Learning disruptions related to COVID-19 were a catalyst to spotlight the inequities and disparities in educational opportunities and learning (

Vestal, 2021). This served as a call to action for education leaders and teacher educators to respond with innovative, socially just solutions rooted in democratic, economic, and equity imperatives (

House Education and the Workforce, 2024). This systemic change requires a new model for the educator workforce. To do this, we must consider who is included as an educator (e.g., teachers, specialists, paraprofessionals, community educators), as well as the structures that shape the way in which they work together to meet the needs of students. Revolutionizing the workforce moves traditional educational systems where each teacher takes responsibility for the myriad learning needs for each student in their class (i.e., one teacher—one classroom) to an approach that reframes, rather than diminishes, individual educators’ agency. In this new model, educators with distributed expertise work as teams (i.e., strategic staffing;

Basile, 2022) to enhance educational and professional experiences. What is required, then, is a transformation in educator preparation to prepare educators for a new workforce.

Though COVID-19 served as a catalyst, the unexpected nature and magnitude of educational disparities did not subside when the pandemic itself did. While we observed increasing academic achievement gaps between subgroups of students in reading and math (

Lake & Pillow, 2022) and increasing student mental health needs (

Abramson, 2022;

Li, 2022;

Racine et al., 2022), the number of educators in the workforce was declining. This decline arose from continued high rates of educator attrition rates and decreased enrollment in traditional educator preparation programs (

U.S. Department of Education, 2023) resulting in fewer well-prepared teachers. Thus, educator preparation programs must work alongside educational leaders to transform the design of the workforce to one that ensures educators and students alike can thrive.

Teacher educators must respond with a readiness to transform the ways in which early career educators are prepared to work together. However, while education systems have advanced, educator preparation has only changed incrementally in recent decades (

Hood et al., 2022). Knowing the importance of a well prepared education workforce, as well as the ever-evolving nature of education systems, teacher educators who are engaged in preparing the next generation of educators must ask hard questions, set aside traditional mindsets, and critically examine the effectiveness of systems, processes, and practices currently used to prepare future educators.

The purpose of this paper was to describe the landscape of educator preparation within the current context of teacher recruitment and retention in the United States and the imperative for a new vision for schools, including the role of educator preparation in designing a system to foster inclusive and supportive educational environments. Specifically, it is vital that educator preparation programs be agile enough to effectively respond to the diverse needs of the education field, while also offering innovative solutions to shape the design of the education workforce.

Throughout this paper, we use the term educator preparation to acknowledge and promote the broad range of roles needed to support learning in a wide range of contexts (i.e., formal and informal). We use the term teacher in reference to individuals in traditional PK-12 classroom-based roles. We offer examples of how this new vision for educator preparation is being enacted at MLFC, one of the largest teacher education colleges in the United States. We conclude with the next steps and recommendations for educator preparation programs as we move toward new models of schools.

1. Current Landscape of Teacher Recruitment and Retention in the United States

In the United States, there has long been concern and much discussion about teacher shortages. The current teacher shortage means there are many PK-12 classrooms without a permanent or qualified teacher (

Franco & Patrick, 2023). The magnitude of this concern in the United States cannot be overstated given 3.5 million teachers are needed (

National Center for Education Statistics, 2022). The current teacher attrition rate of 12% also exacerbates the challenge of maintaining a robust educator workforce (

U.S. Department of Education, 2023). For elementary teachers alone, 100,000 teachers on average leave the profession annually (

U.S. Department of Labor, 2025). Teacher shortages vary across the nation (

U.S. Department of Education, 2024). For example, many school systems, particularly those that serve economically disadvantaged communities, have great difficulty attracting and retaining qualified teachers (

Schmitt & deCourcy, 2022). This has important equity implications as students in these communities are more likely to have classrooms filled with underprepared teachers or teachers who lack cultural competence; therefore, these students are more likely to experience learning disruption due to changing, underprepared, or missing teachers (

Gershenson et al., 2021;

Redding & Nguyen, 2020).

Teachers widely express greater dissatisfaction with their jobs, and higher levels of burnout, than ever before (

Barnum, 2023;

Diliberti & Schwartz, 2022;

Kurtz, 2022). In Arizona alone, there were 7518 open positions and 5288 hires made for the 2023–2024 school year. Of those openings, 30% (

n = 2229) remained unfilled, and 76% (

n = 3997) were filled with teachers who did not meet the state’s certification requirements at the start of the school year (

Arizona School Personnel Administrators Association, 2024). Further, by September 2023, 583 teachers had already abandoned their classrooms (

Arizona School Personnel Administrators Association, 2024). Yet, the enormous challenges of recruiting, preparing, and retaining a well-qualified teacher workforce is not unique to individual states or to the United States. Countries across the globe are also experiencing teacher shortages (

Jacobs et al., 2021). For instance, the employment forecast in Morocco indicated the need for approximately 20,000 new qualified teachers annually to maintain their teacher workforce (

Chami, 2018). In the Netherlands, a recent Ministry of Education report indicated an average of nearly 10% unfilled primary school positions (

OCW, 2022). In fact,

UNESCO (

2024) announced a global teacher shortage crisis with a predicted 44 million teachers needed for universal basic education by 2030, with the greatest needs in sub-Saharan Africa.

A factor in the teacher shortage challenge is the public conversation about the profession. The public discussion often focuses on the lack of attractiveness of the profession and the difficulties encountered by teachers such as the limited resources, non-competitive pay, demands and stress of the profession, isolation of the work, and lack of administrative support (

Johnson & Birkeland, 2003;

Kraft & Lyon, 2024;

Schmitt & deCourcy, 2022;

UNESCO, 2024). For example, public discourse highlights that teachers are often asked to manage a large number of students; be role models and social workers; be data analysts, serve as trauma interventionists, and serve in a host of other roles. These narratives contribute to eroding public support for the profession, particularly by parents of school-aged students. For instance, 62% of respondents indicated that they would not “like a child of [theirs] to become a public school teacher in [their] community” (

Phi Delta Kappan, 2022). The negative public perception of the attractiveness of the profession is exacerbated by a common classroom structure that has remained virtually unchanged since the beginning of public education in the United States—the one-teacher, one-classroom model of schooling where teachers are expected to “provide multiple approaches to learning for each student” (

Council of Chief State School Officers, 2013, p. 4).

Teacher educators recognize the need for personalized learning for students (

Hughey, 2020); however, we do not have the workforce organized to deliver it well. The one-teacher, one-classroom model places unreasonably high expectations on individual teachers to be content and pedagogical experts across all domains, while also attending to the social–emotional and physical development of students (

Basile, 2022). Addressing this challenge requires reimagining the structure and support systems of the education workforce to build public confidence in sustainable and equitable education systems.

2. Discovering Opportunities for Change in Educator Preparation

Given the current landscape of teacher recruitment and retention, now is the time to think differently about the systems in which educators work. As one of the largest colleges of education and the most innovative public university (

U.S. News & World Report, 2023), Leaders, staff, and faculty at MLFC feel a sense of obligation to advance research and discovery of public value for the communities we serve (ASU Charter, 2021). Further, we believe the public’s confidence and support for the education workforce is fundamental to the health of society.

As of 2024, Mary Lou Fulton College for Teaching and Learning Innovations’ (MLFC) current enrollment for teacher certification falls just below 2500 students (

ASU Data Warehouse, 2025) and the school engages with a wide variety of community partners. Given the size of its student body and breadth of its scope of commitment and service, MLFC is well situated to lead innovations in education and educator preparation. Therefore, in 2018, MLFC embarked on an ambitious educator preparation redesign initiative for traditional undergraduate and alternative certification graduate pathways.

Central to MLFC’s redesign is the belief that educator preparation programs must pursue a mission that extends beyond merely credentialing graduates. Educator preparation programs must address an education system that fails to retain or empower teachers and does not produce satisfactory or equitable learning outcomes for PK-12 students. To achieve the goal of aligning educator preparation with

Arizona State University’s (

n.d.) (ASU) commitment to inclusive excellence—taking responsibility for the well-being of the communities we support—we aimed to develop pathways that prepare graduates to thrive as educators in schools and communities. Therefore, in this redesign process, we sought to fully understand the challenges facing future teachers, educator preparation programs, and the future of education systems in order to design innovative and sustainable solutions.

3. Designing a New Vision for Educator Preparation

MLFC’s leadership recognized the need for a highly participatory approach to the redesign process. To do this, they engaged a wide variety of stakeholders, each bringing their unique experiences and perspectives to collaboratively identify key challenges in preparing future teachers. As faculty, staff, and administrators at MLFC embarked on the college’s redesign of educator preparation programs, it was essential to first identify challenges and opportunities within the existing structure.

Though informal discussions and wonderings about how to improve our educator preparation programs had been happening for years, the first official gathering of key collaborators happened during the summer of 2018. At that time, representatives from the faculty, as well as MLFC staff who routinely engage with students came together to create a vision for MLFC’s educator preparation pathways. This phase focused on understanding the challenges in preparing future teachers with an emphasis on developing a deep appreciation for student experiences, including potential barriers to success.

During this discovery phase, a key consideration that came to light was students enter MLFC with a wide variety of skills, experiences, and interests. However, MLFC’s educator preparation programs lacked flexibility to address the diverse skills, experience and interests of students. The field of educator preparation has historically defaulted to a status quo that moves groups of students in lockstep toward a credential (

Wolfensberger, 2015). It became apparent that MLFC’s educator preparation program needed to be designed to keep the strengths and needs of students at the center of all decision making. For example, some students needed or wanted additional time to complete coursework due to personal obligations and/or desired to spend more time engaging with course content or pursue a specialization.

Further, traditional programs prepare educators to work in classrooms alone, thus perpetuating the one-teacher, one-classroom model (

Little, 1990) assuming each teacher enters the classroom with the exact same skill sets. This long-standing model for school systems produces neither the learning outcomes nor the professional satisfaction desired. Lack of professional satisfaction contributes to challenges with retention, while also diminishing the perception of the educator workforce and contributing to difficulty with recruitment. Therefore, we saw the urgent need to consider how teaching and learning systems may evolve to foster increasingly inclusive environments. With this in mind, we set forth to design pathways which prepare future teachers to work in teams and be able to adapt to uncertain circumstances.

Redesigning educator preparation to emphasize collaboration and distributed expertise requires careful consideration of the potential shifts in power dynamics within schools. A shift towards teaching on a team may raise concerns about perceived loss of autonomy or control, but it is crucial to address these concerns by emphasizing that team teaching is not about diminishing individual teacher agency, but rather about leveraging individual strengths within a collaborative framework. This model empowers teachers to specialize and share responsibility for a wide range of learners. Existing educator perceptions and the need for cultural change must also be addressed, including concerns about veteran educators’ skepticism towards team teaching and the need for open communication, ongoing support, and opportunities for shared decision making.

In the following sections, we outline the visioning and design process essential to fully redesigning educator preparation in MLFC for elementary education, early childhood education, elementary multilingual education, and special education pathways. Further, we describe the initiatives embedded within the redesign which authentically emerged in response to the challenges present and the aforementioned guiding questions. Though each of these components of change are valuable on their own, we found the greatest impact when changes were made in coordination across the components of curriculum, content, choice, and student support.

3.1. Structuring the Curriculum

As part of this visioning process, faculty identified the knowledge, skills, and dispositions desired in teachers as they enter the workforce, recognizing that novice teachers should not be expected to have the same depth of knowledge and skills as their veteran counterparts (

Andrews & Quinn, 2004). Through a series of design sessions, we curated a list of all the competencies needed for a novice teacher to be effective. As a part of this process, we explored how to organize those competencies to be meaningfully scaffolded over the duration of an educator preparation program.

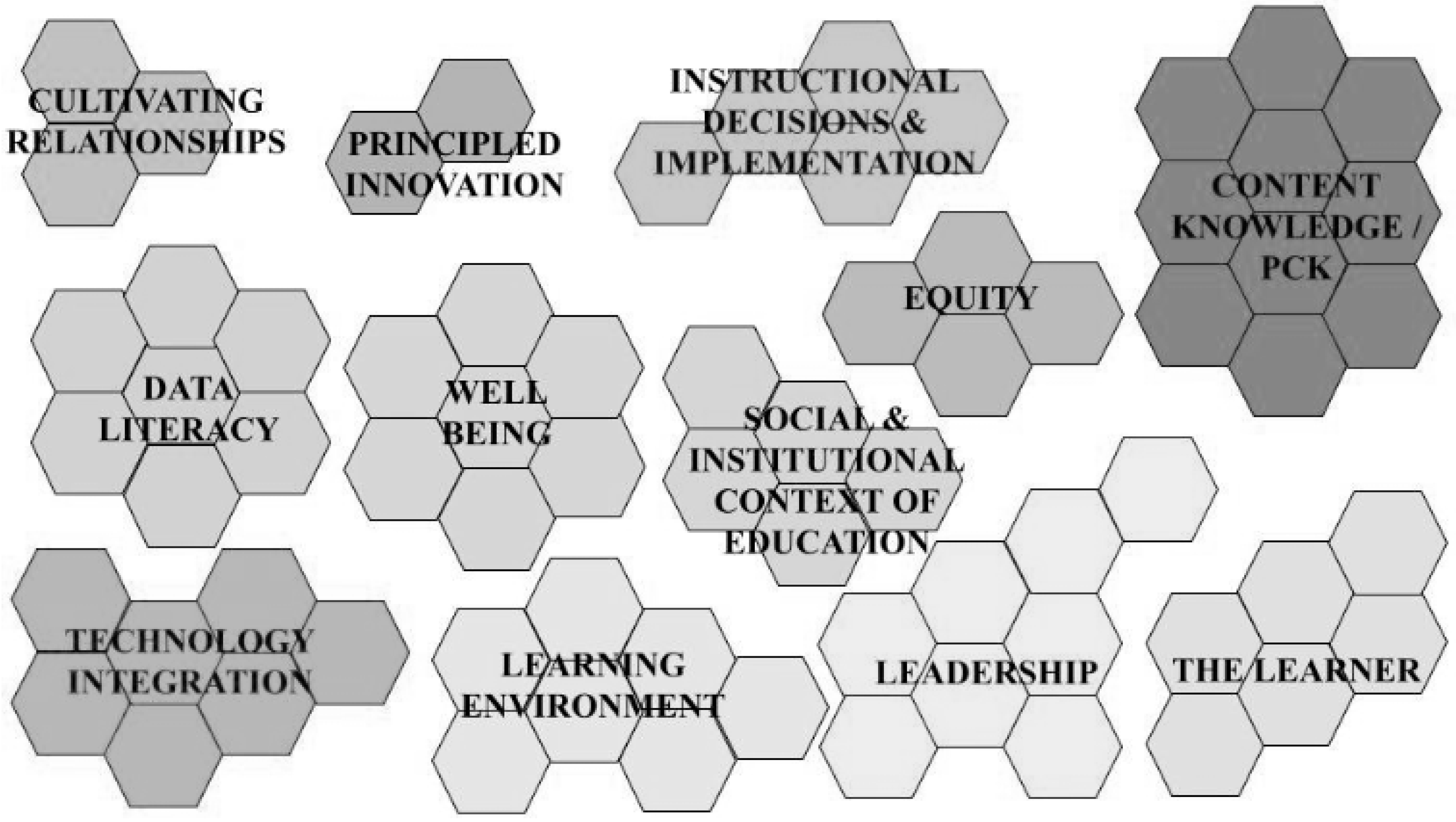

Early iterations of this process included identifying relationships between competencies, as well as cross-cutting themes. We engaged in rich, interactive discussions about how to illustrate these relationships and visualize how knowledge and skills develop over time. For example, one early visual included placing competencies on hexagons and clustering those competencies using the edges of the hexagon to show how competencies related to one another as depicted in

Figure 1 (

Chami, 2018). Hexagons, or hexes, are an “independent group of skills relevant to those working in formal or informal educational settings” (

Maddin, 2018). Examples of hexes include digital citizenship, knowledge of teaching content, and communicating high expectations. Clusters are a “family of hexes grouped together to provide a framework for organizing core principles for the sake of student knowledge and progress” (

Maddin, 2018). Examples of clusters include data literacy, well-being, and education systems. This visual representation was used to demonstrate the relationship between skills and promote consideration of how those skills should be scaffolded and integrated across an educator preparation program. During these early phases, we also experimented with using color saturation in visuals to demonstrate the degree of emphasis on a particular competency. We were intentional in dedicating ample time to these early discussions, acknowledging that this process would include numerous iterations of competencies.

After several initial iterations of preservice teacher competencies, collaborators in the redesign process created Program Level Outcomes (PLOs) for graduates of MLFC’s educator preparation programs. The PLOs were informed by educator preparation standards set by professional organizations such as the Interstate Teacher Assessment and Support Consortium (InTASC), the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE), and the Council for Exceptional Children (CEC;

Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, 2021). PLOs were organized into three domains: (a) Education Design and Decision Making (DDM), (b) Professional Growth, Leadership, Advocacy, and Ethics (GLAE), and (c) Educator Scholar (ES) for undergraduates and Educator Scholar and Integrative Knowledge (ESK) for graduate students.

Designing and organizing PLOs was essential, as the PLOs and associated progression indicators (i.e., introduced, reinforced, and assessed [for mastery]) were used extensively in the curriculum development for the redesigned educator preparation programs. PLOs served as the basis for creating student learning outcomes (SLOs) for individual courses, identifying how skills would be scaffolded over the course of the full program, and designing performance criteria for formative and summative assessments (

Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College, 2021). SLOs, PLOs, and assessment information by course are collected in a central database. At the end of each semester, student performance data by PLO is extracted for real-time analysis to support ongoing program improvement.

3.2. Liberating Content

A core aspect of MLFC’s transformation involved liberating the content by removing barriers and constraints to create inclusive systems and environments for learners. Liberated content are learning experiences which are not constrained by enrollment in a program, access to a specific physical environment, time-bound, or otherwise inaccessible to learners. A high-priority was to develop a system that supported student success by providing opportunities for choice and greater flexibility—while retaining a commitment to quality. Historically, educator preparation programs have relied on a highly structured system in which students move through a predetermined program in unison (

Tom, 1997) with a focus on meeting the requirements of teacher certification. This inflexible system often discourages students from traditionally underrepresented groups (e.g., parents, first generation college students, students from low socioeconomic situations, minority groups) from entering the profession. This is in stark contrast to ASU’s mission and does not align to the needs of its student body. ASU has a high number of PELL grant recipients (

Arizona Board of Regents, 2021), prides itself on the number of first-generation students (

Hinz, 2022b), and has recently been acknowledged as a Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI;

Hinz, 2022a).

In the revised pathways, students engaged in a semester-long student teaching experience, instead of a year-long residency. This change was strategic and grounded in the equity imperative with the aim of offering more flexibility to students and recognizing that factors outside of school (e.g., family and/or work responsibilities) may limit the amount of time an educator preparation student can commit to student teaching. Moreover, we reconceptualized how we acknowledge professional experiences throughout educator preparation programs that honor students’ experiences in pre-professional roles (e.g., paraprofessionals, teacher aides) and build upon those experiences by supporting application of new learning.

Students also have the ability to accelerate and decelerate their pace in ways that best meet their needs. Flexible pathways, such as accelerated educator preparation programs with shorter course terms (i.e., 7.5-week courses), summer coursework, and multiple start dates, are more efficient for adult learners than traditionally designed programs (

Sheffer et al., 2020). Flexible pathways also allow students to pursue specializations that meet their interests and career aspirations.

Additionally, courses are offered in more modalities than ever before. MLFC’s redesigned educator preparation programs are offered in-person on multiple campuses, as well as in two different remote formats: an asynchronous format called ASU online and a synchronous format called ASU Sync in which students take classes via Zoom at regularly scheduled times and interact in real-time with faculty and peers. This format flexibility is designed to allow MLFC to reach more potential teachers including those who reside in remote rural areas. The overall goal in offering flexibility in the delivery mechanisms was to not let barriers related to time and space discourage current or potential students from joining the education workforce.

Milman et al. (

2020) noted that course modality flexibility reduces competition with existing obligations.

MLFC’s choice to modify course pace, frequency, and schedules were designed to increase student retention, persistence, and overall academic success. This approach aligns with MLFC’s commitment to equitable education opportunity, ensuring expanded access for aspiring teachers from diverse backgrounds to successfully gain the skills and disposition to contribute to their communities, regardless of circumstance.

3.3. Learner-Centered Choices

In addition to liberating the content and increasing the flexibility of the structure, we were intentional in incorporating meaningful student choice into the educator preparation programs. To create space and a systematic method for coursework choices, we designed six categories of courses that constitute each of the undergraduate educator preparation programs (

Table 1) as a mechanism to identify opportunities to offer choice. Within the undergraduate sequence, all prospective educators, regardless of their chosen pathway (e.g., special education, elementary education) take identical Foundational and Pedagogical Core courses together. These shared courses are designed to provide future educators with a shared knowledge when transitioning to the education workforce, with some differentiated instruction and assignments in the pedagogical courses based on respective pathways. The Professional Core and Professional Experience courses are tailored according to the chosen educator pathway, while Specialization courses offer flexibility based on individual interests and career aspirations. Collectively, these six course categories provide students with a comprehensive and diverse range of learning experiences. An example of how the six course categories align in the elementary educator preparation program can be found below (

Table 1).

3.4. Specialized Learning and Support

Further, there is a need for students to develop specialization to diversify the knowledge and skill base of the education workforce. Given the rapid pace of change in education systems across the globe, it is necessary to prepare educators to collaborate in order to draw upon the variety of skill sets that can be established through specialization coursework. MLFC’s approach to educator preparation is driven by an understanding that learners are not identical. They enter their programs with a unique set of skills, experiences, and interests. It follows, then, that educators should not be expected to have an identical skills set either. Learner-centered education requires specialization. In addition to taking classes in the Foundational, Pedagogical Core, and Professional Core courses, students have access to specializations through electives. Specializations are personal interest areas that students can select from, or if desired, a student can customize their own. Some specializations address content and others address pedagogy. Examples of specialization areas, comprising 9 to 12 credits of coursework, include student welfare and advocacy, counseling, leadership, civic engagement, global studies, family and human development, and sustainability. Should a student have an interest in an area beyond the specializations that are defined, they meet with an academic advisor and a career coach to outline an individual area of interest.

By supporting future educators in developing expertise in a specialized area, MLFC is supporting the development of teams of educators with distributed expertise. These teams of educators will have a distinct advantage when education systems need to quickly adapt to the changing world, as they will be prepared to draw upon each other’s strengths, thus enhancing student achievement. Further, this level of personalization—or learner-centeredness—also sets a standard we hope our graduates take with them as they become educators.

MLFC also recognized the ways in which we support future educators to enter a rapidly changing profession needed to evolve. To accomplish this, MLFC’s student support services office revised the way in which student services operated to meet the current realities for preservice teachers. Given MLFC’s focus on the student experience, it was essential to collaborate across all departments that impact the student experience, regardless of their status as an academic or support department. This culture of deep collaboration was central to implementing sustainable change. MLFC now offers holistic guidance through student success coaches who assist with academics, career planning, financial literacy, and wellness. Given our mission to liberate content, updates to student support also enable personalized support regardless of the student’s location.

Table 2 summarizes key shifts in educator preparation at MLFTC, showing the movement from traditional models (“from”) to more flexible, inclusive, and student-centered approaches (“to”) across four categories.

4. Membership in Professional Communities

Historically, teaching has been an independent and at times isolating career path (

Little, 1990). Through redesigning educator preparation programs, MLFC has designed opportunities for future teachers to collaborate during pre-service training with the goal of supporting preservice teachers in developing collaboration skills, as well as a disposition for collaboration. In addition to structuring educator preparation programs to support collaboration between students, the structures in which faculty members work were also transformed to support faculty collaboration. For instance, traditional course syllabi had been developed by a single faculty member with expertise and experience in a content area relevant to the course. When creating the syllabi and related content for courses during this redesign process, faculty worked in teams with distributed expertise. Most teams included between two and six core members who were responsible for seeing the course through the full development and approval process. Additional faculty members engaged with the team as thought partners in the process. Further, the leadership structure for the MLFC was revised to ensure diverse perspectives and skills were included in guiding the pathways. For example, the individuals responsible for leading specific programs, sometimes called program chairs, changed from an individual person to a team of two people and finally a team of three.

4.1. Professional Educator Series

Fostering a professional mindset for students to see themselves as scholars and part of a larger scholar community in which they learn from one another to offer the best possible educational opportunities to students was a key goal when redesigning MLFC’s educator preparation programs. Therefore, MLFC designed a series of Professional Educator courses. This eight course one-credit series is part of the pedagogical core. In the Professional Educator Series, future teachers will explore a variety of topics through seminars, learning labs, and modules that scaffolded their understanding of teaching and learning topics covered each term in their other courses and professional experiences. Throughout the course series, students reflect on core themes in the MLFC experience (e.g., principled innovation, personal and meaningful learning, teaming). See

Table 3 below.

4.2. Professional Experiences

Participating in experiences in educational settings provides an opportunity for students to meaningfully engage with professionals and start to see themselves as members of the educator workforce. When redesigning MLFC’s educator preparation course, faculty members were inspired to include more professional experiences and to start them earlier in a student’s college career (

Darling-Hammond & Bransford, 2007). In this way, students can explore the profession early and often. Allowing them ample opportunities to build relationships with professionals and apply their developing skills in authentic settings. Undergraduate students start their field experiences in their third semester and increase their hours and responsibilities throughout the pathways’ sequence, culminating in their full-time student teaching experience in the eighth semester. Graduate students on an alternative certification pathway begin their professional experiences during their first semester of graduate studies.

Despite the many benefits of engaging in professional experiences, MLFC faculty also acknowledged a student’s professional experience has the potential to be discouraging if the student does not feel as though they have the proper support. To remedy this, MLFC offers holistic support through personalized coaching and assistance to all our students, even students who are taking remote classes and are participating in internships and student teaching far from any of our campuses. The first iteration of the redesigned educator preparation programs kept the structure of the upper division experiences in a traditional format, whereby students took Professional Core and Pedagogical Core courses and had a separate professional experience course alongside. The second and most current iteration revised this traditional structure and created clinically embedded courses. Rather than having stand-alone internship courses, one course taken in each of terms five, six, and seven was revised from three credits to four credits; and the internship hours that have previously been in separate courses were embedded in those courses. This allows faculty members to provide students with feedback on content knowledge, general pedagogy, and pedagogical content knowledge and application in a cohesive manner. The aforementioned change to combining a course with a professional experience increased the connection between content and practice for students and provides a more integrated and effective educational experience.

5. A New Vision for Schools

Reconceptualizing educator preparation requires a new vision for educational systems that prioritize the health and well-being of students, teachers, school staff, families, and communities. This new vision, modeled by MLFC’s Next Education Workforce is defined by the use strategic staffing models which place educators with distributed expertise on teams, draw upon the strengths and resources in the community, and develop career advancement pathways for educators with the goal of providing personalized learning to students and empowering teachers. Strategic staffing offers new ways to shift the conversation about teacher shortages.

Discussions of teacher shortages often fail to acknowledge the real issue—professional jobs that are not sustainable for teachers (

Basile, 2022). Given the rate at which people are leaving education jobs, eroding public opinion, and decreasing enrollment in traditional teacher preparation, it is essential to address important retention factors. The education system must be designed to give people reasons to stay in the profession to increase the likelihood that educators will be effective, satisfied, and enjoy the rewards that come with collaboration, specialization, and advancement, ultimately leading to improved student outcomes.

Preparing teachers to enter a new and evolving professional teaching environment is an important initiative at MLFC. This mission is central to MLFC’s Next Education Workforce which collaborates with schools and other partners to (a) provide all students with deeper and personalized learning by building teams of educators with distributed expertise and (b) empower educators by developing better ways to enter the profession, specialize and advance (

Basile, 2022). Initiatives like the Next Education Workforce, showcase how MLFC is committed to supporting local education systems through innovation in how teachers are deployed and utilized in strategic staffing models.

MLFC’s Next Education Workforce initiative works to deepen the relationships between schools and the communities in which they operate. One key way to achieve that goal is to provide opportunities for community members with skills to take their knowledge and compassion into the classroom. At MLFC, we have developed online nanocourses accessible to the community through the Community Education Learning Hub. These nanocourses help build skills that support community members in becoming valued members of education teams.

By building teams of educators with distributed expertise, opportunities for career growth abound. Educators have an incentive to pursue deeper learning in areas of interest to better serve their team. Additionally, educators, especially veterans, have opportunities to develop their leadership skills and take on new leadership roles in the team (e.g., lead teacher).

To be responsive to the diverse needs of our partners in education systems, it is important that educator preparation programs establish systems that amplify our knowledge and understanding of our students, community partners, and policy landscapes (

Grossman & Fraefel, 2024). For example, at MLFC, we use common assessment, end-of-program surveys, and course feedback loops embedded to better understand the experiences and needs of our students, in real time, so that we can adjust to meet the unique needs of each student and cohort. Additionally, we regularly engage in structured partnerships through initiatives like the Community Design Labs and feedback sessions with school districts and educators to ensure we have a comprehensive understanding of the evolving needs of our community partners (

Basile, 2022).

6. Recommendations

The challenges and innovations illustrated above were the products of a lengthy effort. The process of fully redesigning how MLFC’s faculty and staff prepare future educators was extensive and spanned over more than six years. As a result of this process, we gained insight into new ways of approaching educator preparation. With these new insights in mind, we have developed suggestions for enhancing systems and approaches to preparing educators and engaging with the education workforce.

Structuring the curriculum to address students holistically, including valuing their previous experiences and interests, as well as acknowledging that it will take beyond four years to master the skills of a veteran teacher, is a vital component to shaping a new direction for educator preparation. Therefore, developing PLOs which help to prioritize and organize educator competencies in a way that is useful in planning and organizing curriculum is an essential component of creating educator preparation programs that honor students’ experiences, while encouraging them to develop the disposition and skills for continuous learning.

Liberating educator preparation content by reducing barriers to access for any individual interested in growing their teaching skills is essential for building a robust and diverse educator workforce. To liberate the content, barriers of time and location should be considered and potentially addressed through offering choice in modality. Additionally, options such as job-embedded assignments or access to curriculum for community-based educators (e.g., tutors, volunteers, mentors) are instrumental in widening access to important learning opportunities.

Placing the learner at the center of decision making is key in empowering learners to develop learner agency. This can be accomplished by offering flexibility, such as options for students to accelerate or decelerate the pace at which they take courses, choice in specialization, and the opportunity to take elective courses. Further, learners should be guided to consider and evaluate their choices, reflecting on what is best for them as a learner.

Becoming aware of, and working to address, the challenges future educators may encounter both within and outside of their coursework is an essential aspect of educator preparation and long-term teacher well-being. A robust and agile system for providing holistic support and guidance for students may include a suite of coaches ready to assist with academics, career planning, financial literacy, and wellness. Creating a sustainable teaching workforce begins with recognizing that the skills and tools teachers use to support themselves are equally as important as the pedagogical knowledge they gain during their preparation.

Identifying as a member of the education profession is an important step for students in educator preparation programs, for it empowers them to identify not just as teachers but as leaders, innovators, and advocates for systemic change. By embracing these roles, future educators are better equipped and empowered to navigate the complexities of modern education. Intentionally starting professional experiences early in educator preparation programs and including course content dedicated to issues permanent to the profession can enhance future educators’ perception of themselves as members of the profession.

Recognizing the need for teams with distributed expertise is important in shifting the perception of teaching as an isolated job to seeing teaching as an opportunity to contribute to a network of teachers with the aim of supporting students, families, and communities. Deploying future educators in a team during their professional experience is a key step in developing their collaboration skills while simultaneously embedding opportunities for joint learning and co-reflection. Further, this serves as a model for schools to strategically consider staff to leverage expertise and resources.

Finally, we acknowledge the need for an iterative approach, as educator preparation programs need to be prepared to respond to the changing needs of preservice teachers, PK-12 students, the education workforce, and their greater community. Therefore, we recommend educator preparation programs establish sustainable mechanisms for reviewing, revising, and enhancing their programs using a continuous improvement model. We recommend using a systems-based approach to monitoring and revising educator preparation programs to ensure that programs are designed holistically to meet the needs of all education stakeholders.

7. Conclusions

Though MLFC’s redesigned educator preparation programs have moved from the planning to implementation stage, we acknowledge there is still work to be done. Just as primary and secondary schools are evolving, educator preparation programs also need to be agile and innovative to meet the needs of their students, the teacher workforce, and society. MLFC plans to continue employing a reflective and iterative approach to our work.

Recognizing that educational systems will continue to evolve, the redesign initiatives reviewed in this paper showcase the need for interactive, iterative, and responsive processes to safeguard educator preparation longevity and relevance. Moreover, our redesign further aligns our college with the ASU charter and its commitment to inclusivity, measured not by whom it excludes but by whom it includes and how they succeed. Through our transformations in educator preparation, we are more equipped to empower future educators to address the diverse and ever evolving needs of students, families, and communities.