Students’ Perceptions of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) Use in Academic Writing in English as a Foreign Language †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review, Theoretical Framework, and Guiding Perspectives

2.1. Academic Dishonesty and Plagiarism

2.2. Academic Dishonesty, Technology, and AI-Related Plagiarism

2.3. Students’ Perceptions of Plagiarism and AI in Academic Dishonesty

2.4. Theoretical Framework and Guiding Perspectives

Transformative learning is learning that transforms problematic frames of reference—sets of fixed assumptions and expectations (habits of mind, meaning perspectives, mindsets)—to make them more inclusive, discriminating, open, reflective, and emotionally able to change. Such frames of reference are better than others because they are more likely to generate beliefs and opinions that will prove more true or justified to guide action.(pp. 58–59)

3. Method

3.1. Aim of Research

- RQ1: How do students perceive the use of generative AI dishonestly in L2 writing, including their definition of it, their views on its negative implications, and the motivations they believe make students use it? This research question and its sub-questions deal with general aspects of students’ perception of the use of generative AI dishonestly in L2 writing, including how they define it, whether they think it is negative, and what they believe motivates students to use it:

- RQ1.1: What definition and examples do students give for academic dishonesty in L2 writing with ChatGPT?

- RQ1.2: What negative consequence of using AI dishonestly in their L2 writing can students identify?

- RQ1.3: What do students believe are their motivations for using AI dishonestly in their L2 writing?

- RQ2: What do students believe about how easy it is to detect AI-generated textual content?

- RQ3: What do students think teachers and institutions should do about AI-based academic dishonesty in writing in terms of response to and prevention of dishonesty?

- RQ4: Do students think it is acceptable to use ChatGPT and similar technologies in their academic writing, and what reasons do they give for using it?

- RQ5: How do students think tools like ChatGPT have already affected academic integrity in writing, and what predictions do they make about future generative AI use in writing?

3.2. Study Design

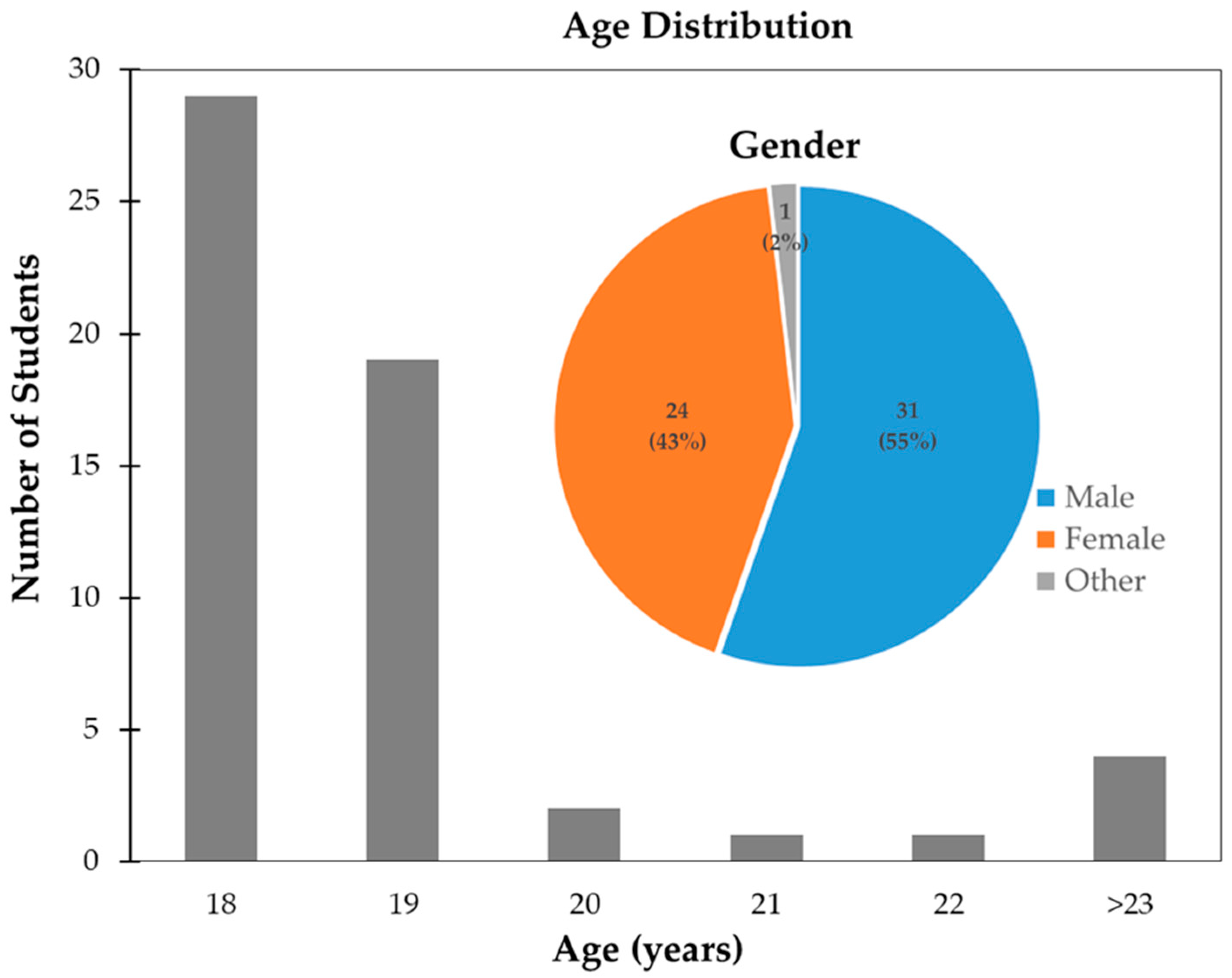

3.2.1. Context and Participants

3.2.2. Data Collection

- ○

- Pseudo-success: Pseudo-success refers to situations in which students appear to achieve academic success (for example, a strong grade on an essay), but they do not meaningfully engage with the materials because they used AI tools to think for them. Said differently, students achieve good grades without truly understanding the material.

- ○

- Dishonest use: Dishonest use is when students plagiarize. They use GenAI to complete assignments and do not report that they used AI to help them (a lack of transparency). Dishonest use is when students misrepresent who authored a written assignment, such as an essay.

- ○

- Ethical AI Practices: Ethical AI practices are the transparent and responsible use of AI in academic contexts. These practices refer to adhering to academic policies and crediting GenAI text (transparency).

- ○

- Raising Awareness: Raising awareness refers to informing students, teachers, and administration about creating original works.

- ○

- Implementing Policies: Implementing policies refers to developing, communicating, and enforcing institutional rules or guidelines related to AI use and academic writing.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. RQ1: Students’ General Perceptions of Generative AI

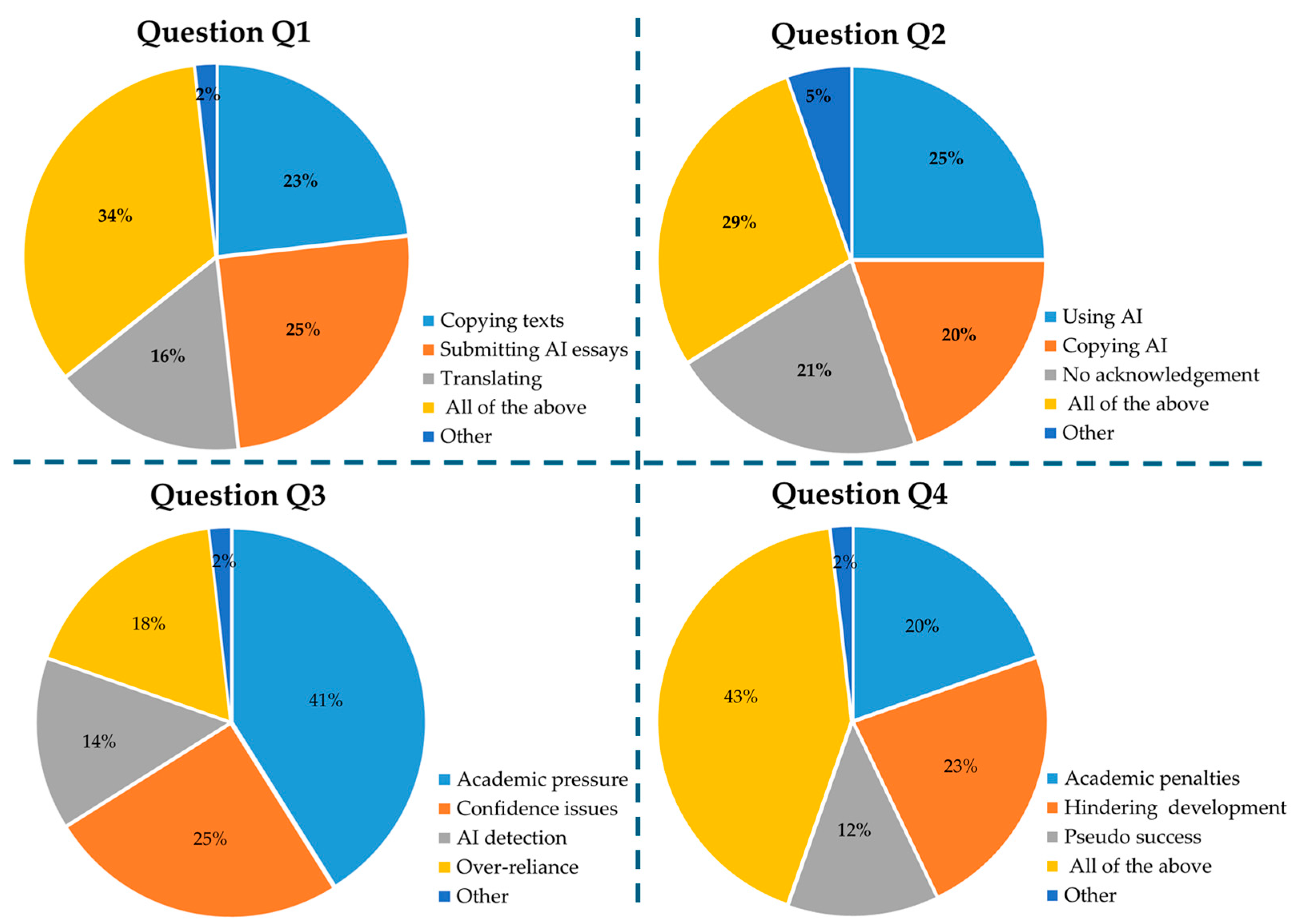

- Q1: How do you define academic dishonesty involving AI technologies like ChatGPT in the context of your writing production?

- Q2: What specific examples can you provide for using AI technologies dishonestly in your writing?

- Q3: What are the main reasons someone might use AI technologies dishonestly in your writing production?

- Q4: What do you believe are the consequences of using AI dishonestly in your writing?

4.1.1. Q1: Main Findings

4.1.2. Q2: Main Findings

4.1.3. Q3: Main Findings

4.1.4. Q4: Main Findings

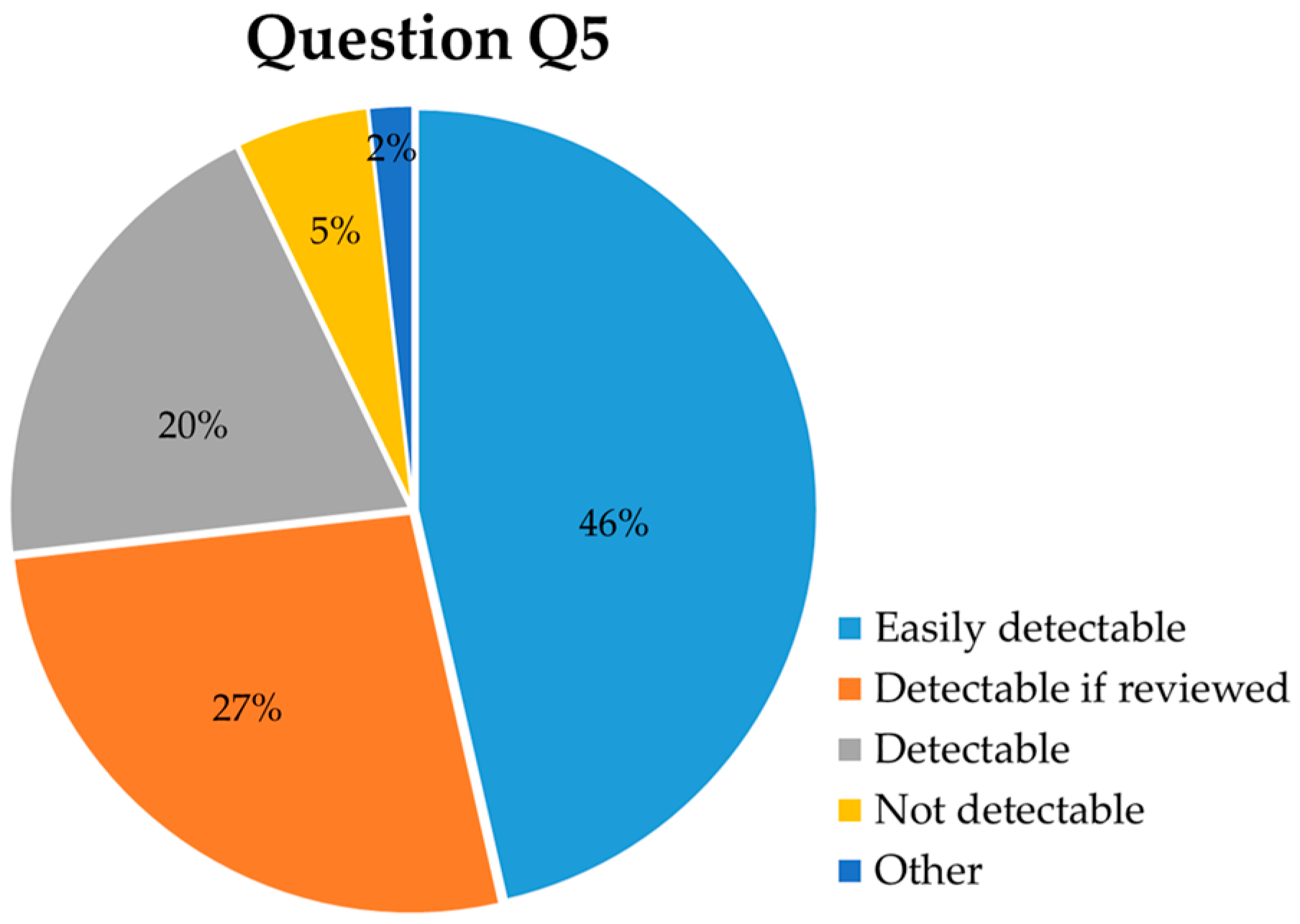

4.2. RQ2: What Do Students Believe About AI Text Detection?

- Q5: How do you perceive the detection of AI-based academic dishonesty in your writing?

Q5: Main Findings

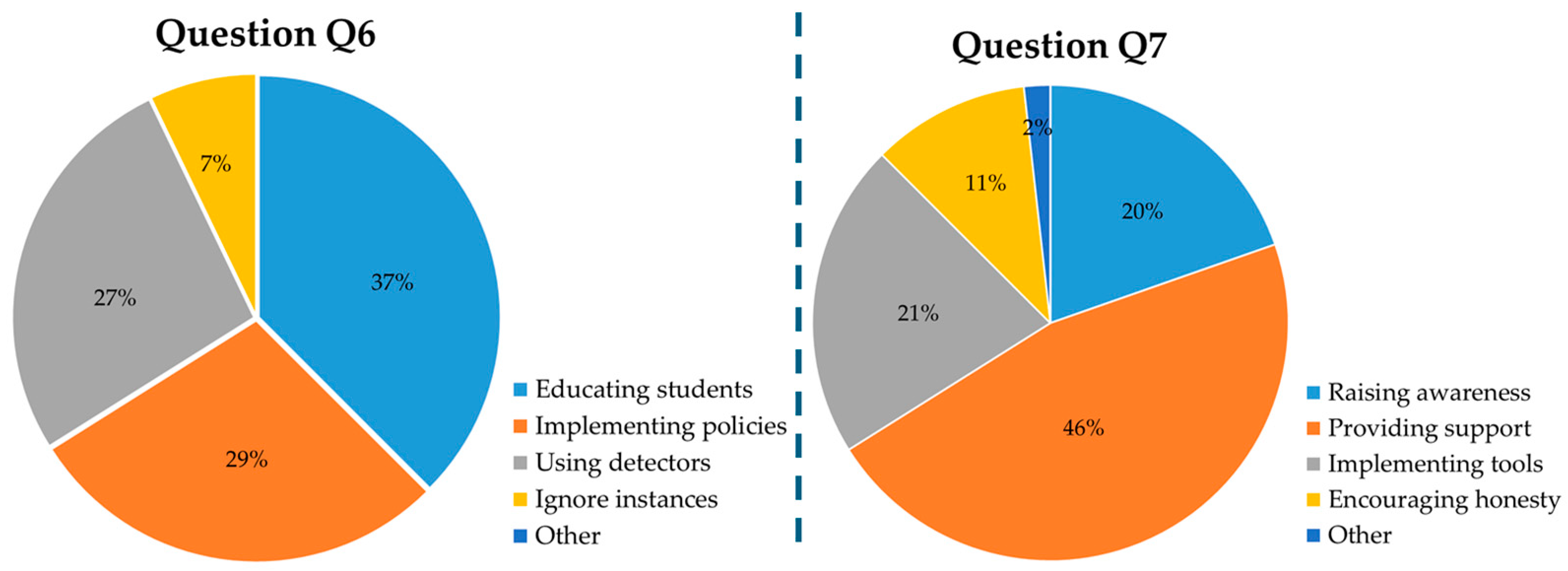

4.3. RQ3: How Should Authorities Respond to AI-Based Academic Dishonesty?

- Q6: How do you believe teachers or institutions should respond to AI-based academic dishonesty in writing?

- Q7: What measures do you believe could effectively prevent AI-based academic dishonesty in writing?

4.3.1. Q6: Main Findings

Unauthorized assistance:In a language class, evaluation is based on your ability to show that you are working towards mastery of the language, including showing skill with grammar, sentence structure, punctuation, and word choice that is appropriate to your level. You are not expected to produce perfect writing that is completely error-free and sounds like a native speaker wrote it. Rather, you should show that you have mastered the grammatical structures and vocabulary that have been covered in this course and in previous courses in the program. Because the teacher must have an accurate picture of your language skills at the time of evaluation, it is considered academically dishonest to use unauthorized assistance to complete your assignments. Unauthorized assistance may include, but is not limited to:

- ○

- ○

- ○

4.3.2. Q7: Main Findings

4.4. RQ4: Reasons for Typical and Acceptable Use of ChatGPT

- Q8: How do you perceive the use of AI tools like ChatGPT as a support for your writing tasks?

- Q9: In your opinion, is it correct to use AI tools like ChatGPT in your writing?

4.4.1. Q8: Main Findings

4.4.2. Q9: Main Findings

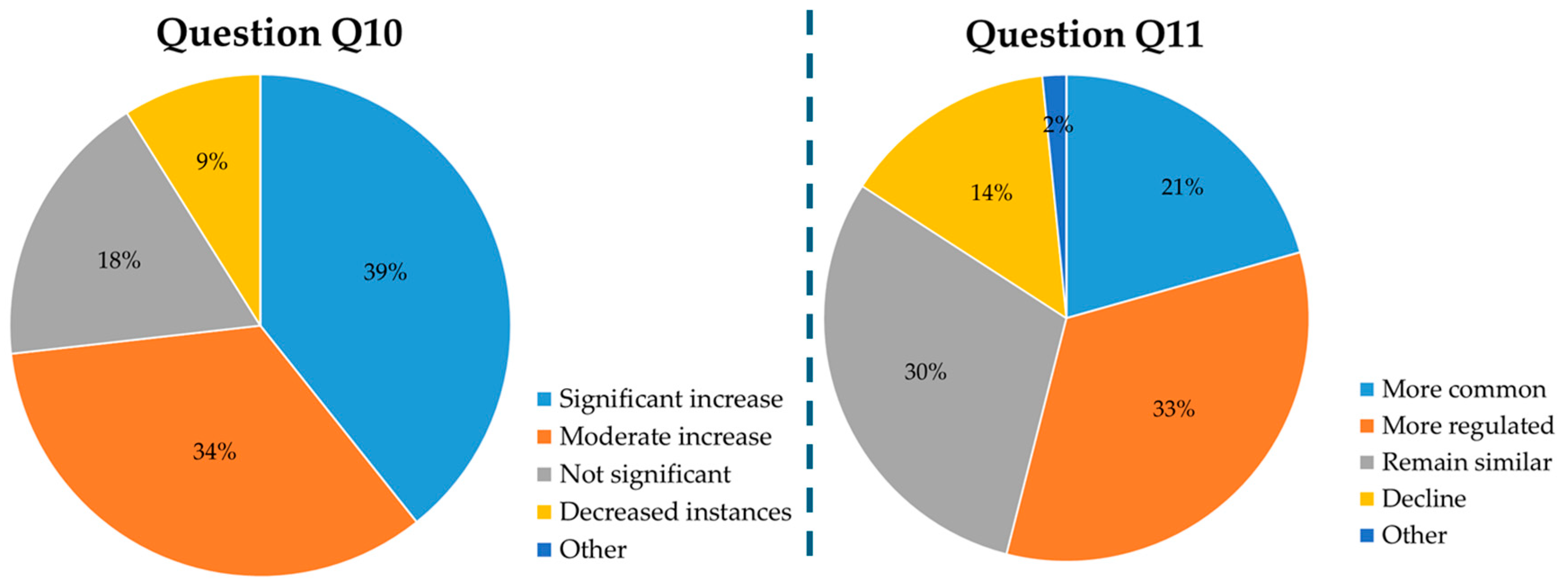

4.5. RQ5: Generative AI Effects on Academic Integrity and Writing Now and in the Future

- Q10: In your opinion, how has the arrival of AI technologies like ChatGPT impacted academic integrity in your writing production?

- Q11: How do you predict the use of AI tools like ChatGPT for writing will change in the near future?

4.5.1. Q10: Main Findings

4.5.2. Q11: Main Findings

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Questions

- Q1.

- How do you define academic dishonesty involving AI technologies like ChatGPT in the context of your writing production?

- (a)

- Copying and using exact texts without proper citations (copying texts)

- (b)

- Submitting AI-generated essays as my own work (submitting AI essays)

- (c)

- Using a translator to put Spanish version in English (translating)

- (d)

- All of the above

- (e)

- Other:______________________

- Q2.

- What specific examples can you provide for using AI technologies dishonestly in your writing?

- (a)

- Using AI to write entire essays or assignments (using AI)

- (b)

- Copying AI-generated text without paraphrasing (copying AI)

- (c)

- Using AI to improve my work without acknowledging the help (no acknowledgement)

- (d)

- All the above

- (e)

- Other:______________________

- Q3.

- What are the main reasons someone might use AI technologies dishonestly in your writing production?

- (a)

- Pressure to achieve high academic results (academic pressure)

- (b)

- Lack of confidence in my writing skills (confidence issues)

- (c)

- Belief that AI use is not easily detectable (AI detection)

- (d)

- Over-reliance on technology for convenience (over-reliance)

- (e)

- Other:______________________

- Q4.

- What do you believe are the consequences of using AI dishonestly in your writing?

- (a)

- Risk of being caught and facing academic penalties (academic penalties)

- (b)

- Hindering the development of my own writing skills (hindering development)

- (c)

- Creating a false sense of achievement (pseudo success)

- (d)

- All the above

- (e)

- Other:______________________

- Q5.

- How do you perceive the detection of AI-based academic dishonesty in your writing?

- (a)

- Easily detectable with current technology (easily detectable)

- (b)

- Difficult to detect unless closely reviewed (detectable if reviewed)

- (c)

- Only detectable if the work is inconsistent with my previous submissions (detectable)

- (d)

- Not detectable at all (not detectable)

- (e)

- Other:______________________

- Q6.

- How do you believe teachers or institutions should respond to AI-based academic dishonesty in writing?

- (a)

- Educating students on academic integrity and AI use (educating students)

- (b)

- Implementing stricter penalties for dishonesty (implementing policies)

- (c)

- Using AI-based plagiarism detectors (using detectors)

- (d)

- Ignoring or overlooking minor instances (ignore instances)

- (e)

- Other:______________________

- Q7.

- What measures do you believe could effectively prevent AI-based academic dishonesty in writing?

- (a)

- Raising awareness about the importance of original work (raising awareness)

- (b)

- Providing better support and resources for writing skills (providing support)

- (c)

- Implementing strict monitoring and detection tools (implementing tools)

- (d)

- Encouraging a culture of academic honesty (encouraging honesty)

- (e)

- Other:______________________

- Q8.

- How do you perceive the use of AI tools like ChatGPT as a support for your writing tasks?

- (a)

- A valuable learning tool (valuable tool)

- (b)

- Save time on writing assignments (saves time)

- (c)

- Source of ideas and inspiration (brainstorming)

- (d)

- Bypass difficult part of writing (writer’s block)

- (e)

- Risk of becoming dependent on AI (dependence risk)

- (f)

- Other:______________________

- Q9.

- In your opinion, is it correct to use AI tools like ChatGPT in your writing?

- (a)

- Yes, it is completely acceptable (yes, completely acceptable)

- (b)

- Yes, but only if properly cited (yes, if cited)

- (c)

- It depends on the context or extent of use (depends)

- (d)

- No, it is not acceptable (no, not acceptable)

- (e)

- Other:______________________

- Q10.

- In your opinion, how has the arrival of AI technologies like ChatGPT impacted academic integrity in your writing production?

- (a)

- Significantly increased instances of academic dishonesty (significant increase)

- (b)

- Moderately increased instances of academic dishonesty (moderate increase)

- (c)

- Not significant impact (not significant)

- (d)

- Decreased instances of academic dishonesty due to better detection tools (decreased instances)

- (e)

- Other:______________________

- Q11.

- How do you predict the use of AI tools like ChatGPT for writing will change in the near future?”

- (a)

- It will become more common and widely accepted (more common)

- (b)

- It will be more strictly regulated by educational institutions (more regulated)

- (c)

- It will remain similar to current usage patterns (remain similar)

- (d)

- It will decline due to ethical concerns and detection technologies (decline)

- (e)

- Other:______________________

References

- Abbas, M., Jam, F. A., & Khan, T. I. (2024). Is it harmful or helpful? Examining the causes and consequences of generative AI usage among university students. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Enriquez, B. G., Arbulú Ballesteros, M. A., Huamaní Jordan, O., López Roca, C., & Saavedra Tirado, K. (2024). Analysis of college students’ attitudes toward the use of ChatGPT in their academic activities: Effect of intent to use, verification of information and responsible use. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAfnan, M. A., Dishari, S., Jovic, M., & Lomidze, K. (2023). ChatGPT as an educational tool: Opportunities, challenges, and recommendations for communication, business writing, and composition courses. Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Technology, 3(2), 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAfnan, M. A., & MohdZuki, S. F. (2023). Do artificial intelligence chatbots have a writing style? An investigation into the stylistic features of ChatGPT-4. Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Technology, 3(3), 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayati, H. (2024). Investigating undergraduate students’ perceptions and awareness of using ChatGPT as a regular assistance tool: A user acceptance perspective study. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, K., Savvidou, C., & Alexander, C. (2023). Who wrote this essay? Detecting AI-generated writing in second language education in higher education. Teaching English with Technology, 23(2), 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghannam, M. S. M. (2024). Artificial intelligence as a provider of feedback on EFL student compositions. World Journal of English Language, 15(2), 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusharraf, A., & Bailey, D. (2023). Machine translation in language acquisition: A study on EFL students’ perceptions and practices in Saudi Arabia and South Korea. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 39(6), 1988–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, N., & Joy, M. (2021, September 1–3). English-Arabic cross-language plagiarism detection. International Conference on Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing (pp. 44–52), Online. [Google Scholar]

- Amineh, R. J., & Asl, H. D. (2015). Review of constructivism and social constructivism. Journal of Social Sciences, Literature and Languages, 1(1), 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Anani, G. E., Nyamekye, E., & Bafour-Koduah, D. (2025). Using artificial intelligence for academic writing in higher education: The perspectives of university students in Ghana. Discover Education, 4(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeles, C. N., Samson, B. D., Mama, B. R. Z. I., Luriaga, R. L., Delizo, J. P. D., & Ching, M. R. D. (2024, May 28–30). Students’perception of the use of AI detector system by faculty members in determining the originality of submitted academic requirements. 2024 8th International Conference on E-Commerce, E-Business, and E-Government (pp. 56–61), Ajman, United Arab Emirates. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anson, C. M. (2022). AI-based text generation and the social construction of “fraudulent authorship”: A revisitation. Composition Studies, 51(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Applefield, J. M., Huber, R., & Moallem, M. (2001). Constructivism in theory and practice: Toward a better understanding. High School Journal, 84(2), 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ateeq, A., Alzoraiki, M., Milhem, M., & Ateeq, R. A. (2024). Artificial intelligence in education: Implications for academic integrity and the shift toward holistic assessment. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1470979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoulay, R., Hirst, T., & Reches, S. (2023). Let’s do it ourselves: Ensuring academic integrity in the age of ChatGPT and beyond. echRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidoo-Anu, D., & Owusu Ansah, L. (2023). Education in the era of generative artificial intelligence (AI): Understanding the potential benefits of ChatGPT in promoting teaching and learning. SSRN Electronic Journal, 7(1), 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruchson-Arbib, S. (2004). A study of students’ perception. The International Review of Information Ethics, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belle, N., & Cantarelli, P. (2017). What causes unethical behavior? A meta-analysis to set an agenda for public administration research. Public Administration Review, 77(3), 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikanga Ada, M. (2024). It helps with crap lecturers and their low effort: Investigating computer science students’ perceptions of using ChatGPT for learning. Education Sciences, 14(10), 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitzenbauer, P. (2023). ChatGPT in physics education: A pilot study on easy-to-implement activities. Contemporary Educational Technology, 15(3), ep430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsu, E. M., & Baffour-Koduah, D. (2023). From the consumers’ side: Determining students’ perception and intention to use ChatGPT in ghanaian higher education. Journal of Education, Society & Multiculturalism, 4(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brainard, J. (2023). Journals take up arms against AI-written text. Science, 379(6634), 740–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, Z. B., Duman, H., Buluş, B., & Erişen, Y. (2023). How did ChatGPT transform us in terms of transformative learning? Journal of Social and Educational Research, 2(2), 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, J. (2013). A handbook for deterring plagiarism in higher education (2nd ed.). Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, H., Hussey, J., & Forehand, J. W. (2019). Plagiarism in nursing education and the ethical implications in practice. Heliyon, 5(3), e01350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, L., & Selwyn, N. (2018). More than tools? Making sense of the ongoing digitizations of higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. K. Y. (2023). Is AI changing the rules of academic misconduct? An in-depth look at students’ perceptions of “AI-giarism”. arXiv, arXiv:2306.03358. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2306.03358 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Chan, C. K. Y. (2025). Students’ perceptions of ‘AI-giarism’: Investigating changes in understandings of academic misconduct. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 8087–8108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, J., & Dethlefs, N. (2023). This new conversational AI model can be your friend, philosopher, and guide … and even your worst enemy. Patterns, 4(1), 100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-J. (2023). ChatGPT and other artificial intelligence applications speed up scientific writing. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association, 86(4), 351–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrez-Ojeda, I., Gallardo-Bastidas, J. C., Robles-Velasco, K., Osorio, M. F., Velez Leon, E. M., Leon Velastegui, M., Pauletto, P., Aguilar-Díaz, F. C., Squassi, A., González Eras, S. P., Cordero Carrasco, E., Chavez Gonzalez, K. L., Calderon, J. C., Bousquet, J., Bedbrook, A., & Faytong-Haro, M. (2024). Understanding health care students’ perceptions, beliefs, and attitudes toward AI-powered language models: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Medical Education, 10, e51757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, F., Zhu, D., & Yu, W. (2022). A systematic review of academic dishonesty in online learning environments. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(4), 907–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, F., & Tan, K. (2023). Abrupt academic dishonesty: Pressure, opportunity, and deterrence. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(2), 100815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, M., Carey, M., Robertson, A., & Grainger, P. (2015). Putting transformative learning theory into practice. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 55(1), 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, E., August, T., Serrano, S., Haduong, N., Gururangan, S., & Smith, N. A. (2021, August 1–6). All that’s ‘Human’ is not gold: Evaluating human evaluation of generated text. 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Vol. 1: Long Papers, pp. 7282–7296), Bangkok, Thailand. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, O., Chan, W. Y. D., Bukuru, S., Logan, J., & Wong, R. (2023). Assessing knowledge of and attitudes towards plagiarism and ability to recognize plagiaristic writing among university students in Rwanda. Higher Education, 85(2), 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Columbia University. (2024). Teachers college Institutional Review Board (IRB). Available online: https://www.tc.columbia.edu/institutional-review-board/ (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Cotton, D. R. E., Cotton, P. A., & Shipway, J. R. (2024). Chatting and cheating: Ensuring academic integrity in the Era of ChatGPT. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 61(2), 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S. R., & Madhusudan, J. V. (2024). Perceptions of higher education students towards ChatGPT usage. International Journal of Technology in Education, 7(1), 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, I. G. J., & Hanoch, Y. M. (2024). The role of perceived risk on dishonest decision making during a pandemic. Risk Analysis, 44(12), 2762–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delello, J. A., Sung, W., Mokhtari, K., Hebert, J., Bronson, A., & De Giuseppe, T. (2025). AI in the classroom: Insights from educators on usage, challenges, and mental health. Education Sciences, 15(2), 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dergaa, I., Chamari, K., Zmijewski, P., & Ben Saad, H. (2023). From human writing to artificial intelligence generated text: Examining the prospects and potential threats of ChatGPT in academic writing. Biology of Sport, 40(2), 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinneen, C. (2021). Students’ use of digital translation and paraphrasing tools in written assignments on direct entry english Programs. English Australia Journal, 37(1), 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- DiVall, M. V., & Schlesselman, L. S. (2016). Academic dishonesty: Whose fault is it anyway? American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 80(3), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducar, C., & Schocket, D. H. (2018). Machine translation and the L2 classroom: Pedagogical solutions for making peace with Google translate. Foreign Language Annals, 51(4), 779–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egloff, J. (2024). The college essay is not dead. Proceedings of the H-Net Teaching Conference, 2, 72–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhodr, M., Gide, E., Wu, R., & Darwish, O. (2023). ICT students’ perceptions towards ChatGPT: An experimental reflective lab analysis. STEM Education, 3(2), 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkhtur, A., & Yamamoto, B. A. (2017). Transformative learning theory and its application in higher education settings: A review paper. Bulletin of the Graduate School of Human Sciences, Osaka University, 43, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajt, B., & Schiller, E. (2025). ChatGPT in academia: University students’ attitudes towards the use of ChatGPT and plagiarism. Journal of Academic Ethics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhi, F., Jeljeli, R., Aburezeq, I., Dweikat, F. F., Al-shami, S. A., & Slamene, R. (2023). Analyzing the students’ views, concerns, and perceived ethics about chat GPT usage. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence, 5, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrokhnia, M., Banihashem, S. K., Noroozi, O., & Wals, A. (2024). A SWOT analysis of ChatGPT: Implications for educational practice and research. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 61(3), 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, A. (2023). Can GPT-4 fool turnItIn? Testing the limits of AI detection with prompt engineering. In IPHS 300: Artificial intelligence for the humanities: Text, image, and sound (p. p. 39). Digital Kenyon. Available online: https://digital.kenyon.edu/dh_iphs_ai/39 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum International Publishing Group Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Gamliel, E., & Peer, E. (2013). Explicit risk of getting caught does not affect unethical behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(6), 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C. A., Howard, F. M., Markov, N. S., Dyer, E. C., Ramesh, S., Luo, Y., & Pearson, A. T. (2023). Comparing scientific abstracts generated by ChatGPT to real abstracts with detectors and blinded human reviewers. Npj Digital Medicine, 6(1), 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A. S., George, A. S. H., & Martin, A. S. G. (2023). A review of ChatGPT AI’s impact on several business sectors. Partners Universal International Innovation Journal, 1(1), 9–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlich, M. (2025). AI tools in society: Impacts on cognitive offloading and the future of critical thinking. Societies, 15(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghounane, N., Al-Zubaidi, K., & Rahmani, A. (2024). Exploring algerian EFL master’s students’ attitudes toward AI-giarism. Indonesian Journal of Socual Science Research, 5(2), 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, D., Kovanovic, V., Ifenthaler, D., Dexter, S., & Feng, S. (2023). Learning theories for artificial intelligence promoting learning processes. British Journal of Educational Technology, 54(5), 1125–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorichanaz, T. (2023). Accused: How students respond to allegations of using ChatGPT on assessments. Learning: Research and Practice, 9(2), 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M. U., Dharmadasa, I., Sworna, Z. T., Rajapakse, R. N., & Ahmad, H. (2022). “I think this is the most disruptive technology”: Exploring sentiments of ChatGPT early adopters using Twitter data. arXiv, arXiv:2212.05856. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2212.05856 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Heidt, A. (2025). ChatGPT for students: Learners find creative new uses for chatbots. Nature, 639(8053), 265–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, E. S. (2023). Hey ChatGPT! Write me an article about your effects on academic writing. Anthropology Now, 15(1), 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heriyati, D., & Ekasari, W. F. (2020). A study on academic dishonesty and moral reasoning. International Journal of Education, 12(2), 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, R. M. (1995). Plagiarisms, authorships, and the academic death penalty. College English, 57(7), 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M., Lambin, X., & Villard, E. (2022). The role of prior warnings when cheating is easy and punishment is credible. Information Economics and Policy, 58, 100959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K. (2023). Using AI-based detectors to control AI-assisted plagiarism in ESL writing: “The Terminator Versus the Machines”. Language Testing in Asia, 13(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A. (2017). ICT pedagogy in higher education: A constructivist approach. Journal of Training and Development, 3, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomaa, N., Attamimi, R., & Al Mahri, M. (2024). The use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in teaching english vocabulary in Oman: Perspectives, teaching practices, and challenges. World Journal of English Language, 15(3), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M., & Er, E. (2023). Will ChatGPT get you caught? Rethinking of plagiarism detection. EdArXiv Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibler, W. L. (1993). Academic dishonesty: A student development dilema. NASPA Journal, 30(4), 252–267. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ468340 (accessed on 15 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, A. (2008). The evolution of John Mezirow’s transformative learning theory. Journal of Transformative Education, 6(2), 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohnke, L., Moorhouse, B. L., & Zou, D. (2023). ChatGPT for language teaching and learning. RELC Journal, 54(2), 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koos, S., & Wachsmann, S. (2023). Navigating the impact of ChatGPT/GPT4 on legal academic examinations: Challenges, opportunities and recommendations. Media Iuris, 6(2), 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladha, N., Yadav, K., & Rathore, P. (2023). AI-generated content detectors: Boon or bane for scientific writing. Indian Journal of Science And Technology, 16(39), 3435–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E. G., Hogan, N. L., & Barton, S. M. (2003). Collegiate academic dishonesty revisited: What have they done, how often have they done it, who does it, and why did they do it? Electronic Journal of Sociology, 7, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Leong, W. Y., & Bing, Z. J. (2025). AI on academic integrity and plagiarism detection. ASM Science Journal, 20(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhutfi, I., Hardiana, R. D., & Mardiani, R. (2021). Fraud pentagon model: Predicting student’s cheating academic behavior. Jurnal ASET (Akuntansi Riset), 13(2), 234–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B., Bonk, C. J., & Kou, X. (2023). Exploring the multilingual applications of ChatGPT. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching, 13(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W., Yuksekgonul, M., Mao, Y., Wu, E., & Zou, J. (2023). GPT detectors are biased against non-native English writers. Patterns, 4(7), 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, F. V., & Toh, W. (2024). Apps for English language learning: A systematic review. Teaching English With Technology, 2024(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., & Wang, Y. (2024). The effects of using AI tools on critical thinking in English literature classes among EFL learners: An intervention study. European Journal of Education, 59(4), e12804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C. K. (2023). What is the impact of ChatGPT on education? A rapid review of the literature. Education Sciences, 13(4), 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C. K., Yu, P. L. H., Xu, S., Ng, D. T. K., & Jong, M. S. (2024). Exploring the application of ChatGPT in ESL/EFL education and related research issues: A systematic review of empirical studies. Smart Learning Environments, 11(1), 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, B. (2023, May). A short history of ChatGPT: How we got to where we are today. Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/bernardmarr/2023/05/19/a-short-history-of-chatgpt-how-we-got-to-where-we-are-today/#open-web-0 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- McGuire, A., Qureshi, W., & Saad, M. (2024). A constructivist model for leveraging GenAI tools for individualized, peer-simulated feedback on student writing. International Journal of Technology in Education, 7(2), 326–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, V. (2023). ChatGPT: An AI NLP model. Available online: https://www.ltimindtree.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/ChatGPT-An-AI-NLP-Model-POV.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Mendoza, J. J. N. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ reflection logs: Pieces of evidence of transformative teaching and emancipation. International Journal of Higher Education, 9(6), 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. (2003). Transformative learning as discourse. Journal of Transformative Education, 1(1), 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijwil, M. M., Hiran, K. K., Doshi, R., Dadhich, M., Al-Mistarehi, A.-H., & Bala, I. (2023). ChatGPT and the future of academic integrity in the artificial intelligence era: A new frontier. Al-Salam Journal for Engineering and Technology, 2(2), 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S., & Kinyo, L. (2020). Constructivist theory as a foundation for the utilization of digital technology in the lifelong learning process. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 21(4), 90–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A., Santamaría, P., & Javens, J. (2024). Students’ perceptions of generative AI use in academic writing. In Pixel (Ed.), 17th international conference “innovation in language learning” (pp. 237–245). Filodiritto—inFOROmatica S.r.l. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, T. T. A. (2023). The perception by university students of the use of ChatGPT in education. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (IJET), 18(17), 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C. (2017). In Other (People’s) Words: Plagiarism by university students—Literature and lessons. In R. Barrow, & P. Keeney (Eds.), Academic ethics (1st ed., pp. 525–542). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pavela, G. (1997). Applying the power of association on campus: A model code of academic integrity. Journal of College and University Law, 24(1), 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Pecorari, D. (2013). Teaching to avoid plagiarism: How to promote good source use (1st ed.). Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins, M. (2023). Academic integrity considerations of AI large language models in the post-pandemic era: ChatGPT and beyond. Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice, 20(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudasaini, S., Miralles-Pechuán, L., Lillis, D., & Salvador, M. L. (2024). Survey on plagiarism detection in large language models: The Impact of ChatGPT and gemini on academic integrity. arXiv, arXiv:2407.13105. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2407.13105 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Puspitosari, I. (2022). Fraud triangle theory on accounting students online academic cheating. Accounting and Finance Studies, 2(4), 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadir, J. (2022). Engineering education in the Era of ChatGPT: Promise and pitfalls of generative AI for education. TechRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. S., Sabbir, M. M., Zhang, D. J., Moral, I. H., & Hossain, G. M. S. (2023). Examining students’ intention to use ChatGPT: Does trust matter? Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 39, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, T., Nair, S., Kalendra, D., Robin, M., de Oliveira Santini, F., Ladeira, W. J., Sun, M., Day, I., Rather, R. A., & Heathcote, L. (2023). The role of ChatGPT in higher education: Benefits, challenges, and future research directions. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 6(1), 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratna, A. A. P., Purnamasari, P. D., Adhi, B. A., Ekadiyanto, F. A., Salman, M., Mardiyah, M., & Winata, D. J. (2017). Cross-language plagiarism detection system using latent semantic analysis and learning vector quantization. Algorithms, 10(2), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricaurte, M., Ordóñez, P. E., Navas-Cárdenas, C., Meneses, M. A., Tafur, J. P., & Viloria, A. (2022). Industrial processes online teaching: A good practice for undergraduate engineering students in times of COVID-19. Sustainability, 14(8), 4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricaurte, M., & Viloria, A. (2020). Project-based learning as a strategy for multi-level training applied to undergraduate engineering students. Education for Chemical Engineers, 33, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M., Silva, R., Borges, A. P., Franco, M., & Oliveira, C. (2025). Artificial intelligence: Threat or asset to academic integrity? A bibliometric analysis. Kybernetes, 54(5), 2939–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Acosta, D., Rodríguez Torres, M., Baquedano Montoya, M., López Zabala, L., & Pérez Gamboa, A. (2024). ChatGPT and its use to improve academic writing in postgraduate students. PRA, 24(36), 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, J., Tan, S., & Tan, S. (2023). ChatGPT: Bullshit spewer or the end of traditional assessments in higher education? Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 6(1), 342–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvagno, M., Taccone, F. S., & Gerli, A. G. (2023). Correction to: Can artificial intelligence help for scientific writing? Critical Care, 27(1), 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N. (2008). ‘Not necessarily a bad thing …’: A study of online plagiarism amongst undergraduate students. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(5), 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadiev, R., Chen, X., & Altinay, F. (2024). A review of research on computer-aided translation technologies and their applications to assist learning and instruction. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 40(6), 3290–3323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sila, C. A., William, C., Yunus, M. M., & M. Rafiq, K. R. (2023). Exploring students’ perception of using ChatGPT in higher education. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 13(12), 4044–4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H., Tayarani-Najaran, M.-H., & Yaqoob, M. (2023). Exploring computer science students’ perception of ChatGPT in higher education: A descriptive and correlation study. Education Sciences, 13(9), 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokel-Walker, C. (2022). AI bot ChatGPT writes smart essays—Should professors worry? Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M., Kelly, A., & McLaughlan, P. (2023). ChatGPT in higher education: Considerations for academic integrity and student learning. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 6(1), 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suneetha, Y. (2014). Constructive classroom: A cognitive instructional strategy in ELT. I-Manager’s Journal on English Language Teaching, 4(1), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, T., & Zhou, M. (2017). The influence of teachers’ conceptions of teaching and learning on their technology acceptance. Interactive Learning Environments, 25(4), 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp, H. H. (2023). ChatGPT is fun, but not an author. Science, 379(6630), 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tram, N. H. M., Nguyen, T. T., & Tran, C. D. (2024). ChatGPT as a tool for self-learning English among EFL learners: A multi-methods study. System, 127, 103528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Waterloo. (2024). Research with human participants. Available online: https://uwaterloo.ca/research/office-research-ethics/research-human-participants (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Urlaub, P., & Dessein, E. (2022). From disrupted classrooms to human-machine collaboration? The pocket calculator, Google Translate, and the future of language education. L2 Journal, 14(1), 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, L. (2023). ChatGPT and academic integrity concerns: Detecting artificial intelligence-generated content. Language Education & Technology, 3(1), 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Valova, I., Mladenova, T., & Kanev, G. (2024). Students’ perception of ChatGPT usage in education. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 15(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lieshout, C., & Cardoso, W. (2022). Google Translate as a tool for self-directed language learning. Language Learning & Technology, 26(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Von, G. E. (1995). A Constructivist Approach to Teaching. In Constructivism in education (pp. 3–15). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., & Kim, E. (2023). Exploring changes in epistemological beliefs and beliefs about teaching and learning: A mix-method study among Chinese teachers in transnational higher education institutions. Sustainability, 15(16), 12501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger-Trayner, E., Wenger-Trayner, B., Reid, P., & Bruderlein, C. (2023). Communities of practice within and across organization: A guidebook (2nd ed.). Social Learning Lab. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, F., Zhu, S., & Xin, W. (2025). Exploring the landscape of generative AI (ChatGPT)-powered writing instruction in English as a foreign language education: A scoping review. ECNU Review of Education, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y., & Zhi, Y. (2023). An exploratory study of EFL learners’ use of ChatGPT for language learning tasks: Experience and perceptions. Languages, 8(3), 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Cox, A., & Cai, L. (2024). ChatGPT and the digitisation of writing. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubarev, D., Tikhomirov, I., & Sochenkov, I. (2022). Cross-lingual plagiarism detection method (pp. 207–222). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nelson, A.S.; Santamaría, P.V.; Javens, J.S.; Ricaurte, M. Students’ Perceptions of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) Use in Academic Writing in English as a Foreign Language. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050611

Nelson AS, Santamaría PV, Javens JS, Ricaurte M. Students’ Perceptions of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) Use in Academic Writing in English as a Foreign Language. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):611. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050611

Chicago/Turabian StyleNelson, Andrew S., Paola V. Santamaría, Josephine S. Javens, and Marvin Ricaurte. 2025. "Students’ Perceptions of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) Use in Academic Writing in English as a Foreign Language" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050611

APA StyleNelson, A. S., Santamaría, P. V., Javens, J. S., & Ricaurte, M. (2025). Students’ Perceptions of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) Use in Academic Writing in English as a Foreign Language. Education Sciences, 15(5), 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050611