Bridging Education and Geoeconomics: A Study of Student Mobility in Higher Education Under South Korea’s New Southern Policy

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the changes in student mobility in higher education between Korea and ASEAN countries before and after the implementation of the New Southern Policy?

- To what extent do these changes differ by higher education institution type, establishment, location, and mission?

- What effect has the New Southern Policy had on the mobility of ASEAN students studying at Korean universities?

2. Backgrounds and Literature Review

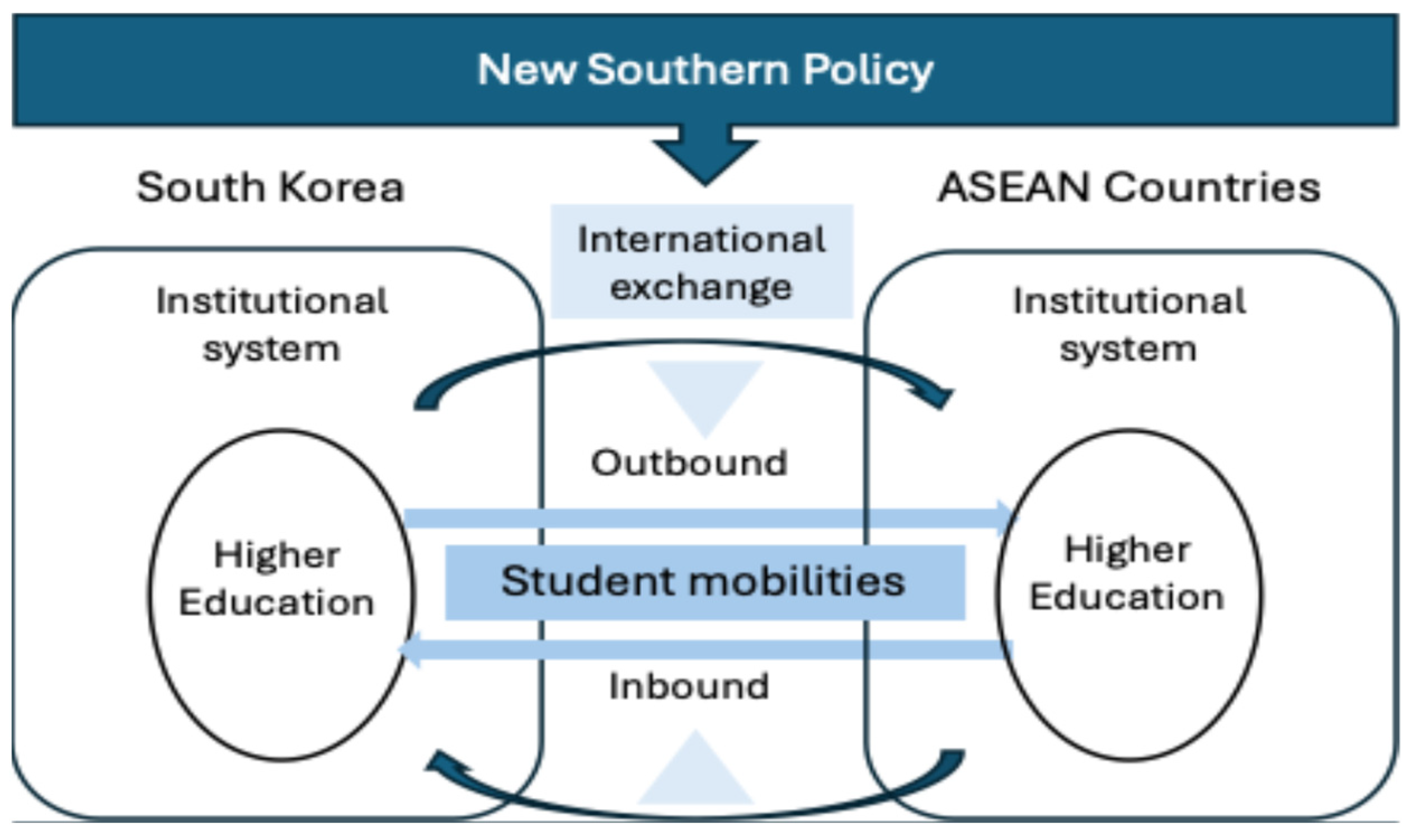

2.1. New Southern Policy1

2.2. Student Mobility in Higher Education

3. Methods

4. Findings

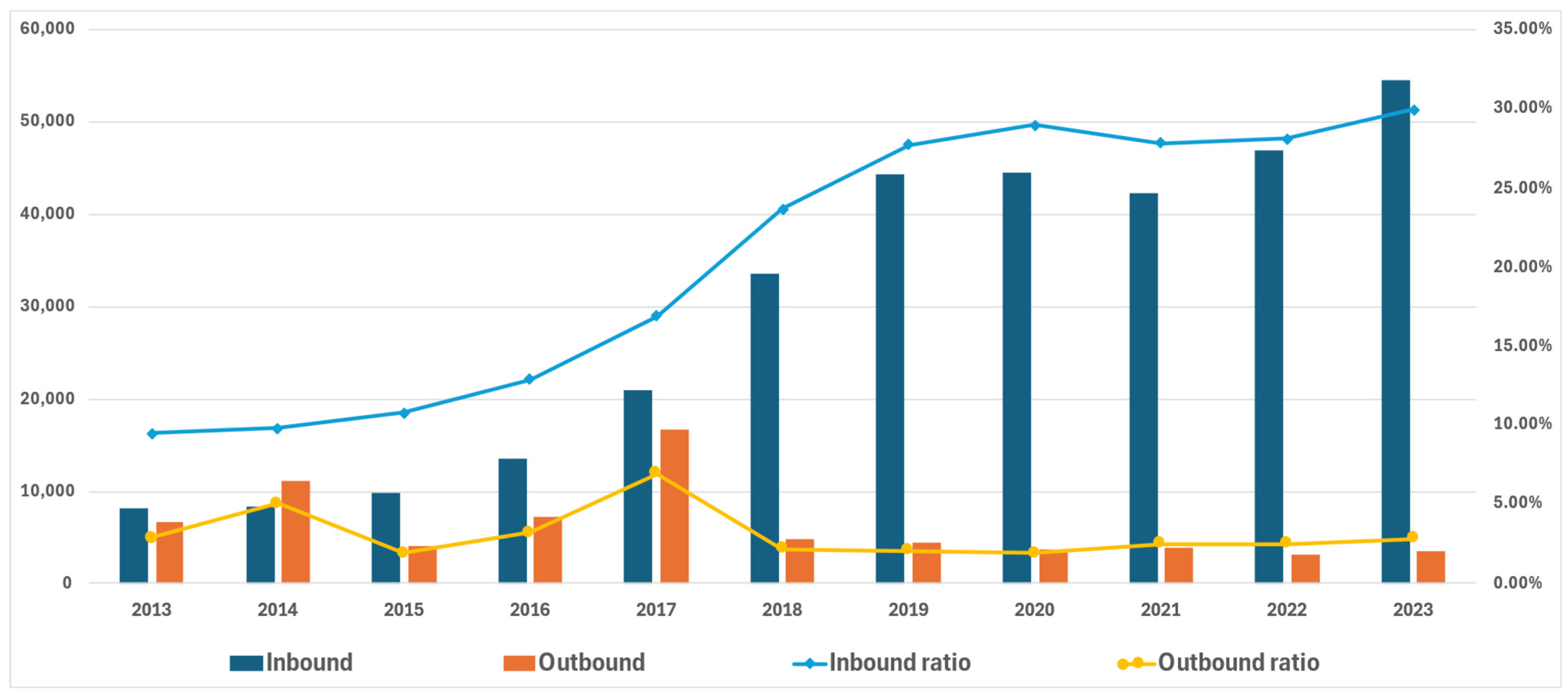

4.1. Trends in Student Mobility Between South Korea and ASEAN Countries

4.2. Patterns of ASEAN Student Mobility to Korea by University Characteristics

4.3. Effects of the New Southern Policy on the Mobility of ASEAN Students to Korean Universities

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This section of the New Southern Policy explanation is primarily derived from research reports (K. H. Lee et al., 2022; Na et al., 2020) published by the National Research Council for Economics, Humanities and Social Sciences and the Korea Institute for National Unification. The reports were written in Korean, and the main contents of this article were briefly summarized and translated from the details about the policy in the reports. |

| 2 | Data Source: https://www.moe.go.kr/boardCnts/viewRenew.do?boardID=350&boardSeq=97337&lev=0&searchType=null&statusYN=W&page=1&s=moe&m=0309&opType=N (accessed on 1 October 2024). |

References

- Alemu, A. M., & Cordier, J. (2017). Factors influencing international student satisfaction in Korean universities. International Journal of Educational Development, 57, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altbach, P. G., & Knight, J. (2007). The internationalization of higher education: Motivations and realities. Journal of Studies in International Education, 11(3–4), 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, K., & Kim, M. (2011). Shifting patterns of the government’s policies for the internationalization of Korean Higher Education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 15(5), 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S. J. (2012). Shifting patterns of student mobility in Asia. Higher Education Policy, 25(2), 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K. S., & Smith, D. (2015). A reconceptualization of state transnationalism: South Korea as an illustrative case. Global Networks, 15(1), 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W. K. (2020). New southern policy plus: Key areas and strategic direction [신남방정책플러스: 중점분야와 추진방향]. Institute of Foreign Affairs and National Security Korea National Diplomatic Academy. [Google Scholar]

- de Wit, H. (2023). Internationalization in and of higher education: Critical reflections on its conceptual evolution. In L. Engwall (Ed.), Internationalization in higher education and research. Higher education dynamics (vol. 62). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H. T., & Ong, G. (2020). Assessing the ROK’s new southern policy towards ASEAN. Perspective 7. YUSOF ISHAK Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, M. S. (2021). Education and human resource development of Korea’s New Southern Policy: Taking a step forward. In K. H. Lee, & Y. J. Ro (Eds.), The new southern policy plus: Progress and way forward (pp. 227–256). Korea Institute for International Economic Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, A. Y. C., Hill, C., Chen, K. H.-J., Tsai, S., & Chen, V. (2017). A comparative study of student mobility programs in SEAMEO-RIHED, UMAP, and Campus Asia Regulation, challenges, and impacts on higher education regionalization. Higher Education Evaluation and Development, 11(1), 12–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ifuku, R., & Takenaka, T. (2022). “Brain circulation”: The new multinational higher education partnership in East Asia—CAMPUS Asia, a Japan-China-Korea student exchange project. Bildung und Erziehung, 75(2), 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indraswari, R. (2022). South Korea’s ASEAN policy today: The New Southern Policy and its standing. Korea Europe Review, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jon, J.-E., & Jang, N. (2012). Nihao? Chinese students’ relationships with Korean students: From Chinese students’ experience and perspectives. The Korean Educational Review, 18, 303–326. [Google Scholar]

- Jon, J.-E., Lee, J. J., & Byun, K. (2014). The emergence of a regional hub: Comparing international student choices and experiences in South Korea. Higher Education, 67, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J. (2024). When massified higher education meets shrinking birth rates: The case of South Korea. Higher Educcation 88, 2357–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J., & Kim, Y. (2018). Exploring regional and institutional factors of international students’ dropout: The South Korea case. Higher Education Quarterly, 72(2), 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. J. (2017). Leveraging process evaluation for project development and sustainability: The case of the CAMPUS Asia program in Korea. Journal of Studies in International Education, 21(4), 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J. (2004). Internationalization remodeled: Definition, approaches, and rationales. Journal of Studies in International Education, 8(1), 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J. (2008). Higher education in turmoil: The changing world of internationalization. Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, L. Q., & Kim, H. K. (2011). A prediction model on adaptation to university life among Chinese international students in Korea. Higher Education, 33(1), 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. R., & Bailey, D. (2020). Examining South Korean university students’ interactions with international students. Asian Journal of University Education, 16(3), 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A. R., & Yoo, H.-S. (2022). Trends and challenges: Chinese students studying at South Korean universities. Asian Journal of University Education, 18(1), 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.-H., Cho, Y.-G., & Kim, N.-H. (2014). A study on the analysis for learning difficulties of international students in university in South Korea [한국 대학에서 유학생이 겪는 학습의 어려움 분석-중국인 유학생을 중심으로-]. Journal of Fisheries and Marine Sciences Education (수산해양교육연구), 26(6), 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Jon, J.-E., & Byun, K. (2017). Neo-racism and neo-nationalism within East Asia: The experiences of international students in South Korea. Journal of Studies in International Education, 21(2), 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. H., Park, B. S., Kim, J. G., Choi, I. A., Han, H. M., Jo, S. J., Baek, J. H., Kim, M. H., Kim, T. Y., Baek, Y. H., Lee, S. C., Lee, C. W., Yoon, J. P., Joo, D. J., Choi, K. H., & Choi, W. G. (2022). Evaluation of the New Southern Policy and directions for improvement [신남방정책 평가와 개선방향]. National Research Council for Economics, Humanities and Social Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. N. N. (2012). Regional cooperation in higher education in Asia and the Pacific. Asian Education and Development Studies, 1(1), 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Chen, L., & Liu, Y. (2025). An exploratory study of ASEAN students’ engagement dynamics with local communities in China, Japan, and South Korea. Higher Education. online publish first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCleary, R., Hay, R. A., Meidinger, E. E., & McDowall, D. (1980). Applied time series analysis for the social sciences. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Na, Y. Y., Lee, W. T., Kim, J. R., Kim, Y. C., Lee, J. Y., & Kwon, J. B. (2020). New southern policy new northern policy promotion strategy and policy tasks [신남방정책 신북방정책 추진전략과 정책과제]. Korea Institute for National Unification. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, L. (2024, October 2). South Korea, Japan lead top 7 study abroad destinations for Vietnamese students. VnExpress. Available online: https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/education/south-korea-japan-lead-top-7-study-abroad-destinations-for-vietnamese-students-4799027.html (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Ota, H. (2018). Internationalization of higher education: Global trends and Japan’s challenges. Educational Studies in Japan: International Yearbook, 12, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J. C. (2009). Classifying higher education institutions in Korea: A performance-based approach. Higher Education, 57, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I., & Kim, Y. (2022). Short-term exchange programs in Korean Universities: International student mobility stratified by university mission. International Journal of Chinese Education, 11(3), 20221006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichler, U. (2017). Internationalisation trends in higher education and the changing role of international student mobility. Journal of International Mobility, 5, 177–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. H., Brehm, W., & Kitamura, Y. (2021). Measuring what matters? mapping higher education internationalization in the Asia–Pacific. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development, 23(2), 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. (2002). University internationalisation: Its meanings, rationales and implications. Intercultural Education, 13(1), 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laos | Inbound | 96 | 96 | 97 | 108 | 116 | 109 | 102 | 104 | 117 | 133 | 144 |

| Outbound | 50 | 25 | 57 | 52 | 37 | 20 | 17 | 34 | 24 | 22 | ||

| Malaysia | Inbound | 874 | 890 | 991 | 1088 | 1177 | 1169 | 1116 | 878 | 847 | 1185 | 1226 |

| Outbound | 1182 | 803 | 1272 | 1231 | 1536 | 1712 | 1088 | 1013 | 841 | 717 | ||

| Myanmar | Inbound | 285 | 290 | 324 | 418 | 495 | 675 | 830 | 949 | 994 | 1769 | 3325 |

| Outbound | 48 | 48 | - | 88 | 97 | 87 | 100 | 84 | - | 2 | 18 | |

| Vietnam | Inbound | 3166 | 3181 | 4451 | 7459 | 14,614 | 27,061 | 37,426 | 38,337 | 35,843 | 37,940 | 43,361 |

| Outbound | 319 | 992 | 992 | 502 | 695 | 383 | 390 | 1040 | 625 | 601 | 969 | |

| Brunei | Inbound | 86 | 86 | 83 | 85 | 63 | 47 | 68 | 15 | 15 | 75 | 91 |

| Outbound | 6 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 22 | 32 | 26 | |

| Singapore | Inbound | 298 | 310 | 340 | 417 | 493 | 413 | 437 | 183 | 135 | 361 | 323 |

| Outbound | 281 | 281 | 600 | 410 | 1068 | 884 | 587 | 1128 | 1028 | 875 | ||

| India | Inbound | 753 | 776 | 899 | 888 | 963 | 1107 | 1131 | 1080 | 1116 | 1328 | 1479 |

| Outbound | 559 | 656 | 443 | 291 | 262 | 267 | 296 | 158 | 61 | 29 | 123 | |

| Indonesia | Inbound | 1025 | 1101 | 1175 | 1353 | 1334 | 1438 | 1615 | 1476 | 1779 | 2278 | 2420 |

| Outbound | 267 | 111 | 345 | 90 | 61 | 38 | 110 | 70 | 107 | 107 | 289 | |

| Cambodia | Inbound | 337 | 338 | 368 | 392 | 384 | 357 | 351 | 373 | 380 | 414 | 446 |

| Outbound | 57 | 55 | 59 | 40 | 52 | 66 | 65 | 69 | 40 | 15 | 5 | |

| Thailand | Inbound | 632 | 647 | 464 | 577 | 635 | 648 | 716 | 562 | 629 | 961 | 1009 |

| Outbound | 423 | 601 | 493 | 445 | 504 | 492 | 377 | 372 | 390 | 311 | 279 | |

| Philippines | Inbound | 621 | 641 | 653 | 682 | 657 | 657 | 622 | 560 | 519 | 531 | 685 |

| Outbound | 4668 | 7073 | 1004 | 3772 | 13,257 | 900 | 476 | 272 | 498 | 129 | 204 | |

| ASEAN | Inbound | 8173 | 8356 | 9845 | 13,467 | 20,931 | 33,681 | 44,414 | 44,517 | 42,374 | 46,975 | 54,509 |

| Outbound | 6628 | 11,054 | 4166 | 7166 | 16,629 | 4877 | 4439 | 3766 | 3918 | 3119 | 3527 | |

| 2013 | 2018 | 2023 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Establishment | Public | 37 | 19.5 | 40 | 19.5 | 38 | 17.6 |

| Private | 153 | 80.5 | 165 | 80.5 | 178 | 82.4 | |

| Location | Capital Region | 82 | 43.2 | 90 | 43.9 | 99 | 45.8 |

| Non-Capital Region | 108 | 56.8 | 115 | 56.1 | 117 | 54.2 | |

| Mission | Research | 7 | 3.7 | 7 | 3.4 | 7 | 3.2 |

| Research Active | 17 | 8.9 | 17 | 8.3 | 18 | 8.3 | |

| Doctoral | 26 | 13.7 | 26 | 12.7 | 26 | 12.0 | |

| Comprehensive | 140 | 73.7 | 155 | 75.6 | 165 | 76.4 | |

| Total | 190 | 205 | 216 | ||||

| 2013 | 2018 | 2023 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Number of International Students | Average Number of ASEAN Students | Share of ASEAN International Students | Average Number of International Students | Average Number of ASEAN Students | Share of ASEAN International Students | Average Number of International Students | Average Number of ASEAN Students | Share of ASEAN International Students | |

| Public | 485.22 | 49.97 | 14.99 | 652.30 | 140.51 | 27.99 | 625.11 | 158.08 | 33.67 |

| Private | 411.89 | 38.08 | 15.46 | 600.50 | 114.13 | 28.70 | 785.63 | 208.21 | 38.41 |

| Capital | 576.94 | 54.06 | 14.58 | 857.66 | 147.71 | 25.68 | 999.49 | 195.64 | 33.34 |

| Non-capital | 311.69 | 30.02 | 15.98 | 473.57 | 125.70 | 30.04 | 552.54 | 202.57 | 41.16 |

| Research | 2405.14 | 283.57 | 16.87 | 3242.57 | 404.86 | 18.33 | 4079.71 | 392.57 | 17.16 |

| Research Active | 1092.94 | 98.53 | 14.54 | 1708.88 | 272.65 | 20.44 | 1797.11 | 293.89 | 25.02 |

| Doctoral | 672.00 | 56.50 | 8.40 | 1182.38 | 241.92 | 22.54 | 1361.92 | 380.12 | 31.55 |

| Comprehensive | 200.60 | 18.19 | 16.70 | 317.15 | 90.26 | 30.35 | 407.76 | 152.41 | 40.76 |

| Number of ASEAN Students | Percentage of ASEAN Students | Number of Vietnamese Students | Percentage of Vietnamese Students | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trend (Year since policy) | 15.318 *** (3.053) | 1.838 *** (0.351) | 13.398 *** (3.210) | 1.961 *** (0.364) |

| Policy (Policy intervention) | 71.916 *** (11.339) | 6.095 *** (1.300) | 84.148 *** (12.090) | 7.775 *** (1.358) |

| Trend · Policy (Year since policy · Policy intervention) | −6.412 † (3.866) | 0.115 (0.445) | −7.061 † (4.086) | −0.148 (0.459) |

| R2 | 0.223 | 0.169 | 0.167 | 0.223 |

| N | 1929 (236 univ.) | 1929 (236 univ.) | 1730 (225 univ.) | 1730 (225 univ.) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, Y.; Song, I. Bridging Education and Geoeconomics: A Study of Student Mobility in Higher Education Under South Korea’s New Southern Policy. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060688

Kim Y, Song I. Bridging Education and Geoeconomics: A Study of Student Mobility in Higher Education Under South Korea’s New Southern Policy. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):688. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060688

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Yangson, and Inyoung Song. 2025. "Bridging Education and Geoeconomics: A Study of Student Mobility in Higher Education Under South Korea’s New Southern Policy" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060688

APA StyleKim, Y., & Song, I. (2025). Bridging Education and Geoeconomics: A Study of Student Mobility in Higher Education Under South Korea’s New Southern Policy. Education Sciences, 15(6), 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060688