School Climate and Self-Efficacy Relating to University Lecturers’ Positive Mental Health: A Mediator Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

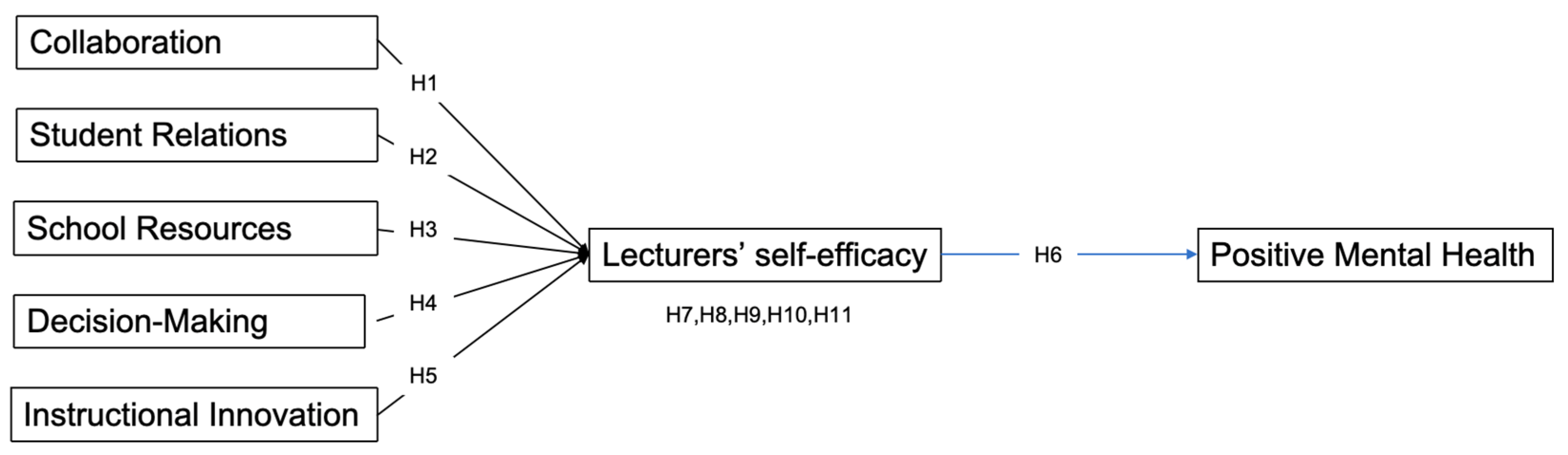

2. Literature Review

2.1. University-Level School Climate

2.2. Positive Mental Health

2.3. Lecturers’ Self-Efficacy

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. Participants and Recruitment

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Instruments

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Basic Information of the Sample

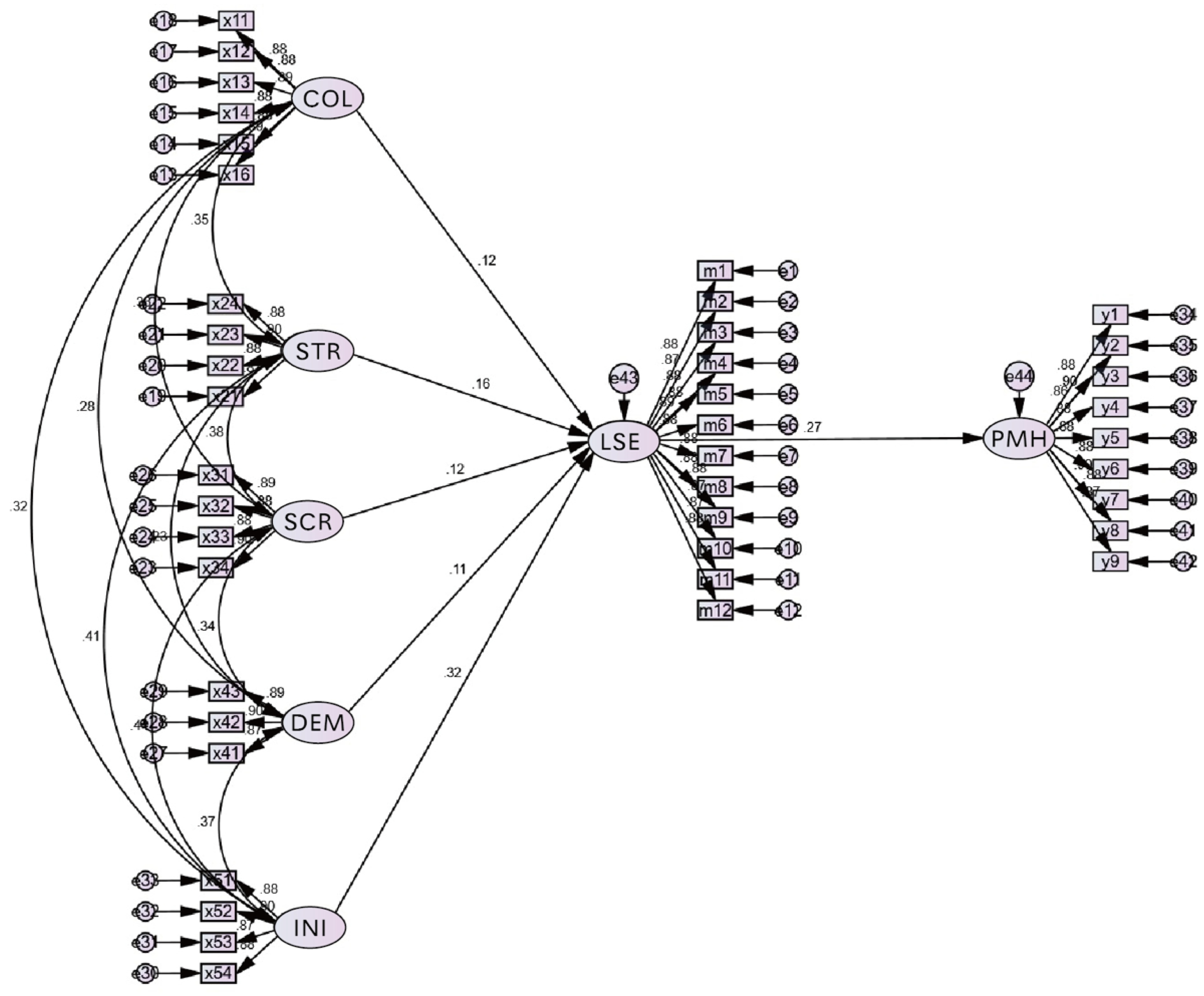

4.2. Measurement Model

4.3. Structural Model

4.4. Mediating Effects

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Implications for Policy

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LSE | Lecturers’ self-efficacy |

| COL | Collaboration |

| STR | Student Relations |

| SCR | School Resources |

| DEM | Decision-Making |

| INI | Instructional Innovation |

| PMH | Positive Mental Health |

Appendix A

| Variable | Num | Items | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Mental Health Scale | 1 | I am often carefree and in good spirits. | |

| 2 | I enjoy my life. | ||

| 3 | All in all, I am satisfied with my life. | ||

| 4 | In general, I am confident. | ||

| 5 | I manage well to fulfill my needs. | ||

| 6 | I am in good physical and emotional condition. | ||

| 7 | I feel that I am actually well equipped to deal with life and its difficulties. | ||

| 8 | Much of what I do brings me joy. | ||

| 9 | I am a calm, balanced human being. | ||

| Lecturers’ self-efficacy | 10 | How much can you do to craft good questions for students? | |

| 11 | How much can you do to implement a variety of assessment strategies? | ||

| 12 | How much can you do to provide an alternate explanation when students are confused? | ||

| 13 | How much can you do to implement alternative strategies in your classroom? | ||

| 14 | How much can you do to motivate students who show low interest in school work? | ||

| 15 | How much can you do to get students to believe they can do well in school work? | ||

| 16 | How much can you do to help students value learning? | ||

| 17 | How much can you do to assist families in helping their children do well in school? | ||

| 18 | How much can you do to control disruptive behavior in the classroom? | ||

| 19 | How much can you do to get children to follow classroom rules? | ||

| 20 | How much can you do to calm a student who is disruptive of noisy? | ||

| 21 | How much can you do to establish a classroom management system with each group of students? | ||

| School climate | Collaboration | 22 | Classroom instruction is rarely coordinated across teachers. |

| 23 | I have regular opportunities to work with other teachers. | ||

| 24 | There is good communication among teachers. | ||

| 25 | Good teamwork is not emphasized enough at my school. | ||

| 26 | I seldom discuss the needs of individual students with other teachers. | ||

| 27 | Teachers design instructional programs together | ||

| Student Relations | 28 | Most students are well mannered or respectful of the school staff. | |

| 29 | Students in this school are well behaved. | ||

| 30 | Most students are helpful and cooperative with teachers. | ||

| 31 | Most students are motivated to learn. | ||

| School Resources | 32 | The supply of equipment and resources is not adequate. | |

| 33 | Instructional equipment is not consistently accessible. | ||

| 34 | Video equipment, tapes, and films are readily available. | ||

| 35 | The school library has sufficient resources and materials | ||

| Decision-Making | 36 | Teachers are frequently asked to participate in decisions. | |

| 37 | I have very little to say in the running of the school. | ||

| 38 | Decisions about the school are made by the principal. | ||

| Instructional Innovation | 39 | We are willing to try new teaching approaches in my school. | |

| 40 | New and different ideas are always being tried out. | ||

| 41 | Teachers in this school are innovative. | ||

| 42 | New courses or curriculum materials are seldom implemented. | ||

References

- Ahmadi, S., Hassani, M., & Ahmadi, F. (2020). Student-and school-level factors related to school belongingness among high school students. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, J. M., & Fraser, B. J. (2016). Teachers’ views of their school climate and its relationship with teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction. Learning Environments Research, 19, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, M. S., Hoagwood, K. E., Kutash, K., & Seidman, E. (2010). Toward the integration of education and mental health in schools. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 37, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azila-Gbettor, E. M., & Abiemo, M. K. (2021). Moderating effect of perceived lecturer support on academic self-efficacy and study engagement: Evidence from a Ghanaian university. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 13(4), 991–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A., Freeman, W. H., & Lightsey, R. (1999). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Englewood cliffs Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bardach, L., Klassen, R. M., & Perry, N. E. (2022). Teachers’ psychological characteristics: Do they matter for teacher effectiveness, teachers’ well-being, retention, and interpersonal relations? An integrative review. Educational Psychology Review, 34(1), 259–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burić, I., Slišković, A., & Sorić, I. (2020). Teachers’ emotions and self-efficacy: A test of reciprocal relations. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buskila, Y., & Chen-Levi, T. (2021). The Role of authentic school leaders in promoting teachers’ well-being: Perceptions of israeli teachers. Athens Journal of Education, 8(2), 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, V., & Petrillo, G. (2020). Mental health in teachers: Relationships with job satisfaction, efficacy beliefs, burnout and depression. Current Psychology, 39(5), 1757–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, L., Serrão, C., Rodrigues, A. R., Marina, S., Dos Santos, J. P. M., Amorim-Lopes, T. S., Miguel, C., Teixeira, A., & Duarte, I. (2023). Burnout, resilience, and subjective well-being among Portuguese lecturers’ during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1271004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E. S., Ho, S. K., Ip, F. F., & Wong, M. W. (2020). Self-efficacy, work engagement, and job satisfaction among teaching assistants in Hong Kong’s inclusive education. Sage Open, 10(3), 2158244020941008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Collie, R. J., Shapka, J. D., & Perry, N. E. (2012). School climate and social–emotional learning: Predicting teacher stress, job satisfaction, and teaching efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlkamp, S., Peters, M., & Schumacher, G. (2017). Principal self-efficacy, school climate, and teacher retention: A multi-level analysis. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 63(4), 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallı, H. T., & Sezgin, F. (2022). Predicting teacher organizational silence: The predictive effects of locus of control, self-confidence, and perceived organizational support. Research in Educational Administration and Leadership, 7(1), 39–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathan, A. (2022). Analysis of student satisfaction in view of academic atmosphere and quality of educators. AKADEMIK: Jurnal Mahasiswa Ekonomi & Bisnis, 2(3), 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Fathi, J., & Derakhshan, A. (2019). Teacher self-efficacy and emotional regulation as predictors of teaching stress: An investigation of Iranian English language teachers. Teaching English Language, 13(2), 117–143. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N., Mahipalan, M., Poulose, S., & Burgess, J. (2022). Does gratitude ensure workplace happiness among university teachers? Examining the role of social and psychological capital and spiritual climate. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 849412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, E. (2024). Well-being and equity: A multi-disciplinary framework for rethinking education policy. In Thinking ecologically in educational policy and research (pp. 6–17). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, C., Wilcox, G., & Nordstokke, D. (2017). Teacher mental health, school climate, inclusive education and student learning: A review. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 58(3), 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Jr., Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. P. (2023). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hammoudi Halat, D., Soltani, A., Dalli, R., Alsarraj, L., & Malki, A. (2023). Understanding and fostering mental health and well-being among university faculty: A narrative review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(13), 4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harandi, T. F., Taghinasab, M. M., & Nayeri, T. D. (2017). The correlation of social support with mental health: A meta-analysis. Electronic Physician, 9(9), 5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A. F., & Scharkow, M. (2013). The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychological Science, 24(10), 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosford, S., & O’Sullivan, S. (2016). A climate for self-efficacy: The relationship between school climate and teacher efficacy for inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(6), 604–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., Yin, H., & Lv, L. (2019). Job characteristics and teacher well-being: The mediation of teacher self-monitoring and teacher self-efficacy. Educational Psychology, 39(3), 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B., Stevens, J. J., & Zvoch, K. (2007). Teachers’ perceptions of school climate: A validity study of scores from the Revised School Level Environment Questionnaire. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 67(5), 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W. B. (2015). On being a mentor: A guide for higher education faculty. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, W. (2023). Innovative school climate, teacher’s self-efficacy and implementation of cognitive activation strategies. Pegem Journal of Education and Instruction, 13(2), 126–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kaqinari, T., Makarova, E., Audran, J., Döring, A. K., Göbel, K., & Kern, D. (2022). A latent class analysis of university lecturers’ switch to online teaching during the first COVID-19 lockdown: The role of educational technology, self-efficacy, and institutional support. Education Sciences, 12(9), 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M., & Erdem, C. (2021). Students’ well-being and academic achievement: A meta-analysis study. Child Indicators Research, 14(5), 1743–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiuru, N., Wang, M.-T., Salmela-Aro, K., Kannas, L., Ahonen, T., & Hirvonen, R. (2020). Associations between adolescents’ interpersonal relationships, school well-being, and academic achievement during educational transitions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(5), 1057–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R. M., Bong, M., Usher, E. L., Chong, W. H., Huan, V. S., Wong, I. Y., & Georgiou, T. (2009). Exploring the validity of a teachers’ self-efficacy scale in five countries. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 34(1), 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, C., Wong, T. K., Persram, R. J., Vargas-Madriz, L. F., & Liu, X. (2022). Reconstructing the concept of school climate. Educational Research, 64(2), 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, S., & Naama-Ghanayim, E. (2020). Why care about caring? Linking teachers’ caring and sense of meaning at work with students’ self-esteem, well-being, and school engagement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 91, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. P. (2005). Occupational stress and mental health of Chinese teachers in 2005. Available online: https://www.lichaoping.com/ourresearch/survey/14.html (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Lukat, J., Margraf, J., Lutz, R., van der Veld, W. M., & Becker, E. S. (2016). Psychometric properties of the positive mental health scale (PMH-scale). BMC Psychology, 4, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinen, O.-P., & Savolainen, H. (2016). The effect of perceived school climate and teacher efficacy in behavior management on job satisfaction and burnout: A longitudinal study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansor, A. N., Nasaruddin, M. Z. I. M., & Hamid, A. H. A. (2021). The effects of school climate on sixth form teachers’ self-efficacy in Malaysia. Sustainability, 13(4), 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. M. (2010). Stigma and student mental health in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(3), 259–274. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M. d. M., Iaochite, R. T., & Sharp, J. G. (2022a). Lecturer self-efficacy beliefs: An integrative review and synthesis of relevant literature. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 46(2), 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M. d. M., Sharp, J. G., & Iaochite, R. T. (2022b). Self-efficacy beliefs as a predictor of quality of life and burnout among university lecturers. Frontiers in Education, 7, 887435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China. (2022). Statistical bulletin on the development of national education. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/sjzl_fztjgb/202307/t20230705_1067278.html (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Muenchhausen, S. v., Braeunig, M., Pfeifer, R., Göritz, A. S., Bauer, J., Lahmann, C., & Wuensch, A. (2021). Teacher self-efficacy and mental health—their intricate relation to professional resources and attitudes in an established manual-based psychological group program. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 510183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, S., Sohrabi, F., Afrouz, G., Delavar, A., & Hosseinian, S. (2017). Predicting the mental health of teachers based on the variables of self-efficacy and social support. Health Education and Health Promotion, 5(2), 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posselt, J., Hernandez, T. E., Villarreal, C. D., Rodgers, A. J., & Irwin, L. N. (2020). Evaluation and decision making in higher education: Toward equitable repertoires of faculty practice. In Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 35, pp. 1–63). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Raju, T. (2024). Effects of School culture on learner well-being and academic achievement. Johns Hopkins University. [Google Scholar]

- Rand, K. L., Shanahan, M. L., Fischer, I. C., & Fortney, S. K. (2020). Hope and optimism as predictors of academic performance and subjective well-being in college students. Learning and Individual Differences, 81, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, E., Dhingra, K., & Boduszek, D. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs, self-esteem, and job stress as determinants of job satisfaction. International Journal of Educational Management, 28(4), 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A. M. (2024). Instructional capacity and emotional quotient as predictors of teaching efficacy among educators in region xi heis: A convergent design. Ignatian International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research, 2(1), 551–632. [Google Scholar]

- Saienko, N., Lavrysh, Y., & Lukianenko, V. (2020). The impact of educational technologies on university teachers’ self-efficacy. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 19(6), 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, F., & Erdogan, O. (2015). Academic optimism, hope and zest for work as predictors of teacher self-efficacy and perceived success. Educational Sciences-Theory & Practice, 15(1), 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sila, E. (2023). Teachers’self-worth, leadership approaches and their influence on academic performance of secondary school learners in kakamega county, Kenya. Available online: http://41.89.195.24:8080/handle/123456789/2771 (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Smith, K. (2012). Lessons learnt from literature on the diffusion of innovative learning and teaching practices in higher education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 49(2), 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukirno, D., & Siengthai, S. (2011). Does participative decision making affect lecturer performance in higher education? International Journal of Educational Management, 25(5), 494–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R. E. (2018). Creating conditions for growth: Fostering teacher efficacy for student success. Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, L. R. (2024). The relationship among self-efficacy, teacher confidence, job satisfaction, and intention to remain in the field for urban school teachers with five years or less experience. Concordia University Chicago. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, R., & Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory of organizational management. Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiyun, S., Fathi, J., Shirbagi, N., & Mohammaddokht, F. (2022). A structural model of teacher self-efficacy, emotion regulation, and psychological wellbeing among English teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 904151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, M. A., & Mohd Matore, M. E. E. (2021). The influence of teachers’ self-efficacy and school leaders’ transformational leadership practices on teachers’ innovative behaviour. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakariya, Y. F. (2020). Effects of school climate and teacher self-efficacy on job satisfaction of mostly STEM teachers: A structural multigroup invariance approach. International Journal of STEM Education, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoer, I., Ruitenburg, M., Botje, D., Frings-Dresen, M. H., & Sluiter, J. (2011). The associations between psychosocial workload and mental health complaints in different age groups. Ergonomics, 54(10), 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | Num | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 81 | 22.689 |

| Female | 276 | 77.311 | |

| Age | ≥61 | 36 | 10.084 |

| 51–60 | 50 | 14.006 | |

| 18–30 | 69 | 19.328 | |

| 31–40 | 80 | 22.409 | |

| 41–50 | 122 | 34.174 | |

| Highest degree | Ph.D. | 29 | 8.123 |

| Master | 328 | 91.877 | |

| Institution type (Job) | Private Education | 98 | 27.451 |

| Public Education | 259 | 72.549 | |

| Variables | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSE | 1.83 | 6.58 | 5.05 | 1.55 | −1.03 | −0.82 |

| COL | 1.33 | 6.67 | 4.94 | 1.60 | −0.89 | −0.99 |

| STR | 1.50 | 7.00 | 5.16 | 1.56 | −1.15 | −0.30 |

| SCR | 1.25 | 7.00 | 4.79 | 1.74 | −0.63 | −1.37 |

| DEM | 1.00 | 7.00 | 5.15 | 1.64 | −1.15 | −0.20 |

| INI | 1.00 | 7.00 | 4.94 | 1.66 | −0.78 | −1.11 |

| PMH | 1.67 | 6.67 | 5.09 | 1.57 | −1.08 | −0.65 |

| Factor | Items | Factor Loading | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSE | LSE1 | 0.879 | 0.771 | 0.976 |

| LSE2 | 0.868 | |||

| LSE3 | 0.883 | |||

| LSE4 | 0.877 | |||

| LSE5 | 0.887 | |||

| LSE6 | 0.876 | |||

| LSE7 | 0.885 | |||

| LSE8 | 0.878 | |||

| LSE9 | 0.877 | |||

| LSE10 | 0.87 | |||

| LSE11 | 0.875 | |||

| LSE12 | 0.88 | |||

| COL | COL1 | 0.89 | 0.782 | 0.956 |

| COL2 | 0.884 | |||

| COL3 | 0.884 | |||

| COL4 | 0.885 | |||

| COL5 | 0.881 | |||

| COL6 | 0.882 | |||

| STR | STR1 | 0.866 | 0.775 | 0.933 |

| STR2 | 0.88 | |||

| STR3 | 0.898 | |||

| STR4 | 0.878 | |||

| SCR | SCR1 | 0.901 | 0.79 | 0.938 |

| SCR2 | 0.882 | |||

| SCR3 | 0.879 | |||

| SCR4 | 0.894 | |||

| DEM | DEM1 | 0.875 | 0.789 | 0.918 |

| DEM2 | 0.897 | |||

| DEM3 | 0.893 | |||

| INI | INI1 | 0.876 | 0.776 | 0.933 |

| INI2 | 0.87 | |||

| INI3 | 0.896 | |||

| INI4 | 0.882 | |||

| PMH | PMH1 | 0.878 | 0.776 | 0.969 |

| PMH2 | 0.899 | |||

| PMH3 | 0.864 | |||

| PMH4 | 0.88 | |||

| PMH5 | 0.881 | |||

| PMH6 | 0.88 | |||

| PMH7 | 0.902 | |||

| PMH8 | 0.88 | |||

| PMH9 | 0.865 |

| PMH | INI | DEM | SCR | STR | COL | LSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMH | 0.878 | ||||||

| INI | 0.290 | 0.881 | |||||

| DEM | 0.304 | 0.366 | 0.888 | ||||

| SCR | 0.289 | 0.437 | 0.343 | 0.889 | |||

| STR | 0.243 | 0.409 | 0.226 | 0.379 | 0.881 | ||

| COL | 0.152 | 0.322 | 0.281 | 0.362 | 0.345 | 0.884 | |

| LSE | 0.265 | 0.522 | 0.340 | 0.404 | 0.407 | 0.357 | 0.881 |

| β | C.R. (t-Value) | Hypothesis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | COL → LSE | 0.122 * | 2.401 | Supported |

| H2 | STR → LSE | 0.163 ** | 3.076 | Supported |

| H3 | SCR → LSE | 0.12 * | 2.19 | Supported |

| H4 | DEM → LSE | 0.11 * | 2.157 | Supported |

| H5 | INI → LSE | 0.325 *** | 5.726 | Supported |

| H6 | LSE → PMH | 0.27 *** | 5.027 | Supported |

| IV | MV | DV | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | Total Effect | VAF | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COL | LSE | PMH | 0.064 (1.205) | 0.080 * (3.330) | 0.144 * (2.892) | 55.56% | Partial mediation |

| STR | LSE | PMH | 0.154 (2.787) | 0.078 * (2.986) | 0.232 *** (4.466) | 33.62% | Partial mediation |

| SCR | LSE | PMH | 0.186 *** (3.775) | 0.062 * (2.520) | 0.248 *** (5.399) | 25.15% | Partial mediation |

| DEM | LSE | PMH | 0.217 *** (4.301) | 0.057 * (2.784) | 0.274 *** (5.645) | 20.78% | Partial mediation |

| INI | LSE | PMH | 0.185 * (3.375) | 0.075 * (2.288) | 0.260 ** (5.427) | 28.90% | Partial mediation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lai, Q.; Alias, B.S.; Hamid, A.H.A. School Climate and Self-Efficacy Relating to University Lecturers’ Positive Mental Health: A Mediator Model. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070852

Lai Q, Alias BS, Hamid AHA. School Climate and Self-Efficacy Relating to University Lecturers’ Positive Mental Health: A Mediator Model. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):852. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070852

Chicago/Turabian StyleLai, Qin, Bity Salwana Alias, and Aida Hanim A. Hamid. 2025. "School Climate and Self-Efficacy Relating to University Lecturers’ Positive Mental Health: A Mediator Model" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070852

APA StyleLai, Q., Alias, B. S., & Hamid, A. H. A. (2025). School Climate and Self-Efficacy Relating to University Lecturers’ Positive Mental Health: A Mediator Model. Education Sciences, 15(7), 852. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070852