A Systematic Scoping Review on the Transition of Under-3-Year-Old Children from Home to Early Childhood Education and Care

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Questions

- How many peer-reviewed research articles have been published on the transition of under-3-year-olds from home to ECEC, and what are the characteristics of these studies in terms of their year of publication, country, continent, and purpose?

- Which methodologies have been used in peer-reviewed research articles that have been published on the transition of under-3-year-olds from home to ECEC?

- Which concepts have been examined in peer-reviewed research articles that have been published on the transition of under-3-year-olds from home to ECEC?

- Which findings and implications do peer-reviewed research articles present on the transition of under-3-year-olds from home to ECEC?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Inclusion Criteria

3.2. Literature Search

3.3. Screening Process

3.4. Data Extraction

4. Results

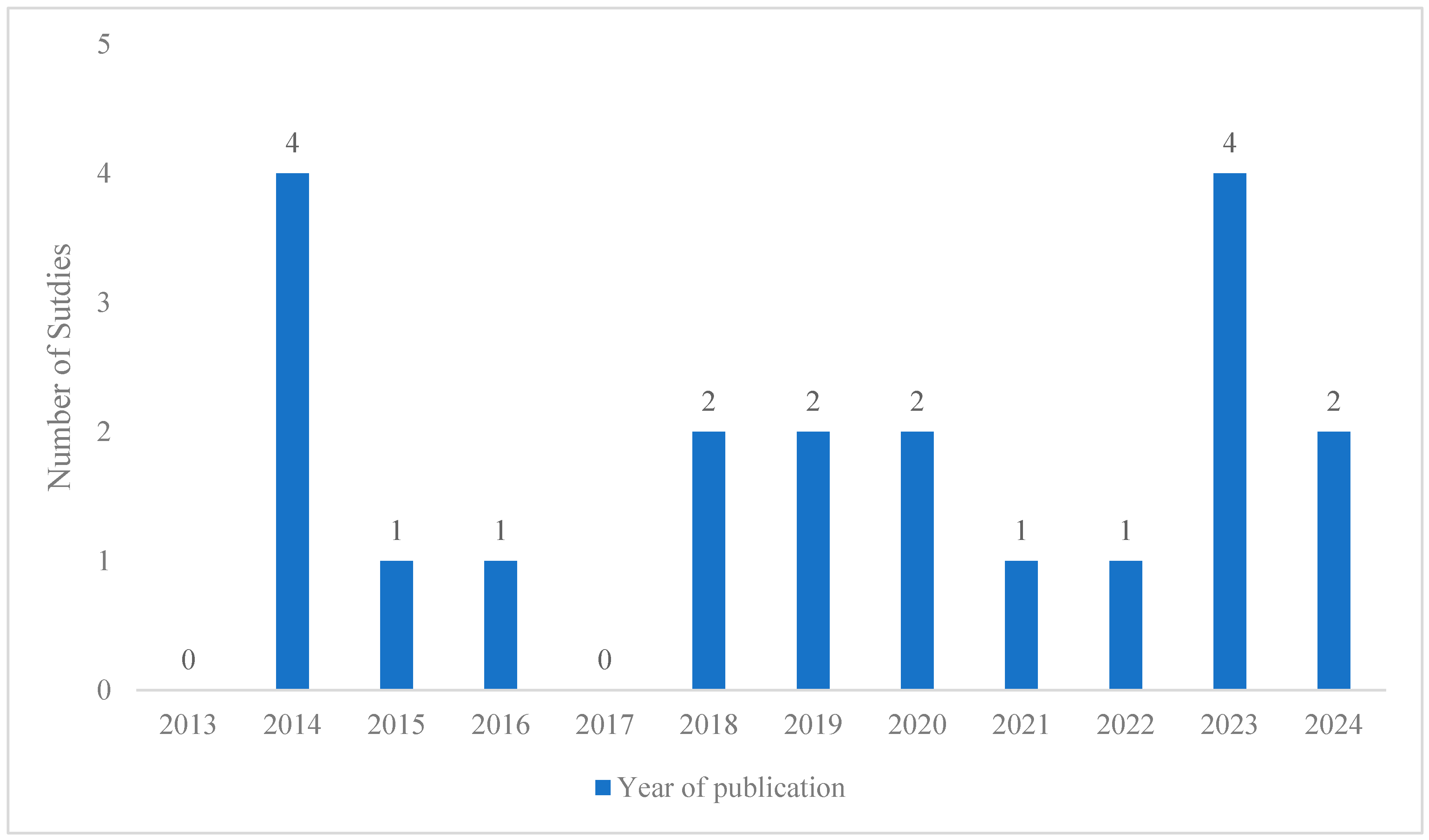

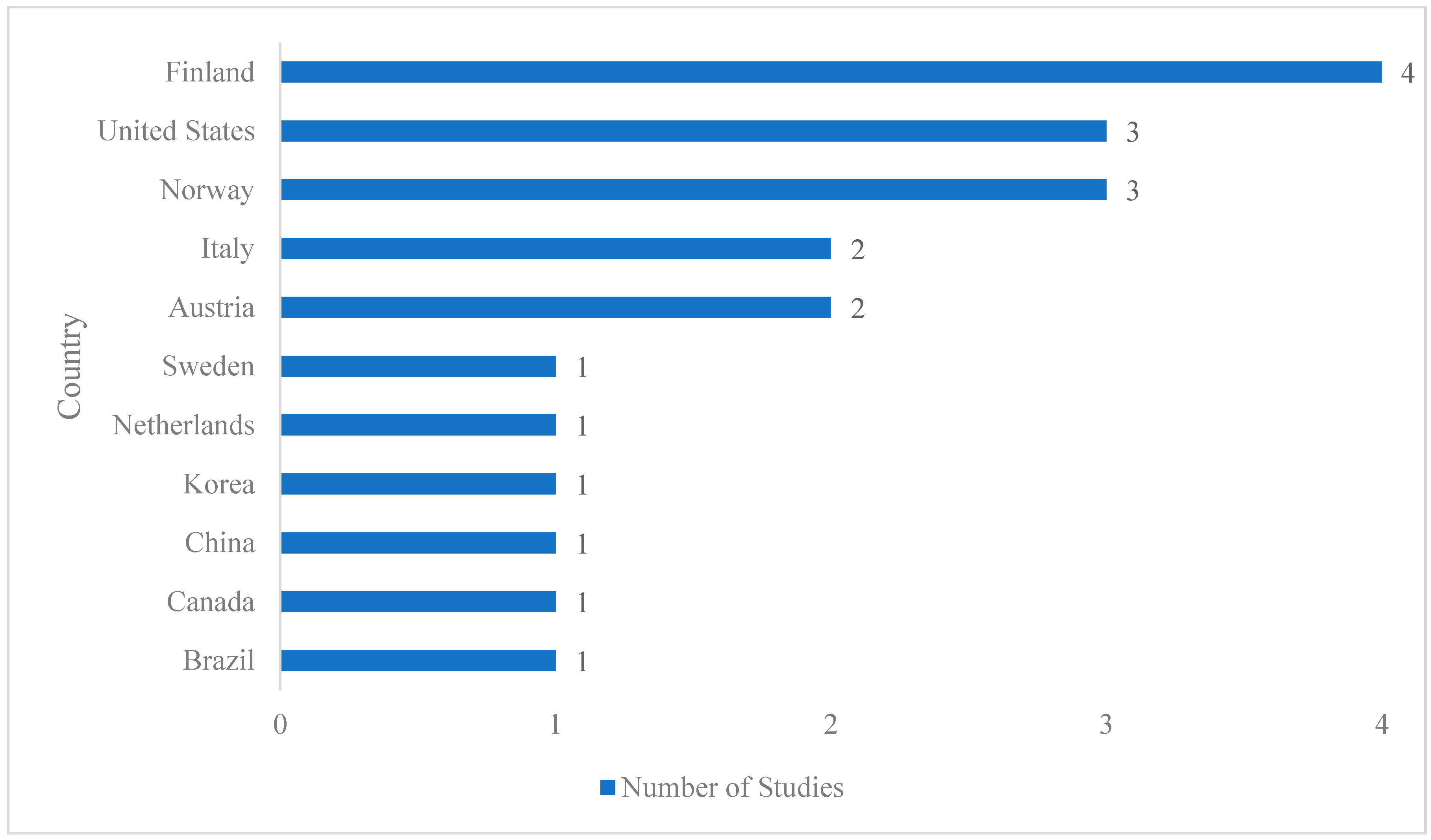

4.1. Characteristics of the Studies

4.2. Methodological Approaches

4.3. Sample Characteristics

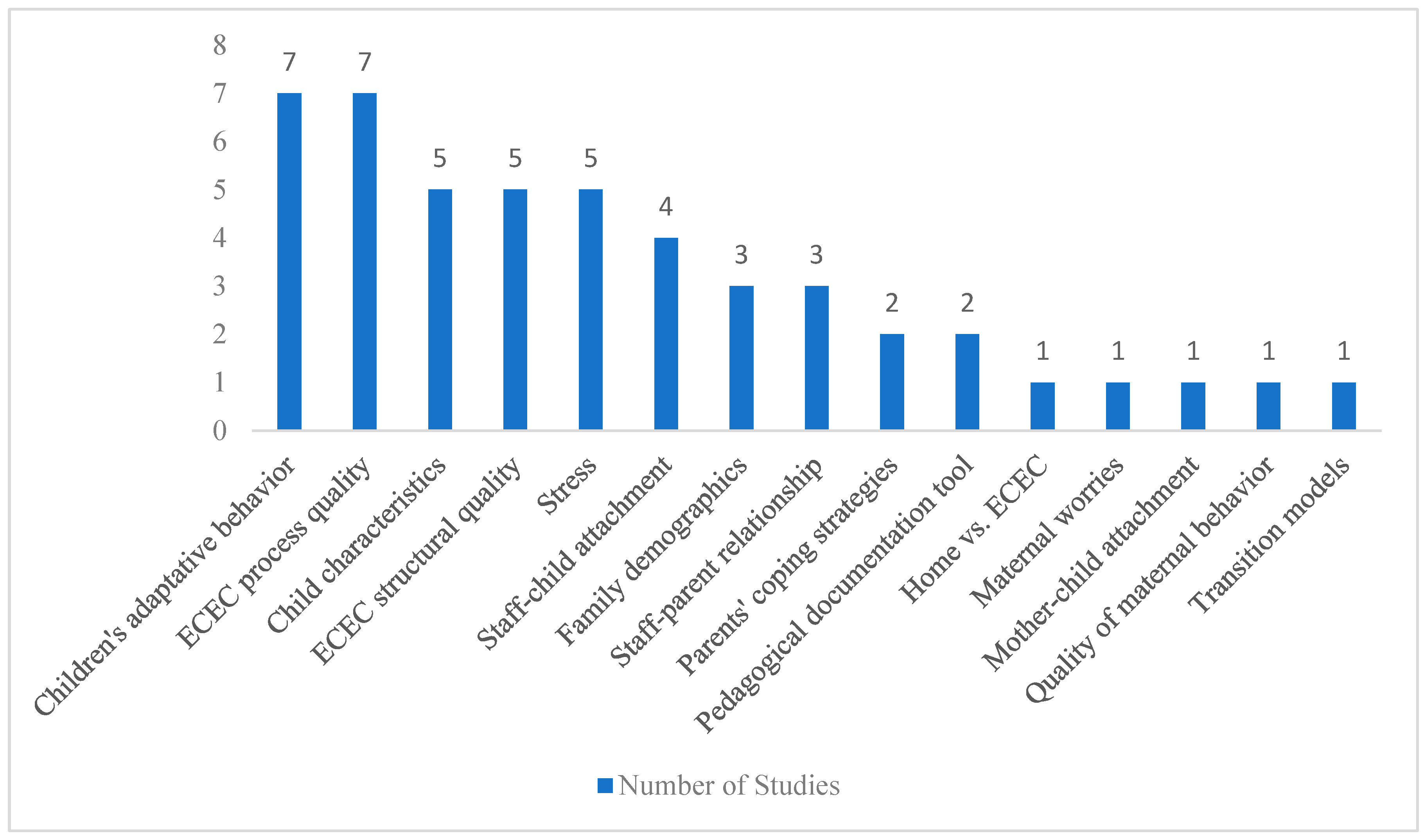

4.4. Concepts

4.5. Findings and Implications

5. Discussion

5.1. Characteristics of the Studies

5.2. Methodological Approaches

5.3. Sample Characteristics

5.4. Concepts

5.5. Findings and Implications

6. Limitations

7. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Full Search Strategies, Filters, and Limits per Database

| Database | Search String | Number of Results on 19 August 2024 |

|---|---|---|

| Academic Search Premier | “(toddler* OR 0–3 OR “children under 3 years old” OR “children under 3” OR “young* child*”) AND (ECEC* OR ECE* OR “ECEC center” OR “ECE center” OR “ECEC centre” OR “ECE centre” OR daycare OR “day care” OR “daycare center” OR “daycare centre” OR “day care center” OR “day care centre” OR childcare* OR “child care*” OR “childcare center*” OR “child care center*” OR “childcare centre*” OR “child care centre*” OR “centerbased care” OR “centrebased care” OR “centerbased childcare” OR “centrebased childcare” OR “centerbased child care” OR “centrebased child care” OR “center-based childcare” OR “centre-based childcare” OR “center-based child care” OR “centre-based child care” OR preschool* OR pre-school* OR kindergarten* OR “early childhood education” OR “early childhood education and care” OR crèche* OR creche* OR nurser* OR “day nurser*” OR “nursery school*” OR “infant school*” OR playschool* OR “play school*” OR “pre-primary school*”) AND (transition* OR “transition period” OR “transition phase” OR starting* OR “starting period” OR “starting phase”) Peer Reviewed; Published Date: 1 January 2013–31 December 2024 on 18 August 2024 09:01 AM” | N = 319 |

| Eric | “(toddler* OR 0–3 OR “children under 3 years old” OR “children under 3” OR “young* child*”) AND (ECEC* OR ECE* OR “ECEC center” OR “ECE center” OR “ECEC centre” OR “ECE centre” OR daycare OR “day care” OR “daycare center” OR “daycare centre” OR “day care center” OR “day care centre” OR childcare* OR “child care*” OR “childcare center*” OR “child care center*” OR “childcare centre*” OR “child care centre*” OR “centerbased care” OR “centrebased care” OR “centerbased childcare” OR “centrebased childcare” OR “centerbased child care” OR “centrebased child care” OR “center-based childcare” OR “centre-based childcare” OR “center-based child care” OR “centre-based child care” OR preschool* OR pre-school* OR kindergarten* OR “early childhood education” OR “early childhood education and care” OR crèche* OR creche* OR nurser* OR “day nurser*” OR “nursery school*” OR “infant school*” OR playschool* OR “play school*” OR “pre-primary school*”) AND (transition* OR “transition period” OR “transition phase” OR starting* OR “starting period” OR “starting phase”) Peer Reviewed; Date Published: 1 January 2013–31 December 2024 on 18 August 2024 08:06 AM” | N = 359 |

| Idunn—Danish | [[All: børn*] OR [All: småbørn] OR [All: vuggestuebørn] OR [All: “1–3 år”]] AND [[All: børnehave*] OR [All: vuggestue*] OR [All: dagpleje*]] AND [[All: overgang*] OR [All: modtakelse] OR [All: indkjøring]] AND [Publication Date: (1 January 2013 TO 31 December 2024)] | N = 10 |

| Idunn—Norwegian | [[All: småbarn] OR [All: “små barn”] OR [All: “1–3 åring*”] OR [All: “ettåring*”] OR [All: “ett-til-treåring*”] OR [All: “de yngste barna”] OR [All: “de minste barna”]] AND [[All: barnehage] OR [All: småbarnsavdeling] OR [All: småbarnsgruppe]] AND [[All: “foreldreaktiv tilvenning”] OR [All: “start i barnehagen”] OR [All: tilvenning] OR [All: innkjøring] OR [All: oppstart] OR [All: overgang] OR [All: “sammenheng mellom hjem og barnehage”]] AND [Publication Date: (1 January 2013 TO 31 December 2024)] | N = 36 |

| Idunn—Swedish | [[All: barn*] OR [All: “små barn*”] OR [All: “yngre barn*”]] AND [[All: inskolning*] OR [All: “aktivt föräldraskap”] OR [All: uppstart*]] AND [[All: førskolan] OR [All: dagis*]] AND [Publication Date: (1 January 2013 TO 31 December 2024)] | N = 1 |

| Libris—Swedish | (barn* OR “små barn*” OR “yngre barn*”) AND (inskolning* OR “aktivt föräldraskap” OR uppstart*) AND (førskolan OR dagis*) | N = 1 |

| Oria—University of Stavanger Library— English | Alle felt inneholder toddler* OR 0–3 OR “children under 3 years old” OR “children under 3” OR “young* child*” OG Alle felt inneholder ECEC* OR ECE* OR “ECEC center” OR “ECE center” OR “ECEC centre” OR “ECE centre” OR daycare OR “day care” OR “daycare center” OR “daycare centre” OR “day care center” OR “day care centre” OR childcare* OR “child care*” OR “childcare center*” OR “child care center*” OR “childcare centre*” OR “child care centre*” OR “centerbased care” OR “centrebased care” OR “centerbased childcare” OR “centrebased childcare” OR “centerbased child care” OR “centrebased child care” OR “center-based childcare” OR “centre-based childcare” OR “center-based child care” OR “centre-based child care” OR preschool* OR pre-school* OR kindergarten* OR “early childhood education” OR “early childhood education and care” OR crèche* OR creche* OR nurser* OR “day nurser*” OR “nursery school*” OR “infant school*” OR playschool* OR “play school*” OR “pre-primary school*” OG Alle felt inneholder transition* OR “transition period” OR “transition phase” OR starting* OR “starting period” OR “starting phase” OMFANG: Standard/Biblioteket på UIS Vis kun: Fra fagfellevurderte tidsskrift; Utgivelsesår/Opprettelsesdato: 2013–2024 | N = 819 |

| PsycInfo (OVID) | ((toddler* or 0–3 or “children under 3 years old” or “children under 3” or “young* child*”) and (ECEC* or ECE* or “ECEC center” or “ECE center” or “ECEC centre” or “ECE centre” or daycare or “day care” or “daycare center” or “daycare centre” or “day care center” or “day care centre” or childcare* or “child care*” or “childcare center*” or “child care center*” or “childcare centre*” or “child care centre*” or “centerbased care” or “centrebased care” or “centerbased childcare” or “centrebased childcare” or “centerbased child care” or “centrebased child care” or “center-based childcare” or “centre-based childcare” or “center-based child care” or “centre-based child care” or preschool* or pre-school* or kindergarten* or “early childhood education” or “early childhood education AND care” or cr#che* or creche* or nurser* or “day nurser*” or “nursery school*” or “infant school*” or playschool* or “play school*” or “pre-primary school*”) and (transition* or “transition period” or “transition phase” or starting* or “starting period” or “starting phase”)).mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] limit 1 to (peer reviewed journal and yr = “2013–Current”) ((toddler* or 0–3 or “children under 3 years old” or “children under 3” or “young* child*”) and (ECEC* or ECE* or “ECEC center” or “ECE center” or “ECEC centre” or “ECE centre” or daycare or “day care” or “daycare center” or “daycare centre” or “day care center” or “day care centre” or childcare* or “child care*” or “childcare center*” or “child care center*” or “childcare centre*” or “child care centre*” or “centerbased care” or “centrebased care” or “centerbased childcare” or “centrebased childcare” or “centerbased child care” or “centrebased child care” or “center-based childcare” or “centre-based childcare” or “center-based child care” or “centre-based child care” or preschool* or pre-school* or kindergarten* or “early childhood education” or “early childhood education and care” or cr#che* or creche* or nurser* or “day nurser*” or “nursery school*” or “infant school*” or playschool* or “play school*” or “pre-primary school*”) and (transition* or “transition period” or “transition phase” or starting* or “starting period” or “starting phase”)).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] limit 3 to (peer reviewed journal and yr =“2013–Current”) | N = 329 |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (toddler* OR 0–3 OR ”children under 3 years old” OR ”children under 3” OR ”young* child*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (ecec* OR ece* OR ”ECEC center” OR ”ECE center” OR ”ECEC centre” OR ”ECE centre” OR daycare OR ”day care” OR ”daycare center” OR ”daycare centre” OR ”day care center” OR ”day care centre” OR childcare* OR ”child care*” OR ”childcare center*” OR ”child care center*” OR ”childcare centre*” OR ”child care centre*” OR ”centerbased care” OR ”centrebased care” OR ”centerbased childcare” OR ”centrebased childcare” OR ”centerbased child care” OR ”centrebased child care” OR ”center-based childcare” OR ”centre-based childcare” OR ”center-based child care” OR ”centre-based child care” OR preschool* OR pre-school* OR kindergarten* OR ”early childhood education” OR ”early childhood education AND care” OR cr#che* OR creche* OR nurser* OR ”day nurser*” OR ”nursery school*” OR ”infant school*” OR playschool* OR ”play school*” OR ”pre-primary school*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (transition* OR ”transition period” OR ”transition phase” OR starting* OR ”starting period” OR ”starting phase”)) AND PUBYEAR > 2012 | N = 1159 |

| Web of Science | toddler* OR 0–3 OR “children under 3 years old” OR “children under 3” OR “young* child*” (All Fields) and ECEC* OR ECE* OR “ECEC center” OR “ECE center” OR “ECEC centre” OR “ECE centre” OR daycare OR “day care” OR “daycare center” OR “daycare centre” OR “day care center” OR “day care centre” OR childcare* OR “child care*” OR “childcare center*” OR “child care center*” OR “childcare centre*” OR “child care centre*” OR “centerbased care” OR “centrebased care” OR “centerbased childcare” OR “centrebased childcare” OR “centerbased child care” OR “centrebased child care” OR “center-based childcare” OR “centre-based childcare” OR “center-based child care” OR “centre-based child care” OR preschool* OR pre-school* OR kindergarten* OR “early childhood education” OR “early childhood education and care” OR crèche* OR creche* OR nurser* OR “day nurser*” OR “nursery school*” OR “infant school*” OR playschool* OR “play school*” OR “pre-primary school*” (All Fields) and transition* OR “transition period” OR “transition phase” OR starting* OR “starting period” OR “starting phase” (All Fields) | N = 776 |

Appendix B. Overview of the Included Studies

| Author(s) | Year of Publication | Title | Country | Study Purpose | Research Method | Study Design | Data Collection Method(s) | Sample Characteristics | Informants | Concept | Results | Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahnert, L. et al. | 2023 | Stress during transition from home to public childcare | Austria | Explore relationships | Quantitative | Longitudinal | Multimethod: saliva/cortisol samples, questionnaires, observations | 10–35 months (N = 104 children) | Professional caregivers, mothers, children | Stress and how stress levels were influenced by various factors, including mother–child and staff–child attachment, maternal worries, childcare environment characteristics (engagement, work experience), child and family demographics | The study examined cortisol rhythms in young children transitioning from home to public childcare, tracking stress levels over time and key influencing factors. Four cortisol profiles emerged: three showed regular diurnal patterns, while the fourth, the stress profile, displayed consistently low cortisol levels, indicating high stress. This profile was most common at the start of childcare, especially in younger children and those with prolonged maternal accompaniment.Most children (57.4%) maintained regular cortisol patterns over four months, while 15.9% showed the stress profile at least once, and 7.9% experienced persistent stress. Stress peaked early and declined over time, stabilizing into regular patterns. Secure attachment with mothers and caregivers helped ease the transition, reducing stress and supporting healthy cortisol regulation. | Parents and caregivers should intervene if a child is not thriving after two months in childcare. Small groups and large age differences can ease adjustment, while larger groups and smaller age gaps later promote social inclusion and reduce stress. Strong adult–child relationships at home and in childcare support smoother transitions. Future research should involve more national and international collaboration on children’s stress during this period. Persistent maternal anxiety can prolong stress in children, highlighting the importance of supporting parents to aid their child’s adjustment. |

| Albers, E. M. et al. | 2016 | Cortisol levels of infants in center care across the first year of life: Links with quality of care and infant temperament | Netherlands | Explore relationships | Quantitative | Longitudinal | Multimethod: saliva/cortisol samples, questionnaires, observations | 3–12 months (N = 64 children) | Professional caregivers, mothers, children | Stress and how stress levels were influenced by child temperament, quality of maternal behavior, and childcare process quality | Cortisol levels were consistently higher on childcare days than at home, indicating a stress response in infants. Levels peaked sharply in the first month and gradually declined but remained elevated, suggesting persistent stress. Morning cortisol stayed higher than afternoon levels, reflecting a normal rhythm. Stress responses varied based on temperament and maternal caregiving quality, with infants of more sensitive mothers or those with difficult temperaments showing higher cortisol. | Childcare centers should adopt individualized approaches, considering infants’ prior caregiving experiences and temperament. Future research should include larger samples, track children during similar activities, and follow them in the first months of childcare. Studies should also examine cortisol levels in low-SES children, collect more samples throughout the day, and assess behavior and social interactions at home and in childcare. Additionally, research should explore children’s developmental trajectories within childcare settings. |

| Bang, Y.-S. | 2014 | Teacher-caregivers’ perceptions of toddlers’ adaptation to a childcare center | Korea | Descriptive | Qualitative | View study | 1-on-1 interviews | N = 6 professional caregivers working with children under the age of 2 years | Professional caregivers | Children’s adaptation to the childcare center and the centers’ practice during the study period (from a professional caregiver perspective) | The study examined how teacher-caregivers perceived the transition to ECEC in Korea. In childcare centers, the teacher-caregivers used adaptation programs, and through 6 interviews, the article found that the teacher-caregivers used the programs differently. Some of the respondents emphasized the teacher-caregiver’s role more than the program did, while others found the program to be effective. | The study concludes that the teacher-caregivers’ role in transition periods should be sensitive to children’s needs. They should allow toddlers to explore the new setting and be patient with children. Teacher-caregivers should learn how to read children’s needs and respond sensitively to them. To ensure that the transition is a smooth process, parents play a key role, and teacher-caregivers should actively involve them. |

| Bernard, K. et al. | 2015 | Examining change in cortisol patterns during the 10-week transition to a new child-care setting | United States | Explore relationships | Quantitative | Longitudinal | Multimethod: saliva/cortisol samples, questionnaires | Children ranged in age from 1.2 months to 8 years old (M = 3.27 years, SD = 2.09). There were 42 infants between 0 and 18 months (25% of sample) and 34 toddlers between 18 and 36 months | Parents, children | Stress and how stress levels were influenced by developmental and environmental factors | The study tracks cortisol patterns in children over 10 weeks of transitioning to childcare, showing a significant rise from midmorning to afternoon due to a decline in midmorning levels, while afternoon levels stayed stable. Cortisol patterns at home and in childcare remained different—at home, levels declined as expected, but in childcare, they consistently rose from midmorning to afternoon. These findings suggest that the childcare environment continues to trigger a stress response even after weeks of attendance. | The persistence of rising cortisol from midmorning to afternoon over 10 weeks suggests that childcare remains challenging for children. While midmorning cortisol declines indicate gradual adaptation, elevated afternoon levels suggest ongoing stress from factors such as peer interactions. More longitudinal research is needed to track cortisol patterns beyond 10 weeks and their impact on development. The study emphasizes examining individual differences, such as temperament and social behavior, to identify vulnerable children. Future research should also explore the links between cortisol and specific childcare experiences, such as solitary play and peer conflicts. |

| Drugli, M. B. et al. | 2023 | Do toddlers’ levels of cortisol and the perceptions of parents and professional caregivers tell the same story about transition from home to childcare? A mixed method study | Norway | Explore relationships | Mixed method | Longitudinal | Multimethod: saliva/cortisol samples, informants’ notes | Toddlers (M age = 14.6 months, SD = 2.49) (N = 113 children) | Professional caregivers, parents, children | Changes in toddlers’ cortisol levels during the transition period (first month in childcare and 3-month follow-up) and parents’ and professional caregivers’ perceptions of toddlers’ settling in during this transition period | Cortisol levels rose significantly during the first two weeks of separation from parents, peaking in the second week before gradually decreasing and stabilizing by three months—returning to levels seen on the second day of childcare. Parent and caregiver notes confirmed these findings. Initially, with parents present, toddlers explored freely or stayed close to them, while key workers fostered a “caring triangle” with families. Many toddlers had visited childcare before starting, making the environment familiar. Parents noticed increased emotional reactivity and fatigue at home, while caregivers observed early separation challenges but noted positive relationships forming by week three. By three months, most toddlers were well adjusted and engaged in childcare. | The results highlight the importance of transition routines, such as pre-entry visits to childcare. Strong collaboration between caregivers and parents is essential to build a “caring triangle". Children need emotional support both at home and in childcare, including quiet activities at the end of the day and close caregiver interactions. Shorter childcare hours are recommended, and children struggling with the transition should receive early, skilled support. Future research should use observations and interviews to better understand how parents and caregivers can best support children during this period. |

| Ereky-Stevens, K. et al. | 2018 | Relationship building between toddlers and new caregivers in out-of-home childcare: Attachment security and caregiver sensitivity | Austria | Explore relationships | Quantitative | Longitudinal | Multimethod: observations (different tools and situations) | 10–33 months (N = 104 children) | Professional caregivers, children | The attachment relationship between the child and professional caregivers and how this attachment was influenced by dyadic caregiver sensitivity, 1-on-1 interactions, and interactions with all children in the group | Girls and children with caregivers who scored higher on group sensitivity showed higher attachment security. Toddlers’ attachment security was not predicted by dyadic sensitivity. | The findings support the development of attachment/relationship theory in childcare that includes children’s experiences in groups and not just 1-on-1 interactions. Measures that capture the quality of group interactions should be developed. Group dynamics and sensitivity are highly relevant to children’s experiences in childcare, which has important implications for practice, as the time for individual 1-on-1 interactions is limited. |

| Klette, T., and Killén, K. | 2019 | Painful transitions: A study of 1-year-old toddlers’ reactions to separation and reunion with their mothers after 1 month in childcare | Norway | Descriptive | Qualitative | Observation study | Observations | 13–15 months (N = 12 children) | Professional caregivers, mothers, children | Reactions and behaviors of the child during separation and reunion | The findings show that all toddlers experienced separation anxiety at various stages during the observed transitions. The limited number of staff members available in the early mornings and late afternoons often made the transitions more difficult. | It is essential to address how separation anxiety in toddlers at daycare is managed. It appears to be important to implement longer and more flexible adaptation times, shorter days, and improved staffing, particularly during early mornings and late afternoons. To prevent feelings of despair and detachment among Norwegian children, it is necessary to reconsider the current approach to toddler care in childcare facilities. |

| Lam, M. S. | 2014 | Transition to early childhood education: Parents’ use of coping strategies in dealing with children’s adjustment difficulties in Hong Kong | China | Descriptive | Qualitative | Phenomenological study | Multimethod: 1–1 interviews, focus group interviews | N = 29 parents of 31 children 2–3 years of age | Parents | Parents’ strategies of coping with children’s adjustment difficulties | The study explores how parents deliver and say goodbye to their children in ECEC in Hong Kong. The results can be summarized as follows: Parents had different strategies for their goodbyes with their children. Some focused on smooth separations, while others attempted to find the reason for the child’s reluctance, while a third group chose a hard line, offering the child little support and thinking that this choice would help in the long run. | The study suggests that teachers should be more proactive in supporting parents in terms of separation strategies. Hence, goodbye situations can be smoother for all involved. Parents might benefit from mentalizing the situation ahead of time so that the situation does not overwhelm them in the moment. |

| Macagno, A., and Molina, P. | 2020 | The construction of child-caregiver relationship in childcare centre: Adaptation of parent attachment diary for professional caregivers | Italy | Method development | Quantitative | Longitudinal | Observations | 4–35 months (N = 222 children) and N = 87 professional caregivers | Professional caregivers, children | Verify the adaptation of the PCAD and children’s (attachment) behavior during three specific stressful situations | Children show a significant decrease in avoidant and resistant attachment behavior after 2 and 4 months in childcare. Children’s secure behavior does not increase over time, but non-distressed behavior increases. This finding may indicate that children feel more secure after some time. | There is a need for further investigations into how behavior changes in specific situations and settings. In addition, there is a need to validate the PCAD, comparing PCAD scores with those of other validated tools. |

| McDevitt S. E., and Recchia, S. L. | 2022 | How toddlers new to child care become members of a classroom community | United States | Descriptive | Qualitative | Longitudinal | Multimethod: observations, 1–1 interviews, questionnaires | 2–2.5 years (N = 3 children) | Professional caregivers, parents, children | Children’s daily experiences, behaviors, movements, and interactions in becoming members of a classroom community | The process of integration into childcare was highly personalized, with each child showing distinct emotional, social, and behavioral adaptations. Some toddlers felt distressed upon arrival, while others engaged independently, progressively gaining confidence in interacting with teachers, peers, and activities at their own speed. | The study reveals how toddlers find well-being and belonging in childcare by forming genuine relationships with teachers and peers and using their agency to feel at home. As more children enter childcare early, they build foundational relationships with nonfamilial adults and peers, often in culturally different settings. A responsive childcare environment helps them maintain their sense of self and integrate into a new community. Peer relationships offer emotional security and learning opportunities, while teacher–child relationships enhance well-being. The study underscores the importance of daily practices in supporting young children’s holistic development. |

| Mellenius, N. et al. | 2023 | “I try to think behind my child’s cry”: Preparation for separation experiences in the light of parental mentalization | Finland | Explore relationships | Qualitative | Phenomenographic study | Multimethod: 1-on-1 interviews, clinical interviews, qualitative questionnaire | 10–24 months (N = 21 children) and N = 21 parents | Parents | The ways in which parents experience, conceptualize, perceive (parental mentalization), and prepare for the transition of the child from home to ECEC | Preparing for the initial transition phase encourages adaptable and complex thinking in parents, often evoking a range of emotions in advance. During this potentially stressful period, PM indicators primarily reflected a manageable level of uncertainty and thoughtful reflection experienced by parents. This finding highlights key functions of PM, as it supports both self-awareness and flexibility, helping parents navigate their own reactions—as well as their toddler’s—while entering a new stage of life together. | The study suggests that ECEC teachers should be attentive to parents and the parent–child relationship, giving positive feedback to parents to strengthen their ability to mentalize their child. Doing so could enable parents to help their child during the transition phase. |

| Nystad, K. et al. | 2021 | Toddlers’ stress during transition to childcare | Norway | Explore relationships | Quantitative | Longitudinal | Multimethod: saliva/cortisol samples, questionnaires | 10–20 months (N = 119 children) | Professional caregivers, parents, children | Stress across time of day and phase and how stress levels were influenced by age, gender, the number of siblings, and group size in childcare | Children showed elevated afternoon cortisol levels throughout the transition (up to 4–6 weeks), peaking during the separation phase but dropping in the evenings. Cortisol patterns varied by age—children 14 months and older had a slight afternoon cortisol increase on day three but saw a decline between separation and follow-up. In contrast, younger children did not show this decrease and had higher evening cortisol levels throughout, suggesting that they may need more time to adapt to childcare. | The results suggest shorter days and more parental presence in childcare during the separation phase. Parents should provide comfort in the evenings, while caregivers must be attentive to signs of distress. Calm afternoons, familiarization with the environment, and peer play facilitation are recommended. Flexible parental leave should be an option during the transition. Future research should include larger samples, identify children with higher cortisol levels, and examine temperament, attachment style, childcare quality, home–childcare collaboration, primary contact approaches, and parental presence in childcare. |

| Picchio, M., and Mayer, S. | 2019 | Transitions in ECEC services: The experience of children from migrant families | Italy | Descriptive | Qualitative | Ethnographic study | Multimethod: observations, informants’ notes | 18–36 months/19–34 months (2 different ages mentioned in the article; N = 26) and 36–48 months (N = 27) | Professional caregivers, mothers, children | Children from migrant families coping with the transition (challenges, competences (adaptation strategies) and supportive practices) | The study revealed the challenges faced by children from migrant families as they transitioned from home to ECEC services. It also identified the skills that they employed to navigate this new environment. Additionally, the analysis underscored how their experiences evolved throughout the year and highlighted the practices that promoted their well-being, engagement in activities, and interactions with both peers and adults. | The results offer valuable recommendations for enhancing practices in ECEC settings marked by significant diversity. The study emphasizes that ECEC practitioners encounter new challenges and questions in their daily routines. For instance, what strategies can assist children from migrant families in integrating into ECEC services? How is cultural and linguistic diversity accommodated within these services? What implicit and explicit messages do these children receive about their backgrounds and the knowledge that they bring? Addressing these questions is essential for developing an inclusive educational approach that respects diversity and helps children build a positive self-image. |

| Revilla, Y. L., Raittila, R. et al. | 2024a | Newcomer object ownership negotiations when transitioning from home care to early childhood education and care in Finland | Finland | Explore relationships | Qualitative | Longitudinal case study | Multimethod: observations (different tools and methods), field notes | 10–18 months (N = 3 children) | Professional caregivers, children | How the institutional space of ECEC is (re)produced within newcomers’ encounters with others during the transition from home to ECEC by studying the negotiations of object ownership in newcomers’ encounters with peers, as mediated by teachers | The findings reveal that newcomers played an active role in shaping the ECEC environment by developing their own interpretations of objects and ownership and by practicing their unique ways of interacting with these objects. Additionally, the results highlight that teachers significantly impacted the outcomes of these interactions, thus influencing the collective understanding of objects and ownership within the ECEC setting. | This research enhances our relational understanding of young children’s interactions, transitions, and the ECEC environment, focusing on how space is (re)produced through negotiations. It emphasizes the importance for practitioners to consider and trust children’s perceptions of ‘what is happening’ to teach and promote fairness and to advance practices that support children’s agency. Although accessing and comprehending children’s perspectives can be challenging, the study suggests that their views are valid and reliable and should be acknowledged accordingly. |

| Revilla, Y. L., Rutanen, N. et al. | 2024b | Children under two as co-constructors of their transition from home care to early childhood education and care | Finland | Explore relationships | Qualitative | Longitudinal case study | Multimethod: observations (different tools and methods), field notes | 9–18 months (N = 4 children) | Professional caregivers, parents, children | The ways children contribute to the co-construction of their own transition from home to ECEC and how these contributions were constructed by space | The study results indicate that from their very first day, children actively shaped their arrival experiences by taking advantage of and creating opportunities to engage with the ECEC environment. Over time, they established their own arrival routines and became more familiar with the space and its potential, enhancing their creativity and resourcefulness in finding and creating opportunities, such as initiating interactions with peers. | Aligning with contemporary research in childhood studies, this study suggests that observing children’s practices as a form of participation is crucial. Further research should explore children’s prior experiences before starting ECEC, for example, by gathering data from their visits to the center before their first transition day and/or from their homes. Additionally, extending the study by collecting daily data over a longer period would be beneficial. Research on older children’s practices during their transition from home care to ECEC could also provide valuable insights into how they co-construct their transitions, highlighting the influence of age and maturity. |

| Rintakorpi, K. et al. | 2014 | Documenting with parents and toddlers: A Finnish case study | Finland | Method development | Qualitative | Longitudinal case study | Multimethod: photos, informants’ notes, ethnographical notes, observations, videotaped discussions, e-mail interview | 18 months (N = 1 child) | Professional caregivers, parents, children | Effectiveness (content and process) of a pedagogical documentation tool called “the Fan” in understanding a child during the transition | Pedagogical documentation using the Fan not only served as a tool for recording facts but also carried institutional significance. It facilitated the exchange of information about a child’s life between home and kindergarten, making the child’s interests and emotions more visible. This study follows one child during his first weeks in ECEC and studies how a pedagogical tool with pictures of the child’s home environment can function to ease the transition. | The study shows how pedagogical practices can be used to smooth the transition for toddlers. |

| Schärer, J. H. | 2018 | How educators define their role: Building “professional” relationships with children and parents during transition to childcare: A case study | Canada | Descriptive | Qualitative | Case study | Multimethod: 1-on-1 interviews, videotaped discussions | N = 4 professional caregivers in an infant/toddler center with 12 children | Professional caregivers | Role of professional caregivers (attitudes and experience) and building relationships with children and parents during the transition | Educators are concerned about their professional roles, which can influence the center’s structure, schedules, and relationships with children and parents. They worry that close attachments to children are unhealthy and could lead to children becoming overly dependent on a specific educator. | The findings serve as a foundation for discussing how educators can maintain professionalism while adopting a pedagogical approach that prioritizes relationships. |

| Swartz, M. I., and Easterbrooks, M. A. | 2014 | The role of parent, provider, and child characteristics in parent-provider relationships in infant and toddler classrooms | United States | Explore relationships | Quantitative | Cross-sectional study | Questionnaires | N = 192 parents with children 3–39 months old, N = 95 professional caregivers of infant/toddler classrooms | Professional caregivers, parents | The parent–professional caregiver relationship and how it might be influenced by parents’ and professionals’ backgrounds, child characteristics, parent separation anxiety, provider knowledge of child development, and provider job satisfaction | Parents viewed their relationships with providers more positively when they had prior experience working together and felt less anxious about childcare. In contrast, providers with past experience working with parents viewed relationships less favorably when parents were more anxious, although this was not the case in newer relationships. Providers with no prior experience with parents had more positive views when they possessed greater knowledge of child development. Those with more child development knowledge also reported more frequent communication with parents, particularly those with children who had easier temperaments. | This study enhances the understanding of the factors that support strong family partnerships and, in turn, high-quality early childhood education. It also highlights the challenge of balancing professionalism with meeting both individual and group needs. |

| Søe, M. A. et al. | 2023 | Transition to preschool: Paving the way for preschool teacher and family relationship-building | Sweden | Explore relationships | Mixed method | Comparative study | Multimethod: quantitative and qualitative questionnaires | N = 535 professional caregivers (most children in Sweden enter childcare before the age of 2 years, which is part of the national regulation in Sweden) | Professional caregivers | The organization of the transition process and how different introduction models might influence family–teacher relationship-building and child adjustment | The study examines different approaches to transition to ECEC practices in Sweden. It combines qualitative (interviews of preschool teachers) with quantitative (a survey of preschool teachers) methods. Through these approaches, the study reveals that there are various approaches, although it argues that approaches that involve parents have the benefit of developing valuable relationships between teachers and parents. | Approaches that involve parents develop important relationships with teachers, which are important for children’s well-being in the transition period and for long-term cooperation between the institution and home. |

| Tebet, G. G. C. et al. | 2020 | Babies’ transition between family and early childhood education and care: A mosaic of discourses about quality of services | Brazil | Descriptive | Qualitative | Mosaic approach | Multimethod: documents, joint interviews, observations, photos, ethnographical notes, cartographic productions | Babies (age not specified) | Professional caregivers, parents, children | Childcare quality and infants’ and toddlers’ transition to childcare | The findings illustrate how various factors, such as laws, normative documents, family expectations, educational planning and routines, available toys, space, babies, families, and professionals come together to form a complex mosaic of perspectives on what defines quality in early childhood education during babies’ initial days in daycare centers. | To define quality in early childhood education and care services, it is crucial to develop a framework that emphasizes a pedagogy that is capable of challenging and transforming gender and race stereotypes. This approach should also align with the principles outlined in Brazilian documents and laws. |

References

- Ahnert, L., Eckstein-Madry, T., Datler, W., Deichmann, F., & Piskernik, B. (2023). Stress during transition from home to public childcare. Applied Developmental Science, 27(4), 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, E. M., Beijers, R., Riksen-Walraven, J. M., Sweep, F. C., & De Weerth, C. (2016). Cortisol levels of infants in center care across the first year of life: Links with quality of care and infant temperament. Stress, 19(1), 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, Y.-S. (2014). Teacher-caregivers’ perceptions of toddlers’ adaptation to a childcare center. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(8), 1279–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, K., Peloso, E., Laurenceau, J. P., Zhang, Z., & Dozier, M. (2015). Examining change in cortisol patterns during the 10-week transition to a new child-care setting. Child Development, 86(2), 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blakemore, S.-J., & Frith, U. (2005). The learning brain: Lessons for education. Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Brooker, L. (2008). Supporting transitions in the early years: Supporting early learning. Open University Press; McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. (2019). Council recommendation on high-quality early childhood education and care systems (Official Journal of the European Union No. C 189/4). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019H0605(01) (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Dalli, C., & White, E. J. (2017). Policy and pedagogy for birth-to-three-year-olds. In E. J. White, & C. Dalli (Eds.), Under three-year-olds in policy and practice (pp. 1–14). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drugli, M. B., Nystad, K., Lydersen, S., & Brenne, A. S. (2023). Do toddlers’ levels of cortisol and the perceptions of parents and professional caregivers tell the same story about transition from home to childcare? A mixed method study. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1165788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ereky-Stevens, K., Funder, A., Katschnig, T., Malmberg, L. E., & Datler, W. (2018). Relationship building between toddlers and new caregivers in out-of-home childcare: Attachment security and caregiver sensitivity. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 42(1), 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission/European Education and Culture Executive Agency/Eurydice. (2019). Key data on early childhood education and care in Europe—2019 edition. Eurydice report. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/s/oa8x (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Fleer, M., & Linke, P. (2016). Connecting with babies: Responding appropriately to infants (3rd ed.). Early Childhood Australia Inc. [Google Scholar]

- French, G. (2019). Tuning into babies: Nurturing relationships in early childhood. In B. Mooney (Ed.), Irelands’s yearbook of education 2018–2019 (pp. 105–109). Education Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Furuya-Kanamori, L., Lin, L., Kostoulas, P., Clark, J., & Xu, C. (2023). Limits in the search date for rapid reviews of diagnostic test accuracy studies. Research Synthesis Methods, 14(2), 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamst, K. M. T. (2017). Profesjonelle barnesamtaler. Å ta barnet på alvor [Professional conversations with children: Taking the child seriously] (2nd ed.). Universitetsforlaget. [Google Scholar]

- Gath, M. E., Herold, L., Hunkin, E., McNair, L. J., Redder, B., Rutanen, N., & White, E. J. (2024). Infants’ emotional and social experiences during and after the transition to early childhood education and care. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 22(1), 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldbrandsen, A., Furenes Klippen, M. I., & Munthe, E. (2023). Forskningskartlegging og vurdering. Empirisk barnehageforskning for de skandinaviske landene i 2020 [Review of research and assessment. Empirical research on scandinavian early childhood education and care in 2020]. Kunnskapssenter for Utdanning, Universitetet i Stavanger. Available online: https://www.uis.no/sites/default/files/2023-01/13767300%20Rapport%20NB-ECEC%20NOR%20PDF%20UU.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Guldbrandsen, A., Kalvatn Friestad, N., & Furenes Klippen, M. I. (2024). Empirisk barnehageforskning for de skandinaviske landene i 2021. Forskningskartlegging og vurdering [Empirical research on scandinavian early childhood education and care in 2021. Review of research and assessment]. Kunnskapssenter for Utdanning, Universitetet i Stavanger. Available online: https://www.uis.no/sites/default/files/2024-02/Empirisk%20barnehageforskning%20for%20de%20skandinaviske%20landene%20i%202021.%20Forskningskartlegging%20og%20vurdering.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Guldbrandsen, A., Ree, M., Kalvatn Friestad, N., Velde Helgøy, K., Furenes Klippen, M. I., Thijssen, M. W. P., Forsström, S. E., & Bjergsten Njå, M. (2025). Empirical research on Scandinavian early childhood education and care in 2022 and 2023. Review of research and assessment. Knowledge Centre for Education, University of Stavanger. Available online: https://www.uis.no/sites/default/files/2025-02/KSU%20rapport%20ENG%202022-2023.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Hartle, L., Lorio, C. M., & Kosharek, C. (2023). Establishing innovative partnerships to support transitions from early intervention to preschool in the United States of America: Lessons from parent and provider experiences. Education 3–13—International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education, 51(4), 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, L. K. M., Elwick, S., Redder, B., Westbrook, F., & Hawkes, K. (2022). The “things” of first transitions. In E. J. White, H. Marwick, N. Rutanen, K. S. Amorim, & L. K. M. Herold (Eds.), First transitions to early childhood education and care. Intercultural dialogues across the globe (Vol. 5, pp. 255–278). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Klette, T., & Killén, K. (2019). Painful transitions: A study of 1-year-old toddlers’ reactions to separation and reunion with their mothers after 1 month in childcare. Early Child Development and Care, 189(12), 1970–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M. S. (2014). Transition to early childhood education: Parents’ use of coping strategies in dealing with children’s adjustment difficulties in Hong Kong. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 39(3), 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macagno, A., & Molina, P. (2020). The construction of child-caregiver relationship in childcare centre: Adaptation of parent attachment diary for professional caregivers. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 28(3), 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDevitt, S. E., & Recchia, S. L. (2022). How toddlers new to child care become members of a classroom community. Early Child Development and Care, 192(3), 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellenius, N., Korja, R., Kalland, M., Huttunen, R., Sourander, J., Salo, S., Westerlund-Cook, S., & Junttila, N. (2023). “I try to think behind my child’s cry”: Preparation for separation experiences in the light of parental mentalization. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 22(3), 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, H., & Hall, H. (2017). New mothers transitioning to employment: Impact on infant feeding practices. In L. Li, G. Quiñones, & A. Ridgway (Eds.), Studying babies and toddlers. Relationships in cultural contexts (pp. 63–80). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2007). A science-based framework for early childhood policy: Using evidence to improve outcomes in learning, behavior, and health for vulnerable children. Harvard University, Center on the Developing Child. Available online: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Policy_Framework.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2017). Framework plan for kindergartens. Available online: https://www.udir.no/contentassets/7c4387bb50314f33b828789ed767329e/framework-plan-for-kindergartens--rammeplan-engelsk-pdf.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Nystad, K., Drugli, M. B., Lydersen, S., Lekhal, R., & Buøen, E. S. (2021). Toddlers’ stress during transition to childcare. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 29(2), 157–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A. (2017). Understanding transitions in the early years: Supporting change through attachment and resilience (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2017). Starting strong V: Transitions from early childhood education and care to primary education. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2018). Starting strong. Engaging young children: Lessons from research about quality in early childhood education and care. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2019). Education at a glance 2019: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2021). PF3.2: Enrolment in childcare and pre-school. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/data/datasets/family-database/pf3_2_enrolment_childcare_preschool.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and Mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., & McKenzie, J. E. (2022). Introduction to PRISMA 2020 and implications for research synthesis methodologists. Research Synthesis Methods, 13(2), 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picchio, M., & Mayer, S. (2019). Transitions in ECEC services: The experience of children from migrant families. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 27(2), 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, Y. L., Raittila, R., Sevon, E., & Rutanen, N. (2024a). Newcomer object ownership negotiations when transitioning from home care to early childhood education and care in Finland. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 32(2), 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, Y. L., Rutanen, N., Sevón, E., & Raittila, R. (2024b). Children under two as co-constructors of their transition from home care to early childhood education and care. Barn: Forskning om Barn og Barndom i Norden, 42(1), 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rintakorpi, K., Lipponen, L., & Reunamo, J. (2014). Documenting with parents and toddlers: A Finnish case study. Early Years, 34(2), 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schärer, J. H. (2018). How educators define their role: Building ‘professional’ relationships with children and parents during transition to childcare: A case study. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 26(2), 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solberg, E., & Wendt, K. (2021). Det norske forsknings-og innovasjonssystemet–Statistikk og indikatorer 2021 [The norwegian research and innovation system—Statistics and indicators]. Norges Forskningsråd. Available online: https://www.forskningsradet.no/siteassets/publikasjoner/2021/indikatorrapporten-2021.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Søe, M. A., Schad, E., & Psouni, E. (2023). Transition to preschool: Paving the way for preschool teacher and family relationship-building. Child and Youth Care Forum, 52(6), 1249–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumsion, J., Harrison, L., Press, F., McLeod, S., Goodfellow, J., & Bradley, B. (2011). Researching infants’ experiences of early childhood education and care. In D. Harcourt, B. Perry, & T. Waller (Eds.), Researching young children’s perspectives: Debating the ethics and dilemmas of educational research with children (pp. 113–127). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, M. I., & Easterbrooks, M. A. (2014). The role of parent, provider, and child characteristics in parent–provider relationships in infant and toddler classrooms. Early Education and Development, 25(4), 573–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebet, G. G. D. C., Lopes dos Santos, N., Costa, J., Santos, B. L., Pontes, L. C. B., de Oliveira, S., & Ângela D’Andrea, M. (2020). Babies’ transition between family and early childhood education and care: A mosaic of discourses about quality of services. Early Years, 40(4–5), 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Schaik, S. D. M., Leseman, P. P. M., & Huijbregts, S. K. (2014). Cultural diversity in teachers’ group-centered beliefs and practices in early childcare. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(3), 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E. J., Marwick, H., Rutanen, N., Amorim, K. S., & Herold, L. K. M. (Eds.). (2022a). First transitions to early childhood education and care. Intercultural dialogues across the globe (Vol. 5). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- White, E. J., McNair, L., Redder, B., Meireles Santos da Costa, N., Amorim, K. S., Harju, K., Westbrook, F., Herold, L. K. M., Revilla, Y. L., & Marwick, H. (2022b). Enacted pedagogies in first transitions. In E. J. White, H. Marwick, N. Rutanen, K. S. Amorim, & L. K. M. Herold (Eds.), First transitions to early childhood education and care. Intercultural dialogues across the globe (Vol. 5, pp. 109–135). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- White, E. J., Rutanen, N., Marwick, H., Souza Amorim, K., Karagiannidou, E., & Herold, L. K. M. (2020). Expectations and emotions concerning infant transitions to ECEC: International dialogues with parents and teachers. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 28(3), 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PCC (Population, Concept, Context) | Search String— English | Search String— Danish | Search String— Norwegian | Search String— Swedish |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Children under 3 years | toddler* OR 0–3 OR “children under 3 years old” OR “children under 3” OR “young* child*” | børn* OR småbørn OR vuggestuebørn OR “1–3 år” | småbarn OR “små barn” OR “1–3 åring*” OR “ettåring*” OR “ett-til-treåring*”OR “de yngste barna” OR “de minste barna” | barn* OR “små barn*” OR “yngre barn*” |

| Transition | transition* OR “transition period” OR “transition phase” OR starting* OR “starting period” OR “starting phase | overgang* OR modtakelse OR indkjøring | “foreldreaktiv tilvenning” OR “start i barnehagen” OR tilvenning OR innkjøring OR oppstart OR overgang OR “sammenheng mellom hjem og barnehage” | inskolning* OR “aktivt föräldraskap” OR uppstart* |

| ECEC | ECEC* OR ECE* OR “ECEC center” OR “ECE center” OR “ECEC centre” OR “ECE centre” OR daycare OR “day care” OR “daycare center” OR “daycare centre” OR “day care center” OR “day care centre” OR childcare* OR “child care*” OR “childcare center*” OR “child care center*” OR “childcare centre*” OR “child care centre*” OR “centerbased care” OR “centrebased care” OR “centerbased childcare” OR “centrebased childcare” OR “centerbased child care” OR “centrebased child care” OR “center-based childcare” OR “centre-based childcare” OR “center-based child care” OR “centre-based child care” OR preschool* OR pre-school* OR kindergarten* OR “early childhood education” OR “early childhood education and care” OR crèche* OR creche* OR nurser* OR “day nurser*” OR “nursery school*” OR “infant school*” OR playschool* OR “play school*” OR “pre-primary school*” | børnehave* OR vuggestue* OR dagpleje* | barnehage OR småbarnsavdeling OR småbarnsgruppe | førskolan OR dagis* |

| Source | Date | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| Academic Search Premier | 19 August 2024 | 319 |

| ERIC | 19 August 2024 | 359 |

| Idunn—Danish | 19 August 2024 | 10 |

| Idunn—Norwegian | 19 August 2024 | 36 |

| Idunn—Swedish | 19 August 2024 | 1 |

| Libris—Swedish | 19 August 2024 | 1 |

| Oria | 19 August 2024 | 819 |

| PsycInfo | 19 August 2024 | 329 |

| Scopus | 19 August 2024 | 1159 |

| Web of Science | 19 August 2024 | 776 |

| Total | 3809 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Trijp, C.P.J.; Ree, M.; Belland, T.E.; Esmaeeli, S.; Eidsvåg, G.M.; Asikanius, M.A.; Rosell, L.Y. A Systematic Scoping Review on the Transition of Under-3-Year-Old Children from Home to Early Childhood Education and Care. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050589

van Trijp CPJ, Ree M, Belland TE, Esmaeeli S, Eidsvåg GM, Asikanius MA, Rosell LY. A Systematic Scoping Review on the Transition of Under-3-Year-Old Children from Home to Early Childhood Education and Care. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):589. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050589

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Trijp, Catharina Petronella Johanna, Marianne Ree, Tove Erna Belland, Sara Esmaeeli, Gunnar Magnus Eidsvåg, Mariella Annika Asikanius, and Lars Yngve Rosell. 2025. "A Systematic Scoping Review on the Transition of Under-3-Year-Old Children from Home to Early Childhood Education and Care" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050589

APA Stylevan Trijp, C. P. J., Ree, M., Belland, T. E., Esmaeeli, S., Eidsvåg, G. M., Asikanius, M. A., & Rosell, L. Y. (2025). A Systematic Scoping Review on the Transition of Under-3-Year-Old Children from Home to Early Childhood Education and Care. Education Sciences, 15(5), 589. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050589