Abstract

In early childhood education (ECE), positive education is important for children’s well-being and holistic development. However, there is little research on positive education in ECE, and kindergarten teachers lack the knowledge and training for its implementation. Digital storytelling is a novel and child-friendly teaching approach that can be applied in different learning domains. Our study aimed to design a digital storytelling workshop for kindergarten teachers to equip them with digital storytelling skills that could be applied in positive education. A total of 15 teachers from a Hong Kong kindergarten participated in this digital storytelling online professional development program through the Zoom and Padlet platforms. We used the observation method to capture teachers’ perceptions, dialogues, and behaviors, collecting a total of 300 min of activity videos, researchers’ field notes, teachers’ storyboards, final videos, and reflections on Padlet for the data analysis. Based on a thematic analysis, we found that teachers had positive feelings about this digital storytelling workshop, believing that it improved their digital storytelling skills and facilitated their provision of positive education and other activities. This study contributes to the development of positive education and digital storytelling, highlighting the necessity of online professional development and providing effective strategies for ECE practitioners.

1. Introduction

Early childhood is a critical period for children’s learning and growth, during which their brain, mental, and physical development, including their cognitive, language, emotional, and social development, are consistent with psychological development theories (Berk, 2015; Bodrova & Leong, 2024). In the early years, it is vital for children to experience positive education, which refers to the application of positive psychology in educational contexts (Kristjánsson, 2012). The components of positive education consist of developing children’s well-being, social–emotional skills, character strengths, and growth mindset (Noble & McGrath, 2015; Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Seligman, 2011). Although the kindergarten curriculum contains elements of positive education, pre-service and in-service kindergarten teachers receive little training in this field (Sandholm et al., 2023). As a result, they have only a limited understanding of the concepts and pedagogies used in positive education.

Digital storytelling, as a new teaching method, is defined as the use of technology and various other means (e.g., text, video, and music) to provide opportunities for children to gain more knowledge from educational content (Robin, 2008; Smeda et al., 2014). Storytelling has been found to be an effective tool for fostering positive behaviors and emotions in children to improve their well-being (Arslan et al., 2022; Ramamurthy et al., 2024). A systematic review by Ramamurthy et al. (2024) illustrated the importance of storytelling in fostering the development of children’s protective factors, such as resilience, and revealed various specific methods, including selecting stories for children to use in identifying different psychological factors (Milaré et al., 2021), using journal logs to share and discuss ideas (Abi Zeid Daou et al., 2022), and choosing several stories about solving various difficulties (Theron et al., 2017). Similarly, digital storytelling also has similar advantages in promoting children’s well-being. Sarıca (2023) claimed that the process of digital storytelling allows children to express emotions and connect them with the story content. Specifically, Liu et al. (2018) found that digital storytelling created a social environment during English activities in which students showed happiness and better academic performance.

However, Leung et al.’s (2024) study observed and analyzed Hong Kong pre-service ECE teachers’ digital storytelling behaviors and conducted focus group interviews based on the technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) framework, finding that teachers were more familiar with telling stories and the use of technology, but they found employing digital technology for teaching to be more challenging. Thus, teachers had a need for professional development (PD). Teacher professional development (TPD) refers to teachers’ learning, including their learning of how to learn, and the transfer of their knowledge into practices that are supportive of student development (Sancar et al., 2021). Teacher professional development is significant in terms of increasing teachers’ knowledge and instructional strategies, enabling them to offer students more learning opportunities and a high-quality curriculum (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017).

In the Hong Kong context, since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in January 2020, a slogan has been spreading in K-12 education: “stop schooling but not stop learning”, and Zoom has become the main online teaching platform (Leung et al., 2021). While kindergarten teachers are familiar with storytelling and have begun to accumulate some experience in Zoom teaching, there has been an increased demand for digital teaching training among in-service teachers, leading to a growing emphasis on digital storytelling pedagogy. Therefore, this study aimed to provide online professional development (OPD) for Hong Kong kindergarten teachers regarding digital storytelling, enabling the teachers to master digital storytelling skills and apply them in positive education to promote children’s holistic development. To better understand the concepts and existing research in this field, the following sections will elaborate on positive education and its implementation in early childhood education, digital storytelling, and teacher professional development.

2. Positive Education in Early Childhood Education (ECE)

Based on the development of positive psychology, positive education is considered to be education that involves teaching traditional school skills and enhancing happiness and well-being (Noble & McGrath, 2015; Seligman et al., 2009). In traditional education, especially in Asian countries, students’ academic performance is often prioritized over the development of other skills or physical and mental health. However, with the decline in students’ mental health and the promotion of holistic education, students’ well-being has become increasingly emphasized (Canning et al., 2017; Hossain et al., 2022). To enhance students’ abilities to flourish, a PERMA model of well-being was developed, consisting of five core elements: positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment (Kern et al., 2015; Seligman, 2011). Previous studies have demonstrated that students with positive emotions, strong social relationships, and sufficient confidence have higher well-being, contributing to their academic success, mental health, and overall development (Bücker et al., 2018; Hoyt et al., 2012). As a result, positive education plays a crucial role in promoting students’ overall development.

In ECE, the development of the whole child is a core objective, emphasizing the equal importance of children’s well-being and social–emotional learning for their cognitive development (Burroughs & Barkauskas, 2017). Such content is covered in ECE programs in various countries. In Australia, the Australian Early Years Learning Framework is designed for children’s learning from the age of zero years to five years, aiming to foster children’s sustainable learning, development, and well-being (Australian Government Department of Education, 2022). In Singapore, two ECE frameworks—the Early Years Development Framework (Ministry of Social and Family Development, 2011) and Nurturing Early Learners (Ministry of Education, 2012)—emphasize children’s social–emotional and holistic development. Similarly, the Hong Kong kindergarten curriculum highlights children’s balanced development in all aspects and the nurturing of their positive values and attitudes (Curriculum Development Council, 2017).

According to a systematic review by Waters and Loton (2021), research on positive education in ECE is limited. For example, Shoshani and Slone (2017) conducted a positive education intervention program in Israel, inviting 160 children to participate and assessing the program’s effectiveness through pre- and post-tests and parent questionnaires. A group of psychologists designed this program based on the PERMA model. The results suggested that the intervention promoted children’s subjective well-being and positive learning behaviors. Although there has been little research on positive education in ECE, existing studies show that intervention programs can effectively improve children’s well-being. Therefore, positive education should be encouraged and implemented more widely in kindergartens. During this process, teachers’ competence should be highlighted.

3. Teachers’ Competence in Implementing Positive Education

To better implement positive education, many studies have conducted positive psychology interventions (PPIs; Shoshani & Slone, 2017; Shoshani & Steinmetz, 2014; Wood & Johnson, 2016). Benoit and Gabola (2021) proposed that the effectiveness of PPIs in improving students’ mental health has been proven in primary and secondary school education. However, there has been a lack of attention directed to the impact of PPIs on young children. Their review found only three studies on this topic, but all of these studies indicated that PPIs plays an important role in children’s positive development. Other meta-analytical studies have provided similar findings, supporting PPIs’ contribution to good mental health (Bolier et al., 2013; Carr et al., 2021; Seligman et al., 2009). For example, a one-year school-based PPI in Israel was shown to be effective in diminishing negative emotions and strengthening self-esteem, self-efficacy, and optimism (Shoshani & Steinmetz, 2014).

Teachers’ competence in implementing positive education depends on their knowledge and attitudes toward positive psychology, as well as their abilities to integrate PPIs into classrooms. Most existing studies have examined the effectiveness of PPIs on students, with only a small number of studies targeting teachers. Sandholm et al. (2023) explored teachers’ experiences of positive education training in Finland. The participating teachers reported that teaching positive education not only enhanced students’ social–emotional development and promoted better student–teacher relationships, but also enhanced teachers’ well-being, self-awareness, and PD. However, they encountered some challenges in conducting positive education, including a lack of time, support, and resources. Another study in Finland also provided teachers with workshops on positive education, including content such as values, well-being, and engagement. Through questionnaires and interviews, teachers reported that these trainings were extremely helpful for them in carrying out positive education, but the content was too theoretical and not practical enough, so they still needed to learn by practice (Elfrink et al., 2017). These examples underscore the importance of PD in positive education for in-service teachers.

Moreover, one of the key points of positive psychology is understanding and cultivating human virtues. Peterson and Seligman (2004) developed a framework for defining and categorizing virtues and character strengths. This framework consists of six core virtues (i.e., wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence) and 24 character strengths, classified as values in action (VIA), such as bravery, honesty, and love (Ruch et al., 2021). In our study, we adopted character strengths as the main component of positive education. Compared to other elements, the core of character strengths is often incorporated into the stories of children’s storybooks, and the content of storybooks needs to be conveyed to children through storytelling.

4. The Power of Digital Storytelling for Teaching and Learning

Storytelling has been a fundamental element of human culture and communication for thousands of years (Peck, 1989). According to Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory (Vygotsky, 1978), there is a dynamic and intertwined relationship between individuals and society. Influenced by society and individuals, storytelling begins in every family when children are young. In educational settings, conventional storytelling has been used as an effective pedagogical tool to introduce new concepts, reinforce the curriculum, and create dynamic and interactive learning environments for children (Jitsupa et al., 2022). Given the rapid development of technology, storytelling has transcended the traditional delivery of oral expression and advanced to digital performances. Digital storytelling is a creative process that mixes conventional storytelling with digital technologies, including computers, cameras, and sound recorders (Ohler, 2013). It is similar to traditional storytelling, in which students are expected to design the theme, write the script, and develop the story (O’Byrne et al., 2018). Robin (2008) proposed that there are seven elements of digital storytelling: (1) point of view, (2) dramatic questions, (3) emotional content, (4) voice/soundtrack, (5) economy, (6) pacing, and (7) multimedia integration.

Currently, digital storytelling is adopted at various educational levels, from kindergarten to college (Rahiem, 2021). Existing studies have demonstrated that digital storytelling can positively impact students’ literacy (Churchill, 2020), engagement (Liang & Hwang, 2023), learning effectiveness (Kim & Li, 2021), social–emotional learning (Sarıca, 2023), and 21st-century skills development (Kaptan & Cakir, 2024). Digital storytelling can be applied as an effective teaching method in different disciplines. For instance, an intervention study in Indonesia designed six units of digital storytelling activities that promoted children’s early literacy skills using projectors and role-play (Maureen et al., 2020). Another study in Turkey designed a design-based digital story program involving eight stories. The story structure contained narrative elements including place, time, characters, problem, solution, and outcome, which were consistent with the design process. Moreover, technology played an important role in the storytelling process. The results indicated that the design-based digital story program was effective in promoting the development of children’s computational thinking (Metin et al., 2024).

In ECE, digital storytelling has been emphasized as a child-friendly and natural way of learning (Cremin et al., 2018), which also fosters children’s holistic development and cooperation with others (Jitsupa et al., 2022; O’Byrne et al., 2018). Our study recognizes the value of digital storytelling, aiming to provide teachers with digital storytelling workshops to familiarize them with this pedagogical approach.

5. Online Teacher Professional Development

Professional development serves as an important opportunity for teachers to learn and practice both formally and informally (Avidov-Ungar et al., 2023). Formal PD is usually organized and structured through workshops, courses, and conferences conducted by experts in the field, while informal PD occurs in daily school activities, such as observing colleagues teaching and discussing with colleagues (Trust et al., 2016). Professional development is an indispensable aspect of teachers’ career paths (Avidov-Ungar et al., 2023). On the one hand, a high level of educational curriculum development places high demands on teachers’ professionalism (Darling-Hammond, 2017). On the other hand, teachers in a knowledge society have a need for new knowledge (Avidov-Ungar, 2016). Obviously, PD is an effective way to meet these two needs. To balance the requirements of the curriculum and the needs of teachers, the quality of PD needs to be ensured. High-quality and effective PD focuses on content, outcomes, and format. The content should be based on classroom practices and focus on students’ learning, while the outcomes should enhance teachers’ knowledge and pedagogies. In terms of format, PD incorporates simulations and demonstrations, active teacher learning, and the building of a professional learning community (Borko et al., 2010; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017). As such, high-quality PD needs to be provided for teachers on a regular basis to meet their needs.

Online professional development has emerged in response to the need for teacher development that fits into teachers’ busy schedules, provides access to powerful resources that are unavailable locally, and provides real-time and continuous support (Bragg et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has changed how education is delivered, resulting in the rapid growth of online learning, which has become a common approach today (Li & Lalani, 2020; Reimers et al., 2020). Online professional development consists of two modes: a synchronous mode, in which training is conducted in real time through an online platform, and an asynchronous mode of self-paced learning through online materials. A systematic review summarized 11 studies on the successful design and implementation of OPD, and found that asynchronous modes are more prevalent than synchronous modes (Bragg et al., 2021). In comparison to face-to-face PD, OPD offers a number of advantages, including flexible and diverse formats, a higher audience capacity, fewer commuting costs and less commuting time, and personalized learning (Dash et al., 2012; Powell & Bodur, 2019; Salta et al., 2022).

6. The Current Study

Based on the previous literature, it is obvious that there are limited positive education practices and studies in the context of kindergartens, and digital storytelling is considered to be a new pedagogical approach for most teachers. Compared to face-to-face PD, OPD has generated less research and practice, but it has its own unique advantages. Therefore, our study aimed to design a digital storytelling OPD program to enhance teachers’ understanding and mastery of digital storytelling and to facilitate the implementation of positive education. This program was conducted in 2022, at the tail end of the pandemic, to provide kindergarten teachers with the application of digital storytelling in online and face-to-face teaching. During the OPD program, we explored how kindergarten teachers experienced and understood the application of digital storytelling for positive education. The three specific research questions (RQs) are as follows:

RQ 1: How do kindergarten teachers experience digital storytelling?

RQ 2: How do kindergarten teachers use digital storytelling for positive education?

RQ 3: How does online professional development facilitate kindergarten teachers’ positive education through digital storytelling?

7. Materials and Methods

In response to the research questions, we adopted qualitative methods of observation and interviews to explore teachers’ dialogues, behaviors, and artwork creation during the OPD process. The following sections will describe in detail the study participants, OPD procedure, and data collection and analysis methods.

7.1. Participants

We used a nonrandomized convenience sampling strategy (Johnson & Christensen, 2010) to recruit one local kindergarten in Hong Kong. A total of 15 class teachers from three levels (K1, aged 3–4; K2, aged 4–5; K3, aged 5–6) were invited to join a one-day online digital storytelling program. Most of these teachers have bachelor’s degrees or higher and 5–10 years of teaching experience, but none of them have received technology-related training. They only have personal experience of using digital devices. During two specific hands-on workshop sessions, the teachers were divided into five groups, with three teachers each, to discuss and complete group tasks. Additionally, one researcher (second author) and two research assistants were responsible for scaffolding the groups, observing and taking field notes, and dealing with technical issues related to Zoom.

7.2. Procedure

This digital storytelling OPD program involved three parts: a lecture in the morning and two workshops in the afternoon. We used Zoom and Padlet as the OPD platforms. Details of the OPD schedule are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

OPD schedule.

7.2.1. Lecture

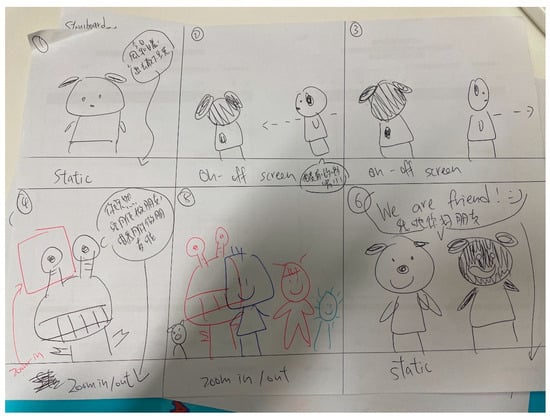

The lecture introduced the theory and practice of digital art, the techniques of digital storytelling, and the 24 character strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) in positive education. Then, there was a group discussion and videomaking practice. During the process, the researcher used a previous study (Leung et al., 2020) as an example to elaborate on knowledge of digital storytelling and explained a variety of filming techniques, including on–off screen (display or hide elements on the screen), zoom in/out (magnifying or distancing the subject), static (unmoving camera), handheld (dynamic camera movement), long take (continuous shots), and filter (stylized color/lighting). Additionally, we encouraged each group of teachers work together to practice the filming techniques so that they could master the skills. The techniques tried by the five groups were (1) on–off screen, (2) zoom in/out, (3) static, (4) handheld, and (5) long take. After that, we invited the teachers to engage in a group discussion on how they used digital technologies to tell stories during the pandemic and their perceptions of digital storytelling.

7.2.2. Workshop and Reflection

In Workshop I: Storyboard Writing, five groups of teachers had different positive value topics, such as love, honesty, and bravery to create the storyboard. The teachers in each group had to brainstorm and design a story based on the theme, draw the content in six plots, and write down the filming techniques that would be used for each plot. Workshop II: Video Making was based on the storyboards, with the teachers using different filming techniques to make a video less than two minutes long. Three teachers shared the responsibility of filming different shots and editing multiple clips into one complete video. After the lecture and the two hands-on workshops, the teachers shared their feelings, learning, and inspiration regarding this OPD on Padlet.

7.3. Data Collection and Analysis

The online digital storytelling workshop was video-recorded, and 300 min of video data were collected. In addition, we collected the teachers’ designed storyboards, final videos, and group discussions and reflections on Padlet, as well as the researchers’ field notes, to facilitate data triangulation. All the video data were transcribed, coded, and analyzed through a thematic analysis. Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns in qualitative data. Our thematic analysis consisted of six analytical phases: familiarizing ourselves with the collected data, creating initial codes, finding themes, reviewing themes, defining themes, and preparing the report (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This study was approved by the University Research Ethics Committee, and the teachers signed a consent form for voluntary participation. Their personal information was kept confidential, and the data were anonymized.

8. Findings

Guided by thematic analysis, we examined teachers’ behavior, discussions, and artwork products (including storyboards and filmed videos) to identify the following key findings corresponding to the research questions.

8.1. RQ1: Teachers’ Experience of Digital Storytelling

The teachers indicated that the pandemic was their first time attempt to teach online and to use digital storytelling; thus, they only knew a few simple techniques:

During the pandemic, I scanned the storybook to make it into PowerPoint and then sometimes asked the children to use the brush feature of Zoom to answer questions on the screen.(Teacher 1B)

In my Zoom classroom, I usually use PowerPoint and play a story video in conjunction with the use of hand puppets, and sometimes a story recording file is provided to the children.(Teacher 2C)

Moreover, as the teachers had not received professional training in digital teaching, they had limited knowledge of digital technologies; thus, they encountered many difficulties in designing activities and teaching, such as an increased workload and teacher-dominated, single-mode lessons. Teacher 4A said, “I find it difficult to use Zoom for lessons, and the teaching is mostly a one-way mode, with the teacher taking the lead and the children having less involvement.” Other teachers also encountered similar challenges:

For me, the online classes increased a very heavy workload, along with the constant IT learning. Also, younger children are easily distracted, and they struggle to sit for long periods of time during storytelling.(Teacher 3C)

At the beginning, I was nervous about teaching in Zoom, but after adapting, I felt that storytelling in Zoom lacked interaction with children. Moreover, the teaching method is quite singular and not so effective. For example, when children listen to audio files, they only listen, and it is difficult to guide them, so they fail to achieve the goal.(Teacher 2A)

Notably, some teachers changed their attitude toward digital storytelling during the training. We observed that the teachers in Group 2 initially had a negative attitude toward the digital storytelling pedagogy and its effectiveness due to their previous experiences, but trying out different filming techniques to tell stories gave them great inspiration.

Instead of the previous method of storytelling through scanning books, I mastered the application of filming techniques in teaching today, which can effectively enrich and promote children’ learning.(Teacher 2B)

8.2. RQ2: Teachers’ Use of Digital Storytelling in Positive Education

By observing and analyzing teachers’ brainstorming, discussions, and storyboard and video creation, we found that the teachers designed their digital storytelling in three main ways: character selection, content selection, and selection of filming techniques. For example, Group 1’s positive education theme was love. There are many kinds of love and many ways to represent love. The teachers used two black and white puppies available around them as the main characters and then designed story content about different colors and different kinds of animals being friends to reflect love. In the six-frame storyboard (Figure 1), they also discussed the different techniques to be used for each frame to present the movement of the characters. Moreover, using different techniques was considered to increase interest and appeal to children. The details of the digital storytelling designs are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Group 1’s six-frame storyboard.

Table 2.

Details of the digital storytelling designs.

In addition, we observed that each group took a collaborative approach to making the video, with the teachers taking different shots and then one teacher editing and merging them into a complete video. For example, in Group 4, three teachers took a shot individually using different filming techniques (Figure 2). Then, the video was edited with mobile phone software, and different sound effects were added as appropriate.

Figure 2.

Different shots in Group 4’s video.

Moreover, we noticed that the teachers made clever use of the limited resources to shoot the content that the videos were intended to express. For instance, the teachers in Group 3 used their fingers to simulate teeth for the brushing shots (Figure 3). Similarly, the teachers in Group 5 encountered the problem that the video content was not rich enough, and the time was too short:

We started with the idea of an elephant crossing a river to reflect the theme of bravery. But just filming the elephant crossing the river was too short. The researcher instructed us that we could use different filming techniques to shoot the elephant moving from one place to another. So, we ended up with a story where the elephant crosses the river to go to the supermarket and buy food to take home, which was much more informative.(Teacher 5C)

Figure 3.

Group 3’s toothbrushing shot.

8.3. RQ3: Online Professional Development of Digital Storytelling

During the OPD program, even though the researcher had shown how each technique could be used through examples, we found that most teachers did not quite understand these techniques at that point and had no idea how to apply them. This was perhaps because these filming techniques were expressed in technical jargon and appeared complicated:

When I went into each breakout room to participate in their group discussions, I found that each group was discussing what those filming techniques actually were. They would google the definition and then discuss and guess what it meant. Based on their doubts, I provided more detailed examples and instructions to help them understand the principle of the technique and successfully apply it to make videos.(Research assistant’s field notes)

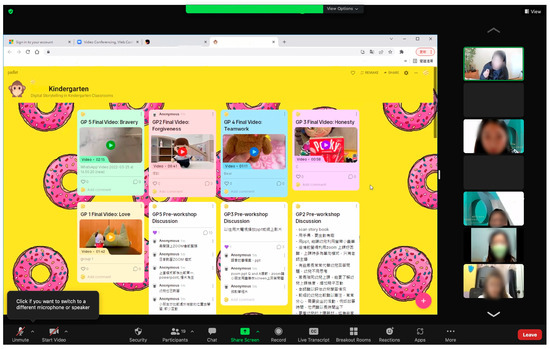

According to the format of OPD, teachers used the Zoom platform to receive knowledge and engage in oral discussions in real time, while utilizing the Padlet platform for uploading artwork and conducting text-based discussions and sharing (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Teachers’ reflections on Padlet.

On the one hand, all the teachers believed that theory–practice combined training was interesting and made it easy to acquire knowledge and skills.

I have always been so curious and interested in making videos. This online PD workshop gave me the opportunity to learn and try digital storytelling. It turns out that being a director is not easy at all, but today we can make a video in a short time!(Teacher 3A)

Through this online PD, I have learned to use different techniques for taking and editing videos as well as delivering content, such as the theme of love for positive education. I have also mastered the use of technology to enrich my teaching.(Teacher 1A)

On the other hand, some teachers pointed out that in the current digital age, this OPD provided them with flexible digital learning experiences and a fresh understanding of children’s use of technology.

Before attending this OPD, I thought that today’s training was about how to use Zoom for better teaching in the classroom. Surprisingly, face-to-face teaching can also be applied to digital storytelling techniques to make the story more interesting for children.(Teacher 4C)

Online professional development makes me feel more flexible in terms of time and format, and the training content and discussions can be saved for review later. Moreover, having participated in this workshop, I realized that when children are exposed to electronic devices, they can not only use Zoom, watch videos, and play games, but they can also try to engage in making videos to enhance their technological skills.(Teacher 5A)

9. Discussion

The findings demonstrated that the OPD program equipped kindergarten teachers with theoretical knowledge, practical skills, and hands-on opportunities to master the digital storytelling pedagogy for positive education in both online and offline teaching.

9.1. Empowering Teachers as Positive Education Practitioners

The teachers’ behaviors in making videos using the digital storytelling techniques in this workshop demonstrated how kindergarten teachers in Hong Kong are unfamiliar with the concept of positive education, but they understand the components involved, such as positive values. According to the PERMA model, the foundational framework of positive education includes positive emotion, engagement, relationships, meaning, and accomplishment (Kern et al., 2015; Seligman, 2011). Thus, the stories that they designed based on character strengths (i.e., love, forgiveness, honesty, teamwork, and bravery) expressed positive education effectively. In the Hong Kong context, the Kindergarten Education Curriculum Guide suggests that children should have balanced development, focusing on five developmental goals: ethics, intellect, physique, social skills, and aesthetics. These goals are achieved through six learning domains: physical fitness and health, language, early childhood mathematics, nature and living, self and society, and arts and creativity (Curriculum Development Council, 2017). These developmental goals and learning areas address elements of positive education and are aligned with the five dimensions of the PERMA model. Although the Guide emphasizes these developmental goals, teachers have a limited understanding of positive education, so they typically focus on observable learning domains (e.g., language, mathematics, and physical fitness) in which behaviors can be easily assessed in regular classroom settings.

Previous studies have pointed out that positive education can happen in the classroom as well as in daily routines, and that teachers should teach skills related to both children’s well-being and children’s achievement (Seligman et al., 2009; White & Murray, 2015). Teachers are the implementers of positive education. The model of our digital storytelling OPD is quite similar to an existing positive psychology training workshop (Shoshani & Slone, 2017). Their intervention program is based on the four aspects of the PERMA model, integrating the core values into children’s daily learning activities and free play, with formats including discussions, stories, games, and music. Through pre- and post-tests in the control-trial experiment, they verified a significant effect of the intervention activities on children’s well-being. Therefore, we can infer that our digital storytelling OPD program helps cultivate teachers’ ability to use digital storytelling to promote positive education. Therefore, to facilitate the practice of positive education in ECE, teachers need more training in positive education to improve their understanding of its concepts, nature, and pedagogical methods.

9.2. Digital Storytelling as a Pedagogy and Activity

The findings revealed that through this workshop, the teachers’ understanding of and competence in digital technology increased, with positive evaluations of the digital storytelling approach and confidence in its future application to teaching. In Hong Kong, most kindergarten teachers have not received technology-related training at the pre-service level. During the pandemic, teachers were forced to navigate online teaching, encountering many difficulties and finding the lessons ineffective. This supports Leung and Choi’s (2024) study showing that kindergarten teachers had limited knowledge and abilities regarding the use of digital devices. For example, they could make simple recordings with a camera, but without filming skills. Moreover, they found it difficult to apply digital technology to domain teaching. Additionally, due to their own limited knowledge, it was difficult to provide children with opportunities to use cameras, and they were concerned that they were not competent. Through this workshop, kindergarten teachers realized that digital storytelling is not a pedagogy that is only applicable to online teaching, but rather a novel, child-friendly teaching method that combines digital technology. It can leverage the advantages of digital devices in face-to-face teaching to enrich the content and increase teacher–child interaction.

Regarding traditional storytelling, many Hong Kong kindergartens’ school-based curricula are based on the use of picture books for teaching and learning, and teachers are experienced in storytelling pedagogies (Curriculum Development Council, 2017). For example, teachers used storybook activities to promote children’s language development (Hui et al., 2020; Lau & Rao, 2017) and artistic development (Huang et al., 2016; Leung, 2020). Therefore, combining digital technology and storytelling is a much-needed competence of Hong Kong kindergarten teachers, and it can further enrich their school-based curriculum.

In addition to being a teaching method for teachers, digital storytelling can be an interesting activity for children’s learning. Previous studies have indicated that digital storytelling can be adopted across various disciplines and improve the development of creativity, literacy, narrative, and thinking skills (Jitsupa et al., 2022; O’Byrne et al., 2018). Moreover, the Guide states that children should be aware of technological products and make good use of technology (Curriculum Development Council, 2017). Following this digital storytelling workshop, the teachers were empowered to use digital storytelling methods for positive education and to guide children in using digital techniques to engage in a variety of interesting activities, such as making videos, creating stop-motion animations, and drama play.

9.3. Online Learning Platform as PD

In this study, our digital storytelling workshop adopted the synchronous model of formal OPD. We used the Zoom and Padlet platforms to provide a five-hour session consisting of a lecture, workshops, discussions, and sharing. In line with the criteria for a high-quality and effective OPD (Borko et al., 2010; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017), our OPD was designed with a strong focus on the content and format of the workshops. The two themes of digital storytelling and positive education were designed based on the requirements for children’s development and teachers’ innovative approaches. The OPD program specifically encompassed (1) children’s well-being, social–emotional learning skills, and character strengths, (2) children’s digital literacy, and (3) teachers’ digital literacy and novel teaching methods.

Mulaimović et al.’s (2025) study demonstrated that participants perceived face-to-face PD as higher-quality than OPD, and that their engagement was higher. However, we designed the OPD format to take full advantage of the strengths of the online platform while compensating for its weaknesses. First, we used a lecture and workshop format, covering both theoretical knowledge and hands-on practice, providing teachers with more interaction and experiences so that they could learn by doing. Second, we adopted the Padlet platform to provide teachers with the opportunity to communicate with and learn from each other. Finaly, the content of this study concerned digital storytelling, and we aimed to develop teachers’ digital technology competence. Therefore, through the OPD, we immersed teachers in a digital teaching and learning environment so that they could learn how to apply technology in classroom practices.

10. Conclusions

Our digital storytelling OPD program explored how Hong Kong kindergarten teachers experience, understand, and practice digital storytelling techniques for positive education. The qualitative findings indicated that teachers had a positive attitude toward this training, and they had mastered the filming techniques, which they could apply to the design and implementation of positive education activities. However, although this one-day workshop provided teachers with some knowledge, skills, and inspiration, this study also had some limitations. First, the training duration was too short, which may result in a temporary impact on teachers without achieving long-term effects. Second, this study only conducted a teacher OPD workshop and did not carry out intervention activities or collect teachers’ classroom implementation data, which may affect our further understanding of the effectiveness of the training on teachers’ practices. Therefore, future research is recommended to conduct long-term TPD through a mixed-methods approach to gain a deeper understanding of teachers’ perceptions and practice of digital storytelling and positive education, and to provide effective strategies for early-childhood educators in this field.

Undoubtedly, the social distancing policies during the pandemic have driven the rapid development of online teaching, popularizing the integration of digital technology with education. As a result, digital storytelling pedagogy remains valued and applicable in the post-COVID-19 era. In conclusion, this study suggested that there is a strong need for teachers to have continuous professional learning to improve the quality and broaden the content of the curriculum. Moreover, OPD is an effective format, enabling teachers to more easily access novel content from external experts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W.L. and S.K.Y.L.; methodology, J.W.L. and S.K.Y.L.; data analysis, J.W.L. and S.K.Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W.L.; writing—review and editing, J.W.L., S.K.Y.L. and H.P.T.Y.; supervision, S.K.Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work described in this paper was fully supported by grants from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. CUHK 14617421).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (protocol code: SBRE-20-367; date of approval: 26 January 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The study data cannot be accessed for ethical reasons (i.e., protecting the participants’ identities).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the teachers for giving their time to participate in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abi Zeid Daou, K. R., Abi Zeid Daou, L. R., & Cousineau-Pérusse, M. (2022). Storytelling as a tool: A family-based intervention for newly resettled Syrian refugee children. International Journal of Social Welfare, 31(1), 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G., Yıldırım, M., Zangeneh, M., & Ak, İ. (2022). Benefits of positive psychology-based story reading on adolescent mental health and well-being. Child Indicators Research, 15(3), 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Department of Education. (2022). Belonging, being and becoming: The early years learning framework for Australia (V2.0). Australian Government Department of Education for the Ministerial Council.

- Avidov-Ungar, O. (2016). A model of professional development: Teachers’ perceptions of their professional development. Teachers and Teaching, 22(6), 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avidov-Ungar, O., Hadad, S., Shamir-Inbal, T., & Blau, I. (2023). Formal and informal professional development during different Covid-19 periods: The role of teachers’ career stages. Professional Development in Education, 51(4), 666–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, V., & Gabola, P. (2021). Effects of positive psychology interventions on the well-being of young children: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berk, L. (2015). Child development. Pearson Higher Education AU. [Google Scholar]

- Bodrova, E., & Leong, D. (2024). Tools of the mind: The Vygotskian approach to early childhood education. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G. J., Riper, H., Smit, F., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2013). Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health, 13, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borko, H., Jacobs, J., & Koellner, K. (2010). Contemporary approaches to teacher professional development. In International encyclopedia of education (pp. 548–556). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, L. A., Walsh, C., & Heyeres, M. (2021). Successful design and delivery of online professional development for teachers: A systematic review of the literature. Computers & Education, 166, 104158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, M. D., & Barkauskas, N. J. (2017). Educating the whole child: Social–emotional learning and ethics education. Ethics and Education, 12(2), 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bücker, S., Nuraydin, S., Simonsmeier, B. A., Schneider, M., & Luhmann, M. (2018). Subjective well-being and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 74, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canning, J., Denny, S., Bullen, P., Clark, T., & Rossen, F. (2017). Influence of positive development opportunities on student well-being, depression and suicide risk: The New Zealand Youth Health and Well-Being Survey 2012. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 12(2), 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A., Cullen, K., Keeney, C., Canning, C., Mooney, O., Chinseallaigh, E., & O’Dowd, A. (2021). Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(6), 749–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, N. (2020). Development of students’ digital literacy skills through digital storytelling with mobile devices. Educational Media International, 57(3), 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremin, T., Flewitt, R., Swann, J., Faulkner, D., & Kucirkova, N. (2018). Storytelling and story-acting: Co-construction in action. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 16(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curriculum Development Council. (2017). Kindergarten education curriculum guide. Government Printer.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher education around the world: What can we learn from international practice? European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S., Magidin de Kramer, R., O’Dwyer, L. M., Masters, J., & Russell, M. (2012). Impact of online professional development or teacher quality and student achievement in fifth grade mathematics. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 45(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfrink, T. R., Goldberg, J. M., Schreurs, K. M. G., Bohlmeijer, E. T., & Clarke, A. M. (2017). Positive educative programme. Health Education, 117(2), 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S., O’Neill, S., & Strnadová, I. (2022). What constitutes student well-being: A scoping review of students’ perspectives. Child Indicators Research, 16(2), 447–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, L. T., Chase-Lansdale, P. L., McDade, T. W., & Adam, E. K. (2012). Positive youth, healthy adults: Does positive well-being in adolescence predict better perceived health and fewer risky health behaviors in young adulthood? Journal of Adolescent Health, 50(1), 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Li, H., & Fong, R. (2016). Using Augmented Reality in early art education: A case study in Hong Kong kindergarten. Early Child Development and Care, 186(6), 879–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, A. N. N., Chow, B. W.-Y., Chan, E. S. M., & Leung, M.-T. (2020). Reading picture books with elements of positive psychology for enhancing the learning of English as a second language in young children. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitsupa, J., Nilsook, P., Songsom, N., Siriprichayakorn, R., & Yakeaw, C. (2022). Early childhood imagineering: A model for developing digital storytelling. International Education Studies, 15(2), 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B., & Christensen, L. (2010). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kaptan, E., & Cakir, R. (2024). The effect of digital storytelling on digital literacy, 21st century skills and achievement. Education and Information Technologies, 30(8), 11047–11071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M. L., Waters, L. E., Adler, A., & White, M. A. (2015). A multidimensional approach to measuring well-being in students: Application of the PERMA framework. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(3), 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D., & Li, M. (2021). Digital storytelling: Facilitating learning and identity development. Journal of Computers in Education, 8(1), 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjánsson, K. (2012). Positive psychology and positive education: Old wine in new bottles? Educational Psychologist, 47(2), 86–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C., & Rao, N. (2017). English vocabulary instruction in six early childhood classrooms in Hong Kong. In Literacy, storytelling and bilingualism in Asian classrooms (pp. 9–26). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S. K. Y. (2020). Teachers’ belief-and-practice gap in implementing early visual arts curriculum in Hong Kong. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 52(6), 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S. K. Y., & Choi, K. W. Y. (2024). Teachers’ perceptions of technical affordances in early visual arts education. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 32(1), 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S. K. Y., Chiu, J., & Lam, W. (2021). Online storytelling for young children during the pandemic. Childhood Education, 97(4), 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S. K. Y., Choi, K. W. Y., & Yuen, M. (2020). Video art as digital play for young children. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(2), 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S. K. Y., Yip, R. O. W., & Li, J. W. (2024). Exploring preservice ECE teachers’ TPACK through digital storytelling during the pandemic. Early Child Development and Care, 194(9–10), 1041–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., & Lalani, F. (2020, April 29). The COVID-19 pandemic has changed education forever. World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-education-global-covid19-online-digital-learning/ (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Liang, J. C., & Hwang, G. J. (2023). A robot-based digital storytelling approach to enhancing EFL learners’ multimodal storytelling ability and narrative engagement. Computers & Education, 201, 104827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K. P., Tai, S. J. D., & Liu, C. C. (2018). Enhancing language learning through creation: The effect of digital storytelling on student learning motivation and performance in a school English course. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(4), 913–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maureen, I. Y., van der Meij, H., & de Jong, T. (2020). Enhancing storytelling activities to support early (digital) literacy development in early childhood education. International Journal of Early Childhood, 52(1), 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin, Ş., Kalyenci, D., Başaran, M., Relkin, E., & Bilir, B. (2024). Design-based digital story program: Enhancing coding and computational thinking skills in early childhood education. Early Childhood Education Journal, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milaré, C. A. R., Kozasa, E. H., Lacerda, S., Barrichello, C., Tobo, P. R., & Horta, A. L. D. (2021). Mindfulness-Based versus story reading intervention in public elementary schools: Effects on executive functions and emotional health. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 576311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education. (2012). Nurturing early learners: A curriculum framework for kindergartens in Singapore. Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Social and Family Development. (2011). Early years development framework for child care centres. Ministry of Social and Family Development.

- Mulaimović, N., Richter, E., Lazarides, R., & Richter, D. (2025). Comparing quality and engagement in face-to-face and online teacher professional development. British Journal of Educational Technology, 56(1), 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, T., & McGrath, H. (2015). PROSPER: A new framework for positive education. Psychology of Well-Being, 5(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Byrne, W. I., Houser, K., Stone, R., & White, M. (2018). Digital storytelling in early childhood: Student illustrations shaping social interactions. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohler, J. B. (2013). Digital storytelling in the classroom: New media pathways to literacy, learning, and creativity (2nd ed.). Corwin Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, J. (1989). Using storytelling to promote language and literacy development. The Reading Teacher, 43(2), 138–141. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, C. G., & Bodur, Y. (2019). Teachers’ perceptions of an online professional development experience: Implications for a design and implementation framework. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahiem, M. D. H. (2021). Storytelling in early childhood education: Time to go digital. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 15(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamurthy, C., Zuo, P., Armstrong, G., & Andriessen, K. (2024). The impact of storytelling on building resilience in children: A systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 31(4), 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, F., Schleicher, A., Saavedra, J., & Tuominen, S. (2020). Supporting the continuation of teaching and learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Oecd, 1(1), 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Robin, B. R. (2008). Digital storytelling: A powerful technology tool for the 21st century classroom. Theory Into Practice, 47(3), 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruch, W., Gander, F., Wagner, L., & Giuliani, F. (2021). The structure of character: On the relationships between character strengths and virtues. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(1), 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salta, K., Paschalidou, K., Tsetseri, M., & Koulougliotis, D. (2022). Shift from a traditional to a distance learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Science & Education, 31(1), 93–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancar, R., Atal, D., & Deryakulu, D. (2021). A new framework for teachers’ professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 101, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandholm, D., Simonsen, J., Ström, K., & Fagerlund, Å. (2023). Teachers’ experiences with positive education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 53(2), 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıca, H. Ç. (2023). Emotions and digital storytelling in the educational context: A systematic review. Review of Education, 11(3), e3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. E. P., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education, 35(3), 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoshani, A., & Slone, M. (2017). Positive education for young children: Effects of a positive psychology intervention for preschool children on subjective well being and learning behaviors. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoshani, A., & Steinmetz, S. (2014). Positive psychology at school: A school-based intervention to promote adolescents’ mental health and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(6), 1289–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeda, N., Dakich, E., & Sharda, N. (2014). The effectiveness of digital storytelling in the classrooms: A comprehensive study. Smart Learning Environments, 1(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theron, L., Cockcroft, K., & Wood, L. (2017). The resilience-enabling value of African folktales: The read-me-to-resilience intervention. School Psychology International, 38(5), 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trust, T., Krutka, D. G., & Carpenter, J. P. (2016). “Together we are better”: Professional learning networks for teachers. Computers & Education, 102, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waters, L., & Loton, D. (2021). Tracing the growth, gaps, and characteristics in positive education science: A long-term, large-scale review of the field. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 774967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M. A., & Murray, A. S. (2015). Evidence-based approaches in positive education: Implementing a strategic framework for well-being in schools. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, A. M., & Johnson, J. (2016). The Wiley handbook of positive clinical psychology. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).