Methodology Based on Critical Reflective Dialogue to Optimize Educational Leadership

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Educational Leadership Practices

1.2. Potentials of Critical Reflective Dialogue to Optimize Educational Leadership

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Approach

2.2. Variable

2.3. Population, Sample and Sampling

2.4. Instruments Used to Obtain Information

2.5. Fieldwork

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Phase

- Analysis of the results for each domain

3.2. Qualitative Phase

- Address Configuration

“Parents do not identify with the institution, they believe that everything must be given to the students, it is complicated, meetings are called and the grandmother, an older brother and even a neighbor attend”.(DR_x)

“With the pandemic, instead of improving, things have gotten worse. Students don’t like to read, they’re told to stop looking at their cell phones, even though they’re forbidden from bringing them to school”.(DR_r)

Some teachers try hard, but if a child doesn’t want to study, what can they say? Even parents support their bad behavior; during harvest time, there’s a lot of absenteeism.(DR_v)

“The area coordinator gives me a document with the program that we have to carry out during the year”.(D2)

“Parents are called to submit student reports, and only some attend, others wait until the end of the year”.(D4)

- Building relationships and personal development

I don’t always go to class. Besides, I don’t need to stay the whole hour, since we know who’s working (…) if the contracted teachers have any questions, they have an hour of class time for that.(DR_t)

Teachers apply for a contract each year; of the 100%, 10% return, while others migrate to a new institution. Therefore, the coordinators provide them with everything they need to work during the school year.(DR_p)

“The schedule is from 7:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. Each teacher works 32 h and leaves school. They don’t stay if they’re called to a meeting. Contract teachers finish at 1:00 p.m. because it’s convenient for them”.(DR_w)

“Unfortunately, parents no longer care about their older children, and it is during adolescence that they have to be more careful with who they associate with, which is why there are problems in the institution”.(DR_x)

“The meetings we have had with the leader are for some activities such as the school anniversary, for other activities we have working committees”.(D5)

“Through collegial meetings, we share the schedules that correspond to the next unit”.(D3)

- Design the organization for the desired practices.

“Sometimes we have virtual meetings, but you don’t know if they’re listening because they don’t turn on their cameras, and you have to call them several times.”(DR_y)

“They have become accustomed to the virtual world, but they do not participate, they say they do not have a good connection, that problem has been brought about by virtuality”.(DR_p)

“This is the largest and most recognized school, but the classrooms are at risk, the (tin) roof is in poor condition in three classrooms, it is going to rain and the students will not be able to use them”.(DR_x)

“As a teacher, I want my students to learn, but there is no greater support from parents”.(D3)

“They are another generation, now you can’t even yell at the students because they report you”.(D5)

“At school we divide the sessions that each one is going to develop… since they are the same topics, first they sent me one as a model and from there I guide myself”,(D8)

- Improve instructional programs

“We are very low in learning outcomes; students must also do their part”.(DR_r)

“We have reading and writing deficiencies, they (students) do not participate (students) in class in the presentations, the teacher tells who can participate and they remain silent; what can we do if the parents do not support either”.(DR_x)

“We support each other in programming with our classmates, each one does a unit that we share each month”.(D3)

“To program we follow the pedagogical processes, we start from previous knowledge, we look for something that catches their attention, but it is difficult with young people, they have a different mentality”,(D5)

- Ensure accountability

“(…) the notebooks are delivered punctually, the coordinators organize themselves to collect the records”.(DR_w)

“(…) we have a problem with student performance, we have seen the need at the end of the first two months to rethink learning”,(DR_v)

“We are all responsible: parents, teachers, and students; but if parents don’t support us, they take away our authority, how can I move forward?”.(D4)

“The leader is informed of the students’ progress, but the responsibility always falls on the teacher; not all of one’s effort is recognized”.(D7)

“(…) It’s not until the end of the year that parents find out whether a student passed or failed. Some are illiterate; they only look at the blue color of the notebook, and that’s enough for them”.(D6)

“(…) the villagers here no longer have expectations; they know that he will be a motorcycle taxi driver or that he will work in the fields like his father”.(D8)

4. Discussion

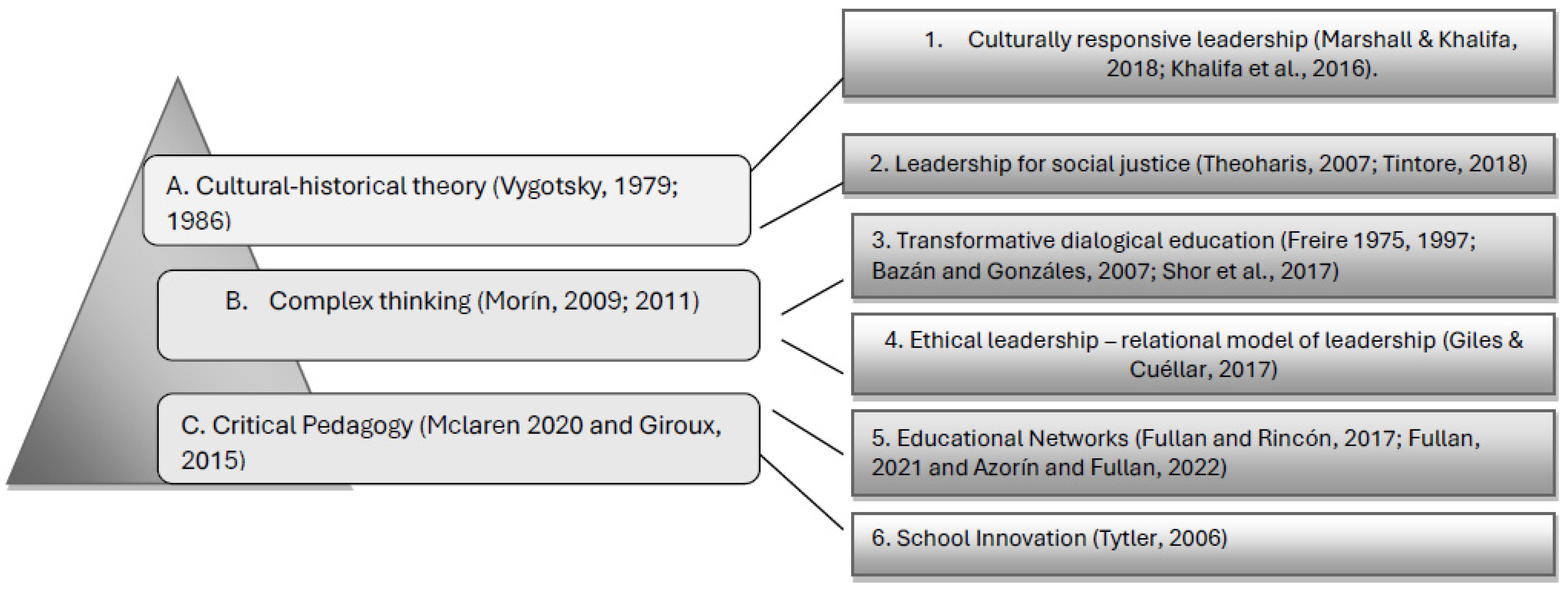

4.1. Proposed Theoretical Framework for the Formation of Educational Leadership Practices

Conceptual Phase

4.2. Projective Phase

4.3. Transformation Phase

4.4. The Phase of Epistemic Transcendence

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antúnez, S., & Silva, P. (2020). The training of school principals and educational inspection. Advances in Educational Supervision, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyropoulou, E., & Lintzerakou, E. E. (2025). Contextual factors and their impact on ethical leadership in educational settings. Administrative Sciences, 15(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azorín, C., & Fullan, M. (2022). Leading new and deeper forms of collaborative cultures: Questions and paths. Journal of Educational, 23, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, B. (1999). Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(1), 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazán, D., & González, L. (2007). Autonomía profesional y reflexión del docente: Una resignificación. REXE. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Beycioğlu, K., & Kondakci, Y. (2021). Organizational change in schools. ECNU Review of Education, 4(4), 788–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, M., James, C., & Fertig, M. (2017). The difference between educational management and educational leadership and the importance of educational accountability. Educational Management, Administration, and Leadership, 47(4), 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, R. (2019). Being a school principal: A different professional identity? International seminar: Teaching profession and continuing education in Latin America: Lessons and challenges. Center for the Study and Development of Continuing Teacher Education, University of Chile. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Galindo, P., Rodríguez-Santero, J., & Torres-Gordillo, J.-J. (2021). Improvements in guided practices based on a systematic review of studies on school effectiveness. REOP—Spanish Journal of Guidance and Psychopedagogy, 32(3), 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deroncele-Acosta, A., Brito-Garcías, J. G., Sánchez-Trujillo, M. A., Delgado-Nery, Y. M., & Medina-Zuta, P. (2023). Theoretical-practical modeling method in social sciences. University and Society, 15(3), 366–384. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, M., Ruiz, A., Medina, M., Loor, M., Pérez, E., & Medina, A. (2020). Teacher training in intercultural dialogue and understanding: A focus on education for sustainability. Sustainability, 12, 9934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, L. (2008). Reflections on ‘reflective practice’. In Practice-based professional learning (Paper 52). The Open University. [Google Scholar]

- Forde, C., Torrance, D., & Angelle, P. S. (2021). Caring practices and social justice leadership: Case studies of school principals in Scotland and the U.S. School Leadership & Management, 41(3), 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. (1975). Education for social change. Tierra Nueva. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (1997). Pedagogy of autonomy: Knowledge necessary for educational practices. Tierra Nueva. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. (2021). The New meaning of educational change. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M., & Rincón-Gallardo, S. (2017). California’s golden opportunity. In Taking stock: Leadership from the middle. Motion Leadership. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, D., & Cuéllar, C. (2017). Ethical leadership: A moral way of being in leadership. In Educational leadership in schools: Nine perspectives. Center for Educational Leadership Development (Cedle). [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H. (2015). Democracy, higher education, and the specter of authoritarianism. Education and Society, 2, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gümüş, S., Arar, K., & Oplatka, I. (2020). A review of international research on school leadership for social justice, equity, and diversity. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 53(1), 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M., & James, C. (2017). Developing a perspective on schools as complex, evolving, and loosely coupled systems. Educational Management, Administration, and Leadership, 46(5), 729–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, N., & Kaur, S. (2024). Power and pedagogical failure: In search of a politics of empathy towards an anti-racist academy. Journal of International Political Theory, 20(3), 309–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Sampieri, R., & Mendoza, C. (2018). Research methodology: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. McGraw Hill Education. ISBN 978-1-4562-6096-5. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, S. G., & Pruitt, J. (2024). Transforming educational leadership through multiple approaches to school leadership development and support. Educational Sciences, 14(9), 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturra, C., & Cansino, E. (2018). Advising educational management and leadership teams. Since then, the functional competencies approach. Ensaio: Avaliação e Políticas Públicas em Educação, Rio de Janeiro, 26(101), 1220–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, C., Connolly, M., & Hawkins, M. (2020). Reconceptualizing and redefining the practice of educational leadership. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 23(5), 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N. (2023). Leadership in action: An introspective reflection. In D. Roache (Ed.), Transformational leadership styles, management strategies, and communication for global leaders (pp. 43–57). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, M., Gooden, M., & Davis, J. (2016). Culturally responsive school leadership: A literature synthesis. Journal of Educational Research, 86(4), 1272–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, N. (2019). Segregation by socioeconomic status as a dimension of educational exclusion: 15 years of evolution in Latin America. Archivos Análisis de Políticas Educativas, 27, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, V., & Loeb, S. (2000). Chicago elementary school size: Effects on teacher attitudes and student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 37, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K. (2021). A review of the evidence on equitable school leadership. Educational Sciences, 11, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K. (2023). The personal resources of successful leaders: A narrative review. Educational Sciences, 13, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S., & Khalifa, M. (2018). Humanizing school communities. Culturally responsive leadership in shaping curriculum and instruction. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(5), 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, E., García, I., & Higueras, M. (2018). Leadership for school improvement and social justice. A case study of a compulsory secondary education center. REICE. Ibero-American Journal of Quality, Effectiveness and Change in Education, 16(1), 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, P. (2020). The Future of critical pedagogy. Philosophy and Theory of Education, 52(12), 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morín, E. (2009). Introduction to complex thinking. GEDISA Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Morín, E. (2011). The path to the future of humanity. Paidós, State and Society. [Google Scholar]

- Murillo, F. J., & Martínez-Garrido, C. (2017). Estimating the magnitude of school segregation in Latin America. Magis, International Journal of Research in Education, 9(19), 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niesche, R. (2024). Culturally responsive leadership: A case study of improving relationships between indigenous communities and schools. In Various (Ed.), Schooling for Social justice, equity, and inclusion: Problematizing theory, policy, and practice (pp. 95–118). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashiardis, P., & Johansson, O. (2020). Successful and effective schools: Bridging the gap. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(5), 690–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pring, R. (2014). Leadership: Competent manager or virtuous practitioner? Investing in our education: Leadership, learning, research and the doctorate (Vol. 13, pp. 59–73). International Perspectives on Higher Education Research. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, O., Vivas, A., Mota, K., & Quiñónez, J. (2020). Transformational leadership from a pedagogical perspective. Sophia, Philosophy of Education Collection, 28(1), 237–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C. (2021). Principal leadership in schools that overcome contextual barriers. REICE. Ibero-American Journal of Quality, Effectiveness and Change in Education, 19(1), 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkr, M., & O’Sullivan, J. (2022). Dialogical conceptualizations of leadership in a social enterprise. Early Years, 43(4), 938–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D. (1998). The reflective professional. How professionals think when they act. Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- SENAMHI (National Meteorological and Hydrological Service of Peru). (2021). Climate scenarios: Changes in climate extremes in Peru by 2050. Available online: https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/1310725/Interviews-ClimateChangeScenarios%20%281%29.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Shor, I., Matusov, E., Marajanovic, S., & Cressell, J. (2017). Dialogic and critical pedagogies: An interview with ira shor. Dialogic Pedagogy: An International Online Journal, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E., & Gumus, S. (2022). Socioeconomic achievement gaps and the role of school leadership: Addressing inequality in student achievement within and between schools. International Journal of Educational Research, 112, 101951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharis, J. (2007). Social justice educational leaders and resilience: Toward a theory of social justice leadership. Educational Administration Quarterly, 43(2), 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tintoré, M. (2018). Leaders in education and social justice. A comparative study. Pontifical Catholic University of Valparaíso. Educational perspective. Teacher Training, 57(2), 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tytler, R. (2006). School-based innovation in science: A model for supporting school and teacher development. Research in Science Education, 37, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassallo, B. (2021). Leading the flock: Examining the characteristics of multicultural school leaders in their pursuit of equitable education. Improving Schools, 25(1), 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigo-Arrazola, B., & Beach, D. (2020). Promoting professional development to build a socially just school through participation in ethnographic research. Professional Development in Education, 47(1), 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volosnikova, L., Fedina, L., & Bruk, Z. (2024). Leadership positions: Principals of inclusive schools: Foreign discourse. Social Psychology and Society, 15(1), 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1979). El desarrollo de los procesos psicológicos superiores. Grijalbo. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1986). Thought and language. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. (2018). Pulling at your heartstrings: Examining four leadership approaches from the neuroscience perspective. Educational Administration Quarterly, 55(2), 328–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, J., Cuellar, C., Hernández, M., & Flessa, J. (2016). Innovative experiences and renewal of Latin American management training. Journal of Education, 69, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2023). Growing strong: A poverty and equity assessment for Peru. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099042523145533834/pdf/P17673806236d70120a8920886c1651ceea.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Young, M. D., Anderson, E., & Nash, A. M. (2017). Preparing school leaders: Standards-based curriculum in the United States. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 16(2), 228–271. [Google Scholar]

- Zeichner, K. (1993, ). The teacher as a reflective professional. Conference presented at the 11th University of Wisconsin Reading Symposium. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/handle/20.500.12365/18007 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Zhang, J., Huang, Q., & Xu, J. (2022). Relationships among transformational leadership, professional learning communities, and teacher job satisfaction in China: What do principals think? Sustainability, 14(4), 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Domains | Specific Practices |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Address Configuration | Build a shared vision; identify specific, shared, and time-bound goals; create high performance expectations; communicate the vision and goals; create a shared, time-bound vision; and communicate the vision and goals. |

| 2 | Building relationships and developing people. | Stimulate the growth of the capacities of the staff professionals; provide support and demonstrate consideration of the members’ individual characters, as well as model the values and practices of the school, congruent relationships of trust with and between staff, students, and parents. Establish labor relations productive with representatives of the teachers’ federation. |

| 3 | Design the organization to support desired practices | Build cultures of collaboration and shared leadership; structure the organization to facilitate collaboration; build productive relationships with families and communities; connect the school to its broader environment; maintain a safe and healthy school environment; and allocate resources to support the school’s vision and goals. |

| 4 | Improve instructional programs | Staff the instructional program; provide instructional support; monitor student learning and progress toward school improvement; protect staff from distractions while on the job; and interact with teachers in their professional learning activities. |

| 5 | Ensure accountability | Promote a sense of internal staff accountability and address demands for external accountability. |

| Leaders | Teachers | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Informant | Gender | Duration of Office | No. | Informant | Gender | Condition |

| 1 | DR_x | male | 5 years | 1 | D1 | male | appointed |

| 2 | DR_v | male | 2 years | 2 | D2 | male | appointed |

| 3 | DR_z | male | 3 years | 3 | D3 | female | appointed |

| 4 | DR_r | male | 1 year | 4 | D4 | male | appointed |

| 5 | DR_t | female | 3 years | 5 | D5 | male | contracted |

| 6 | DR_p | male | 2 years | 6 | D6 | male | appointed |

| 7 | DR_w | male | 3 years | 7 | D7 | female | appointed |

| 8 | DR_y | male | 2 years | 8 | D8 | male | contracted |

| Rating Scale | Never | Hardly Ever | Sometimes | Almost Always | Always | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Items | F | % | F | % | F | % | F | % | F | % |

| Address Configuration |

| 1 | 0.7 | 6 | 4.4 | 58 | 42.6 | 64 | 47.1 | 7 | 5.1 |

| 2 | 1.5 | 5 | 3.7 | 46 | 33.8 | 51 | 37.5 | 32 | 23.5 | |

| 1 | 0.7 | 3 | 2.2 | 26 | 19.1 | 63 | 46.3 | 43 | 31.6 | |

| 4 | 2.9 | 9 | 6.6 | 25 | 18.4 | 44 | 32.4 | 54 | 39.7 | |

| Building relationships and personal development |

| 1 | 0.7 | 12 | 8.8 | 60 | 44.1 | 56 | 41.2 | 7 | 5.1 |

| 4 | 2.9 | 20 | 14.7 | 62 | 45.6 | 34 | 25 | 16 | 11.8 | |

| 2 | 1.5 | 2 | 1.5 | 22 | 16.2 | 72 | 52.9 | 38 | 27.9 | |

| 1 | 0.7 | 9 | 6.6 | 45 | 33.1 | 52 | 38.2 | 29 | 21.3 | |

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.5 | 26 | 19.1 | 72 | 52.9 | 36 | 26.5 | |

| Design the organization to support desired practices |

| 1 | 0.7 | 8 | 5.9 | 22 | 16.2 | 49 | 36 | 56 | 41.2 |

| 3 | 2.2 | 10 | 7.4 | 54 | 39.7 | 57 | 41.9 | 12 | 8.8 | |

| 0 | 0 | 8 | 5.9 | 44 | 32.4 | 52 | 38.2 | 32 | 23.5 | |

| 4 | 2.9 | 6 | 4.4 | 35 | 25.7 | 39 | 28.7 | 52 | 38.2 | |

| 0 | 0 | 5 | 3.7 | 12 | 8.8 | 52 | 38.2 | 67 | 49.3 | |

| 0 | 0 | 4 | 2.9 | 9 | 6.6 | 39 | 28.7 | 84 | 61.8 | |

| Improve instructional programs |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 13.2 | 71 | 52.2 | 47 | 34.6 |

| 3 | 2.2 | 14 | 10.3 | 60 | 44.1 | 47 | 34.6 | 12 | 8.8 | |

| 0 | 0 | 4 | 2.9 | 10 | 7.4 | 51 | 37.5 | 71 | 52.2 | |

| 0 | 0 | 9 | 6.6 | 21 | 15.4 | 69 | 50.7 | 37 | 27.2 | |

| 1 | 0.7 | 12 | 8.8 | 47 | 34.6 | 50 | 36.8 | 26 | 19.1 | |

| Ensure accountability |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 15.4 | 38 | 27.9 | 77 | 56.6 |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.7 | 13 | 9.6 | 42 | 30.9 | 80 | 58.8 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gamarra-Mendoza, S.; Brito-Garcías, J.G. Methodology Based on Critical Reflective Dialogue to Optimize Educational Leadership. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060776

Gamarra-Mendoza S, Brito-Garcías JG. Methodology Based on Critical Reflective Dialogue to Optimize Educational Leadership. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):776. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060776

Chicago/Turabian StyleGamarra-Mendoza, Sofía, and José Gregorio Brito-Garcías. 2025. "Methodology Based on Critical Reflective Dialogue to Optimize Educational Leadership" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060776

APA StyleGamarra-Mendoza, S., & Brito-Garcías, J. G. (2025). Methodology Based on Critical Reflective Dialogue to Optimize Educational Leadership. Education Sciences, 15(6), 776. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060776