Developing an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Framework for Student-Led Start-Ups in Higher Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Sample

3.3. Instrument Validation

3.4. Data Collection

3.5. Data Analysis

3.6. Ethical Considerations

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Statements Based on Agreement Scores

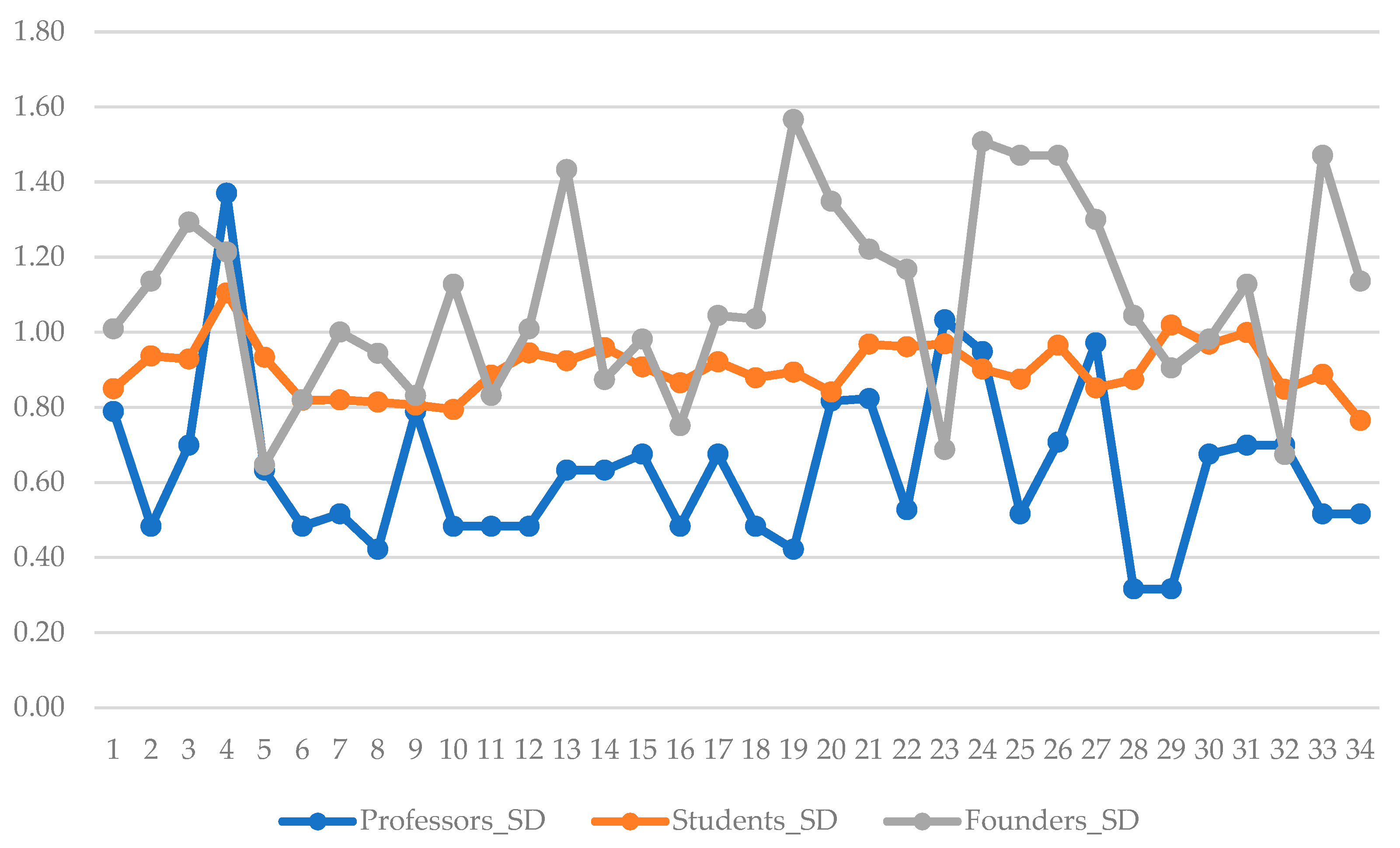

4.2. Analysis of Statements Based on Standard Deviation

4.3. Comparative Analysis Among Three Different Groups

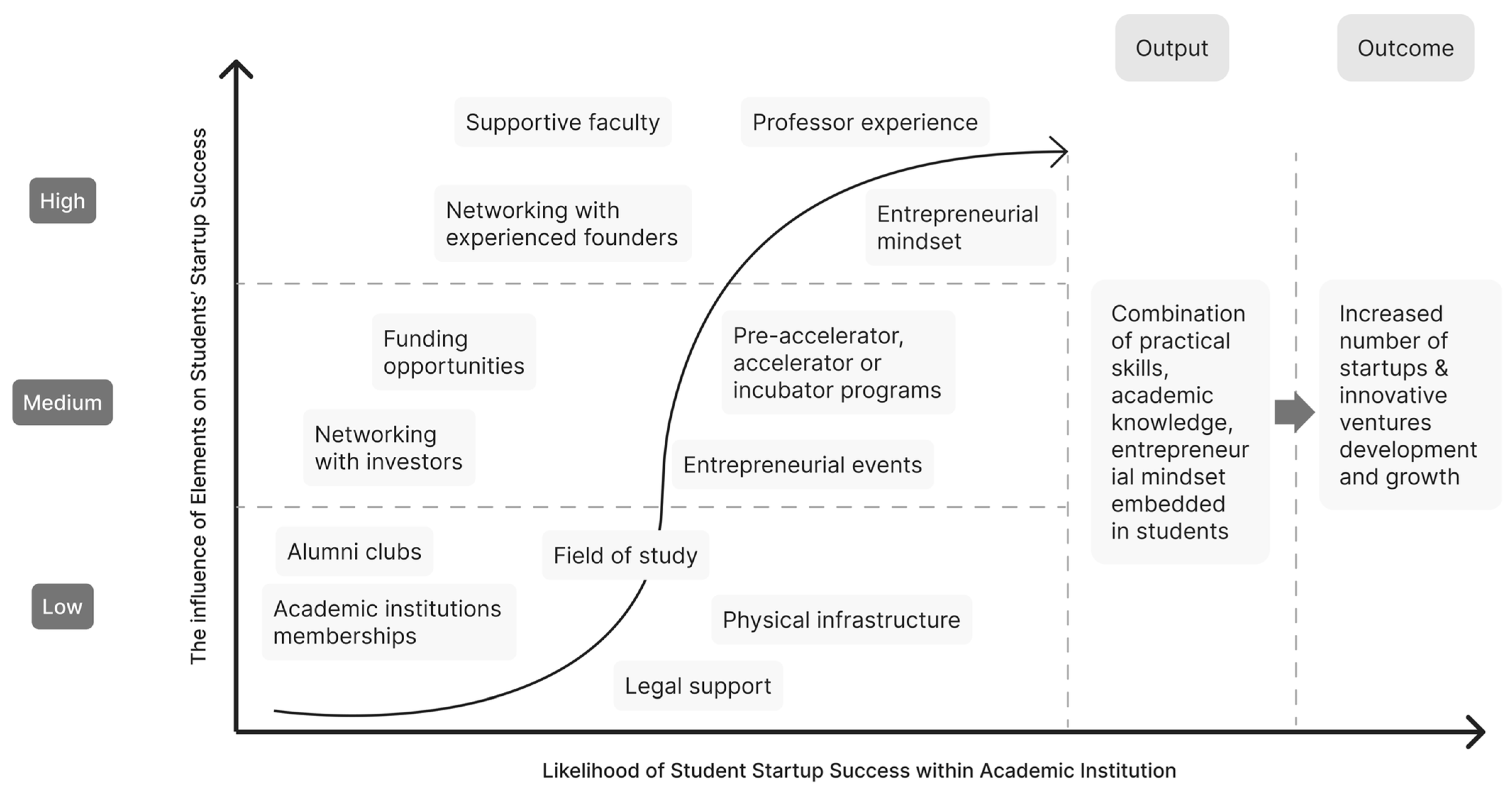

5. Discussion

5.1. High-Impact Factors

5.2. Medium-Impact Factors

5.3. Low-Impact Factors

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations

6.4. Agenda for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Factor Group | No. | Statement |

|---|---|---|

| Educational programs (curriculum & courses) | 1 | Bachelor’s programs in start-ups and entrepreneurship can foster start-ups development at higher educational institutions |

| 2 | A higher number of technological subjects taught at educational institutions can foster the creation of start-ups | |

| 3 | A higher number of entrepreneurship subjects taught at educational institutions can foster the creation of start-ups | |

| 4 | The field of study is perceived to influence start-up success, with non-business students considered to be at a relative disadvantage compared to those in business-related disciplines | |

| 5 | Access to the latest technologies on campus can significantly enhance the potential for start-up success | |

| 6 | Professors with prior entrepreneurial or business experience are seen as key enablers of successful student start-up development | |

| 7 | The entrepreneurial atmosphere and culture of an institution, play a crucial role in fostering a conducive environment for start-up development and success | |

| 8 | Supportive academic staff guide students’ entrepreneurial efforts by embedding mentorship, resources, and encouragement within the learning process, helping transform ideas into viable start-up initiatives | |

| 9 | Involvement of university in scientific research on start-up, innovation, and entrepreneurial endeavors enhance the successful start-up development | |

| University entrepreneurial incentives (informal) | 10 | Participation in structured pre-accelerator initiatives can effectively stimulate student engagement in early-stage venture development |

| 11 | Accelerator programs tailored to student’ needs can play a key role in advancing their entrepreneurial initiatives | |

| 12 | Student access to incubator services can support the transition of start-up ideas into actionable business models through guided development | |

| 13 | The active programs of a start-up studio can significantly foster students’ initiatives in developing start-ups | |

| Events and Networking | 14 | Hackathons, framed as entrepreneurial competitions, can foster the creation of student-run startups |

| 15 | Academic and practical entrepreneurship conferences at higher educational institutions can foster the creation of student-run startups | |

| 16 | Workshops at higher educational institutions can foster the creation of student-run start-ups | |

| 17 | Summer start-up bootcamps organized by higher educational institutions can be catalysts for students to create their startups | |

| 18 | Connecting with experienced entrepreneurs through networking opportunities can enhance the development of student-led start-ups | |

| 19 | Connecting with potential investors through targeted networking can support the growth and viability of student-initiated ventures | |

| 20 | Networking with entrepreneurial alumni can encourage student-run start-up development | |

| 21 | HEI memberships in diverse networks, such as business angels’ associations, can provide valuable resources and connections, further facilitating the growth of student-run start-up ventures | |

| HEI’s direct support | 22 | Access to legal and regulatory support, such as trademarking, patenting, and business registration, can support the creation and growth of student ventures within HEIs |

| 23 | Allocating dedicated spaces and facilities (e.g., labs, innovation corners, coworking hubs) can meaningfully contribute to students’ start-up activities and development efforts | |

| Student-run incentives, internal motivation & attitudes | 24 | Entrepreneurial and student-led start-up clubs contribute to an innovation-oriented environment by facilitating peer support, collaboration, and shared learning, which can enhance start-up success |

| 25 | Events organized by students create dynamic platforms for networking, skill-building, and idea exchange, serving as catalysts for nurturing and propelling student-led start-ups | |

| 26 | Embracing risk tolerance, fueled by ambition and a readiness to tackle challenges, is fundamental for budding entrepreneurs, as these traits often dictate the trajectory and resilience of their start-up journeys | |

| 27 | Actively embracing challenges outside one’s academic comfort zone can serve as a driving force in advancing student-led entrepreneurial initiatives | |

| 28 | Viewing failure as a learning opportunity and maintaining a growth-oriented mindset are essential elements in the development of student-driven start-ups | |

| 29 | Confidence in one’s abilities strengthens perseverance and plays a fundamental role in achieving success in student-run start-ups | |

| 30 | Thrive for industry experience is one of the key factors for successful student-run startup development | |

| 31 | Growing up in an entrepreneurial family or having parents engaged in business ventures can significantly increase the likelihood of a student launching a successful startup | |

| Funding opportunities | 32 | Direct investment by HEIs in student-run start-ups can catalyze and encourage the emergence of more such entrepreneurial ventures |

| 33 | Private investments from sources such as internal funds, private investors, sponsors, and corporates can catalyze and encourage the emergence of more student-run entrepreneurial ventures | |

| 34 | Project-based funding, whether from national or EU projects, as well as grants, can catalyze and encourage the emergence of more student-run entrepreneurial ventures |

References

- Ahn, S., Kim, K.-S., & Lee, K.-H. (2022). Technological capabilities, entrepreneurship and innovation of technology-based start-ups: The resource-based view. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(3), 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanasreh, E., Moles, R., & Chen, T. F. (2019). Evaluation of methods used for estimating content validity. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 15(2), 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aryadita, H., Sukoco, B. M., & Lyver, M. (2023). Founders and the success of start-ups: An integrative review. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3), 2284451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangdiwala, M., Mehta, Y., Agrawal, S., & Ghane, S. (2022, October 1–6). Predicting success rate of startups using machine learning algorithms. 2022 2nd Asian Conference on Innovation in Technology (ASIANCON), Ravet, India. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bist, A. S. (2023). The importance of building a digital business startup in college. Startupreneur Business Digital (SABDA Journal), 2(1), 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldureanu, G., Ionescu, A. M., Bercu, A.-M., Bedrule-Grigoruță, M. V., & Boldureanu, D. (2020). Entrepreneurship education through successful entrepreneurial models in higher education institutions. Sustainability, 12(3), 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, H., & Boone, D. (2012). Analyzing likert data. Journal of Extension, 50(2), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breznitz, S. M., & Zhang, Q. (2019). Fostering the growth of student start-ups from university accelerators: An entrepreneurial ecosystem perspective. Industrial and Corporate Change, 28(4), 855–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantamessa, M., Gatteschi, V., Perboli, G., & Rosano, M. (2018). Startups’ roads to failure. Sustainability, 10(7), 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockayne, D. (2019). What is a startup firm? A methodological and epistemological investigation into research objects in economic geography. Geoforum, 107, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, M. P., Marques, C. S., Silva, R., & Ramadani, V. (2024). Academic entrepreneurship ecosystems: Systematic literature review and future research directions. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 15(4), 17498–17528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Santamaría, C., & Bulchand-Gidumal, J. (2021). Econometric estimation of the factors that influence startup success. Sustainability, 13(4), 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Awad, Z., Gabrielsson, J., Pocek, J., & Politis, D. (2024). Unpacking the early alumni engagement of entrepreneurship graduates. Journal of Small Business Management, 62(3), 1219–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, M., & Aamoucke, R. (2017). Fields of knowledge in higher education institutions, and innovative start-ups: An empirical investigation. Papers in Regional Science, 96, S1–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, N., Murti, A. B., & Dwivedi, R. (2023). Why do Indian startups fail? A narrative analysis of key business stakeholders. Indian Growth and Development Review, 16(2), 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramm, K. M., Doerfert, D. L., Boren-Alpízar, A. E., Burris, S., & Ritz, R. (2024). Enabling university and regional conditions to create a thriving entrepreneurship ecosystem. Journal of the International Council for Small Business, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M., & Urbano, D. (2012). The development of an entrepreneurial university. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 37(1), 43–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M., Urbano, D., Cunningham, J. A., & Gajón, E. (2018). Determinants of graduates’ start-ups creation across a multi-campus entrepreneurial university: The case of monterrey institute of technology and higher education. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(1), 150–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, D., Minola, T., Van Gils, A., & Huybrechts, J. (2017). Entrepreneurial education and learning at universities: Exploring multilevel contingencies. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 29(9–10), 945–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneberg, D. H., & Aaboen, L. (2020). Incubation of technology-based student ventures: The importance of networking and team recruitment. Technology in Society, 63, 101402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg, G., & Kurczewska, A. (2021). Toward a learning philosophy based on experience in entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 4(1), 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirapong, K., Cagarman, K., & von Arnim, L. (2021). Road to sustainability: University–start-up collaboration. Sustainability, 13(11), 6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakouris, A., & Liargovas, P. (2021). On the about/for/through framework of entrepreneurship education: A critical analysis. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 4(3), 396–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakouris, A., Tampouri, S., Kaliris, A., Mastrokoukou, S., & Georgopoulos, N. (2023). Entrepreneurship as a career option within education: A critical review of psychological constructs. Education Sciences, 14(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassim, N. M., Alshukaili, A., Zain, M., Ravi, A., Muneerali, M., & Sharif, K. (2024). Effects of entrepreneurship education components on entrepreneurial intentions in Oman. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, D. M. H., & Rahman, N. A. (2020). How to measure start-up success? A systematic review from a multidimensional perspective. SSRN Electronic Journal, 2010, 3638863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, D. M. H., Yusoff, Y. M., & Khin, S. (2019). The role of support on start-up success: A PLS-SEM approach. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 24(Suppl. S1), 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, C., & Etemad, H. (2011). The impact of entrepreneurial capital and rapidly growing firms: The Canadian example. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 12(3), 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsios, F., Sitaridis, I., & Kamariotou, M. (2021). Entrepreneurial education and emotional intelligence: A state of the art review. Contemporary Issues in Entrepreneurship Research, 11, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyver, K., & Schenkel, M. T. (2013). From resource access to use: Exploring the impact of resource combinations on nascent entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(4), 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusmaryono, I., Wijayanti, D., & Maharani, H. R. (2022). Number of response options, reliability, validity, and potential bias in the use of the likert scale education and social science research: A literature review. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 8(4), 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landoni, M., Bolzani, D., & Baroncelli, A. (2021). The role of alumni clubs in the universities’ entrepreneurial networks: An inquiry in Italian universities. In Universities and entrepreneurship: Meeting the educational and social challenges (Vol. 11, pp. 49–63). Contemporary Issues in Entrepreneurship Research. Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, R., & Blashfield, R. K. (1978). Performance of a composite as a function of the number of judges. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 21(2), 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, A., & Theodoraki, C. (2021). Achieving interorganizational ambidexterity through a nested entrepreneurial ecosystem. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 68(2), 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyken-Segosebe, D., Mogotsi, T., Kenewang, S., & Montshiwa, B. (2020). Stimulating academic entrepreneurship through technology business incubation: Lessons for the incoming sponsoring university. International Journal of Higher Education, 9(5), 17970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malecki, E. J. (2018). Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Geography Compass, 12(3), e12359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliou, O., & Ioannou, A. (2024). Evaluation of the impact of a university accelerator on students’ entrepreneurial attitudes, intentions, and learning experience. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M. H., Shirokova, G., & Tsukanova, T. (2017). Student entrepreneurship and the university ecosystem: A multi-country empirical exploration. European Journal of International Management, 11(1), 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, C. E. (2023). Startup grants and the development of academic startup projects during funding: Quasi-experimental evidence from the German ‘EXIST—Business startup grant’. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 20, e00408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumu, J., Tanujaya, B., Charitas, R., & Prahmana, I. (2022). Likert scale in social sciences research: Problems and difficulties. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 16(4), 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G., Liñán, F., Fayolle, A., Krueger, N., & Walmsley, A. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: A systematic review and research agenda. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 16(2), 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/European Union. (2018). Supporting entrepreneurship and innovation in higher education in The Netherlands. In OECD skills studies. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paray, Z. A., & Kumar, S. (2020). Does entrepreneurship education influence entrepreneurial intention among students in HEI’s? Journal of International Education in Business, 13(1), 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathania, A., & Tanwar, S. (2024). Decoding startup failures in Indian startups: Insights from interpretive structural modeling and cross-impact matrix multiplication applied to classification. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 20(2), 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D. F., Beck, C. T., & Owen, S. V. (2007). Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health, 30(4), 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M. F., Leitão, J., & Cantner, U. (2022). Measuring the efficiency of an entrepreneurial ecosystem at municipality level: Does institutional transparency play a moderating role? Eurasian Business Review, 12(1), 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A. L., Cerdeira, L., Machado-Taylor, M. d. L., & Alves, H. (2021). Technological skills in higher education—Different needs and different uses. Education Sciences, 11(7), 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roebianto, A., Savitri, S. I., Aulia, I., Suciyana, A., & Mubarokah, L. (2023). Content validity: Definition and procedure of content validation in psychological research. TPM—Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 30(1), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Martín, P., Fernández-Laviada, A., Pérez, A., & Palazuelos, E. (2021). The teacher of entrepreneurship as a role model: Students’ and teachers’ perceptions. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, R. T. P. B., Junaedi, I. W. R., Priyanto, S. H., & Santoso, D. S. S. (2021). Creating a startup at a University by using Shane’s theory and the entrepreneural learning model: A narrative method. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla-Bernardo, J., Sanchez-Robles, B., & Herrador-Alcaide, T. C. (2022). Success factors of startups in research literature within the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Administrative Sciences, 12(3), 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirokova, G., Tsukanova, T., & Morris, M. H. (2018). The moderating role of national culture in the relationship between university entrepreneurship offerings and student start-up activity: An embeddedness perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(1), 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, N. A., Khaliq, M. A., Pirzada, M. A., Rehman, Z., Shaikh, F., Riaz, A., & Khan, S. (2024). Development and content validation of a financial and functional outcomes tool for diabetes-related foot disease in patients undergoing major lower limb amputation: A prospective observational study from Pakistan. BMJ Open, 14(3), e080853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N., Ponde, V., Jagannathan, B., Rao, P. B., Dixit, A., & Agarwal, G. (2021). Development and validation of a questionnaire to study practices and diversities in Plexus and Peripheral nerve blocks. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, 65(3), 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, O. P., Vaughan, B., Sampath, K., Draper-Rodi, J., Fleischmann, M., & Cerritelli, F. (2022). The Osteopaths’ Therapeutic Approaches Questionnaire (Osteo-TAQ)—A content validity study. International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine, 45, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelderen, M. (2023). Using a comfort zone model and daily life situations to develop entrepreneurial competencies and an entrepreneurial mindset. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1136707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardhan, J., & Mahato, M. (2022). Business incubation centres in universities and their role in developing entrepreneurial ecosystem. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Emerging Economies, 8(1), 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S. M., Rau, C., & Lindemann, E. (2010). Multiple informant methodology: A critical review and recommendations. Sociological Methods & Research, 38(4), 582–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Sun, X., Liu, S., & Mu, C. (2021). A preliminary exploration of factors affecting a university entrepreneurship ecosystem. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 732388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wraae, B., Brush, C., & Nikou, S. (2022). The Entrepreneurship Educator: Understanding Role Identity. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 5(1), 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M., Siegel, D. S., & Mustar, P. (2017). An emerging ecosystem for student start-ups. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 42(4), 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: design and methods (5th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Zichella, G., & Reichstein, T. (2023). Students of entrepreneurship: Sorting, risk behaviour and implications for entrepreneurship programmes. Management Learning, 54(5), 727–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Success Factors | Description | Author(s), Date |

|---|---|---|

| Formal educational programs | Business and entrepreneurship curricula improve students’ conceptual and operational understanding of start-up development | (Breznitz & Zhang, 2019; Hahn et al., 2017; Kassim et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2021; Zichella & Reichstein, 2023) |

| Technological skills | Integrating digital competencies into entrepreneurship education enhances students’ ability to innovate and leverage technology | (Ahn et al., 2022; Haneberg & Aaboen, 2020; Rodrigues et al., 2021) |

| Entrepreneurial mindset and personal traits | Psychological traits such as risk tolerance, openness to failure, and motivation shape entrepreneurial intention | (Hägg & Kurczewska, 2021; Kitsios et al., 2021; Van Gelderen, 2023; Zichella & Reichstein, 2023) |

| Supporting mechanism | Access to pre-accelerators, incubators, and accelerators provides experiential learning, mentoring, and networks | (Lo & Theodoraki, 2021; Lyken-Segosebe et al., 2020; Miliou & Ioannou, 2024; Morris et al., 2017; Vardhan & Mahato, 2022) |

| Alumni | Alumni clubs and mentorship structures can offer early-stage support and industry-specific insights | (El-Awad et al., 2024; Landoni et al., 2021; Wraae et al., 2022; Wright et al., 2017) |

| The professor’s previous experience in business | Professors with entrepreneurial backgrounds can influence students’ intention and confidence through role modeling | (Boldureanu et al., 2020; San-Martín et al., 2021; Wraae et al., 2022) |

| Funding | Access to HEIs or external seed funding significantly enhances students’ ability to test and scale business ideas | (Klyver & Schenkel, 2013; Morris et al., 2017; Mueller, 2023; Shirokova et al., 2018) |

| No. of Statement | Statement | Mean Score |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | Professors with prior entrepreneurial or business experience are seen as key enablers of successful student start-up development | 2.67 |

| 18 | Connecting with experienced entrepreneurs through networking opportunities can enhance the development of student-led start-ups | 2.65 |

| 29 | Confidence in one’s abilities strengthens perseverance and plays a fundamental role in achieving success in student-run start-ups | 2.64 |

| 28 | Viewing failure as a learning opportunity and maintaining a growth-oriented mindset are essential elements in the development of student-driven start-ups | 2.61 |

| 8 | Supportive academic staff guide students’ entrepreneurial efforts by embedding mentorship, resources, and encouragement within the learning process, helping transform ideas into viable start-up initiatives | 2.56 |

| No. of Statement | Statement | Mean Score |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | The field of study is perceived to influence start-up success, with non-business students considered to be at a relative disadvantage compared to those in business-related disciplines | 1.64 |

| 32 | Direct investment by HEIs in student-run start-ups can catalyze and encourage the emergence of more such entrepreneurial ventures. | 2.20 |

| 22 | Access to legal and regulatory support, such as trademarking, patenting, and business registration, can support the creation and growth of student ventures within HEIs | 2.28 |

| 34 | Project-based funding, whether from national or EU projects, as well as grants, can catalyze and encourage the emergence of more student-run entrepreneurial ventures | 2.30 |

| 21 | HEI memberships in diverse networks, such as business angels’ associations, can provide valuable resources and connections, further facilitating the growth of student-run start-up ventures. | 2.32 |

| No. of Statement | Statement | Mean Score |

|---|---|---|

| 16 | Workshops at higher educational institutions can foster the creation of student-run start-ups | 2.10 |

| 6 | Professors with prior entrepreneurial or business experience are seen as key enablers of successful student start-up development | 2.12 |

| 8 | Supportive academic staff guide students’ entrepreneurial efforts by embedding mentorship, resources, and encouragement within the learning process, helping transform ideas into viable start-up initiatives | 2.18 |

| 11 | Accelerator programs tailored to student needs can play a key role in advancing their entrepreneurial initiatives | 2.20 |

| 5 | Access to the latest technologies on campus can significantly enhance the potential for start-up success | 2.21 |

| No. of Statement | Statement | Mean Score |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | The field of study is perceived to influence start-up success, with non-business students considered to be at a relative disadvantage compared to those in business-related disciplines | 3.69 |

| 23 | Allocating dedicated spaces and facilities (e.g., labs, innovation corners, coworking hubs) can meaningfully contribute to students’ start-up activities and development efforts | 3.36 |

| 26 | Embracing risk tolerance, fueled by ambition and a readiness to tackle challenges, is fundamental for budding entrepreneurs, as these traits often dictate the trajectory and resilience of their start-up journeys | 3.14 |

| 27 | Actively embracing challenges outside one’s academic comfort zone can serve as a driving force in advancing student-led entrepreneurial initiatives | 3.12 |

| 20 | Networking with entrepreneurial alumni can encourage student-run start-up development | 3.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jurgelevičius, A.; Butvilas, T.; Kovaitė, K.; Šūmakaris, P. Developing an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Framework for Student-Led Start-Ups in Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070837

Jurgelevičius A, Butvilas T, Kovaitė K, Šūmakaris P. Developing an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Framework for Student-Led Start-Ups in Higher Education. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):837. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070837

Chicago/Turabian StyleJurgelevičius, Artūras, Tomas Butvilas, Kristina Kovaitė, and Paulius Šūmakaris. 2025. "Developing an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Framework for Student-Led Start-Ups in Higher Education" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070837

APA StyleJurgelevičius, A., Butvilas, T., Kovaitė, K., & Šūmakaris, P. (2025). Developing an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Framework for Student-Led Start-Ups in Higher Education. Education Sciences, 15(7), 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070837