Discourse Within the Interactional Space of Literacy Coaching

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How did the coach and teacher define a successful coaching relationship?

- (2)

- How did the coach and teacher position themselves, each other, and the coaching context within the conversations?

- (3)

- How did the positionings of the coach and teacher manifest within the interactional space, and what characteristics define the nature of their talk during these interactions?

1.1. Review of the Literature

1.2. Theoretical Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Pre-Interviews

2.3.2. Coaching Cycles

2.3.3. Coach Think-Aloud Protocols

2.3.4. Post-Interviews

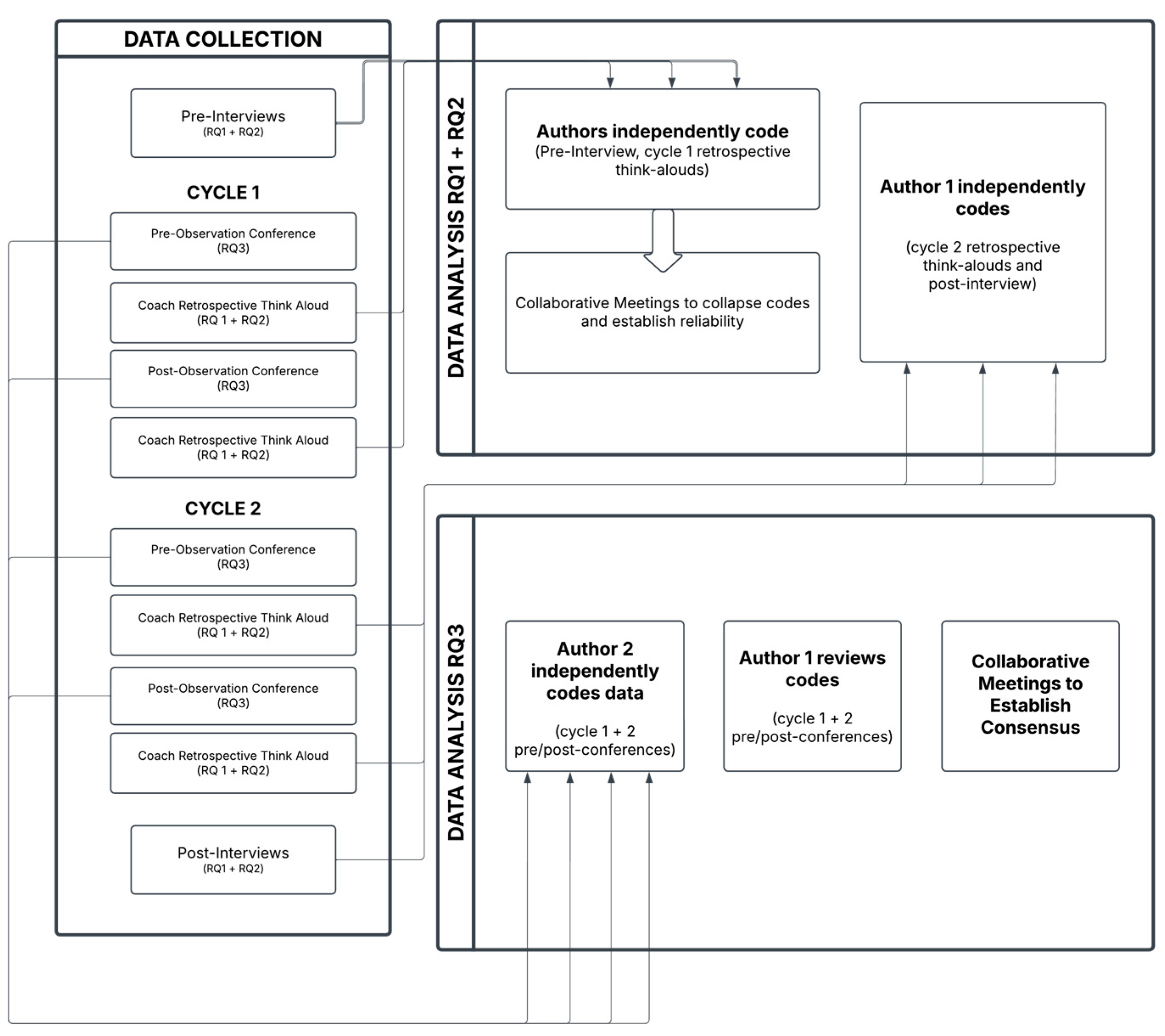

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Interviews

2.4.2. Coaching Cycle Meetings

2.4.3. Coach Retrospective Think-Aloud Protocols

2.4.4. Establishing Analytic Trustworthiness

3. Results

3.1. RQ1: How Did the Coach and Teacher Define a Successful Coaching Relationship?

3.1.1. Participation

It’s something that’s very mutually sought after for this coaching to happen. That she [Kathy] like enjoys coming in and getting to coach, and I enjoy someone who is willing to coach.(pre-interview, lines 160–162)

A lot of collaborative building—we did quite a lot of collaboratively building…recording sheets or ways to collect data or like ways to look at and think about certain aspects.(lines 53–63)

It was really positive and that it was really open—a very open collaboration, and we were able to just have some really good discussions about the learning and the teaching that the kids had.(lines 15–18)

It’s very flexible depending on what we’re doing…that something that’s different for me than some of the coaching I’ve had in the past, and I think it’s made the experience a lot more productive for me.(lines 137–139)

3.1.2. Connectedness

The respect and the trust between us is really important and probably the most important thing … I know that when she comes in and when she’s talking to me, it’s not from a judgmental standpoint.(post-interview, lines 69–75)

being really focused and knowing what I wanted to get out of the meetings…That is successful because you can let time get away, and if the teachers, I think, are feeling, well, this wasn’t really useful for me or this was a hindrance, they you’re not going to be to continue coaching”.(post-interview, lines 132–136)

We were able to meet and do some preplanning…with the vision and that specific focus of what we were working on. And so that was really helpful and beneficial.(post-interview, lines 17–22)

The more I work with her, the closer we get and the more comfortable we are and the more we learn about how the other person works. And so we can have just better and better conversations as we go”.(lines 41–43)

3.1.3. Knowledge Development

I’m not in here to correct something or do something… I don’t have the answers. So taking that stance as not being an expert, and I’ll say—look, I might have to look some of this stuff up or I’m not going to know everything.(lines 158–162)

I was right but just—so just let her come to that decision…It’s always, I think, about letting the teacher guide the conversation so that they can come—they’re the ones initiating the ideas and concepts.(retrospective think-aloud 3, lines 125–130)

If they have this great strategy but I don’t feel really comfortable with how that strategy is supposed to work or what the outcome is supposed to be, then that makes it hard for me to really take it on.(lines 107–108)

I think one of the things that helps me a lot is that I really like research, and I like to learn like new just actual, specific things that I can put into my toolkit and walk away with and try out.(lines 106–109)

3.1.4. Approach

I think that’s where I see it with Abby is just it might not be a direct conversation of a direct link, but I know because of what we say she puts that to other areas”.(lines 187–189)

“it should never be about the specific lesson”.(lines 193–194)

that focus when they [a coach] come in to coach has to be so specific. Otherwise, the feedback that I get is so broad that it—well, it usually does two things. Why they come in and they’re looking like at the whole lesson, for example, then I might either get super broad feedback like your timing should be better and your engagement should be better and your—or it gets so specific like, well, maybe you have asked this question instead of that question. Well, that doesn’t—that helps me on that lesson next year when I teach that specific lesson, but it doesn’t necessarily make me a better teacher.(pre-interview, Lines 75–82)

3.2. RQ2: How Did the Coach and Teacher Position Themselves, Each Other, and the Coaching Context Within the Conversations?

3.2.1. Positioning of Self

I’m not allowing enough space. I think that is how much I have to guide a new teacher in coaching and someone I haven’t worked with versus someone we have worked together.(lines 243–245)

I’m very glad I didn’t come in and—not that—I don’t think I would say this—but you did it great here, but you didn’t do it well here. Well, I’m not supposed to have that judgment.(lines 412–415)

I think it’s a nice… reminder you always want to stay in raw data, because when you go up your Ladder of Inference, it could be totally different than what you expected”.(lines 34–36)

…you have to be organized to keep it straight and be able to say, well, how will this data make sense? Because we’re the ones presenting the data and hopefully it is mostly raw data.(lines 75–80)

3.2.2. Positioning of One Another

It does not feel evaluative at all and just very—it’s very mirror oriented almost. She’s kind of like—gives me a chance to really look at my teaching more deeply. So a lot of what she does in her role is just helping me to clearly see what I’m doing so that I can reflect on it.(lines 42–45)

Just a lot of—have you thought about—and almost never directly enough for me to be able to say—figure out what she wants. Which I’m sure is part of her goal—so sometimes frustrating.(lines 49–51)

when they come in to coach has to be so specific. Otherwise, the feedback that I get is so broad that it…like your timing should be better and your engagement should be better”.(lines 75–78)

She’s very much involved in our day-to-day learning and teaching, and so the way that I mostly approach it is just being able to ask questions. Since she’s so involved in what we do every day, we can—she’s such a good resource.(lines 16–19)

She does very little teaching toward me of here’s what you should do and a lot of questioning about, so why did you do that? Is there another way? And providing the resources that I might need to learn and grow in certain areas as well.(lines 41–52)

…we do the framework of the HLPs (TeachingWorks, 2025) and it was interesting last year. So [Abby’s] relationship would be a continuation of last year. It was kind of what ones seem interesting to you, what is an area of your practice you want to get better at?”.(lines 77–81)

[Abby] references the HLP, because she likes studying them and working them. I think at one point I say that the HL—we don’t have to have the right name or the right number. That’s not—it’s just getting to the what she wants to learn with her practice is most important.(lines 86–89)

…you can see she does think a lot about her teaching and her instruction already. So a lot of [her coaching] is letting her get that out because she is an experienced teacher and what is she thinking about so then I know my next moves to take in the conversation”.(lines 65–69)

I would not have brought this conversation up with anyone else, probably, in the building—because they haven’t—they don’t have the experience. And she doesn’t have the in-depth experience that I know I’ve studied, but she at least knows the difference and knows what I’m talking about”.(retrospective think-aloud 3, lines 202–205)

…just knowing she is a very thoughtful person and a reflective person. So it wasn’t as much of me like…worrying where we would get to. We’re going to get to someplace good, and where that goes, that’s okay, and I’m okay with that.(lines 25–28)

… I gave her the space that she could think about that. And that’s what’s the most important thing, I think, about coaching is allow teachers to have the space to reflect on their practice without judgment.(lines 490–492)

3.2.3. Positioning of Context

So Abby references the HLP, because she likes studying them and working them. I think at one point I say that …we don’t have to have the right name or the right number…it’s just getting to the what she wants to learn with her practice is most important”.(lines 86–89)

this role is that in-between thing. I’m not an administrator. I don’t evaluate people, but also they know he talks to me. So I think that’s the biggest hindrance is what the perceived relationship with is the—with the principal.(pre-interview, 179–182)

I’m not afraid to tell him things that I think he needs to hear. He can trust me that I’m going to tell that, but then he also knows I don’t cross those boundaries with the teachers. What the teachers say to me between coaching stuff—no, you don’t need to know that.(pre-interview, lines 132–135)

3.3. RQ3: How Did the Positionings of the Coach and Teacher Manifest Within the Interactional Space, and What Characteristics Define the Nature of Their Talk During These Interactions?

3.3.1. Patterns in Conversational Topics

The work we did last year on those instructional decisions about like what to keep and what not to keep and how to focus on the main, important things about the lesson, I feel like—thank goodness. Because that almost feels like—because we did that work towards more at the beginning of the year, like I feel like that became fairly second nature to start thinking about it even through the middle of the lesson.(lines 288–294)

3.3.2. Patterns in Turn Initiation and Discourse Moves

So, to start with reviewing our norms, we had said that we’ll be honest, know that I’m here to support and to help you grow. The work is about Abby, not the kids, and the focus is on broad teaching improvement, not on the specific lessons. So is there anything you want to change or add for next year?(pre-observation cycle 1)

Yeah, I think it is more of what I would want to see from that part, because I see a lot more of the kids discussing and talking…which is, I think, a good place for me to be as the teacher, then, at least at this point, because they were coming up with good—the right way to go. So yeah, I think that that is more what I would hope versus just a guiding scaffolded questioning.(lines 72–79)

This is the first time they’ve ever reflected. Now, they want us to model drafting a reflection. I wasn’t planning on doing that. We were just going to talk about what a reflection is, and so I think that…some of the questions that I would probably be wanting is talking about like what do you already know about reflecting and giving them space.(lines 124–128)

4. Discussion

4.1. Kathy’s Bracketed Authority

4.2. Abby: Agency Within Bounds

4.3. Limitations and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, J. P., Hafen, C. A., Gregory, A. C., Mikami, A. Y., & Pianta, R. (2015). Enhancing secondary school instruction and student achievement: Replication and extension of the MyTeachingPartner-Secondary intervention. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 8(4), 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancarosa, G., Bryk, A., & Dexter, E. (2010). Assessing the value-added effects of literacy collaborative professional development on student learning. The Elementary School Journal, 111, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantrell, S. C., Perry, K. H., & Manion, B. (2024). ‘I’m pretty sure we did every idea’: Teachers’ experiences with external coaches and their relation to transformative learning. Teacher Development, 28(3), 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collet, V. S. (2012). The gradual increase of responsibility model: Coaching for teacher change. Literacy Research and Instruction, 51, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correnti, R., Matsumura, L. C., Walsh, M., Zook-Howell, D., DiPrima Bickel, D., & Yu, B. (2020). Effects of online content-focused coaching on discussion quality and reading achievement: Building theory for how coaching develops teachers’ adaptive expertise. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(3), 519–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, B., & Harré, R. (1990). Positioning: The discursive production of selves. Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior, 20(1), 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, K. E., & Powell, D. R. (2011). An iterative approach to the development of a professional development intervention for Head Start teachers. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(1), 75–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egert, F., Fukkink, R. G., & Eckhardt, A. G. (2018). Impact of in-service professional development programs for early childhood teachers on quality ratings and child outcomes: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 88(3), 401–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elish-Piper, L., & L’Allier, S. K. (2011). Examining the relationship between literacy coaching and student reading gains in grades K-3. The Elementary School Journal, 112, 83–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, C. (2019). “Doing our part”: Trust and relational dynamics in literacy coaching. Literacy Research and Instruction, 58(4), 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, N. (1990). Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. Social Text, 25/26, 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, J. P. (2014). How to do discourse analysis: A toolkit (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J. (2024). Relational literacy coaching and professional growth: An elementary writing teacher’s journey toward efficacy. Teacher Development, 3, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society (T. Burger, & F. Lawrence, Trans.). The MIT Press. (Original work published 1962). [Google Scholar]

- Haneda, M., Sherman, B., Nebus Bose, F., & Teemant, A. (2019). Ways of interacting: What underlies instructional coaches’ discursive actions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 78, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heineke, S. F. (2013). Coaching discourse: Supporting teachers’ professional learning. Elementary School Journal, 113, 409–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C. S. (2016). Getting to the heart of the matter: Discursive negotiations of emotions within literacy coaching interactions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irby, B. J., Tong, F., Lara-Alecio, R., Tang, S., Guerrero, C., Wang, Z., & Zhen, F. (2021). Investigating the impact of a literacy-infused science intervention on economically challenged students’ science achievement: A case study from a rural district in Texas. Science Insights Education Frontiers, 9(1), 1123–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J., Boardman, A., Potvin, A., & Wang, C. (2018). Understanding teacher resistance to instructional coaching. Professional Development in Education, 44, 690–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, P. (2024). Choice words: How our language affects children’s learning (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S., & Rainville, K. N. (2014). Flowing toward understanding: Suffering, humility, and compassion in literacy coaching. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 30, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., & Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88, 547–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, C. G., Luoto, J. M., & Blikstad-Balas, M. (2023). Developing teachers’ literacy scaffolding practices—Successes and challenges in a video-based longitudinal professional development intervention. Teaching and Teacher Education, 133, 104274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markussen-Brown, J., Juhl, C. B., Piasta, S. B., Bleses, D., Højen, A., & Justice, L. M. (2017). The effects of language- and literacy-focused professional development on early educators and children: A best-evidence meta-analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 38, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J. A., McCombs, J. S., & Martorell, F. (2012). Reading coach quality: Findings from Florida middle schools. Literacy Research and Instruction, 51, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, L. C., Correnti, R., Walsh, M., Bickel, D. D., & Zook-Howell, D. (2019). Online content-focused coaching to improve classroom discussion quality. Technology, Pedagogy, and Education, 28, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, L. C., Garnier, H. E., & Spybrook, J. (2013). Literacy coaching to improve student reading achievement: A multi-level mediation model. Language and Instruction, 25, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J., & Tseng, C.-M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D. A., Ford-Connors, E., Frahm, T., Bock, K., & Paratore, J. R. (2020a). Unpacking productive coaching interactions: Identifying coaching approaches that support instructional uptake. Professional Development in Education, 46, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D. A., Padesky, L. B., Ford-Connors, E., & Paratore, J. R. (2020b). What does it mean to say coaching is relational? Journal of Literacy Research, 52, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, D. A., Padesky, L. B., Thrailkill, L. D., Kelly, A., & Brock, C. H. (2023). Exploring the role of instructional leaders in promoting agency in teachers’ professional learning. International Journal of Professional Development, Learners, and Learning, 6(1), ep2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailors, M., Minton, S., & Villarreal, L. (2017). The role of literacy coaching in improving comprehension instruction. In S. E. Israel (Ed.), Handbook of research on reading comprehension (2nd ed., pp. 601–625). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sailors, M., & Price, L. (2015). Support for the Improvement of Practices through Intensive Coaching (SPIC): A model of coaching for improving reading instruction and reading achievement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 45, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailors, M., & Price, L. R. (2010). Professional development that supports the teaching of cognitive reading strategy instruction. The Elementary School Journal, 110, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, E. N., Hagood, M. C., & Provost, M. C. (2014). Creating a new literacy coaching ethos. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 30, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagorinsky, P. (2008). The methods section as conceptual epicenter in constructing social science research reports. Written Communication, 25(3), 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TeachingWorks. (2025). High-leverage practices. Available online: https://www.teachingworks.org/high-leverage-practices/ (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Troyer, M. (2017). Teacher implementation of an adolescent reading intervention. Teaching and Teacher Education, 65, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. (1986). Thought and language (A. Kozulin, Trans.). The MIT Press. (Original work published 1934). [Google Scholar]

- Walpole, S., McKenna, M., Uribe-Zarain, X., & Lamitina, D. (2010). The relationships between coaching and instruction in the primary grades. The Elementary School Journal, 111, 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M., Matsumura, L. M., Zook-Howell, D., Correnti, R., & Bickel, D. D. (2020). Video-based literacy coaching to develop teachers’ professional vision for dialogic classroom text discussions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 89, 103001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G. (1999). Dialogic inquiry: Toward a sociocultural practice and theory of education. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. J., & Zhang, D. (2019). Think-aloud protocols. In J. McKinley, & H. Rose (Eds.), The routledge handbook of research methods in applied linguistics (pp. 302–311). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Voluntary Participation (Both) | Initiation of and participation in coaching is voluntary for both coach and teacher | “So I guess I have the luxury of kind of feeling relationships out and seeing what that is so then—hey, do we want to have this conversation?” |

| Mutually Sought After Relationship (Teacher) | Coaching relationship is beneficial and important to both the coach and teacher | “it’s something that’s very mutually sought after for this coaching to happen. That she like enjoys coming in and getting to coach, and I enjoy having someone who is willing to coach” |

| Collaboration (Both) | Contributions come from both coach and teacher in discussion of outcomes and creation of materials | “…it was really positive and that it was very open—a very open collaboration, and we were able to just have some really good discussions about the learning and the teaching that the kids had” |

| Trust and Respect | Coach–teacher relationship is defined by the coach’s confidentiality and neutral assessment of teachers’ practices | “The respect and the trust between us is really important and probably the most important thing that…” |

| Flexible Coaching (Teacher) | Structure of coaching is adaptable to teachers’ needs and goals | “the way that Kay does coaching is very fluid and flexible depending on your need as a teacher. So it’s not like on this day we’re going to do a preconference, and then three days later I’m going to come watch you teach, and then three days later we’re going to do a post conference. It’s very flexible depending on what we’re doing…” |

| Long-Term Relationship (Both) | Coach–teacher relationship established over time that enables trust and respect | “the more I work with her, the closer we get and the more comfortable we are and the more we learn about how the other person works. And so we can have just better and better conversations as we go” |

| Access to Knowledge Base (Teacher) | Teachers have access to resources and rationale that guide coaching decisions. | “I think another hindrance could be just feeling like you don’t know enough about whatever initiative you’re going to try if you don’t have the knowledge base” |

| Pre-Planning | Coaching is guided by pre-determined goals established in planning meetings. | “We were able to meet and do some preplanning and have some conversations about lessons that were going to come up… And so that was really helpful and beneficial” |

| Generalizable Outcomes (Teacher) | Outcomes of coaching are not specific to one lesson, but rather are applied to teaching practices holistically. | “So when you’re coming in to watch my lesson and coming in to watch my—specifically student engagement—maybe even more specifically how the students interact with my questions and how they’re answering the questions. And then I can really, when you give me feedback on that specific thing, then I can do something with that for the next lesson” |

| Practice Approach to Coaching (Coach) | Coaching prioritizes teachers’ practices rather than student competencies and behaviors | “And it should never be about the kids… in this lesson, it shouldn’t be about, well, if the kids did this. No, it needs to be about Angela. What can Angela do to bring the kids whatever” |

| Horizontal Flow of Knowledge (Coach) | Coach–teacher relationship is defined by an equal sharing of knowledge and expertise | “I try and make the coach-ee a very equal part of it. I’m not coming in as an expert or—I’m just someone to hopefully bounce ideas off of and be able to point you in a direction to—or even just another set of eyes, because you can’t see everything” |

| Code | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Self as expert (both) | Teacher makes reference to her experience to invoke authority Coach makes reference to her knowledge to invoke authority | “Yes, as a tenured teacher, it’s me initiating—That conversation and that coaching, right” “[Abby] doesn’t have the in-depth experience that I know I’ve studied, but she at least knows the difference and knows what I’m talking about” |

| Self as learner (both) | Coach or teacher refers to self as a consumer of new information | “So taking that stance as not being an expert, and I’ll say—look, I might have to look some of this stuff up or I’m not going to know everything. That and just giving that kind of wait time, I guess, for lack of better word, seems to work” “as far as my role, I think my role a lot—is mostly keeping like an open mind and being willing to try different things and not be stuck in doing things my way” |

| Self as facilitator | Coach positions herself as responsible for guiding the conversation | “I’m supposed to help facilitate meetings. If you would like coaching, this is what I am” |

| Self as middle person | Coach refers to herself as a bridge between the teaching staff and administration team | “I think the biggest hindrances—and I don’t think a lot of people feel this, but I think is that this role is that in-between thing. I’m not an administrator. I don’t evaluate people, but also they know he talks to me. So I think that’s the biggest hindrance is what the perceived relationship with is the—with the principal” |

| Coach as mirror | Teacher positions coach as a non-evaluative presence intended to reflect back her teaching practices | “coaching is best when it can be just a very open conversation. It does not feel evaluative at all and just very—it’s very mirror oriented almost. She’s kind of like—gives me a chance to really look at my teaching more deeply” |

| Coach as resource provider | Teacher positions coach as someone who provides relevant information regarding? (best practices?) | “So being willing to share, and like I said, that—some of that is just like her being able to provide me with the resources that I need…” |

| Coach as directed observer | Teacher positions coach as someone who observes specific aspects of instruction as determined by the teacher | “That focus when they come in to coach has to be so specific. Otherwise, the feedback that I get is so broad” |

| Teacher as reflective | Coach positions teacher as independently motivated to engage in reflection on instructional practices | “[Abby] is a very thoughtful person and a reflective person. So it wasn’t as much of me… worrying where we would get to. We’re going to get to someplace good” |

| Teacher as goal-setter | Coach positions teacher as self-directed and motivated to establish goals | “…this coach-ee has very strong opinions in what she wants to work on” |

| Teacher as expert | Coach positions teacher as a knowledgeable practitioner | “I would not have brought this conversation up with anyone else, probably, in the building—because they haven’t—they don’t have the experience” |

| District as determinant of coaching agenda | Coach or teacher position the school district as having influence over coaching goals and content | “So the book I bring with me is Visual Learning Feedback, John Hattie and Shirley Clarke that we did a book study on, because feedback is our big point for the district” |

| Administration as authority | Coach or teacher position the school administration as trusting the coach and teacher | “I’m not an administrator. I don’t evaluate people, but also they know he talks to me. So I think that’s the biggest hindrance is what the perceived relationship with is the—with the principal” |

| Administration as trusting | Coach or teacher position themselves as exempt from administrative control | “I would say that at this point, administrators’ expectations are none. (laughter) There doesn’t seem to be an expectation of coaching for the tenured teachers” |

| Topic | Description | Pre-Observation Frequency | Post-Observation Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Setting meeting norms | Establishing and restating the norms the coach and teacher will use to guide their interactions | 2 | 2 |

| Recap of previous coaching | Revisiting previous coaching cycles | 1 | 0 |

| Establishing a coaching focus | Setting new goals and area of instructional focus for coaching meetings | 2 | 0 |

| Establishing a coaching plan | Determining procedural actions coach will take to observe, take notes, support the teacher | 5 | 1 |

| Setting up joint inquiry task | Establishing goals and procedures for a joint inquiry task | 0 | 7 |

| Joint inquiry task | Jointly examining and analyzing data from the coach’s observation | 0 | 7 |

| Recap of coaching plan | Restating the procedural actions coach will take | 2 | 1 |

| Reflecting on coaching plan | Sharing perceptions and impressions of how the current coaching plan is working | 1 | 0 |

| Student concerns | Discussing strengths or needs of a student or group of students | 1 | 0 |

| Unrelated | Logistics, scheduling, or other conversation unrelated to the content of literacy teaching and learning | 3 | 2 |

| Code | Definition |

|---|---|

| Suggestion for Instruction | Coach suggests an instructional action or plan for the first time during the coaching session |

| Intention | Teacher makes a new statement (not an embrace of a coach suggestion) about an instructional action or plan |

| Expansion Expansion_Declarative Expansion_Procedural Expansion_Conditional | Coach explains, expands, builds on, or makes a connection to own or teacher’s contribution, not specific to a suggestion for instruction or intention Coach provides further information specific to what the coaching or instructional suggestion/intention is Coach provides further information specific to how the teacher can implement the instructional suggestion/intention Coach provides further information about why or when an instructional suggestion/intention should be used |

| Observation | Coach/Teacher notices and names the teacher or student action (often not linked back to a previous idea) |

| Clarifying Invitation | Coach/Teacher requests more information relative to what was said in previous turn or turns. May be a restatement or rewording of the prior turn |

| Affirmation | Coach affirms an action or statement made by the teacher |

| Elicitation | Coach/Teacher invites new information about lesson content, teaching actions, or student behaviors |

| Critical Self-Reflection | Teacher reflects on teaching actions |

| Explanation | Teacher

|

| Query | -Coach/Teacher doubts, fully/partially disagrees, challenges or rejects a statement -Coach/Teacher pushes back or challenges the topic of conversation or suggestion being made by the coach

|

| Embrace | Teacher makes proactive statements related to the suggestion for instruction regarding intentions for subsequent instruction (e.g., sounds like a good idea, I’ll try it)

|

| Acknowledgment | Statement that acknowledges what was said yet that doesn’t respond positively or negatively (e.g., okay) |

| Agreement | Coach/Teacher agrees with what was previously said. (e.g., Yes, okay, that makes sense, yeah; that might be really helpful) |

| Reference Back | Coach/Teacher introduces reference to previous knowledge or contributions in the current conversation |

| Reference to Wider Context | Coach/Teacher makes links between what is being discussed and a wider context by introducing knowledge, experiences, or contributions from outside of the coaching interaction (e.g., lesson observed prior, staff or grade-level meeting) |

| Reconstructive Recap | Coach summarizes the conversation—not presenting a new suggestion for instruction—just a recap of what was previously discussed during the present or preceding meeting.

|

| Unrelated | Statements or questions unrelated to the content of teaching and learning being discussed by the coach/teacher (e.g., technology issues with recording, other duties within the school) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dunham, V.; Robertson, D.A. Discourse Within the Interactional Space of Literacy Coaching. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 694. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060694

Dunham V, Robertson DA. Discourse Within the Interactional Space of Literacy Coaching. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):694. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060694

Chicago/Turabian StyleDunham, Valerie, and Dana A. Robertson. 2025. "Discourse Within the Interactional Space of Literacy Coaching" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 694. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060694

APA StyleDunham, V., & Robertson, D. A. (2025). Discourse Within the Interactional Space of Literacy Coaching. Education Sciences, 15(6), 694. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060694