Quality early childhood education helps children succeed in life. Children’s social, emotional, and learning outcomes are enhanced with high-quality experiences and educator–child interactions (

Eadie et al., 2022;

Howard et al., 2018;

Phillips & Shonkoff, 2000). ECE plays a crucial role in bridging the gap in outcomes between advantaged and disadvantaged children, a gap that starts long before children enter school (

O’Connell et al., 2016). The importance of improving quality in ECE has gained visibility in Australian early childhood education policy agendas over the last decade. The

National Early Childhood Development Strategy (

Commonwealth of Australia, 2009) was an initial response demonstrating the government’s policy focus on quality. The concept of quality became part of a contemporary ECE rhetoric, policy and practice, fueled further by the implementation of the

National Quality Standard (NQS) (

Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority [ACECQA], 2018) and the related national guideline, the

Early Years Learning Framework V2 (EYLF) (

AGDE, 2022), that underpins learning in the years prior to schooling. Raising and sustaining high-quality ECE has become a key focus area for key stakeholders, governments, and educators. This article argues that children’s voices should be included in defining quality early childhood education and highlights their unique perspectives as the main beneficiaries.

1.1. Why Is Quality Important in ECE?

Quality experiences in ECE services positively impact children’s development. Early education helps children develop skills linked to better cognitive, communication, and social-emotional development (

Cloney et al., 2015;

Krieg et al., 2015;

Torii et al., 2017). Quality early education reduces developmental gaps and improves educational opportunities (

Cloney et al., 2015).

Early childhood interventions lead to better long-term results, such as higher education levels, better economic and social participation, less involvement in crime, and improved family wellbeing (

Manning et al., 2019;

Schweinhart et al., 2005). For example, drawing on neuroscience, the

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (

OECD, 2022,

2024) highlights the critical development that occurs in the early years. When the overall quality and effectiveness of ECE is increased, improvements in children’s long-term outcomes result, providing economic benefits (

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD], 2022). The positive effects on children’s development and outcomes were particularly impactful for those children facing vulnerabilities of disadvantage (

Gialamas et al., 2014,

2015). In short, early investment yields long-term gains. Despite the evidence clearly showing the importance of high-quality experiences for children in the early years, too many children are missing out, particularly at-risk children who face disadvantage (

Torii et al., 2017). Children who attend services rated as ‘exceeding’ the national quality standard (or above) had consistently lower rates of developmental vulnerability than children in services rated ‘working towards’ the national quality standard or ‘significant improvement’ required (

Rankin et al., 2024). Low-quality childcare significantly hinders the language and cognitive development of children living in disadvantaged conditions (

Melhuish et al., 2016). Since high-quality early childhood education is crucial for children’s development, it is important to include everyone’s views on quality to make sure all children, especially those facing disadvantage, experience quality ECE.

1.2. What Is Quality in ECE? A Contested Space Dominated by Adult Stakeholders

While it is agreed that quality ECE is critical, no universal definition of quality exists. What counts as quality in early education has been re-contextualized, reconstructed, and is constantly under review (

Eadie et al., 2022). The characteristics of what determines quality differ, and there are discrepancies between policy intentions and actual practices (

Penn, 2011). The concept of quality in ECE is fluid and contested, shaped by shifting contexts, varied perspectives, and gaps between policy and practice.

Quality in ECE has been broadly categorized into structural and process quality (

Dowsett et al., 2008;

Mashburn, 2008;

Vandell & Wolfe, 2000). More recently, a third domain of quality focuses on systems. System quality encompasses factors such as governance, regulatory benchmarks, and the extent of investment in services and programs (

Eadie et al., 2022;

Torii et al., 2017). The Infant–Toddler Environment Rating Scale-Revised (ITERS-R) and the Early Childhood Environment Rating Scale-Revised (ECERS-R) (

Harms et al., 1998,

2003) have provided a comprehensive appraisal of structural and process aspects, including activities, interactions, and physical settings. Structural aspects of quality are easily measurable, including ratios, qualifications, and group size, and they have been a feature of much of the research into quality (

Whitebook et al., 1989). That children have been largely excluded from the debate about quality may be due to an emphasis on structural quality.

Process quality refers to relationships, interactions, and engagement (

Eadie et al., 2022). Process factors rely on educator skills and practices, and these are crucial to the quality of the learning environment and children’s outcomes (

Ha et al., 2024;

Sheridan & Pramling Samuelsson, 2009). High-quality programs are inclusive and responsive in their delivery of curricula, planning, pedagogies, and assessment strategies, and, in turn, foster access and engagement in ECE (

Cohrssen et al., 2023). Quality relationships in formal ECE are crucial in narrowing developmental gaps. The impact of higher quality childcare through strong relationships with caregivers on children’s cognitive and behavioral development at school entry is more significant for children living in disadvantage (

Gialamas et al., 2014,

2015). Inclusive and responsive learning environments are especially beneficial for fostering children’s development.

Eadie et al.’s (

2022) systematic review on quality in ECE found that most research spotlights structural quality, including professional development and support. Although structural elements remain important, attention has turned to children’s interactional experiences with peers, educators, and resources as key elements of process quality (

Eadie et al., 2022;

Ha et al., 2024). Using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS),

Melhuish et al. (

2016) found that when children are involved in extended conversations, they have greater gains across developmental domains. For example, teachers who engage in sustained shared thinking with children enhance their wellbeing (

Howard et al., 2018). To better understand the quality of early childhood education, it is important to gather insights directly from the children themselves.

The strengths and limitations of current measures of quality have long been under debate. Typically, it is adult stakeholders who are consulted regarding what is quality and quality assurance regulation. A study by the

Australian Community Children’s Services (

2021) highlighted key factors contributing to quality ECE. These included better-qualified educators, competitive wages, increased professional development, and improved staff retention.

Harrison et al.’s (

2019) mixed-methods study on quality improvement investigated internal methods of quality improvement within educational programs and practice, and governance and leadership aspects of ECE in Australia. The study found that meaningful engagement with national assessment and rating procedures was useful for achieving continuous quality improvement.

Brownlee et al. (

2009) investigated the beliefs and actions of ECE educators and directors using semi-structured interviews and observations of interactions (

Brownlee et al., 2009). They identified that the educators and directors focused on the importance of individualization of care and programming for development, while the directors also identified parent interactions and programming for learning as important factors of quality. These studies provide useful insights into how regulations affect quality and the important role authorities have in ensuring compliance and improving quality.

Ishimine et al. (

2010) emphasized the need for improved methods to assess ECE quality, advocating for evaluations that go beyond merely meeting basic standards. Engaging stakeholders in conversations is essential to reach a consensus on the characteristics of quality (

Cohrssen et al., 2023). When ECE educators, primary caregivers, regulators, researchers, and policymakers collaborate, accountability for quality is shared across the sector (

Cohrssen et al., 2023). While children are a central focus of planning; however, their views are not typically considered in proposed future frameworks, which leads to an incomplete picture.

1.3. Increasing Quality ECE

Increasing quality is linked to ensuring quality teaching and learning, and improving access for children. Quality ECE factors include effective recruitment (

Valentine & Thomson, 2009), comprehensive teacher training and qualifications (

Manning et al., 2019), teacher wellbeing and feeling supported (

Cumming et al., 2021), and ongoing professional development (

Hansen & Ringsmose, 2023;

Melhuish et al., 2016). Qualified educators influence the quality of early education. A meta-analytic review by

Manning et al. (

2019) examined the correlation between teacher qualifications and the quality of ECE environments. Results showed that higher teacher qualifications are significantly correlated with higher quality ECE environments and program structure, specifically children’s language and reasoning.

ECE workforce shortages are highlighted nationally and internationally, and this further impacts the quality of ECE provision. For example,

Fenech et al. (

2021) investigated the recruitment, retention, and wellbeing of early childhood teachers in Australia. They found that a well-qualified, well-paid, stable workforce with high psychological and emotional wellbeing is critical to the provision of quality early childhood education and care. These findings highlight the need for further research, particularly large-scale longitudinal studies, to investigate factors influencing the attraction, retention, and sustainability of early childhood teachers and how these factors impact teacher quality.

1.4. Incorporating Children’s Perspectives on Quality ECE

The diverse factors influencing ECE quality accentuate the importance of considering the perspectives and contexts of all stakeholders. As the main users of early childhood education, children’s voices must be heard in a space dominated by adult stakeholders. Most studies focused on quality seek educator or parent views on children’s participation. For example,

Gialamas et al. (

2014,

2015) investigated whether higher quality childcare was linked to better developmental outcomes at school entry, particularly for children from lower-income families compared to those from higher-income families. The study used data from the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (

Sanson et al., 2002), focusing on children aged 2–3 years who attended ECE (sample size ranged from 980 to 1187). The impact of higher-quality ECE, particularly through strong relationships with caregivers, on children’s cognitive and behavioral development at school entry was more significant for children from lower-income families. When educators combine explicit teaching of skills and concepts with sensitive and warm, play-based interactions, they have the most impact (

Torii et al., 2017). However, there has been little investigation of what counts as quality from a child’s perspective.

Children’s voices are increasingly being emphasized in early childhood research and policy, driven by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) (

United Nations, 1989). Although children are the primary beneficiaries of ECE, there are questions about whether they can be reliable participants in research studies. Quality may not be a term that children are familiar with. When appropriate child-friendly methods are used; however, children’s input can be meaningful (

Danby et al., 2011;

Eder & Fingerson, 2003;

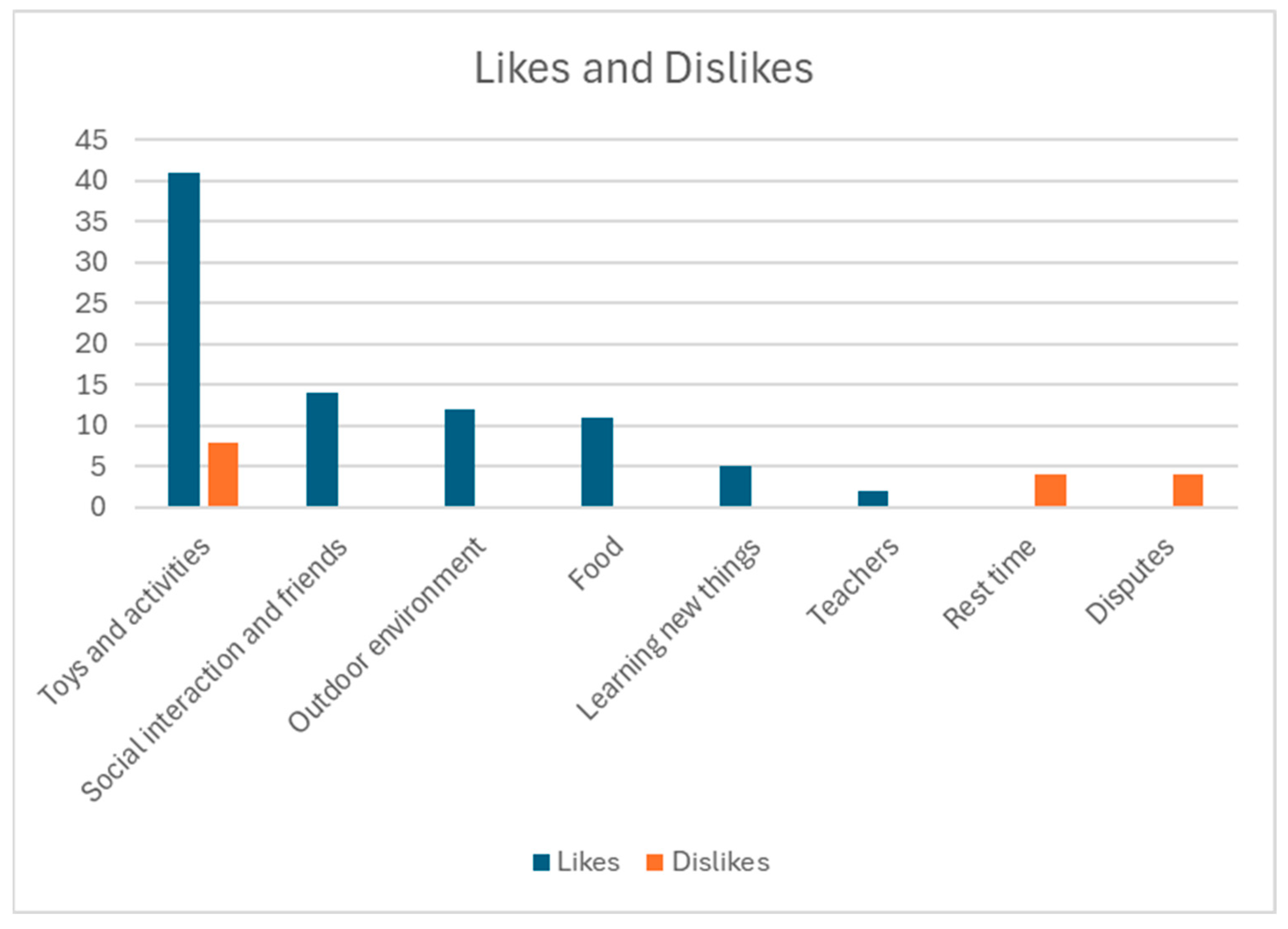

Einarsdóttir, 2014). This article brings children’s voices to the forefront by capturing their thoughts on what they love and dislike about preschool, and their vision of what makes a ‘good’ preschool. The findings present the perspective of a key stakeholder previously overlooked in debates over what constitutes quality in ECE.