2. The Iranian Data Set

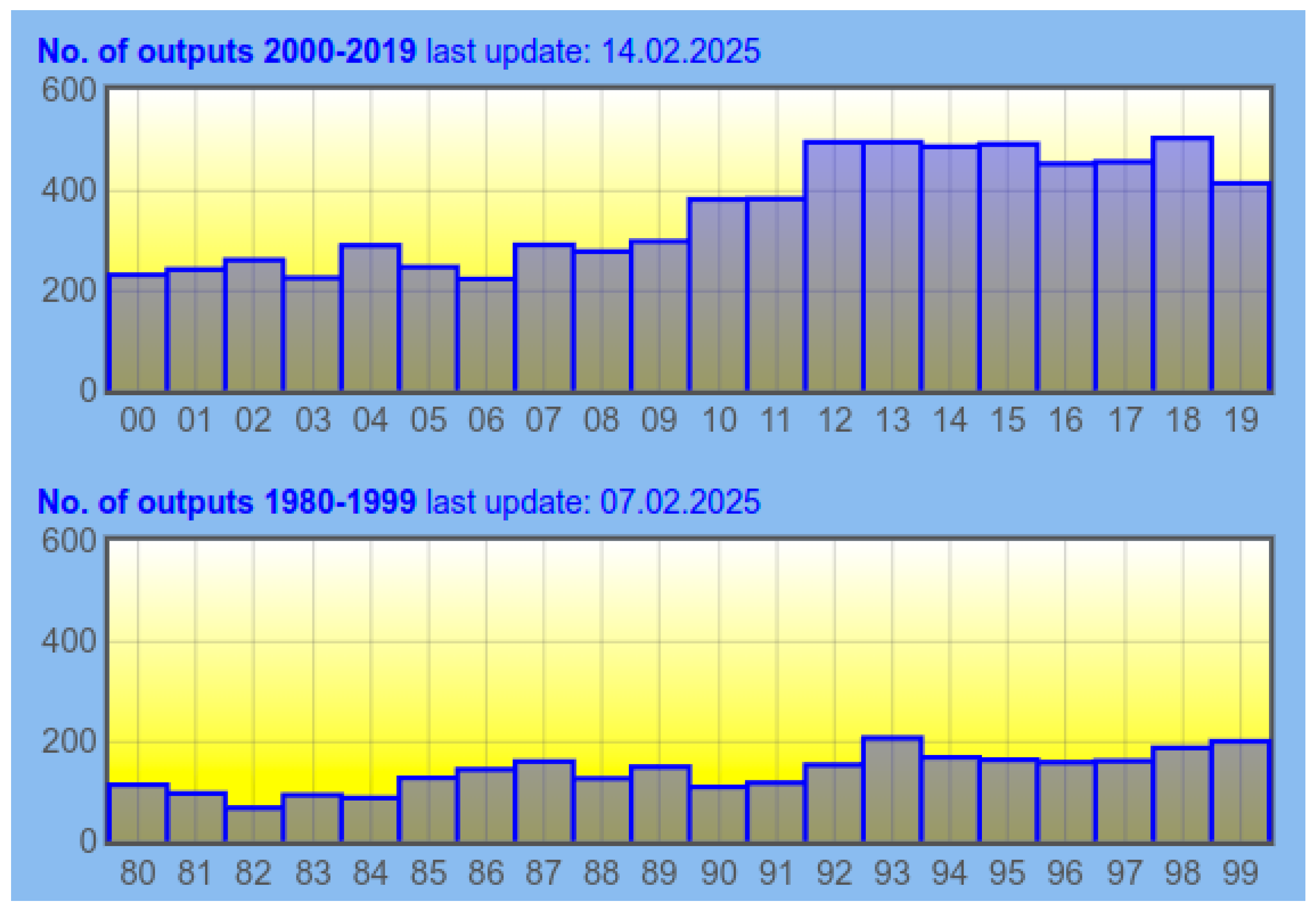

The data set to be analysed in this paper consists of a convenience sample of 153 research papers published between 2015 and 2024. These papers came to the attention of the author as a result of his regular monitoring work as editor of the VARGA database—the main bibliographical resource for vocabulary researchers (

Meara, n.d.). In effect, they were all cited in other papers that are listed in the VARGA database. In addition, each of the 153 papers contained the word

Iranian in its title. This is an arbitrary criterion, introduced as a way of limiting the sample to a manageable set of relevant papers. This point will be taken up again in the Discussion section.

The 153 papers are not listed explicitly in this report, but interested readers can identify the papers that make up the data set by referring to the VARGA database:

https://www.lognostics.co.uk/varga/ (accessed on 12 March 2025) and entering the search term

{IR} in the query box. This will generate a list of all 153 papers. Searches can be limited to a single year by adding a date to the search: e.g.,

{IR} 2015 will generate a list of the 48 papers in the database that were published in 2015.

What information can we glean from this data set? Given that the Iranian research on vocabulary is relatively unfamiliar to researchers outside Iran, our first analysis concerns who the authors of the 153 papers are.

Table 1 provides a statistical summary, which identifies the number of authors who contribute to N papers in the data set. In this analysis, each contributing author is counted, and no distinction is made between papers written by one author or several co-authors. A not insubstantial total of 279 authors are identified by this process. As usual in studies of this sort, the vast majority of these authors (83%) contribute to only a single output, but this figure is broadly in line with what we would expect for L2 vocabulary research (Meara’s analysis of the 2020 research outputs suggests, for example, that we can identify a total of 491 authors, of whom 439 (89%) contributed to only one output in that year,

Meara, 2024).

Table 1 also shows that a substantial number of authors contribute to multiple outputs, with a particularly large number of authors (34) contributing to two outputs.

Table 2 lists these prolific authors. The prolific authors are all Iranians, and there is very little evidence that they collaborate with researchers outside Iran. Most of these names will be unfamiliar to Western researchers, however, so a set of brief biographies for the most prolific authors—Nazamiandost, Gorjian, Shoari and Heidari Tabrizi—is provided in

Appendix A.

Step two of our data analysis goes beyond these superficial statistics. In this analysis, we look at who is being cited in the data set and try to identify any Significant Influences—authors whose citations are especially numerous. We do this by examining the bibliographies from each of the outputs listed in the data set and extracting from these bibliographies a list of authors who are cited therein. This analysis identifies a total of 5243 unique authors for the Iranian data set. (This figure may slightly overestimate the number of unique authors due to inconsistent practices in transliterating Iranian names and some problems identifying Chinese sources.) The vast majority of these authors—4132 of them—are cited only once in the data set, but there does appear to be a set of key authors who are cited much more frequently than this, and we can view these authors as Significant Influences in the Iranian research on L2 vocabulary acquisition.

Table 3 summarises this data, showing the number of authors who are cited N times in the data set.

Table 4 identifies the Most Significant Influences—sources who are cited more than 10 times in the data set.

The most surprising point here is that the Most Significant Influences list is completely dominated by Western researchers, rather than by home-grown Iranian researchers. Only two Iranian sources appear in this list: Gorjian (11 citations) is the only one of our prolific authors who is cited more than 10 times, though Namaziandost just misses the cut with 10 citations in the data set. Heidari Tabrizi garners only four citations, and Shoari is cited only twice. These figures are a good example of the truism that the most prolific authors are not always the most influential people in an academic field. However, Kafipour (not a prolific author in this data set) is a notable new name with 18 citations. Kafipour seems to have been very active in strategy research, but his more recent work has turned to the study of the language requirements of medical students. He holds a post at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (see

Appendix B).

The dominance of Western researchers in the citation list suggests that the Iranian research is less isolated than we might have expected. Western sanctions on Iran make everyday contact between scholars in Iran and other countries problematical, and we might have expected this to lead to the development of a distinctive Iranian approach to vocabulary acquisition. At first glance, this does not appear to be the case. However, this interpretation of the data is not as straightforward as it seems. Although all of the authors listed in

Table 4 will be familiar to readers who know the applied linguistics research literature, readers more familiar with vocabulary research in particular will have noticed some unexpected features in the data. The Iranian Most Significant Influences list, not surprisingly, is dominated by “the usual suspects” found in recent L2 vocabulary research—Nation, Schmitt, Laufer and to a lesser extent Meara, Read and Hulstijn. However, a number of authors who would usually figure in such a list are cited much less frequently than we might expect. Coxhead, for example, is cited only eight times, Peters only seven times, while Pellicer-Sanchez gets no citations in this data set. On the other hand, the list of Significant Influences in the Iranian data set contains a number of familiar authors who would perhaps not figure in an up-to-date list of Significant Influences extracted from mainstream L2 vocabulary publications. Examples of this are Oxford (37 citations), Gu (with 33 citations), Nunan (with 25 citations), Wilkins (with 21 citations), Dornyei (with 20 citations), Thornbury (with 19 citations), Folse (with 18 citations) and Carter, Skehan and Jiménez Catalán (with 14 citations each). The prominence given to these authors in the Iranian data set is rather different from the attention they get in the mainstream L2 vocabulary research literature. The most straightforward interpretation of these differences is that the Iranian research depends heavily on monographs and books, whereas the Western research makes more use of reference points that appear in journals. Particularly important in this regard is that fact that some of the cited texts are works that are not usually cited in the context of L2 vocabulary research. (

Dornyei, 2014), for example, focussed on individual differences; (

Skehan, 2018) deals with tasked based performance; (

Nunan, 2015) is mainly concerned with classroom interaction. Particularly striking influences are Schmidt’s work on noticing (e.g.,

Bergleithner et al., 2013), and RE Mayer’s work on multimedia learning (

Mayer, 2020), two sources that appear relatively infrequently in the mainstream vocabulary research. The appearance of these people in the Iranian Significant Influences list suggests that the Iranian research may be moving in a direction that makes it look rather different from the research produced elsewhere, but the evidence for this suggestion is weaker than we might have expected.

3. The Co-Citation Analysis

We can obtain a better impression of the main trends in the Iranian research by looking in more detail at the patterns of citation within this data set. The analysis reported in this section is an author co-citation analysis. The approach is based on pioneering bibliometric work by

Small (

1973) building on earlier work by

Price (

1965). This work suggests that we can identify “research fronts” in a field by examining the way authors are sometimes cited together in a set of research papers. Basically, the approach assumes that if author A and author B tend to be co-cited in a large number of papers, then these papers can be considered to share a common focus. If several authors tend to be co-cited in this way, they can be considered to form an “invisible college”—a group of researchers whose work highlights a particular theme in the research.

It is clearly not feasible to examine ALL of the co-citations in a data set with a large number of authors. Author co-citation analysis generates huge amounts of data: a single paper that references 50 authors generates 5049/2 = 1225 co-citations, while a data set of 153 papers with 5243 authors generates a mountain of data that, for all practical purposes, is just too large to process effectively. For this reason, normal practice in author co-citation analysis is to focus on the most cited authors, and we normally do this by selecting a set of about 100 frequently cited authors to work with. The data shown in

Table 3 suggests that the closest we can get to this conventional value is by setting an inclusion threshold of eight citations in the data set: 88 authors meet this threshold.

The next step involves computing the number of times each of these 88 authors is co-cited with any of the other authors. This process gives us a large matrix that we can submit to a mapping program such as Gephi version 0.10.1 (

Bastian et al., 2009).

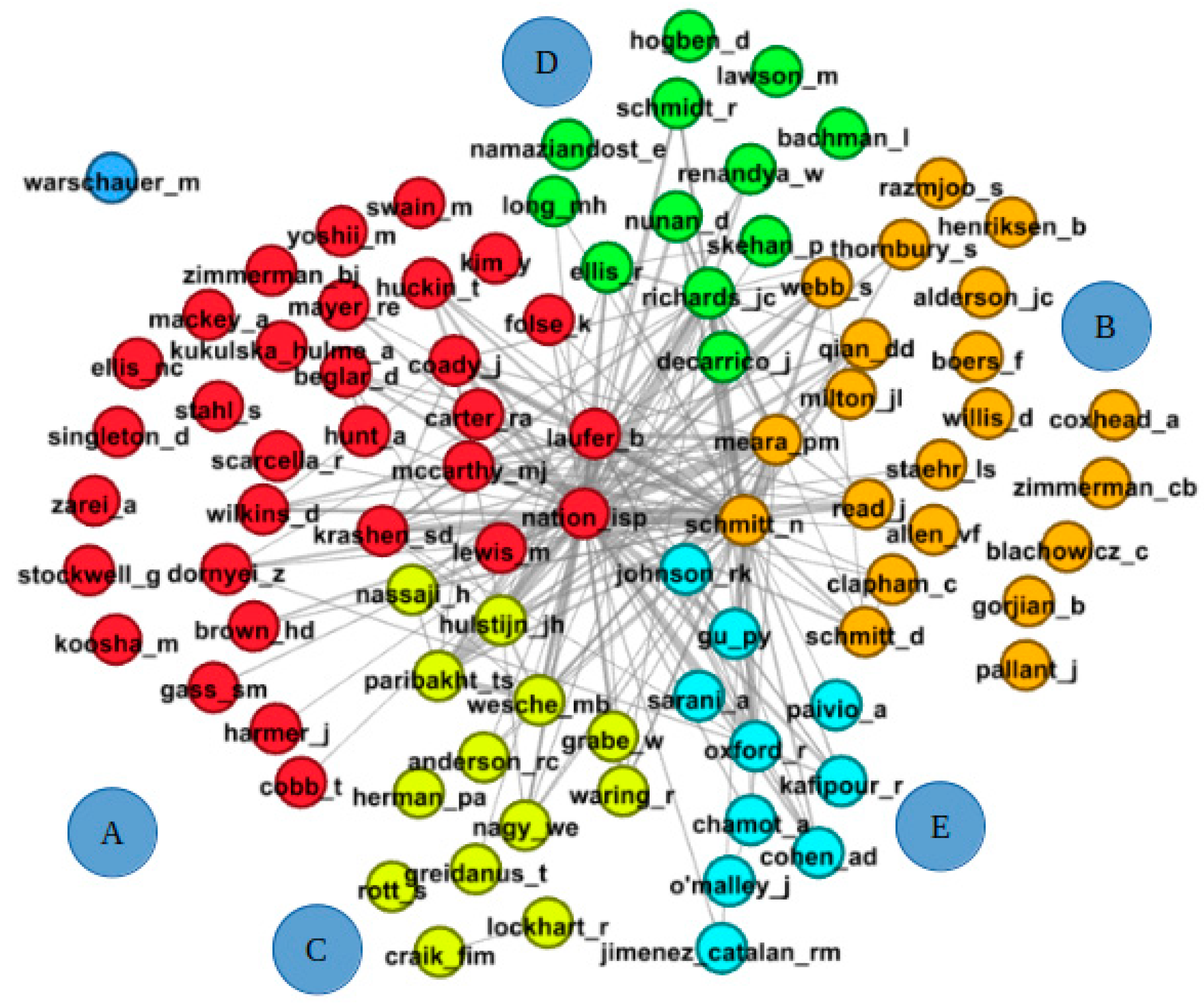

Figure 2 shows the basic co-citation map for the Iranian data set. The map shows the co-citation links between the 88 most-cited authors in the data set, but for the sake of simplicity, the map only shows links that occur at least nine times.

Gephi finds five clusters in this data (shown by the colouring of the nodes), with one disconnected node (Warschauer). However, for the moment, we will only note that the map is clearly dominated by four pre-eminent influences: Nation, Schmitt, Laufer and Meara. These four authors account for the vast majority of the co-citation links in this data set. Nation, for example is directly co-cited with 85 of the 88 other sources in this map; Schmitt has a direct co-citation link with 76 of the 88 other sources, while Laufer and Meara are directly connected with 61 and 48 other sources, respectively. The analysis in

Figure 2 is based on the 625 strongest co-citation links in the data set, and this means that these four authors account for 43% of all these strong connections. This is a problematic feature that seems to be characteristic of the recent L2 vocabulary research (cf.

Meara, 2024): the way a small number of sources dominates the network makes the network look very homogeneous, and it makes the characteristic features of small research clusters more difficult to identify. In a sense, however, the fact Nation is co-cited with almost all of the most cited authors in the data set means that he does not make a distinctive contribution to the structure of the network. This suggests that a “donut map”, which excludes sources who are very highly co-cited, might be more revealing than the all-inclusive network shown in

Figure 2.

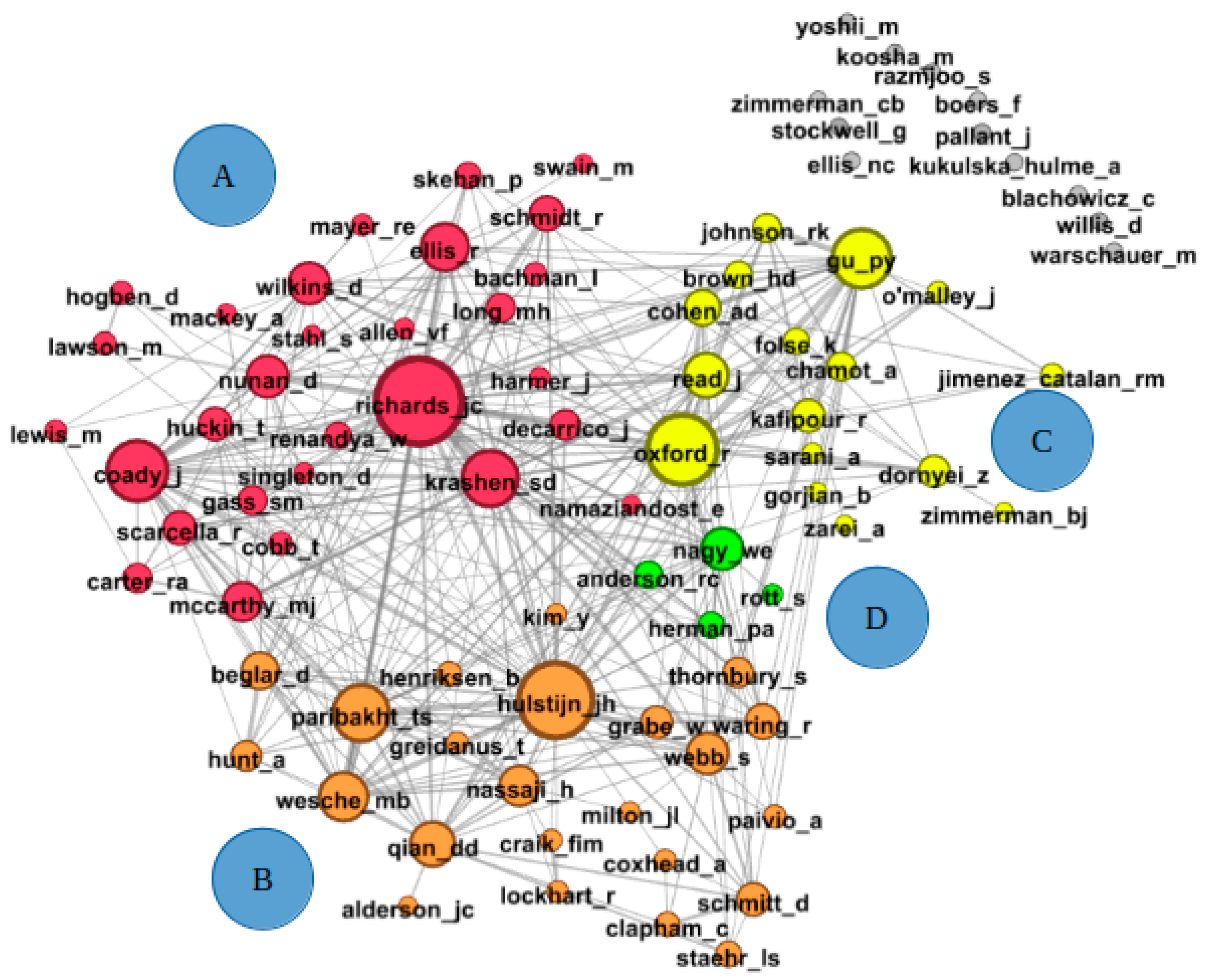

Figure 3 shows a map of this sort: Nation, Schmitt, Laufer and Meara have all been removed from this map; the resulting donut is made up of 84 sources, each cited at least eight times in the data set. The map is dominated by five sources: Richards, Hulstijn, Coady, Oxford and Gu.

Gephi identifies four clusters in this map.

Cluster A: (Richards, Coady and Krashen) This cluster seems to have a focus on L2 reading.

Cluster B: (Hulstijn, Paribakht, and Wesche). This cluster is mainly focussed on assessing “depth” of vocabulary knowledge.

Cluster C: (Oxford and Gu). This cluster is focussed on strategies and their use in vocabulary acquisition.

Cluster D: (Nagy, Herman and Anderson) This cluster is an influential L1 reading group. The map also contains a large set of twelve detached sources. These are sources who are cited at least eight times in the data set, but these eight links are individually too weak to be counted here.

Only seven Iranian sources appear in this map: Namaziandost, Gorjian, Kafipour, Sarani and Zarei, with Koosha and Razmjoo appearing in the list of detached sources. Namaziandost and Gorjian are the only prolific sources that appear in this map. Namaziandost is assigned to Cluster A, but at this level of delicacy he is co-cited only with Richards. Gorjian appears in cluster C alongside three new sources (Kafipour, Zarei and Sarani). None of these new sources appear in this data set as prolific authors, though they are responsible for significant outputs in other areas of research. (See

Appendix B).

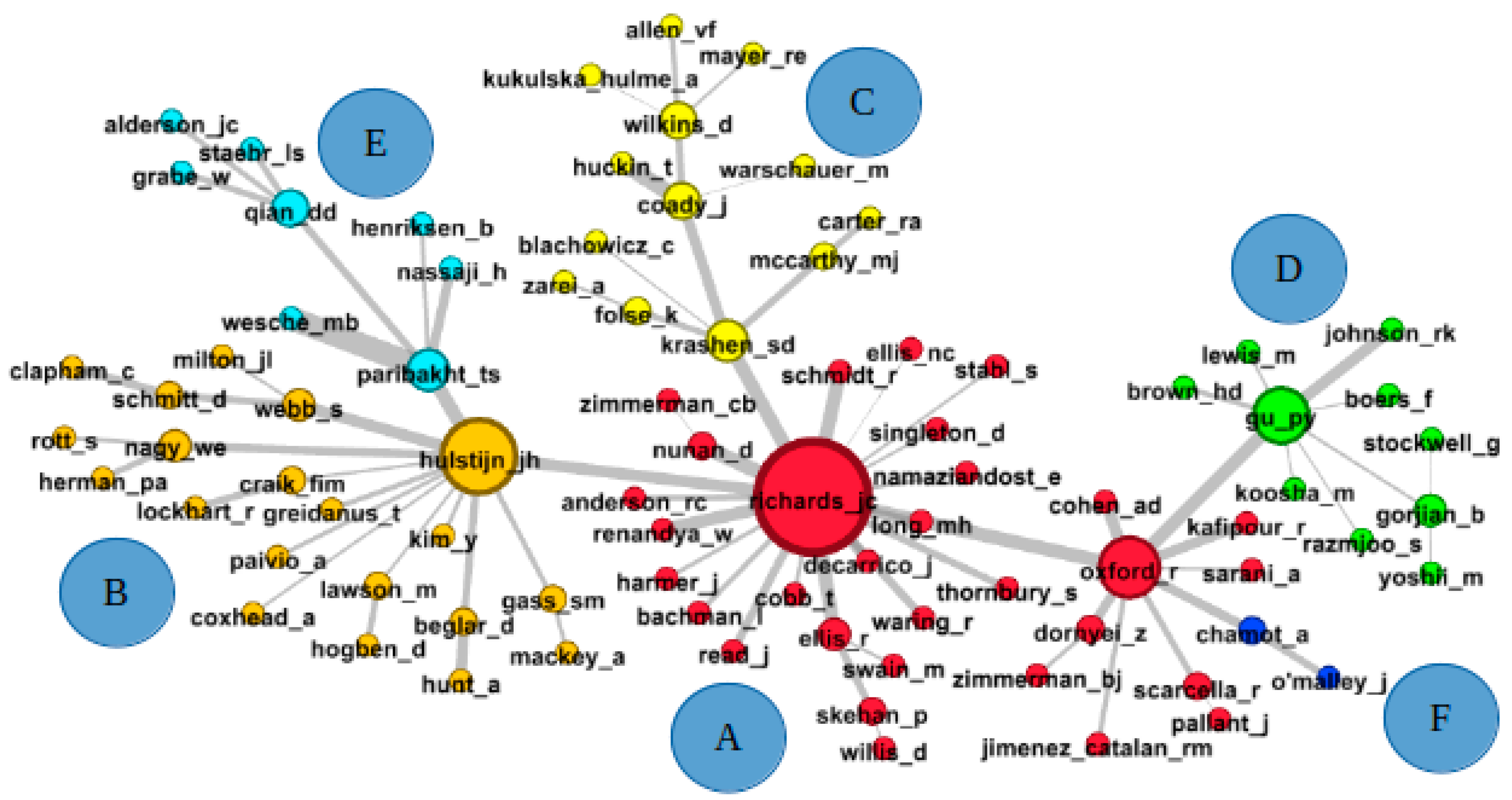

A simpler version of

Figure 3 is shown in

Figure 4. This figure is a spanning tree in which each of the 84 sources is shown connected to the node it is most frequently co-cited with.

Gephi identifies six clusters in this map.

Cluster A is the largest cluster in this network, with two hubs: Richards and Oxford. This cluster is perhaps best seen as two closely linked but separate sub-clusters. The sub-cluster focussed on Richards mostly appears to consist of major textbooks that have influenced the L2 vocabulary research but are not necessarily themselves focussed on vocabulary. So, for example, Bachman appears as a source in this cluster: Bachman’s work is mainly concerned with Language Testing. The smaller sub-cluster, focussed on Oxford, seems to be mainly specifically concerned with strategy use in general. Three Iranian influences appear in this cluster: Namaziandost clusters with the main theorists, while Kafipour and Sarani are aligned with Oxford and the strategies sub-group.

Cluster B, focussed on Hulstijn, again seems to consist of a number of distinct threads: testing vocabulary size (D Schmitt, Clapham, MiIlton, Beglar, Hunt), imagery (Lawson, Hogben, Paivio), L1 reading (Nagy, Herman) and L2 inferencing (Hulstijn, Greidanus).

Cluster C is focussed on Krashen. These influences seem to be mainly concerned with vocabulary teaching.

Cluster D, focussed on Gu, is another strategies group, with a sub-cluster interested in glosses. Three Iranian sources appear in this cluster: Gorjian, Razmjoo and Koosha.

Cluster E, focussed on Wesche and Paribakht, deals with depth of vocabulary knowledge.

Finally, Cluster F, the smallest cluster in this network, consists of two sources, co-authors of the standard text on L2 learning strategies.

Table 4 lists the strongest connections in this map. Noticeable here is that the most heavily weighted co-citation links are co-authors. It is also noteworthy that some of the strongest co-citation links recorded here are ones that do not appear as strong links in other non-Iranian data sets. Paribakht and Wesche, Richards, Krashen, Schmidt, Hulstijn, NC Ellis, Oxford and Webb all appear in the list of Most Significant Influences identified in

Meara (

2024), for instance, but the remaining sources in

Table 5 do not. This suggests that the Iranian research is only partially aligned with the mainstream vocabulary research effort.

4. Discussion

There are a number of points worth making here.

Firstly, despite the very large number of Iranian authors contributing to this data set, only a handful of them appear among the data set’s 88 Most Significant Influences. This seems to indicate that a lot of the research listed here is not being cited by other researchers. The Iranian authors frequently cite Western research, but this is a one-way relationship, rather than a reciprocal one. While it is perhaps unsurprising that Western researchers are not familiar enough with this research for it to be cited, more surprising is that the Iranian authors do not appear to be citing each other very much. Typically, a single paper in this data set cites 58 authors, of whom only a handful will be other Iranians. In a data set of this sort, we might have expected to find a regional cluster in the co-citation maps, but this does not appear to be the case here. None of Iranians who make the top 88 Most Significant Influences in this data set appears as a hub in the spanning tree (

Figure 4). A knock-on effect of this is that some of the recurring themes that can be identified from a manual search of the data set—self-regulation and autonomy, technology and CALL, the effect of learning styles, songs as an aid to vocabulary acquisition, spaced learning—do not appear as emergent clusters in the mappings. These important themes are simply not cited often enough or consistently enough for them to achieve a critical mass.

The second point to note is that the Iranian research that does appear in the maps seems to be mainly focussed on vocabulary learning strategies, on glossing and subtitling. However, this work feels slightly detached from similar work reported in Western research. The Iranian research on strategies, for example, tends to cite general texts that do not deal specifically with vocabulary strategies. Oxford, for instance, the main hub for this work, is mainly cited in connection with her textbook

Language Learning strategies: What every teacher should know (

Oxford, 1990). Furthermore, some important sources that we would expect to find cited in work of this sort (e.g.,

Pavičič Takač, 2008) do not find a mention in the data set.

What seems to be going on here is that the Iranian research tends to be dominated by very small groups working on ideas that are not widely studied in the mainstream research on vocabulary. A good example of this is the large number of papers that report studies dealing with the effectiveness of specific vocabulary learning apps—

WhatsApp, Telegram, Rosetta Stone,

Tiny Cards, Kahoot and so on. These papers share common methodological features, but they do not cite each other often enough for a co-ordinated, free-standing research cluster to emerge in the mapping. The same point can also be made for the Iranian research on subtitling that emerges in Cluster C, which similarly appears to be dissociated from related research in European publications (cf. for instance

Vanderplank, 2016).

Thirdly, a striking feature of the co-citation maps discussed earlier is that they identify a number of sources who would probably not appear in equivalent mappings of the mainstream vocabulary research. We have already mentioned the Iranian reliance on books to the detriment of more recent work published as papers, but it is also worth noting that the Most Significant Influences list contains a number of sources who do not normally figure in equivalent data sets for the mainstream vocabulary research. Gu, Skehan, Harmer, Willis, Folse and Wilkins are all more important here than would be expected. None of these sources appear as Significant Influences in Meara’s analysis of the 2020 vocabulary research (

Meara, 2024). Wilkins, for example, is most often cited here for his comment that “while without grammar very little can be conveyed, without vocabulary nothing can be conveyed” (

Wilkins, 1972, pp. 111–112), a sentiment that used to be voiced frequently in the mainstream vocabulary research but now appears only infrequently in Western vocabulary research.

At the same time, some important research themes are missing from the Iranian maps. Meara’s mapping of the 2020 research (

Meara, 2024), for example, identified ten thematic clusters in the L2 vocabulary research for that year. These included an eye-tracking cluster focussed on Pellicer-Sanchez, a word-list cluster focussed on Webb, an L1 reading cluster focussed on Nagy, an L2 uptake cluster focussed on Cobb, and a psycholinguistics cluster focussed on de Groot. None of these themes figures explicitly in the Iranian research.

These differences raise the question of whether the 153 sources analysed here are truly representative of the recent Iranian research on vocabulary, or whether they have been affected by unintentional bias in the sampling procedures. The introduction to this paper stressed that the data set analysed here was exploratory—a preliminary attempt to come to grips with the very substantial body of Iranian vocabulary research, not widely known in the West. This paper is

not a systematic review, however, and it is possible that the decision to limit the study to research outputs that contain the word

Iranian in their title will have introduced some unwanted bias into the data set. This idea is illustrated in

Table 6 and

Table 7.

Table 6 lists three examples of the type of output that has been included in the data set. A close examination of the texts suggests that using

Iranian as a title keyword might have biassed the data set towards classroom studies that use standard research instruments. Typically, studies in the data set are empirical studies where distinct groups of learners are exposed to specific teaching methods, and the effect of these methods is assessed by simple vocabulary knowledge measures. These studies typically replicate the results of earlier papers, and they often do not push any methodological or theoretical boundaries.

In contrast,

Table 7 shows three studies, selected at random, that DO appear in the VARGA data base but were excluded from the data set because they did NOT include the word

Iranian in their title. Two of these examples are clearly thematically linked, and if they had been included in the data set this might have been sufficient for a spacing theme to emerge as a distinct cluster in the mappings. (Spacing does not typically emerge as a distinct theme in the Western research, though there are a few recent of examples of work in this area (cf.

Rogers & Cheung, 2021;

Nakata & Elgort, 2021). The Iranian examples do not appear to be methodologically or theoretically innovative, however). More strikingly, two of the papers listed in

Table 6 are co-authored by Namaziandost, who we have already identified as a prolific author in the data set. Inclusion of these two papers in the data set would have consolidated Namaziandost’s role as the prolific author par eminence. Their inclusion might also have led to the identification of Namaziandost as a significant hub in

Figure 4.

Clearly, then, the analysis here needs to be treated with some caution. Specifically, it is possible that our selection criteria may have downplayed the importance of some of very prolific Iranian sources. There is obviously a lot more going on in Iranian vocabulary research than we originally realised, and not all of it has been captured by this exploratory sampling. Nevertheless, this approach has been partially successful in that it has singled out a number of Iranian authors who can be identified as Significant Influences in the Iranian research, even though their work is not well known in the West. The analysis also suggests that citation practices among Iranian authors—particularly the tendency to cite standard references in very large numbers—may have the unexpected effect of making the Iranian research less visible to Western readers than it perhaps ought to be.