Abstract

Teachers’ beliefs on issues of multilingualism shape their classroom practices, which in turn affect their multilingual students’ learning opportunities and academic achievement. Examining these beliefs is therefore crucial for teacher educators who strive to equip pre- and in-service teachers with the appropriate mindset that is necessary in the context of an educational landscape characterized by linguistic diversity. In this study, we examine German pre-service teachers’ knowledge of and beliefs toward multilingualism and their perceived preparedness for a multilingual classroom. We use a questionnaire that includes an internationally recognized scale to measure beliefs toward multilingualism Additionally, we investigate how a semester-long lecture on German as a second language (GSL) and language-sensitive teaching influences pre-service teachers’ beliefs. The results indicate that while German pre-service teachers demonstrate knowledge and awareness of multilingualism, there remains potential for fostering a more open belief system—one that is essential for effectively engaging with diverse student groups and should be systematically addressed during university education. Pre-service teachers who participated in the semester-long lecture showed slightly more multilingual beliefs. These findings provide a basis for discussing curricular opportunities aimed at promoting multilingualism and supporting language learning in educational settings.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, Europe has witnessed a significant influx of migrants from diverse backgrounds, resulting in a linguistically heterogeneous student body in classrooms. This development is particularly pronounced in German classrooms, as Germany has been the main destination country for individuals and families searching for better opportunities, not just recently, but since the 1950s (bpb, 2023). About one fourth of the population of Germany has a family history of migration. Among children under the age of six, 28% either have parents who were born abroad or were born abroad themselves. Notably, 85% of these children were born in Germany (Federal Education Report, 2024). Given the increasing linguistic diversity in German classrooms, every teacher must now be prepared to address the associated challenges. Meeting the (language) needs and unfolding the full potential of linguistically diverse students require teachers to acquire a different set of skills (Lucas & Villegas, 2013; Morris-Lange et al., 2016; Witte, 2017). One important pre-requisite for implementing changes in pedagogy is a positive view toward the multilingualism of the students.

The present study examined both the preparedness for the multilingual classroom and the beliefs pre-service teachers hold regarding multilingualism and multilingual students. Further, it investigated the beliefs of pre-service teachers before and after a lecture in German as a second language (GSL) and language-sensitive teaching.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Preparedness for the Multilingual Classroom

A survey among 512 teachers from various school types across Germany revealed that the majority of teachers (66%) feels unprepared to work with heterogeneous student groups, despite 83% of teachers reporting that they teach multilingual students and 70% indicating that they work with students who have language support needs. Notably, 82% of respondents state that language must be fostered by all teachers, not just language experts, such as teachers of German (Becker-Mrotzek et al., 2012). More than a decade later, Kaplan (2023) similarly reported that 82.5% of 40 pre-service teachers across different school types agree that fostering language development is the responsibility of all teachers, regardless of their subject area.

Michalak (2010) observed in a survey on the support of children with GSL that two-thirds of the 32 pre-service teachers surveyed felt scarcely prepared to address the challenges related to the German language or to apply current methods and didactic approaches to language support. Yet, even in 2023, 45% of pre-service teachers still report uncertainty when dealing with linguistically heterogeneous classrooms (Kaplan, 2023).

2.2. Beliefs

In addition to formal preparation through university education, the altered circumstances also require teachers to adopt a specific mindset (Lucas & Villegas, 2013; Morris-Lange et al., 2016). Beliefs can be defined as “implicit or explicit systems of claims that an individual accepts as true” (Gallagher & Scrivner, 2024, p. 2). While a universally accepted definition of beliefs is still missing (Dohrmann, 2021), there is broad consensus on two essential characteristics on beliefs: (1) they are subjective and primarily shaped by teachers’ personal experiences within the education system, and (2) they influence teachers’ perceptions, evaluations, and instructional decision-making (Reusser & Pauli, 2014).

Teachers’ beliefs are regarded as a key component of teachers’ professional competence, as outlined in the COACTIV-model (Baumert & Kunter, 2011). According to this model, effective instruction is not solely determined by pedagogical content knowledge, as had long been assumed, but also by other factors, such as the beliefs that teachers hold, which significantly influence professional teaching behavior. In linguistically diverse classrooms, these beliefs gain particular relevance. They guide how teachers perceive students’ language resources and shape their openness toward multilingualism. They are also important since they are found to shape classroom practices, such as adequately selecting teaching methods and materials, implementing scaffolding techniques in content learning, and valuing and promoting multilingualism by establishing multilingual students’ heritage languages as a means of learning. Moreover, teachers’ beliefs are considered to impact multilingual students’ experiences and educational outcomes, thereby contributing to the overall inclusivity and effectiveness of education in linguistically diverse settings. Reusser and Pauli (2014) highlighted the importance of teachers’ beliefs when they suggested that “beliefs matter” (p. 655), particularly in terms of high-quality instruction, i.e., instruction that efficiently fosters students’ learning independently of their background. In light of the increasing linguistic diversity in educational settings in Germany, exploring teachers’ beliefs is therefore essential for their professional development.

Teachers’ beliefs have been investigated in the German schooling context for some time now (for an overview, see Fischer, 2020). More recently, an increasing number of studies have focused specifically on teachers’ beliefs regarding multilingualism (Fischer, 2020). One of the earliest and most influential contributions in this area is Gogolin’s concept of the “monolingual habitus”, which continues to inform current research on language education in linguistically diverse classrooms. Gogolin (2008) argues that deeply rooted monolingual beliefs have existed in the German school system for nearly two centuries and attributes them to sociopolitical developments initiated during the processes of nation-building. Based on the results of her survey conducted with 185 teachers, she coined the term “monolingual habitus” to describe the strict monolingual orientation of (language) education reflected in policies, curricula, and didactics, to which her participants predominantly had been adhering in their daily routines, despite working in linguistically diverse classrooms. Importantly, Gogolin (1997) argues that the phenomenon of a “monolingual habitus” is not unique to Germany but can be found in all states with a European tradition of nation-state formation. In many European countries, historical multilingual realities were increasingly suppressed during nation-building processes in favor of establishing unified national languages. Thus, the marginalization of linguistic diversity emerged as a widespread historical pattern across much of Europe.

At the same time, Gogolin’s concept critically highlights the persistence of monolingual biases in an era of increasing global migration, during which a growing proportion of students in Germany and elsewhere have a first language other than the national language(s). Her findings have laid the foundation for subsequent research into teachers’ beliefs about linguistic diversity and the challenges of fostering equitable educational opportunities for multilingual students. Building on these insights, more recent studies have explored various factors that influence teachers’ beliefs toward multilingualism.

2.3. Factors Influencing Beliefs

Several studies from Germany and in the international context have demonstrated that training related to multilingualism can influence teacher’s beliefs (e.g., Alisaari et al., 2019). For instance, a study conducted at German universities found that participation in a GSL program led to improved language-sensitive practices (Fischer & Ehmke, 2019; Hammer et al., 2016). Similarly, Pohlmann-Rother et al. (2023) found that only elementary school teachers who invested substantial time in pre-service training on multilingualism developed more positive beliefs. Gallagher and Scrivner (2024), on the basis of their systematic review in the US context, emphasize that pre-service diversity coursework has also been shown to play a role in valuing linguistic diversity. This supports the broader assumption that targeted academic preparation can contribute to the development of more multilingually oriented beliefs among future teachers.

The relevance of such preparation becomes evident when considering generational differences in teachers’ beliefs. Older teachers have been found to hold less favorable beliefs toward linguistic diversity (Bernstein et al., 2021; Flores & Smith, 2009; Metz, 2019). This generational gap likely reflects a reduced exposure to recent developments in teacher education and the fact that their initial teacher education may have provided fewer opportunities for structured reflection on linguistic diversity. Moreover, they may have been trained at a time when monolingual norms were less frequently questioned. In contrast, pre-service teachers in recent programs often encounter more explicit engagement with multilingualism and are thus better equipped to adopt inclusive and resource-oriented approaches in their teaching.

That such pedagogical preparation is essential is further highlighted by evidence from countries with formally inclusive language policies. Vikøy and Haukås (2023), for example, found that Norwegian L1 teachers frequently held problem-oriented beliefs toward multilingualism, despite working within a curriculum that explicitly promotes linguistic diversity. Although the curriculum formally promotes linguistic diversity, teachers perceived students’ home languages as obstacles rather than resources—a belief that is partly rooted in the lack of concrete guidance and practicable teaching materials for multilingual pedagogy. These findings highlight that progressive policy frameworks alone are insufficient unless accompanied by systematic support and concrete pedagogical training within teacher education.

Another contributing factor is teachers’ own backgrounds. In a comparative cross-sectional study, Hachfeld et al. (2012) found that multicultural beliefs (as opposed to egalitarian beliefs) were more pronounced among teachers in training (this is the practical training period following university training) who had a multilingual or migrant background than among those who had grown up monolingually or monoculturally. This, in turn, was associated with greater openness toward multilingual students. Similar results have been reported by Schroedler and Fischer (2020).

Gallagher and Scrivner (2024) confirm these patterns across multiple studies: teachers with multilingual biographies were more likely to be multilingually oriented, while those socialized in monolingual contexts often normalized monolingual beliefs. At the same time, the authors highlight that not all multilingual teachers adopt positive beliefs—individual trajectories and family experiences, such as pressure to assimilate linguistically, may moderate this relationship.

Further life experiences, such as racial or ethnic identity, geographic background, and personal schooling histories, have also been found to shape beliefs (Gallagher & Scrivner, 2024). Teachers from minoritized groups or from linguistically diverse regions were more likely to support home language maintenance and reject monolingual ideologies. Also, teachers who had been exposed to linguistic diversity during their own schooling tended to express more empathetic and supportive views toward multilingual students. Such experiences appear to increase sensitivity to the challenges faced by those students and foster greater openness to inclusive language practices.

In addition to professional training and biographical background, teachers’ classroom experiences with multilingual students have a strong influence on their beliefs. Studies from both German and international contexts (e.g., Lucas et al., 2015; Pohlmann-Rother et al., 2023) suggest that regular engagement with linguistically heterogeneous student groups correlates with more supportive beliefs. These findings are echoed by Gallagher and Scrivner (2024), who conclude that teaching experience, per se, appears to be less influential than direct engagement with multilingual students during teacher education (for instance through tutoring or classroom observation). First-hand experience with linguistic diversity thus seems to foster openness and more open beliefs toward multilingualism more effectively than the accumulation of teaching years alone.

The school subjects studied (e.g., language or non-language related subjects) may further moderate these dynamics by shaping exposure to multilingual contexts. Pre-service teachers specializing in German as a second language—or in second/foreign language teaching more broadly—are regularly confronted with linguistic heterogeneity, both theoretically and practically, than those in non-language tracks. Consequently, they tend to adopt more multilingually oriented beliefs (Paetsch et al., 2023; Lucas et al., 2015). This indicates that subject-specific trajectories not only reflect but actively shape the experiential foundations upon which beliefs develop.

These subject-specific trajectories are also closely linked to teachers’ linguistic biographies. According to Calafato (2020), teachers who identify as multilingual and engage with multiple languages in their teaching are significantly more likely to perceive multilingualism as a valuable pedagogical resource and to challenge monolingual norms. Their beliefs are not solely shaped by their language proficiency but are also influenced by their professional experiences, social language ideologies, personal identities, and societal support structures—highlighting the complex interplay between language experience, instructional context, and broader sociopolitical factors in shaping multilingual beliefs.

In addition to these individual and contextual factors, demographic variables also play a role. Gender has been repeatedly associated with differing beliefs. Female teachers are more likely to express positive views and show greater openness toward linguistic diversity (Lundberg, 2019b; Schroedler et al., 2023; Schroedler & Fischer, 2020). While the underlying mechanisms require further investigation, this pattern suggests that gender may influence how linguistic diversity is perceived and addressed in educational settings.

While individual characteristics are important, a range of structural factors also shape teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism. Gallagher and Scrivner (2024) identify several key contextual influences based on their review of empirical studies. First, curricular demands tend to narrow teachers’ language focus on the standard language, discourage the inclusion of students’ home languages in instruction, and foster the belief that the presence of multilingual students in mainstream classrooms slows down instructional progress. Second, beliefs are often aligned with school contexts, including the linguistic composition of the student body, prevailing school language policies, and the perspective of school leadership. Teachers report experiencing tension when their own beliefs conflict with institutional demands, illustrating the complex interaction between personal conviction and systemic pressures. Finally, access to resources—particularly time and linguistically/culturally responsive teaching materials—was found to significantly affect teachers’ willingness and ability to address multilingualism in their classrooms. Taken together, these findings underscore that beliefs are not static or isolated but embedded in broader sociopolitical and institutional frameworks.

While numerous factors have been found to shape teachers’ beliefs, these beliefs themselves are not without consequences. Research indicates that teachers’ beliefs about language diversity and multilingual students significantly influence their instructional practices (Gallagher & Scrivner, 2024). Specifically, teachers who hold multilingually oriented beliefs—viewing students’ home languages as assets—are more likely to implement equitable and supportive teaching strategies. Conversely, teachers with less multilingually oriented beliefs—seeing students’ languages as deficiencies—tend to adopt practices that may suppress or devalue students’ linguistic backgrounds. Overall, the findings emphasize that a teacher’s underlying beliefs about language directly shape how they approach classroom language use, differentiation, and assessment, affecting their ability to create an inclusive environment for multilingual students.

An important study in this context was conducted by Pulinx et al. (2017) in Flanders (Belgium). Using an innovative scale based on eight statements (the so-called “monolingualism scale”), the authors investigated secondary teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism. Their results showed that teachers in the sample had particularly pronounced monolingual beliefs, as reflected in their responses. On a five-point scale (1 = most multilingually oriented beliefs; 5 = most monolingually oriented beliefs) teachers scored, on average, 3.74 points. Responses to the individual items showed that, e.g., only 12% agreed that students should be offered the opportunity to learn their home languages at school, and almost 30% stated that students should be punished for using their home language at school. Further in-depth analyses revealed that male teachers expressed more monolingual beliefs than female teachers and that the highest levels of monolingual beliefs were observed in schools with an ethnically balanced student population. Crucially, the study found that the more pronounced teachers’ monolingual beliefs were, the lower their expectations toward their students were. Given the well-established positive correlation between teachers’ expectations and students’ academic achievement, this finding is relevant. Monolingually oriented beliefs, therefore, risk contributing to the reproduction of educational inequalities for multilingual students, both in the short term (e.g., through biased grading practices) and in the long term (e.g., by limiting access to higher education, employment, and social participation).

In a subsequent study using the same “monolingualism scale”, Bosch et al. (2024) demonstrated that elementary school teachers from three different European countries (Greece, the Netherlands, and Italy), where a comparably high number of multilingual students attend schools, expressed clearly less pronounced monolingual beliefs on issues of multilingualism than their Belgian counterparts (2.17 in Greece, 2.62 in Italy, and 2.62 in the Netherlands). Greek teachers expressed the most multilingually oriented beliefs, while in Italy and the Netherlands, beliefs tend to be cautiously positive but are potentially affected by policy ambiguity and variable teacher training (Bosch et al., 2024). The authors could further show that training on multilingualism positively affected teachers’ beliefs in all three countries.

The study’s results are, however, not entirely (methodically) comparable with the findings by Pulinx et al. (2017) for two reasons: (1) The sample of Bosch et al. (2024) exclusively consisted of elementary school teachers whose beliefs on issues of migration-related multilingualism seem to be more positive toward language in general than secondary school teachers’ beliefs, which may be due to working with younger children on issues of language and reading/writing acquisition (as discussed in Bosch et al., 2024). (2) There was also a relatively high proportion of female teachers (average across all countries: 89%), while in Pulinx et al. (2017), 62.5% of participants were female. This might have biased the results due to an evident gender effect, which has also been reported elsewhere (see above).

2.4. Policy Changes in Germany

Germany, as the European country with the highest number of residents with a migration background, has witnessed increasing attention to linguistic diversity in educational discourse. Nevertheless, monolingual norms continue to dominate teacher education and classroom practices (Gogolin, 2008). Compared to Greece, where inclusive language policies and direct experience with multilingual students foster particularly supportive beliefs among teachers, pre-service teacher education in Germany has been found to still need improvement. Teacher education programs across all federal states still require further development to adequately prepare future teachers for linguistically diverse classrooms, as emphasized in a policy brief by a German expert panel (Morris-Lange et al., 2016; see also Lucas & Villegas, 2013). In recent years, many universities have introduced programs to strengthen the competences with respect to multilingualism, to varying degrees (from obligatory training for all teacher education students to training, e.g., in Berlin or North Rhine-Westphalia, to additional classes only for future teachers of German, e.g., in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg). Studies have reported varying degrees of success with these programs (e.g., Andresen & Lahmann, 2020; Born et al., 2019).

This paper focuses on pre-service teachers in Germany, investigating their (perceived) preparedness for the multilingual classroom, as well as their self-assessment of their role in the context of their beliefs (using the belief scale developed by Pulinx et al., 2017). This study was conducted at two German universities (here named “A” and “B”) in southern Germany and included pre-service teachers preparing to teach at the “Gymnasium” level—the highest track in the German secondary school system, typically lasting eight or nine years and culminating in the “Abitur”, which qualifies students for entry into higher education. Participants at University A were training to teach various subjects, including both language and non-language subjects. In contrast, the group from University B consisted of students studying to become German teachers exclusively and attending a five-credit course (lecture) on GSL and language-sensitive teaching.

Our research questions/hypotheses are as follows:

- (1)

- How well-prepared do German pre-service teachers feel for teaching in linguistically diverse classrooms? In line with earlier findings (Becker-Mrotzek et al., 2012; Kaplan, 2023), a larger proportion of pre-service teachers is expected to report feeling prepared or well-prepared. Also, based on previous research (Hachfeld et al., 2012; Fitzsimmons-Doolan, 2014; Fitzsimmons-Doolan et al., 2017; Lundberg, 2019a; Paetsch et al., 2023), pre-service teachers who study language-related subjects, are female, or have a multilingual background are expected to feel better prepared for working in heterogeneous classrooms.

- (2)

- How do the beliefs of German pre-service teachers toward multilingualism compare to those of teachers in Belgium, Greece, Italy, and the Netherlands? German pre-service teachers are hypothesized to occupy a moderately supportive position—more open than Belgian teachers, less open than Greek teachers, and like those in Italy and the Netherlands. As in the Belgian sample, the participants in this study are training to become Gymnasium teachers, a track that is traditionally characterized by a more academic and less pedagogically oriented focus. Therefore, they are also expected to show lower openness toward linguistic diversity in the classroom.

- (3)

- Which individual characteristics influence pre-service teachers’ beliefs toward multilingualism, as measured using the “monolingualism scale” (Pulinx et al., 2017)? Based on previous research (Hachfeld et al., 2012; Fitzsimmons-Doolan, 2014; Fitzsimmons-Doolan et al., 2017; Lundberg, 2019a; Paetsch et al., 2023), it is expected that gender, multilingual background, and the study of language-related subjects will significantly influence beliefs. Specifically, female participants, those with a multilingual background, and those studying at least one language subject (e.g., German, English, French, Spanish) are expected to hold more multilingually oriented beliefs.

- (4)

- Does participation in a single university lecture on GSL influence pre-service teachers’ beliefs towards multilingualism? In line with previous studies showing that training can affect teachers’ mindsets (e.g., Alisaari et al., 2019; Fischer & Ehmke, 2019), it is expected that pre-service teachers who attend a mandatory lecture on GSL will show more multilingually oriented beliefs after the lecture than before.

3. Materials and Methods

Data for this study was collected as part of a larger research project (“Fostering Academic Language: New Perspectives on German as a Second Language in the Classroom”) in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg in southern Germany. In this region, the proportion of individuals with a migration background (30.9%) is slightly higher than the national average (Baden-Württemberg Statistical Office, 2023).

A total of 118 pre-service teachers from University A participated; at University B, 149 pre-service teachers filled out the same questionnaire before attending a newly introduced lecture on GSL and language-sensitive teaching, with 81 participants also completing it again after the course. The lecture was mandatory for pre-service teachers of German and was part of the regular curriculum. It was primarily lecture-based but contained interactive elements, such as partner work on second language development or group discussions on how to integrate multilingualism into the classroom. The course was taught by the first author of this paper as part of her teaching assignment at University B.

Participation in the study was voluntary. By completing the questionnaire, all respondents gave informed consent for the data to be used in scientific publications. According to the university policies, Ethics Committee approval was not required for this type of anonymous questionnaire study involving consenting adults. The entire project was approved by the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sport, Baden-Württemberg, under No. 31-6499.20/1235.

3.1. Participants

Several background variables were collected as part of the questionnaire (see Table 1). They reveal that at University A, approximately two-thirds of the respondents were female, and two-thirds studied language-related subjects, such as German, Spanish, or English, while the remaining third were enrolled in non-language-related subjects, such as Mathematics, Biology, Political Science, etc. At University B, only pre-service teachers preparing to become German teachers participated. All of them attended an obligatory university lecture on German as second language (GSL) and language-sensitive teaching.

Table 1.

Participants’ backgrounds.

Participants at both universities were at various stages of their studies, ranging from being in the first to their 13th semester. A typical teacher education program in Germany for secondary schools takes a minimum of nine semesters; however, it can be extended by several semesters individually.

3.2. The Questionnaire

The paper-and-pencil questionnaire included questions about participants’ demographics (age, gender, subjects studied (language subjects/non-language subjects), as well as the number of semesters studied), as seen above.

It further asked several questions related to their perceived preparedness for a linguistically diverse classroom and the role of teachers in fostering the language competences of students (this portion was only available to students at University A).

Concretely, the following questions were asked:

- (1)

- How well prepared do you feel to work with students that have grown up speaking another language besides German (to be indicated on a scale of 1–5, with 5 being the most prepared)?

- (2)

- Do you think that the language background of your students is relevant for your subjects (yes/no, for all subjects, specific to subjects)?

- (3)

- In your view, who should foster students with low German skills (German teachers, all teachers, external GSL teachers, other)?

Apart from the items above, eight additional items were taken from another survey (with the permission of the authors, Pulinx et al., 2017) to measure pre-service beliefs. These have been used in previous research conducted in Belgium, as well as in Greece, Italy, and the Netherlands (Pulinx et al., 2017; Bosch et al., 2024), and were adapted to German (translated items can be found in Table 2).

Table 2.

Eight items measuring teachers’ beliefs used in the questionnaire (adapted to German from Pulinx et al., 2017; English translation).

3.3. Analysis

After data collection, data was entered into SPSS and statistically analyzed using SPSS 29.0.

In order to calculate the “monolingual—multilingual index”, as we will name it henceforth, the procedure used by Pulinx et al. (2017) was employed. Items 1, 2, 5, 7, and 8 were calculated on a scale of 1–5 (including 0.5 steps), with 5 denoting strong agreement to monolingual beliefs, whereas the scale was reversed when coding Items 3, 4, and 6, where 5 denoted positive agreement toward multilingual beliefs. The sum of the items was then divided by eight.

4. Results

4.1. Perceived Preparedness for a Heterogeneous Classroom

A total of 23.1% of the pre-service teachers indicated that they felt prepared or well-prepared to deal with linguistic diversity in the classroom. There was no significant difference between pre-service teachers studying language subjects or non-language subjects (on a scale where 5 = being the most prepared: M = 2.94 (SD 0.94) (language subjects) vs. M = 2.93 (SD 0.85) (non-language subjects); t(115) = 0.056; p < 0.955)). Also, gender did not affect the results (male: M = 2.949, SD 0.156, female: M = 2.93; SD 0.889; t(115) = 0.107, p < 0.915). There was no significant correlation (r = 0.068; p < 0.467) between the number of semesters studied and the feeling of preparedness for the multilingual classroom. Yet, pre-service teachers with a higher number of semesters (7–13 semesters; n = 44) felt slightly better prepared (M = 3.03 (SD 0.95)) than pre-service teachers with a lower number of semesters ((1–6 semesters; n = 61) M = 2.869 (SD 0.879)).

While the multilingual pre-service teacher group was small, the difference between the preparedness of facing a heterogenous classroom was very evident. The difference between the mean values M = 4.042 (SD 0.456) (multilingual) and M = 2.810 (SD 0.853) (monolingual) was significant (χ2(1) = 23.279, p < 0.001).

A total of 50% of all the pre-service teachers thought that the linguistic background of the students matters in all subjects, 8.5% thought it does not matter, and the rest indicated that it depended on the subject. When asked specifically in which subject areas the heritage language of the students should matter, the responses were clearly differentiated (on a scale 1–5): Language subjects M = 3.5 (SD 1.09), social sciences M = 2.89 (SD 1.01), natural sciences M = 2.26 (SD 0.094).

This finding was influenced by the number of semesters studied. The higher the number of semesters of the pre-service teachers, the lower the role of the language background of the (future) students was judged to be of relevance for the social and natural sciences. The results for pre-service teachers with up to six semesters are as follows: Language subjects M = 3.42 (SD 1.19), social sciences M = 2.91 (SD 1.071), and natural sciences M = 2.45 (SD 0.98). The results for pre-service teachers with over seven semesters are as follows: Language subjects M = 3.6 (SD 0.92), social sciences M = 2.84 (SD 0.98), and natural sciences M = 2.02 (SD 0.86). The difference between pre-service teachers with higher and lower numbers of semesters and their viewpoints on language in the natural sciences was significant (t(114) = −2.169; p < 0.032).

A total of 33.9% of participants thought that all teachers are responsible for supporting students with lower German skills, whereas 22.9% felt that it should be the responsibility of external GSL teachers. A total of 36.4% thought that it should be the responsibility of all teachers and external GSL teachers combined (as it is often actually the case in German schools). The remaining percentage thought it should be the responsibility of German teachers (3.4%) or others (not specified): 1.7%.

4.2. Items Related to Beliefs Toward Multilingualism

The eight items employed in the study by Pulinx et al. (2017) were analyzed. Agreement was defined as “agree or completely agree”, in line with the study by Pulinx et al. (2017). However, it must be noted that Cronbach’s alpha in this study was at 0.632; below the Cronbach’s alpha of 0.816 in Pulinx et al. (2017). In Table 3, the results from both universities can be found.

Table 3.

Results from Universities A and B reflecting teachers’ beliefs (adapted to German from Pulinx et al., 2017; English translation).

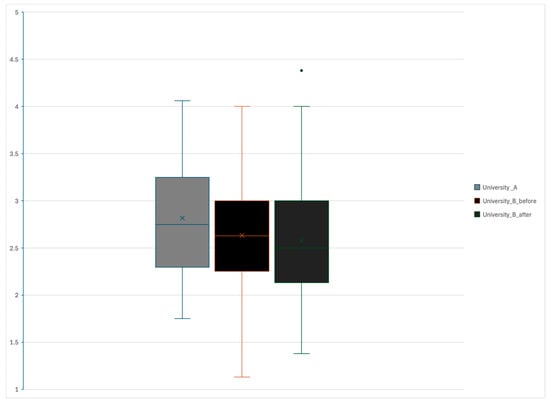

According to the procedure described above, at University A, the “monolingualism–multilingualism index” exhibited a mean of M = 2.91 (SD 0.96), and at University B, (before the lecture) the mean was M = 2.63 (SD 0.54). After the lecture at University B, the mean was M = 2.58 (SD 0.66). The lower the index (on a scale 1–5), the greater the multilingual beliefs. The results are visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mean values of the “monolingualism–multilingualism index” at University A and University B before and after the lecture (1 = most multilingual belief).

The three variables of language subject, monolingualism/multilingualism, and gender were entered into a regression model. While there were no significant influences of any of those variables at University A, at University B, the results of the model showed that female respondents at University B had significantly lower points on average, indicating more positive beliefs toward multilingualism compared to male respondents (R2Adjusted = 0.049; β = −0.301, p < 0.013). Similar results were found for multilingual respondents compared to monolingual respondents (β = −0.194, p < 0.044).

After the lecture, female respondents at University B showed only marginally more positive beliefs (R2Adjusted = 0.062; β = −0.336, p = 0.054), while multilingualism was a significant factor (β = −0.317, p < 0.033).

5. Discussion

The current study investigated three aspects that are relevant in addressing multilingual students’ needs in the linguistically diverse classroom: (a) pre-service teachers’ perceived preparedness for the classroom, (b) their beliefs towards multilingualism, and (c) the effects of a university lecture on GSL and language-sensitive teaching. A total of 267 pre-service teachers from two German universities participated in the study by completing a questionnaire that included an internationally recognized scale to assess beliefs about multilingualism.

- (a)

- Perceived preparedness for the heterogenous classroom

In earlier surveys conducted among teachers (Becker-Mrotzek et al., 2012) and pre-service teachers (Michalak, 2010) the preparedness for a linguistically diverse classroom was relatively low, at about one third (well-prepared or prepared), considering that virtually all teachers must teach students with multilingual backgrounds. A more recent study found that 55% of pre-service teachers felt prepared for the heterogenous classroom (Kaplan, 2023).

The current study found the preparedness of a sample of pre-service teachers studying language and non-language subjects to be even lower than that in the 2012-study of teachers, at 23.1%. While one must acknowledge that perhaps the “fear of the unknown” may be stronger in pre-service teachers studying at university compared to teachers already working at schools, this result contrasts with the more positive finding by Kaplan (2023) regarding pre-service teachers. In our study, preparedness was assessed on a scale of 1–5, while in Kaplan (2023), the results were assessed in an interview, thus potentially offering more nuanced viewpoints. In the study by Kaplan (2023), pre-service teachers were attending a GSL module at three different universities in Germany, while, at the time of the administration of the questionnaire, no such module was available at University A.

While one might expect that pre-service teachers in language subjects feel generally closer to linguistic heterogeneity by virtue of working with language acquisition and second language acquisition, this was not found in our study. Pre-service teachers at University A did not differ in their subjective preparedness whether they were studying language-related subjects or not. However, there was a difference between the multilingual pre-service teachers and the monolingual pre-service teachers, as has been found in previous studies, such as Hachfeld et al. (2012) and Schroedler and Fischer (2020).

Half of the pre-service teachers found that the language background of the students is relevant in all subjects, and a small percentage (8.5%) thought it did not matter at all. The remaining nearly 40% thought it depended on the subject. In a clearly differentiated way, language subjects were thought to need the most attention in terms of the linguistic background of the students, followed by the social sciences, and finally, the natural sciences. Interestingly, the further along pre-service teachers are in their studies, the more their attention appears to shift toward subject-specific content. This tendency is particularly evident for the natural sciences, where language-related aspects of teaching tend to be considered less relevant. In terms of language-sensitive teaching approaches (e.g., Gibbons, 2002), this suggests that awareness among pre-service teachers needs to be particularly strengthened in non-language disciplines, where linguistic aspects may otherwise be overlooked.

When questioned who should be responsible for addressing the language needs of students, 79% thought it should be all teachers; however, a subset thought that it should be teachers of all subjects and GSL teachers (37.3%), 82% and respectively 82.5% of the teachers in the studies by Becker-Mrotzek et al. (2012) and Kaplan (2023) felt responsible for addressing the language needs of students, so the total number here is comparable.

Overall, this portion of the study found a comparatively low subjective feeling of preparedness for the linguistically diverse classroom among pre-service teachers at these German universities. It is, however, positive and notable that pre-service teachers are aware that they themselves are responsible for fostering the language(s) and addressing the language needs of their students, rather than external persons. Yet, there still seems to be doubt among a considerable number of pre-service teachers that language is a relevant factor in all subjects—as evidenced by the finding that in the natural sciences, language may be less relevant than it is in the language subjects.

- (b)

- Beliefs toward multilingual students

Beliefs are a key precondition for effectively working with multilingual student populations. While some statements taken from Pulinx et al. (2017) in the questionnaire reflected multilingually oriented beliefs—such as offering books and media in different heritage languages (Statement 3) or offering to learn the heritage language at school (Statement 4)—there were still a lot of lingering monolingual beliefs among the participants. For instance, at University A, 14.1% of participants thought that students should be punished for using their heritage language at school (Statement 8); in the weaker version, 23.5% of participants thought that students should not be allowed to use their heritage language (Statement 1). At University B, agreement with Statement 1 was even higher (42.6%), which could denote a strong agreement with monolingual policies; however, looking at other statements, at University B overall, beliefs were slightly more multilingually oriented, e.g., only 1.4% of the participants thought that students should be punished for using their heritage language.

When calculating the means (M = 2.91 (SD 0.96) at University A and M = 2.63 (SD 0.54) at University B before the lecture), the two German groups of pre-service teachers can be placed between the teachers from Belgium (3.74 points (SD = 0.06; Pulinx et al., 2017)) and Greece (2.17; SD = 0.57) more in line with results from in Italy (2.62; SD = 0.64) and the Netherlands (2.62; SD = 0.69; Bosch et al., 2024). In Bosch et al. (2024), the authors reported that Greece has the strongest system for supporting teachers in their continuous training with respect to multilingualism. This is also due to Greece often being the first point of entry for migrants and refugees from countries such as Syria or Afghanistan.

While, in Belgium, secondary school teachers were investigated, and in Germany, individuals in pre-service training to become secondary school teachers were investigated, in Greece, Italy, and the Netherlands, primary school teachers were investigated. It has been reported that secondary school teachers might be less pedagogically oriented in terms of language support, whereas, in the lower classes, language acquisition in terms of reading/writing acquisition plays a larger role (Bosch et al., 2024).

The results reflect—to some degree—the persistence of what Gogolin (2008) has described as the “monolingual habitus”—a normative orientation toward monolingualism that continues to shape educational thinking and practice in contexts that are, in fact, multilingual.

Similar findings have been reported in other European countries, such as Norway. Vikøy and Haukås (2023), for instance, found that despite positive formulations about multilingualism in the national curriculum, Norwegian L1 teachers (n = 10) often adhered to a language-as-problem orientation, viewing minority students primarily through a deficit lens rather than recognizing their multilingual competencies as a resource. This suggests that the “monolingual habitus” is not limited to the German context but appears to be a broader phenomenon across national education systems in Europe.

These findings are further echoed in the United States. Gallagher and Scrivner’s (2024) recent systematic review revealed that teachers mainly expressed positive beliefs about multilingualism and heritage language maintenance. However, these positive beliefs were frequently accompanied by a lack of perceived responsibility for fostering students’ multilingualism in the classroom. At the same time, many teachers adhere to dominant language ideologies, particularly in their views on “nonstandard” varieties (e.g., Spanglish in the US), which were framed in deficit terms. The authors further reported that teachers frequently positioned multilingual students as lacking not only linguistic and academic proficiency but also cultural capital. Their families were often described as uninvolved, uneducated, or unreachable—perceptions that reinforce stereotypical deficit discourses and symbolically position multilingual students as “other” within educational institutions. This combination of positive views and structural detachment reflects the ambivalence and complexity of teacher beliefs and highlights the continued influence of monolingual norms in educational contexts.

Interestingly, none of the results at University A were affected by any of the variables that commonly influence beliefs: gender, multilingual background, or subjects (language vs. non-language subjects). We attribute this to the overall homogeneity of students at University A. It is a small university in a town in the south of Germany. Even though the Swiss border is very near, this is not as diverse an environment as some of the metropolitan areas in Germany would offer. In line with the results of Bosch et al. (2024), who found an effect of urban vs. rural areas (with rural areas showing less multilingually oriented beliefs), this might serve as an explanation.

However, at University B, the gender as well as the multilingualism of the participants played a role. There was certainly more multilingualism among the pre-service teachers there; also, language subjects typically attract more females, as can be seen by the higher proportion of female pre-service teachers in the sample from University B. While University B is also located in a university town comparable to the size of that of University A, the university is about three times larger, also attracting pre-service teachers from nearby metropolitan areas. In addition, there was no separate program for GSL at University A and no obligatory classes. At University B, however, at the (later) time of testing, an obligatory semester-long lecture (the one investigated here) had been already introduced. This may explain some of the apparent—albeit small—differences between University A and B.

- (c)

- The effects of a university-based lecture on GSL

The increase in average beliefs was relatively small (before, M = 2.63, and after, M = 2.58). The second analysis showed that the multilingual background well as to some extent the gender of the participants, had an impact on their beliefs, regardless of whether the values were measured before or after the lecture.

The limited increase in beliefs might be due to the fact that it was only one class in Baden-Württemberg instead of two (as in Berlin or North Rhine Westfalia). Another explanation could lie in the lecture format itself, which was less interactive than a seminar format and offered only a few opportunities for meaningful reflection and discussion. It became evident that a semester-long lecture is not sufficient to drastically shift the mind-set of pre-service teachers. This highlights the need to go beyond lecture-based formats and explore alternative, more practice-oriented models of teacher education. For instance, approaches in the Austrian context, which integrate case studies and interactive discussions, appear to be more fruitful (e.g., Bellet, 2020). The findings also underline a broader structural issue: despite considerable efforts from several universities, federal education policies in the state of Baden-Württemberg remain unchanged. In order to institutionalize multilingualism as a core element of teacher education, more systemic support is needed.

Limitations

The current study investigated pre-service teachers at one larger and one smaller university in southern Germany. Both universities only offer teacher training for secondary schools (i.e., not for elementary schools). Therefore, it remains to be seen how teachers from regular elementary schools might respond to those items (as in Bosch et al., 2024 or in Pohlmann-Rother et al., 2023).

Further limiting factors are as follows: The sample is not representative (convenient sample), as it only represents pre-service teachers from one federal state with its own federal policies and political make-up. This issue could be addressed by recruiting participants from across Germany. In addition, as a normal process, there is a loss of pre-service teachers throughout the semester. Also, the study relies on self-reported data, which is known to produce socially acceptable/desirable answers in surveys (Steiner & Benesch, 2018, p. 65). In this context, it is important to consider that teachers’ beliefs may not always be internally consistent or unambiguous. As Gallagher and Scrivner (2024) point out, teachers may simultaneously hold both positive and negative beliefs about multilingualism, which calls for the cautious interpretation of aggregate scores on belief scales. While this study addressed beliefs, the question of how those beliefs transform into actions when those pre-service teachers work in the classroom remains and needs to be considered in future studies. Further, due to organizational reasons, a paper-and-pencil test was chosen at the time, and not all subjects responded to the eight items from Pulinx et al. (2017). Another caveat is that Cronbach’s alpha was low - which may have been due to the questionnaire actually having been developed for in-service teachers, rather than pre-service teachers. Due to the anonymity of the questionnaire and time constraints, only group data could be analyzed and descriptively compared before and after the lecture. An actual pre-post design may have been able to shed further light on factors that influence potential changes. For further consideration, while the results of the “intervention” are not very strong, the first author of this paper may have subconsciously promoted some of the multilingual beliefs from the questionnaire.

6. Conclusions

The present study investigated pre-service secondary school teachers’ preparedness for the multilingual classroom, as well as their beliefs, at two universities in southern Germany. Overall, while the subjective feeling of preparedness is quite low, the awareness of the responsibility of fostering multilingual students is quite high. However, not all pre-service teachers assume that language is relevant for all school subjects (such as the natural sciences).

Compared to the two other studies conducted in Europe (Bosch et al., 2024; Pulinx et al., 2017), pre-service teachers’ beliefs are relatively multilingually oriented, even though some doubts and concerns from the perspectives for the multilingual classroom remain. It is apparent that multilingual pedagogies need to be introduced into all school subjects early on, as many teachers do not necessarily see the use of the heritage language as a positive and useful resource in the classroom. Overall, the curricular possibilities of fostering multilingualism in the classroom (multilingual pedagogies) must be addressed more consistently.

There is currently no shortage in concepts and methods, as well as research projects, but they have not yet reached classroom practice (Lundberg, 2019b). Further studies must follow pre-service teachers from university education into the classroom to reliably assess the changes required within university education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.R. and E.E.; methodology, TR. and E.E. formal analysis, T.R. and E.E., investigation, E.E. resources, T.R.; data curation, E.E.; writing—original draft preparation, T.R. and E.E. writing—review and editing, T.R. and E.E.; supervision, T.R. funding acquisition, T.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sport, Baden-Württemberg under No. 2 43-04HV.1403-98(20)/40/1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This project was approved by the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sport, Baden-Württemberg under No. 31-6499.20/1235.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Consent was given by filling out the questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be found under this link: https://osf.io/cp9am/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participating pre-service teachers. Also, we would like to acknowledge Kaja Gregorc, as well as Dilan Kurucu, for their help with data collection and data entry.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to publish the results.

References

- Alisaari, J., Heikkola, L. M., Commins, N., & Acquah, E. O. (2019). Monolingual ideologies confronting multilingual realities. Finnish teachers’ beliefs about linguistic diversity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 80, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, N., & Lahmann, C. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism in school: An evaluation of a course concept for introducing linguistically responsive teaching. Language Awareness, 29, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden-Württemberg Statistical Office. (2023). Available online: https://www.statistik-bw.de/BevoelkGebiet/MigrNation/010352xx.tab?R=LA (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Baumert, J., & Kunter, M. (2011). Das Kompetenzmodell von COACTIV [The competence model of COACTIV]. In M. Kunter, J. Baumert, W. Blum, U. Klusmann, S. Krauss, & M. Neubrand (Eds.), Professionelle Kompetenz von Lehrkräften—Ergebnisse des Forschungsprogramms COACTIV [Teachers’ professional competence—Findings from the COACTIV research program] (pp. 29–53). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Becker-Mrotzek, M., Hentschel, B., Hippmann, K., & Linnemann, M. (2012). Sprachförderung in deutschen Schulen—Die Sicht der Lehrerinnen und Lehrer. Ergebnisse einer Umfrage unter Lehrerinnen und Lehrern [Language support at German schools—The teachers’ view. Results of a survey among teachers]. Universität zu Köln: Mercator-Institut für Sprachförderung und Deutsch als Zweitsprache. [Google Scholar]

- Bellet, S. (2020). Gesamtsprachliche Bildung und früher Englischunterricht-Professionalisierung von Lehramtsstudierenden im Kontext von Mehrsprachigkeit. [Academic education and early language teaching—Professionalization of pre-service teachers in the context of multilingualism]. Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, K. A., Kilinc, S., Deeg, M. T., Marley, S. C., Farrand, K. M., & Kelley, M. F. (2021). Language ideologies of Arizona preschool teachers implementing dual language teaching for the first time: Pro-multilingual beliefs, practical concerns. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(4), 457–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, S., Maak, D., Ricart Brede, J., & Vetterlein, A. (2019). Kultur der Mehrsprachigkeit und monolingualer Habitus—Zwei Seiten einer Medaille? [Multilingual culture and monolingual habitus—Two sides of the same coin?]. In D. Maak, & J. Ricart Brede (Eds.), Wissen, Können, Wollen—Sollen?! Angehende LehrerInnen und äußere Mehrsprachigkeit [Knowing, being able, wanting—Should? Pre-service teachers and external multilingualism] (pp. 29–38). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, J. E., Olioumtsevits, K., Santarelli, S. A. A., Faloppa, F., Foppolo, F., & Papadopoulou, D. (2024). How do teachers view multilingualism in education? Evidence from Greece, Italy and The Netherlands. Journal of Language and Education, 39, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- bpb (Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung (German Office for Political Education)). (2023). Available online: https://www.bpb.de/kurz-knapp/zahlen-und-fakten/soziale-situation-in-deutschland/61646/bevoelkerung-mit-migrationshintergrund/ (accessed on 17 September 2023).

- Calafato, R. (2020). Language teacher multilingualism in Norway and Russia: Identity and beliefs. European Journal of Education, 55, 602–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohrmann, J. (2021). Überzeugungen von Lehrkräften: Ihre Bedeutung für das pädagogische Handeln und die Lernergebnisse in den Fächern Englisch und Mathematik [Teachers’ beliefs: Their significance for educational action and learning outcomes in English and Mathematics]. Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Education Report. (2024). Education in Germany. Available online: https://www.bildungsbericht.de/de/bildungsberichte-seit-2006/bildungsbericht-2024/pdf-dateien-2024/bildungsbericht-2024.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Fischer, N. (2020). Überzeugungen angehender Lehrkräfte zu sprachlich-kultureller Heterogenität in Schule und Unterricht: Theoretische Struktur, empirische Operationalisierung und Untersuchung der Veränderbarkeit [Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural heterogeneity in school and teaching: Theoretical structure, empirical operationalization and examination of changeability] [Ph.D. Dissertation, Leuphana Universität Lüneburg]. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, N., & Ehmke, T. (2019). Empirische Erfassung eines “messy constructs”: Überzeugungen angehender Lehrkräfte zu sprachlich-kultureller Heterogenität in Schule und Unterricht [The empirical analysis of a “messy construct”: Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural heterogeneity in school and teaching]. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 22(2), 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons-Doolan, S. (2014). Language ideologies of Arizona voters, language managers, and teachers. Journal of Language Identity and Education, 13(1), 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons-Doolan, S., Palmer, D. K., & Henderson, K. (2017). Educator language ideologies and a top-down dual language program. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 20(6), 704–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, B. B., & Smith, H. L. (2009). Teachers’ characteristics and attitudinal beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity. Bilingual Research Journal, 31(1–2), 323–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M. A., & Scrivner, S. (2024). Teachers’ beliefs about language diversity and multilingual learners: A Systematic review of the literature. Review of Educational Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, P. (2002). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning: Teaching second language learners in the mainstream classroom. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Gogolin, I. (1997). The “monolingual habitus” as the common feature in teaching in the language of the majority in different countries. Per Linguam, 13(2), 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogolin, I. (2008). Der monolinguale Habitus der multilingualen Schule [The monolingual habitus of the multilingual school]. Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Hachfeld, A., Schroeder, S., Anders, Y., Hahn, A., & Kunter, M. (2012). Multikulturelle Überzeugungen [Multicultural beliefs]. Zeitschrift Für Pädagogische Psychologie, 26(2), 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, S., Fischer, N., & Koch-Priewe, B. (2016). Überzeugungen von Lehramtsstudierenden zu Mehrsprachigkeit in der Schule [Pre-service teachers’ beliefs on multilingualism in school]. In B. Koch-Priewe, & M. Krüger-Potratz (Eds.), Die Deutsche Schule—Beiheft 13 (pp. 147–171). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, I. (2023). Einstellungen von Lehramtsstudierenden zu sprachlich-kultureller Vielfalt in der Schule. Eine qualitative Studie. [Pre-service teachers’ beliefs on linguistic and cultural diversity in schools—A qualitative study]. Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (2013). Preparing linguistically responsive teachers: Laying the foundation in preservice teacher education. Theory Into Practice, 52(2), 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, T., Villegas, A. M., & Martin, A. (2015). Teachers’ beliefs about English language learners and their education. In H. Fives, & M. G. Gill (Eds.), International handbook of research on teachers’ beliefs (pp. 453–474). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, A. (2019a). Teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism: Findings from Q method research. Current Issues in Language Planning, 20(3), 266–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, A. (2019b). Teachers’ viewpoints about an educational reform concerning multilingualism in German-speaking Switzerland. Learning and Instruction, 64, 101244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, M. (2019). Accommodating linguistic prejudice? Examining English teachers’ language ideologies. English Teaching, 18(1), 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M. (2010). Sprachförderung—Ja, aber von wem? [Language support—Yes, but by whom?]. In C. Chlosta, & M. Jung (Eds.), DaF integriert: Literatur—Medien—Ausbildung. 36. Jahrestagung des Fachverbandes Deutsch als Fremdsprache 2008 an der Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf [Integrating DaF: Literature—Media—Teacher Education. Proceedings of the 36th Annual Conference of the German Association for German as a Foreign Language (FaDaF) at Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf] (pp. 229–244). Universitätsverlag Göttingen. [Google Scholar]

- Morris-Lange, S., Wagner, K., & Altinay, L. (2016). Lehrerbildung in der Einwanderungsgesellschaft: Qualifizierung für den Normalfall Vielfalt [Teacher education in the migration society: Preparing for diversity as the norm]. SVR-Forschungsbereich. [Google Scholar]

- Paetsch, J., Heppt, B., & Meyer, J. (2023). Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about linguistic and cultural diversity in schools: The role of opportunities to learn during university teacher training. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlmann-Rother, S., Lange, S. D., Zapfe, L., & Then, D. (2023). Supportive primary teacher beliefs towards multilingualism through teacher training and professional practice. Journal of Language and Education, 37(2), 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulinx, R., van Avermaet, P., & Agirdag, O. (2017). Silencing linguistic diversity: The extent, the determinants and consequences of the monolingual beliefs of Flemish teachers. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 20(5), 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reusser, K., & Pauli, C. (2014). Berufsbezogene Überzeugungen von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern [Teachers’ professional beliefs]. In E. Terhart, H. Bennewitz, & M. Rothland (Eds.), Handbuch der Forschung zum Lehrerberuf [Handbook of research on the teaching profession] (pp. 642–661). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Schroedler, T., & Fischer, N. (2020). The role of beliefs in teacher professionalisation for multilingual classroom settings. European Journal of Applied Linguistics, 8(1), 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroedler, T., Rosner-Blumenthal, H., & Böning, C. (2023). A mixed-methods approach to analysing interdependencies and predictors of pre-service teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism. International Journal of Multilingualism, 20(1), 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, E., & Benesch, M. (2018). Der Fragebogen—Von der Forschungsidee zur SPSS-Auswertung. [The questionnaire—From research idea to SPSS analysis]. Facultas. [Google Scholar]

- Vikøy, A., & Haukås, A. (2023). Norwegian L1 teachers’ beliefs about a multilingual approach in increasingly diverse classrooms. International Journal of Multilingualism, 20(3), 912–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, A. (2017). Sprachbildung in der Lehrerausbildung [Language education in pre-service teacher education]. In M. Becker-Mrotzek, & H. Roth (Eds.), Sprachliche Bildung—Grundlagen und Handlungsfelder [Language education—Basics and fields of action] (pp. 351–364). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).