1. Introduction

Inclusive education (IE), championed by UNESCO, has emerged as a predominant trend in international educational development, which emphasizes that all students with special educational needs have the right to access mainstream schools. Building on these global developments, China has been systematically developing and implementing an indigenized inclusive education model since the Reform and Opening Up policy (

Pang, 2020).

Key Priorities of the Ministry of Education (2021) explicitly state that special education development should adopt progressive inclusion as its core objective in China. These guidelines emphasize three strategic focuses: (a) strengthening service coverage through expanded accessibility, (b) optimizing support systems for resource allocation, and (c) enhancing instructional quality via evidence-based practices (

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, 2021a). The

Third Special Education Enhancement Plan (2021–2025) mandates the strengthening of special education workforce development and systematic implementation of inclusive education (

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, 2021b). As a core manifestation of educational equity, inclusive education advancement constitutes an essential trajectory for China’s special education reform. Furthermore, with the ongoing expansion of inclusive education programs, quality assurance has emerged as the paramount policy priority (

Zhou & Wang, 2022). The availability of qualified educators constitutes a fundamental prerequisite for enhancing instructional quality in inclusive education, as inclusive education specialists are pivotal to ensuring program effectiveness. However, empirical evidence indicates that within mainstream educational settings, burnout levels among inclusion teachers remain significantly higher than those observed in both special education professionals and general classroom educators (

Candeias et al., 2021;

Lavian, 2012). Two predominant mechanisms underlie this phenomenon. First, consistent with established principles of adult developmental psychology, both chronological aging and accumulated teaching experience correlate with progressive decline in professional novelty perception and intrinsic motivation, ultimately culminating in job burnout. Second, the unique characteristics of learners with diverse needs in inclusive settings substantially increase educators’ susceptibility to emotional exhaustion, particularly when supporting students requiring specialized educational interventions. Job burnout detrimentally impacts both educators’ psychological and physiological well-being, manifesting in clinical symptoms including anxiety disorders, depressive episodes, and somatic manifestations such as chronic cephalalgia (

Hu et al., 2015). Furthermore, it undermines educational quality and institutional stability through three primary pathways: reduced pedagogical efficiency, diminished capacity to manage disruptive behaviors, and elevated staff attrition rates (

S. Li et al., 2020). Therefore, to enhance instructional quality in inclusive education and strengthen the professional capacity of practitioners, developing evidence-based interventions targeting occupational burnout among these educators has become a critical imperative.

Burnout among inclusive education teachers is influenced by multiple factors. Extensive research has demonstrated that individual characteristics, particularly years of teaching experience, gender, professional expertise, and competencies in inclusive practices, significantly contribute to this phenomenon (

Busby et al., 2012;

Wei & Yuan, 2000), in addition to other factors. It is also closely related to various aspects such as social support, workload and school climate (

Xie et al., 2021;

M. Liu, 2010). School inclusive climate is one of the extremely important social factors affecting job burnout, which is a relatively stable and lasting climate that gradually develops as a result of the long-term interactions between teachers of inclusive education and the factors in the surrounding environment in the process of teaching and interaction (

Wang et al., 2020).

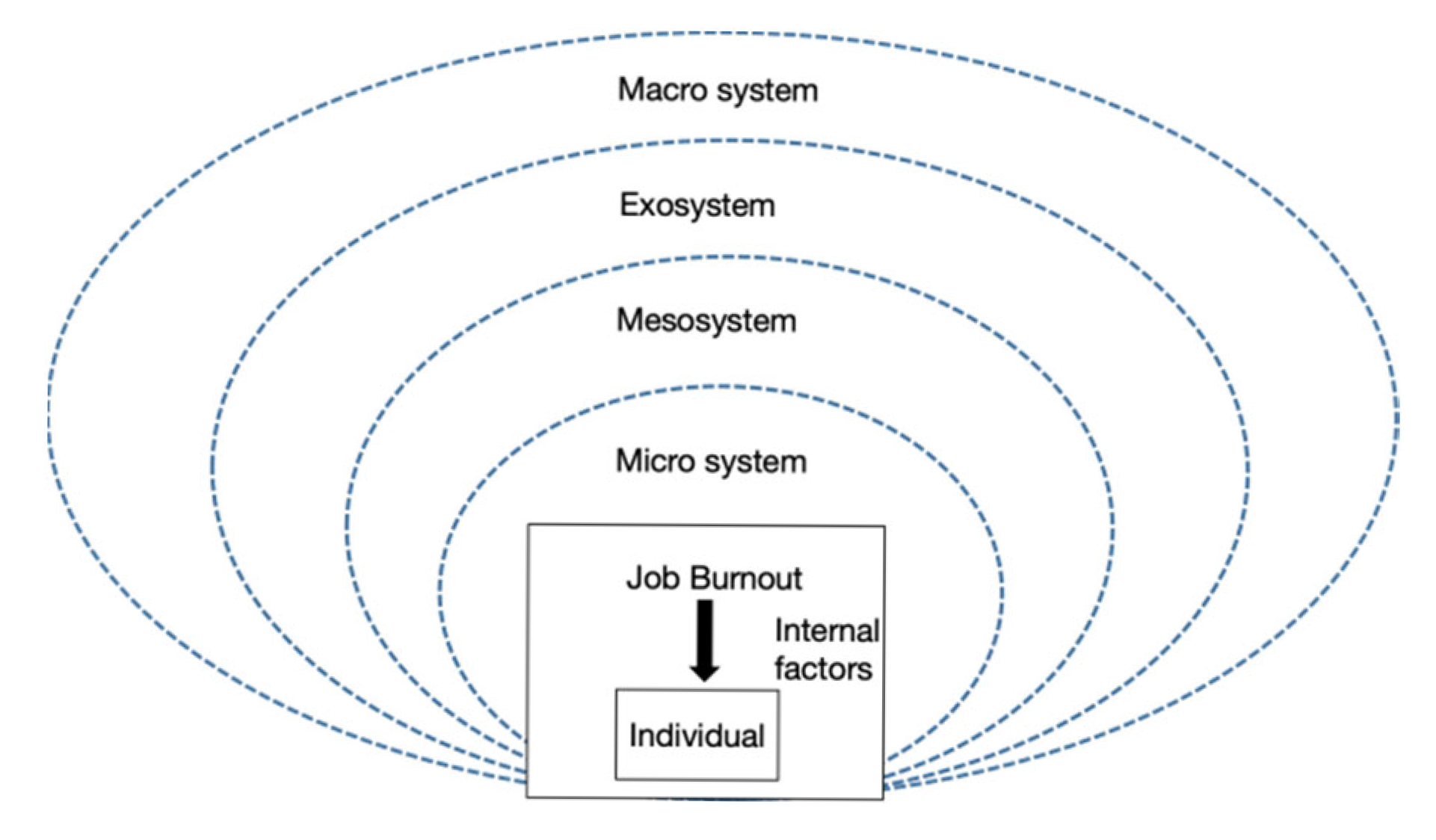

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory posits dynamic reciprocity between individuals and their nested ecological systems in shaping development. This conceptual framework contends that human growth trajectories emerge not merely from individual attributes but through transactional relationships with micro-, meso-, exo-, and macrosystems (

Bronfenbrenner, 1989). The ecological systems theory demonstrates considerable relevance in guiding theoretical research on job burnout among inclusive education teachers, highlighting teachers’ pivotal role within the classroom ecosystem of inclusive education while providing a conceptual foundation for investigating burnout mechanisms. Existing studies indicate that the formation of teacher job burnout exhibits systemic characteristics, arising not from singular causative factors (

Y. Li & Yong, 2010;

Xie et al., 2021;

Zheng, 2013) but, rather, being embedded within a complex ecosystem spanning from micro-level classroom contexts to macro-level societal structures (See

Figure 1). A multi-level analysis through this theoretical lens reveals differentiated intervention pathways: At the microsystem level, optimizing classroom management paradigms, fostering positive teacher–student interactions, and implementing personalized instructional support strategies can effectively mitigate burnout. Within the mesosystem, cultivating inclusive school cultures and enhancing teachers’ decision-making participation strengthens professional belonging and organizational identity. The exosystem level emphasizes deepening home-school collaboration networks and integrating community educational resources to provide external support buffers. At the macrosystem level, implementing teacher workload reduction policies and reconstructing societal expectations can systemically improve professional ecosystems through institutional reforms. This multi-tiered framework underscores that addressing teacher job burnout requires a systemic ‘individual–organization–environment’ co-evolution logic, where coordinated interventions across ecological levels—from classroom practices to policy-making—collectively reshape the professional landscape. The ecological perspective thus offers both theoretical legitimacy and methodological guidance for developing comprehensive strategies to prevent and alleviate job burnout in inclusive education contexts.

In inclusive education, teaching efficacy refers to teachers’ self-assessment, beliefs, and perceptions regarding the value of their work, their capability to deliver inclusive education effectively, and their capacity to foster the development of children with disabilities. This construct reflects teachers’ confidence in their professional abilities (

Zan et al., 2011). Research demonstrates a significant negative correlation between teaching efficacy and job burnout. Teachers’ efficacy influences their emotional resilience and stress management; those with high efficacy exhibit confidence in addressing diverse needs of both general and special education students. Additionally, they believe in the successful integration and effective education of special needs students in mainstream classrooms (

Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998).

Weienfels et al. (

2021) and

Boujut et al. (

2017) argue that higher teaching efficacy enhances self-confidence, enabling teachers to approach their work with greater ease. Reduced psychological pressure and proactive coping strategies further mitigate burnout risks. These findings highlight the critical role of teaching efficacy in reducing burnout. Accordingly, this study hypothesizes a significant negative correlation between teachers’ efficacy and job burnout.

Extensive research confirms the critical role of school climate in shaping teachers’ efficacy. Specifically, a school’s inclusive climate has been shown to correlate positively with teaching efficacy (

Schaefer, 2010). A supportive inclusive climate empowers teachers to engage in professional development. When schools assign clear responsibilities and provide structured opportunities, teachers actively participate in professional learning initiatives (

Krecic & Grmek, 2008).

Wang et al. (

2020) surveyed 1676 primary and secondary inclusive education teachers in China, finding that fostering a positive school integration climate significantly enhances teaching efficacy. School administrators who strongly support inclusive education often provide teachers with financial and material resources (

Weisel, 2006). A positive inclusive environment fosters teachers’ sense of belonging, motivates proactive engagement in professional practices, and improves pedagogical competence (

Hosford & O’Sullivan, 2016). These factors collectively strengthen teachers’ confidence in addressing the needs of students with disabilities (

Wilson et al., 2018;

Soodak et al., 1998). Therefore, cultivating a supportive school inclusive climate is a key strategy for enhancing teaching efficacy. Building on this evidence, the study hypothesizes a significant positive relationship between school inclusive climate and teachers’ efficacy.

In summary, a supportive school inclusive climate reduces job burnout. Therefore, this study addresses three research questions: (1) Is the perceived school inclusive climate correlated with burnout among inclusive education teachers? (2) What mediators explain the relationship between school inclusive climate and teacher burnout? (3) What school-level interventions can effectively reduce burnout in inclusive education settings? Building on this foundation, the study examines the impact of school inclusive climate on burnout and proposes two hypotheses: Hypothesis 1. School inclusive climate directly predicts burnout among inclusive education teachers. Hypothesis 2. School inclusive climate influences burnout through the mediating role of teaching efficacy. By testing these hypotheses, the study aims to identify strategies for reducing teacher burnout, thereby supporting the inclusive education workforce, improving instructional quality, and fostering sustainable growth in this field.

2. Procedures and Methods

2.1. Participants

To ensure the scientific rigor and generalizability of the research sample, this study employed a combined strategy of random sampling and stratified sampling to secure representativeness across spatial distribution, economic levels, and social functionalities, thereby comprehensively reflecting the diversity of the target population. The sampling process adhered to two principles: geographical coverage and population representativeness. First, three representative provinces were selected based on spatial distribution: Beijing (North China/political hub), Shanghai (East China/economic center), and Yunnan (Southwest China/border region). Second, multidimensional differentiations were considered, encompassing north–south regional disparities, economic development gradients (contrasting developed and moderately developed areas), and functional zoning characteristics integrating political and economic centers. A total of 675 questionnaires were collected. Through double-blind coding and validity checks (excluding 62 invalid responses with logical inconsistencies or >15% missing values), 613 valid samples were retained (90.8% validity rate) (see

Table 1). This procedure ensured the sample’s representativeness across spatial heterogeneity, economic gradients, and social functional diversity, satisfying the requirements for scientific validity and population generalizability.

This study sample comprised 613 inclusive education teachers. By gender, the sample included 519 females (84.7%) and 94 males (15.3%). Age distribution was as follows: 132 participants (21.5%) aged 21–30 years, 263 (42.9%) aged 31–40, 188 (30.7%) aged 41–50, and 30 (4.9%) aged 51–60. Teaching experience ranged from 0 to 2 years (n = 58, 9.5%), 3–10 years (n = 166, 27.1%), 11–20 years (n = 293, 47.8%), to ≥21 years (n = 96, 15.6%). Experience in inclusive education included 0–2 years (n = 294, 48.0%), 3–10 years (n = 226, 36.9%), 11–20 years (n = 85, 13.9%), and ≥21 years (n = 8, 1.3%).

While conducting quantitative research, this study also carried out in-depth qualitative interviews. Participants were recruited from Beijing, Yunnan, and Hangzhou—the latter selected for its geographic proximity to Shanghai and similarities in inclusive education development. A stratified purposive sampling strategy was employed to conduct semi-structured interviews with 15 stakeholders: 7 inclusive education teachers, 1 principal overseeing inclusive programs, 3 resource teachers (providing counseling and rehabilitation for students with disabilities), and 4 shadow teachers supporting classroom integration. To ensure confidentiality, all interviews were anonymized using alphanumeric codes.

2.2. Methods

In quantitative research, three validated scales were adopted to measure the target variables, and data were collected through a questionnaire-based survey. Data analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0 and AMOS 22.0, including a common method bias test, correlation analysis, and structural equation modeling (SEM).

In qualitative research, prior to formal interviews with self-constructed teacher interview protocol, researchers introduced themselves to participants, explained the study’s purpose and scope, and assured confidentiality of all shared information. Following informed consent, interview logistics (duration: 30 min; location: private and controlled settings) were mutually agreed upon. To ensure accurate and comprehensive records, participants’ consent for audio recording was explicitly obtained.

2.3. Measures

In quantitative research, the questionnaire comprised four sections.

Section 1 collected demographic data, including teachers’ gender, years of teaching experience, age, and years of service in inclusive education.

Section 2 assessed school inclusive climate using the School Inclusive Climate Scale.

Section 3 measured teachers’ self-efficacy with the Teacher Sense of Efficacy Scale, and

Section 4 evaluated burnout levels through the Job Burnout Scale. The specific contents of the research instruments are as follows:

School Inclusive Climate

The school inclusive climate scale, originally translated by

Schaefer (

2010), was revised and adapted to the context of inclusive education in China, followed by a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). A two-factor measurement model was constructed, with five indicators loaded on ‘Principal support’ and four indicators loaded on ‘School-wide inclusive practices’. The fitting indexes of the modified model were

χ2/

df = 4.601 (

χ2 = 115.021,

df = 25). The model fit reasonably well, with CFI, GFI, AGFI, NFI, IFI, and TLI equal to 0.988, 0.963, 0.933, 0.985, 0.988, and 0.983, respectively; and RMSEA and SRMR equal to 0.072 and 0.020, respectively. The final questionnaire consisted of nine items, measuring two dimensions: principal support and school-wide inclusive practice. The principal supported five items, such as ‘Our principal has rich knowledge of inclusive education’; The school-wide inclusive practice includes four questions such as ‘Our school conducts professional development and other activities to meet the needs of special students to get help from teachers.’ The total scale demonstrated high internal consistency (α = 0.968) and fractional reliability (0.887). The subscales also showed strong internal consistency (α = 0.946 and 0.954) and fractional reliability (0.837 and 0.927). The nine indicators collectively explained 79.895% of the total variance, indicating high reliability and validity. A 5-point Likert scale was used, ranging from ‘strongly disagree = 1’ to ‘strongly agree = 5’, with higher scores reflecting greater agreement and a higher total score indicating a stronger school inclusive climate.

Teachers’ Teaching Efficacy Scale

The teachers’ teaching efficacy scale, developed by

Zhou (

2019), constitutes one dimension of the ‘Teacher Agency in Inclusive Education’ questionnaire. This instrument was revised and adapted to the context of inclusive education in China, followed by a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The final questionnaire comprises seven items, such as ‘I am confident in my ability to implement inclusive education’ and ‘I strive to understand each student’s needs and develop appropriate instructional objectives accordingly’. Factor loadings ranged from 0.61 to 0.81, with subscale internal consistency coefficients (α) between 0.90 and 0.93, split-half reliability coefficients between 0.84 and 0.87. The total scale demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = 0.95) and split-half reliability (0.82), indicating satisfactory reliability for both the total scale and subscales. The structural fit indices were excellent:

χ2/

df = 4.936 (χ2 = 1192.697,

df = 151), CFI = 0.978, GFI = 0.968, AGFI = 0.951, NFI = 0.972, IFI = 0.978, TLI = 0.969, SRMR = 0.033, RMR = 0.024, RMSEA = 0.048, confirming the questionnaire’s strong psychometric properties. Using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘strongly agree’), higher scores reflect greater perceived teaching efficacy.

Job Burnout

The job burnout scale, originally compiled by

Zheng (

2013), was revised and adapted to the context of inclusive education teachers in China, followed by a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). A three-factor measurement model was constructed, with indicators loading on ‘Emotional Exhaustion’, ‘Depersonalization’, and ‘Personal Achievement’. For content validity, this study engaged four inclusive education experts to conduct professional evaluations of the scale items. The content validity index (CVI) reached 0.91, demonstrating strong alignment between the scale items and research objectives. Based on expert feedback, redundant or irrelevant items were removed to refine the measurement tool.

The modified model demonstrated reasonable fit, with χ2/df = 3.216 (χ2 = 347.380, df = 108). The fit indices were GFI = 0.945, AGFI = 0.922, NFI = 0.954, IFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.959, CFI = 0.967, RMSEA = 0.057, SRMR = 0.0513, and RMR = 0.034. The final questionnaire consisted of 16 items, measuring three dimensions: Emotional Exhaustion, Depersonalization, and Personal Achievement. Emotional Exhaustion included items such as ‘I feel exhausted by my work.’ Depersonalization included items such as ‘I feel more distant from my colleagues and students than before.’ Personal Achievement included items such as ‘I have my own work goals and ideals.’ The total scale demonstrated high internal consistency (α = 0.807) and split-half reliability (0.791 and 0.799). The subscales also showed strong measurement characteristics, indicating high reliability and validity. A 4-point Likert scale was used, ranging from ‘strongly disagree = 1’ to ‘strongly agree = 4’, with higher scores reflecting greater agreement and a higher total score indicating higher levels of burnout.

In qualitative research, a semi-structured interview guide, Job Burnout in Inclusive Education Teachers, was developed prior to data collection. Designed as a flexible framework, the guide incorporated role-specific adaptations (e.g., differentiated questions for teachers versus administrators) while allowing iterative refinement of follow-up probes during interviews based on participants’ real-time responses. Thematic exploration focused on three domains: first, perceived interrelationships among school-inclusive climate, teaching efficacy, and burnout; second, teaching efficacy’s hypothesized mediating role; and third stakeholder-generated strategies for burnout mitigation.

3. Analysis

In statistical analysis of this study, SPSS 22.0 was employed to perform a common method bias test, descriptive analysis, and correlation analysis across variables. Structural equation modeling (SEM) using AMOS 24.0 was further applied to examine the mediating role of teachers’ teaching efficacy in the relationship between school inclusive climate and job burnout. Bootstrap resampling (N = 5000) was utilized to validate the mediation effects.

In the interview data analysis of this study, all interview recordings were transcribed verbatim. To enhance efficiency and ensure accuracy, the automated transcription tool IFlytek (a web-based platform for audio-to-text conversion) was utilized. Verbatim transcripts were generated and cross-checked against original recordings and field notes to ensure fidelity. This process yielded over 130,000 words of textual data, which were thematically organized by participant for subsequent analysis. After completing the transcription, the qualitative dataset was processed using NVivo 12s auto-coding function to establish a bridge for analysis with quantitative variables. Following the grounded theory methodology, the interview materials were coded step-by-step through coding and comparative induction. Open coding generated 44 categories, axial coding condensed them into 17 main categories, and selective coding further refined them into 3 core categories.

In addition, the purpose of qualitative research in this study is to refine perspectives or construct theories. When no additional data can be obtained to further develop the characteristics of a certain category, the research information can be considered to have reached theoretical saturation. In this study, when the cumulative number of interviewees reached 13, no new categorical concepts emerged. Additionally, we shared the coding results with an expert in inclusive education, who provided positive feedback, confirming that the collected data had achieved theoretical saturation.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Relationship Between School Inclusive Climate and Job Burnout in Inclusive Education

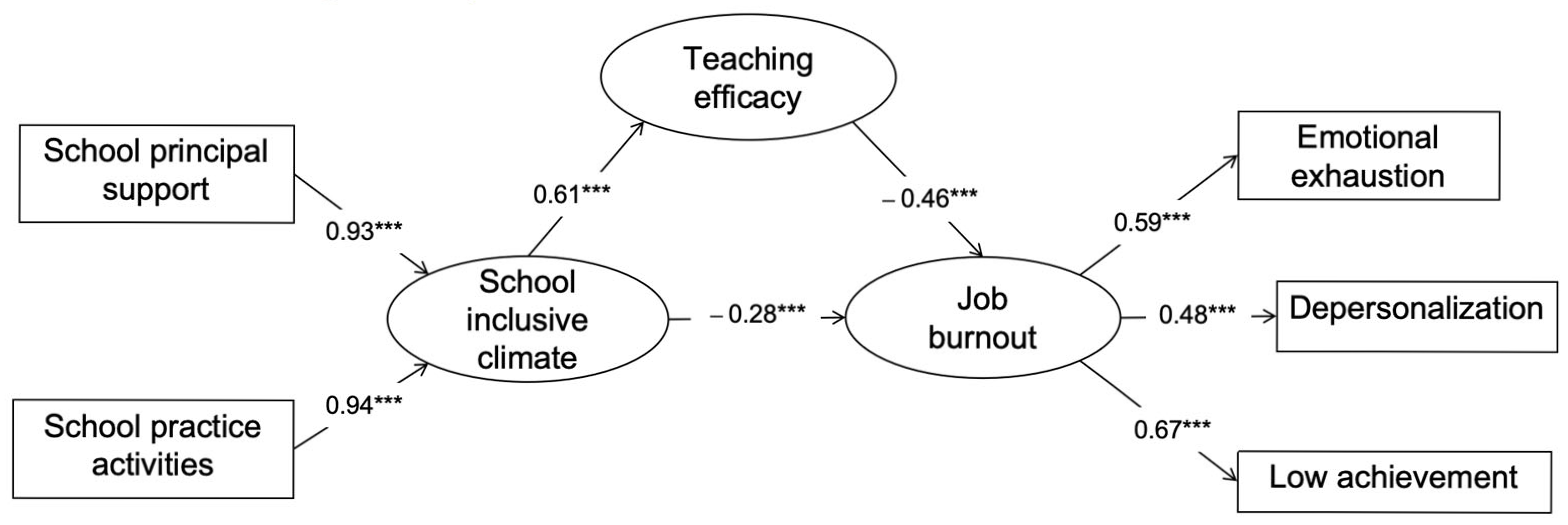

This study explored the relationship between school-inclusive climate and job burnout in inclusive education. Quantitative research results demonstrated a significant negative correlation; i.e., stronger school-inclusive climates were associated with lower burnout levels among teachers.

Freiberg and Stein (

1999) conceptualized school climate as the ‘heart and soul’ of educational institutions—a quality fostering individuals’ sense of value, dignity, and belonging. Schools serve as hubs for teaching and learning, where the environment profoundly shapes daily experiences of teachers and students. A supportive atmosphere enhances perceived self-worth and belonging, thereby mitigating negative emotions (

Fu et al., 2023).

Lavian (

2012) found that unsupportive climates fail to provide resources while imposing excessive responsibilities on teachers. Such conditions exacerbate role ambiguity, stress, and emotional exhaustion, culminating in burnout. Authors have operationalized school-inclusive climate through two dimensions: principal support and inclusive pedagogical practices (

Zhou & Wang, 2022). In positive school-inclusive climates, principals demonstrate robust inclusive education expertise, actively promote its values, and provide structural support for teachers.

Meanwhile, the analysis of interview data revealed a significant negative correlation between the schools’ inclusive climate and teacher burnout. For instance, participant Z05 reported that ‘The instructors at our guidance center systematically demonstrated operational procedures through step-by-step tutorials. This structured approach enhanced my operational competence and consequently reduced psychological stress’. This suggests that when educational institutions implement targeted support mechanisms—including expert mentoring, workshops on inclusive pedagogical practices, and parental recognition of professional efforts—educators experience measurable reductions in occupational strain and corresponding mitigation of burnout symptoms.

5.2. Correlation Analysis Between Teachers’ Teaching Efficacy and Job Burnout

The study revealed a significant negative correlation between teaching efficacy and burnout among inclusive education teachers, indicating that enhancing efficacy reduces burnout risks. Prior research highlights that teacher enthusiasm and responsibility strengthen cognitive, emotional, and behavioral engagement—key protective factors against burnout (

Y. Li & Yong, 2010;

Zhao, 2009).

Bandura (

1982) conceptualized burnout as an efficacy crisis rooted in emotional disengagement.

Ban et al. (

2019) proposed that teachers with higher self-efficacy employ proactive, flexible problem-solving strategies. Such teachers report elevated job satisfaction (

Zhao, 2013) and fewer negative emotions (e.g., anxiety, depression) linked to burnout (

Z. Li & Ren, 2008). Conversely,

Skaalvik and Skaalvik (

2007) found that low efficacy correlates with avoidant coping strategies, exacerbating distress. Strengthening efficacy fosters professional identity and commitment, which collectively reinforce effective teaching practices and buffer against burnout.

Yildirim (

2015) further indicated that efficacy serves as a self-regulatory mechanism for teachers to counteract burnout triggers. High-efficacy teachers exhibit positive attitudes toward students with disabilities, collaborate effectively with peers (

Fu et al., 2023), and actively innovate pedagogy to support student growth (

Weisel, 2006;

Hofman & Kilimo, 2015).

Ban et al. (

2019) surveyed 307 special education teachers, finding that high self-efficacy predicted proactive problem-solving, stakeholder collaboration, and reduced burnout.

In addition, interview analyses revealed an inverse association between teachers’ self-efficacy and job burnout. Participants highlighted that accumulated teaching experience and pedagogical strategies enhanced their capacity to support students with disabilities. This competence fostered strong self-confidence, higher efficacy, and emotional resilience, thereby reducing burnout risks. As participant Y01 emphasized, ‘My 20 years of experience… enable me to confidently address diverse student needs, which sustains my efficacy and minimizes stress’. Collectively, these findings position teaching efficacy as a pivotal lever for mitigating burnout in inclusive education.

5.3. Correlation Analysis Between School Inclusive Climate and Teachers’ Teaching Efficacy

There was a significant positive correlation between school inclusive climate and teachers’ sense of instructional efficacy. Specifically, the more school leaders support and implement integrative practices, the more teachers’ professionalism improves, leading to decreased work stress in a favorable school inclusive climate. Consequently, teachers’ teaching efficacy increases when carrying out relevant teaching tasks, which aligns with the findings of

Zhou and Wang (

2022).

Taylor and Tashakkori (

1995) emphasized that empowering teachers to participate in decision-making and fostering a positive organizational climate enhances both teacher satisfaction and efficacy. Similarly,

X. Li et al. (

2019) found that a positive, harmonious organizational climate, characterized by united and dedicated colleagues, boosts teachers’ enthusiasm and motivation. This supportive atmosphere also encourages joint learning and reflection, thereby enhancing their sense of teaching efficacy.

Moreover, interview analyses revealed a significant positive correlation between school inclusive climate and teachers’ self-efficacy. Targeted supports—such as workshops led by specialists and collaboration with resource teachers—enhanced teachers’ inclusive education competencies, thereby strengthening their pedagogical confidence. Interviewee W02 stated, ‘The school conducted a series of expert lectures, which were very useful to us. We learned theoretical knowledge about integration and how to support children with special needs, unlike before when we found it challenging’.

5.4. School Inclusive Climate Indirectly Influences Inclusive Education Job Burnout Through Teaching Efficacy

Further validation analyses of the study indicated that teacher teaching efficacy played a partial mediating role between school inclusive climate and burnout. Specifically, school inclusive climate can directly affect job burnout and also indirectly influence burnout levels through the mediating role of teaching efficacy. In the positive relationship between school inclusive climate and job burnout, teachers’ teaching efficacy plays a critical role. The process through which school inclusive climate affects job burnout can vary depending on teachers’ teaching efficacy in inclusive education. According to Bronfenbrenner’s ecosystem theory (1989), there is an interaction between the environment and an individual’s cognition, which influences behavior. In other words, schools serve as the primary workplace for teachers, and for the physical and spiritual environment of the school to have a lasting impact, teachers must internalize the environmental influences into a sense of efficacy. This requires teachers to actively adjust their perceptions of the school’s work environment and mobilize their internal ‘energy’.

Qualitative interview data further elucidated the mediating pathway wherein the school’s inclusive climate indirectly mitigates burnout in inclusive education through enhanced teaching efficacy. As Participant L03 articulated, ‘The resource room in our institution enables classroom teachers to conduct curriculum remediation for students with special needs through individualized interventions. These encompass one-on-one implementation of Individualized Education Programs (IEPs), sandplay therapy sessions, and sensory integration training. With the professional collaboration of Ms. Huang, our resource teacher, I have developed greater confidence in scaffolding student development, notwithstanding its incremental nature’. Correspondingly, Participant Z05 emphasized that ‘Parental validation of teaching effectiveness, particularly when accompanied by their adherence to home-based intervention protocols, reinforces my perceived teaching efficacy in inclusive settings. This reciprocal dynamic significantly alleviates work-related strain’.

5.5. Teachers’ Job Burnout Alleviation Through School Climate and Teaching Efficacy in Chinese Inclusive Education Perspective

The Confucian principle of ‘education without discrimination’ in Chinese traditional culture exhibits historical consonance with contemporary inclusive education paradigms. As evidenced by interview data, 78% of participating teachers attributed their enhanced receptiveness toward students with special needs to the professional ethos of ‘educator’s moral consciousness’. This cultural legacy, through its permeation of social values into educational institutions, functions as cultural scaffolding for policy implementation. Furthermore, China’s established legislative frameworks and implementation guidelines systematically support inclusive education development. School administrators’ policy-responsive measures-including fostering inclusive practices, incentivizing pedagogical innovation, and cultivating professional collaboration networks-have effectively empowered teachers with structured instructional autonomy. Thus, to prevent burnout among inclusive education teachers, school leaders should recognize the significant benefits of fostering a positive and supportive school inclusive climate in mitigating job burnout. Additionally, they should acknowledge the mediating role of teaching efficacy in this process. School leaders must take timely and proactive measures to strengthen teachers’ teaching efficacy.

5.6. Additional Variables May Exert Certain Influences on the Study Outcomes

First, the impact of disparities in educational resource allocation on variable relationships manifests in two key dimensions: (1) uneven infrastructure and technological support, where inadequate internet facilities in underdeveloped regions may hinder teachers’ effective resource integration, thereby reducing their sense of teaching efficacy and indirectly exacerbating burnout; (2) regional fiscal investment gaps, evidenced by significantly lower per-student education funding in central/western regions compared to eastern areas, resulting in insufficient work resources (e.g., training opportunities, hardware). When samples cover regions with varying fiscal support levels, the mediating effect of teaching efficacy may demonstrate heterogeneity due to differential resource conditions.

Second, disparities in policy implementation significantly influence the study’s key variables through two primary mechanisms. (1) Policy bias and dynamic resource allocation play a critical role: increased central government transfer payments to central and western regions can enhance teachers’ professional development support, thereby improving teaching efficacy and reducing burnout; however, inadequate policy enforcement may exacerbate perceptions of inequity among educators, undermining intended benefits. (2) Divergent local development strategies create distinct stress patterns: in economically advanced regions, high-performance demands may intensify workload pressure, potentially negating the positive effects of school inclusiveness, while underdeveloped areas face disrupted efficacy-mediating pathways due to resource scarcity.

6. Conclusions

This study yielded three main conclusions: first, there was a significant negative correlation between school inclusive climate and job burnout, indicating that a more inclusive climate was associated with lower burnout levels; second, there was a significant positive correlation between school inclusive climate and teachers’ teaching efficacy, suggesting that a more inclusive climate enhanced teachers’ sense of efficacy; third, school inclusive climate mediated the relationship between job burnout and teachers’ teaching efficacy.

Guided by Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, this study examines the mechanisms through which school inclusive climate influences burnout among elementary inclusive education teachers, with teaching efficacy serving as a critical mediator. It further unravels the nuanced interplay of China’s unique cultural and institutional contexts in shaping these dynamics. The Confucian ethos of educator’s moral authority and benevolence fosters a profound sense of vocational and ethical accountability among teachers, which paradoxically enhances teaching efficacy while simultaneously amplifying emotional labor. Within China’s bureaucratic educational apparatus, collectivist-oriented evaluation systems predispose teachers to internalize burnout as personal inadequacy rather than systemic shortcomings—a stark contrast to Western contexts where educators predominantly attribute burnout to structural constraints (e.g., resource scarcity, policy gaps). This culturally embedded self-accountability, though emblematic of pedagogical devotion, exacerbates psychological strain.

The findings reveal universal patterns of environmental–cultural interplay in burnout development while highlighting context-specific complexities in China. Practically, this necessitates dual-focused interventions: institutional optimization (e.g., decentralizing administrative hierarchies, diversifying evaluation metrics) coupled with cultural recalibration (e.g., reframing professional identity narratives).

8. Limitation

There are still some shortcomings and limitations in this study, which need to be further explored. First, the participants in this study were selected from Beijing, Shanghai, and Yunnan, resulting in regional bias and gender imbalance in the sample, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Future research could expand the sample size and strive to maintain regional and gender balance in sampling to enhance the scientific rigor and validity of the study. Second, this study is grounded in ecosystem theory, focusing on the relationship between the environment and individuals, as well as the mediating role of teachers’ teaching efficacy. However, the literature review reveals that many other factors may also influence teacher burnout, some of which play significant moderating roles. For example, disparities in educational resource allocation and variations in policy implementation can have important effects. Future research could further explore these potential influencing factors. Third, this study adopts a mixed-methods approach, primarily relying on quantitative research supplemented by qualitative analysis. While it examines correlations, it cannot establish causal inferences between variables or fully capture the long-term effects or developmental processes of teacher burnout over time. Future research could employ longitudinal case-tracking studies to explore causal relationships between variables, which would help deepen the understanding of how teacher burnout evolves in response to changes in school inclusive climate and teachers’ teaching efficacy.