predictor of learners’ affective and behavioural outcomes.

Petrides and Furnham (

2001) describe TEI as a constellation of emotion-related self-perceptions and behavioural dispositions, including such domains as emotionality, self-control, sociability, and well-being. In contrast to ability-based versions of measuring emotional intelligence, which assess an individual’s performance under ideal circumstances, TEI reflects an individual’s perceptions of and self-control over emotional processes in real-life situations (

Petrides et al., 2007). Across a wide range of educational contexts, a large body of research has correlated high TEI with greater learner resilience (

Kirk et al., 2023), an expanded sense of engagement (

Alamer & Alrabai, 2024), increased motivation (

Imamyartha et al., 2023), greater enjoyment of language (

Dewaele & Li, 2021), and a decreased level of foreign language anxiety (

Jin et al., 2024;

Mede & Budak, 2021).

These findings are not only theoretically persuasive but also practically significant. Learners with high TEI are confident, persistent, and flexible in their language learning methods and usually convert their emotional resources into academic achievements (

Abdolrezapour, 2018;

Li et al., 2021). Emotionality leads to empathy and self-discovery, allowing the students to understand interpersonal relationships in language classrooms (

J. Zhang & Zhang, 2023). The ability to control emotions is supported by self-control when performing specific high-stakes actions (i.e., oral presentation or an exam) (

Chen & Zhang, 2022). Sociability leads to classroom interactions, cooperating with fellow students, and communication readiness (

Isohätälä et al., 2019). In the meantime, well-being fosters emotional stability, enabling a consistent drive and positive self-evaluation (

Thao et al., 2023). Given this extensive evidence base, TEI has increasingly been integrated into educational psychology models and teacher development frameworks (

Hen & Sharabi-Nov, 2014;

Kirk et al., 2023).

However, this global consensus on TEI’s efficacy masks a fundamental issue: most existing research is geographically concentrated in Western and East Asian contexts, with limited exploration of regions in the Global South, such as Pakistan (

Qanwal & Ghani, 2023). Studies from Saudi Arabia (

Aljasir, 2024;

Almusharraf & Bailey, 2021), China (

Chen et al., 2021;

Li et al., 2021), and Indonesia (

Imamyartha et al., 2023) highlight how sociocultural variables mediate the effects of TEI, but their insights are not easily generalizable to Pakistan, where linguistic hybridity, institutional hierarchies, and resource disparities create a distinct emotional ecology for language learners. While

Ahmed et al. (

2023) found a positive link between emotional intelligence and motivation in Pakistani students, and

Anwar et al. (

2021) examined teachers’ TEI concerning classroom performance, comprehensive studies examining TEI’s role across multiple affective variables—specifically attitudes, motivation, engagement, and anxiety—are conspicuously absent. The mechanisms through which TEI operates within Pakistan’s rigid, exam-intensive system remain unexplored.

This lack of localized evidence constitutes not only a theoretical gap but a practical barrier to effective pedagogical reform. Without understanding how emotional self-perceptions interact with Pakistan’s classroom dynamics—where public speaking may provoke severe anxiety, or peer collaboration may be structurally limited—educators are left without contextually relevant strategies for fostering emotional competence. Additionally, TEI facets may not function equally in all cultures because what applies in one country may not be applicable in another (

Petrides et al., 2016). For example, emotionality, which is considered beneficial in Western classrooms, may not be suitable in Pakistan, where showing emotion is culturally discouraged (

Rahman, 2002). Correspondingly, sociability can be counterbalanced in teacher-centred classrooms where peer contact is discouraged. A particularly novel dimension is the emergent auxiliary facet of TEI: the capacity for contextual adaptability, such as navigating Urdu–English code-switching or adjusting behavior across hierarchical learning environments—skills that are especially relevant in linguistically complex and culturally stratified educational contexts.

In response to these conceptual and empirical deficiencies, the present study makes a principal claim: Trait Emotional Intelligence is a context-contingent psychological resource that predicts Pakistani EFL learners’ affective outcomes in distinct, culturally modulated ways. Drawing upon a large-scale empirical dataset, this research explores how core TEI components—emotionality, self-control, sociability, and well-being—and the auxiliary facet predict learners’ attitudes, motivation, engagement, and foreign language anxiety. Unlike previous studies that assume universal functionality of TEI, this research posits that TEI’s predictive strength is filtered through the sociocultural and pedagogical structures of Pakistani Education. Specifically, it investigates how anxiety—not attitude—may serve as the dominant mediator between TEI and motivation, and how contextually unique competencies such as linguistic adaptability may constitute critical but previously unrecognized elements of emotional intelligence in the Global South.

Research Questions

To systematically investigate these theoretical gaps and empirical uncertainties, this study employs a comprehensive framework that examines both the direct effects of TEI components and their contextual moderation within Pakistan’s unique educational landscape. The research design addresses three interconnected dimensions: the predictive relationships between TEI facets and affective outcomes, the mediating mechanisms through which these relationships operate, and the moderating influence of Pakistan’s socio-educational context on these psychological processes.

Q1: How do the core components of Trait Emotional Intelligence (emotionality, self-control, sociability, and well-being) and the emergent auxiliary facet collectively predict Pakistani EFL learners’ attitudes, motivation, engagement, and foreign language anxiety?

Q2: To what extent do attitudes and foreign language anxiety mediate the relationship between TEI and learners’ motivation/engagement in Pakistan’s socio-educational context?

Q3: How does Pakistan’s unique socio-educational environment (e.g., exam pressure and teacher-centred pedagogy) moderate the relationships between TEI components and affective learning outcomes?

By addressing these questions, this study advances the field of applied linguistics and educational psychology in two key ways. First, it recalibrates the global TEI framework to reflect the emotional realities of learners in non-Western, exam-centric systems. Second, it offers evidence-based recommendations for integrating emotional intelligence into Pakistan’s EFL pedagogy—transforming TEI from a static personality trait into a dynamic, teachable skill aligned with local educational needs. In doing so, it not only fills a significant research gap but also contributes toward a more equitable and culturally responsive model of language education.

2. Literature Review

Trait Emotional Intelligence (TEI) is increasingly recognized as a central psychological framework influencing learners’ affective experiences in second and foreign language acquisition. Conceptualized by

Petrides and Furnham (

2001), TEI refers to a constellation of self-perceived emotional competencies situated within personality hierarchies. Unlike ability-based emotional intelligence models that focus on maximum emotional performance, TEI emphasizes how individuals subjectively perceive their capacity to process emotional information in everyday settings (

Petrides et al., 2007;

Andrei et al., 2016;

Li & Xu, 2019).

TEI comprises four well-established core facets—Emotionality, Self-Control, Sociability, and Well-Being. Emotionality involves the ability to perceive, express, and manage emotions, both one’s own and others’, facilitating empathy and interpersonal understanding (

Chen & Zhang, 2022). Self-Control pertains to the regulation of impulsive behaviors and emotional reactions, especially under stress (

Alamer & Alrabai, 2024). Sociability reflects social competence, including communication skills and confidence in managing social interactions (

T. Zhang et al., 2024). Well-being encapsulates emotional stability, optimism, and self-esteem, often serving as a buffer against negative affective states (

Fredrickson, 2001;

Li et al., 2021). These TEI components are theorized to collectively influence learners’ affective states and behaviors in educational contexts. Their predictive power over critical variables such as motivation, Engagement, anxiety, and attitudes is now well established across diverse cultural and linguistic environments (

Dewaele et al., 2018;

Jin et al., 2024).

Attitudes toward language learning—encompassing learners’ beliefs, emotions, and predispositions toward English—are key predictors of persistence, enjoyment, and overall success in EFL contexts (

Gardner, 1985;

Shafiee Rad & Hashemian, 2022). Empirical research indicates a consistent and positive relationship between TEI and language learning attitudes. Learners with high TEI generally display more positive orientations toward language tasks, viewing difficulties as manageable challenges rather than threats (

Li & Xu, 2019;

Jin et al., 2024).

Among TEI components, emotionality and well-being appear to exert the most direct influence on attitudes. Learners with strong emotional awareness and emotional stability are more likely to approach language learning with confidence and optimism (

Chen et al., 2021;

Cao et al., 2022;

Alamer & Alrabai, 2024).

Self-control enhances resilience by enabling students to cope with setbacks without allowing isolated negative experiences to crystallize into persistent negative beliefs (Chen & Zhang, 2022; Shafiee Rad & Hashemian, 2022). Sociability, through its facilitation of positive peer and teacher relationships, enhances the classroom climate, leading to more favorable attitudes toward English and its use (

X. Zhang, 2022;

Chen et al., 2021).

Engagement and motivation are dynamic indicators of sustained learning, with TEI playing a central role in shaping both constructs. Motivation refers to the internal drive to initiate and sustain learning, while Engagement encompasses cognitive, behavioral, and emotional involvement in learning activities (

Fredricks et al., 2004;

Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2021).

Multiple studies have linked high TEI to enhanced intrinsic motivation, sustained effort, and goal persistence. This is primarily facilitated by the learner’s capacity to manage emotional disruptions (self-control), maintain a positive sense of self (well-being), and derive satisfaction from social and communicative aspects of language learning (

Aljasir, 2024;

Imamyartha et al., 2023;

McEown et al., 2023). In collectivist or high-context cultures, TEI also enhances Willingness to Communicate (WTC)—a key motivational correlate—by strengthening learners’ confidence in social and linguistic interactions (

J. Zhang & Zhang, 2023;

Alamer & Alrabai, 2024).

Engagement, too, is shaped by TEI.

Cognitive Engagement is strengthened through the regulation of frustration and focus maintenance (

Ge, 2025;

Yang & Rui, 2025), while

behavioral Engagement is enhanced by perseverance and classroom participation (

Jin et al., 2024;

Z. Wang et al., 2022).

Emotional Engagement, encompassing enjoyment, curiosity, and a sense of belonging, is strongly predicted by well-being and emotionality (

Li et al., 2021;

M. Wang & Wang, 2024;

X. Wang & Wang, 2024). Domain-specific scales like

Alamer and Alrabai’s (

2024) L2-TEI instrument further validate these relationships across cultural contexts.

Yet, in Pakistan’s exam-intensive environment, motivation may be heavily extrinsic (career-focused), and engagement may be limited by systemic factors such as lecture-heavy instruction. Whether TEI’s motivational and engagement-enhancing mechanisms translate into such settings remains largely speculative, indicating a significant research gap.

Foreign Language Anxiety (FLA) is one of the most debilitating affective barriers to language learning, particularly in oral and performance-based tasks (

Horwitz et al., 1986). TEI has consistently been shown to exert a negative predictive effect on FLA across global studies (

Chen & Zhang, 2022;

Mede & Budak, 2021;

Ye et al., 2024). This inverse relationship is mediated by several emotional competencies.

Self-control serves as the core anxiety-regulation mechanism, enabling learners to recognize early signs of stress and implement adaptive coping strategies (e.g., reappraisal, mindfulness) before anxiety impairs cognitive performance (

Chen et al., 2021;

Halil, 2024).

Emotionality contributes by fostering greater emotional literacy, allowing students to differentiate between temporary discomfort and chronic anxiety, which reduces overreactions in high-stakes situations (

Polychroni et al., 2024).

Well-being helps students reframe anxiety-inducing situations (e.g., public speaking) as manageable rather than threatening, supporting emotional resilience (

Shao et al., 2020).

Sociability offers a relational buffer: emotionally intelligent students are more likely to seek reassurance from peers or instructors, reducing isolation and perceived threat (

Chen et al., 2021). Additionally, TEI indirectly lowers FLA by promoting

Foreign Language Enjoyment (FLE), which counters anxiety by increasing learners’ sense of safety and belonging (

Dewaele & Li, 2021;

Li et al., 2021).

While TEI has been widely linked to positive affective outcomes in language learning, most findings originate from collaborative, student-centred contexts. In contrast, Pakistan’s exam-driven, teacher-centred EFL classrooms—with limited peer interaction and emotional support—may suppress key TEI dimensions like sociability and self-control. Motivation tends to be extrinsically driven, and Engagement is often constrained by rigid instructional practices. Moreover, the cultural stigma around emotional expression and punitive assessments may heighten foreign language anxiety (FLA), potentially diminishing TEI’s typical buffering effects. These factors raise critical questions about whether TEI functions similarly in such environments, highlighting the need for context-specific research to understand how TEI operates within Pakistan’s unique socio-educational landscape.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study employed a quantitative, non-experimental correlational design to examine the predictive relationships between Trait Emotional Intelligence (TEI) and key affective variables (attitudes, motivation, Engagement, anxiety) among Pakistani EFL/ESL learners. The cross-sectional design facilitated simultaneous measurement of all variables through standardized instruments, allowing examination of both direct effects and interrelationships among constructs. The non-probability purposive sampling technique targeted higher education institutions in Pakistan to ensure contextual relevance.

3.2. Participants and Context

The study involved 515 EFL/ESL learners (56.5% female, 43.5% male) from Pakistani higher education institutions (97.7% public, 2.3% private). Participants were predominantly aged 18–25 (99.6%), reflecting the target undergraduate population as given in

Table 1. The regression analyses employed five primary predictors representing TEI facets (emotionality, self-control, sociability, well-being, and auxiliary facet). With 515 participants, this yields a cases-to-predictor ratio of 103:1, far exceeding both the conservative 10:1 minimum and the preferred 15:1 ratio recommended for stable parameter estimation (

Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019), ensuring adequate statistical power and reliable coefficient estimates.

3.3. Instrumentation

The study employed a multi-scale instrument package comprising five validated psychometric tools, each adapted to ensure cultural and contextual relevance for Pakistani EFL learners. Primary constructs were measured using established instruments with documented psychometric properties, modified through rigorous translation and validation procedures. Five validated instruments measured the core constructs using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). The reliability test was carried out in SPSS to ensure the tool was well-constructed, as shown in

Table 2.

The Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire-Short Form (TEIQue-SF), originally developed by

Petrides (

2009) and

Cooper and Petrides (

2010), served as the foundational measure for the independent variable. This 30-item adaptation retained the core theoretical framework assessing four facets—Emotionality (emotion perception and expression, e.g., “I’m aware of the non-verbal messages other people send”), Self-Control (impulse regulation, e.g., “I’m usually able to influence the way other people feel”), Sociability (relationship management, e.g., “I can deal effectively with people”), and Well-being (emotional stability, e.g., “I generally believe that things will work out fine in my life”)—while optimizing item clarity for the Pakistani educational context through semantic adjustments (e.g., replacing culturally ambiguous metaphors with direct statements). Dependent variables were measured using contextually modified scales. Attitudes toward English Language Learning utilized a 20-item scale adapted from

Gardner’s (

1985) Attitude/Motivation Test Battery (AMTB), reframing items to reflect contemporary Pakistani learning contexts (e.g., “Learning English is important for my future career in Pakistan”). Language Learning Motivation was assessed through a 6-item short form derived from

Noels et al.’s (

2000) Self-Regulation Questionnaire, prioritizing intrinsic/extrinsic dimensions most salient in collectivist settings (e.g., “I learn English because it connects me to global opportunities”). Learning Engagement employed an 8-item version of

Fredricks et al.’s (

2004) multidimensional scale, distilling items to capture cognitive (“I try hard to understand complex English texts”), behavioral (“I volunteer answers in English class”), and emotional engagement (“I feel excited during English lessons”) with contextual examples from Pakistani classrooms. Foreign Language Anxiety was assessed based on an 8-item adaptation of the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS), which was developed by

Horwitz et al. (

1986), where communication apprehension items that relate to oral proficiency issues in Pakistan were retrieved (e.g., “I worry about making mistakes when speaking English with classmates”).

A three-phase protocol of rigorous adaptation was applied to all measurement tools in order to make them linguistically, culturally, and psychometrically appropriate to the population of the Pakistani EFL learners. This began with formal forward-backward translation involving a group of trained and certified bilingual linguists in which the items were initially translated out of English into Urdu and back to English separately to detect and accordingly correct semantic differences so as to maintain the elements of conceptual equivalence with a view to maximizing local understanding. The validated tools were then put to empirical test by virtue of pilot testing a representative subsample of 80 Pakistani undergraduates, reflecting the target population. This step underlined excellent scale reliability with Cronbach alpha coefficients ranging between the acceptable range of 0.724 (Foreign Language Anxiety scale) and high degrees of consistency of up to 0.857 (Attitude scale). Lastly, psychometric improvement was also administered with the help of exploratory factor analysis, resulting in the removal of four troublesome items that showed inadequate factor loadings below the 0.40 cut-off, thus improving construct validity and measurement accuracy of a final instrument battery, without compromising theory.

3.4. Data Collection Procedure

Data collections were made according to a normative and ethical protocol to guarantee the methodological rigor and well-being of the participants. After having secured official authorization of the involved higher education institutions, prospective participants received detailed disclosure regarding the purpose and methodology of the study, as well as their rights as subjects. Google Form-based questionnaires were forwarded to the participants through their teachers during scheduled classes so that there was standardization in the data collection sites. All questionnaire items were designated as mandatory to ensure complete datasets for statistical analysis. A validated instrument package of Trait Emotional Intelligence (TEI) was administered along with questions assessing their attitudes, motivation, engagement, and anxiety that took roughly between 20 and 25 min to complete. Of the 547 initially recruited participants, 515 provided complete responses, yielding a completion rate of 94.1%. The 32 incomplete responses (5.9% attrition) were excluded from analysis following listwise deletion protocols.

Given the mandatory response format, systematic missing data within completed questionnaires was minimal (<0.5%). For the few instances of inadvertent missing responses, mean imputation was employed for individual scale items when fewer than 10% of items within a given construct were missing, following established guidelines for psychometric data (

Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). Cases with missing data exceeding this threshold were excluded from analysis. No patterns of systematic missingness were detected across demographic groups or questionnaire sections. To ensure response validity, attention check items were embedded within scales, and completion times were monitored to identify potential careless responding. Responses completed in under 10 min or exhibiting straight-line responding patterns were flagged for additional review. The responses were collected with the use of coded identification instead of personal identifiers to maintain the anonymity of the participants during electronic data entry.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

Internationally accepted ethical standards of research in human subjects were strictly followed in the study. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) was consulted to obtain the university’s approval before the study was conducted (Ref: BZU/IRB/2025-06 dated 3 March 2025). The informed consent process also clearly spelled the essence of the research, procedures and hypothetical risks (which are minimal), and the benefits, as well as the measures put in place to guarantee confidentiality. The participants were also guaranteed no adverse academic or institutional consequences for not participating in any research phase. Each participant signed a written informed consent before the administration of the questionnaire, being made aware that their participation was voluntary and that they were able to withdraw at any point without any penalty. Any gathered information was treated through the rigorous anonymization approach in both the collection and analysis stages. Across the entire research process, including data collection and publication, the privacy of the information obtained about the participants was maintained by de-identifying and aggregating the findings. Such extensive safeguards were prepared to ensure the preservation of the welfare of participants without compromising the scientific integrity, especially focusing on the psychological comfort of respondents when dealing with sensitive aspects of the affective dimension of language learning.

3.6. Data Analysis Procedure

This analytical strategy used a two-step sequential methodology to give a full coverage of the research questions. The first preliminary tests were performed in SPSS version 27.0 to have a baseline understanding of the dataset. This was achieved by producing descriptive statistics and frequency distributions to characterize the demographics of the participants and plot overall tendencies across the key variables, the results of which were recorded as supporting materials. Subsequent inferential analysis leveraged SmartPLS 4.1.1.0 software to examine predictive relationships through advanced multivariate techniques. Given the observed non-normal distribution of data, a non-parametric bootstrapping approach with 5000 resamples was implemented as the primary analytical framework. Using the bootstrapping method, which is a non-parametric procedure, allows us “to statistical inference based on building a sampling distribution for a statistic by resampling from the data at hand” (

Fox, 2002, p. 1).

Ringle et al. (

2024) reinforced that “Bootstrapping is a non-parametric procedure for testing whether linear regression model estimates are significant by determining their standard errors using resampling.” (

Ringle et al., 2024). This robust methodology enabled examination of both facet-level and global effects: multiple regression analyses first assessed how individual Trait Emotional Intelligence components (Emotionality, Self-Control, Sociability, Well-being) independently predicted each affective outcome (attitudes, motivation, Engagement, anxiety), followed by parallel analyses examining TEI as a holistic construct.

Path analysis further tested hypothesized mediation effects, evaluating whether TEI’s influence on motivation and Engagement operated indirectly through attitudes and anxiety reduction. To determine the relative importance of specific TEI components in predicting each outcome variable, relative weight analysis was performed. Finally, moderated regression models investigated contextual influences by testing whether socio-educational factors altered TEI-affect relationships. Throughout inferential testing, bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) confidence intervals were prioritized for their accuracy with skewed distributions, with statistical significance determined at p < 0.05. Effect sizes (R2) were computed to evaluate practical significance, while collinearity diagnostics (VIF < 5) confirmed predictor independence, ensuring analytical rigor across all models. This comprehensive analytical sequence systematically addressed each research question while accounting for the distinctive properties of the dataset.

5. Discussion

This study extends Trait Emotional Intelligence (TEI) theory by situating it within Pakistan’s high-pressure, teacher-centred EFL learning ecology—one marked by linguistic hybridity, punitive assessments, and hierarchical classroom dynamics. In addressing the three research questions, the findings both corroborate and challenge existing TEI literature, underscoring the need for a contextually stratified framework.

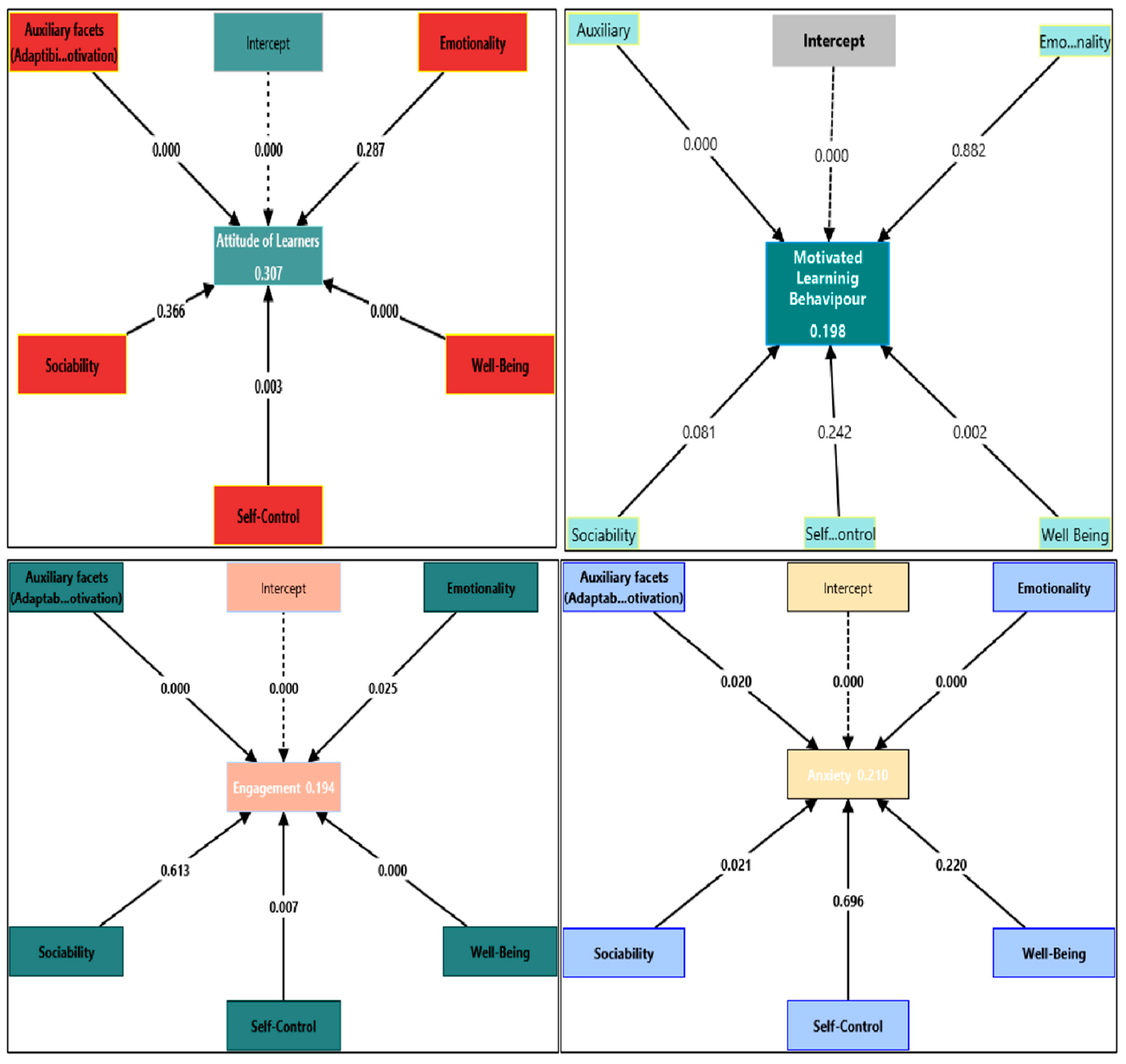

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 provide a critical visual summary of these dynamics.

Figure 1 demonstrates that TEI, treated as a unified construct, significantly predicts all four affective outcomes—attitudes, motivation, Engagement, and anxiety—reinforcing the widely supported premise that higher TEI generally corresponds with more adaptive emotional and academic functioning (

Dewaele & Li, 2021;

Fredrickson, 2001).

However,

Figure 2 complicates this picture by disaggregating TEI into its constituent components, revealing key asymmetries in predictive power and directionality that underscore the importance of cultural and contextual moderation. It displays four path analysis models examining how TEI facets predict affective outcomes in Pakistani EFL learners (N = 515). The upper left quadrant illustrates the attitude prediction model, where well-being (β = 0.172 ***), auxiliary facet (β = 0.158 ***), and self-control (β = 0.122 **) emerge as significant predictors. The upper right quadrant presents the motivation model, with auxiliary facet (β = 0.269 ***) and well-being (β = 0.219 **) demonstrating significant predictive power. The lower left quadrant shows the engagement model, revealing well-being (β = 0.179 ***) and auxiliary facet (β = 0.143 ***) as positive predictors, while emotionality (β = −0.092 *) exhibits a negative predictive relationship. The lower right quadrant depicts the anxiety model, where emotionality (β = 0.192 ***), auxiliary facet (β = 0.109 *), and sociability (β = 0.101 *) function as significant predictors. Solid connecting lines represent statistically significant pathways, while dashed lines indicate non-significant relationships. All path coefficients and significance levels align with the bootstrapped regression analyses detailed in

Table 3. Significance levels: *

p < 0.05, **

p < 0.01, ***

p < 0.001.

Consistent with global research (

Fredrickson, 2001;

Alamer & Alrabai, 2024), well-being emerged as the most stable and universal predictor of affective outcomes. It significantly enhanced learners’ attitudes (β = 0.172,

p < 0.001), motivation (β = 0.219,

p = 0.002), and engagement (β = 0.179,

p < 0.001). These findings about motivation align with

Dörnyei’s (

2009) L2 Motivational Self System, particularly the Ought-to L2 Self component, where learners’ motivation is driven by external expectations and societal pressures rather than intrinsic interest. In Pakistan’s exam-centric environment, well-being provides the emotional stability necessary to sustain motivation under external pressure, while contextual adaptability (auxiliary facet) enables learners to navigate the complex linguistic and cultural demands that characterize their Ought-to L2 Self—learning English not from personal desire but from socio-economic necessity. This pattern diverges from Western contexts where the Ideal L2 Self (intrinsic motivation) typically dominates, highlighting how Pakistan’s institutional pressures reshape the motivational landscape toward compliance-based rather than aspiration-based learning. Moreover, the finding of engagement supports Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory, which posits that emotional stability broadens learners’ cognitive scope and resourcefulness—even in resource-scarce contexts. In Pakistan’s exam-centric system, where emotional suppression and fear of failure dominate, the presence of emotional stability serves as a psychological anchor, enabling sustained learning engagement.

Unlike global findings where emotionality typically reduces anxiety and supports classroom engagement (

Chen et al., 2021;

Dewaele & MacIntyre, 2016), this study found that emotionality increased anxiety (β = 0.192,

p < 0.001) and reduced engagement (β = −β = −0.092,

p = 0.025). These results suggest that in Pakistan’s punitive classroom climate, emotional perceptiveness may intensify fear of negative evaluation—a phenomenon aligned with

Horwitz’s (

2010) theory of foreign language anxiety (FLA). Moreover, the emphasis on emotional expression embedded in TEI theory clashes with Urdu’s cultural norms of indirect, restrained affective communication (

Rahman, 2002), making emotionality a liability rather than an asset. This finding demands a culture-sensitive recalibration of the emotionality construct.

The auxiliary facet—a context-specific variable theorized as “contextual adaptability”—emerged as a strong, consistent predictor across outcomes: motivation (β = 0.269,

p < 0.001), Engagement (β = 0.143,

p < 0.001), and reduced anxiety (β = 0.109,

p = 0.020). Unlike traditional TEI models, which omit such culture-specific dimensions, our findings suggest that navigating linguistic shifts (e.g., Urdu-to-English), managing classroom power dynamics, and responding to structural constraints (e.g., rigid assessments) are emotionally intelligent behaviors within this context. This aligns with

Bronfenbrenner’s (

1979) ecological systems theory, which emphasizes the individual’s capacity to negotiate microsystemic demands. Thus, contextual adaptability must be considered a core TEI dimension in high-stakes, multilingual education systems.

Sociability, often associated with higher Engagement and positive attitudes in collectivist cultures (

X. Zhang, 2022), had no significant predictive power in the Pakistani context (attitudes: β = 0.038,

p = 0.366; Engagement: β = 0.019,

p = 0.613). This result contradicts existing collectivist models and highlights how teacher-centred pedagogy suppresses peer interaction, neutralising the value of sociability. Relationship-building skills may remain dormant in classrooms where learners have little agency and limited opportunities to collaborate or initiate dialogue.

Contrary to numerous studies identifying self-control as a key buffer against anxiety (

Chen & Zhang, 2022;

Halil, 2024), it had no significant effect in this study (β = 0.019,

p = 0.696). We hypothesize this may reflect regulatory exhaustion (

Baumeister et al., 1998): constant demands for conformity and emotional restraint in rigid classrooms deplete learners’ capacity to exert self-regulation. With impulse control required not just during language tasks but throughout the learning environment, self-control becomes saturated, losing its protective influence.

Another divergence from existing models (e.g.,

Dewaele et al., 2018;

Gardner, 1985) is the mediating role of anxiety—not attitude—in linking TEI to motivation. The indirect effect of well-being on motivation via anxiety reduction (β = 0.31,

p < 0.01) was more than twice as strong as the effect mediated by attitude. This underscores the context-specific salience of FLA in Pakistan, where English proficiency is often equated with socio-economic mobility (

Rahman, 2002;

Bashir et al., 2025), and language classrooms are characterized by performance pressure and fear of error. Learners prioritize exam success and job opportunities over integrative attitudes, rendering anxiety regulation a more crucial pathway to motivation than attitudinal orientation.

5.1. Toward a Contextually Stratified TEI Framework

Together, the visual narratives in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 reveal that treating TEI as a monolithic, universally functional construct is theoretically inadequate. While global TEI frameworks emphasize broad correlations, a disaggregated and context-sensitive lens reveals the variability and even counterproductivity of specific emotional traits under culturally specific pressures. These insights support the need for a Contextually Stratified TEI Framework, in which:

Universal functions (e.g., well-being) remain broadly beneficial;

Context-activated traits (e.g., sociability and self-control) depend on structural supports and institutional design;

Culture-sensitive dimensions (e.g., emotionality and auxiliary adaptability) vary in efficacy based on the emotional scripts and pedagogical constraints of the local environment.

5.2. Implications

To optimize language learning outcomes, emotional well-being must be positioned as a foundational component. Evidence from the study highlights that interventions like mindfulness practices, resilience journaling, and emotional regulation activities positively influence Engagement (β = 0.179) and learner attitudes (β = 0.172). Educators should embed such emotional support strategies into everyday instruction to nurture a stable affective climate.

Reframing emotionality is also critical. Rather than focusing solely on expression, training should help students identify and interpret emotions—particularly anxiety—as early warning signs. This will prepare learners with the skills to overcome emotional blockades before they hinder participation or performance. The other creative solution is using the auxiliary facet: exploiting the contextual improvisational capability of students in pedagogical drills of code-switching. These tasks enable the learners to switch between Urdu emotional discourse and English academic tasks, which promote cognitive adaptability and emotional empowerment.

Curriculum policies ought to be changed with the objective of minimizing systemic foreign language anxiety (FLA). Competency portfolios are also a far less stressful version of the replacement of high-stakes testing. At the same time, the teacher training must focus on emotionally intelligent scaffolding, techniques that help educators respond to students’ emotional needs while advancing cognitive goals. Funding support for well-being (e.g., counselling services) is essential in any low-resource institution, particularly as motivational impacts in such contexts were nearly double global norms (β = 0.219).

On the institutional level, the benefits of sociability can be enabled by reproducing the classrooms as collaborative learning pods of students. In addition, recognizing contextual adaptability as a formal graduate attribute—alongside language proficiency—can validate the emotional and cognitive skills learners bring to multilingual contexts.

Collectively, these strategies shift a fixed concept of Trait emotional intelligence (TEI) to a dynamic construct that is teachable and allows the Pakistani learners to develop emotional competence that is responsive to the local context rather than foreign standards.

5.3. Limitations

This study offers an invaluable outlook into the place of TEI in the EFL environment of Pakistan, but various limitations must be taken into consideration. The cross-sectional design denies the causal interpretations of the dynamic interactions of TEI components; they dynamically interact with affective variables at one time or another due to the fluctuating nature of language anxiety during high-stakes exam periods, especially. Furthermore, the use of self-reported questionnaires threatens social desirability bias, especially with regard to assessing sensitive constructs of anxiety in a society where expressing weaknesses is a stigmatized trait. Although being statistically significant, the unexplained auxiliary facet (AU) is theoretically undefined, and hence represents a gap in measurement in terms of capturing Pakistan-specific emotional competencies. Finally, while focusing exclusively on learners addresses a vital gap, the exclusion of teacher variables overlooks how instructor TEI shapes classroom climates that moderate student outcomes.

5.4. Directions for Future Research

The shortcomings of the work further open the door to crucial future research to explore the cultural and pedagogical applicability of Trait Emotional Intelligence (TEI) in the multilingual, exam-intensive situation, such as the one in Pakistan. Longitudinal designs, i.e., diary study or repeated measures, should also follow the protective effects of well-being and other components of TEI against anxiety across important academic transitions, considering their long-term effect under pressure. Equally crucial is grounding the auxiliary facet (AU) within Pakistan’s sociolinguistic context through mixed-methods research, starting with interviews on Urdu–English emotional code-switching and culminating in a culturally valid TEI subscale.

The emotional dynamics of teachers and learners should be investigated more closely. Multilevel modelling can be used to evaluate the relationship between teacher behaviour, specifically emotion regulation, and the emotions of students in teacher-dominated classrooms, where sociability was found to have little relevance. The interventions need to be culturally responsive and should ideally be designed and tested on their effects on emotionality and anxiety, such as the one titled “Well-Being Anchors” or the other titled “Auxiliary Adaptability Drills”.

Comparative studies across similar collectivist, exam-driven contexts—such as India and Bangladesh—can clarify how linguistic and socio-economic pressures modulate TEI. This future trajectory transforms current limitations into opportunities, positioning Pakistan as a key site for redefining TEI theory in the Global South. Co-designed interventions with local educators can bridge emotional competence with equitable, contextually grounded language learning outcomes.

6. Conclusions

This study recalibrates Trait Emotional Intelligence theory within Pakistan’s high-stakes EFL environment by directly addressing three critical research questions.

Research Question 1 asked how TEI components collectively predict Pakistani EFL learners’ affective outcomes. Well-being emerged as the most consistent predictor across attitudes (β = 0.172), motivation (β = 0.219), and engagement (β = 0.179). An emergent auxiliary facet—contextual adaptability—demonstrated strong predictive power for motivation (β = 0.269) and anxiety reduction (β = 0.109). However, emotionality increased anxiety (β = 0.192) and reduced engagement (β = −0.092), while sociability showed no significant effects, contradicting global TEI models.

Research Question 2 examined mediation pathways between TEI and learning outcomes. Anxiety—not attitude—served as the primary mediator linking well-being to motivation (β = 0.31), reflecting Pakistan’s exam-centric environment where performance pressure dominates attitudinal considerations. This finding challenges Western models that emphasize positive attitudes as motivational drivers.

Research Question 3 investigated how Pakistan’s socio-educational context moderates TEI relationships. The teacher-centered, hierarchical classroom structure neutralized sociability’s typical benefits and transformed emotionality from an asset into a liability due to punitive error correction. Conversely, the auxiliary facet—encompassing skills like Urdu–English code-switching—emerged as uniquely valuable for navigating local linguistic and institutional demands.

These findings necessitate a Contextually Stratified TEI Framework, recognizing that while well-being functions universally, other TEI dimensions operate as context-activated traits dependent on cultural and pedagogical structures. For Pakistani EFL education, this research advocates for prioritizing emotional stability, reframing emotionality as risk-detection rather than expression, and developing contextual adaptability as a formal competency. By centering learners’ lived realities over imported theoretical models, this study transforms TEI from a static personality trait into a dynamic, teachable toolkit for academic resilience in Pakistan’s evolving educational landscape.