Abstract

Communication between families and schools is foundational for students’ academic success, community support for schools, and teachers’ experience. Yet, few preservice teacher education programs teach novices how to engage in equitable and effective collaborations with families. This manuscript reports on a pilot study in which preservice teachers traveled to a local community school and role-played academic conversations with adults whose children were enrolled in the school. The analysis of the transcripts of the role plays, a debrief panel by family participants, and written reflections of eight participating preservice teachers and six family participants used codes derived from the Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships. The findings show that both groups of participants found opportunities for thoughtful engagement. In the role plays, preservice teachers were most likely to demonstrate cognition by thinking flexibly about how to accommodate family and student needs. Family participants were most likely to demonstrate confidence by displaying their expertise and coaching the teachers. Activities like this may be useful sites for teachers and community members to practice effective collaboration skills. More broadly, the results may point toward an underutilized capacity within preservice teacher education to support family- and community-oriented schooling.

1. Introduction

A growing body of literature is making the case that equitable collaboration between families and schools can have a positive influence on a wide array of educational outcomes, including academic achievement, classroom dynamics, school behavior, student–teacher relationships, and cultural competence (Smith et al., 2022). This research reflects the understanding that teachers and schools are not solely responsible for learning outcomes because school systems are deeply enmeshed within a child’s first family system—where they develop secure attachments, establish routines, and experience foundational growth (Quezada et al., 2013; Ruberry et al., 2018; Sheridan et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2022). And, that relationship is not unidirectional. When parents are engaged in their child’s school, they are more confident in their parenting skills, their capacity to support their children to learn at home, and their ability to communicate with teachers (Reinke et al., 2019; Epstein et al., 2018). If equitable collaboration between schools and families can foster a mutually beneficial reciprocal relationship between parental, student, and school well-being, then developing the capacity of all parties to engage in such dialogue is a critical investment in school and community success.

1.1. Challenges to Teacher–Family Communication

Despite the common expectation that teachers are strong communicators, interaction between teachers and parents is often fraught (De Coninck et al., 2018). Limited time, insufficient structural support from schools, and the widespread perception that parents are part of the problem all make it difficult for teachers to engage families as partners with a shared investment in students’ well-being and learning (Azad et al., 2018; Symeou et al., 2012). For their part, teachers routinely express frustration that parents are not more engaged in their child’s schooling, and parents say they are not welcome in the school and are made to feel they are meddling when they contact teachers (Froiland, 2020; Gonzalez-DeHass & Willems, 2003). Moreover, problems with family communication appear to emerge early, even before teachers enter the field. Preservice teachers often evince uncertainty about fostering partnerships with parents due to their limited experience, and, even after completing coursework about family engagement, lack confidence in their ability to communicate well with parents (Alaçam & Olgan, 2019; Meehan & Meehan, 2017; Nathans et al., 2020). Compounding these problems of practice are two key issues: unclear definitions of family–school engagement and insufficient training for preservice teachers on how to engage with families.

1.2. Understanding Family–School Engagement

Despite broad agreement that family–school engagement is important, there is little consensus as to what family–school engagement means. Terms describing interactions between schools and families are often used interchangeably and can be specific to a particular practice or research area (see Smith et al., 2019). Epstein (2018), for example, cataloged six kinds of interactions between school and community that include communication, volunteering, decision-making, and collaborating, all of which might be considered family–school engagement. The proliferation of inconsistent terminology to describe the relationships between community and school can mask real differences in application and opportunity. Increasingly, scholars are distinguishing between mere family (or parent) involvement, a goal that places parents in a passive role that upholds existing school culture and sidesteps addressing uneven power dynamics, and family engagement, a goal to empower parents as active citizens and change agents capable of transforming schools and neighborhoods (Ishimaru, 2019; Shirley, 1997).

The recognition that engagement is preferable to involvement has prompted renewed efforts to shift the norms of schooling toward more equitable and collaborative relationships between families and schools. Pushor’s (2015) familycentric schooling approach, for example, expands the role of family–school engagement even further, centering families in both the curriculum and pedagogy, and teachers “walk alongside them” (p. 199). Familycentric schools are designed for and with families, as opposed to the common schoolcentric approach where the school is the central node of learning, and the family voice and contribution to their child’s education is minimized (Pushor, 2017).

1.3. Family-Centric Schooling in Community Schools

An iteration of family-centric schooling is the community schools strategy, where teachers, families, school staff, and community members and organizations form partnerships and work collaboratively to address educational inequities and community-identified problems (Daniel et al., 2019). Built on the premise that schools can and should function as core neighborhood centers that serve and educate youth, community schools aim to democratically engage families and local community members and incorporate community and family funds of knowledge into classroom planning and school decision-making (Daniel et al., 2019; Harkavy et al., 2016; Heers et al., 2016). Notably, while community schools do place the school at the center of student learning and development, the approach is distinguished from the school-centric approach in that the school is viewed as a resource and physical location—akin to a community center. Schools are often centrally located and convenient for bringing together parents, educators, and community members. Furthermore, community schools are places where families, students, and educators can build linking social capital, where bonds are built across differences in resources and status and new types of relationships emerge that bridge distinct systems of power, effectively sharing the responsibility of educating students across schools, families, and communities (Rimkunas & Mellin, 2023; Mayger & Hochbein, 2021). In affirming the school, and usually the traditional public school, as the linchpin of the relationship between teachers, families, and students, the community schools model marks itself as somewhat less radical than other critical reimaginings of education like abolitionist teaching (Love, 2019) or forms of grassroots parental activism that have challenged the primacy of schools within education (Fennimore, 2017). Working from the perspective that there are affordances to working within existing institutional structures, this study was intentionally conducted in a school district that implements community schools in partnership with the local university. The community schools model is one pathway to creating a family-centric schooling context—both in the understanding and the practice of family–school engagement. Integrating teacher preparation within this context may provide insight for the broader project of reorienting education around family and community needs.

1.4. Capacity-Building for Family–School Engagement

Making schooling more family-centric will require both parents and educators to learn to engage in more meaningful family–school partnerships (Mapp & Kuttner, 2013). Teacher training programs, however, have not met the demand for training in family engagement skills. A recent national report on teacher education for family collaboration, for example, indicated that preservice programs rarely support new teachers in family communication and cited an overcrowded curriculum, a lack of community investment in teacher preparation in this domain, and few state imperatives to engage in family collaboration work as amongst the barriers to better preparation (National Association for Family, School, and Community Engagement, 2022). Still, there are indications that preservice teachers who engage in family engagement activities during their training are more likely to implement active family engagement strategies (Uludag, 2008) and develop positive perceptions of teacher–parent communication (Jacobbe et al., 2012; Taylor & Kim, 2019). The need in community schools, in particular, and teaching more generally, for educators who are prepared to collaborate with families should spur teacher education programs to consider new pedagogies for supporting community-oriented early career teachers.

1.5. Practice-Based Teacher Education

Practice-based teacher education provides a potential framework for preparing teachers to engage in more productive collaboration with families. Practice-based teacher education scholarship argues that having teachers engage with enacted instructional practices in ways that motivate deeper enmeshment with theory can bridge the theory–practice divide (Grossman, 2018; McDonald et al., 2013). This model requires identifying core practices with enough complexity and conceptual heft to support meaningful decomposition (Kavanagh et al., 2025). Without a rich site of practice and investigation, teacher educators may convey the impression that teaching is a technocratic exercise, a misperception that animates inequitable teacher education and teaching (Daniels & Varghese, 2020; Kennedy, 2016). To be considered core, a practice should occur frequently, be adaptable to a variety of content areas and contents, be practicable by a novice, support students’ learning, allow teachers to learn about students, and preserve the complexity of teaching (Grossman et al., 2009b). Practice-based teacher education research has typically focused on in-class elements of disciplinary instruction, such as facilitating classroom discussions in social studies (Kavanagh et al., 2019) or helping students make sense of material activity in science (Windschitl et al., 2012). As indicated by other practices that have been considered “core practices”, such as establishing a safe space for students (Roberts & Olarte, 2023) and knowing students within and beyond school (Peercy et al., 2023), the focus on the content-based work of teaching is not exclusive. Although it has not typically been considered a core practice (exceptions include Khasnabis et al., 2018), family collaboration is the kind of complex work that practice-based teacher education aims to support. The inclusion of family collaboration as a core practice could open the door to a broader, more family-centric, model of teacher education and teaching.

In practice-based teacher education, core practices are typically taught through a series of representation, decomposition, and approximation in which teachers have an opportunity to observe the practice (representation), discuss its component parts (decomposition), and implement a scaffolded version of the practice (approximation) (Grossman et al., 2009a). In this way, teachers can see, consider, and attempt ambitious teaching strategies in a curated setting that enables intellectual exploration and provides greater safety than live pedagogical experimentation with and in front of students. Rehearsals, activities in which a teacher role plays a core practice in front of other learning teachers, are a common approximation that teacher educators use to prompt learning (Jay, 2023a; Kazemi et al., 2016). Although there is substantial space for teacher educator autonomy to dictate how approximations like rehearsals are conducted, debriefed, and experienced by teachers (Jay, 2024), an experience of authenticity and complexity is a key component of successful approximations (Kavanagh et al., 2025; Lampert et al., 2013). Too much complexity can be overwhelming at first (Stroupe & Gotwals, 2018), but a sense of realistic challenge is necessary to initiate reflective thinking, instances when authentic teaching merges with thoughtful cognition about teaching (Jay, 2023a; Schon, 1983). Although they have not previously been studied, authentic rehearsals of family communication have the potential to support preservice teachers’ development of the skills and beliefs that are necessary for equitable family–school collaboration.

2. Theoretical Framework

This study is grounded in Mapp and Bergman’s (2019) Dual Capacity-Building Framework for Family-School Partnerships. The framework synthesizes decades of research on family engagement in schools to articulate a model for collaborative family engagement. Although Mapp and Bergman designed their framework to describe the practices of in-service teachers, their analysis bridges to preservice teacher preparation. Aligned with national data on teacher preparation (National Association for Family, School, and Community Engagement, 2022), the authors attribute the common challenges of parent engagement to a failure of educator training. They argue that preservice education programs rarely engage in teaching about family engagement, thereby inadvertently sustaining a sense of alienation between schools and parents. To prepare teachers, families, and schools for equitable partnerships, the authors named four key competencies associated with successful collaborations: capabilities, connections, confidence, and cognition.

Mapp and Bergman described capabilities as “human capital, skills, and knowledge” and emphasized the need for “staff to be knowledgeable about the asset and funds of knowledge in the communities where they work” while “families need access to knowledge about student learning and the…school system” (Mapp & Bergman, 2019, Policy and Program Goals section). Connections refers to the network of relationships that foster family–school relationships and include parent-to-parent networks as well as relations and trust between families and the school. Confidence focuses on individual self-efficacy to engage in school–family collaboration for both families and teachers. Finally, Cognition refers to the assumptions and worldviews that value and foster school–family collaboration, including the beliefs that families have agency in a variety of roles in relation to students’ school experiences and that schools are receptive to family expertise. Mapp and Bergman’s articulation of these competencies is both retrospective and prescriptive. Because they see these competencies as present in existing successful partnerships, they offer them as appropriate aims for future attempts to bolster capacity for family–school partnerships. This study uses Mapp and Bergman’s framework as an articulation of the aims of teacher education. The instructional approach presented here is based on their vision of authentic, collaborative relationships between in-service teachers and families.

Research Questions

- How does engaging in role plays of family–school collaboration with families of schoolchildren provide opportunities for preservice teacher learning?

- How does engaging in role plays of family–school collaboration with preservice teachers provide opportunities for family participant learning?

- What do participants’ reflections on the activity indicate about the potential of the role plays for learning and advancing the goals of university-assisted community schools?

3. Methods

3.1. Study Context

This qualitative exploratory multiple case study (Stake, 2013) presents data from a pilot study aimed at supporting school–family communication within a teacher education program. Exploratory multiple case studies examine a shared phenomenon recurring across a number of instances. They are frequently used within teacher education, particularly in studies where scholars are not seeking to make causal claims but to explore the opportunities for and processes of teacher thinking, learning, and development (e.g., Dack & Ann Tomlinson, 2025; Gaines et al., 2018; Reisman & Jay, 2024). This study presents the experiences of multiple preservice teachers and family participants in a session of a preservice teacher education course intended to support families and teachers in developing the skills and disposition for collaboration.

The teacher education program is a three-semester graduate program in a public university in the northeastern United States. All secondary preservice teachers (PSTs) in the program are required to take a course in culturally responsive pedagogy taught by the first author. As part of the course, PSTs learned about engaging in collaborative problem-solving with students, colleagues, and families. In their university classroom, PSTs role-played conversations that could occur with students or co-workers. In those conversations, both sides of the dialog were performed by PSTs. This activity created a sense of emotional safety for PSTs as they experimented with different ways of engaging these conversations, but a low degree of authenticity.

To provide PSTs with authentic approximations of family communication, one session of the course traveled to a K-8 school to engage in simulations of school–family conversations with family participants (FPs), family members of children actually enrolled in the school. This school was selected because it is a university-assisted community school in a relatively low-income rural setting that was part of a pre-existing larger university partnership focused on fostering family agency. University-assisted community schools involve a “community of experts” comprising university faculty, families, students, school professionals, and community members who solve community-identified problems together (Cantor & Englot, 2013; Harkavy, 2023; Rimkunas et al., 2023). Not only did this existing partnership create an opportunity for collaboration aligned with the authentic goals of the school and community, it also marked the school as a site of genuine practice where the study itself became a family engagement event.

3.2. Data Sources

The course session on school–family communication was a three-hour class. During the first hour PSTs and FPs met separately to be briefed about the class, complete the informed consent protocol, and prepare for the scenarios. Each participant received the same four scenarios intended to reflect common situations in which teachers and family members might communicate (e.g., a positive phone call, academic concern, or a question about behavior) (Appendix A). The scenarios were intentionally open-ended to encourage participants to contribute vivifying details. Participants were also encouraged to create their own scenarios to discuss topics that they considered salient. PSTs were encouraged to approach the scenarios as a form of professional practice and an opportunity to try on the role of teacher. Recognizing the potential vulnerability of personal disclosure, FPs were given greater leeway and encouraged to consider whether they preferred to share personal experiences or play a character that they felt would help PSTs understand families’ needs. During the second hour of the class, PSTs and FPs formed triads with two PSTs to every FP and completed the scenarios with the PSTs alternating participant and observer roles. The final hour consisted of a debrief panel in which the entire group of FPs joined together to discuss the experience, provide feedback, and answer questions.

Data were drawn from three sources. First, PSTs who opted to participate in the study filmed their role plays with FPs. Leaving the camera running, these videos captured both PST and FP communication within their role plays, as well as conversations between PSTs and FPs when they stepped out of their character roles and addressed one another directly. These interval conversations often featured PSTs requesting evaluation and FPs offering advice. The second data source was the video of the formal debrief session after the role plays. This roughly hour-length video captured the FP panel during which FPs shared their experiences and answered questions from PSTs. Finally, PSTs and FPs completed brief written reflections after the activity.

3.3. Participants

All enrolled students (n = 22) were required to complete the role plays as part of their coursework, but participation in the study was optional. The eight PSTs who elected to participate filmed their role plays and completed short written reflections at the end of the class. All eight PSTs were students in their early 20s pursuing certification in mathematics education and who each held undergraduate degrees in mathematics or related fields. The study took place during the PSTs’ spring semester, which was the second semester of the three-semester master’s program. One participating teacher was working as a teacher of record on a short-term license. The rest of the group was in their second field placement of the year, a context in which they were charged with observing, not delivering, instruction. None of the PSTs reported practicing communication with families outside this experience, although the importance of family communication had been mentioned in at least two of their teacher education courses. Three of the PSTs were women and five were men. Seven of the PSTs identified as white, and one identified as Latino and biracial.

Although eight FPs consented to participate in this study, analysis for this paper only focuses on the six FPs who worked with participating PSTs. The two FPs who worked with PSTs who did not consent to the research study did not film their role plays. None of the FPs reported previously participating in teacher education, although the extensive history of the school’s community schools program meant that most had interacted with university programs or personnel in their school. The six focal FPs were white, in their 30s and 40s, and had children in the elementary or middle school. They included five women and one man. In addition to participating in the filmed role plays and debrief panel, FPs also completed a brief reflection form after the end of the session. All participants gave informed consent through the process approved by the institutional review board of the authors’ academic institution.

3.4. Data Analysis

Coding required transforming Mapp and Bergman’s (2019) four capacities into actionable codes capable of being applied across the videos of the role plays, the audio of the debrief panel, and the PSTs’ written reflections. As both PSTs and FPs were participants of interest, each code included a subcode differentiating between whether the coded utterance was said by a PST or FP (Table 1). The capabilities code was applied to statements in which the PSTs demonstrated skills for building rapport with families, knowledge of or appreciation for local communities, or recognition of the FPs’ expertise. When FP comments demonstrated their knowledge of school systems (e.g., grading calendars, special education procedures, etc.), an ability to build rapport with PSTs, or a presentation of communal assets, those comments were also coded as capability. The connections code was applied to comments in which PSTs or FPs demonstrated knowledge of parties beyond teachers and parents who might influence a child’s school life including school support staff, family members other than parents, and the broader community. Confidence codes were applied to statements that showed PSTs positioning themselves as capable of responding to FP’s needs, FPs asserting demands of the school, and any participant engaging the other through questions. Given the unique position of the FP in relationship to the PSTs and to their actual position within the school, instances in which FPs decided to disclose information about their own experiences as parents or to take on an explicitly instructional role in which they attempted to coach the PSTs were also coded as expressions of confidence. Although the dual-capacity framework articulated cognition in relation to growing trust in the school–family relationship, the temporary and improvisational nature of the role plays often meant that the PSTs and FPs were displaying cognition on a short-term and relational basis. Rather than coding for cognition about the superstructures of school that were often not present within the role plays, cognition codes were applied to statements in which the PSTs and FPs demonstrated they were actively responding to one another.

Table 1.

Codebook.

Analysis refined the codes through a recursive process (Miles et al., 2014). The two authors collaboratively coded two of the six role-play transcripts to establish coding definitions and norms. At that point, each author coded two of the remaining role-play transcripts independently, the authors met to resolve uncertainties, and Author 2 coded one of the debriefs. Once codes were established, each author coded half the transcripts at the level of the utterance. Utterances could be double-coded such that a single talk turn could be evidence of both cognition and connection, for example. Codes were applied to both the role plays and the debrief panel.

4. Results

The results of the analysis showed both groups of participants engaged in all four categories of collaboration named in Mapp and Bergman’s (2019) dual-capacity framework. The coding suggested that the PSTs primarily used the simulations to engage in realistic cognition, while the FPs were more likely to demonstrate their confidence and capability. On reflection, both sets of participants described the simulations as helpful. Based on these results, there is reason to believe that approximations like this have the potential to contribute to novice teachers’ and family members’ development as willing, skilled, and active participants in school–family collaboration.

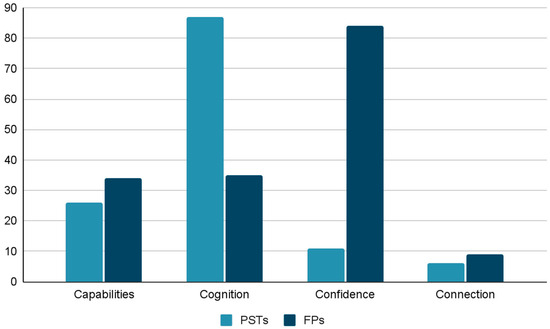

4.1. Preservice Teacher Candidates

The coding showed that the PSTs practiced all four of Mapp and Bergman’s (2019) key competencies for school–family collaboration during the role plays. Not only were 76 of the 115 coded PST utterances labeled cognition (66%) (Figure 1), but cognition was the most commonly applied code for each individual PST. Across the role plays, the PSTs solicited information from the FPs (“So I was wondering if you have noticed any changes in their behavior at home…I don’t know if [your child] has been feeling neglected or ostracized in my classroom. Have they mentioned anything like that to you?”), engaged the FPs as partners (“I was wondering if the two of us could collaborate moving forward to see if we could change that behavior”.), and asked the FPs for feedback (“I was just curious…if you felt like I was bombarding you to begin with”.).

Figure 1.

Percentage of PST and FP Comments During Role Plays by Code.

In two of the role plays with the greatest number of cognition codes, the PSTs directly engaged with the metastructure of the activity as an opportunity for learning. In one, the PST faltered at the start of a role play when the FP pressed her for more details about a student’s struggles in math class. Rather than push through, the PST realized that she was becoming flustered, broke off the simulation, and said, “Should we do it again?” After she identified that, “I was in a hole, because I was like, What am I saying?”, the FP and the other PST in the room started troubleshooting. Together, they problem-solved the scenario with the second PST suggesting “one-step equations” as a content area to focus on and the FP offering an extended bit of coaching in which she recommended scripting the first few sentences of future conversations. She said, “1000% be prepared. Yeah, have all your facts right in front of you…You can reset and look at your paper and be like, ‘Okay, we just need to address this’…like, take a breath and look at your paper and then come back up”. Weaving together the FP’s recommendation and her peer’s comments, the PST restarted the role play and delivered a fluid and specific response that ended with her and the FP collaboratively negotiating the next steps for the student. As soon as the role play ended, the PST started soliciting feedback again, saying “How was that?” and “Anything else you would recommend to do differently?” After the FP offered affirmation, the PST continued to ask, “What would be the best possible thing that a teacher would say back?” Across the role play, this PST was actively seeking and thinking about the FP’s perspective. Her cognition reflected an openness to the FP and a willingness to position herself as a learner.

A different PST demonstrated cognition with a similar willingness to incorporate FP feedback, although his articulation of cognition was less overt. In the first round of his role plays, he initiated a conversation with the FP about a generic concern about a student’s grades. After each participant made a few comments, the FP paused the role play and said:

I would want to see data…this is me as a true parent…I’d also want to ask about an evaluation, because there might be some special education needs…for accommodations [or] extra time…I know this because I have kids that have this [accommodation]…there’s a lot of parents that don’t ask for that.

Initially, the PST did not respond directly to her disclosure, instead finishing the role play by offering to “check in and make sure his homework is done” and asking about the student’s sleep schedule. In the next round, talking about a second student profile, the FP again stepped out of character to say, “Maybe we talk about an evaluation”. This time, the PST picked up the FPs’ recommendation and asked, “Would you be opposed to an evaluation?” From there he launched a series of questions about potential past encounters with special education to support the idea of an accommodation. In the third round, during a role play with non-academic concerns, the PST returned to the concept and asked, “Do you think it’s something where we would need to contact a school service if that’s impacting his whole educational performance?” Although all the participating PSTs had taken a course on special education the prior semester, this PST was the only one to discuss evaluation or additional special education support. While there appeared to be a lag in processing the FP’s coaching, the PST’s ability to incorporate feedback into his professional practice demonstrated his active thinking about the FP’s contributions and experiences.

In addition to their cognition, PSTs were also somewhat likely to demonstrate capabilities with six PSTs combining to make 24 total coded comments (21% of the PST comments). Most of the capabilities codes reflected the PSTs’ work to build rapport, including positive statements about students, such as “He’s coming in, smile on his face, and he’s really ready to go…I know in the past, he’s been a little hesitant to jump into the lesson, but he’s really been engaged and outgoing”, and proactive family engagement and familiar with school procedures like the PST who said, “If email isn’t the easiest way to contact, because I know that you’re probably busy with your own life…[I can] reach out either through [the school’s communications app] or I could give you my cell phone number”. One of the most extended displays of capability came from a PST engaged in a conversation about whether a student should be placed on an advanced track for math. The PST demonstrated a facility with school systems when he explained that “about 50% of our students take Algebra 2A and 2B in the two-year sections”, and showed flexibility in accommodating FPs when he agreed to put the student on the faster track, saying, “I think she’ll have a much better grasp and understanding of the content knowledge if she does this”. Rather than leave it there, the PST confirmed the plan with the FP and then summarized as follows:

Well, I think that that is a great idea. So for now, let’s tentatively say that we will, as long as her progress remains steady…we should put her into [the advanced class]…And I would absolutely like to stay in touch with you to make sure she’s still doing well at home and staying on top of her studies. And if she or you have any struggles or concerns, absolutely, you can voice them to me.

With this comment, the PST signaled their capability and commitment to being a bridge between school and family.

While PSTs frequently engaged in cognition and capabilities, they were less likely to express confidence and connections. These two competencies lagged well behind cognition and capabilities, with only 11 utterances coded as confidence (10% of the total coded PST comments) and 6 as connection (5%). The PSTs were most likely to make statements of confidence at the conclusion of a series of cognition statements. In these cases, their expressions of confidence served as capstones to exchanges in which they were listening to the FPs. For example, after an FP role-played being disappointed in the teacher’s responsiveness, a PST said, “[I can do better] actively reaching out…I’m sorry that the communication hasn’t been…as thorough as you’d like, there’s really no excuses for that. I am committed to every student doing the best they can”. His statement of his confidence in being able to improve professionally and support all students was a direct mirror of the cognition inspired by the FP. In this instance, and in most cases, the PSTs’ statements of confidence were more future-oriented than statements of present mastery. When connections emerged, they were typically references to other school staff such as guidance counselors or nurses (e.g., “I’ll [see]…when they can talk to the guidance counselor”.) and often came after FPs had recommended bringing those staff members into the conversation. Although they were comparatively rare, when confidence and connections were prompted by the role plays they emerged in response to FP suggestions. This pattern underscores the extent to which the PSTs were following the FPs’ suggestions, and intimates that confidence and connections may be developed along a similar trajectory as the other capacities.

4.2. Family Participants

The FPs also appeared to use the role plays, although in different ways than the PSTs. In their 127 coded comments, the FPs were substantially more likely to demonstrate confidence (49 instances or 39% of the FP comments) and capabilities (34 instances or 27% of the FP comments) than the PSTs (10% and 24% of the PST comments, respectively). Like the PSTs, the FPs often engaged in cognition (35 instances or 28% of the FP comments) and rarely mentioned connections (9 instances or 7% of the FP comments). The fluidity of the roles they took on, the wide latitude they had to position themselves, and the range of coded comments all seem to demonstrate that the role plays opened a number of ways for the FPs to practice communicating with the school.

The FPs displayed confidence more frequently than any other capacity. In some cases, the FPs displayed confidence directly, naming their own ability to initiate and sustain collaboration with teachers (“Because of my sister being a teacher, I’m like, ‘Help the teacher!’”). The most extensive displays of FP confidence, however, occurred when participants elected to reframe the discourse and step outside of the role plays to either share stories of their personal experiences as parents communicating with the school or to take on a coaching persona for the PSTs. Like the examples of the mother describing her experiences navigating the school’s special education system described above, personal disclosure was a way for the FPs to steer the PSTs and to share their own learning and knowledge. At the end of a role play in which the FP had suggested multiple instructional strategies for supporting a disengaged or distracted student, the FP elected to share how her actual parenting experience informed her role plays:

I’ve learned from teachers in the past, and I’ve been able to go the next year and go ‘Hey, if you have this issue this is what the last teacher did and it worked good.’ It saved time. We didn’t have to wait 10 weeks…into the year. For example, my son needs to be put up front…I learned that from one teacher and then the next year, I’m like, ‘Put him up front!’

For this FP, learning with and from teachers was not abstract, it was her experience. The FPs were not required or explicitly prompted to share personal details. The choice by several FPs to leverage their knowledge and experience for the role play demonstrated a level of confidence in their position as experts capable of teaching the PSTs.

At other points, the FPs became coaches, providing feedback and intentional challenges for the PSTs. One FP told her role-play partner, “I’m going to try to be mean this time…because you’re quiet and you need someone that’s going to confront you. I’m not normally like this”. Later, she asked the PST, “Is there one that you can think of that might scare you, or you don’t know how you would go about having that conversation with a parent?” After each round, she gave the PSTs feedback, at one point telling them, “You’re doing good, [but] you need to work on your eye contact”, and “You’re not listening to my feelings. I want to know that I’m being heard, and then I’ll like you more. 100% I’ll like you more. And if my attitude towards you is good, my kid’s is gonna be good”. She was not alone in her confidence in providing challenging feedback to the PSTs. Another FP pushed back on a PST’s framing of a conversation about behavior by saying, “If I’m a parent of a troubled child…and all of a sudden someone says to me, ‘Well, have you tried talking to them about it?’ I might feel very like, ‘Whoa, whoa, whoa. I’m the parent, don’t tell me what to do.’” A third FP entirely rejected a PST’s role play. This PST wanted to set the discussion about an academic concern at a baseball game, imagining that if he saw a parent on the sidelines of a game he could use that opportunity to talk about their son’s learning. The FP insisted that any issue with academics should prompt a phone call home and said, “If he’s failing absolutely [call home]. That’s a cause of concern. So that’s definitely something that if he is not doing good, grade-wise, and I don’t know about it until spring, I’m gonna be mad”. The FPs’ confidence in their expertise enabled them to work flexibly and responsively to extend the PSTs’ capacities, even when they were imagining the experience of parents unlike themselves.

The FPs’ capabilities and cognition emerged at similar rates during the role plays, and often in the same contexts as they demonstrated their ability to work with the PSTs, not just offer critique. Sometimes the FPs’ displays of capabilities came as affirmations. They said, “I think you approached it very calmly and nicely”, and “You did good. You communicated. I think honestly if a child was having showing difficulty…you as a teacher would already be recognizing and doing something about that, but letting the parent know what’s going on is very helpful”. They demonstrated their familiarity with school systems, having internalized the school calendar “I assume the first quarter grades already went out” and using multiple modalities for communicating with teachers, prompting the PSTs, “How are you letting me know that you even wanted to meet?…We have our [school communication] app that we use, [teachers often] shoot me like a direct message…are you going to send an email? Are you going to call me?” The FPs’ cognition often came as part of problem-solving with PSTs. For instance, one FP thought through the challenge of pushing too much homework upon a teenager, saying, “I don’t want to just be school, school, school, school, school. And no, like, free time either. Is there any way that we can find something [to balance]?” Often co-occurring with confidence, the capabilities and cognition codes showed FPs drawing upon their knowledge of schools.

Like the PSTs, the FPs rarely engaged in connections, only doing so nine times. Their comments mainly involved recommending that teachers use other school staff members as resources (“maybe we should reach out to a guidance counselor” and “have you talked with other teachers?”). One FP, however, discussed a connection in a negative light, describing a time when a teacher had offloaded the responsibilities of collaboration onto a coworker, rather than engaging the parent directly. She said, “I had this happen to me… [my son] came home with a huge gash on his face…I’m called from the nurse. I wasn’t called from the teacher…Don’t be that teacher that doesn’t warn their parents”. In most cases, the FP’s connections comments were also coded as capabilities and confidence as they used their knowledge of the school to direct PSTs.

4.3. Reflections

The data recorded during role plays presented an image of what the participants experienced as they spoke to one another. Data from the participants’ reflections, however, provided a wider lens on their experiences. The PSTs and FPs both reacted positively to the role play, but the differences in the content of their reflections may indicate divergent pathways toward longer-term learning. Additionally, the fact that the FPs’ reflections came during a debrief panel meant that their reflection was collaborative and provided additional opportunities for learning.

For the PSTs, the coding of their reflections reinforced the themes that emerged during the role plays. In their 20 coded comments, cognition (14 instances or 70%) and capabilities (4 instances or 20%) were the most frequent codes in their written reflections, while confidence (1 instance or 5%) and connections (1 instance or 5%) were rare. The PSTs directly attributed their active thinking to the authenticity of the experience, saying “Talking to an actual parent allowed for our conversations to be real” and “It was some of the most practical ‘work’ I have done thus far in the [teacher education] program because we were able to really practice the theories and concepts from all the courses”. For many of the PSTs, the arc of the experience was from anxiety to calm. One PST said, “I was a bit worried…I was not sure what to expect”. Another described herself as being “a little nervous”. A third said, “I was extremely nervous before this”. All told, six of the eight PSTs mentioned being nervous. Those expressions of uncertainty did not, however, appear to foreclose participation. On the contrary, the same PSTs who described themselves as nervous explained that the same uncertainty that worried them at the outset was part of what made them think on their feet, the authenticity triggered their cognition. For instance, the PST who was “a little nervous” also said she “really appreciated that the parent was confrontational and asked me tough questions” and felt that the FP “gave me helpful advice”. The PST who was “extremely nervous” also said the FP “made me feel comfortable right from the start” and “did a good job being tough or more lenient” based on what the PSTs needed to practice. As a different PST summarized, “As the conversations went on I felt my confidence grow”. Solidifying this trend, the PSTs expressed that the activity had increased their appreciation of parents. They said, “this really helped to open my eyes to the parent’s side of this”, “[this] makes me feel better about future conversations with parents”, and “I learned a lot about how to emphasize collaboration with parents”. All eight PSTs indicated a positive experience and increased openness to or preparation for school–family collaboration.

The FPs’ reflections during the debrief panel also mirrored their role plays. In their 57 coded comments, the FPs again primarily demonstrated confidence (35 instances or 61%) and, to a lesser extent, capabilities (13 instances or 23%) and cognition (11 instances or 19%). Unlike in the role plays, however, the FPs’ reflections demonstrated a growing rapport with one another and confidence in their identity as experts. Most of the comments coded to confidence were FPs talking about their preferences for teacher communication. For example, the FPs had a discussion amongst themselves about preferring that teachers communicate problems to them immediately. One FP said “it’s best to get to the parents as soon as you can, to let them know. You don’t have to have the solution. I think that’s sometimes why we don’t want to call because we can feel like we have to have the solution”. Several FPs agreed, one acknowledging that timely communicating means “we can talk about it and find a solution”.

A notable element of the debrief panel was the identity-building that occurred in the FPs. During the panel, the FPs began to respond to one another, sometimes in agreement to reinforce a position. For example, when an FP mentioned that teachers should reach out sooner when a problem arises with a student, the other FPs nodded in agreement and gave other examples. As the panel progressed, the FPs appeared to grow more comfortable in their role as experts and coaches to the PSTs. This was also demonstrated as cognition. One FP said they try to work together with the teacher when problems arise. The FP said “I want your input too about it, you know, because I’m not seeing what you’re seeing in the school. I want your aspect of the situation that’s going on, so that I can correct it the best that I can at home”. Several other FPs reinforced this, suggesting that teachers and parents need “clear communication” between them. Another FP agreed, telling the PSTs “We’re a team. The parents and teachers are a team. We both are looking for the same goal with our kids… Just talk to us, because we want to know. We want to help. We want to make sure that our kids are going to succeed too. So we’re a team”.

They were also comfortable disagreeing with one another, for instance, when discussing whether a school team should join a parent–teacher conference, or when talking about how the PSTs should be aware that eye contact may contribute to rapport-building with one parent but may intimidate another parent. Three of the FPs had a discussion amongst themselves about whether they preferred meeting with a school team or just the teacher. One FP suggested a scenario could include communication with a school team to say, “We all know your student, we see these behaviors, and we’re concerned”. This led to an exchange with another FP who disagreed, feeling that it would be overwhelming. They said, “I don’t like that. I wouldn’t want to be bombarded by more than one person, like, feeling like they were being defensive against one person, like, with a person with anxiety, you don’t want to be walking in and be bombarded by all these people from the school, yeah, telling you such a big problem”. Although they disagreed with each other, the FPs showed appreciation for their differences, which appeared to strengthen their collective identity.

Five FPs also shared their general reflections on the activity through an anonymous feedback form. All respondents said they would recommend the experience to other parents. One FP wrote “I enjoyed sharing my experiences and I hope they were helpful to the grad students”. Another said the experience would help PSTs understand that “parents and teachers are a team”. One FP affirmed that the interactions with PSTs were “welcoming and professional”, another felt the scenarios were “realistic”, and another felt that the PSTs were “receptive to all critique, positive and constructive”. When asked whether the activity should be required of new teachers, all FPs reinforced the utility of the exercise. One said it was important for PSTs to “get a feel for what parents would like to see” and another wrote that the activity “helps the grad students know that they need to be flexible, and what to look for”. Altogether, the experience seems to have been enriching for the PSTs and FPs.

5. Discussion

Mapp and Bergman’s (2019) framework for school–family partnerships is a prescription for future collaborations responding to a disheartening status quo. The need for better preparation for equitable community engagement emerged from a school-centric norm defined by either a lack of communication from schools or hierarchical relationships in which schools dictated to families (Ishimaru, 2019). Neither schools nor teachers are typically prepared for equal partnerships with families (De Coninck et al., 2018). In this study, however, the participants readily engaged in collaborative conversations, even without preexisting relationships. The PSTs may have been nervous to start the role plays, but, once they began, they worked hard to build rapport with the FPs and used their suggestions to improve their role plays. The FPs, for their part, extended themselves toward the PSTs as partners, mentors, and instructors. Their movement across multiple roles was a vivid embodiment of their expertise, and the comfort that enabled those flexible interactions may be a key ingredient in enabling equitable interactions. Building on these insights may help broaden the scope of teacher education and support making schools more family-centric.

5.1. Limitations

Sustained school–family collaboration requires a lasting change in teachers’ beliefs and behavior, families’ activity in relation to the school, and school structures to foster an ongoing relationship. This study is a snapshot of a teacher education course intended to support school–family collaboration, and the lack of longitudinal data collected here precludes addressing any questions about either families’ or teachers’ learning over the long term, or whether the insights from this class will transfer to a new school or setting. The PSTs in this study were not talking with the parents of students they really teach. At best, these role plays were an approximation of real collaboration, but it is entirely possible that the interactions we observed were performances intended to satisfy the requirements of their course and appease the FPs. Although the intention of the role plays was to support lasting shifts in practice and self-perception for both the PSTs and FPs, the artificial nature of the role play and the fact that data collection occurred during a limited window of time makes it difficult to determine whether the observed cognition codes reflect substantive reconsideration of their positionality as teachers, or the more superficial act of playing along. It is possible that the PSTs were merely performing responsiveness, but that the performance will not influence their future teaching outside the confines of the role play.

Additionally, given that all of the FPs and all but one of the PSTs were white, there is reason to wonder how the dynamics of the discussions might have been different in other communities or in cases of demographic mismatch between PSTs and FPs, particularly given the historical difficulty white teachers experience relating across those lines (Ishimaru et al., 2016), even within community schools (Baxley, 2022). Additionally, Mapp and Bergman (2019) theorized that successful partnerships require a commitment to collaboration at the administrative level of schools, but school leadership was not present within this pilot. At most, this study can serve as an evaluation of the potential of this kind of collaboration activity, not a proof of its effectiveness or replicability.

5.2. Supporting School–Family Collaboration

While all four capacities are intended to support family–school collaboration (Mapp & Bergman, 2019), cognition and confidence might be particularly important first steps for PSTs and FPs, respectively. As teachers and family members enter school settings, the differences in their positionality may mean that they face different initial barriers to engaging in collaboration. For teachers, who are empowered relative to parents and frequently carry deficit notions about the communities they serve (Azad et al., 2018; Symeou et al., 2012), learning to listen and trust the expertise of families is likely a prerequisite for any other forms of partnership. The opposite dynamic is often present for families, who can feel disempowered within schools (Froiland, 2020; Gonzalez-DeHass & Willems, 2003). This is particularly true in low-income communities, like the rural community in which this activity took place, where parents tend not to feel entitled to make demands of schools (Lareau, 2000). For families in these contexts, the possibility of partnership rests on their ability to enter the conversation.

The role plays were intended to provoke the PSTs’ cognition and the FPs’ confidence. Pairing parents with young and inexperienced preservice educators may have helped invert the established hierarchies within schools, making it easier for the FPs to feel in power and prompting the PSTs to be deferential. When the FPs described their experiences with special education evaluations, for instance, it may have been easier for the PSTs to recognize the expertise that parents were bringing to the conversation simply because the PSTs had no personal experience with the process. In this context, it is neither troubling nor surprising that the PSTs infrequently expressed confidence. Although Mapp and Bergman (2019) argued that teacher confidence is a necessary capacity for family–school collaboration, it is not necessarily true that confidence on its own is an inherent good. On the contrary, the literature on PSTs’ deficit orientation to families might mean that PSTs are typically overconfident in relation to the communities they serve, particularly when those families are low-income, multilingual, racially minoritized, or otherwise marginalized (Carter-Andrews et al., 2019). For this reason, the PSTs’ tendency toward cognition rather than confidence could be read as a success, evidence that they were authentically listening to and learning from families. Similarly, if FPs were more likely to express confidence than cognition, this might be a productive inversion of a relationship in which schools typically dictate parental thinking rather than listening to their expertise.

Beyond the presence of PST cognition and FP confidence, the lack of connections from both PSTs and FPs is concerning. The fact that the role plays were direct communication between teachers and families likely played a role in deemphasizing a broader constellation of staff and community members. Yet, research on community (Maier et al., 2017), family-centric (Pushor, 2015), and culturally responsive schooling (Ladson-Billings, 1995) emphasizes the importance of building networks that enable schools to become authentically and sustainably attuned to community needs. A critical analysis of schooling relies, in part, on the capacity to acknowledge the families’ and community’s funds of knowledge, the broader networks of trust, knowledge, and capacity that communities and individuals possess (Moll et al., 1992). The relative dearth of connections comments suggests that, at least in these interactions, the preservice teachers were not critically thinking about the resources, structures, and context of education within their community settings with criticality. The specificity of community strengths and needs is often the place where family expertise is most potent and teachers’ perspectives are most blinkered, yet they did not become direct topics of discussion within these role plays.

The role plays are not comprehensive in terms of all of the ways teachers and community members ought to interact. The research on teacher–community activism points to the importance of engagement outside the walls of the school (Oto, 2023). There may also be instances in which students may need teachers to act as allies shielding them from families, a circumstance that may be increasingly common with the politicization of school support for gender-diverse students (Hornbeck & Duncheon, 2024) and discussions of race and racism (LoBue & Douglass, 2023). The apparent utility of the role plays within the limited teacher–family relationship may be a jumping-off point for a more comprehensive engagement with the community.

5.3. Family-Centric Practice-Based Teacher Education

From a teacher education perspective, the results of the role play substantiate and extend the research on practice-based teacher education. The PSTs’ learning, as evidenced by their comments during the role plays and reflections afterward, confirms the core theoretical model of practice-based teacher education, while the application of this model to family–school collaboration suggests greater possibilities for family-centric applications of the practice-based model.

Practice-based teacher education research advances two key claims: that teachers can learn to judiciously implement core practices if they are deeply engaged in the enacted work of teaching and that scaffolded approximations of core practices can be authentic enough to spur that reflective learning (Grossman, 2018; McDonald et al., 2013). The role plays in this study were not truly examples of family–school collaboration, but they appeared to have enough authenticity to elicit the PSTs’ cognition, capabilities, and confidence. The PSTs’ reflections indicated that they felt increased confidence in their preparation family–school collaboration. Critically, they indicated both specific prompts and strategies they might use, as well as a general perception of parents as valuable partners. This connection between the practices and principles of family–school collaboration is precisely the kind of learning that practice-based teacher education research claims to enable (Grossman, 2018; McDonald et al., 2013). Furthermore, the PSTs’ reflections attribute that learning to the sense that the role plays were practical or real, which is to say that they experienced them as authentic. The results of this activity suggest that the practice-based model of teacher learning is not only generally useful, but that it is applicable to the orientations and skills of family collaboration.

Practice-based teacher education hinges upon the identification of which teacher practices are considered core, which is to say worthy of teaching with teacher education programs. When articulated too narrowly, the rich complexity of teaching is reduced to a technocratic set of best practices (Kavanagh et al., 2025). When drawn too broadly, the complexity is overwhelming and the act of instruction evaporates in a cloud of abstract principles and orientations. Much of the criticism of practice-based teacher education is not a response to the ideas that teacher education can and should prepare novices to thoughtfully implement specific pedagogies. Indeed, representations of practice are commonly used in a variety of teacher education contexts in the United States and internationally (Jay, 2023a; Jenset et al., 2018), and practice can be used flexibly to address a range of pedagogical opportunities and forms of reflective practice (Jay, 2024). Rather, a central element of the critique of practice-based teacher education stems from concern about which and in what ways core practices are defined. If core practices are derived from academic disciplines, they run the risk of assuming those disciplines’ hierarchical histories and attitudes (Zeichner, 2012). This study, then, offers an alternative vision of how core practice might be developed in a more family-centric approach.

More research is needed to hone this instructional possibility, to develop a model of teacher learning, and to consider how this approach might transform in different contexts. For teacher educators, approximations of practice pose a unique challenge. Their instructional potential stems, at least in part, from their authenticity (Jay, 2023b). If the conversations with the FPs were entirely scripted, the PSTs would not have been prompted to adapt and improvise. But allowing the role plays to be authentic requires teacher educators to relinquish control. They cannot hope to screen the FPs for particular perspectives or knowledges or to dictate precisely what the PSTs might experience or learn. Further experimentation in practice and research is needed to understand the pedagogical opportunities available in role plays like this. In particular, longitudinal research will be needed to understand how the experiences in a teacher education setting might be meaningful to future teacher thinking and action on a longer scale. Although questions about the long-term influence of teacher education are an ongoing concern for all practice-based teacher education work (Jay, 2024), the artificial structure of the role play makes these reservations particularly pressing in this case.

More information about how these PSTs go on to teach in their future settings will be important to better interpreting the data from this role play and similar teacher education experiences. Cognition within a role play may not predict future cognition outside of one. The PSTs’ mirroring back what an FP said to them may be more a feature of active listening than of thoughtful consideration and evaluation of what the FPs were asking of them. It is likely that the PSTs’ willingness to be accommodating was facilitated by the knowledge that they would not have to follow through on any of the offers of assistance or flexibility they made. Noting that the PSTs appeared to engage in active listening and reflection during the role plays is a more modest claim than asserting that the role plays guaranteed that the PSTs will become thoughtful teachers.

This work is embedded in context and community, and more needs to be done to understand how differences in setting may influence the process and learning. PSTs often leave their communities upon graduation to pursue jobs elsewhere. While PSTs may move on, families remain in their communities, sometimes engaging with the school for years to come. That itinerancy might undercut the efficacy of this activity, or it might spread the importance of family collaboration more widely. Longitudinal data will be necessary to truly evaluate the potential of the role plays.

5.4. Toward a More Family-Centric Schooling

Reformers seeking a more equitable school system have often looked to families and communities to set a new agenda for education (Fennimore, 2017; Love, 2019). Parents have deep knowledge of their children that can contribute to a student’s successful path throughout school (Gisewhite et al., 2019). Schools, however, often overlook parents’ knowledge and, instead, position them as clients rather than collaborators (Ishimaru, 2019; Shiller, 2020). Pushing against this trend, Ishimaru (2019) called for systemic capacity-building involving a culture of shared responsibility to engage families across a range of stakeholders, and specifically called for the inclusion of “nondominant parents as educational leaders who contribute and help shape the agenda” (p. 355). If the traditional operation of schools marginalizes parents and communities, then lasting change likely requires structural innovation.

University-assisted community schools, the setting and context for this study, are one institutional attempt to reorient schooling around and in service of families (Daniel et al., 2019; Harkavy et al., 2016; Heers et al., 2016). Transforming a traditional school into a community school requires an array of changes, including integrated student support, expanded learning time and opportunities, family and community engagement, and collaborative leadership and practices (Maier et al., 2017). But simply being involved in a community school does not automatically build teachers’ or families’ capacity for collaboration. Teachers and parents must acquire the skills to overcome the disconnected practices associated with traditional schools in order to foster genuine partnerships with one another and across ingrained systems of power (Rimkunas & Mellin, 2023; Sanders, 2018). Just as capacity-building has limited power without structural change, it would appear that structural changes also rely upon individuals’ capacity-building.

While this study did not engage at the level of structure or policy, its results suggest that partnership between teacher training programs and university-assisted community schools may unlock new opportunities for enhancing both programs and making both institutions more community-centered. Not only does this activity involve FPs in a teacher training program as experts, but this activity is inherently a family engagement initiative that yields mutual benefits for both PSTs and FPs. For PSTs, the benefits are in their learning, skill development, and growing confidence. For FPs, the potential advantages are more nuanced. By recognizing them as experts, this approach can value their funds of knowledge and time—not only by PSTs but also by the partnering school, researchers, and fellow FPs. Future research on this model could examine whether and how FPs translate their demonstrated confidence into future school communication.

The potential benefits of this activity also extend to the school and university. In designing and implementing this study, the authors engaged school leadership, whose involvement in the pilot suggests the potential for deeper, long-term collaboration, which is a priority of university-assisted community schools. The university also benefits by building trusting relationships with families and actively advancing its mission to promote high-impact educational experiences and community engagement through scholarship and practice. This type of engagement lays the groundwork for establishing a truly collaborative and continuous program of PST development and long-term partnership with schools. Recognizing the mutually reinforcing potential for structural change and individual capacity-building, the findings of this study highlight the opportunity to engage families meaningfully in schooling and teacher education while also strengthening the theoretical case for long-term investment in this approach.

Author Contributions

Both listed authors contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and writing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by internal funding provided by Binghamton University’s Center for Civic Engagement and College of Community and Public Affairs.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Binghamton University (Protocol code STUDY00005766 approved on 3 December 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request to the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

- Family–Teacher Role Play Scenarios

Families: We want these conversations to feel real for teachers. Before you begin your discussion with teachers, imagine what might be going on in this students’ life. Decide what emotions you will bring into the discussion. Does the news surprise you? Delight you? Make you angry? Is your child responsible for solving the problem? Is the school? Are there other things going on in this child’s life that might matter? Use your real experience as a family member, but feel free to be an actor.

Scenario 1: Imagine that it is the end of December and a student, C. is failing your class. C. is funny and kind to both teachers and peers, but they rarely participate in class, sometimes sleep or have their phone out, and often need to be prompted to complete class work. They turn in homework about 75% of the time. Their low grade is largely due to their poor scores on tests and projects.

Scenario 2: Imagine that at the start of class, two students, S. and J. got into an argument. It seems that S. was sitting in J.’s usual seat. The argument was loud, but not physical or dangerous. To get class started, you asked both S. and J. to step into the hall so you could speak to them. J. walks to the hall quickly, but S. makes a scene, knocking J.’s possessions off the desk, yelling “This isn’t fair. You’re always picking on me!”, and refusing to talk to you or make eye contact.

Scenario 3: Imagine that it is the end of October. A student, R. is thoughtful, eager, and generous with their peers. At times they struggle with the academic material, but they are usually willing to take risks and are attentive in class. They have been absent five times this semester.

Scenario 4: Imagine that you have noticed a change in C’s behavior. He has become more engaged, outgoing, and determined to complete his classwork. OR Families can create their own scenario in which they might call the teacher.

For each scenario, teachers will script an introduction and a series of follow up questions. Families will script potential responses for a 5–10 min conversation.

References

- Alaçam, N., & Olgan, R. (2019). Pre-service early childhood teachers’ beliefs concerning parent involvement: The predictive impact of their general self-efficacy beliefs and perceived barriers. Education, 47(5), 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, G. F., Marcus, S. C., Sheridan, S. M., & Mandell, D. S. (2018). Partners in school: An innovative parent-teacher consultation model for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 28(4), 460–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxley, G. (2022). Community schooling for whom? Black families, anti-blackness and resources in community schools. Race Ethnicity and Education, 27(6), 875–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantor, N., & Englot, P. (2013). Beyond the “Ivory tower”: Restoring the balance of private and public purposes of general education. The Journal of General Education, 62(2–3), 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter-Andrews, D. J., Brown, T., Castillo, B. M., Jackson, D., & Vellanki, V. (2019). Beyond damage-centered teacher education: Humanizing pedagogy for teacher educators and preservice teachers. Teachers College Record, 121(6), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dack, H., & Ann Tomlinson, C. (2025). Preparing novice teachers to differentiate instruction: Implications of a longitudinal Study. Journal of Teacher Education, 76(1), 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, J., Quartz, K. H., & Oakes, J. (2019). Teaching in community schools: Creating conditions for deeper learning. Review of Research in Education, 43(1), 453–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, J. R., & Varghese, M. (2020). Troubling practice: Exploring the relationship between whiteness and practice-based teacher education in considering a raciolinguicized teacher subjectivity. Educational Researcher, 49(1), 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Coninck, K., Valcke, M., & Vanderlinde, R. (2018). A measurement of student teachers’ parent–teacher communication competences: The design of a video-based instrument. Journal of Education for Teaching, 44(3), 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J. L. (2018). School, family, and community partnerships in teachers’ professional work. Journal of Education for Teaching, 44(3), 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J. L., Sanders, M. G., Sheldon, S. B., Simon, B. S., Salinas, K. C., Jansorn, N. R., & Voorhis, F. L. (2018). School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action (4th ed.). Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fennimore, B. S. (2017). Permission not required: The power of parents to disrupt educational hypocrisy. Review of Research in Education, 41(1), 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froiland, J. M. (2020). A comprehensive model of preschool through high school parent involvement with emphasis on the psychological facets. School Psychology International, 42(2), 103–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaines, R., Choi, E., Williams, K., Park, J. H., Schallert, D. L., & Matar, L. (2018). Exploring possible selves through sharing stories online: Case studies of preservice teachers in bilingual classrooms. Journal of Teacher Education, 69(3), 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisewhite, R. A., Jeanfreau, M. M., & Holden, C. L. (2019). A call for ecologically-based teacher-parent communication skills training in pre-service teacher education programmes. Educational Review, 73(5), 597–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-DeHass, A. R., & Willems, P. P. (2003). Examining the underutilization of parent involvement in the schools. School Community Journal, 13(1), 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, P. (Ed.). (2018). Teaching core practices in teacher education. Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grossman, P., Compton, C., Igra, D., Ronfeldt, M., Shahan, E., & Williamson, P. (2009a). Teaching practice: A cross-professional perspective. Teachers College Record, 111(9), 2055e2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, P., Hammerness, K., & McDonald, M. (2009b). Redefining teaching, re-imagining teacher education. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 15(2), 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkavy, I. (2023). Dewey, implementation, and creating a democratic civic university. The Pluralist, 18(1), 49–75. Available online: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/882453 (accessed on 19 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Harkavy, I., Hartley, M., Axelroth Hodges, R., & Weeks, J. (2016). The history and development of a partnership approach to improve schools and communities. In H. A. Lawson, & D. Van Veen (Eds.), Developing community schools, community learning centers, extended-service schools and multi-service schools (pp. 303–321). Springer Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Heers, M., Van Klaveren, C., Groot, W., & van den Brink, H. M. (2016). Community schools: What we know and what we need to know. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1016–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornbeck, D., & Duncheon, J. C. (2024). “From an ethic of care to queer resistance”: Texas administrator and teacher perspectives on supporting LGBTQ students in secondary schools. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 37(3), 874–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, A. M. (2019). From family engagement to equitable collaboration. Educational Policy, 33(2), 350–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, A. M., Torres, K. E., Salvador, J. E., Lott, J., Williams, D. M. C., & Tran, C. (2016). Reinforcing deficit, journeying toward equity: Cultural brokering in family engagement initiatives. American Educational Research Journal, 53(4), 850–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobbe, T., Ross, D., & Hensberry, K. (2012). The effects of a family math night on preservice teachers’ perceptions of parental involvement. Urban Education, 47(6), 1160–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, L. P. (2023a). Constructing imaginary classrooms: Teacher educators’ use of representations to direct reflection about practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 132(1), 104243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, L. P. (2023b). What do social studies methods instructors know and do? Teacher educators’ PCK for facilitating historical discussions. Theory & Research in Social Education, 51(1), 72–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, L. P. (2024). A framework for approximations of practice: Variations in purpose, approach, and opportunities for learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 152(1), 104795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenset, I. S., Klette, K., & Hammerness, K. (2018). Grounding teacher education in practice around the world: An examination of teacher education coursework in teacher education programs in Finland, Norway, and the United States. Journal of Teacher Education, 69(2), 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, S. S., Gotwalt, E. S., Guillotte, A., & Bernhard, T. (2025). Differentiating between core practices and best practices: Exploring divergent purposes for developing a professional language for teaching. Teachers College Record, 126(11), 59–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, S. S., Monte-Sano, C., Reisman, A., Fogo, B., McGrew, S., & Cipparone, P. (2019). Teaching content in practice: Investigating rehearsals of social studies discussions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86(1), 102863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, E., Ghousseini, H., Cunard, A., & Turrou, A. C. (2016). Getting inside rehearsals: Insights from teacher educators to support work on complex practice. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(1), 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M. (2016). Parsing the practice of teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 67(1), 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasnabis, D., Goldin, S., & Ronfeldt, M. (2018). The practice of partnering: Simulated parent–teacher conferences as a tool for teacher education. Action in Teacher Education, 40(1), 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory into Practice, 34(3), 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, M., Franke, M. L., Kazemi, E., Ghousseini, H., Turrou, A. C., Beasley, H., Cunard, A., & Crowe, K. (2013). Keeping it complex: Using rehearsals to support novice teacher learning of ambitious teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(3), 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareau, A. (2000). Home advantage: Social class and parental intervention in elementary education. Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- LoBue, A., & Douglass, S. (2023). When white parents aren’t so nice: The politics of anti-CRT and anti-equity policy in post-pandemic America. Peabody Journal of Education, 98(5), 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]