Abstract

This study examines how Chinese and Western news media covered artificial intelligence (AI) privacy issues in higher education from 2019 to 2024. News articles were retrieved from Nexis Uni. First, non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) was employed to identify core AI privacy topics in university teaching, administration, and research. Next, a time trend analysis investigated how media attention shifted in relation to key events, including the COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of generative AI. Finally, a sentiment analysis was conducted to compare the distribution of positive, negative, and neutral reporting. The findings indicate that AI-driven proctoring, student data security, and institutional governance are central concerns in both Chinese and English media. However, the focus and framing differ: some Western outlets highlight individual privacy rights and controversies in remote exam monitoring, while Chinese coverage more frequently addresses AI-driven educational innovation and policy support. The shift to remote education after 2020 and the rise of generative AI from 2023 onward have intensified discussions on AI privacy in higher education. The results offer a cross-cultural perspective for institutions seeking to reconcile the adoption of AI with robust privacy safeguards and provide a foundation for future data governance frameworks under diverse regulatory environments.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping the global economy and society at an unprecedented rate, with industries from finance and healthcare to manufacturing exploring AI-powered optimization paths (Rashid & Kausik, 2024). The field of higher education is no exception, and AI is being used in a wide range of applications such as classroom teaching, administration, research analysis, campus safety, etc. Universities are using AI technology to enhance personalized learning, optimize the allocation of educational resources, and enhance data-driven decision-making capabilities (Strielkowski et al., 2024). However, as AI is increasingly applied in higher education, issues related to student data privacy, algorithmic fairness, ethical monitoring, and technology governance have gained significant attention from academics and policymakers (Jacques et al., 2024).

The operation of AI systems in higher education relies on large-scale datasets that may contain sensitive personal information, such as student grades, behavioral patterns, mental health, and even biometric data (Silva et al., 2024). Without proper regulation and ethical constraints, AI technology may increase the risk of the misuse of data, privacy violations, and algorithmic discrimination. For example, although AI proctoring systems can improve exam integrity, their facial recognition and behavioral analysis technologies may also infringe on student privacy and trigger controversy about data storage, consent mechanisms, and algorithmic bias. Similarly, personalized learning platforms can predict student learning behaviors and adjust teaching strategies, but their collection and long-term storage of student data may bring unforeseen ethical challenges.

Despite the global prevalence of these issues, there are significant differences in the way media report on AI privacy issues in different countries. These differences not only reflect the different law and regulatory frameworks in different countries, but also shape the public’s perception of AI governance. In Western countries, media discussions tend to focus on privacy rights, algorithmic transparency, and legal compliance. Studies have shown that AI regulations, ethics, and data privacy receive significant media attention, particularly in relation to General Data Protection (GDPR) and the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) frameworks (Ittefaq et al., 2025; Ouchchy et al., 2020). In contrast, Chinese news media tend to place AI in the framework of national scientific and technological development and education reform, emphasizing the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) and how the government-driven AI strategy balances data security and technological innovation (Ittefaq et al., 2025). This difference in media discourse may further affect the way higher education institutions in different countries adopt and regulate AI technologies.

In the context of globalized higher education, it is crucial to understand this divergence in media narratives. As the trend of transnational university cooperation, online education expansion, and global AI technology standardization continues to strengthen, how different countries report and interpret AI privacy issues may affect the formulation of university policies, the trust foundation of international academic cooperation, and even shape the global framework of future AI technology governance. In addition, from a theoretical perspective, the comparison of cross-cultural media coverage can deepen our understanding of the interaction mechanism between technology, regulations, and public opinion, and reveal how AI governance is shaped by different social, political, and legal systems. A comparative approach is particularly suitable for exploring media coverage of AI privacy issues due to the global yet culturally embedded nature of AI technologies. Media discourses reflect and shape societal perceptions, policy responses, and ethical standards differently across cultural contexts. By systematically comparing coverage from Western and Chinese media, this study reveals how differing cultural, regulatory, and political environments influence public narratives on AI and privacy, thus enriching our understanding of the global debates around these critical technological issues.

To explore this question, this study conducted a comparative analysis of coverage of AI privacy in higher education in major Chinese and Western news media from 2019 to 2024, focusing on the following three core research questions:

RQ1: What are the main issues of AI privacy in higher education as can be seen in Western and Chinese news coverage?

RQ2: How has the development of AI privacy issues in higher education evolved from 2019 to 2024?

RQ3: How do Western and Chinese news outlets differ in their sentiment orientations toward AI privacy issues in higher education?

By researching these questions, this study not only contributes to the discussion on AI governance and data ethics, but also provides practical insights for university administrators, policymakers, and technology developers who seek to balance innovation with ethical considerations. To address these questions, the study employs a multi-method approach. Topic modeling with NMF is used to identify key AI privacy topics in Chinese and Western news (RQ1); temporal trend analysis captures the evolution of topic salience over time (RQ2) and sentiment analysis examines the emotional tone and evaluative stance of media narratives (RQ3).

2. Literature Review

2.1. Application of AI in Higher Education

AI technology is gradually changing the teaching, management, and scientific research methods in the field of higher education. Its application scope covers intelligent learning analysis, personalized teaching, automatic scoring, remote proctoring, education management, and scientific research assistance (Alotaibi, 2024). At the teaching level, more and more universities use AI algorithms to analyze students’ learning patterns and implement personalized interventions based on their learning trajectories to improve teaching efficiency (Zouhaier, 2023). For example, the recommendation system based on machine learning can dynamically generate targeted learning resources and tasks based on students’ past grades, online behaviors, and learning preferences, greatly improving the accuracy and differentiation of education (Silva et al., 2024).

At the same time, the application of AI in scientific research has also attracted much attention. University researchers use natural language processing (NLP), large-scale data modeling, and automated data analysis platforms to improve the efficiency and accuracy of academic research (Nikolopoulou, 2024). Intelligent literature review tools not only accelerate the process of researchers obtaining information from massive literature, but also provide technical support for the rapid iteration of academic frontiers (Buetow & Lovatt, 2024). These developments, while promising, also raise broader questions about the impact of AI on knowledge production and academic integrity (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019). With the emergence of technologies such as generative AI (e.g., ChatGPT), the academic ecology of universities faces new ethical and practical challenges, such as the authenticity of AI-generated content, copyright, and academic misconduct (Song, 2024). When promoting the application of AI, higher education needs to balance technology-driven and ethical norms to prevent potential unfairness and abuse.

2.2. Privacy and Data Protection in Educational Contexts

With the widespread deployment of artificial intelligence technology, data privacy issues in higher education have become increasingly prominent. Universities usually have a wealth of data on students and faculty, including academic information, financial records, health data, and behavioral trajectories (Silva et al., 2024). This data is used in AI systems for a variety of application scenarios such as personalized learning, grade prediction, and behavioral analysis, promoting more accurate educational services. However, such applications also pose significant risks of privacy leakage, misuse of data, and algorithmic discrimination (Song, 2024).

AI proctoring is one of the most controversial AI applications in higher education. To prevent cheating in exams, many universities have introduced remote proctoring systems that monitor students in real time through facial recognition, eye tracking, keystroke logging, and behavioral analysis (Marano et al., 2024). Although this method has played a certain role in ensuring the integrity of exams, its highly invasive technical characteristics have also triggered discussions on personal data storage, student informed consent, and algorithmic fairness (Balash et al., 2021; Isbell et al., 2023). At the same time, when universities use biometric technologies (such as fingerprint recognition, gait recognition, and voice recognition) for attendance management or campus security monitoring, there is also a potential conflict between data security and user privacy (H. Wang et al., 2022).

In addition to proctoring and biometrics, the application of learning analytics systems in higher education also poses privacy protection challenges. Such systems predict academic performance by collecting students’ learning trajectories, classroom interactions, and test scores, but students usually cannot fully control how their personal data is used. If the algorithm is biased in the modeling and prediction process, it may further amplify educational inequality (Heiser et al., 2023). Therefore, when universities use AI for teaching and management innovation, they must establish a perfect privacy protection mechanism and data ethics framework to balance the benefits of innovation and the protection of personal rights (Soffer & Cohen, 2024; Viberg et al., 2024).

2.3. Higher Education Data Governance and AI Regulatory Policies

Faced with the privacy challenges brought by AI in higher education, countries have introduced corresponding laws and regulations to strike a balance between encouraging technological innovation and protecting personal information. In the European Union, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is considered one of the most stringent laws on personal privacy protection. It imposes strict requirements on the collection and use of AI data in universities, with particular attention to the right to know and the principle of anti-discrimination of data subjects (Milossi et al., 2021). At the same time, the Artificial Intelligence Act classifies AI proctoring, facial recognition, etc. as “high-risk AI applications” and requires more stringent compliance audits (Lazcoz & De Hert, 2023).

The United States has not yet introduced a nationwide unified AI regulatory law, but the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) have imposed multi-level constraints on university data management. FERPA requires universities to protect the privacy of student academic data and not disclose it without authorization, while CCPA gives individuals broader data control rights. These systems indirectly affect the compliance of universities in student data collection and AI use (Mittal et al., 2024; Taeihagh, 2025). In contrast, China’s Personal Information Protection Law emphasizes the combination of national-level data security and personal information rights protection, requiring universities to take more stringent protection measures in cross-border data transmission, student privacy, and AI system transparency (Ye et al., 2024). In addition, the Interim Measures for the Administration of Generative Artificial Intelligence Services put forward clear requirements for the ethics of AI content generation and proposed more detailed regulatory norms for universities to use generative AI in research and teaching activities (Migliorini, 2024). These policy differences mean that universities in different countries face different legal and cultural environments in deploying AI technology, handling data privacy, and establishing evaluation and regulatory mechanisms. This also directly affects the way universities respond to privacy challenges and the atmosphere of public opinion.

2.4. Cross-Cultural Comparison of Media Discourse and AI Privacy Issues

The media is an important force in shaping the public’s understanding of AI privacy issues, and also influences policy making and social discussions in the field of higher education to a certain extent. In the Western context, media reports often focus on individual rights and data ethics, emphasize that technology companies should assume greater responsibility, and question the impact of facial recognition, surveillance algorithms, etc., on public freedom (Marano et al., 2024). Especially in the field of universities, the media often focuses on students’ or teachers’ resistance to measures such as AI proctoring and data tracking, and questions the rationality of technology from the perspectives of academic integrity and personal rights (Balash et al., 2021; McDonald & Forte, 2021).

In contrast, Chinese media tend to place AI in the context of national science and technology development and education reform, highlighting the contribution of technology to social efficiency and innovation (Zeng et al., 2022). When it comes to higher education, reports often emphasize the government’s leading role in AI governance, highlighting the deep cooperation between universities and industry, and the teaching reform and scientific research innovation brought about by the application of technology (Knox, 2020). Although discussions on privacy issues also involve biometric technology or campus surveillance, they are usually intertwined with narratives of policy compliance and social progress, and critical voices are relatively fewer or more euphemistic (R. Wang et al., 2024).

To enhance the theoretical depth of this comparative analysis, this study incorporates several relevant frameworks from existing research. First, surveillance capitalism (Zuboff, 2019) provides context for understanding Western media’s concerns about the commercialization and ethical implications of data privacy, especially involving AI applications in education. Meanwhile, insights from critical data studies (Couldry & Mejias, 2019) explain public sensitivities about data practices, highlighting why educational technologies such as AI-driven monitoring tools attract significant ethical scrutiny. On the other hand, the analysis of Chinese media coverage benefits from insights into media systems characterized by state influence and centralized editorial practices (Stockmann, 2013). This literature underscores how media narratives, particularly around emerging technologies like AI, may reflect broader institutional and regulatory contexts rather than purely technological evaluations. Incorporating these theoretical insights helps contextualize the observed differences in media reporting on AI privacy issues across different cultural and regulatory environments.

This cross-cultural difference in media discourse not only reflects the policy positions held by different countries on AI regulation and privacy protection, but also affects the practical response paths of universities. The extent to which public opinion accepts or questions the application of AI in exam proctoring, data analysis, etc., is closely related to the way the media presents these issues. This study will further compare the relevant reports on AI privacy in higher education between Western and Chinese media from 2019 to 2024, explore the differences in topic focus, temporal evolution and emotional tendencies, and analyze the possible impact of these differences on AI policies and data governance practices in universities. By analyzing more than 600 news reports, we try to identify key themes, track changes in privacy-related discussions over time, and assess the differences in emotions and frames in the two cultural contexts. The results can provide guidance for policymakers, university administrators, and technology developers to help them develop balanced strategies to promote AI innovation without compromising the fundamental values of privacy and trust.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Sources and Collection

To explore how Western and Chinese news media reports on AI privacy issues in higher education, this study collected two datasets from Nexis Uni—a widely used academic database recognized for its comprehensive coverage of global news sources. The timeframe was set from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2024, covering key developments such as the rise of AI proctoring tools, the emergence of generative AI, and regulatory discussions around data privacy. As the research relied on publicly available news articles, no direct interaction with human subjects was involved. However, we took care to respect intellectual property rights and only archived metadata or text snippets required for analysis. All data processing followed institutional guidelines required for responsible research and was in accordance with Nexis Uni’s Terms of Service.

3.1.1. English News Data

For English articles, we used the following search query in the Nexis Uni database: (“artificial intelligence” or AI) and (privacy or security) and (“higher education” or university or college) The initial search yielded 1574 results from four major news sources: The New York Times, The Guardian, Times Higher Education, and The Chronicle of Higher Education. We selected these media outlets because of their influence and credibility in reporting on topics related to technology and education. Subsequently, through manual screening, we removed duplicates, advertisements, irrelevant articles (e.g., focusing on AI in healthcare or finance), and articles that were purely opinion-based and did not directly mention privacy in higher education. After selecting, we retained 315 articles that explicitly addressed AI-related privacy issues in higher education institutions.

3.1.2. Chinese News Data

For Chinese articles, due to the limitations of Nexis Uni’s Chinese query syntax, the initial search strategy included a combination of the two keywords AI and 人工智能 (AI). After retrieving the initial results, further filtering was performed to isolate content related to privacy in higher education. The final data came from four relatively authoritative data sources in China: China Industry Information Database (Simplified Chinese); Xinhua News Agency: Overseas Service Chinese News (Simplified Chinese); Beijing Review (Simplified Chinese); Xinhua Finance and Economics Chinese (Simplified Chinese). These sources are primarily state-affiliated, which may influence the framing of content; however, it is representative of media coverage for this study.

The original search returned 839 entries, but manual review identified and excluded articles not related to higher education or privacy issues, resulting in 347 valid entries. This multi-step approach ensured that the dataset was targeted and able to capture how Chinese media discussed the privacy challenges of AI in university settings.

3.2. Data Retrieval and Rationale

Both the English and Chinese datasets were manually selected to remove noise and ensure data quality. Given the breadth of AI topics, covering multiple fields such as healthcare, finance, and technology, it is critical to identify articles that truly address AI privacy in higher education. Inconsistent, duplicated, or purely propaganda content was removed. This meticulous process improved the comparability of the final dataset (315 English articles and 347 Chinese articles) and laid a solid foundation for subsequent analysis.

3.3. Analytical Framework

To answer three research questions—(1) key topics in AI privacy, (2) time trends, and (3) sentiment differences—this study adopted a three-pronged approach: NMF topic modeling, time trend analysis, and sentiment analysis. Topic modeling reveals key areas of discussion, trend analysis captures the evolution over time, and sentiment analysis offers insights into the media’s underlying attitudes and emotional framing, providing a holistic understanding of media coverage differences across cultures.

3.3.1. Topic Modeling with NMF

Non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) is a machine learning algorithm used for topic modeling. It decomposes high-dimensional data such as text into lower-dimensional representations called “topics”. Each topic consists of keywords with different weights, reflecting their importance within that topic. NMF is advantageous for text analysis because it generates easily interpretable topics without requiring pre-defined categories, and it ensures non-negativity, making the topics more meaningful. Compared to Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA), which assumes a probabilistic distribution of words over topics, NMF is a matrix factorization method that produces more coherent and interpretable results in short and medium-length texts (O’Callaghan et al., 2015). While neural topic models such as BERTopic and Top2Vec incorporate word embeddings and clustering, they require high computational resources and often lack transparency in how topics are constructed (Grootendorst, 2022). As our goal is to provide interpretable results in a cross-disciplinary context, NMF with TF-IDF was chosen for its balance of performance and clarity. Articles are marked as tokens, deactivated words are removed and stemmed or lemmatized. The term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) matrix of each document is then factorized to generate a set of topics. Representative keywords in each topic are analyzed to label the topic, such as “AI proctoring”, “data protection regulations”, or “generative AI”.

3.3.2. Time Trend Analysis

We use publication dates to study changes in the popularity of identified topics between 2019 and 2024, allowing for insights into how specific events (e.g., the introduction of online proctoring related to COVID-19, the release of ChatGPT) correlate with surges or changes in coverage. This temporal perspective reveals the dynamic nature of the AI privacy debate, revealing periods of heightened media attention and potential drivers behind these changes.

3.3.3. Sentiment Analysis

To examine differences in sentiment between Western and Chinese media, this study employs a lexicon-based sentiment analysis approach specifically for AI privacy discussions. While machine learning-based sentiment classifiers (e.g., BERT variants) have shown strong performance in general NLP tasks, they often require large annotated corpora and may not transfer well across culturally divergent datasets. In contrast, lexicon-based sentiment analysis offers transparency and domain flexibility, allowing us to customize sentiment categories relevant to AI ethics and privacy in higher education (Taboada et al., 2011). This approach ensures interpretability and cross-linguistic consistency, which are critical for comparative media analysis.

To ensure contextual relevance and accuracy, we develop a custom sentiment lexicon for Chinese and English texts, respectively, rather than using a pre-trained sentiment analysis model. It is important to clarify that our decision to use a lexicon-based approach does not rest on the assumption that it outperforms pre-trained models in terms of classification accuracy. Rather, the choice aligns with the goals of cross-cultural comparison, interpretability, and domain relevance. Given the lack of labeled data and the linguistic differences across the English and Chinese corpora, we did not apply pre-trained models such as BERT in this study. It is important to acknowledge that significant structural asymmetries exist between Chinese and Western media systems. Western media operate within environments generally characterized by higher levels of press freedom, diverse ownership, and editorial independence, which facilitate critical discourses and varied perspectives on sensitive issues such as privacy and surveillance. Conversely, the Chinese media environment is characterized by strong state influence, centralized editorial control, and systematic censorship, potentially constraining critical discourse and leading to more supportive or neutral narratives around AI technology and privacy issues. Recognizing these structural differences is essential for a nuanced comparative analysis of media narratives across cultures.

Firstly, the body of each article is tokenized before sentiment evaluation. For Chinese media articles, tokenization is performed using Jieba, while English articles are tokenized based on space delimiters. Each tokenized text is then analyzed using a pre-defined sentiment lexicon containing common positive and negative keywords in AI privacy discussions. Sentiment scores are determined based on the occurrence and intensity of these words. For example, words like “breakthrough” and “success” are weighted positively, while “violation” and “risk” are weighted negatively. To enhance sentiment accuracy, negative word processing is applied. Negative words, such as “not”, “can’t”, and “never”, are identified. If a negative word precedes a sentiment-laden word, the polarity of that sentiment is reversed. To ensure contextual relevance, the sentiment lexicons were manually reviewed using a subset of the articles in each language. Words were adjusted based on their use in context, and clearly ambiguous terms were refined to reduce misclassification. Although no formal validation metrics were applied, we acknowledge this as a limitation and have noted it in the discussion. This step is critical to avoid misclassification of phrases like “not improving AI privacy measures”, which should be classified as negative rather than positive. After calculating the sentiment score, each article is classified into positive, negative, or neutral sentiment categories based on its overall sentiment balance. The analysis then extends to a comparative study of sentiment trends over a period (2019–2024).

This approach ensures representativeness and comparability of English and Chinese media coverage of AI privacy in higher education. The sample period (2019–2024) covers important developments in AI policy and technology. Rigorous selecting reduces irrelevant data, while a multi-method analysis framework (NMF topic modeling, temporal trend analysis, and sentiment analysis) provides a holistic understanding of the evolving media discourse. This comprehensive approach therefore meets the need for a more comprehensive, cross-cultural investigation of AI-related privacy debates.

4. Results

4.1. Key Topics of AI Privacy in Higher Education

To answer RQ1—what are the key topics of AI privacy in higher education reflected in Western and Chinese news?—we performed non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) topic modeling on the final dataset of 315 English and 347 Chinese news articles.

4.1.1. Overview of the NMF Topic Modeling Process

Before applying NMF, we preprocessed the English and Chinese corpora. For English texts, stopwords were removed and lemmatization was applied. For Chinese texts, we used Jieba for segmentation, removed stopwords, and merged key synonyms (e.g., “高校” and “大学”). We then constructed a TF-IDF matrix. To determine the number of topics, we tested values of k ranging from three to six and selected k = four based on semantic interpretability, minimal overlap between topic terms, and relevance to the research questions. Although we did not apply formal coherence scoring, the selected model provided thematically distinct and meaningful clusters based on manual inspection.

4.1.2. Topics in Western Media

After applying NMF to the 315 English articles, four main topics were obtained. Table 1 summarizes the model output by presenting the top keywords for each topic, providing a structured and interpretable view of the topic modeling results.

Table 1.

NMF topics identified in English-language news (Western media).

Topic 1 frequently discusses major technology companies (e.g., Facebook, Google) and ongoing debates about privacy legislation such as European regulations and data-protection laws. While higher education is not the focus of the Topic, universities sometimes feature in discussions about collaborations with big technology companies or disputes involving the sharing of student data, including with social platforms or third-party technology vendors. Legislative frameworks such as the GDPR are frequently cited, as are policy debates about data processing and student consent. Topic 2 is the most education-centric topic. This topic focuses primarily on direct applications of AI in educational settings, covering everything from automated exam proctoring, personalized learning platforms, faculty training, and institutional policies. News articles in this category often highlight the impact of AI tools on student privacy, exam integrity, and the overall learning environment. It explores the integration of AI-driven platforms in the classroom, with a particular focus on data collection, online exams, and potential violations of student privacy or academic standards. Topic 3 focuses on AI-driven surveillance technologies, particularly facial recognition. While much of the discussion involves police use and surveillance of public spaces, universities also engage in discussions when campus surveillance cameras, dormitory access systems, or event security measures are combined with facial recognition tools. Concerns about data misuse and the ethics of monitoring student populations frequently appear in these articles. Topic 4 reflects on how global geopolitical tensions are affecting AI research in universities. It often touches on issues such as national security, research funding, and the potential for cross-border technology transfer. The main theme of these articles is the China–US focal point around advanced technologies, national security, and data governance. While not all articles explicitly mention higher education, universities often appear in the context of research collaborations, intellectual property disputes, or concerns about the security risks posed by technology companies.

4.1.3. Topics in Chinese Media

Similar NMF analysis of 347 Chinese articles also revealed four main topics. Table 2 summarizes the topic modeling output by listing the most representative keywords for each topic, supporting interpretation and comparison. These topics highlight how Chinese media have linked AI privacy issues to relevant national policies, digital transformation, and global governance trends in a broad discussion.

Table 2.

NMF topics identified in Chinese-language news (Chinese media).

Topic 1 focuses on AI industrialization and data security, involving university policy orientations in AI research, computing power construction, and cybersecurity. It emphasizes the role of artificial intelligence in the broader digital economy and industrial transformation. News reports often focus on cooperation between universities and technology companies, focusing on research capabilities and cybersecurity initiatives, but also acknowledging gaps in privacy protection. Although “privacy” does not appear prominently in the keywords, university research cooperation and industry are often mentioned, especially in news reports on campus cybersecurity and the integration of industry, academia, and research. Topic 2 is most closely related to the field of higher education. It focuses on the application and privacy challenges of AI in the field of education, covering the application of AI in teaching, learning analysis, student evaluation, such as student data collection, privacy risks of intelligent learning systems, etc. At the same time, it also raises questions about student privacy protection, accompanied by concerns about the abuse of personal data and the tracking of learning behavior. Topic 3 emphasizes the institutional and value issues behind AI applications, such as laws and regulations, social ethics, human–machine relations, and new risks brought about by generative AI. It reflects the Chinese media’s attention to international AI regulatory trends and China’s interest in promoting or shaping global governance structures. Overseas cases such as the United States often appear in such reports, showing the Chinese media’s continued attention to international regulation and global governance. Topic 4 involves enterprise practices of AI models, technological development, and AI research in universities. The focus is on the application of artificial intelligence in various industries and the role of universities in large-scale model development. Although privacy is not the main concern here, it comes up when discussing whether model training and actual deployment scenarios comply with data regulations. Compared with Topic 1, this topic is more inclined to technical details and enterprise applications, rather than macro-digital development or cybersecurity.

4.1.4. Comparative Insights Across Western and Chinese Topics

Although AI-related news covers a variety of areas, from regulatory debates to industrial applications to ethical governance, it is particularly illuminating to compare Western and Chinese media coverage of these issues in the context of higher education. Topic analysis of the data shows that both sides are concerned about student privacy and the integration of AI education tools. However, in terms of specific reporting content and discussion focus, Western and Chinese media show different narrative frameworks. Categories were manually constructed by clustering semantically related NMF topics into broader comparative themes. This is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparative topic analysis of Chinese and English data.

In Western media, coverage frequently centers on AI regulation and student rights, assessing whether systems violate GDPR or infringe on privacy in contexts such as AI-powered proctoring. There is also intensified scrutiny on technology companies and an emphasis on the legal responsibilities of universities to protect data. By contrast, Chinese media places greater weight on policy regulation, AI-driven educational strategies, and government-led initiatives for integrating AI into higher education. AI development is framed as part of the country’s broader digital economy strategy, which involves both opportunities and challenges, while calling for stricter privacy protection guidelines.

Despite these distinctions, student privacy emerges as a pivotal concern across both Western and Chinese media reports. Discussions address how universities manage data via proctoring tools, personalized learning platforms, or campus surveillance, highlighting significant ethical and practical risks. However, the regulatory narrative diverges: Western outlets typically reference GDPR, FERPA, and the supervision of tech companies, whereas Chinese sources tend to situate AI privacy within the nation’s overarching policy goals, focusing on governance frameworks and long-term developmental directions. Overall, while both sides recognize the privacy risks posed by AI in higher education, Western media often stresses legal accountability and individual rights, whereas Chinese media underscores balancing privacy protection with digital innovation and government-led governance.

4.2. Time Trend Analysis of AI Privacy

4.2.1. Time Trend Analysis of AI Privacy in English Media

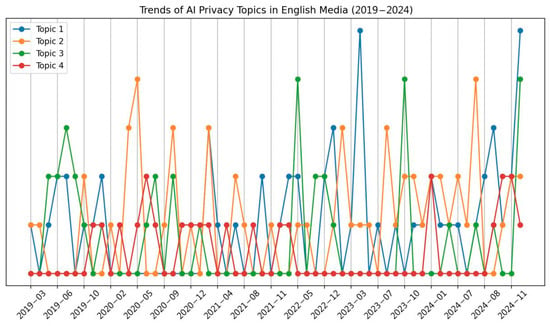

Figure 1 shows the trend of Western media coverage of AI privacy from 2019 to 2024. Overall, the attention paid to AI privacy issues has not increased linearly, but has been highly dependent on specific events, showing an intermittent fluctuation pattern. In the early phase (2019–2021), media coverage of university AI privacy remained scattered, without forming a sustained upward trajectory. Although AI proctoring (Topic 2) and facial recognition monitoring (Topic 3) experienced brief surges during 2020–2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic’s rapid shift toward remote learning, discussions were largely event-driven. Articles typically highlighted ethical concerns surrounding biometric data collection, online examination integrity, and the initial implications of GDPR. Technology company responsibilities (Topic 1) also attracted some attention amid these debates, but the focus remained on responding to specific incidents rather than establishing a comprehensive, ongoing discourse.

Figure 1.

Time trend analyses—English-language media.

Following this, reporting expanded considerably in 2022, yet continued to be driven by notable events and controversies. Topics 1 and 2 emerged as dominant themes, reflecting increasing scrutiny of university–industry data sharing practices under GDPR. During this period, high-profile student protests against AI proctoring prompted repeated spikes in coverage, centering on concerns over privacy violations and technological transparency. Simultaneously, greater emphasis was placed on how large technology firms adhered to GDPR mandates, as well as on universities’ attempts to reconcile innovation with data compliance in a rapidly changing regulatory environment.

In the peak period (2023–2024), Western media reports reached new heights, with Topics 1 and 2 commanding the greatest share of attention. Articles focused heavily on the transparency of university data governance, particularly in relation to facial recognition, personalized learning tools, and online data management under stronger GDPR enforcement. Topic 3 surged in relevance whenever legislative measures arose to restrict or ban facial recognition on campuses, prompting in-depth debates on the implications for student rights, privacy protection, and university security. Although coverage of Topic 3 was overall less frequent than Topics 1 and 2, it nonetheless drew considerable interest during periods of legislative or institutional policy change.

In contrast, Topic 4 remained comparatively peripheral in 2023–2024, with only sporadic peaks tied to restrictions on U.S.–China academic cooperation or national security legislation affecting AI research funding. While these episodes occasionally generated media attention, the broader discourse continued to focus on AI monitoring, student privacy, and technology company compliance. Overall, Figure 1 underscores that Western media reporting on AI privacy within universities has remained event-driven rather than reflecting a stable, policy-focused conversation. As GDPR enforcement intensifies, AI regulatory policies evolve, and technology companies adapt their data governance practices, it is likely that Western media coverage will continue to revolve around emergent controversies, placing legal obligations, corporate responsibilities, and the ethical challenges of AI implementation at the forefront.

4.2.2. Time Trend Analysis of AI Privacy in Chinese Media

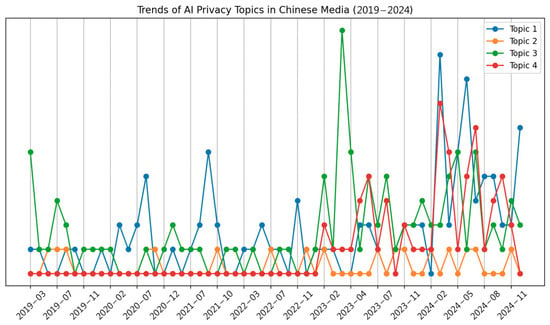

An analysis of Chinese media coverage of AI privacy from 2019 to 2024 shows that the focus of attention on this topic has undergone significant changes, reflecting broader contextual factors such as legislation, technological development, and digital reforms in higher education. As shown in Figure 2, before 2022, AI privacy was rarely mentioned in Chinese media and mostly appeared in the context of broad discussions of digital transformation or industrial policy. However, from the end of 2023 to 2024, the number of reports on AI privacy increased significantly, showing a more intensive discussion. This change was largely driven by the evolving regulatory environment, especially the policy implementation after the promulgation of the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) in 2021, and the further strengthening of generative AI governance and data security regulations in 2024. As the application of AI technology in higher education institutions continues to expand, the privacy issues of AI in education have gradually become the focus of policy and public opinion.

Figure 2.

Time trend analyses—Chinese-language media.

In this evolving media narrative, Topic 1 will see a significant increase in attention in 2024. This trend reflects the Chinese government’s efforts in recent years to strengthen cybersecurity and data governance and promote cooperation between universities and technology companies in computing infrastructure, data security, and AI industry applications. Although these initiatives have promoted technological innovation, they have also sparked discussions about the balance between university data security and national security. In particular, as universities become key hubs for the development and deployment of AI technology, how to ensure the security of sensitive data and strengthen data supervision have become important topics of media concern. In 2024, the coverage of this topic reached a peak, in line with the government’s trend of accelerating legislation and policy implementation in the fields of AI industry and digital security.

At the same time, Topic 3 began to increase significantly in early 2023, indicating that the media’s attention to AI ethical challenges and international regulatory trends has increased. Figure 2 shows that the coverage of this topic is still low in 2022, but it grows rapidly in 2023, indicating that the improvement of the AI regulatory framework is driving the media to discuss issues such as AI ethics, data governance, and international academic cooperation more frequently. In the context of AI ethics and governance issues becoming a global policy focus, Chinese media have begun to pay more attention to the role of universities in AI research and international cooperation, and how to find a balance between technological innovation, ethical responsibility, and data security. In early 2024, as discussions on AI regulation intensified worldwide, the topic’s discussion in Chinese media also increased.

Topic 4 is also one of the fastest growing topics in 2024. This topic mainly involves China’s technological innovation in generative AI, intelligent teaching systems, and adaptive learning platforms. As can be seen from Figure 2, the coverage of this topic is still relatively scattered in 2022, but it has increased since 2023. The media has widely reported on the application of AI in education and emphasized the privacy challenges it brings. For example, how to ensure the transparency and data security of AI technology in personalized learning has become a focus of media discussion. In addition, many reports pointed out the ethical and legal risks of using student and teacher data for AI training, prompting the media to call on universities to formulate clearer data protection guidelines when deploying AI applications.

In contrast, Topic 2 has maintained a low level of attention throughout the time frame and has not experienced significant growth like other topics. As can be seen from Figure 2, the amount of coverage of this topic has always been secondary between 2019 and 2024. Even if the media’s overall attention to AI privacy increases in 2024, the increase in this topic is still limited.

4.2.3. Comparative Perspectives: Western vs. Chinese Media

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the trends in Western and Chinese media coverage of AI privacy from 2019 to 2024. Although both media have shown an increase in their attention to AI, privacy, and higher education, there are significant differences in reporting patterns, drivers, and core concerns. These differences not only reflect the differences in regulatory frameworks and social values, but also reveal differences in institutional priorities.

In 2019–2021, both types of media reported less on AI privacy, but after 2022, there was a clear increase. However, there are fundamental differences in the drivers and reporting patterns in this growth. Western media coverage shows intermittent fluctuations, and the increase in attention is often driven by specific controversial events or policy interventions. For example, events such as the expansion of GDPR enforcement, student protests against biometric exams, and the review of China–US academic cooperation have all triggered short-term media booms. However, these discussions usually revolve around individual lawsuits, political debates, or technical disputes, lack systematic agenda setting, and media coverage rises and falls with sudden events rather than by long-term accumulation.

In contrast, Chinese media coverage of AI privacy has shown a policy-driven systematic growth since the end of 2022, especially after the implementation of the PIPL and the improvement of generative AI regulatory policies in 2024, and the intensity of discussion has increased significantly. Chinese media pay more attention to the role of AI in the country’s digital transformation and regard universities as key hubs for data governance and AI technology applications. Topic 1 dominates Chinese media coverage, focusing on cooperation between universities and technology companies, data security supervision, and AI industry development, while paying less attention to student privacy and AI proctoring. This trend shows that China’s AI privacy discussion is highly consistent with national strategy and revolves around the government policy framework.

The reporting pattern of Western media is mainly driven by emergencies and public opinion. Western media pay more attention to individual rights, institutional responsibilities and legal accountability, and policy changes are usually a response to public opinion rather than a dominant force in agenda setting. In addition, geopolitics is also a key driver, especially on issues such as China–US academic cooperation, data security, and technology company governance, where media attention often involves the game between national security and academic freedom. In contrast, the reporting pattern of Chinese media is dominated by national policies and regulatory frameworks, and its attention has increased significantly in 2024. However, this growth is not driven by individual events, but revolves around long-term development issues such as national policies, industrial layout, and digital reform of universities. For example, after the implementation of PIPL, reports on data governance and privacy protection have increased significantly, while the improvement of AI regulatory policies in 2024 has further promoted discussions on AI ethics, cybersecurity, and industry implementation. Compared with Western media, Chinese media tend to regard AI privacy as part of national technological development, economic growth, and global competitiveness, rather than simply focusing on individual rights or university governance.

On specific topics, Western media tend to focus on individual rights, legal responsibilities, and institutional autonomy. Topic 2 and Topic 3 occupy an important position in Western media reports, highlighting ethical issues such as privacy issues of AI proctoring, student data protection, and algorithm transparency. For example, topics such as student protests against AI proctoring, university data compliance, and the appropriateness of government regulatory measures have been widely reported in Western media. These discussions emphasize institutional accountability, legal constraints, and focus on how AI regulation affects higher education governance. In comparison, Chinese media discussions on AI privacy are more inclined to industrial policies and technological development. Topic 1 and Topic 4 have high coverage, while Topic 2 receives a lower level of attention. This trend shows that the core issues of Chinese media focus on how universities can help the development of the AI industry and how to strengthen data security supervision, while paying less attention to micro issues such as student privacy and AI proctoring disputes. In addition, Topic 3 became a hot topic in 2024, reflecting the strengthening of global AI ethical supervision and prompting Chinese media to explore the role of universities in AI ethical governance.

Despite the different reporting patterns, both types of media recognize the core role of universities in AI ethics and privacy governance. Whether in Western media or Chinese media, universities are seen as experimental fields for artificial intelligence technology, and their AI research, educational applications, and data governance practices will have a profound impact on future policy making and social norms. In both contexts, the media focused on issues such as facial recognition, algorithmic bias, and student data protection, indicating that the risks of AI in higher education have become a common concern worldwide. In addition, geopolitical factors also affect media reporting in both countries. Western media are more concerned about academic freedom, intellectual property rights, and national security, while Chinese media are more concerned about the impact of international AI regulatory trends on domestic policies and how to maintain technological advantages in global competition.

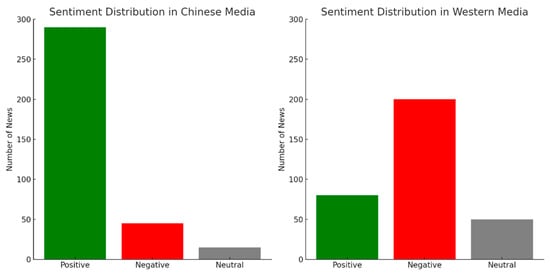

4.3. Results of the Sentiment Analysis

This section presents the results of a sentiment analysis of AI privacy discourse in Chinese and Western media from 2019 to 2024. The results show that people have very different sentiment patterns and topic concerns in different media environments, which reflects the diverse manifestations of AI privacy issues in different sociopolitical environments. Figure 3 displays the sentiment distribution of AI privacy discussions in Chinese and Western media, respectively. The results indicate that Chinese media show overwhelming positive sentiment on AI privacy-related issues, with more than 80% of news with positive sentiment. Neutral and negative sentiments are relatively rare. The sentiment distribution of Western media is more diversified, with a much larger proportion of negative and neutral articles than in Chinese media. Although positive sentiment still dominates, negative articles also occupy a considerable proportion, indicating concerns about AI surveillance, data privacy risks, and regulation issues. Chinese media cover the development of AI in a very positive and government-supportive way, emphasizing technological innovation and industry growth. Western media are more critical in their coverage, often highlighting ethical issues, data protection challenges, and governance problems.

Figure 3.

The sentiment distribution of AI privacy discussions in Chinese and Western media.

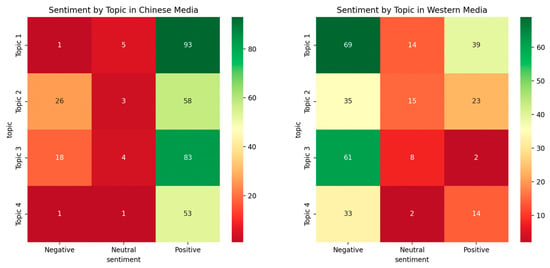

Next, we explore the sentiment distribution of AI privacy topics in Chinese and Western media from 2019 to 2024 to analyze how the media shapes the public discourse on AI privacy in different social environments. Figure 4 shows the sentiment share of the four main topics. The results show that Chinese media as a whole presents a highly positive sentiment tendency, while Western media show a more critical and diverse sentiment distribution.

Figure 4.

Sentiment analysis of four topics in Chinese and English media.

In Chinese media reports, AI privacy issues are mainly placed in the framework of technological progress and industrial development, showing an overall positive emotional pattern. In particular, the proportions of positive emotions in reports related to digital industry and cybersecurity (Topic 1) and governance and ethical supervision (Topic 3) are as high as 93% and 83%, respectively, indicating that AI is more often shaped as a core tool to promote national scientific and technological development, promote educational modernization, and enhance governance capabilities in Chinese media discourse. In the field of higher education, AI is widely used in intelligent teaching, educational governance optimization and campus safety management, while critical discussions around privacy risks are relatively rare. However, the topic of AI and student privacy in higher education (Topic 2) shows a certain degree of emotional differentiation, with negative emotions accounting for 26%, higher than other technology-related topics. This trend may reflect that AI proctoring, data governance of personalized learning platforms, and student privacy protection have begun to receive a certain degree of attention in Chinese media, but compared with the positive narrative of industrial policy and technological innovation, they have not yet become mainstream topics.

Western media reports on AI privacy issues showed a higher proportion of negative sentiment, especially when it came to technology company governance (Topic 1) and AI monitoring and facial recognition (Topic 3), with negative reports accounting for 69% and 61%, respectively. This trend reflects the Western media’s highly critical attitude towards the power of large technology companies in AI data governance, the effectiveness of government regulation, and the threat that AI technology may pose to privacy rights. In the field of higher education in particular, the use of technologies such as AI proctoring, student data tracking, and biometric recognition has become the focus of negative reports. For example, Topic 2 (AI applications in higher education) has a negative sentiment ratio of 35% in Western media, indicating that the media has shown a more critical stance on how the application of AI in education affects students’ privacy rights and data security. This reporting pattern not only highlights Western society’s concern about data rights and academic freedom, but also reflects concerns about the commercialization of educational technology, algorithmic bias, and the abuse of student data.

This difference in emotional patterns is mainly influenced by policy orientation, media agenda and higher education governance system. In China, artificial intelligence has become an important part of the national science and technology development strategy and education digital reform. The application of artificial intelligence technology in educational scenarios is more often described to improve teaching efficiency, promote educational equity and optimize school management. With the advancement of intelligent campus construction, AI proctoring, learning data analysis and intelligent decision support systems have been widely adopted, while discussions on privacy protection and ethical governance are usually incorporated into the framework of data security supervision and technology optimization in policy discourse, rather than as independent controversial issues. In addition, the management model of Chinese universities makes the application of artificial intelligence mainly led by the government, emphasizing the combination of education digital reform and national policies, which further shapes the media reporting model dominated by positive narratives.

In contrast, the higher education system in Western countries is more decentralized, and data governance relies on the autonomous decision-making of each university and is subject to multiple laws and regulations. Therefore, Western universities are more controversial on the issue of AI privacy, especially on issues such as student monitoring, biometric data storage, and the fairness of personalized learning algorithms. The public’s concerns about technology abuse and rights infringement are more prominent. In addition, due to the deep cooperation between Western universities and technology companies in AI research and data sharing, the media has raised more questions about how academic institutions can maintain data transparency and protect student privacy. This discussion mode not only leads to a high proportion of negative emotions, but also further promotes the legal and ethical game between higher education institutions, government regulators, and civil society.

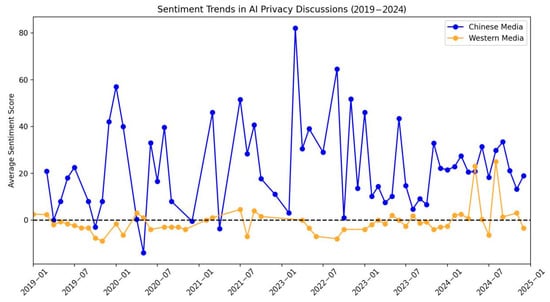

Figure 5 shows the trend of the average sentiment score, with significant differences in the sentiment expressions of Chinese media (blue line) and Western media (orange line). The results show that Chinese media as a whole show a consistently high level of positive sentiment, while Western media show a more stable and negative sentiment tone.

Figure 5.

Trend changes in sentiment analysis.

In the Chinese media, the sentiment score generally remained in a relatively high positive range, and since 2020, sentiment fluctuations have increased significantly. In particular, during 2021 and 2022, the sentiment score showed multiple significant peaks, indicating that the frequency of reporting on AI privacy issues increased during this period, and the overall reporting content tended to emphasize the positive impact of technological development. This trend is highly consistent with a series of AI and data governance-related policies issued by the Chinese government during this period. For example, the promulgation and implementation of the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) in 2021 has made the media discourse on AI privacy protection more systematic, but the focus of discussion is still on how to balance data security and industrial innovation through technological governance, rather than simply criticizing privacy risks. In addition, in 2022, the Chinese government further strengthened its support for AI infrastructure, digital economic development, and smart education applications, and the positive narratives of AI-enabled education governance, smart learning platforms, and automated management systems in media reports increased significantly, driving the rise in sentiment scores.

The sentiment trend in Western media shows a more stable but overall low sentiment score, with a much smaller sentiment fluctuation than that in Chinese media, and most of the time it remains close to zero or negative. This trend shows that Western media are more critical in discussing AI privacy issues and more cautious about the application of technology. In particular, the sentiment score of Western media has dropped significantly during the 2020–2021 period, a phenomenon that may be related to the large-scale application of AI technology in education during the COVID-19 epidemic. For example, the popularity of AI proctoring systems, the widespread use of facial recognition technology, and algorithmic decision-making in personalized learning platforms have made data privacy and surveillance controversies the focus of media attention. Due to the long-term high sensitivity of Western society to data protection, academic freedom, and technological ethics, the media has a more critical attitude towards the use of AI in higher education, emphasizing student privacy rights, algorithmic transparency, and the potential ethical risks of university cooperation with technology companies, which has led to a decline in the overall sentiment score.

Entering 2023–2024, the sentiment trends in the two types of media continued the existing pattern. Although the sentiment scores of Chinese media fluctuated during this period, they remained at a high level overall and positive reports still dominate. The sentiment trend in Western media showed a relatively stable pattern with a high proportion of negative emotions, indicating that this issue is still mainly regarded as a regulatory and ethical challenge in Western society, rather than a simple technological opportunity. In early 2024, the sentiment scores of Western media fell to the negative range at multiple time points, which may be closely related to the strengthening of AI regulatory policies in Europe and the United States, the strengthening of scrutiny of large technology companies, and the adjustment of university data governance policies. For example, Europe and the United States introduced a series of data protection bills on AI applications between 2023 and 2024, which put forward stricter regulatory requirements for data sharing, algorithm transparency and the use of monitoring technology between universities and technology companies, which further intensified the media’s critical discussion on AI privacy issues.

This trend has important implications for AI policy and data governance in higher education. Judging from discussions in the Chinese media, the application of AI in higher education is still centered on the country’s digital reform, emphasizing that technology can empower educational innovation, improve teaching quality, and optimize management efficiency. Therefore, when reporting on AI proctoring, student data analysis, and personalized learning platforms, the media usually describe them as positive manifestations of technological progress rather than potential threats or privacy risks. In contrast, Western universities face stricter data privacy laws and ethical constraints, which require the application of AI in education to be adjusted within the regulatory framework. When reporting on technologies such as AI proctoring, automatic grading systems, and student behavior data analysis, the media generally emphasizes data ethics, privacy rights, and academic autonomy and regards them as technical applications that require stricter supervision and transparency review.

5. Discussion

This study explores how Western and Chinese media report on AI privacy issues in higher education, and reveals the differences in AI privacy discourse in the two media environments through topic modeling (RQ1), time trend analysis (RQ2), and sentiment patterns (RQ3). The study found that although both types of media focus on the impact of AI on university data governance, student privacy, and academic freedom, there are significant differences in reporting frames, drivers, and sentiment patterns. This section further discusses the underlying reasons for these differences and their possible policy implications around three research questions.

5.1. Reflections on Key Topics

The topic modeling outcome shows that there are clear differences between the emphasis of Western and Chinese media reporting on AI privacy issues. In Western media, AI proctoring, facial recognition, and student data security have become core issues, and related reports mostly emphasize privacy protection, algorithm transparency, and university governance responsibilities. More specifically, the privacy risks of remote proctoring tools have become a widespread controversy faced by Western universities, and some universities have banned or restricted the use of AI proctoring technology due to student protests, legal proceedings, and public criticism. This trend is consistent with the high attention paid by Western society to individual privacy rights, data compliance, and technological ethics. In addition, Western universities’ collaboration with big tech companies has also been a subject of media controversy, especially when it entails the commercialization of student data and the trade-off between academic autonomy and government regulation, where critical reporting prevails.

Comparatively, Chinese media tend to discuss AI privacy issues from the perspective of technological development, policy guidance, and industrial upgrading. The application of AI in higher education is described to improve teaching quality, optimize education management, and enhance the country’s scientific and technological competitiveness, while privacy issues are usually included in discussions of data governance and technical specifications rather than independent ethical disputes. For example, the adoption of intelligent learning platforms, personalized teaching systems, and AI-powered education management at Chinese universities are more likely to be reported as ways to improve educational equity and efficiency rather than as potential privacy risks. Even in reporting about data security and ethical governance, Chinese media still emphasize how government regulation and technological optimization can mitigate problems rather than questioning the legitimacy or rationality of AI.

This difference shows that different legal systems, data regulatory frameworks, and education policy orientations play an important role in shaping media coverage. Western media emphasize individual rights and institutional accountability, making privacy issues a core discussion point for AI in higher education, while Chinese media tend to view AI as an important part of education digital reform, and privacy issues are embedded in the grand narrative of national governance and industrial development.

5.2. Factors Affecting Time Trend Changes

Time trend analysis shows that media attention to AI privacy issues does not grow linearly, but is driven by policies, technological breakthroughs, and social events. Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, the popularity of distance education and AI proctoring has made AI privacy a core issue in global higher education governance. Western media criticism of AI proctoring systems peaked during this period, mainly focusing on algorithmic bias, data compliance, and student autonomy. Negative sentiment in media reports reflects public concerns about student privacy protection and the legal and ethical challenges faced by universities in data governance.

Chinese media coverage during this period focused on how to use artificial intelligence technology to support remote teaching and ensure educational fairness and efficiency. AI proctoring technology is widely used in China, but negative topics such as algorithm bias and infringement of student rights are rarely seen in media reports, which rather emphasize technological progress and optimization of educational management. Although privacy issues are occasionally mentioned, they are usually placed in the framework of government supervision and technological improvement, rather than becoming part of the public confrontational topic.

Another important driving factor is the rise of generative AI in 2023, whose application in higher education has triggered extensive discussions on academic integrity, intellectual property, and data privacy. Western media generally regard generative AI as a potential disruptor of educational paradigms, emphasizing that it may pose challenges to academic evaluation, fairness, and regulatory frameworks. Discussions in Chinese media, on the other hand, focus more on how to promote the reasonable application of AI in educational innovation through technical governance and policy supervision. Regulations such as GDPR and PIPL have put forward different compliance requirements for data governance in universities. These policy changes have triggered continued attention on university data responsibility in Western media, while in Chinese media, they are more regarded as part of national governance optimization.

5.3. Different Perspectives and Policy Implications

In media sentiment, the findings show that Western media often report negative or critical sentiments on AI privacy, referring to instances where individual rights or freedoms are threatened. Reports often question whether universities and tech companies respect user consent, avoid inappropriate surveillance, and offer algorithmic transparency. Such criticisms have the potential to shape university governance and prompt public pressure for stricter compliance measures, such as banning the use of certain surveillance software or implementing strict data protection protocols. Chinese media sentiment patterns are more inclined towards neutral or positive news reporting, which can nudge policymakers towards a more balanced stance to reach an optimal trade-off between AI development promotion and data security protection. Since the application of AI in Chinese higher education is guided by national policies and regulatory frameworks, privacy issues tend to be framed as a component of technology governance rather than hot social controversy. As a result, Chinese universities prefer to address privacy issues through industry standards and policy coordination rather than public scrutiny or legal challenges.

This difference in media sentiment could have a profound impact on the future development of AI policy in higher education globally. Western countries may continue to pursue a stricter AI regulatory framework through legal constraints and public engagement, while China may adopt a government-led, technology-optimized approach to strike a balance between developing AI applications and enhancing privacy protection. In the context of globalization, such different policy paths may affect future international educational cooperation, transnational academic data governance, and compliance strategies of technology companies in global markets. These insights suggest that the AI privacy debate cannot be divorced from the social and policy context in which it unfolds. By understanding the event-driven surge in attention and cultural perceptions, universities and policymakers can more effectively anticipate challenges, align regulations with ethical requirements, and capitalize on the educational potential of AI without compromising fundamental rights.

Interpreting media sentiment on AI privacy requires careful attention to structural differences between Chinese and Western media systems. Western media narratives often reflect pluralistic debate and journalistic norms that emphasize critical inquiry and public accountability. In contrast, Chinese media operate within a more centralized environment shaped by national policy objectives and editorial guidance, where positive or neutral sentiment may reflect institutional alignment rather than outright endorsement (Stockmann, 2013). In addition to institutional factors, cultural values also play an important role in shaping media discourse on AI privacy. Western cultures tend to emphasize individual rights, transparency, and legal accountability, which may encourage more critical coverage of data collection and surveillance. In contrast, Chinese culture places stronger value on collective well-being, social harmony, and technological progress aligned with national goals (Hofstede, 2011). These cultural orientations contribute to the different ways in which AI privacy is framed in the media. Therefore, cross-cultural sentiment analysis should be interpreted in light of institutional structures and cultural communication norms, rather than as a straightforward expression of support or opposition.

Our comparative findings must be interpreted in light of structural differences between Chinese and Western media systems. The Chinese-language news corpus primarily consists of articles retrieved from four authoritative and widely circulated sources via Nexis Uni. These sources are primarily state-affiliated and generally operate within a centralized media environment characterized by editorial alignment with national policy objectives. In contrast, the Western corpus includes a wider range of commercial and independent outlets. These systemic differences in media governance and institutional autonomy likely contribute to the observed variations in sentiment and topic framing. Although this study does not perform a detailed source-level comparison, we acknowledge that further analysis of source diversity—particularly within Chinese media—would add valuable insight and remains a promising direction for future research.

6. Conclusions

This study explores how Western and Chinese news media report on AI privacy issues in higher education and focuses on three research questions: (1) What core themes emerge in media discussions on AI privacy? (2) How do these discussions evolve between 2019 and 2024? (3) What are the differences between Western and Chinese media in their views on AI privacy issues? Through methods such as NMF topic modeling, time trend analysis, and sentiment evaluation, this study reveals that higher education data governance, AI-driven proctoring, and campus surveillance are the common focuses of both types of media. However, Western media’s reporting pattern is more event-driven, often forming short-term hot spots around policy disputes or public protests, while Chinese media’s reporting maintains a more consistent growth trend with national policy adjustments and legislative advancement.

6.1. Implications for Higher Education Governance and Policy

The findings of this study have important implications for university governance, policymakers, and educational technology developers. This study points to the need for universities to set clearer standards for data governance, algorithmic transparency, and ethical responsibility. For example, Western universities face stricter regulation of student privacy under data protection laws, while Chinese universities are more concerned with balancing technological innovation and data security under government-led AI development strategies.

Secondly, the difference in sentiments between Western and Chinese media on AI privacy issues suggests that global higher education institutions must fully consider different legal systems, societal expectations, and ethical stances when collaborating across borders. For example, when it comes to international academic collaboration, data sharing agreements, and AI research compliance, Western universities tend to emphasize privacy and institutional responsibility, while Chinese universities are more concerned with technical standards, policy regulation, and industry development goals. This means that when formulating AI-related policies, higher education institutions need to adapt to the regulatory requirements of different countries and establish transparent and responsible data management mechanisms in academic collaborations.

In addition, the role of AI in higher education has gone beyond the technical tools themselves and has become a key issue at the intersection of national policies, academic governance, and social values. China’s policy orientation shows that AI is not only an educational technology innovation, but also an important part of promoting the national digital strategy. Therefore, higher education institutions need to adapt to AI-driven educational changes in the ever-changing policy environment, while ensuring the sustainability of data security and ethical principles.

Beyond these practical implications, this study also offers theoretical contributions to the fields of AI ethics, media studies, and higher education governance. It applies a mixed-methods approach combining topic modeling, temporal trend analysis, and sentiment analysis to cross-cultural media corpora. By situating media sentiment within both institutional and cultural frameworks, the study advances understanding of how AI privacy is framed differently across systems, and highlights the methodological value of integrating computational tools with comparative discourse analysis.

6.2. Research Limitations

Although this study provides in-depth insights into how the media shapes the AI privacy discourse, it still has the following limitations. Firstly, the data source is limited to news media and may not fully reflect the direct views of university administrators, students, and faculty. Future research can further verify the relationship between media coverage and actual policy decisions through interviews, questionnaires, or university policy analysis.

Secondly, this study acknowledges several methodological limitations related to topic modeling and sentiment analysis. While computational tools were used to classify sentiment in media texts, such tools may have difficulty capturing implicit emotions, sarcasm, or culturally specific affective expressions, especially in politically sensitive or editorially constrained environments. In addition, the selection of the number of topics (k) and the sentiment labeling process were based on manual evaluation rather than automated validation. Although multiple k values were tested and topic distinctiveness was assessed qualitatively, no formal scoring procedure was applied. We acknowledge this as a methodological limitation and suggest that future studies incorporate automated evaluation techniques or supervised topic alignment to enhance analytical rigor.

Further, this study mainly analyzed mainstream news media in the West (English) and China (Chinese), and did not include other information sources such as social media, industry reports, and policy documents. Social media platforms (such as Twitter and Weibo) may contain more public discussions, especially the views of students, educators, and policymakers, while industry reports may reveal more detailed practices of AI data governance within universities. Future research can expand data sources to provide a more comprehensive analysis.

This comparative analysis also inevitably touches upon important ethical dimensions surrounding AI technologies in education. While our findings illustrate distinct patterns in media representation across cultural contexts, it is critical to explicitly acknowledge the potential ethical implications of AI-driven surveillance and privacy practices in higher education. Technologies such as facial recognition, automated proctoring, and data analytics inherently raise significant ethical concerns, including issues of consent, potential biases, fairness, and the potential misuse or overreach of surveillance tools. Our intention is not to legitimize specific narratives promoted by governments or commercial entities, but rather to highlight how different media ecologies reflect varied ethical frameworks and societal priorities. Ultimately, a deeper ethical engagement with these technologies remains essential for fostering responsible and fair implementation of AI in educational contexts.

6.3. Directions for Future Research