Abstract

This mixed-methods study investigated the dispositions and motivations of 118 K-12 teachers in Abu Dhabi regarding lifelong learning. Employing a sequential explanatory design, quantitative data were collected using a validated 40-item Likert scale survey across five domains: Goal setting, Application of knowledge and skills, Self-direction and evaluation, Locating information, and Adaptable learning strategies. Results indicated a moderate overall disposition toward lifelong learning, with the highest motivation observed in Self-direction and evaluation. Significant gender differences favored male teachers across all domains. The recommendations stress the need for developing goal-setting abilities, improving information accessibility, and encouraging adaptive learning strategies through focused professional development programs.

1. Introduction

Effective pedagogical practice requires lifelong learning because education is a dynamic process in a constantly changing world. K-12 educators must engage in ongoing professional development (PD) to stay updated on curriculum developments, technological innovations, and new teaching approaches that respond to their students’ evolving needs. Lifelong learning in K-12 education extends beyond classroom instruction; it includes meaningful opportunities for teachers to develop reflective, collaborative, and adaptable teaching competencies. Continuous professional growth is essential in today’s rapidly shifting educational landscape—where innovation, equity, and student-centered approaches are prioritized.

This research adopted a sequential explanatory mixed methods approach to investigate these processes. One hundred and eighteen K-12 instructors from Abu Dhabi (UAE) completed a validated 40-question survey assessing their attitudes and motivations across five spheres of lifelong learning. Two theoretical frameworks guide this study. First among the fundamental psychological needs driving constant motivation is Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (Deci & Ryan, 1985). SDT is concerned with external and internal determinants of our behavior. All human beings possess psychological needs for relatedness (feeling connected with others), competence (feeling capable), and autonomy (feeling in control of their actions), according to SDT. These needs must be fulfilled to achieve motivation and personal well-being. Teachers who demonstrate agency and expertise by leading and assessing their PD highlight traits that illustrate SDT. Likewise, teachers with high levels of self-efficacy and autonomy use adaptive learning methods to address problems.

According to the second theoretical perspective, Expectancy-Value Theory (EVT) (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002), people are more disposed to learn when they perceive benefit in the current activity and believe they can succeed. Goal setting inside this structure shows teachers’ belief in their ability to achieve professional growth. Seeking out information is driven by the perceived usefulness of new knowledge, and applying that knowledge and skills shows motivation put into action.

This research evaluates five interrelated aspects of lifelong learning: Goal setting, Use of knowledge and skills, Self-direction and evaluation, Locating information, and Adaptive learning strategies. Goal setting refers to how proactively teachers think about planning for their PD, one of the underlying components of self-regulated learning. Reporting the use of knowledge and skills specifies how effectively teachers carry out learning in a reflective pedagogy manner. There are two aspects to Self-direction and evaluation—first, how much of the development of the teacher is self-directed, and second, to what level teachers take ownership of their development—both are important principles because the UAE is pushing for more teacher agency in their system reform. The aspect of Locating information was included to emphasize that teachers can locate, assess, and use educational supplies efficiently; this is useful in contexts where schools may have limited resources or where schools are trying to transition to more digitally focused systems. Finally, the adaptive learning strategies relate to educators’ creativity and flexibility to quickly follow the school’s and students’ evolving needs. Understanding how these competencies play out and interact in UAE schools can help to develop more focused policies for PD and lifelong learning across diverse contexts.

The following research questions guide this study:

- What are the levels of teacher motivation and disposition across the five domains of lifelong learning (Goal setting, Application of knowledge and skills, Self-direction and evaluation, Locating information, and Adaptive learning strategies)?

- What correlations exist between demographic factors (gender, level of education, how many years have you been teaching) and teachers’ motivation for participation in life-long learning opportunities?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual Framework of Lifelong Learning

UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning (2023) characterized lifelong learning as relevant to all ages, all education levels, all contexts, and all approaches to learning. In addition to being a continuous learning process, lifelong learning incorporates three learning contexts: non-formal (i.e., workshops), formal (i.e., semester-long structured academic programs), and informal (i.e., conversations with peers or learning alone) (Mršić, 2024; Eraut, 2000). Lifelong learning enables learners to develop independent, flexible, and critical ways of learning, such that education across an individual’s life leads to both personal and social learning (Livingstone, 2012). Illeris and Ryan (2020) asserted that learners acquire knowledge across work, communities, and leisure time through reflective, flexible, and information literate ways (Bierema et al., 2025; UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, 2023). The OECD (2019) called for lifelong learning to produce innovation-led economies to ensure the continued development of human capital to meet the economy’s and society’s demands. Also, from a sociocultural perspective, Billett (2010) mentioned individuals’ responsibility for lifelong learning. Jarvis’ (2009) developmental approach viewed lifelong learning as learning through experience with reflection and critical engagement. This engagement shapes personal identity while informing practice from both formal and informal learning experiences.

As governments adapt to a world where technology dominates lives, the demand for lifelong learning has increased. Accordingly, many national and international attempts have been implemented, such as the UK’s Adult Education 100, which aims to explore the history and influence of adult education and build connections with communities (Allen-Kinross, 2019), or the 2015 SkillsFuture initiative in Singapore, which has revitalized address lifelong learning back into mainstream policy to retrain the existing workforce (Sung, 2017).

These perspectives advocate for a complex understanding of lifelong learning, which considers structural, contextual, and societal aspects of how educators experience and effect change alongside personal learning. In education systems, such as the one in the UAE, where teacher agency is based on continuing professional learning, it is useful to have a more multifaceted view.

2.2. Lifelong Learning in K-12 Education

Ng (2012) explains that lifelong learning in schools is intended to develop the competencies of flexibility, critical thinking, working with others, and self-regulation. With teaching strategies like project-based learning and teacher-curated opportunities for reflection, schools open doors for growth for educators and students. Educators modify their work habits in response to challenges related to new pedagogical and technological experiences. These continuous experiences prepare teachers and students for an unpredictable future.

2.3. Teacher Competencies for Lifelong Learning

The Council of the European Union (2018) articulates several lifelong learning dispositions for educators: personal and social responsibility, pedagogical responsiveness, digital competence, communication, and civic responsibility. Educators can develop responsive and inclusive learning environments, use digital tools competently, safely, and ethically, and connect with community networks of learners (The Council of the European Union, 2018). When educators rely on these dispositions, they can create meaningful and transformative educational experiences while maintaining professional relevance.

2.4. Types of Lifelong Learning Opportunities

Although they provide deep learning, traditional PD pathways like certification and degree programs are frequently hampered by time and budgetary limitations (Desimone, 2009; Darling-Hammond, 2017). Due to their relevance and accessibility, flexible options such as webinars, social learning communities, and online courses (Coursera, EdX, Khan Academy) are becoming increasingly popular (Zamiri & Esmaeili, 2024; Chen, 2021; Garet et al., 2001). Also, thanks to emerging technologies, personal PD can now be experienced via mobile applications, AI tools, and micro-credentials (Díaz-Redondo et al., 2021; Yaseen et al., 2025), allowing teachers to embark on their own learning journeys and to develop digital fluency.

2.5. Teacher Motivations and Barriers

Both internal and external factors influence participation in lifelong learning for teachers. The SDT (Deci & Ryan, 1985) identifies relatedness, competence, and autonomy as important learning features. When teachers perceive they have some level of competence and control, they are more likely to sustain learning behaviors. The EVT (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002) also builds on the perceived value of a task (whether it is intrinsic, utility, and/or identity value) and beliefs about the chances of success (expectancy) to explain motivation. Research suggests that educators motivated to learn or advance are likely providers of PD and will seek more PD (Abdullah et al., 2023; Mršić, 2024).

A number of factors influencing teachers’ continuous learning have been determined by studies, as demonstrated in Table 1:

Table 1.

Factors influencing teachers’ lifelong learning.

Teachers have a vital role to play in teaching lifelong learners. Therefore, there is a need to research teachers’ perceptions regarding the lifelong learning process and how it can be proactively improved.

2.6. Demographic Correlates of Participation

Studies indicate that factors like gender, teaching experience, and the location of schools play a significant role in how engaged students are in lifelong learning. Participation in reading and collaborative learning communities is frequently higher among female teachers (Ayanoglu & Guler, 2021; Yu & Chao, 2023). Stronger self-awareness and more specific learning objectives are characteristics of more seasoned educators (Evans, 2019; Hursen, 2016). Not all research concurs; Demir-Basaran and Sesli (2019) and Cetin and Cetin (2017) discovered conflicting trends according to gender, academic field (Joseph & Uzondu, 2024), and experiences with personal growth. Compared to their urban counterparts, teachers in rural areas have more difficulty getting access (Şahin et al., 2024; Gaikhorst et al., 2015).

Lack of support, time constraints, and resource limitations are examples of institutional and systemic barriers (Eroglu & Kaya, 2021). On the other hand, collaborative opportunities, leadership support, and a positive school culture all increase engagement (Perry & Booth, 2024). These findings suggest that the environment within organizations and individuals’ personal traits (Usta, 2023) play a crucial role in fostering sustainable lifelong learning.

2.7. Implications for Policy and Practice

To promote lifelong learning, policy frameworks should focus on eliminating systemic barriers and supporting flexible, relevant PD opportunities. Engagement can be raised through micro-credentialing, scheduled PD, and acknowledging informal learning (Zepeda, 2019; Erickson, 2019; Peters et al., 2018). Equity gaps can be closed by providing mentorship and accessible digital platforms to underserved groups (Powers et al., 2020; Callahan, 2016). Additionally, incentives like salary increases, reduced workloads, or career progression are motivating (Darling-Hammond, 2017; Philipsen, 2019).

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study adopted a cross-sectional, explanatory, sequential mixed-methods design to investigate Abu Dhabi K-12 teachers’ perspectives on lifelong learning. In the first (quantitative) phase, a structured online survey was administered to collect numerical data on teachers’ dispositions and motivations for lifelong learning and key demographic and contextual variables. The survey had a 40-item motivational scale used to generate descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations) and to test relationships and group differences via inferential analyses (e.g., MANOVA, t-tests, ANOVA, Pearson and Spearman correlations, Cronbach’s alpha, and multi-group confirmatory factor analysis).

In the second (qualitative) phase, open-ended responses from the demographic section were subjected to summative content analysis. After translating responses from Arabic into English, the research team coded word usage patterns to enrich and contextualize the quantitative findings. Qualitative analysis was performed on the survey findings to provide a more detailed understanding of the factors influencing teachers’ attitudes towards lifelong learning. This enabled the interpretation and explanation of statistical trends.

The sequential mixed-methods approach facilitated (1) quantification of the prevalence and patterns of lifelong-learning dispositions among a convenience sample of 118 in-service teachers and (2) thematic exploration of participants’ reasons and motivations as expressed in their own words.

This article will present the quantitative results of the first phase.

3.2. Participants

A convenience sample of 118 teachers representing various grades and subjects responded from schools that agreed to participate. Participants actively taught during the third term of the 2023/24 academic year, and their involvement was voluntary. These teachers were invited via email to complete a survey designed to capture a broad range of viewpoints concerning lifelong learning.

3.3. Data Collection

An online survey was created to collect information about factors influencing teachers’ engagement with lifelong learning. The survey contained eleven demographic questions. The demographic section of the survey gathered background information related to gender, age, years of teaching experience, grade levels taught, subjects covered, educational background, community type where their school is located, PD opportunities, and reasons for participating in lifelong learning. Various question formats were used, including multiple-choice, multiple-response, open-ended, and scaled responses.

The survey also had a 40-item scale exploring teacher dispositions and motivations for lifelong learning. The five main categories addressed by the scale were (1) Goal setting, (2) application of knowledge and abilities, (3) Self-direction and evaluation, (4) finding information, and (5) flexible learning techniques. The data collection tool was a modified version of two lifelong learning measurement scales developed by Kirby et al. (2010) and Usta (2023). The scales were modified to match the study’s goals and research concerns. The authors of the two scales permitted modification of the scales.

To ensure consistency in the interpretation of composite scores, all negatively worded items were reverse-coded prior to analysis. Specifically, the following 14 items were identified as negatively phrased and were reverse-coded so that higher scores consistently reflected more favourable perceptions of self-directed learning: Item 3 (“I delay finding solutions, and I struggle to think critically”), Item 6 (“I rely on external guidance for learning”), Item 8 (“I prefer to learn without a structured plan”), Item 9 (“I usually approach new knowledge without considering how it connects with what I already know”), Item 14 (“I do not gather or organize resources before engaging in learning activities”), Item 16 (“ I learn difficult subjects quickly and easily’), Item 17 (“I seldom think about my own learning and progress”), Item 18 (“Individuals do not need to follow the changes in the teaching profession”), Item 21 (“I rely on external guidance for learning”), Item 22 (“I favor letting others take the lead in the learning process”), and Item 24 (“I prefer to learn without a structured plan”), Item 26 (“Continuous learning throughout all stages of life is crucial”), Item 28 (“I can locate information swiftly and efficiently whenever I need it”) and Item 33 (“I can deal with the unexpected and solve problems as they arise”). This approach allowed for the reliable aggregation of scale scores and maintained internal consistency across all measured constructs.

The survey was anonymous to preserve participants’ privacy and ensure they felt comfortable sharing their opinions. The questions were designed to be impartial and nonjudgmental to minimize any potential response bias—particularly the propensity to provide a socially acceptable answer. Both positive and negative statements were included in the survey to promote careful and comprehensive responses. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the principal investigator’s home institution.

3.4. Instrument Adaptation

This study used a 40-item adapted instrument. The instrument was adapted from two validated scales: the Lifelong Learning Scale by Kirby et al. (2010) and the Lifelong Learning Motivation Scale (LLMS) by Usta (2023). Both original scales measured lifelong learning dispositions, but the factor structures of the scales varied; Kirby et al.’s (2010) scale focused on self-directed learning behaviors, while Usta’s scale focused on streams of motivation.

To achieve the five-domain framework of the study (Goal setting, Application of knowledge and skills, Self-direction and evaluation, Locating information, and Adaptable learning strategies), items were selectively kept, changed, or added based on different criteria:

- Conceptual Relevance: Items were kept when aligned with the five domains’ theoretical constructs. For example, Kirby et al.’s (2010) items on self-regulation were assigned to “Goal setting”, while Usta’s items on intrinsic motivation were adapted for “self-direction” and “self-evaluation”.

- Linguistic and Cultural Appropriateness: Items were modified to ensure clarity and cultural relevance to the Abu Dhabi context. As an example, overt references to “career advancement” were enhanced to represent professional growth in teaching.

- Factor Structure: The 40 items included items with the original scales’ added items to cover the gaps, for example, technology use in the item “Locating information”.

Out of the 40 items used in this study, 25 were derived from previously validated instruments—12 from Kirby et al.’s (2010) Lifelong Learning Scale and 13 from Usta’s (2023) Lifelong Learning Motivation Scale. In addition to Kirby’s and Usta’s scales’ items, 15 items included in the study were developed to address conceptual areas that had not been addressed in the original scales, including attitudes towards learning with technological tools and complex viewpoints on problem-solving and self-evaluation. For example, the item “I prefer problems for which there is only one solution” was developed to examine limitations of flexible learning approaches. A comprehensive analysis at the item level, with citations of the sources of the items, their overlap status, and an explanation of the rationale for adaptations, is provided in Appendix A.

3.5. Data Analysis

The online survey responses were collected via Google Forms. Descriptive and inferential statistical analysis methods were combined to examine the data gathered from the independent variables and the scale questionnaire. The mean and standard deviation were part of the descriptive analysis. Conversely, multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs), Cronbach’s alpha, and multi-group confirmatory factor analysis were also used as examples of inferential statistical methods. The Pearson correlation coefficient and Spearman rank correlation were also used to establish relationships between the 40-item scale and independent variables. Additionally, independent samples t-test, ANOVA, or non-parametric tests like Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis (if the data is not normally distributed) were used to compare the means of Likert scale items across levels of independent variables. Tables and graphs helped to represent the results visually.

Prior to conducting the inferential statistical analyses, assumption checks were performed to ensure the appropriateness of using parametric methods such as the t-test, ANOVA, and Pearson correlation. For normality, the Shapiro–Wilk test and inspection of skewness and kurtosis values (within the acceptable range of ±1.96) were conducted. Homoscedasticity and homogeneity of variances were verified using Levene’s test for ANOVA and t-test. In the case of correlation analyses, linearity and normality assumptions were also examined through scatterplots and residual analyses. All assumptions were met at acceptable levels, justifying the use of the parametric tests reported in this study.

3.6. Statistical Standard

A 5-point Likert scale (Strongly agree = 5, agree = 4, neutral = 3, disagree = 2, Strongly disagree = 1) was employed by giving each item a score ranging from Strongly disagree to Strongly agree. The following scale was adopted to analyze the results (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Interpretation ranges for 5-point Likert scale scores based on interval calculation.

3.6.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

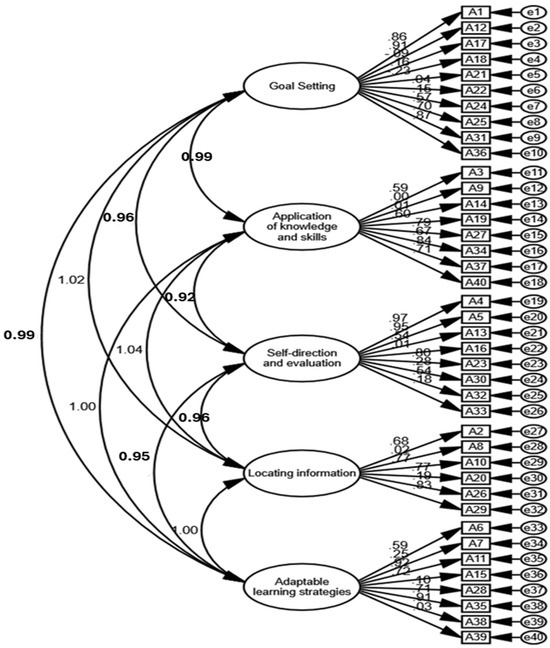

In order to assess the structural validity of the measurement model, Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted (Figure 2 and Table 2). The analysis includes key model fit indices to evaluate the overall model adequacy, in addition to standardized regression weights, which measure the extent to which each observed item contributes to its respective latent factor (F1 to F5). This step helps verify the proposed model’s internal consistency and construct validity.

Figure 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis. CMIN/DF = 3.376, GFI = 0.333, CFI = 0.519, TLI = 0.490, RMSEA = 0.173.

Table 2.

Standardized regression weights.

The model fit indices indicate that the current measurement model does not meet acceptable fit standards. The values of GFI (0.333), CFI (0.519), and TLI (0.490) fall well below the commonly accepted threshold of 0.90. Additionally, the RMSEA value (0.173) exceeds the recommended maximum of 0.08, suggesting a poor model fit. The CMIN/DF ratio (3.376) is also slightly above the acceptable range (≤3), further confirming the inadequacy of the model.

Given the poor model fit, further examination of the standardized regression weights was conducted to identify weak or problematic items. Items with factor loadings below 0.30 or negative loadings were considered weak indicators of their respective latent constructs and thus were marked for deletion to improve the model structure.

The following items were deleted due to weak or negative factor loadings:

- Factor 1 (F1): A17 (−0.090), A18 (0.157), A21 (−0.228), A22 (0.042), A24 (0.154);

- Factor 2 (F2): A9 (−0.003), A14 (0.011);

- Factor 3 (F3): A16 (0.013), A30 (0.282), A33 (0.179);

- Factor 4 (F4): A8 (0.018), A26 (0.187);

- Factor 5 (F5): A7 (0.247), A28 (0.096), A39 (0.032).

Total deleted items: 14.

These deletions aim to refine the model and improve its fit in subsequent CFA iterations. After removing the weak items, the model should be re-estimated to examine whether the overall fit improves and whether the remaining items adequately represent their respective latent factors.

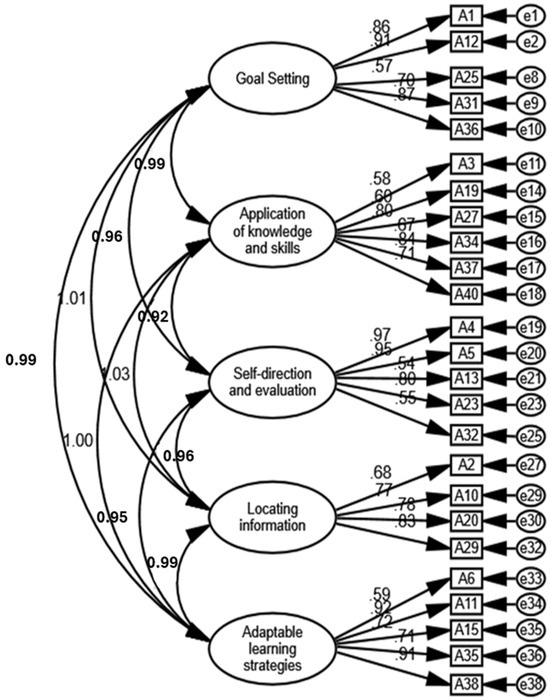

3.6.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) After Deletion of Weak Items

Following the initial CFA results, 15 items were identified as having low or negative standardized regression weights (below 0.30), indicating poor contribution to their respective latent constructs. These items were subsequently removed to improve model fit and strengthen construct validity. A second CFA was conducted on the remaining items to evaluate the improved model structure and adequacy (Figure 3 and Table 3).

Figure 3.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) after deletion of weak items. CMIN/DF = 2.838, GFI = 0.981, CFI = 0.970, TLI = 0.967, RMSEA = 0.067.

Table 3.

Standardized regression weights.

The revised CFA results indicate a substantial improvement in model fit after removing weak items. All major fit indices meet or exceed the commonly accepted thresholds, suggesting a well-fitting model:

GFI (0.981), CFI (0.970), and TLI (0.967) indicate a strong overall fit.

CMIN/DF (2.838) falls within the acceptable range, reflecting a good balance between model complexity and fit.

RMSEA (0.067) is below the threshold of 0.08, indicating an acceptable level of approximation error.

The standardized regression weights for the retained items range from 0.538 to 0.973, confirming that each observed variable contributes meaningfully to its latent construct. Most items load strongly (≥0.70), with only a few moderate (around 0.5), which are still acceptable in social science research.

The final measurement model demonstrates good construct validity and is statistically sound. It can now be used reliably for further analysis.

3.6.3. Construct Validity of the Instrument

To examine the instrument’s construct validity, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between each item and the instrument’s total score and the domain to which the item belongs. This approach is widely recognized as an effective method for evaluating construct validity, as it provides evidence of the extent to which items are theoretically aligned with the constructs they are intended to measure (Anastasi & Urbina, 1997; DeVellis, 2017).

Table 4 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients between each item and both the domain to which it belongs and the total score of the instrument. The results show that all correlations are statistically significant at either the 0.05 or 0.01 level, indicating acceptable levels of construct validity.

Table 4.

Correlation coefficients between each item, its domain, and the total score on the instrument.

According to Anastasi and Urbina (1997), significant item-domain and item-total correlations provide strong evidence that individual items are theoretically consistent with the construct the instrument aims to measure. Similarly, DeVellis (2017) emphasizes that moderate-to-high correlations suggest that items are well-aligned with their intended domains, without being redundant.

The correlation coefficients between items and their respective domains ranged from 0.37 to 0.76, while the correlations with the total instrument score ranged from 0.38 to 0.71. These results indicate that the items demonstrate a reasonable degree of internal consistency and contribute meaningfully to the domains and the overall construct being assessed.

The fact that most items exhibit moderate-to-strong correlations with both their domains and the total score supports the structural coherence of the instrument. This is in line with the criteria outlined by Cronbach and Meehl (1955), who argued that construct validity is established when the relationships among items reflect the theoretical expectations of the construct’s structure. Overall, the data provide strong evidence of the instrument’s construct validity, affirming its suitability for use in research contexts where accurate measurement of the targeted constructs is essential.

Pearson correlation coefficients were also calculated between each domain, the total score, and among the individual domains. This analysis aimed to determine the extent to which the domains are interrelated and how well they align with the overall construct being measured. The results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Correlation coefficients between the domains and the total score.

As shown in Table 5, all correlation coefficients between the individual domains and the total score and among the domains themselves are statistically significant at the 0.01 level. The strength of these correlations ranges from moderate to high, indicating strong internal consistency and coherence among the scale domains. These results provide evidence of adequate construct validity for the instrument used in the study.

3.6.4. Reliability of the Questionnaire

To assess the reliability of the research instrument (questionnaire) in terms of internal consistency and stability, two statistical measures were used:

- Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to determine the stability index by correlating the scores

- Cronbach’s Alpha was calculated from the responses to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire items within each domain.

Table 6 presents the values of Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Cronbach’s Alpha for each domain and the total questionnaire.

Table 6.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient and Cronbach’s Alpha.

As shown in Table 6, the values of the stability index (Pearson’s correlation) for the domains ranged between 0.81 and 0.87, while the overall instrument scored 0.91. The Cronbach’s Alpha values for internal consistency ranged from 0.73 to 0.84 for the individual domains and reached 0.88 for the overall instrument. These values indicate that the questionnaire possesses acceptable levels of reliability in both consistency and stability and is, therefore, appropriate for use in the current study.

4. Results

4.1. Study Sample

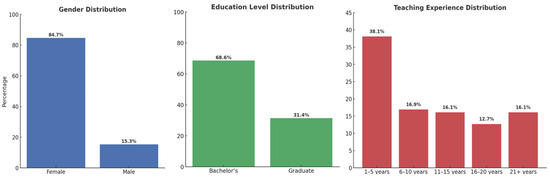

The 118 K-12 teachers in the study sample were much more female (84.7%) than male (15.3%). This gender distribution is consistent with national trends, since roughly 77% of public school instructors are female. Regarding educational attainment, 68.6% of the participants held a bachelor’s degree, while 31.4% possessed a graduate degree, such as a master’s or doctorate. This contrasts with national data indicating that over half of K-12 teachers hold a master’s degree. Regarding teaching experience, the largest group of participants (38.1%) had between 1 and 5 years of experience. The remaining participants were distributed as follows: 6–10 years (16.9%), 11–15 years (16.1%), 16–20 years (12.7%), and over 21 years (16.1%). This distribution suggests a relatively young teaching workforce within the sample, with a substantial representation of early-career educators (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Sample distribution by gender, education level, and teaching experience.

Results related to the first research question: “What are the levels of teacher motivation and disposition across the five domains of lifelong learning (Goal setting, Application of knowledge and skills, Self-direction and evaluation, Locating information, and adaptive learning strategies)?”

The means and standard deviations of the participants’ responses regarding their dispositions and motivations for engaging in lifelong learning were calculated to address the first research question. Table 7 presents the results, showing the five measured domains ranked in descending order based on their mean scores.

Table 7.

Means and standard deviations of K-12 teachers’ dispositions and motivations for participating in lifelong learning opportunities, ranked in descending order.

As shown in Table 7, the domain Self-direction and evaluation received the highest mean score (M = 3.95, SD = 0.85), indicating a high level of agreement among participants. This was closely followed by Adaptable learning strategies (M = 3.95, SD = 0.81), which also reflected a high level of agreement. Although both domains shared the same mean score, Self-direction and evaluation ranked first due to a slightly higher standard deviation.

Goal setting ranked third (M = 3.90, SD = 0.89), suggesting that participants demonstrate strong motivation in establishing personal learning goals. The domain Locating information came in fourth (M = 3.75, SD = 0.84), followed by Application of knowledge and skills in fifth place (M = 3.71, SD = 0.71); both domains also indicated a high degree of agreement.

The overall mean score across all domains was (M = 3.85, SD = 0.76), reflecting a generally high level of dispositions and motivations toward lifelong learning among the participants. While the results show strong engagement in lifelong learning behaviors across all areas, the slightly lower score in the Application of knowledge and skills domain may highlight a potential area for targeted support and professional development in real-world educational contexts.

4.2. Goal Setting

As shown in Table 8, the results related to the Goal setting domain indicate that participants demonstrated a high level of agreement with most items, reflecting strong engagement in planning and regulating their own learning processes.

Table 8.

Means and standard deviations of Goal setting items, ranked in a descending order.

The highest mean was recorded for item (1), “I like to plan my learning” (M = 4.20, SD = 1.14), suggesting that participants highly value structured and intentional learning. This was followed closely by item (12), “Individuals should adapt to changes within their career field” (M = 4.19, SD = 1.10), and item (36), “I often think about improving my learning” (M = 4.07, SD = 1.08). These responses reflect a strong orientation toward personal development and future-focused learning.

Moderate levels of agreement were observed in items such as (25), “I am a self-directed learner” (M = 3.54, SD = 1.05), and (31), “I prefer to plan my own learning” (M = 3.48, SD = 1.08). Although item (21), “I rely on external guidance for learning”, was not included in the table, its mention in the narrative suggests variability in learners’ autonomy and preference for self-regulation.

The overall mean score for the Goal setting domain was (M = 3.90, SD = 0.89), indicating a high degree of agreement among participants. These findings suggest that participants are generally proactive in setting learning goals and planning their development. However, the moderate agreement on certain items highlights the importance of supporting learners through personalized goal-setting strategies that accommodate different levels of self-directedness.

4.3. Application of Knowledge and Skills

The results for the domain Application of knowledge and skills, as illustrated in Table 9, show that participants generally exhibit a high level of agreement with the items in this category. The highest mean score was observed for item (27): “I try to relate new information with what I already know” (M = 4.05, SD = 1.18), followed closely by item (37): “Before starting learning activities, I gather and organise all resources” (M = 4.01, SD = 1.14). Both items reflect a strong tendency among participants to integrate new knowledge with prior understanding and to engage in pre-learning preparation.

Table 9.

Means and standard deviation application of knowledge and skills items, ranked in a descending order.

Additionally, item (34): “It takes time and dedication to learn difficult subjects” received a high mean score (M = 3.71, SD = 1.06), indicating recognition of the effort needed for meaningful learning. Items such as (40): “I am proactive in finding solutions and resolving issues” (M = 3.64, SD = 1.17), (3): “I delay finding solutions, and I struggle to solve issues” (M = 3.45, SD = 1.16), and (19): “I learn difficult subjects quickly and easily” (M = 3.42, SD = 0.98) were rated at a moderate level, suggesting a varied degree of confidence in participants’ problem-solving skills and learning efficiency.

Regarding the negatively worded item (3), “I delay finding solutions, and I struggle to solve issues”, which is reverse-scored, the moderate mean score indicates that participants generally disagree with the statement, reflecting a reasonably positive attitude toward timely problem-solving and effective issue resolution.

The overall mean score for this domain was (M = 3.71, SD = 0.71), indicating a high level of agreement. These findings suggest that K-12 teachers are generally effective in applying acquired knowledge and in organizing their learning resources. Nonetheless, the moderate ratings for certain items may highlight areas where participants could benefit from additional training—particularly in consistently applying strategic learning behaviors and enhancing their ability to confidently solve complex problems.

4.4. Self-Direction and Evaluation

The findings related to the Self-direction and evaluation domain, as shown in Table 10, indicate that participants generally displayed a high level of agreement with the items. The highest-rated statement was item (5), “Continuous learning throughout all stages of life is crucial” (M = 4.43, SD = 1.07), followed by item (4), “Learning new knowledge and skills contributes to my self-improvement” (M = 4.37, SD = 1.04), and item (23), “It is my responsibility to understand what I learn” (M = 4.08, SD = 1.08). These high scores suggest that participants strongly value lifelong learning and view self-directed learning as a personal responsibility.

Table 10.

Means and standard deviations of Self-direction and evaluation items, ranked in descending order.

Moderate levels of agreement were recorded for items such as (13), “Others can evaluate my success as a teacher better than I do” (M = 3.47, SD = 1.13), and (32), “I can evaluate my success as a teacher better than others” (M = 3.42, SD = 1.00), reflecting a balance between internal and external evaluation and an acknowledgment of collaborative learning processes.

The overall mean score for this domain was 3.95 (SD = 0.85), indicating a high level of agreement. These findings highlight that K-12 teachers in the sample are strongly inclined toward self-improvement and acknowledge their role in managing and evaluating their learning processes.

4.5. Locating Information

The results related to the Locating information domain, as shown in Table 11, reflect a generally high level of agreement among participants. The highest-rated item was (29), “Technological tools such as computers and mobile phones are useful to locate information” (M = 4.11, SD = 1.12), indicating a strong confidence in using digital tools for information retrieval. Similarly, item (10), “I do not hesitate to ask for help when learning something new” (M = 4.03, SD = 1.23), also received a high rating, suggesting that participants are open to seeking support during the learning process.

Table 11.

Means and standard deviations of Locating information items, ranked in descending order.

Moderate agreement was observed for item (20), “I can locate information swiftly and efficiently whenever I need it” (M = 3.63, SD = 1.03), and item (2), “I prefer learning on my own without seeking help” (M = 3.25, SD = 1.06), which may indicate a balance between independence and reliance on support systems.

The overall mean score for this domain was 3.75 (SD = 0.84), indicating a high level of agreement. These results suggest that participants generally feel capable and confident in their ability to acquire information, especially when supported by technology. Nonetheless, there remains potential to enhance their efficiency and overcome occasional obstacles in information retrieval.

4.6. Adaptable Learning Strategies

The results regarding the Adaptable learning strategies domain, as shown in Table 12, indicate a generally high level of agreement among participants (M = 3.95, SD = 0.81). The highest-rated items were (11) “I like addressing problems that present multiple solutions or allow for creative exploration” (M = 4.17, SD = 1.09) and (38) “I need to learn to keep my knowledge up-to-date and relevant continuously” (M = 4.17, SD = 1.07), both reflecting strong positive attitudes toward flexibility and ongoing learning. These findings suggest that participants embrace creativity and acknowledge the importance of continual knowledge renewal. Item (35) “I make an effort to solve problems I may encounter in my profession” (M = 3.79, SD = 1.23) and item (15) “I can deal with the unexpected and solve problems as they arise” (M = 3.73, SD = 1.10) also received high scores, reinforcing the participants’ perceived competence in managing challenges in dynamic contexts.

Table 12.

Means and standard deviations of Adaptable learning strategies items, ranked in descending order.

Among the items, the negatively worded statement (item 6), “I avoid solving problems in my profession but rather let them resolve themselves”, showed a relatively high mean score (M = 3.91, SD = 1.21). Since this item is reverse-scored, the result indicates a low level of agreement with avoiding problem-solving, reinforcing the participants’ proactive attitude toward addressing professional challenges.

In summary, the domain reflects a predominantly high level of adaptable learning behavior, demonstrating an inclination toward creativity, proactive problem-solving, and continuous professional development.

Results related to the second research question: “What correlations exist between demographic factors (gender, level of education, how many years have you been teaching) and teachers’ motivation for participation in lifelong learning opportunities?”

To examine whether there are statistically significant differences (α = 0.05) in the means of K-12 teachers’ dispositions and motivations for participating in lifelong learning opportunities based on gender, level of education, and years of teaching experience, an independent samples t-test was conducted for the variables of gender and level of education, while a one-way ANOVA was used to analyze differences based on years of teaching experience. The results are presented in Table 13, Table 14 and Table 15.

Table 13.

Independent sample t-test results for K-12 teachers’ dispositions and motivations for participating in lifelong learning opportunities by gender.

Table 14.

T-test results on K-12 teachers’ dispositions and motivations for engaging in lifelong learning opportunities according to educational level.

Table 15.

One-way ANOVA results on K-12 teachers’ dispositions and motivations for engaging in lifelong learning opportunities according to years of experience.

4.7. Years of Experience

Table 15 presents the results of a one-way ANOVA test examining whether statistically significant differences exist in K-12 teachers’ dispositions and motivations for lifelong learning based on their years of teaching experience (grouped as 1–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–20, and 21+ years). The analysis included all five subscales and the overall score.

Although there were slight variations in mean scores across experience groups, none of the differences were statistically significant (all p-values > 0.05). This suggests that years of teaching experience do not significantly impact teachers’ dispositions and motivations toward lifelong learning in this sample.

Eta squared (η2) values ranged from 0.018 to 0.043, indicating small effect sizes, meaning years of experience had a limited influence on the variables studied.

4.8. Gender

The independent samples t-test results presented in Table 13 indicate statistically significant differences (α = 0.05) between male and female K-12 teachers in their dispositions and motivations for participating in lifelong learning opportunities in several domains. Male teachers consistently demonstrated higher mean scores than their female counterparts in Goal setting (t = 2.427, p = 0.017), Application of knowledge and skills (t = 2.000, p = 0.048), Self-direction and evaluation (t = 2.277, p = 0.025), and the Overall Score (t = 2.261, p = 0.026). Although male teachers also outperformed females in Locating information and Adaptable learning strategies, the differences in these two domains did not reach statistical significance, with p-values of 0.068 and 0.062, respectively.

As measured by eta squared (η2), the effect sizes ranged from 0.004 to 0.022, which, according to Cohen’s (1988) benchmarks, represent minor effects. Despite the modest effect sizes, the consistently higher scores among male teachers suggest a gender-based trend in dispositions and motivations toward lifelong learning. These findings may have practical implications for designing professional development initiatives that aim to engage teachers equitably, with attention to gender-responsive strategies that encourage participation across all domains of lifelong learning.

4.9. Level of Education

Table 14 presents the results of an independent samples t-test examining differences in K-12 teachers’ dispositions and motivations for engaging in lifelong learning opportunities based on educational level (Bachelor’s degree vs. Graduate degree). Teachers holding a bachelor’s degree reported slightly higher mean scores across most subscales and overall scores than those with a graduate degree. However, none of the differences between the two groups reached statistical significance at the 0.05 level.

Specifically, for Goal setting, the difference was minimal (t = 0.231, p = 0.817, η2 = 0.022). Similarly, non-significant differences were found in Application of knowledge and skills (t = −0.586, p = 0.559, η2 = 0.013), Self-direction and evaluation (t = 0.381, p = 0.704, η2 = 0.004), Locating information (t = 1.148, p = 0.253, η2 = 0.001), Adaptable learning strategies (t = 0.404, p = 0.687, η2 = 0.002), and the Overall Score (t = 0.295, p = 0.769, η2 = 0.003).

The eta squared values ranged from 0.001 to 0.022, indicating small effect sizes across all domains according to Cohen’s (1988) criteria. These results suggest that educational level does not significantly influence teachers’ dispositions or motivations to engage in lifelong learning. While bachelor’s degree holders exhibited slightly higher average scores in most domains, the differences were neither statistically significant nor practically meaningful.

4.10. How Many Years Have You Been Teaching?

Table 15 presents the results of a one-way ANOVA test conducted to examine whether statistically significant differences exist in K-12 teachers’ dispositions and motivations for engaging in lifelong learning based on their years of teaching experience (categorized as 1–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–20, and 21+ years). The analysis covered five subscales—Goal Setting, Application of Knowledge and Skills, Self-direction and Evaluation, Locating Information, Adaptable Learning Strategies—and the overall score.

Although slight variations were observed in the mean scores across the different experience groups, none of the differences reached statistical significance, with all p-values greater than 0.05. For instance, the F-values ranged from 0.243 (Adaptable learning strategies) to 1.160 (Application of knowledge and skills), and all significance values (Sig.) exceeded the 0.05 threshold.

The eta squared (η2) values ranged from 0.009 to 0.027, indicating small effect sizes across all domains. According to Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, these values suggest that teaching experience had minimal influence on teachers’ dispositions and motivations for lifelong learning.

5. Discussion

This study focused on the lifelong learning dispositions and motivation of K-12 teachers in Abu Dhabi. The following two research questions guided the results’ discussion:

- What are the levels of teacher motivation and disposition across the five domains of lifelong learning (Goal setting, Application of knowledge and skills, Self-direction and evaluation, Locating information, and adaptive learning strategies)?

- What correlations exist between demographic factors (gender, level of education, how many years have you been teaching) and teachers’ motivation for participation in life-long learning opportunities?

The findings of this study provide valuable insights into the lifelong learning dispositions and motivations of K-12 teachers in Abu Dhabi across five domains: Goal setting, Application of knowledge and skills, Self-direction and evaluation, Locating information, and Adaptive learning strategies. The results showed that overall lifelong learning engagement was high (M = 3.85), suggesting that teachers favor continuing professional development.

Adaptive learning strategies and Information location had the highest mean scores (M = 4.04 and M = 3.96, respectively). Previous research has shown that successful lifelong learners are flexible, resourceful, and able to adjust their learning to fit changing conditions (Kyndt et al., 2016; OECD, 2019). These results align with those findings. This may be due to the increasing availability of digital platforms and open-access educational technologies in Abu Dhabi, which allow teachers to adapt their methods and independently search for learning materials that satisfy their professional needs.

However, Application of knowledge and skills received the lowest score (M = 3.71), indicating that although teachers are eager to learn new things, they may find applying those lessons in practical classroom settings challenging. This gap between theory and practice echoes the concerns raised in the literature regarding the limitations of one-size-fits-all professional development programs (Darling-Hammond, 2017). Without regular mentoring, feedback loops, or follow-up meetings, newly acquired skills may be wasted.

Similar to other domains, Goal setting had a comparatively low mean score (M = 3.90), indicating that teachers might profit from organised assistance in creating precise, tailored learning goals. Goal-setting is an essential metacognitive element that promotes motivation and strategic planning in adult learning, according to the self-regulated learning (SRL) theory (Zimmerman, 2013). The idea that teachers might not have the confidence or direction needed to create cohesive, long-term learning trajectories despite their initiative is further supported by the moderately rated item “I prefer to plan my own learning” (M = 3.48).

According to the inferential analysis, male teachers reported higher levels of lifelong learning than female teachers, and gender was the only demographic variable that significantly affected overall lifelong learning scores. This finding differs from studies conducted in Western contexts, where female educators typically exhibit higher levels of professional development engagement, despite the small effect size (OECD, 2019; UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, 2023). More qualitative research is required to understand this disparity, which could be caused by social obligations or culturally specific barriers that restrict female teachers’ access to professional development opportunities. However, neither teaching experience nor educational background was significantly correlated with dispositions for lifelong learning. This suggests that individual traits and possibly institutional culture influence motivation and lifelong learning more than tenure or academic success. These findings support the self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000), which emphasizes that intrinsic motivation, not credentials, drives adult learning behaviors.

6. Limitations

The study’s findings are limited by a convenience sample of 118 K-12 teachers from Abu Dhabi public schools, which may not fully represent the broader UAE teacher population. The quantitative analysis used a cross-sectional design to capture teacher dispositions and motivations, but lifelong learning tendencies are dynamic and require longitudinal research to capture these shifts. The study reveals significant gender differences in lifelong learning dispositions favoring male teachers, but the underlying causes remain unclear, requiring further investigation into sociocultural, institutional, or psychological factors. It should also be noted that the probable social desirability bias may affect self-reported Likert-scale responses. Respondents may have replied in ways that they felt were expected or appropriate in a work context, inflating their positive values of such characteristics as motivation, self-direction, or adaptability.

7. Conclusions

This study contributes to the growing body of research on teacher professional development by offering empirical evidence on lifelong learning dispositions among K-12 teachers in Abu Dhabi. Teachers demonstrated a generally high level of engagement, especially in domains requiring independent information-seeking and adaptability

The relatively lower performance in areas such as Goal-setting and Knowledge application highlights the need for structured support systems that allow teachers to set meaningful goals and turn learning into classroom action.

The statistically significant gender gap in lifelong learning engagement that favors male teachers raises important questions about equitable access to professional development opportunities and the sociocultural factors influencing the professional development of female teachers. However, the lack of significant differences by level of education and teaching experience emphasizes how crucial workplace culture and internal motivation are in encouraging lifelong learning.

Together, these findings call for the following targeted interventions:

- Promotion of tailored goal-setting frameworks in school improvement plans.

- Provision of follow-up support to ensure that newly learnt information is applied.

- Addressing gender-specific barriers to professional learning through flexible, inclusive policies.

- Promotion of a culture of self-motivation and continuous reflection following adult learning principles.

Future research could look at the qualitative experiences of teachers in creating and pursuing learning objectives, as well as the effects of institutional support networks and school leadership on lifelong learning in different educational zones in the United Arab Emirates.

8. Recommendations

Based on the study’s findings, several useful recommendations are offered to strengthen Abu Dhabi’s K-12 teachers’ dedication to lifelong learning:

- Provide goal-setting structured frameworks: Schools and educational authorities agree that professional development plans should include structured goal-setting models such as SMART goals. Educators can use these frameworks to establish individualized learning goals and monitor their progress.

- Reduce the Gap between experience and education: Professional development programs should incorporate classroom-based coaching, mentoring, and follow-up sessions to guarantee that newly acquired knowledge and skills are applied successfully. This can ensure that learning leads to improved teaching strategies.

- Encourage flexible and inclusive learning opportunities: Education policymakers should provide flexible learning formats (e.g., hybrid, asynchronous) that accommodate a range of personal and professional responsibilities to guarantee that lifelong learning programs are available to all teachers, regardless of gender.

- Encourage an intrinsic motivation culture: A learning-oriented school culture that values and encourages independent study, curiosity, and reflective practice should be fostered by school administrators. This can be accomplished by offering opportunities for cooperation, constructive criticism, and autonomy.

- Use technology to encourage lifelong learning: Delivering individualized, on-demand learning experiences that satisfy teachers’ changing needs and interests should be carried out with digital platforms and AI-powered tools, especially regarding resource discovery and adaptive learning techniques.

- Investigate gender inequalities further: To inform gender-sensitive policy and program design, researchers and educational stakeholders should investigate the root causes of the observed gender differences in lifelong learning engagement using qualitative techniques such as focus groups and interviews.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.F., J.T., A.J., O.A.K., R.H., Q.A.S., F.E.Z. and J.D.J.; Methodology, P.F., J.T., A.J., O.A.K. and J.D.J.; Validation, P.F., A.J., O.A.K., F.E.Z. and J.D.J.; Formal Analysis, P.F., J.T., A.J., O.A.K. and Q.A.S.; Investigation, R.H., Q.A.S. and F.E.Z.; Data Curation, P.F., Q.A.S. and F.E.Z.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, P.F. and J.T.; Writing—Review and Editing, P.F., J.T., R.H., F.E.Z. and J.D.J.; Visualization, Q.A.S., F.E.Z. and J.D.J.; Supervision, P.F.; Project Administration, P.F.; Funding Acquisition, P.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Emirates College for Advanced Education, grant number [GP-332-2024].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Emirates College for Advanced Education (GP-332-2024, approved on the 25 April 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Emirates College for Advanced Education for providing funding and institutional support that made this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Online Survey Scale

Demographic questions:

- How many years have you been teaching?

- (a)

- From 1 to 5 years

- (b)

- From 6 to 10 years

- (c)

- From 11 to 15 years

- (d)

- From 16 to 20 years

- (e)

- Above 20 years

- How old are you?

- (a)

- From 20 to 30 years of age

- (b)

- From 31 to 40 years of age

- (c)

- From 41 to 50 years of age

- (d)

- Above 50 years of age

- What is your gender?

- (a)

- Female

- (b)

- Male

- What is your highest level of education completed?

- (a)

- Bachelor’s degree

- (b)

- Post-graduation

- (c)

- Master’s degree

- (d)

- Doctorate

- Are you currently enrolled in any of the following programs?

- (a)

- Post-graduation

- (b)

- Master’s degree

- (c)

- Doctorate

- What grade level(s) do you currently teach? [check all that apply]

- (a)

- Kindergarten: KG1 to KG2

- (b)

- Cycle 1: grades 1 to 4

- (c)

- Cycle 2: grades 5 to 8

- (d)

- Cycle 3: grades 9 to 12

- What subject(s) do you primarily teach? [Open-ended]

- In what type of community is your school located?

- (a)

- Urban [inside a town]

- (b)

- Suburban [in the outskirts of a town]

- (c)

- Rural

- How do you access professional development opportunities? [check all that apply]

- (a)

- Face-to-face workshops

- (b)

- Online workshops

- (c)

- Face-to-face courses

- (d)

- Online courses

- (e)

- Conferences

- (f)

- Other. Please specify

- How often do you participate in professional development opportunities?

- (a)

- Weekly

- (b)

- Monthly

- (c)

- Once every trimester

- (d)

- Once every academic year

- What motivates you to engage in lifelong learning opportunities related to teaching? (Open-ended response)

Motivational scale questions:

Comparison table of the items from the Usta’s Lifelong Learning Motivation Scale (LLMS), Kirby et al.’s (2010) Lifelong Learning Scale, and the Motivational Scale Questions used in this study. The table highlights overlaps, modifications, and new additions.

Comparison of Scale Items: (✓ = Direct overlap; ~ = Modified/reworded; ✗ = Not present in original scales)

| # | This Study’s Item | Overlap/Modification | Modification Criteria & Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I like to plan my learning. | ~ | Reversed wording (direct opposite) of Kirby #1: “I prefer to have others plan my learning” |

| 2 | I prefer learning on my own without seeking help. | ~ | Contextual adaptation of Kirby #2: “I prefer problems with only one solution” (reverse-scored) |

| 3 | I delay finding solutions, and I struggle to solve issues. | ~ | Opposite meaning from Kirby #3: “I can deal with unexpected problems” (minimal linguistic modification) |

| 4 | Learning contributes to my self-improvement. | ~ | Conceptual overlap with Usta #4: “I try to learn new things daily” (contextual shift to self-improvement focus) |

| 5 | Continuous learning throughout life is crucial. | ~ | Expanded scope from Usta #5: “I focus on acquiring knowledge to achieve goals” (minimal modification) |

| 6 | I avoid solving professional problems. | ~ | Contextual adaptation of Kirby #6: “I seldom think about improving my learning” (shifted to professional context) |

| 7 | My existing knowledge is sufficient. | ~ | Opposite meaning from Usta #7: “I take opportunities to improve myself” (direct reversal) |

| 8 | I find it challenging to locate information. | ~ | Conceptual parallel to Kirby #8: “Others evaluate my success better” (contextual shift to information literacy) |

| 9 | I approach new knowledge without connections. | ~ | Linguistic modification of Kirby #9: “I love learning for its own sake” (shifted focus to knowledge integration) |

| 10 | I don’t hesitate to ask for help. | ~ | Contextual adaptation of Usta #10: “Continual learning is important” (minimal modification) |

| 11 | I like problems with multiple solutions. | ~ | Opposite meaning from Kirby #11: “I struggle to find information” (conceptual reversal) |

| 12 | Individuals should adapt to career changes. | ~ | Conceptual expansion of Kirby #12: “I relate new material to prior knowledge” (contextual shift to career adaptation) |

| 13 | Others evaluate my teaching success better. | ~ | Linguistic modification of Kirby #13: “I’m responsible for my learning” (shifted to evaluation context) |

| 14 | I don’t gather resources before learning. | ~ | Opposite meaning from Kirby #14: “I focus on details when learning” (direct reversal) |

| 15 | I can deal with unexpected problems. | ✓ | Direct adoption of Kirby #3: “I can deal with the unexpected and solve problems as they arise” |

| 16 | Learning doesn’t contribute to improvement. | ~ | Opposite meaning from Usta #4: “I try to learn new things every day” (direct reversal) |

| 17 | I seldom think about improving learning. | ✓ | Direct adoption of Kirby #6: “I seldom think about my own learning and how to improve it” |

| 18 | Don’t need to follow career field changes. | ✗ | New construct—career adaptability |

| 19 | I learn difficult subjects quickly. | ✗ | New construct—learning self-efficacy |

| 20 | I locate information efficiently. | ~ | Reverse-scored adaptation of Kirby #11: “I often find it difficult to locate information” |

| 21 | I rely on external guidance. | ~ | Conceptual parallel to Kirby #1: “I prefer to have others plan my learning” (minimal modification) |

| 22 | I let others organize my learning. | ~ | Contextual adaptation of Kirby #1: “I prefer to have others plan my learning” |

| 23 | It’s my responsibility to understand. | ✓ | Direct adoption of Kirby #13: “It is my responsibility to make sense of what I learn” |

| 24 | I prefer learning without a plan. | ~ | Alternative interpretation of Kirby #1: “I prefer to have others plan my learning” (contextual shift) |

| 25 | I am a self-directed learner. | ✓ | Direct adoption of Kirby #7: “I feel I am a self-directed learner” |

| 26 | Tech tools are ineffective for locating information. | ✗ | New construct—technology acceptance |

| 27 | I relate new info to existing knowledge. | ✓ | Direct adoption of Kirby #12: “I try to relate new material to what I already know” |

| 28 | I prefer problems with one solution. | ✓ | Direct adoption of Kirby #2: “I prefer problems for which there is only one solution” |

| 29 | Tech tools are useful for locating information. | ✗ | New construct—technology acceptance |

| 30 | I need others’ help to understand. | ~ | Linguistic modification of Kirby #1: “I prefer to have others plan my learning” |

| 31 | I prefer to plan my own learning. | ~ | Opposite meaning from Kirby #1: “I prefer to have others plan my learning” |

| 32 | I evaluate my teaching success best. | ~ | Opposite meaning from Kirby #8: “Others evaluate my success better” |

| 33 | Not necessary to learn at all life stages. | ~ | Opposite meaning from Usta #5: “Continuous learning is crucial” |

| 34 | Learning difficult subjects takes time. | ✗ | New construct—learning persistence |

| 35 | I make effort to solve work problems. | ~ | Opposite meaning from This Study #6: “I avoid solving problems” |

| 36 | I often think about improving learning. | ~ | Opposite meaning from Kirby #6: “I seldom think about improving learning” |

| 37 | I gather resources before learning. | ~ | Opposite meaning from This Study #14: “I don’t gather resources” |

| 38 | I need to keep knowledge updated. | ~ | Conceptual adaptation of Usta #5: “Continuous learning is crucial” |

| 39 | I’m uncomfortable with unexpected problems. | ~ | Opposite meaning from Kirby #3: “I can deal with unexpected problems” |

| 40 | I’m proactive in solving issues. | ~ | Opposite meaning from This Study #3: “I delay finding solutions” |

References

- Abdullah, T., Khan, M. I., Shah, S. M. U., & Ullah, S. (2023). Intrinsic and extrinsic factors affecting job satisfaction: A comparative study of public and private primary school teachers. Journal of Education and Social Studies, 4(2), 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen-Kinross, P. (2019, January 10). Lifelong learning campaigners join forces to launch ‘centenary commission’ on adult education. FeWeek. Available online: https://feweek.co.uk/lifelong-learning-campaigners-join-forces-to-launch-centenary-commission-on-adult-education/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Anastasi, A., & Urbina, S. (1997). Psychological testing (7th ed.). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Ayanoglu, C., & Guler, N. (2021). A study on the teachers’ lifelong learning competences and their reading motivation: Sapanca sample. In W. B. James, C. Cobanoglu, & M. Cavusoglu (Eds.), Advances in global education and research (1st ed., Vol. 4, pp. 1–15). USF M3 Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierema, L. L., Fedeli, M., & Merriam, S. B. (2025). Adult learning: Linking theory and practice. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Billett, S. (2010). Lifelong learning and self: Work, subjectivity and learning. Studies in Continuing Education, 32(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, J. (2016). Encouraging retention of new teachers through mentoring strategies. Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin, 83(1), 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cetin, S., & Cetin, F. (2017). Lifelong learning tendencies of prospective teachers. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(12), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C. (2021). edX offers free online courses and affordable certificates from top schools like Harvard and MIT—Here’s how it works. Business Insider. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/guides/learning/free-online-classes-edx (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Coolahan, J. (2002). Teacher education and the teaching career in an era of lifelong learning. OECD Education Working Papers No. 2. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52(4), 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher education around the world: What can we learn from international practice? European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior (1st ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir-Basaran, S., & Sesli, C. (2019). Examination of primary school and middle school teachers’ lifelong learning tendencies based on various variables. European Journal of Educational Research, 8(3), 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualisations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R. F. (2017). Scale development: Theory and applications (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Redondo, R. P., Caeiro-Rodríguez, M., López-Escobar, J. J., & Fernández-Vilas, A. (2021). Integrating micro-learning content in traditional e-learning platforms. Multimedia Tools and Applications, 20(2), 3121–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eraut, M. (2000). Non-formal learning and tacit knowledge in professional work. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70(1), 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, P. W. (2019). Micro-credentialing: A transformative tool for educator re-licensure and educator efficacy. Kansas State University. [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu, M., & Kaya, V. D. (2021). Professional development barriers of teachers: A qualitative research. International Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 13(2), 1896–1922. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, L. (2019). Implicit and informal professional development: What it ‘looks like’, how it occurs, and why we need to research it. Professional Development in Education, 45(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikhorst, L., Beishuizen, J. J., Zijlstra, B. J. H., & Volman, M. L. L. (2015). Contribution of a professional development programme to the quality and retention of teachers in an urban environment. European Journal of Teacher Education, 38(1), 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garet, M. S., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F., & Yoon, K. S. (2001). What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 38(4), 915–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B., Siu-Yung Jong, M., Tu, Y. F., Hwang, G. J., Chai, C. S., & Yi-Chao Jiang, M. (2022). Trends and exemplary practices of STEM teacher professional development programs in K-12 contexts: A systematic review of empirical studies. Computers and Education, 189, 104577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hursen, C. (2016). A scale of lifelong learning attitudes of teachers: The development of LLLAS. Cypriot Journal of Educational Sciences, 11(1), 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illeris, K., & Ryan, C. (2020). Contemporary theories of learning: Learning theorists... in their own words. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 60(1), 138–143. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, P. (2009). Learning to be a person in society. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, O. B., & Uzondu, N. C. (2024). Professional development for STEM educators: Enhancing teaching effectiveness through continuous learning. International Journal of Applied Research in Social Sciences, 6(8), 1557–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, J. R., Knapper, C., Lamon, P., & Egnatoff, W. J. (2010). Development of a scale to measure lifelong learning. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 29(3), 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyndt, E., Gijbels, D., Grosemans, I., & Donche, V. (2016). Teachers’ everyday professional development. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1111–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, D. W. (2012). Lifelong learning in paid and unpaid work. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mršić, D. (2024). 10 characteristics of 21st century learners. EPALE—Electronic platform for adult learning in Europe. Available online: https://epale.ec.europa.eu/en/blog/10-characteristics-21st-century-learners (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Ng, W. (2012). Can we teach digital natives digital literacy? Computers and Education, 59, 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2019). Getting skills right: Future-ready adult learning systems. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, E., & Booth, J. (2024). The practices of professional development facilitators. Professional Development in Education, 50(1), 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J., McMullen, B., & Peters, P. D. (2018). Professional development school experiences and culturally sustaining teaching. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 18(1), 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipsen, B. (2019). A professional development process model for online and blended learning: Introducing digital capital. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 19(4), 850–867. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, J. R., Musgrove, A. T., & Nichols, B. H. (2020). Teachers bridging the digital divide in rural schools with 1:1 computing. Rural Educator, 41(1), 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J. (2017). Lifelong learning in Singapore: Where are we? Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 37(4), 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, A., Soylu, D., & Jafari, M. B. (2024). Professional development needs of teachers in rural schools. Iranian Journal of Educational Sociology, 7(1), 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Council of the European Union. (2018). Council recommendation of 22 May 2018 on key competences for lifelong learning (pp. 1–13). Official Journal of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. (2023). Lifelong learning. Available online: https://www.uil.unesco.org/en/unesco-institute/mandate/lifelong-learning (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Usta, E. (2023). Lifelong learning motivation scale (LLMS): Validity and reliability study. Journal of Teacher Education and Lifelong Learning, 5(1), 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, H., Mohammad, A. S., Ashal, N., Abusaimeh, H., Ali, A., Sharabati, A. A., Ashal, N., Abusaimeh, H., & Ali, A. (2025). The impact of adaptive learning technologies, personalised feedback, and interactive AI tools on student engagement: The moderating role of digital literacy. Sustainability, 17(3), 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.-K., & Chao, C.-M. (2023). Encouraging teacher participation in professional learning communities: Exploring the facilitating or restricting factors that influence collaborative activities. Education and Information Technologies, 28, 5779–5804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamiri, M., & Esmaeili, A. (2024). Methods and technologies for supporting knowledge sharing within learning communities: A systematic literature review. Administrative Sciences, 14(1), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, S. J. (2019). Professional development: What works (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2013). Theories of self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview and analysis. In Self-regulated learning and academic achievement (pp. 10–45). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).